Incarceration: Difference between revisions

Cdogsimmons (talk | contribs) Undid revision 395272204 by JJAlexander (talk) |

JJAlexander (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

Within the framework of [[penology]], the trend toward increasing the severity of punishments is reflected in publications such as Block's (1997, p. 12) advocacy of policy initiatives aimed at increasing the unpleasantness of prison life that would likely be ''"a cost-effective method of fighting crime”'' and [[Joseph Arpaio|Arpaio]] and Sherman's 1996 book claiming that the increase in the severity of treatment of prisoners will result in decrease in [[recidivism]].<ref>The opinion that increasing the severity of punishments will result in decrease of recidivism is not supported by some metastudies of this issue. Contrary to this popular opinion, the majority of research studies indicates that penal policies stressing rehabilitation over punishment result in lower recidivism rates. Most empirical studies consistently find that the employment status after the release from prison is the strongest predictor of recidivism. Thus, e.g., ''Pennsylvania's 2000 Legislative Report on Recidivism'' concludes that ''"most studies found that boot camps have not been very successful in achieving the goal of reducing crime"'' and that the fact that ''"employed offenders are almost three times as likely to succeed indicates that providing vocational training and employment opportunities for offenders should be a high priority."''</ref> Arpaio and Sherman proposed to increase the severity of imprisonment by the construction of tent prison camps in the [[Mojave Desert]] where summer temperatures reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit, by serving prisoners foul-tasting food, by humiliating prisoners by cross-dressing, and by reinstatement of the [[chain gang]]s. Mauer (1999, pp. 92–93) documents some other the measures used to implement the ''increasing the unpleasantness of prison life'' policies that include shooting around prisoners to keep them moving, forced consumption of milk of magnesia, placing naked inmates in ''strip cells,'' and handcuffing inmates for long periods of time. |

Within the framework of [[penology]], the trend toward increasing the severity of punishments is reflected in publications such as Block's (1997, p. 12) advocacy of policy initiatives aimed at increasing the unpleasantness of prison life that would likely be ''"a cost-effective method of fighting crime”'' and [[Joseph Arpaio|Arpaio]] and Sherman's 1996 book claiming that the increase in the severity of treatment of prisoners will result in decrease in [[recidivism]].<ref>The opinion that increasing the severity of punishments will result in decrease of recidivism is not supported by some metastudies of this issue. Contrary to this popular opinion, the majority of research studies indicates that penal policies stressing rehabilitation over punishment result in lower recidivism rates. Most empirical studies consistently find that the employment status after the release from prison is the strongest predictor of recidivism. Thus, e.g., ''Pennsylvania's 2000 Legislative Report on Recidivism'' concludes that ''"most studies found that boot camps have not been very successful in achieving the goal of reducing crime"'' and that the fact that ''"employed offenders are almost three times as likely to succeed indicates that providing vocational training and employment opportunities for offenders should be a high priority."''</ref> Arpaio and Sherman proposed to increase the severity of imprisonment by the construction of tent prison camps in the [[Mojave Desert]] where summer temperatures reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit, by serving prisoners foul-tasting food, by humiliating prisoners by cross-dressing, and by reinstatement of the [[chain gang]]s. Mauer (1999, pp. 92–93) documents some other the measures used to implement the ''increasing the unpleasantness of prison life'' policies that include shooting around prisoners to keep them moving, forced consumption of milk of magnesia, placing naked inmates in ''strip cells,'' and handcuffing inmates for long periods of time. |

||

=== Biblical Perspective on Incarceration === |

|||

The Bible places restitution in the center for Justice, not confinement. For theft, rape, murder, kidnapping, and any other assault on mankind and the societal order, restitution, not confinement, was required to make right the wrong. Besides restitution, capital punishment was executed against murderers, kidnappers and others found guilty of actions that violated Biblical moral or ethical code. |

|||

It must be observed that the punishments the Bible described were delivered in the form of a Covenant. God laid down the terms, and His people - the Israelites - agreed to live by these terms. They voluntarily agreed to be hold to them, and accept and execute the prescribed punishments for violations. |

|||

=== Incarceration and torture === |

=== Incarceration and torture === |

||

Revision as of 01:45, 7 November 2010

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. |

Incarceration is the detention of a person in jail, typically as punishment for a crime. People are most commonly incarcerated upon suspicion or conviction of committing a crime, and different jurisdictions have differing laws governing the function of incarceration within an larger system of justice. Incarceration serves four essential purposes with regard to criminals:

