History of Libya

| History of Libya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Libya's history involves its rich mix of ethnic groups, including the indigenous Berbers/Amazigh people. Amazigh have been present throughout the entire history of the country. For most of its history, Libya has been subjected to varying degrees of foreign control, from Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The history of Libya comprises six distinct periods: Ancient Libya, the Roman era, the Islamic era, Ottoman rule, Italian rule, and the Modern era.

Prehistoric and Berber Libya

[edit]

Tens of thousands of years ago, the Sahara Desert, which now covers roughly 90% of Libya, was lush with green vegetation. It was home to lakes, forests, diverse wildlife and a temperate Mediterranean climate. Archaeological evidence indicates that the coastal plain was inhabited by Neolithic peoples from as early as 8000 BCE. These peoples were perhaps drawn by the climate, which enabled their culture to grow, subsisting on the domestication of cattle and the cultivation of crops.[1]

Egyptian inscriptions from the Old Kingdom are the oldest available documentation of the Berber people. The inscriptions record Berber tribes raiding the Nile Delta.[2] Rock paintings at Wadi Mathendous and the mountainous region of Jebel Acacus are the best sources of information about prehistoric Libya, and the pastoralist culture that settled there. The paintings reveal that the Libyan Sahara contained rivers, grassy plateaus and an abundance of wildlife such as giraffes, elephants and crocodiles.[3]

The onset of the Piora Oscillation's intense aridification resulted in the "green Sahara" rapidly transforming into the Sahara Desert. Dispersal in Africa from the Atlantic coast to the Siwa Oasis in Egypt seems to have followed, due to climatic changes which caused increasing desertification.

The African ancestors of the Berber people are assumed to have spread into the area by the Late Bronze Age. The earliest known name of such a tribe is that of the Garamantes, who were based in Germa, southern Libya. The Garamantes were a Saharan people of Berber origin who used an elaborate underground irrigation system; they were probably present as tribal people in the Fezzan by about 1000 BCE, and were a local power in the Sahara between 500 BCE and 500 CE. By the time of contact with the Phoenicians, the first of the Semitic civilizations to arrive in Libya from the East, the Lebu, Garamantes, Berbers and other tribes that lived in the Sahara were already well established.[citation needed]

Phoenician and Greek Libya

[edit]

The Phoenicians were some of the first to establish coastal trading posts in Libya, when the merchants of Tyre (in present-day Lebanon) developed commercial relations with the various Berber tribes and made treaties with them to ensure their cooperation in the exploitation of raw materials.[4][5] By the 5th century BCE, the greatest of the Phoenician colonies, Carthage, had extended its hegemony across much of North Africa, where a distinctive civilization, known as Punic, came into being. Punic settlements on the Libyan coast included Oea (later Tripoli), Libdah (later Leptis Magna) and Sabratha. These cities were in an area that was later called Tripolis, or "Three Cities", from which Libya's modern capital Tripoli takes its name.

In 630 BCE, the Ancient Greeks colonized Eastern Libya and founded the city of Cyrene.[6] Within 200 years, four more important Greek cities were established in the area that became known as Cyrenaica: Barce (later Marj); Euhesperides (later Berenice, present-day Benghazi); Taucheira (later Arsinoe, present-day Taucheria); Balagrae (later Bayda and Beda Littoria under Italian occupation, present-day Bayda); and Apollonia (later Susa), the port of Cyrene.[7] Together with Cyrene, they were known as the Pentapolis (Five Cities). Cyrene became one of the greatest intellectual and artistic centers of the Greek world, and was famous for its medical school, learned academies, and architecture. The Greeks of the Pentapolis resisted encroachments by the Ancient Egyptians from the East, as well as by the Carthaginians from the West.

Achaemenid and Ptolemaic Libya

[edit]

In 525 BCE the Persian army of Cambyses II overran Cyrenaica, which for the next two centuries remained under Persian or Egyptian rule. Alexander was greeted by the Greeks when he entered Cyrenaica in 331 BCE, and Eastern Libya again fell under the control of the Greeks, this time as part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Later, a federation of the Pentapolis was formed that was customarily ruled by a king drawn from the Ptolemaic royal house.

Roman Libya

[edit]After the fall of Carthage, the Romans did not immediately occupy Tripolitania (the region around Tripoli), but left it under control of the Berber kings of Numidia, until the coastal cities asked and obtained its protection.[8] Ptolemy Apion, the last Greek ruler, bequeathed Cyrenaica to Rome, which formally annexed the region in 74 BCE and joined it to Crete as a Roman province. During the Roman civil wars Tripolitania (still not formally annexed) and Cyrenaica sustained Pompey and Marc Antony against respectively Caesar and Octavian.[8][9] The Romans completed the conquest of the region under Augustus, occupying northern Fezzan ("Fasania") with Cornelius Balbus Minor.[10] As part of the Africa Nova province, Tripolitania was prosperous,[8] and reached a golden age in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when the city of Leptis Magna, home to the Severan dynasty, was at its height.[8] On the other side, Cyrenaica's first Christian communities were established by the time of the Emperor Claudius[9] but was heavily devastated during the Diaspora revolt,[11] and almost depopulated of Greeks and Jews alike,[12] and, although repopulated by Trajan with military colonies,[11] from then started its decadence.[9]

Regardless, for more than 400 years Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were part of a cosmopolitan state whose citizens shared a common language, legal system, and Roman identity. Roman ruins like those of Leptis Magna and Sabratha, extant in present-day Libya, attest to the vitality of the region, where populous cities and even smaller towns enjoyed the amenities of urban life—the forum, markets, public entertainments, and baths—found in every corner of the Roman Empire. Merchants and artisans from many parts of the Roman world established themselves in North Africa, but the character of the cities of Tripolitania remained decidedly Punic and, in Cyrenaica, Greek. Tripolitania was a major exporter of olive oil,[13] as well as a center for the trade of ivory and wild animals[13] conveyed to the coast by the Garamantes, while Cyrenaica remained an important source of wines, drugs, and horses. The bulk of the population in the countryside consisted of Berber farmers, who in the west were thoroughly "romanized" in language and customs.[14] Until the 10th century the African Romance remained in use in some Tripolitanian areas, mainly near the Tunisian border.[15]

