Homophobia

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who identify or are perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual.[2][3][4] It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred, or antipathy, may be based on irrational fear and may sometimes be attributed to religious beliefs.[5][6] Homophobia is observable in critical and hostile behavior such as discrimination and violence on the basis of sexual orientations that are non-heterosexual.[2][3][7]

Recognized types of homophobia include institutionalized homophobia, e.g. religious homophobia and state-sponsored homophobia, and internalized homophobia, experienced by people who have same-sex attractions, regardless of how they identify.[8][9] According to 2010 Hate Crimes Statistics released by the FBI National Press Office, 19.3 percent of hate crimes across the United States "were motivated by a sexual orientation bias."[10] Moreover, in a Southern Poverty Law Center 2010 Intelligence Report extrapolating data from FBI national hate crime statistics from 1995 to 2008, found that LGBT people were "far more likely than any other minority group in the United States to be victimized by violent hate crime."[11]

Etymology

Although sexual attitudes tracing back to Ancient Greece – from the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity (c. 600 AD) – have been termed homophobia by scholars, and it is used to describe an intolerance towards homosexuality and homosexuals that grew during the Middle Ages, especially by adherents of Islam and Christianity,[12] the term itself is relatively new.[13]

Coined by George Weinberg, a psychologist, in the 1960s,[14] the term homophobia is a blend of (1) the word homosexual, itself a mix of neo-classical morphemes, and (2) phobia from the Greek φόβος, phóbos, meaning "fear", "morbid fear" or "aversion".[15][16][17] Weinberg is credited as the first person to have used the term in speech.[13] The word homophobia first appeared in print in an article written for the 23 May 1969 edition of the American pornographic magazine Screw, in which the word was used to refer to heterosexual men's fear that others might think they are gay.[13]

Conceptualizing anti-LGBT prejudice as a social problem worthy of scholarly attention was not new. A 1969 article in Time described examples of negative attitudes toward homosexuality as "homophobia", including "a mixture of revulsion and apprehension" which some called homosexual panic.[18] In 1971, Kenneth Smith used homophobia as a personality profile to describe the psychological aversion to homosexuality.[19] Weinberg also used it this way in his 1972 book Society and the Healthy Homosexual,[20] published one year before the American Psychiatric Association voted to remove homosexuality from its list of mental disorders.[21][22] Weinberg's term became an important tool for gay and lesbian activists, advocates, and their allies.[13] He describes the concept as a medical phobia:[20]

[A] phobia about homosexuals.... It was a fear of homosexuals which seemed to be associated with a fear of contagion, a fear of reducing the things one fought for — home and family. It was a religious fear and it had led to great brutality as fear always does.[13]

In 1981, homophobia was used for the first time in The Times (of London) to report that the General Synod of the Church of England voted to refuse to condemn homosexuality.[23]

However, when taken literally, homophobia may be a problematic term. Professor David A. F. Haaga says that contemporary usage includes "a wide range of negative emotions, attitudes and behaviours toward homosexual people," which are characteristics that are not consistent with accepted definitions of phobias, that of "an intense, illogical, or abnormal fear of a specified thing."[24]

Types

Homophobia manifests in different forms, and a number of different types have been postulated, among which are internalized homophobia, social homophobia, emotional homophobia, rationalized homophobia, and others.[25] There were also ideas to classify homophobia and other types of bigotry as intolerant personality disorder.[26]

In 1992, the American Psychiatric Association, recognizing the power of the stigma against homosexuality, issued the following statement, reaffirmed by the Board of Trustees, July 2011:[27]

Whereas homosexuality per se implies no impairment in judgment, stability, reliability, or general social or vocational capabilities, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) calls on all international health organizations, psychiatric organizations, and individual psychiatrists in other countries to urge the repeal in their own countries of legislation that penalizes homosexual acts by consenting adults in private. Further, APA calls on these organizations and individuals to do all that is possible to decrease the stigma related to homosexuality wherever and whenever it may occur.

Institutional

Religious attitudes

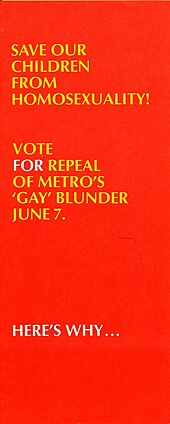

Some world religions contain anti-homosexual teachings, while other religions have varying degrees of ambivalence, neutrality, or incorporate teachings that regard homosexuals as third gender. Even within some religions which generally discourage homosexuality, there may also be people who view homosexuality positively, and some religious denominations bless or conduct same-sex marriages. There also exist so-called Queer religions, dedicated to serving the spiritual needs of LGBTQI persons. Queer theology seeks to provide a counterpoint to religious homophobia.[28] In 2015, attorney and author Roberta Kaplan stated that Kim Davis "is the clearest example of someone who wants to use a religious liberty argument to discriminate [against same-sex couples]."[29]

Christianity and the Bible

Passages commonly interpreted as condemning homosexuality or same-gender sexual relations are found in both Old and New Testaments of the Bible. Leviticus 18:22 says "Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination." The destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah is also commonly seen as a condemnation of homosexuality. Christians and Jews who oppose homosexuality may often cite such passages; the historical context and interpretation of which is more complicated. Scholarly debate over the interpretation of these passages has tended to focus on placing them in proper historical context, for instance pointing out that Sodom's sins are historically interpreted as being other than homosexuality,[30] and on the translation of rare or unusual words in the passages in question. In Religion Dispatches magazine, Candace Chellew-Hodge argues that the six or so verses that are often cited to condemn LGBT people are referring instead to "abusive sex". She states that the Bible has no condemnation for "loving, committed, gay and lesbian relationships" and that Jesus was silent on the subject.[31] This view is opposed by a number of conservative evangelicals,[32] including Robert A. J. Gagnon.[33]

The official teaching of the Catholic Church regarding homosexuality is that same-sex behavior should not be expressed.[34] In the United States, a February 2012 Pew Research Center poll shows that Catholics support gay marriage by a margin of 52% to 37%.[35] That is a shift upwards from 2010, when 46% of Catholics favored gay marriage.[36] The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that, "'homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered.'...They are contrary to the natural law.... Under no circumstances can they be approved."[34]

Islam and Sharia

In some cases, the distinction between religious homophobia and state-sponsored homophobia is not clear, a key example being territories under Islamic authority. All major Islamic sects forbid homosexuality, which is a crime under Sharia Law and treated as such in most Muslim countries. In Afghanistan, for instance, homosexuality carried the death penalty under the Taliban. After their fall, homosexuality was reduced from a capital crime to one that is punished with fines and prison sentences.[37][38][39][40] After the revolution of 1979 in Iran and the establishment of a new government based on Islamic Sharia, the pressure and punishment against LGBT people has expanded in this country.[41][42][43] The legal situation in the United Arab Emirates, however, is unclear.