- to punish criminals for committing crimes

- to isolate criminals to prevent them from committing more crimes

- to deter others from committing crimes

- to rehabilitate criminals

Incarceration rates, when measured by the United Nations, are considered distinct and separate from the imprisonment of political prisoners and others not charged with a specific crime. Historically, the frequency of imprisonment, its duration, and severity have varied considerably. There has also been much debate about the motives for incarceration, its effectiveness and fairness, as well as debate regarding the related questions about the nature and etiology of criminal behavior.

Justice studies

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2008) |

Wilkenson (2004) notes that overall heterogeneity of a society may provide a meta-explanation for the variance in incarceration rates: There may be a multi-directional causality where close-knit societies are least likely to offend against one another. Knowing ones' neighbors may hence bridge econometric explanations across communities. Or put another way, except perhaps for crimes of passion, people do not offend against people they know well.

Penology and justice studies emphasize description and analysis of antecedents of criminal behavior and outcomes of consequences imposed by criminal justice on the criminal behavior. An example of a modern quantitative study of factors influencing the criminal behavior is the study by Krus and Hoehl (1994).

In the study by Krus and Hoehl, variables that might explain differences in incarceration rates among populations were located by a computer-aided search of the compendium of world rankings, compiled by the Facts on File Corporation and the World Model Group, containing over 50,000 records on more than 200 countries.

They argued that predictor variables explained about 69% of variance in the international incarceration rates. Cited as especially important were unequal distribution of wealth (the explanation perhaps favored by liberals) and family disintegration (the explanation perhaps favored by conservatives). According to Krus and Hoehl, these variables act in concert: the presence of one variable does not always precipitate crime, but the presence of both variables often does precipitate crime.

Incarceration rates by country

In many countries, it is common for prisoners to be paroled after serving as little as one third of their sentences.

China

In 2001 the incarceration rate in China was 111 per 100,000 in 2001 (sentenced prisoners only), although this figure is highly disputed. Chinese human rights activist Harry Wu, now an American citizen, who spent 19 years in forced-labor camps for criticizing the government, alleging that 16 to 20 million of his countrymen are incarcerated, including common criminals, political prisoners, and people in involuntary job placements. Even ten million prisoners would mean a rate of 793 per 100,000.[5]

Involuntary job placement is where the education system decides what vocational training or college major you will get, according to your aptitudes and availability of classroom seats. This was standard practice at least until 1978.

Denmark

Denmark also has a low incarceration rate with a total of 3774 inmates in the country.[6] Denmark has 59 people in prison for every 100,000 citizens.[6] 62 violent crimes such as rape, murder, robbery, and aggravated assault were reported. There were 322 Property Crimes reported.

England and Wales

In 2006 the incarceration rate in England and Wales is 139 persons imprisoned per 100,000 residents, while in Norway it is 59 inmates per 100,000, whilst the Australian imprisonment rate is 163 prisoners per 100,000 residents, and the rate of imprisonment in New Zealand last year was 179 per 100,000.

India

India has one of the lowest incarceration rates with only 281,000 prisoners in their jails.[6] This is just a fraction of their total population, 1,129,866,154.[6] India reported 1,764,630 crimes in 2007.[6] There were 236,313 assaults and 111,296 burglaries.[7]

United States

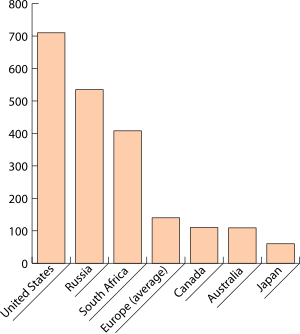

The United States' incarceration rate is, according to official reports, the highest in the world, at 737 persons imprisoned per 100,000 (as of 2005).[8] A report released in 2008 indicates that in the United States more than 1 in 100 adults is now confined in an American jail or prison.[9] The United States has 4% of the world's population and 25% of the world's incarcerated population.[10]

In the U.S., most states strictly limit parole, requiring that at least half of a sentence be served. For certain heinous crimes, there is no parole and the full sentence must be served.