The decline of the Roman Empire saw the classical cities fall into ruin, a process hastened by the Vandals' destructive sweep though North Africa in the 5th century. The region's prosperity had shrunk under Vandal domination, and the old Roman political and social order, disrupted by the Vandals, could not be restored. In outlying areas neglected by the Vandals,[16] the inhabitants had sought the protection of tribal chieftains and, having grown accustomed to their autonomy, resisted re-assimilation into the imperial system.[16]

When the Empire returned (now as East Romans) as part of Justinian's reconquests of the 6th century, efforts were made to strengthen the old cities, but it was only a last gasp before they collapsed into disuse. Cyrenaica, which had remained an outpost of the Byzantine Empire during the Vandal period, also took on the characteristics of an armed camp. Unpopular Byzantine governors imposed burdensome taxation to meet military costs, while the towns and public services—including the water system—were left to decay. Byzantine rule in Africa did prolong the Roman ideal of imperial unity there for another century and a half however, and prevented the ascendancy of the Berber nomads in the coastal region. By the beginning of the 7th century, Byzantine control over the region was weak, Berber rebellions were becoming more frequent, and there was little to oppose Muslim invasion.[17]

Islamic Libya

[edit]

Tenuous Byzantine control over Libya was restricted to a few poorly defended coastal strongholds, and as such, the Arab horsemen who first crossed into the Pentapolis of Cyrenaica in September 643 CE encountered little resistance. Under the command of 'Amr ibn al-'As, the armies of Islam conquered Cyrenaica, and renamed the Pentapolis, Barqa. They took also Tripoli, but after destroying the Roman walls of the city and getting a tribute they withdrew.[18] In 647 an army of 40,000 Arabs, led by Abdullah ibn Saad, the foster-brother of Caliph Uthman, penetrated deep into Western Libya and took Tripoli from the Byzantines definitively.[18] From Barqa, the Fezzan was conquered by Uqba ibn Nafi in 663 and Berber resistance was overcome. During the following centuries, Libya came under the rule of several Islamic dynasties, under various levels of autonomy from Ummayad, Abbasid and Fatimid caliphates of the time. Arab rule was easily imposed in the coastal farming areas and on the towns, which prospered again under Arab patronage. Townsmen valued the security that permitted them to practice their commerce and trade in peace, while the Punicized farmers recognized their affinity with the Semitic Arabs to whom they looked to protect their lands.[citation needed] In Cyrenaica, Monophysite adherents of the Coptic Church had welcomed the Muslim Arabs as liberators from Byzantine oppression. The Berber tribes of the hinterland accepted Islam, however they resisted Arab political rule.[19]

For the next several decades, Libya was under the purview of the Umayyad Caliph of Damascus until the Abbasids overthrew the Umayyads in 750, and Libya came under the rule of Baghdad. When Caliph Harun al-Rashid appointed Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab as his governor of Ifriqiya in 800, Libya enjoyed considerable local autonomy under the Aghlabid dynasty. The Aghlabids were among the most attentive Islamic rulers of Libya; they brought about a measure of order to the region, and restored Roman irrigation systems, which brought prosperity to the area from the agricultural surplus. By the end of the 9th century, the Shiite Fatimids controlled Western Libya from their capital in Mahdia, before they ruled the entire region from their new capital of Cairo in 972 and appointed Bologhine ibn Ziri as governor. During Fatimid rule, Tripoli thrived on the trade in slaves and gold brought from the Sudan and on the sale of wool, leather, and salt shipped from its docks to Italy in exchange for wood and iron goods. Ibn Ziri's Berber Zirid dynasty ultimately broke away from the Shiite Fatimids, and recognised the Sunni Abbasids of Baghdad as rightful Caliphs. In retaliation, the Fatimids brought about the migration of thousands from two troublesome Arab Bedouin tribes, the Banu Sulaym and Banu Hilal to North Africa. This act drastically altered the fabric of the Libyan countryside, and cemented the cultural and linguistic Arabisation of the region.[8] Ibn Khaldun noted that the lands ravaged by Banu Hilal invaders had become completely arid desert.[20]

Zirid rule in Tripolitania was short-lived though, and already in 1001 the Berbers of the Banu Khazrun broke away. Tripolitania remained under their control until 1146, when the region was overtaken by the Normans of Sicily.[21] The latter appointed a governor over it called Rafi Ibn Matruh, who established a kingdom and ruled under Roger I and his son Roger II until he revolted against him in the year 1158. The inhabitants of Tripoli revolted against him one year, and after the Almohads expelled the Normans from Mahdia, he pledged allegiance to the Almohads and remained governor of Tripoli until he asked for an exemption from it and traveled to Alexandria and died there.[22] For the next 50 years, Tripolitania was the scene of numerous battles between the Almohad rulers and insurgents of the Banu Ghaniya. Later, a general of the Almohads, Muhammad ibn Abu Hafs, ruled Libya from 1207 to 1221 before the later establishment of a Tunisian Hafsid dynasty[21] independent from the Almohads. in the period of Hafsids the emirate of banu talis established in the city of bani walid and ruled the city until the Ottoman conquest. The Hafsids ruled Tripolitania for nearly 300 years, and established significant trade with the city-states of Europe. Hafsid rulers also encouraged art, literature, architecture and scholarship. Ahmad Zarruq was one of the most famous Islamic scholars to settle in Libya, and did so during this time. By the 16th century however, the Hafsids became increasingly caught up in the power struggle between Spain and the Ottoman Empire. After a successful invasion of Tripoli by Habsburg Spain in 1510,[21] and its handover to the Knights of St. John, the Ottoman admiral Sinan Pasha finally took control of Libya in 1551.[21]

Ottoman Libya

[edit]