In 2009, the International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA) published a report entitled State Sponsored Homophobia 2009,[44] which is based on research carried out by Daniel Ottosson at Södertörn University College, Stockholm, Sweden. This research found that of the 80 countries around the world that continue to consider homosexuality illegal:[45][46]

- Seven carry the death penalty for homosexual activity: Iran, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Yemen, Afghanistan and Brunei.[47][40] Since the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, the Iranian government has executed more than 4,000 people charged with homosexual acts.[48][49] In Saudi Arabia, the maximum punishment for homosexuality is public execution, but the government will use other punishments – e.g., fines, jail time, whipping – and even forced sex change as alternatives, unless it feels that people engaging in homosexual activity are challenging state authority by engaging in LGBT social movements.[50] On the other hand, due to the traditional and religious structure of Islamic societies, people also refuse to accept the identity of homosexuals and have a conservative attitude towards them.[51][52][53][54]

- Two do in some regions: Nigeria, Somalia[47]

In 2001, Al-Muhajiroun, an international organization seeking the establishment of a global Islamic caliphate, issued a fatwa declaring that all members of The Al-Fatiha Foundation (which advances the cause of gay, lesbian, and transgender Muslims) were murtadd, or apostates, and condemning them to death. Because of the threat and because they come from conservative societies, many members of the foundation's site still prefer to be anonymous so as to protect their identities while they are continuing a tradition of secrecy.[55]

In some regions, gay people have been persecuted and murdered by Islamist militias,[56] such as Al-Nusra Front and ISIL in parts of Iraq and Syria.[57]

State-sponsored

| Same-sex intercourse illegal. Penalties: | |

Prison; death not enforced | |

Death under militias | Prison, with arrests or detention |

Prison, not enforced1 | |

| Same-sex intercourse legal. Recognition of unions: | |

Extraterritorial marriage2 | |

Limited foreign | Optional certification |

None | Restrictions of expression, not enforced |

Restrictions of association with arrests or detention | |

1No imprisonment in the past three years or moratorium on law.

2Marriage not available locally. Some jurisdictions may perform other types of partnerships.

State-sponsored homophobia includes the criminalization and penalization of homosexuality, hate speech from government figures, and other forms of discrimination, violence, persecution of LGBT people.[58]

Past governments

In medieval Europe, homosexuality was considered sodomy and was punishable by death. Persecutions reached their height during the Medieval Inquisitions, when the sects of Cathars and Waldensians were accused of fornication and sodomy, alongside accusations of Satanism. In 1307, accusations of sodomy and homosexuality were major charges leveled during the Trial of the Knights Templar.[59] The theologian Thomas Aquinas was influential in linking condemnation of homosexuality with the idea of natural law, arguing that "special sins are against nature, as, for instance, those that run counter to the intercourse of male and female natural to animals, and so are peculiarly qualified as unnatural vices."[60]

Although bisexuality was accepted as normal human behavior in Ancient China,[61] homophobia became ingrained in the late Qing dynasty and the Republic of China due to interactions with the Christian West,[62] and homosexual behavior was outlawed in 1740.[63] During the Cultural Revolution, homosexuality was treated by the government as a "social disgrace or a form of mental illness", and individuals who were homosexual widely faced persecution. Although there were no laws specifically against homosexuality, other laws were used to prosecute homosexual people and they were "charged with hooliganism or disturbing public order."[64][better source needed]

The Soviet Union under Vladimir Lenin decriminalized homosexuality in 1922, long before many other European countries. The Soviet Communist Party effectively legalized no-fault divorce, abortion and homosexuality, when they abolished all the old Tsarist laws and the initial Soviet criminal code kept these liberal sexual policies in place.[65] Lenin's emancipation was reversed a decade later by Joseph Stalin and homosexuality remained illegal under Article 121 until the Yeltsin era.

In Nazi Germany, gay men were persecuted and approximately five to fifteen thousand were imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps.[66]

Current governments

Homosexuality is illegal in 74 countries.[67] The North Korean government condemns Western gay culture as a vice caused by the decadence of a capitalist society, and it denounces it as promoting consumerism, classism, and promiscuity.[68] In North Korea, "violating the rules of collective socialist life" can be punished with up to two years' imprisonment.[69] Park Jeong-Won, a law professor at Kookmin University, said that, while he was not aware of any North Korean laws explicitly prohibiting homosexual relationships, laws against extramarital affairs and breaking moral customs would likely be used to prosecute homosexual acts.[70]

Robert Mugabe, the former president of Zimbabwe, waged a violent campaign against LGBT people, arguing that before colonisation, Zimbabweans did not engage in homosexual acts.[71] His first major public condemnation of homosexuality was in August 1995, during the Zimbabwe International Book Fair.[72] He told an audience: "If you see people parading themselves as lesbians and gays, arrest them and hand them over to the police!"[73] In September 1995, Zimbabwe's parliament introduced legislation banning homosexual acts.[72] In 1997, a court found Canaan Banana, Mugabe's predecessor and the first President of Zimbabwe, guilty of 11 counts of sodomy and indecent assault.[74][75]

In Poland, local towns, cities,[76][77] and Voivodeship sejmiks[78] have declared their respective regions as LGBT ideology free zone with the encouragement of the ruling Law and Justice party.[76]

Since 2006, under Vladimir Putin, regions in Russia have enacted varying laws restricting the distribution of materials promoting LGBT relationships to minors. In June 2013, a federal law criminalizing the distribution of materials among minors in support of non-traditional sexual relationships was enacted as an amendment to an existing child protection law. The law resulted in the numerous arrests of Russian LGBT citizens.[79] In 2023 the Russian Supreme Court declared that the international LGBT rights movement is an extremist organization.[80]

Internalized

Internalized homophobia refers to negative stereotypes, beliefs, stigma, and prejudice about homosexuality and LGBTQ people that a person with same-sex attraction turns inward on themselves, whether or not they identify as LGBT.[13][81][8]

Some studies have shown that people who are homophobic are more likely to have repressed homosexual desires. In 1996, a controlled study of 64 heterosexual men (half said they were homophobic by experience, with self-reported orientation) at the University of Georgia found that men who were found to be homophobic (as measured by the Index of Homophobia) were considerably more likely to experience more erectile responses when exposed to homoerotic images than non-homophobic men.[82][83] Weinstein and colleagues[84] arrived at similar results when researchers found that students who came from controlling and homophobic homes were most likely to reveal repressed homosexual attraction. The researchers said that this explained why some religious leaders who denounce homosexuality are later revealed to have secret homosexual relations. One co-author said, "In many cases these are people who are at war with themselves and they are turning this internal conflict outward."[85] A 2016 eye-tracking study showed that heterosexual men with high negative impulse reactions toward homosexuals gazed for longer periods at homosexual imagery than other heterosexual men.[86] According to Cheval et al. (2016), these findings reinforce the necessity to consider that homophobia might reflect concerns about sexuality in general and not homosexuality in particular.[87] In contrast, Jesse Marczyk argued in Psychology Today that homophobia is not necessarily repressed homosexuality.[88]