Conditions of incarceration

Severe punishments (such as beatings, prolonged sleep deprivation, sensory deprivation, chaining) have been often inflicted on prisoners. There are many reasons given for justification of such punishment. In the 16th century, the Bishop of Trier, Binsfeld, in his Tractatus de Confessionibus Maleficorum (1596) claimed that

- since the sinfulness of the world increases, God also allows increasing the severity of punishments.

A movement to abolish cruel treatment of prisoners began during the Age of Enlightenment and continued throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. However, there have been continual arguments for severe punishments, perhaps increasing somewhat in the early years of the 21st century. Contemporary justifications for such punishment often revolve around the "rights of the victims". Often underlying these perspectives are opinions that stress the vindictive eye-for-the-eye notions of the Old Testament and Qur'an [11], over the notion that the primary goal of incarceration should be the reform and reeducation of prisoners to facilitate their re-integration into society.

Within the framework of penology, the trend toward increasing the severity of punishments is reflected in publications such as Block's (1997, p. 12) advocacy of policy initiatives aimed at increasing the unpleasantness of prison life that would likely be "a cost-effective method of fighting crime” and Arpaio and Sherman's 1996 book claiming that the increase in the severity of treatment of prisoners will result in decrease in recidivism.[12] Arpaio and Sherman proposed to increase the severity of imprisonment by the construction of tent prison camps in the Mojave Desert where summer temperatures reach 120 degrees Fahrenheit, by serving prisoners foul-tasting food, by humiliating prisoners by cross-dressing, and by reinstatement of the chain gangs. Mauer (1999, pp. 92–93) documents some other the measures used to implement the increasing the unpleasantness of prison life policies that include shooting around prisoners to keep them moving, forced consumption of milk of magnesia, placing naked inmates in strip cells, and handcuffing inmates for long periods of time.

Biblical Perspective on Incarceration

The Bible places restitution in the center for Justice, not confinement. For theft, rape, murder, kidnapping, and any other assault on mankind and the societal order, restitution, not confinement, was required to make right the wrong. Besides restitution, capital punishment was executed against murderers, kidnappers and others found guilty of actions that violated Biblical moral or ethical code.

It must be observed that the punishments the Bible described were delivered in the form of a Covenant. God laid down the terms, and His people - the Israelites - agreed to live by these terms. They voluntarily agreed to be hold to them, and accept and execute the prescribed punishments for violations.

Incarceration and torture

As noted above, cruel treatment has long been a feature of incarceration. Taken to extremes, such treatment might be described as torture.

Torture has, for much of history, been seen as a tolerable or even necessary component of imprisonment, whether performed as punishment or as part of interrogation.[citation needed] Recent controversial cases described by critics as torture of incarcerated people include the Abu Ghraib military prison in Iraq and the Guantanamo Bay, Cuba scandal.

See also

- List of countries by incarceration rate

- Detention (imprisonment)

- Sentencing Project

- Supreme crime

- Recidivism

- Incapacitation (penology)

Notes

- ^ Human Development Report 2007/2008 - Prison population (per 100,000 people). United Nations Development Programme.

- ^ World Prison Population List. 7th edition. By Roy Walmsley. Published in 2007. International Centre for Prison Studies. School of Law, King's College London. For editions 1 through 7: [1].

- ^ World Prison Brief - Highest to Lowest Figures. International Centre for Prison Studies. School of Law, King's College London. Compare many nations. Select from menu: prison population total, prison population rate, percentage of pre-trial detainees / remand prisoners within the prison population, percentage of female prisoners within the prison population, percentage of foreign prisoners within the prison population and occupancy rate.

- ^ Human Development Report 2007/2008 - Prison population (per 100,000 people). UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), using data from the World Prison Population List.