After a successful invasion by the Habsburgs of Spain in the early 16th century, Charles V entrusted its defense to the Knights of St. John in Malta. Lured by the piracy that spread through the Maghreb coastline, adventurers such as Barbarossa and his successors consolidated Ottoman control in the central Maghreb. The Ottoman Turks conquered Tripoli in 1551 under the command of Sinan Pasha. In the next year his successor Turgut Reis was named the Bey of Tripoli and later Pasha of Tripoli in 1556. As Pasha, he adorned and built up Tripoli, making it one of the most impressive cities along the North African coast.[23] By 1565, administrative authority as regent in Tripoli was vested in a pasha appointed directly by the sultan in Constantinople. In the 1580s, the rulers of Fezzan gave their allegiance to the sultan, and although Ottoman authority was absent in Cyrenaica, a bey was stationed in Benghazi late in the next century to act as agent of the government in Tripoli.[9]

In time, real power came to rest with the pasha's corps of janissaries, a self-governing military guild, and in time the pasha's role was reduced to that of ceremonial head of state.[21] Mutinies and coups were frequent, and in 1611 the deys staged a coup against the pasha, and Dey Sulayman Safar was appointed as head of government. For the next hundred years, a series of deys effectively ruled Tripolitania, some for only a few weeks, and at various times the dey was also pasha-regent. The regency governed by the dey was autonomous in internal affairs and, although dependent on the sultan for fresh recruits to the corps of janissaries, his government was left to pursue a virtually independent foreign policy as well. The two most important Deys were Mehmed Saqizli (r. 1631–49) and Osman Saqizli (r. 1649–72), both also Pasha, who ruled effectively the region.[24] The latter conquered also Cyrenaica.[24]

Tripoli was the only city of size in Ottoman Libya (then known as Tripolitania Eyalet) at the end of the 17th century and had a population of about 30,000. The bulk of its residents were Moors, as city-dwelling Arabs were then known. Several hundred Turks and renegades formed a governing elite, a large portion of which were kouloughlis (lit. sons of servants—offspring of Turkish soldiers and Arab women); they identified with local interests and were respected by locals. Jews and Moriscos were active as merchants and craftsmen and a small number of European traders also frequented the city. European slaves and large numbers of enslaved blacks transported from Sudan were also a feature of everyday life in Tripoli. In 1551, Turgut Reis enslaved almost the entire population of the Maltese island of Gozo, some 6,300 people, sending them to Libya.[25] The most pronounced slavery activity involved the enslavement of black Africans who were brought via trans-Saharan trade routes. Even though the slave trade was officially abolished in Tripoli in 1853, in practice it continued until the 1890s.[26]

Lacking direction from the Ottoman government, Tripoli lapsed into a period of military anarchy during which coup followed coup and few deys survived in office more than a year. One such coup was led by Turkish officer Ahmed Karamanli.[24] The Karamanlis ruled from 1711 until 1735 mainly in Tripolitania, but had influence in Cyrenaica and Fezzan as well by the mid 18th century. Ahmed was a Janissary and popular cavalry officer.[24] He murdered the Ottoman Dey of Tripolitania and seized the throne in 1711.[24] After persuading Sultan Ahmed III to recognize him as governor, Ahmed established himself as pasha and made his post hereditary. Though Tripolitania continued to pay nominal tribute to the Ottoman padishah, it otherwise acted as an independent kingdom. Ahmed greatly expanded his city's economy, particularly through the employment of corsairs (pirates) on crucial Mediterranean shipping routes; nations that wished to protect their ships from the corsairs were forced to pay tribute to the pasha. Ahmad's successors proved to be less capable than himself, however, the region's delicate balance of power allowed the Karamanli to survive several dynastic crises without invasion. The Libyan Civil War of 1791–1795 occurred in those years. In 1793, Turkish officer Ali Pasha deposed Hamet Karamanli and briefly restored Tripolitania to Ottoman rule. However, Hamet's brother Yusuf (r. 1795–1832) reestablished Tripolitania's independence.

In the early 19th century war broke out between the United States and Tripolitania, and a series of battles ensued in what came to be known as the First Barbary War and the Second Barbary War. By 1819, the various treaties of the Napoleonic Wars had forced the Barbary states to give up piracy almost entirely, and Tripolitania's economy began to crumble. As Yusuf weakened, factions sprung up around his three sons; though Yusuf abdicated in 1832 in favor of his son Ali II, civil war soon resulted. Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II sent in troops ostensibly to restore order, but instead deposed and exiled Ali II, marking the end of both the Karamanli dynasty and an independent Tripolitania.[27] Anyway, order was not recovered easily, and the revolt of the Libyan under Abd-El-Gelil and Gûma ben Khalifa lasted until the death of the latter in 1858.[27]

The second period of direct Ottoman rule saw administrative changes, and what seemed as greater order in the governance of the three provinces of Libya. It would not be long before the Scramble for Africa and European colonial interests set their eyes on the marginal Turkish provinces of Libya. The Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II twice sent his aide-de-camp Azmzade Sadik El Mueyyed to meet Sheikh Senussi to cultivate positive relations and counter the West European scramble for Africa.[28] Reunification came about through the unlikely route of an invasion (Italo-Turkish War, 1911–1912) and occupation starting from 1911 when Italy simultaneously turned the three regions into colonies.[29]

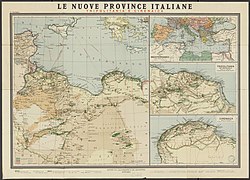

Italian Libya

[edit]

From 1912 to 1927, the territory of Libya was known as Italian North Africa. From 1927 to 1934, the territory was split into two colonies, Italian Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitania, run by Italian governors. Some 150,000 Italians settled in Libya, constituting roughly 20% of the total population.[30]

In 1934, Italy adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Greeks for all of North Africa, except Egypt) as the official name of the colony (made up of the three provinces of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan). Idris al-Mahdi as-Senussi (later King Idris I), Emir of Cyrenaica, led Libyan resistance to Italian occupation between the two world wars. Ilan Pappe estimates that between 1928 and 1932 the Italian military "killed half the Bedouin population (directly or through disease and starvation in camps)".[31] Italian historian Emilio Gentile sets to about 50,000 the number of victims of the repression.[32]

In 1934, the political entity called "Libya" was created by governor Balbo with capital Tripoli.[33] The Italians emphasized infrastructure improvements and public works. In particular, they hugely expanded Libyan railway and road networks from 1934 to 1940, building hundreds of kilometers of new roads and railways and encouraging the establishment of new industries and dozens of new agricultural villages.