The effect of these ideas depends on how much and which they have consciously and subconsciously internalized.[89] These negative beliefs can be mitigated with education, life experience, and therapy,[8][90] especially with gay-friendly psychotherapy/analysis.[91] Internalized homophobia also applies to conscious or unconscious behaviors which a person feels the need to promote or conform to cultural expectations of heteronormativity or heterosexism. This can include repression and denial coupled with forced outward displays of heteronormative behavior for the purpose of appearing or attempting to feel "normal" or "accepted". Other expressions of internalized homophobia can also be subtle. Some less overt behaviors may include making assumptions about the gender of a person's romantic partner, or about gender roles.[13] Some researchers also apply this label to LGBT people who support "compromise" policies, such as those that find civil unions acceptable in place of same-sex marriage.[92]

Researcher Iain R. Williamson finds the term homophobia to be "highly problematic," but for reasons of continuity and consistency with the majority of other publications on the issue retains its use rather than using more accurate but obscure terminology.[8] The phrase internalized sexual stigma is sometimes used in place to represent internalized homophobia.[83] An internalized stigma arises when a person believes negative stereotypes about themselves, regardless of where the stereotypes come from. It can also refer to many stereotypes beyond sexuality and gender roles. Internalized homophobia can cause discomfort with and disapproval of one's own sexual orientation. Ego-dystonic sexual orientation or egodystonic homophobia, for instance, is a condition characterized by having a sexual orientation or an attraction that is at odds with one's idealized self-image, causing anxiety and a desire to change one's orientation or become more comfortable with one's sexual orientation. Such a situation may cause extreme repression of homosexual desires.[82] In other cases, a conscious internal struggle may occur for some time, often pitting deeply held religious or social beliefs against strong sexual and emotional desires. This discordance can cause clinical depression, and a higher rate of suicide among LGBT youth (up to 30 percent of non-heterosexual youth attempt suicide) has been attributed to this phenomenon.[89] Psychotherapy, such as gay affirmative psychotherapy, and participation in a sexual-minority affirming group can help resolve the internal conflicts, such as between religious beliefs and sexual identity.[83] Even informal therapies that address understanding and accepting of non-heterosexual orientations can prove effective.[89] Many diagnostic "Internalized Homophobia Scales" can be used to measure a person's discomfort with their sexuality and some can be used by people regardless of gender or sexual orientation. Critics of the scales note that they presume a discomfort with non-heterosexuality which in itself enforces heternormativity.[82][93]

Social

The fear of being identified as gay can be considered as a form of social homophobia. Theorists including Calvin Thomas and Judith Butler have suggested that homophobia can be rooted in an individual's fear of being identified as gay. Homophobia in men is correlated with insecurity about masculinity.[94][95] For this reason, homophobia is allegedly rampant in sports, and in the subculture of its supporters that is considered stereotypically male, such as association football and rugby.[96]

Nancy J. Chodorow states that homophobia can be viewed as a method of protection of male masculinity.[97] Various psychoanalytic theories explain homophobia as a threat to an individual's own same-sex impulses, whether those impulses are imminent or merely hypothetical. This threat causes repression, denial or reaction formation.[98]

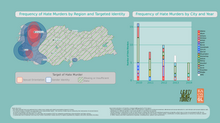

Distribution of attitude

Homophobia is not evenly distributed throughout society, but is more or less pronounced according to ethnicity, age, geographic location, race, sex, social class, education, partisan identification and religion.[13] According to UK HIV/AIDS charity AVERT, religious views, lack of homosexual feelings or experiences, and lack of interaction with gay people are strongly associated with such views.[99]

The anxiety of heterosexual individuals (particularly adolescents whose construction of heterosexual masculinity is based in part on not being seen as gay) that others may identify them as gay[100][101] has also been identified by Michael Kimmel as an example of homophobia.[102] The taunting of boys seen as eccentric (and who are not usually gay) is said to be endemic in rural and suburban American schools, and has been associated with risk-taking behavior and outbursts of violence (such as a spate of school shootings) by boys seeking revenge or trying to assert their masculinity.[103] Homophobic bullying is also very common in schools in the United Kingdom.[104] At least 445 LGBT Brazilians were either murdered or committed suicide in 2017.[105]

In some cases, the works of authors who merely have the word "Gay" in their name (Gay Talese, Peter Gay) or works about things also contain the name (Enola Gay) have been destroyed because of a perceived pro-homosexual bias.[106]

In the United States, attitudes vary on the basis of partisan identification. Republicans are far more likely than Democrats to have negative attitudes about gays and lesbians, according to surveys conducted by the National Election Studies from 2000 through 2004.[107] Homophobia also varies by region; statistics show that the Southern United States has more reports of anti-gay prejudice than any other region in the US.[108]

In a 1998 address, civil rights leader Coretta Scott King stated, "Homophobia is like racism and anti-Semitism and other forms of bigotry in that it seeks to dehumanize a large group of people, to deny their humanity, their dignity and personhood."[109] One study of white adolescent males conducted at the University of Cincinnati by Janet Baker[which?] has been used to argue that negative feelings towards gay people are also associated with other discriminatory behaviors.[110] According to the study, hatred of gay people, antisemitism, and racism are "likely companions".[110] Baker hypothesized "maybe it's a matter of power and looking down on all you think are at the bottom."[110] A study performed in 2007 in the UK for the charity Stonewall reports that up to 90 percent of the population support anti-discrimination laws protecting gay and lesbian people.[111]

Economic cost

There are at least two studies which indicate that homophobia may have a negative economic impact for the countries where it is widespread. In these countries there is a flight of their LGBT populations—with the consequent loss of talent—as well as an avoidance of LGBT tourism, that leaves the pink money in LGBT-friendlier countries. As an example, LGBT tourists contribute 6.8 billion dollars every year to the Spanish economy.[112]

As soon as 2005, an editorial from the New York Times related the politics of don't ask, don't tell in the US Army with the lack of translators from Arabic, and with the delay in the translation of Arabic documents, calculated to be about 120,000 hours at the time. Since 1998, with the introduction of the new policy, about 20 Arabic translators had been expelled from the Army, specifically during the years the US was involved in wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.[113]

M. V. Lee Badgett, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, presented in March 2014 in a meeting of the World Bank the results of a study about the economic impact of homophobia in India. Only in health expenses, caused by depression, suicide, and HIV treatment, India would have spent additional 23,100 million dollars due to homophobia. On top, there would be costs caused by violence, workplace loss, rejection of the family, and bullying at school, that would result in a lower education level, lower productivity, lower wages, worse health, and a lower life expectancy among the LGBT population.[114] In total, she estimated for 2014 in India a loss of up to 30,800 million dollars, or 1.7% of the Indian GDP.[112][115][116]