- ^ This sentence is copied verbatim from http://www.straightdope.com/columns/040206.html

- ^ a b c d e World Prison Population List by Roy Walmsley-http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs2/r188.pdf

- ^ NationMaster - Indian Crime statistics

- ^ Paige M. Harrison and Allen J. Beck, Ph.D. (November 2006). "Prisoners in 2005" (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. p. 13.

- ^ One in 100: Behand Bars in America

- ^ http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs2/r188.pdf

- ^ Aslam Abdullah (2006, http://www.beliefnet.com ) in Demystifying Muslim Justice observes that " most Americans' impression of Islamic justice is a rather barbaric image of retribution harshly and violently administered. Ask even educated Americans to explain the law in Muslim countries, and they'll inevitably talk about hands and heads summarily being severed. In fact, Islamic justice shares much with Christianity and Judaism. These similarities are not surprising, considering that our penal systems are influenced by common scriptural foundations. The Qur'an's most basic passage pertaining to punishment is a familiar one to Christians and Jews alike: "And We prescribed for them therein: The life for the life, and the eye for the eye, and the nose for the nose, and the ear for the ear, and the tooth for the tooth, and for wounds equality." That said, even in Talmudic times, this was never intended for Jews to be taken literally, and has always been interpreted by the Rabbis to indicate that appropriate compensation be paid in the form of money.

- ^ The opinion that increasing the severity of punishments will result in decrease of recidivism is not supported by some metastudies of this issue. Contrary to this popular opinion, the majority of research studies indicates that penal policies stressing rehabilitation over punishment result in lower recidivism rates. Most empirical studies consistently find that the employment status after the release from prison is the strongest predictor of recidivism. Thus, e.g., Pennsylvania's 2000 Legislative Report on Recidivism concludes that "most studies found that boot camps have not been very successful in achieving the goal of reducing crime" and that the fact that "employed offenders are almost three times as likely to succeed indicates that providing vocational training and employment opportunities for offenders should be a high priority."

References

- ABC News/Washington Post poll (2004). Conducted by TNS of Horsham, Pa, on a random national sample of 1,005 adults with a three-point error margin.

- Arpaio, J. and Sherman, L. (1996) How to win the war against crime. Arlington: The Summit Publishing Group.

- Binsfeld, P. (1596) Tractatus de confessionibus maleficorum et sagarum. Trier, Germany: Heinrich Bock.

- Block, M. K. (1997) Supply side imprisonment policy. Washington: National Institute of Justice.

- Beccaria, C. (1764) An essay on crimes and punishments. New York: Gould & Van Winkle, 1809.

- Daneau, L. (1564) Les Sorciers, dialogue très utile et très necessaire pour ce temps. In Levack, B. (1992) The literature of witchcraft: articles on witchcraft, magic, and demonology. Garland. ISBN 0-8153-1026-9.

- Geiler, J. (1508) Die Emeis. Strassburg: Johann Grüninger.

- Kurian, G.T. (1991) The New Book of World Rankings. New York: Facts on File, Inc.

- Krus, D.J. (1999) Die Harte des Strafvollzugs: Entbindung in Ketten. Zeitschrift fur Sozialpsychologie und Gruppendynamik in Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, 24Jg/Heft 4, S.12-16 (Request reprint in English,in German).

- Krus, D. J., & Hoehl, L .S. (1994) Issues associated with international incarceration rates. Psychological Reports, 75, 1491-1495 (Request reprint).

- Mauer, M. (1991) American Behind Bars: A Comparison of International Rates of Incarceration. Washington, D.C.: The Sentencing Project.

- Mauer, M. (1999) Race to incarcerate. New York: The New Press.

- Mǖllendorf, P. (1911) Geschichte der Spanischen Inquisition. Leipzig, Germany.

- Rhyne, C. E., Templer, D. I., Brown, L. G., & Peters, N. B. (1995) Dimensions of suicide: perceptions of lethality, time, and agony. Suicide & Life Threatening Behavior, 25(3), 373-380.

- Sindelar, B. (1986) Hon na carodejnice v zapadni a stredni Evrope v 16.-17.stoleti. Prague: Nakladatelstvi Svoboda.

External links

- Race and Incarceration in the United States. Human Rights Watch Press Backgrounder. February 27, 2002. Many tables.

- Red Magazine, stories about prisoners and prison conditions