During WW2, since June 1940 Libya was at the center of destructive fighting between the Axis and the British empire: the Allies conquered from Italy all of Libya only by February 1943.

From 1943 to 1951, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were under British military administration, while the French controlled Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal of some aspects of foreign control in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.[34]

Kingdom

[edit]

On 21 November 1949, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before 1 January 1952. Idris represented Libya in the subsequent UN negotiations. On 24 December 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King Idris, Libya's only monarch.

1951 also saw the enactment of the first Libyan Constitution. The Libyan National Assembly drafted the Constitution and passed a resolution accepting it in a meeting held in the city of Benghazi on Sunday, 6th Muharram, Hegiras 1371: 7 October 1951. Mohamed Abulas’ad El-Alem, President of the National Assembly and the two vice-presidents of the National Assembly, Omar Faiek Shennib and Abu Baker Ahmed Abu Baker executed and submitted the Constitution to King Idris following which it was published in the Official Gazette of Libya.[35]

The enactment of the Libyan Constitution was significant in that it was the first piece of legislation to formally entrench the rights of Libyan citizens following the post-war creation of the Libyan nation state. Following on from the intense UN debates during which Idris had argued that the creation of a single Libyan state would be of benefit to the regions of Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica, the Libyan government was keen to formulate a constitution which contained many of the entrenched rights common to European and North American nation states. Though not creating a secular state – Article 5 proclaims Islam the religion of the State – the Libyan Constitution did formally set out rights such as equality before the law as well as equal civil and political rights, equal opportunities, and an equal responsibility for public duties and obligations, "without distinction of religion, belief, race, language, wealth, kinship or political or social opinions" (Article 11).

During this period, Britain was involved in extensive engineering projects in Libya and was also the country's biggest supplier of arms. The United States also maintained the large Wheelus Air Base in Libya.[36]

Arab Republic and Jamahiriya

[edit]

On 1 September 1969, a small group of military officers led by 27-year-old army officer Muammar Gaddafi staged a coup d'état against King Idris, launching the Libyan Revolution.[37] Gaddafi was referred to as the "Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution" in government statements and the official Libyan press.[38]

On the birthday of Muhammad in 1973, Gaddafi delivered a "Five-Point Address". He announced the suspension of all existing laws and the implementation of Sharia. He said that the country would be purged of the "politically sick". A "people's militia" would "protect the revolution". There would be an administrative revolution, and a cultural revolution. Gaddafi set up an extensive surveillance system. 10 to 20 percent of Libyans worked in surveillance for the Revolutionary committees, which monitored activities in government, in factories, and in the education sector.[39] Gaddafi executed dissidents publicly and the executions were often rebroadcast on state television channels.[39][40] Gaddafi employed his network of diplomats and recruits to assassinate dozens of critical refugees around the world. Amnesty International listed at least 25 assassinations between 1980 and 1987.[39][41]

In 1977, Libya officially became the "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya". Gaddafi officially passed power to the General People's Committees and henceforth claimed to be no more than a symbolic figurehead,[42] but domestic and international critics claimed the reforms gave him virtually unlimited power. Dissidents against the new system were not tolerated, with punitive actions including capital punishment authorized by Gaddafi himself.[43] The new "jamahiriya" governance structure he established was officially referred to as a form of direct democracy,[44] though the government refused to publish election results.[45] Later that same year, Libya and Egypt fought a four-day border war that came to be known as the Libyan-Egyptian War, both nations agreed to a ceasefire under the mediation of the Algerian president Houari Boumediène.[46] In February 1977, Libya began to provide military supplies to Goukouni Oueddei and the People's Armed Forces in Chad. The Chadian–Libyan conflict began in earnest when Libya's support of rebel forces in northern Chad escalated into an invasion. Much of the country's income from oil, which soared in the 1970s, was spent on arms purchases and on sponsoring dozens of rebels groups around the world.[47][48][49] An airstrike failed to kill Gaddafi in 1986. Libya was accused in the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland and the 1989 bombing of UTA Flight 772 over Chad and Niger; Libya was finally put under United Nations sanctions in 1992. Gaddafi financed various other groups from anti-nuclear movements to Australian trade unions.[50]

From 1977 onward, per capita income in the country rose to more than US$11,000, the fifth-highest in Africa,[51] while the Human Development Index became the highest in Africa and greater than that of Saudi Arabia.[52] This was achieved without borrowing any foreign loans, keeping Libya debt-free.[53] In addition, the country's literacy rate rose from 10% to 90%, life expectancy rose from 57 to 77 years, employment opportunities were established for migrant workers, and welfare systems were introduced that allowed access to free education, free healthcare, and financial assistance for housing. The Great Manmade River was also built to allow free access to fresh water across large parts of the country.[52] In addition, financial support was provided for university scholarships and employment programs.[54]

Gaddafi doubled the minimum wage, introduced statutory price controls, and implemented compulsory rent reductions of between 30 and 40%. Gaddafi also wanted to combat the strict social restrictions that had been imposed on women by the previous regime, establishing the Revolutionary Women's Formation to encourage reform. In 1970, a law was introduced affirming equality of the sexes and insisting on wage parity. In 1971, Gaddafi sponsored the creation of a Libyan General Women's Federation. In 1972, a law was passed criminalizing the marriage of any females under the age of sixteen and ensuring that a woman's consent was a necessary prerequisite for a marriage.[55]

Gaddafi assumed the honorific title of "King of Kings of Africa" in 2008 as part of his campaign for a United States of Africa.[56] By the early 2010s, in addition to attempting to assume a leadership role in the African Union, Libya was also viewed as having formed closer ties with Italy, one of its former colonial rulers, than any other country in the European Union.[57] The eastern parts of the country have been "ruined" due to Gaddafi's economic theories, according to The Economist.[58][59]

2011 uprising and the First Civil War

[edit]

After popular movements overturned the rulers of Tunisia and Egypt, its immediate neighbors to the west and east, Libya experienced a full-scale revolt beginning on 17 February 2011.[60] By 20 February, the unrest had spread to Tripoli. In the early hours of 21 February 2011, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, oldest son of Muammar Gaddafi, spoke on Libyan television of his fears that the country would fragment and be replaced by "15 Islamic fundamentalist emirates" if the uprising engulfed the entire state. He admitted that "mistakes had been made" in quelling recent protests and announced plans for a constitutional convention, but warned that the country's economic wealth and recent prosperity was at risk and warned of "rivers of blood" if the protests continued.[61][62]