The LGBT activist Adebisi Alimi, in a preliminary estimation, has calculated that the economic loss due to homophobia in Nigeria is about 1% of its GDP. Taking into account that in 2015 homosexuality is still illegal in 36 of the 54 African countries, the money loss due to homophobia in the continent could amount to hundreds of millions of dollars every year.[112]

Another study regarding socioecological measurement of homophobia and its public health impact for 158 countries was conducted in 2018. It found that the prejudice against gay people has a worldwide economic cost of $119.1 billion. Economical loss in Asia was 88.29 billion dollars due to homophobia, and in Latin America & the Caribbean it was 8.04 billion dollars. Economical cost in East Asia and Middle Asia was 10.85 billion dollars. Economical cost in Middle East and North Africa was 16.92 billion dollars. The researcher suggested that a 1% decrease in the level of homophobia is correlated with a 10% increase in the gross domestic product per capita – though this does not imply causation.[117]

A 2018 study by The Williams Institute (UCLA School of Law) concludes that there is a positive correlation between LGBT inclusion and GDP per capita. According to this study, the legal rights of LGBT people have a bigger influence than the degree of acceptance in the society, but both effects reinforce each other.[118] A one-point increase in their LGBT Global Acceptance Index (GAI) showed an increase of $1,506 in GDP per capita, and one additional legal right was correlated with an increase of $1,694 in GDP per capita.[119]

Countermeasures

Most international human rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, condemn laws that make homosexual relations between consenting adults a crime. Since 1994, the United Nations Human Rights Committee has also ruled that such laws violated the right to privacy guaranteed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. In 2008, the Roman Catholic Church issued a statement which "urges States to do away with criminal penalties against [homosexual persons]." The statement, however, was addressed to reject a resolution by the UN Assembly that would have precisely called for an end of penalties against homosexuals in the world.[120] In March 2010, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe adopted a recommendation on measures to combat discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity, described by CoE Secretary General as the first legal instrument in the world dealing specifically with one of the most long-lasting and difficult forms of discrimination to combat.[121]

To combat homophobia, the LGBT community uses events such as gay pride parades and political activism (See gay pride). Cities across the word use crossings repainted in rainbow colors for their annual pride parades. The first permanent crossings have been put on roads in Lambeth, England.[122]

One form of organized resistance to homophobia is the International Day Against Homophobia (or IDAHO),[123] first celebrated 17 May 2005, in related activities in more than 40 countries.[124] The four largest countries of Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia) developed mass media campaigns against homophobia since 2002.[125]

In addition to public expression, legislation has been designed, controversially, to oppose homophobia, as in hate speech, hate crime, and laws against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Successful preventative strategies against homophobic prejudice and bullying in schools have included teaching pupils about historical figures who were gay, or who suffered discrimination because of their sexuality.[126]

Some argue that anti-LGBT prejudice is immoral and goes above and beyond the effects on that class of people. Warren J. Blumenfeld argues that this emotion gains a dimension beyond itself, as a tool for extreme right-wing conservatives and fundamentalist religious groups and as a restricting factor on gender-relations as to the weight associated with performing each role accordingly.[127] Furthermore, Blumenfeld in particular stated:

"Anti-gay bias causes young people to engage in sexual behavior earlier in order to prove that they are straight. Anti-gay bias contributed significantly to the spread of the AIDS epidemic. Anti-gay bias prevents the ability of schools to create effective honest sexual education programs that would save children's lives and prevent STDs (sexually transmitted diseases)."[127]

Drawing upon research by Arizona State University Professor Elizabeth Segal, University of Memphis professors Robin Lennon-Dearing and Elena Delavega argued in a 2016 article published in the Journal of Homosexuality that homophobia could be reduced through exposure (learning about LGBT experiences), explanation (understanding the different challenges faced by LGBT people), and experience (putting themselves in situations experienced by LGBT people by working alongside LGBT co-workers or volunteering at an LGBT community center).[128]

Criticism of meaning and purpose

Distinctions and proposed alternatives

Researchers have proposed alternative terms to describe prejudice and discrimination against LGBTQ people. Some of these alternatives show more semantic transparency while others do not include -phobia:

- Homoerotophobia, being a possible precursor term to homophobia, was coined by Wainwright Churchill and documented in Homosexual Behavior Among Males in 1967.

- The etymology of homophobia citing the union of homos and phobos is the basis for LGBT historian John Boswell's criticism of the term and for his suggestion in 1980 of the alternative homosexophobia.[129]

- Homonegativity is based on the term homonegativism used by Hudson and Ricketts in a 1980 paper; they coined the term for their research to avoid homophobia, which they regarded as being unscientific in its presumption of motivation.[130]

- Heterosexism refers to a system of negative attitudes, bias, and discrimination in favour of opposite-sex sexual orientation and relationships.[131] It can include the presumption that everyone is heterosexual or that opposite-sex attractions and relationships are the only norm[citation needed] and therefore superior.

- Sexual prejudice – Researcher at the University of California, Davis, Gregory M. Herek preferred sexual prejudice as being descriptive, free of presumptions about motivations, and lacking value judgments as to the irrationality or immorality of those so labeled.[132][133] He compared homophobia, heterosexism, and sexual prejudice, and, in preferring the third term, noted that homophobia was "probably more widely used and more often criticized." He also observed that "Its critics note that homophobia implicitly suggests that antigay attitudes are best understood as an irrational fear and that they represent a form of individual psychopathology rather than a socially reinforced prejudice."

Other names

Negative attitudes toward identifiable LGBT groups have similar yet specific names: lesbophobia is the intersection of homophobia and sexism directed against lesbians, gayphobia is the dislike or hatred of gay men, biphobia targets bisexuality and bisexual people, and transphobia targets transgender and transsexual people and gender variance or gender role nonconformity.[134][2][4][135]

Non-neutral phrasing

Use of homophobia, homophobic, and homophobe has been criticized as pejorative against LGBT rights opponents. Behavioral scientists William O'Donohue and Christine Caselles stated in 1993 that "as [homophobia] is usually used, [it] makes an illegitimately pejorative evaluation of certain open and debatable value positions, much like the former disease construct of homosexuality" itself, arguing that the term may be used as an ad hominem argument against those who advocate values or positions of which the user does not approve.[136]

Psychologists Gregory M. Herek and Beverly A. Greene also find fault with the term "homophobia:" "Technically, homophobia means fear of sameness, yet its usage implies a fear of homosexuals....the –phobia suffix implies a specific kind of fear... Fear or aversion may comprise one component of beliefs about homosexuality, but other factors are unquestionably important. Several alternative terms have been offered ...These include homonegativism (Hudson & Ricketts, 1980), homosexism (Hansen, 1982), and heterosexism (Herek, 1986a). Unfortunately, none has gained widespread acceptance."[137]

However, neutral use of the term has gained acceptance and usage over time since the 1990s. In 2017, the Associated Press Stylebook added an entry for "homophobia" and "homophobic" for the first time,[138] after having excluded it in 2012.[139] The entry says the terms are "acceptable in broad references or in quotations to the concept of fear or hatred of gays, lesbians and bisexuals."