On 27 February 2011, the National Transitional Council was established under the stewardship of Mustafa Abdul Jalil, Gaddafi's former justice minister, to administer the areas of Libya under rebel control. This marked the first serious effort to organize the broad-based opposition to the Gaddafi regime. While the council was based in Benghazi, it claimed Tripoli as its capital.[63] Hafiz Ghoga, a human rights lawyer, later assumed the role of spokesman for the council.[64] On 10 March 2011, France became the first state to officially recognise the council as the legitimate representative of the Libyan people.[65][66]

By early March 2011, some parts of Libya had tipped out of Gaddafi's control, coming under the control of a coalition of opposition forces, including soldiers who decided to support the rebels. Eastern Libya, centered on the port city of Benghazi, was said to be firmly in the hands of the opposition, while Tripoli and its environs remained in dispute.[67][68][69] Pro-Gaddafi forces were able to respond militarily to rebel pushes in Western Libya and launched a counterattack along the coast toward Benghazi, the de facto centre of the uprising.[70] The town of Zawiya, 48 kilometres (30 mi) from Tripoli, was bombarded by Air Force planes and Army tanks and seized by Jamahiriya troops, "exercising a level of brutality not yet seen in the conflict".[71]

In several public appearances, Gaddafi threatened to destroy the protest movement, and Al Jazeera and other agencies reported his government was arming pro-Gaddafi militiamen to kill protesters and defectors against the regime in Tripoli.[72] Organs of the United Nations, including United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon[73] and the United Nations Human Rights Council, condemned the crackdown as violating international law, with the latter body expelling Libya outright in an unprecedented action urged by Libya's own delegation to the UN.[74][75] The United States imposed economic sanctions against Libya,[76] followed shortly by Australia,[77] Canada[78] and the United Nations Security Council, which also voted to refer Gaddafi and other government officials to the International Criminal Court for investigation.[79][80]

On 17 March 2011 the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1973 with a 10–0 vote and five abstentions. The resolution sanctioned the establishment of a no-fly zone and the use of "all means necessary" to protect civilians within Libya.[81]

Shortly afterwards, Libyan Foreign Minister Moussa Koussa stated that "Libya has decided an immediate ceasefire and an immediate halt to all military operations".[82]

On 19 March, the first Allied act to secure the no-fly zone began when French military jets entered Libyan airspace on a reconnaissance mission heralding attacks on enemy targets.[83] Allied military action to enforce the ceasefire commenced the same day when a French aircraft opened fire and destroyed a vehicle on the ground. French jets also destroyed five tanks belonging to the Gaddafi regime.[83] The United States and United Kingdom launched attacks on over 20 "integrated air defense systems" using more than 110 Tomahawk cruise missiles during operations Odyssey Dawn and Ellamy.[84]

On 27 June 2011, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Gaddafi, alleging that Gaddafi had been personally involved in planning and implementing "a policy of widespread and systematic attacks against civilians and demonstrators and dissidents".[85]

By 22 August 2011, rebel fighters had entered Tripoli and occupied Green Square,[86] which they renamed to its original name, Martyrs' Square in honour of those killed during the Italian occupation. Meanwhile, Gaddafi asserted that he was still in Libya and would not concede power to the rebels.[86]

On 16 September 2011, the U.N. General Assembly approved a request from the National Transitional Council to accredit envoys of the country's interim controlling body as Tripoli's sole representatives at the UN, effectively recognising the National Transitional Council as the legitimate holder of that country's UN seat.[87]

The National Transitional Council had been plagued by internal divisions during its tenure as Libya's interim governing authority. It postponed the formation of a caretaker, or "interim" government on several occasions during the period prior to the death of Muammar Gaddafi in his hometown of Sirte on 20 October 2011.[88][89] Mustafa Abdul Jalil led the National Transitional Council and was generally considered to be the principal leadership figure. Mahmoud Jibril served as the NTC's de facto head of government from 5 March 2011 through the end of the war, but he announced he would resign after Libya was declared to have been "liberated" from Gaddafi's rule.[90]

The "liberation" of Libya was celebrated on 23 October 2011, and Jibril announced that consultations were under way to form an interim government within one month, followed by elections for a constitutional assembly within eight months and parliamentary and presidential elections to be held within a year after that.[91] He stepped down as expected the same day and was succeeded by Ali Tarhouni.[92] At least 30,000 Libyans died in the civil war.[93]

Transition and the Second Civil War

[edit]After the First Civil War, the National Transitional Council (NTC) has been responsible for the transition of the administration of the governing of Libya. The "liberation" of Libya was celebrated on 23 October 2011. Then Jibril announced that consultations were under way to form an interim government within one month, followed by elections for a constitutional assembly within eight months and parliamentary and presidential elections to be held within a year after that. He stepped down as expected the same day and was succeeded by Ali Tarhouni.

On 24 November, Tarhouni was replaced by Abdurrahim El-Keib. El-Keib formed a provisional government, filling it with independent or CNT politicians, including women.

After the fall of Gaddafi, Libya has been faced with internal struggles. A protest started against the new regime of NTC.[clarification needed] The loyalists of Gaddafi rebelled and fought with the new Libyan army.[clarification needed]

Because the Constitutional Declaration allowed a multi-party system, political parties, like theDemocratic Party, the Party of Reform and Development, and the National Gathering for Freedom, Justice and Development appeared. The Islamist movement started. To stop it, the CNT (NTC) government denied power to parties based on religion, tribal and ethnic bases.