Heterophobia

The term heterophobia is sometimes used to describe reverse discrimination towards heterosexuals.[140] The scientific use of heterophobia in sexology is restricted to a few researchers who question Alfred Kinsey's sex research.[141][142] To date, the existence or extent of heterophobia is mostly unrecognized by sexologists.[140] Beyond sexology, there is no consensus as to the meaning of the term because it is also used to mean "fear of the opposite", such as in Pierre-André Taguieff's The Force of Prejudice: On Racism and Its Doubles (2001). Referring to the debate on both meaning and use, SUNY lecturer Raymond J. Noonan stated:[140]

The term heterophobia is confusing for some people for several reasons. On the one hand, some look at it as just another of the many me-too social constructions that have arisen in the pseudoscience of victimology in recent decades. (Many of us recall John Money's 1995 criticism of the ascendancy of victimology and its negative impact on sexual science.) Others look at the parallelism between heterophobia and homophobia, and suggest that the former trivializes the latter... For others, it is merely a curiosity or parallel-construction word game. But for others still, it is part of both the recognition and politicization of heterosexuals' cultural interests in contrast to those of gays—particularly where those interests are perceived to clash.

Stephen M. White and Louis R. Franzini introduced the related term heteronegativism to refer to the range of negative feelings that some gay individuals may hold toward heterosexuals. This term is preferred to heterophobia because it does not imply extreme or irrational fear.[143] The Merriam-Webster dictionary of the English language defines heterophobia as "irrational fear of, aversion to, or discrimination against heterosexual people".[144]

See also

- Corrective rape

- Discrimination against non-binary people

- Faggot (slang)

- Gay panic defense

- Homosexual agenda

- Heteropatriarchy

- Homophobia in the African American community

- Homophobia in the Asian American community

- Homophobia in the Black British community

- Homosexuality and Citizenship in Florida (pamphlet)

- Lavender scare

- Liberal homophobia

- Minority stress

- Riddle scale

- Sexual repression

- Stop Murder Music

- Yogyakarta Principles

References

- ^ McCarty, J. "Teaching (hetero)sexuality: 1960s sexual education films in the United States". Queering the web: A practical, digital inquiry into the history of sexuality and gender. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Adams, Maurianne; Bell, Lee Anne; Griffin, Pat (2007). Teaching for diversity and social justice. Routledge. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-1-135-92850-6.

Because of the complicated interplay among gender identity, gender roles, and sexual identity, transgender people are often assumed to be lesbian or gay (See Overview: Sexism, Heterosexism, and Transgender Oppression). ... Because transgender identity challenges a binary conception of sexuality and gender, educators must clarify their own understanding of these concepts. ... Facilitators must be able to help participants understand the connections among sexism, heterosexism, and transgender oppression and the ways in which gender roles are maintained, in part, through homophobia.

- ^ a b David, Tracy J. (2008). "Homophobia and media representations of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people". In Renzetti, Claire M.; Edleson, Jeffrey L. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Interpersonal Violence. SAGE Publications. p. 338. ISBN 978-1-4522-6591-9.

In a culture of homophobia (an irrational fear of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender [GLBT] people), GLBT people often face a heightened risk of violence specific to their sexual identities.

- ^ a b Schuiling, Kerri Durnell; Likis, Frances E. (2011). Women's gynecologic health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-7637-5637-6.

Homophobia is an individual's irrational fear or hate of homosexual people. This may include bisexual or transgender persons, but sometimes the more distinct terms of biphobia or transphobia, respectively, are used.

- ^ *"homophobia". webster.com. 2008. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- "homophobia". Dictionary.com. 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- European Parliament resolution on homophobia in Europe (Strasbourg Final ed.). 18 January 2006. "A" point.

- "homophobia, n.2". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. June 2012.

Fear or hatred of homosexuals and homosexuality.

- McCormack, Mark (23 May 2013). The declining significance of homophobia. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-19-999094-8.

- ^ Newport, Frank (3 April 2015). "Religion, same-sex relationships and politics in Indiana and Arkansas". Gallup. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ Meyer, Doug. Violence against queer people: Race, class, gender, and the persistence of anti-LGBT discrimination. Rutgers University Press.

- ^ a b c d Williamson, I. R. (1 February 2000). "Internalized homophobia and health issues affecting lesbians and gay men". Health Education Research. 15 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1093/her/15.1.97. ISSN 0268-1153. PMID 10788206.

- ^ Frost, David M.; Meyer, Ilan H. (2009). "Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals". Journal of Counseling Psychology. 56 (1): 97–109. doi:10.1037/a0012844. PMC 2678796. PMID 20047016.

- ^ "FBI releases 2010 hate crime statistics" (Press release). FBI National Press Office. 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Potok, Mark; Smith, Janet (Winter 2010). "Anti-gay hate crimes: Doing the math". Intelligence Report. Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Anderson, Eric (17 June 2011). "Homophobia". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Herek, Gregory M. (April 2004). "Beyond 'homophobia': Thinking about sexual prejudice and stigma in the twenty-first century" (PDF). Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 1 (2): 6–24. doi:10.1525/srsp.2004.1.2.6. S2CID 145788359.

- ^ Bullough, Vern L. "Homophobia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2024.

- ^ "homophobia". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 25 June 2011.

- ^ "homophobia". American Heritage Dictionary. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013.

- ^ "homophobia". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Behavior: The homosexual: Newly visible, newly understood". Time. Vol. 94, no. 18. 31 October 1969. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013.

- ^ Smith, Kenneth T. (1971). "Homophobia: A tentative personality profile". Psychological Reports. 29 (3): 1091–4. doi:10.2466/pr0.1971.29.3f.1091. OCLC 100640283. PMID 5139344. S2CID 13323120.

- ^ a b Weinberg, George (1973) [1972]. Society and the healthy homosexual. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press Doubleday & Co. ISBN 978-0-385-05083-8. OCLC 434538701.

- ^ Freedman, Alfred M. (1 September 2000). "Recalling APA's historic step". APA News. ISSN 0033-2704. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ Macionis, John J.; Plummer, Kenneth (2005). Sociology: A global introduction (3rd ed.). Pearson Education. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-13-128746-4.

- ^ Longley, Clifford (28 February 1981). "Homosexuality best seen as a handicap, Dr Runcie says". The Times. London.

Let us recognize where the problem lies – in the dislike and distaste felt by many heterosexuals for homosexuals, a problem we have come to call homophobia

and Gledhill, Ruth (7 August 2008). "New light on Archbishop of Canterbury's view on homosexuality". The Times. London. - ^ Plummer, David (2016). One of the boys. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-71212-1.

- ^ "The Riddle homophobia scale". Archived from the original on 4 September 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2016. from Allies Committee website, Department of Student Life, Texas A&M University

- ^ Guindon, Mary H.; Green, Alan G.; Hanna, Fred J. (April 2003). "Intolerance and psychopathology: Toward a general diagnosis for racism, sexism, and homophobia". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 73 (2): 167–176. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.73.2.167. ISSN 1939-0025. PMID 12769238.

- ^ Isay, Richard A.; Sved, Margery; Klinger, Rochelle L.; Carter, Debbie R.; Kertzner, Robert M.; Akman, Jeffrey; Atkins, Daphne Lanette; Cabaj, Robert P.; Townsend, Mark H.; Ashley, Kenneth (2011) [1992]. "Position statement on homosexuality". American Psychiatric Association. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011.

- ^ West, Mona (12 July 2005). "Queer spirituality". Abilene, Texas: Metropolitan Community Churches. Archived from the original on 27 May 2007.

- ^ Bromberger, Brian (15 October 2015). "New book details Windsor Supreme Court victory". Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ McClain, Lisa (10 April 2019). "A thousand years ago, the Catholic Church paid little attention to homosexuality". The Conversation. Retrieved 20 April 2024.

- ^ "The "gay" princess di bible". 2 December 2008.

- ^ "Homosexual relations and the bible". Peace by Jesus. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Gagnon, Robert. "Dr. Robert A. J. Gagnon". robgagnon.net. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ a b "The sixth commandment". Catechism of the Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 10 September 2002.

- ^ Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life (7 February 2012). "Religion and attitudes toward same-sex marriage". Pewforum.org. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ Gilgoff, Dan (7 May 2012). "Biden's support for gay marriage matches most Catholics' views". CNN. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ "The difficulties of being gay in Iran". Deutsche Welle. 26 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Iran: Discrimination and violence against sexual minorities". Human Rights Watch. 15 December 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Iran: UN experts demand stay of execution for two women LGBT rights activists". news.un.org. 28 September 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b Ahmady, Kameel (2020). Forbidden tale: A comprehensive study on lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) in Iran. London: Mehri Publication. ISBN 978-1-64945-722-6. OCLC 1232824514.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (26 January 2022). "Afghanistan: Taliban target LGBT Afghans". Author. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Kumar, Ruchi (26 January 2022). "Lives of LGBTQ+ Afghans 'dramatically worse' under Taliban rule, finds survey". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Westcott, Ben (18 September 2021). "Angry and afraid, Afghanistan's LGBTQ community say they're being hunted down after Taliban takeover". CNN. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "2009 report on state sponsored homophobia" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2009.

- ^ "7 countries still put people to death for same-sex acts". International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 10 October 2007. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009.

- ^ "Homosexuality and Islam". ReligionFacts.com.

- ^ a b "Lesbian and gay rights in the world" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2011.

- ^ Eke, Steven (28 July 2005). "Iran 'must stop youth executions'". BBC News.

Human Rights Watch calls on Iran to end juvenile executions, after claims that two boys were executed for being gay.

- ^ Moore, Patrick (31 January 2006). Murder and hypocrisy. The Advocate. p. 37.

Homan, and organization for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender Iranians in exile, estimates that more than 4,000 gay Iranians have been executed in the country since the Islamic revolution of 1979.

- ^ Whitaker, Brian (18 March 2005). "Arrests at Saudi 'gay wedding'". The Observer. London.

Saudi executions are not systematically reported, and officials deny that the death penalty is applied for same-sex activity alone

- ^ "7 countries still put people to death for same-sex acts". International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 29 October 2009. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Fathi, Nazila (30 September 2007). "Despite denials, gays insist they exist, if quietly, in Iran". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Carroll, Aengus; Itaborahy, Lucas Paoli (May 2015). "State-sponsored homophobia: A world survey of laws: Criminalisation, protection and recognition of same-sex love" (10th ed.). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association.

- ^ Ellis-Petersen, Hannah (28 March 2019). "Brunei introduces death by stoning as punishment for gay sex". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ Aldrich, Robert, ed. (31 October 2006). Gay life and culture: A world history. Universe Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7893-1511-3. OCLC 74909268.

- ^ Ferran, Lee (13 June 2016). "Under ISIS: Where being gay is punished by death". ABC News.

- ^ "ISIS, many of their enemies share a homicidal hatred of gays". CBS News. 13 June 2016.

- ^ Bruce-Jones, Eddie; Itaborahy, Lucas Paoli (May 2011). "State-sponsored homophobia" (PDF). ilga.org. International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ Legman, G. (1966). The guilt of the Templars. New York: Basic Books. p. 11.

- ^ Crompton, Louis (2009). Homosexuality and civilization. Harvard University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-674-03006-0.

- ^ Crompton 2009, p. 217.

- ^ Kang, Wenqing (2009). "Introduction". Obsession: Male same-sex relations in China, 1900–1950. Hong Kong University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-962-209-981-4.

- ^ Francoeur, Robert T.; Noonan, Raymond J. (2004). The Continuum complete international encyclopedia of sexuality. The Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-1488-5.

- ^ "History of Chinese homosexuality". Shanghai Star. 1 April 2004. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- ^ Hazard, John Newbold (Spring 1965). "Unity and diversity in socialist law". Law and Contemporary Problems. 30 (2). Duke University School of Law: 270–290. doi:10.2307/1190515. JSTOR 1190515. OCLC 80991633.

- ^ "Persecution of Homosexuals in the Third Reich". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ Fenton, Siobhan (17 May 2016). "LGBT relationships are illegal in 74 countries, research finds". The Independent.

- ^ "Gay North Korea news & reports 2005". Global Gayz. Archived from the original on 18 October 2005. Retrieved 5 May 2006.

- ^ Spartacus International Gay Guide. Bruno Gmunder Verlag. 2007. p. 1217.

- ^ Lee, Julie Yoonnyung (20 March 2021). "North Korea's 'only openly gay defector' finds love". BBC. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Ember, Carol R.; Ember, Melvin (2004). Encyclopedia of sex and gender: Men and women in the world's cultures. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6. OCLC 54914021.

- ^ a b Epprecht, Marc (2004). Hungochani: The history of a dissident sexuality in southern Africa. Montreal. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-7735-2751-5. OCLC 54905608.

- ^ "Under African skies, Part I: 'Totally unacceptable to cultural norms'". Kaiwright.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2006.

- ^ Veit-Wild, Flora; Naguschewski, Dirk (2005). Body, sexuality, and gender. Rodopi. p. 93. ISBN 978-90-420-1626-2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Meldrum, Andrew (10 November 2003). "Canaan Banana, president jailed in sex scandal, dies". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ a b Noack, Rick (21 July 2019). "Polish towns advocate 'LGBT-free' zones while the ruling party cheers them on". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Vermes, Jason (27 July 2019). "Why 'LGBT-free zones' are on the rise in Poland". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Foster, Peter (9 August 2019). "Polish ruling party whips up LGBTQ hatred ahead of elections amid 'gay-free' zones and Pride march attacks". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ "Shocking footage of anti-gay groups". Irish Independent. 2 February 2014.