On 7 July 2012, Libyans voted in their first parliamentary elections since the end of Gaddafi's rule. The election, in which more than 100 political parties registered, formed an interim 200-member national assembly. This will replace the unelected National Transitional Council,[94][95] name a prime minister, and form a committee to draft a constitution. The vote was postponed several times to resolve logistical and technical problems, and to give more time to register to vote, and to investigate candidates.[96]

On 8 August 2012, the National Transitional Council officially handed power to the wholly elected General National Congress, which is tasked with the formation of an interim government and the drafting of a new Libyan Constitution to be approved in a general referendum.[97]

On 25 August 2012, in what "appears to be the most blatant sectarian attack" since the end of the civil war, unnamed organized assailants bulldozed a Sufi mosque with graves, in broad daylight in the center of the Libyan capital Tripoli. It was the second such razing of a Sufi site in two days.[98]

On 7 October 2012, Libya's Prime Minister-elect Mustafa A.G. Abushagur stepped down[99] after failing a second time to win parliamentary approval for a new cabinet.[100][101] On 14 October 2012, the General National Congress elected former GNC member and human rights lawyer Ali Zeidan as prime minister-designate.[102]

Libyan Constitutional Assembly elections took place in Libya on 20 February 2014. Ali Zidan was ousted by the parliament committee and fled from Libya on 14 March 2014 after rogue oil tanker Morning Glory left the rebel port of Sidra, Libya with Libyan oil that had been confiscated by the rebels. Ali Zeidan had promised to stop the departure, but failed.[103][104]

On 30 March 2014 General National Congress voted to replace itself with new House of Representatives.[105]

Abdullah al-Thani served as the prime minister since 11 March 2014 in interim capacity. He resigned on 13 April 2014, after he and his family were victims of a "traitorous attack" but continued to remain prime minister since there was no replacement.[106] Ahmed Maiteeq was elected Prime Minister of Libya in May 2014 but his election as prime minister took place under disputed circumstances, Libyan Supreme Court ruled on 9 June that Maiteeq's appointment was illegal and Maiteeq resigned the same day.[107]

As of 18 May 2014[update], the parliament building was reported to have been stormed by troops loyal to General Khalifa Haftar,[108] reportedly including the Zintan Brigade,[109] in what the Libyan government described as an attempted coup.[110]

House of Representatives elections were held in Libya on 25 June 2014.

On 14 July, the United States Support Mission in Libya evacuated its staff after 13 people were killed in clashes in Tripoli and Benghazi. The fighting, between government forces and rival militia groups, also forced Tripoli International Airport to close. A militia, including members of the Libya Revolutionaries Operations Room (LROR), tried to seize control of the airport from the Zintan militia, which has controlled it since Gaddafi was toppled. Both militias are believed to be on the official payroll.[111][112] In addition Misrata Airport was closed, due to its dependence on Tripoli International Airport for its operations. Government spokesman, Ahmed Lamine, stated that approximately 90% of the planes stationed at Tripoli International Airport were destroyed or made inoperable in the attack, and that the government may make an appeal for international forces to assist in reestablishing security.[112]

In December 2015, the Libyan Political Agreement[113] was signed after talks in Skhirat, as the result of protracted negotiations between rival political camps based in Tripoli, Tobruk, and elsewhere which agreed to unite as the Government of National Accord (GNA). On 30 March 2016, Fayez Sarraj, the head of GNA, arrived in Tripoli and began working from there despite opposition from GNC.[114]

On 4 April 2019, Khalifa Haftar, the commander of the Libyan National Army, called on his military forces to advance on Tripoli, the capital of the internationally recognized government of Libya, in the 2019–20 Western Libya campaign[115] This was met with reproach from United Nations Secretary General António Guterres and the United Nations Security Council.[116][117]

On 23 October 2020, the 5+5 Joint Libyan Military Commission representing the Libyan National Army and the GNA reached a "permanent ceasefire agreement in all areas of Libya". The agreement, effective immediately, required that all foreign fighters leave Libya within three months while a joint police force would patrol disputed areas. The first commercial flight between Tripoli and Benghazi took place that same day.[118][119] On 10 March 2021, an interim unity government was formed, which was slated to remain in place until the next Libyan presidential election scheduled for 10 December.[120] However, the election has been delayed several times[121][122][123] since, effectively rendering the unity government in power indefinitely, causing tensions which threaten to reignite the war.

On September 10, 2023, catastrophic floods due to dam failures generated by Storm Daniel devastated the port city of Derna, killing nearly 7,000 and leaving over 10,000 missing. The floods were the worst natural disaster in Libya's modern history.[124]

See also

[edit]- Arab Spring

- History of North Africa

- History of the Jews in Libya

- List of heads of state of Libya

- Military history of Libya

- Politics of Libya

- Tripoli history and timeline

- Benghazi history and timeline

Notes

[edit]- ^ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Early History of Libya" Archived 22 September 2012 at archive.today, U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 July 2006.

- ^ St. John, Ronald Bruce (2017). Libya : From Colony to Revolution. Nathan St. John (3 ed.). London, England: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-78607-240-5. OCLC 988848424.

- ^ Oliver, Roland (1999), The African Experience: From Olduvai Gorge to the 21st Century (Series: History of Civilization), London: Phoenix Press, revised edition, pg 39.

- ^ Herodotus, (c.430 BCE), "'The Histories', Book IV.42–43" Archived 9 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Fordham University, New York. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ^ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Tripolitania and the Phoenicians" Archived 22 September 2012 at archive.today, U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 July 2006.

- ^ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, (1987), "Cyrenaica and the Greeks" Archived 22 September 2012 at archive.today, U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 11 July 2006.

- ^ History of Libya Archived 28 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The History Files. Retrieved 29 September 2011

- ^ a b c d e Bertarelli (1929), p. 202.

- ^ a b c d Bertarelli (1929), p. 417.

- ^ Bertarelli (1929), p. 382.

- ^ a b Rostovtzeff (1957), p. 364.

- ^ Cassius Dio, lxviii. 32

- ^ a b Rostovtzeff (1957), p. 335.

- ^ Heuser, Stephen, (24 July 2005), "When Romans lived in Libya" Archived 14 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Boston Globe. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ^ Tadeusz Lewicki, "Une langue romane oubliée de l'Afrique du Nord. Observations d'un arabisant", Rocznik Orient. XVII (1958), pp. 415–480.

- ^ a b Gibbon, Edward; Mueller, Hans-Friedrich (2005). The decline and fall of the Roman empire (Modern Library mass market ed.). New York: Modern Library. p. 1258. ISBN 0345478843. OCLC 58549764.

- ^ Rodd, Francis. "Kahena, Queen of the Berbers: A Sketch of the Arab Invasion of Ifrikiya in the First Century of the Hijra" Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 3, No. 4, (1925), 731–2

- ^ a b Bertarelli (1929), p. 278.

- ^ Hourani, Albert (2002). A History of the Arab Peoples. Faber & Faber. p. 198. ISBN 0-571-21591-2.

- ^ "Populations Crises and Population Cycles Archived 27 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine", Claire Russell and W.M.S. Russell.

- ^ a b c d e Bertarelli (1929), p. 203.

- ^ المؤلف : الطاهر أحمد الزاوي (28 March 2018). ولاة طرابلس من بداية الفتح العربي إلى نهاية العهد التركي.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip Chiviges (2009). North Africa: a history from antiquity to the present. University of Texas Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 9780292719224.

One of the most famous corsairs was Turghut (Dragut) (?–1565), who was of Greek ancestry and a protégé of Khayr al-Din. ... While pasha, he built up Tripoli and adorned it, making it one of the most impressive cities along the North African littoral.

- ^ a b c d e Bertarelli (1929), p. 204.

- ^ Robert C. Davis (5 December 2003). Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500–1800. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-71966-4. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Lisa Anderson, "Nineteenth-Century Reform in Ottoman Libya" Archived 10 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 16, No. 3. (August 1984), pp. 325–348.

- ^ a b Bertarelli (1929), p. 205.

- ^ Gökkent, Giyas Müeyyed (2021). Journey in the Grand Sahara of Africa and Through Time. Menah. ISBN 978-1-7371298-8-2.

- ^ Country Profiles, (16 May 2006), "Timeline: Libya, a chronology of key events" Archived 23 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine BBC News. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ^ Libya Archived 30 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Ilan Pappe, The Modern Middle East. Routledge, 2005, ISBN 0-415-21409-2, p. 26.

- ^ "Un patriota della Cirenaica". retedue.rsi.ch. 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ "Italian Tripoli". Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ Hagos, Tecola W., (20 November 2004), "Treaty Of Peace With Italy (1947), Evaluation And Conclusion" Archived 7 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Ethiopia Tecola Hagos. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ^ Chronology of International Events and Documents, Royal Institute of International Affairs. Vol. 7, No. 8 (5–18 April 1951), pp. 213–244

- ^ Holger Terp. "Fredsakademiet: Freds- og sikkerhedspolitisk Leksikon L 170 : Libya During the Cold War". Fredsakademiet.dk. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ Salak, Kira. "Rediscovering Libya". National Geographic Adventure. Archived from the original on 23 September 2011.

- ^ US Department of State's Background Notes, (November 2005) "Libya – History" Archived 4 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Dept. of State. Retrieved 14 July 2006.

- ^ a b c Mohamed Eljahmi (2006). "Libiya and the U.S.: Qadhafi Unrepentant". The Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Brian Lee Davis. Qaddafi, terrorism, and the origins of the U.S. attack on Libya.

- ^ The Middle East and North Africa 2003 (2002). Eur. p. 758

- ^ Wynne-Jones, Jonathan (19 March 2011). "Libyan minister claims Gaddafi is powerless and the ceasefire is 'solid'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ Eljahmi, Mohamed (2006). "Libya and the U.S.: Qadhafi Unrepentant". Middle East Quarterly. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Robbins, James (7 March 2007). "Eyewitness: Dialogue in the desert". BBC News. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ "Libya country update". European Forum. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011.

- ^ "Egypt Libya War 1977". Onwar.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ "Endgame in Tripoli". The Economist. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Geoffrey Leslie Simons. Libya: the struggle for survival. p. 281.

- ^ St. John, Ronald Bruce (1 December 1992). "Libyan terrorism: the case against Gaddafi". Contemporary Review. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "A Rogue Returns". AIJAC. February 2003. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011.

- ^ "African Countries by GDP Per Capita > GDP Per Capita (most recent) by Country". NationMaster. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ^ a b Azad, Sher (22 October 2011). "Gaddafi and the media". Daily News. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ "Zimbabwe: Reason Wafavarova – Reverence for Hatred of Democracy". AllAfrica.com. 21 July 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Shimatsu, Yoichi (21 October 2011). "Villain or Hero? Desert Lion Perishes, Leaving West Explosive Legacy". New America Media. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Bearman, Jonathan (1986). Qadhafi's Libya. London: Zed Books

- ^ "Gaddafi: Africa's 'king of kings'". BBC News. 29 August 2008. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ Schlamp, Hans-Jürgen (25 February 2011). "Kissing the Hand of the Dictator: What Libya's Troubles Mean for Its Italian Allies". Der Spiegel. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "A civil war beckons". The Economist. 3 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 February 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "The liberated east – Building a new Libya". The Economist. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ "Live Blog – Libya". Al Jazeera. 17 February 2011. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Saif al-Islam Gaddafi's defiant speech". The Daily Telegraph. London. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "Gaddafi's son warns of "rivers of blood" in Libya". Al Arabiya. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "Ex Libyan minister forms interim govt-report". LSE. 26 February 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya opposition launches council". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ "The Council"International Recognition". National Transitional Council (Libya). 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Libya: France recognises rebels as government". BBC News. 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Protesters march in Tripoli". Al Jazeera. 28 February 2011. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: France recognises rebels as government". BBC News. 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ The Guardian Live Blog Archived 22 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 10 March 2011

- ^ Fahim, Kareem; Kirkpatrick, David D. (9 March 2011). "Qaddafi Forces Batter Rebels in Strategic Refinery Town". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 May 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ The Independent, 9 March 2011 P.4

- ^ "Gaddafi vows to crush protesters". Al Jazeera. 25 February 2011. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Ban Ki-moon blasts Gaddafi; calls situation dangerous". Hindustan Times. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Some backbone at the U.N." Los Angeles Times. 26 February 2011. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Libya Expelled from UN Human Rights Council". Sofia News Agency. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "US slaps sanctions on Libyan govt". Al Jazeera. 26 February 2011. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Australia imposes sanctions on Libya". The Sydney Morning Herald. 27 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "Canada imposes additional Libyan sanctions". CBC News. 27 February 2011. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ "UN Security Council orders sanctions against Libya". Monsters & Critics. 27 February 2011. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "U.N. Security Council slaps sanctions on Libya". NBC News. 26 February 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