- ^ "Russia: Supreme Court bans "LGBT movement" as "extremist"". Human Rights Watch. 30 November 2023. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ Herek, Gregory M.; Cogan, Jeanine C.; Gillis, J. Roy; Glunt, Eric K. (1997). "Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men". Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association. 2 (1): 17–25. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.582.7247. OCLC 206392016.

- ^ a b c Adams, Henry E.; Wright, Lester W.; Lohr, Bethany A. (August 1996). "Is homophobia associated with homosexual arousal?". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 105 (3): 440–445. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.105.3.440. PMID 8772014. S2CID 8349682.

- American Psychological Association (August 1996). "New study links homophobia with homosexual arousal" (Press release). Archived from the original on 2 February 2004.

- ^ a b c Report of the American Psychological Association task force on appropriate therapeutic responses to sexual orientation (PDF). American Psychological Association. August 2009.[page needed]

- ^ Weinstein, Netta; Ryan, William S.; DeHaan, Cody R.; Przybylski, Andrew K.; Legate, Nicole; Ryan, Richard M. (2012). "Parental autonomy support and discrepancies between implicit and explicit sexual identities: Dynamics of self-acceptance and defense". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 102 (4): 815–832. doi:10.1037/a0026854. PMID 22288529. S2CID 804948.

- ^ University of Rochester (12 April 2012). "Is some homophobia self-phobia?". ScienceDaily (Press release). Archived from the original on 13 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ Cheval, Boris; Radel, Remi; Grob, Emmanuelle; Ghisletta, Paolo; Bianchi-Demicheli, Francesco; Chanal, Julien (May 2016). "Homophobia: An impulsive attraction to the same sex? Evidence from eye-tracking data in a picture-viewing task". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 13 (5): 825–834. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.165. PMID 27006197.

- ^ Cheval, Boris; Grob, Emmanuelle; Chanal, Julien; Ghisletta, Paolo; Bianchi-Demicheli, Francesco; Radel, Remi (October 2016). "Homophobia is related to a low interest in sexuality in general: An analysis of pupillometric evoked responses". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 13 (10): 1539–1545. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.07.013. PMID 27528498.

- ^ Marczyk, Jesse. "Homophobia isn't repressed homosexuality and there's no good reason to suspect it would be, either". Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers, LLC. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ a b c Gonsiorek, John C. (March 1988). "Mental health issues of gay and lesbian adolescents". Journal of Adolescent Health Care. 9 (2): 114–122. doi:10.1016/0197-0070(88)90057-5. PMID 3283088.

- ^ Martino, Wayne (1 January 2000). "Policing masculinities: Investigating the role of homophobia and heteronormativity in the lives of adolescent school boys". The Journal of Men's Studies. 8 (2): 213–236. doi:10.3149/jms.0802.213. S2CID 145712607.

- ^ Dreyer, Yolanda (5 May 2007). "Hegemony and the internalisation of homophobia caused by heteronormativity". HTS Teologiese Studies. 63 (1): 1–18. doi:10.4102/hts.v63i1.197. hdl:2263/2741.

- ^ Rostosky, Sharon Scales; Riggle, Ellen D. B.; Horne, Sharon G.; Miller, Angela D. (January 2009). "Marriage amendments and psychological distress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adults". Journal of Counseling Psychology. 56 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1037/a0013609. S2CID 43455275.

- ^ Shidlo, Ariel (1994). "Internalized Homophobia: Conceptual and Empirical Issues in Measurement". Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research, and clinical applications. pp. 176–205. doi:10.4135/9781483326757.n10. ISBN 978-0-8039-5312-3.

- ^ "Masculinity challenged, men prefer war and SUVs". Live Science. 2 August 2005.

- ^ "Homophobia and hip-hop". Independent Lens. PBS. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Dykes, John. "Fans' culture hard to change". Bangkok Post. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011.

- ^ Chodorow, Nancy J. (18 December 1998). Homophobia: Analysis of a 'permissible' prejudice (Speech). New York City: American Psychoanalytic Foundation. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ West, Donald James (1977). Homosexuality re-examined. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0812-1.

- ^ "Prejudice & attitudes to gay men & lesbians". avert.org. 23 June 2015.

- ^ Epstein, Debbie (1996). "Keeping them in their Place: Hetero/Sexist Harassment, Gender and the Enforcement of Heterosexuality". Sex, sensibility and the gendered body. pp. 202–221. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-24536-9_11. ISBN 978-0-333-65002-8.

- ^ Herek, Gregory M., ed. (1998). Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay issues. Vol. 4. Sage Publications. ISBN 978-0-8039-5385-7. OCLC 37721264.

- ^ Kimmel, Michael Scott (13 June 1994). "Masculinity as homophobia: Fear, shame and silence in the construction of gender identity". In Brod, Harry; Kaufman, Michael (eds.). Theorizing masculinities. Newbury Park, California: SAGE Publications. pp. 119–141. ISBN 978-1-5063-1964-3.

- ^ Kimmel, Michael Scott; Mahler, Matthew (2003). "Adolescent masculinity, homophobia, and violence: Random school shootings, 1982–2001". American Behavioral Scientist. 46 (10): 1439–58. doi:10.1177/0002764203046010010. OCLC 437621566. S2CID 141177806.

- ^ "How fair is Britain? the first Triennial Review". Equality and Human Rights Commission. Archived from the original on 15 October 2010. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- ^ Cowie, Sam (22 January 2018). "Violent deaths of LGBT people in Brazil hit all-time high". The Guardian.

- ^ Petras, Kathryn; Petras, Ross (2003). Unusually stupid Americans (A compendium of all American stupidity). New York: Villard Books. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-9658068-7-9.

- ^ Fried, Joseph (2008). Democrats and Republicans—rhetoric and reality: Comparing the voters in statistics and anecdotes. Algora Publishing. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-87586-605-5. OCLC 183179592.

- ^ Lyons, P. M. Jr.; Anthony, C. M.; Davis, K. M.; Fernandez, K.; Torres, A. N.; Marcus, D. K. (2005). "Police judgments of culpability and homophobia". Applied Psychology in Criminal Justice. 1 (1): 1–14. ISSN 1550-3550. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- ^ "The Legacy of & Memorial to Dr. King, MLK – Wesleyan University". www.wesleyan.edu. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ a b c "Homophobia, racism likely companions, study shows". Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. 10 January 1994. p. 12.

- ^ Muir, Hugh (23 May 2007). "Majority support gay equality rights, poll finds". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ a b c Smith, David (16 October 2015). "The hidden cost of homophobia in Africa". EconomyWatch.com. republished as Smith, David (16 October 2015). "The hidden cost of homophobia in Africa". Williams Institute. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019.

- ^ "The price of homophobia". The New York Times (Editorial). 20 January 2005. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ Alimi, Adebisi (19 June 2014). "The development costs of homophobia". Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ Badgett, M. V. Lee. Sexual minorities and development (PDF) (Report). The World Bank. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- ^ Westcott, Lucy (12 March 2014). "What homophobia costs a country's economy". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Lamontagne, Erik; d'Elbée, Marc; Ross, Michael W; Carroll, Aengus; Plessis, André du; Loures, Luiz (3 March 2018). "A socioecological measurement of homophobia for all countries and its public health impact". European Journal of Public Health. 28 (5): 967–972. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky023. PMID 29514190.

- ^ Badgett, M.V. Lee; Park, Andrew; Flores, Andrew (March 2018). Links between economic development and new measures of LGBT inclusion (PDF) (Report). Los Angeles: Williams Institute. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Global Acceptance Index". Williams Institute. UCLA School of Law. Retrieved 10 February 2020.[better source needed]

- ^ "Statement of the Holy See Delegation at the 63rd Session of the General Assembly of the United Nations on the Declaration on Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity". vatican.va. 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Council of Europe to advance human rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons" (Press release) (in English and French). Council of Europe. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "The UK's first rainbow crossing". BBC. 20 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ "Towards an international Day against Homophobia". International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 10 April 2004. Archived from the original on 17 December 2005.

- ^ "1st annual International Day Against Homophobia to be celebrated in over 40 countries on May 17" (Press release). 12 May 2005. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007.

- ^ Lyra, Paulo; et al. (2008). "PAHO/WHO | Campaigns against homophobia in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico". Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ^ Shepherd, Jessica (26 October 2010). "Lessons on gay history cut homophobic bullying in north London school". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- ^ a b Blumenfeld, Warren J. (1992). Homophobia: How we all pay the price. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-7919-5. OCLC 24544734.

- ^ Boswell, John (1980). Christianity, social tolerance, and homosexuality: Gay people in western Europe from the beginning of the Christian era to the fourteenth century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Hudson, WW; Ricketts, WA (1980). "A strategy for the measurement of homophobia". Journal of Homosexuality. 5 (4): 357–72. doi:10.1300/J082v05n04_02. OCLC 115532547. PMID 7204951.

- ^ Jung, Patricia Beattie; Smith, Ralph F. (1993). Heterosexism: An ethical challenge. State University of New York Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7914-1696-9.

- ^ Herek, Gregory M. (1990). "The context of anti-gay violence: Notes on cultural and psychological heterosexism". J Interpers Violence. 5 (3): 316–333. doi:10.1177/088626090005003006. S2CID 145678459.

- ^ Herek, Gregory M. (February 2000). "The psychology of sexual prejudice". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 9 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00051. S2CID 36963920.

- ^ Clauss-Ehlers, Caroline S. (2010). Encyclopedia of cross-cultural school psychology (2 ed.). Springer. p. 524. ISBN 978-0-387-71798-2.

- ^ Spijkerboer, Thomas (2013). Fleeing homophobia: Sexual orientation, gender identity and asylum. Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-134-09835-4.

Transgender people subjected to violence, in a range of cultural contexts, frequently report that transphobic violence is expressed in homophobic terms. The tendency to translate violence against a trans person to homophobia reflects the role of gender in attribution of homosexuality as well as the fact that hostility connected to homosexuality is often associated with the perpetrators' prejudices about particular gender practices and their visibility.

- ^ O'Donohue, William; Caselles, Christine (September 1993). "Homophobia: Conceptual, definitional, and value issues". J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 15 (3): 177–195. doi:10.1007/BF01371377. S2CID 144801673.

- ^ Greene, Beverly; Herek, Gregory M. (5 January 1994). Lesbian and gay psychology: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Psychological Perspectives on Lesbian & Gay Issues. New York: SAGE Publications. pp. 27, 28. ISBN 978-0-8039-5312-3.

- ^ Sopelsa, Brooke (27 March 2017). "AP stylebook embraces 'they' as a singular, gender-neutral pronoun". NBC News. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Byers, Dylan (26 November 2012). "AP nixes 'homophobia', 'ethnic cleansing'". Politico. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ a b c Noonan, Raymond J. (6 November 1999). "Heterophobia: The evolution of an idea". Dr. Ray Noonan's 1999 Conference Presentations. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ Reisman, Judith A.; Eichel, Edward W.; Muir, J. Gordon; Court, John Hugh (1990). Kinsey, sex and fraud: The indoctrination of a people, an investigation into the human sexuality research of Alfred C. Kinsey, Wardell B. Pomeroy, Clyde E. Martin, and Paul H. Gebhard. Lochinvar-Huntington House. ISBN 978-0-910311-20-5.[page needed]

- ^ The Complete Dictionary of Sexuality by Robert T. Francoeur[page needed]

- ^ White, Stephen M.; Franzini, Louis R. (24 February 1999). "Heteronegativism: The attitudes of gay men and lesbians toward heterosexuals". Journal of Homosexuality. 37 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1300/J082v37n01_05. PMID 10203070.

- ^ "heterophobia". Merriam-Webster (Online ed.). Retrieved 15 March 2022.

Further reading

- Social Psychological and Personality Science (26 December 2019). "Gender norms affect attitudes towards gay men and lesbian women globally" (Press release). Washington, DC: EurekAlert!.

- Herek, Gregory M. (2001). "Sexual prejudice: Understanding homophobia and heterosexism". psychology.ucdavis.edu. Archived from the original on 8 November 2007.

- Norton, Rictor; Crew, Louie (November 1974). "The homophobic imagination: An editorial". College English. 36 (3). The National Council of Teachers of English: 272–290. doi:10.58680/ce197417314. ISSN 0010-0994. JSTOR 374839. Archived from the original on 13 April 2006.

- Boteach, Shmuley (16 October 2010). "Homophobia is itself an abomination". The Huffington Post.

- Echarry, Irina (19 May 2009). "Homophobia is the problem, not gays". Havana Times.

- Ahmady, Kameel (2020). Forbidden tale: A comprehensive study on lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) in Iran. London: Mehri Publication. ISBN 978-1-64945-722-6. OCLC 1232824514.

External links

- Rockway Institute Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine at Alliant International University (LGBT research in the public interest)

- European Parliament resolution on homophobia in Europe, European Parliament, 2006

- Campaigns against Homophobia in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, Pan American Health Organization, 2008

- Discriminatory laws and practices and acts of violence against individuals based on their sexual orientation and gender identity, United Nations Human Rights Council, 2011

- Living Free and Equal: What States Are Doing to Tackle Violence and Discrimination against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People, United Nations, 2016

- Breaking the Silence: Criminalisation of Lesbians and Bisexual Women and its Impacts. Human Dignity Trust, May 2016.

- In Some Countries, Being Gay Or Lesbian Can Land You In Prison...Or Worse. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 2020