- ^ "Security Council authorizes 'all necessary measures' to protect civilians in Libya". United Nations News Service. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 3 May 2011. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ "Libya: Pro-Gaddafi forces 'to observe ceasefire'". BBC News. 18 March 2011. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ a b Jonathan Marcus (19 March 2011). "French military jets open fire in Libya". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ "Coalition launches Libya attacks". BBC. 19 March 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- ^ Ian Black and David Smith (27 June 2011). "War crimes court issues Gaddafi arrest warrant". The Guardian. Tripoli. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ a b Erdbrink, Thomas; Sly, Liz. "In Libya, Moammar Gaddafi's rule crumbling as rebels enter heart of Tripoli". The Washington Post.

- ^ Jennifer Welsh (20 September 2011). "Recognizing States and Governments–A Tricky Business". Canadian International Council. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (20 October 2011). "Qaddafi Is Dead, Libyan Officials Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ^ "Muammar Gaddafi killed as Sirte falls". Al Jazeera. 21 October 2011. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Vivienne Walt (19 October 2011). "In Tripoli, Libya's Interim Leader Says He Is Quitting". Time. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ "Libya Declares Liberation From 42-Year Gadhafi Rule". Voice of America. 2011. Archived from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Daragahi, Borzou (23 October 2011). "Libya declares liberation after Gaddafi's death". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ^ Karin Laub (8 September 2011). "Libyan estimate: At least 30,000 died in the war". The Guardian. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ Cousins, Michel (24 July 2012). "National Congress to meet on 8 August: NTC". Libya Herald. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "NTC to Transfer Power to Newly-Elected Libyan Assembly August 8". Tripoli Post. 2 August 2012. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "In Libya, Expectations High as Parliamentary Vote Approaches". PBS NewsHour. 5 July 2012. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Esam Mohamed (8 August 2012). "Libya's transitional rulers hand over power". Boston.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ "(Reuters by Yahoo News)". Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ George Grant (7 October 2012). "Congress dismisses Abushagur". Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ Sami Zaptia (7 October 2012). "Abushagur announces a smaller emergency cabinet". Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ "Libyan Prime Minister Mustafa Abu Shagur to stand down". BBC News. BBC. 7 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ^ "Libya Congress elects former congressman and rights lawyer Ali Zidan as new prime minister". The Washington Post. 14 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ David D Kirkpatrick (17 March 2014). "U.S. Navy SEALs Take Control of Diverted Oil Tanker". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ "Libya ex-PM Zeidan 'leaves country despite travel ban'". BBC. 12 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Congress votes to replace itself with new House of Representatives". Libya Herald. 30 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Frizell, Sam (13 April 2014). "Libya PM Quits, Says He Was Targeted in Armed Attack". Time. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ "Maetig accepts Supreme Court ruling and resigns". Libya Herald. 9 June 2014. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "Rogue General's Troops Storm Libyan Parliament". Sky News. 18 May 2014. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ "Gunfire erupts outside Libyan parliament". Al Jazeera. 18 May 2014. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ Fiona Keating (18 May 2014). "Libya: Rogue General Khalifa Haftar Storms Parliament in Attempted 'Coup'". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ Al-Warfalli, Ayman; Bosalum, Feras (14 July 2014). "U.N. pulls staff out of Libya as clashes kill 13, close airports". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ a b New rocket attack on Tripoli airport Archived 12 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News. 15 July 2014.

- ^ "UN welcomes 'historic' signing of Libyan Political Agreement". UN. 17 December 2015.

- ^ Stephen, Chris (30 March 2016). "Chief of Libya's new UN-backed government arrives in Tripoli". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (6 April 2019). "Libya: international community warns Haftar against Tripoli attack". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ "Libya army leader Khalifa Haftar orders forces to march on Tripoli". Los Angeles Times. 4 April 2019. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Mohareb, Hatem; Sarrar, Saleh; Al-Atrush, Samer (6 April 2019). "Libya Lurches Toward Battle for Capital as Haftar Advances". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Nebehay, Stephanie; McDowall, Angus (23 October 2020). Jones, Gareth; Maclean, William (eds.). "Warring Libya rivals sign truce but tough political talks ahead". Reuters. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "UN says Libya sides reach 'permanent ceasefire' deal". Al Jazeera. 23 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Libyan lawmakers approve gov't of PM-designate Dbeibah". Al Jazeera. 10 March 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ^ "Libya electoral commission dissolves poll committees". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ AfricaNews (17 January 2022). "UN: Libya elections could be held in June". Africanews. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "Libya's PM Dbeibah proposes holding polls at end of 2022". Daily Sabah. 26 May 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ Elumami, Ahmed; Al-Warfali, Ayman; Alfetori, Essam (14 September 2023). "Libya floods: search for blame for thousands of deaths". Reuters.

Bibliography

[edit]- St John, Ronald Bruce (2006). Historical dictionary of Libya. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-5303-5.

- Chapin Metz, Helen, ed. (1987). Libya: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress.

- Nelson, Harold D.; Nyrop, Richard F. (1987). Libya: A Country Study. Library of Congress Country Studies. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. OCLC 5676518.

- Wright, John L. (1969). Nations of the Modern World: Libya. Ernest Benn Ltd.

- Bertarelli, L.V. (1929). Guida d'Italia (in Italian). Vol. XVII. Milano: Consociazione Turistica Italiana.

- Tuccimei, Ercole (1999). La Banca d'Italia in Africa, Foreword by Arnaldo Mauri, Laterza, Bari.

- Pierre Schill, Réveiller l’archive d’une guerre coloniale. Photographies et écrits de Gaston Chérau, correspondant de guerre lors du conflit italo-turc pour la Libye (1911–1912), Créaphis, 2018, 480 pages and 230 photographs. ISBN 978-2-35428-141-0.[1]

External links

[edit]- History of Libya | Libya Connected (archived 20 April 2007)

- Libya in Crisis: Modern History of Libya (archived 17 March 2013) from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives