Dookie

| Dookie | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | February 1, 1994 | |||

| Recorded | September–October 1993 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 39:35 | |||

| Label | Reprise | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Green Day chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Dookie | ||||

| ||||

Dookie is the third studio album by the American rock band Green Day, released on February 1, 1994, by Reprise Records. The band's major label debut and first collaboration with producer Rob Cavallo, it was recorded in late summer 1993 at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, California. Written mostly by the singer and guitarist Billie Joe Armstrong, the album is largely based on his personal experiences and includes themes such as boredom, anxiety, relationships, and sexuality. It was promoted with four singles: "Longview", "Basket Case", a re-recorded version of "Welcome to Paradise" (which originally appeared on the band's second studio album, 1991's Kerplunk), and "When I Come Around".

After several years of grunge's dominance in popular music, Dookie brought a livelier, more melodic rock sound to the mainstream and propelled Green Day to worldwide fame. Considered one of the defining albums of the 1990s and of punk rock in general, it was also pivotal in solidifying the genre's mainstream popularity. Its influence continued into the new millennium and beyond, being cited as an inspiration by many punk rock and pop-punk bands, as well as artists from other genres.

Dookie received critical acclaim upon its release, although some early fans accused the band of being sellouts for leaving its independent label (Lookout! Records) and embracing a more polished sound. The record won a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Album at the 37th Annual Grammy Awards in 1995. It was a worldwide success, peaking at number two on the Billboard 200 in the United States and reaching top ten positions in several other countries. Dookie was later certified double diamond (20-times platinum) by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). It has sold over 20 million copies worldwide, making it the band's best-selling album and one of the best-selling albums of all time. It has been labeled by critics and journalists as one of the greatest albums of the 1990s and one of the greatest punk rock and pop-punk albums of all time. Rolling Stone placed Dookie on all four iterations of its "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time" list,[1] and at number 1 on its "The 50 Greatest Pop-Punk Albums" list in 2017.[2] In 2024, the album was selected for preservation in the United States National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[3]

Background

[edit]

With the success in the independent world of the band's first two albums, 39/Smooth (1990) and Kerplunk (1991), which sold 30,000 units each,[4][5] a number of major record labels became interested in Green Day.[6] Among those labels were Sony, Warner Bros., Geffen and Interscope.[4][5] Representatives of these labels attempted to entice the band to sign by inviting them for meals to discuss a deal, with one manager even inviting the group to Disneyland.[7] The band declined these advances; Armstrong believed that the labels were more than likely looking for something that resembled a grunge band, namely "second- and third-rate Nirvanas and Soundgardens",[8] and they did not want to conform to a label's vision. That changed when they met the producer and A&R representative Rob Cavallo of Reprise, a subsidiary of Warner Bros.[5][9] The band played Beatles covers for him for 40 minutes, then Cavallo picked up his own guitar and jammed with them.[9][10] They were impressed by his work with fellow Californian band the Muffs, and later remarked that Cavallo "was the only person we could really talk to and connect with".[7]

Eventually, the band left their independent record label, Lookout! Records, on friendly terms. They signed a five-album deal with Reprise in April 1993. The deal secured Cavallo as the producer of the first record and allowed the band to retain the rights to its albums on Lookout!. [11][12][9] Signing to a major label caused many of Green Day's original fans to label them sell-outs, including the influential punk fanzine Maximumrocknroll[9][10] and the independent music club 924 Gilman Street.[13][14] After Green Day's September 3 gig at 924 Gilman Street,[15] the venue banned the group from entering or playing.[7][16] Reflecting back on the period, the singer and guitarist, Billie Joe Armstrong, told Spin magazine in 1999, "I couldn't go back to the punk scene, whether we were the biggest success in the world or the biggest failure [...] The only thing I could do was get on my bike and go forward."[17] The group later returned in 2015 to play a benefit concert.[18]

Recording

[edit]

Following the band's last Gilman Street performance, Green Day demoed the songs "She", "Sassafras Roots", "Pulling Teeth" and "F.O.D." on Armstrong's four-track tape recorder and sent it to Cavallo. After listening to it, Cavallo sensed that "[he] had stumbled on something big."[6][8] However, he recognized that the band members were struggling to play their best; he reasoned that they were anxious because the most time they had previously spent recording an album was three days while recording Kerplunk. To lighten the mood, he invited them to a Mexican restaurant and bar down the street from Fantasy Studios, even though the drummer Tré Cool was not of legal drinking age at the time.[19] Armstrong confirmed the band's anxiety in an interview years later, describing the group feeling "like little kids in a candy store" and fearing that the band would lose money on work being scrapped by the label for not meeting standards. Despite this, they focused on making the most of the new production resources at their disposal; unlike their previous albums where the band had to rush to complete them to save money, the band took their time to perfect the quality of their output. Armstrong noted that he learned "how to dial in good sounds, get the best guitar tones. I was able to take a little time doing vocals."[8]

Recording took place over the course of three weeks at Fantasy, and the album was mixed twice by Cavallo and the producer Jerry Finn.[7][19] Though the band took their time to make a quality product as a whole, Armstrong's vocals were still recorded very quickly; he recorded about 16 or 17 songs in two days, most of them in a single take.[20][21] Armstrong said the band at first "wanted it to sound really dry, the same way the Sex Pistols record or the early Black Sabbath records sounded",[22] but the band found the result of this approach to be an unsatisfactory original mix. Cavallo agreed, and it was remixed at Devonshire Sound Studios in North Hollywood, Los Angeles.[23] During the remixing process, the band took to Music Grinder Studio in Los Angeles to re-record the tracks "Chump" and "Longview" as the original recordings had been "plagued by an inordinate amount of tape hiss".[23] Armstrong later said of their studio experience, "Everything was already written, all we had to do was play it."[7][22] Among the material recorded but not included on the album was "Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)", which would later be re-recorded for the band's 1997 album Nimrod and become a hit in its own right.[24] The band also recorded new versions of the songs "Welcome to Paradise", "2000 Light Years Away"[23] and "Christie Rd." from their second album Kerplunk and "409 in Your Coffeemaker" from their second EP Slappy, though only "Welcome to Paradise" would make it onto the final album.[25]

Writing and composition

[edit]Much of Dookie's content was written by Armstrong, except "Emenius Sleepus", which was written by the bassist Mike Dirnt, and the hidden track, "All by Myself", which was written by Tré Cool. The album touched upon various experiences of the band members and included subjects such as anxiety and panic attacks, masturbation, sexual orientation, boredom, mass murder, divorce, domestic abuse, and ex-girlfriends.[7] PopMatters summarized the album's theme as "a record that speaks of the frustrations, anxieties, and apathy of young people".[26] Stylistically, the album has been categorized primarily as punk rock,[27][28][29] but also as pop-punk[26][30][31] and as a "power pop take" on skate punk.[32] Influences from the Ramones and the Sex Pistols were noted in Armstrong's guitar technique throughout the album; he recorded the album almost entirely with his Fernandes Stratocaster, which he named "Blue".[31]

Songs 1–7

[edit]Dookie opens with "Burnout", a "speedy, antsy rocker" centered around a central character's feelings of general apathy toward life.[26] Armstrong wrote the song "Having a Blast" when he was in Cleveland in June 1992.[33] The song revolves around a mentally ill character who plans to use explosives to kill himself and others. This was not regarded as a serious issue at the time, as the social climate could allow the song to be viewed as "mere cathartic fantasy", but later incidents such as the 1999 Columbine High School massacre have made the song the "most uncomfortable track" on the album.[34] On "Chump", Armstrong takes the perspective of someone who shows prejudice, insulting another person without actually knowing them. At the end of the song, it is revealed that the disliked person in question matches Armstrong's description of himself.[35] "Chump" is also the first of three songs that allude to Amanda, a former girlfriend of Armstrong's.[22] The album's first single, "Longview", had a signature bass line that Dirnt wrote while under the influence of LSD.[36] In an interview with Guitar World in 2002, Armstrong described the character in the song as based on himself when he lived in Rodeo, California: "There was nothing to do there, and it was a real boring place."[37] To entertain himself, the character does nothing but watch television, smoke marijuana, and masturbate, and has little motivation to change these habits despite tiring of the same cycle of behaviors.[37]

"Welcome to Paradise", the third single from Dookie, originally appeared on the band's second studio album, Kerplunk!. The song was written about Armstrong's experiences living in bad neighborhoods around Oakland, California.[38] "Pulling Teeth", one of the album's slower songs, uses dark humor about domestic violence. The typical victim and perpetrator are reversed; the male narrator is at the mercy of his female partner.[24] The band's inspiration for this song came from a pillow fight between Dirnt and his girlfriend that ended with the bassist breaking his elbow.[39][40] The second single, "Basket Case", which appeared on many singles charts worldwide,[41][42] was also inspired by Armstrong's personal experiences. The song deals with Armstrong's anxiety attacks and feelings of "going crazy" before being diagnosed with a panic disorder.[22] Using a palm mute, Armstrong is the only one who plays on the song until halfway through the song's first chorus, with the other instruments' arrival representing panic setting in.[43] In the third verse, "Basket Case" mentions soliciting a male prostitute; Armstrong said, "I wanted to challenge myself and whoever the listener might be. It's also looking at the world and saying, 'It's not as black and white as you think. This isn't your grandfather's prostitute – or maybe it was.'"[8] The music video was filmed in an abandoned mental institution. It is one of the band's most popular songs.[44]

Songs 8–14

[edit]"She" was written about Amanda, who showed him a feminist poem entitled "She".[22] In return, Armstrong wrote the lyrics of "She" and showed them to her.[22] When Amanda broke up with Armstrong in early 1994 and moved to Ecuador to join the Peace Corps, Armstrong decided to put "She" on the album.[45] Musically, "She" is similar to "Basket Case", although it is slightly faster, and draws inspiration from the Beatles. The song's beginnings mirror those of "Basket Case"; whereas Armstrong was the only one to play as "Basket Case" began, Armstrong's guitar does not enter until later in "She" while his bandmates provide a musical backdrop. The song tells the story of a young woman who feels trapped in an unsatisfactory life.[40][46] Amanda is also referenced in the next track, "Sassafras Roots".[22] Sonically closer to the band's material on Kerplunk!,[40] it is an unconventional love song that uses irony and sarcasm in an effort to avoid being direct, and centers on a couple wasting time together in a romantic relationship.[47] The tenth track, "When I Come Around", was the album's final single. It was inspired by Adrienne Nesser, Armstrong's girlfriend and eventual wife. Following a dispute between the couple, Armstrong left Nesser to spend some time alone.[6] Described as the closest thing to a ballad on the album,[40] "When I Come Around" is driven by a recognizable two-bar, palm-muted guitar riff of four chords, while Dirnt's bass part stands out by adding additional pulled-off and hammered-on portions to the guitar's accompaniment. The song's lyrics highlight two meanings of its title: the narrator begins by talking to someone they believe they could address the needs of, having literally come around; in the second verse, the singer realizes they aren't what the other person needs, having "come around" figuratively.[48]

The song "Coming Clean" deals with Armstrong's coming to terms with his bisexuality as a teenager. At the time, he was still looking for himself sexually and had no well-defined sexual orientation.[24] In his interview with The Advocate magazine, he said that although he has never had a relationship with a man, his sexuality has been "something that comes up as a struggle in me".[49] "Emenius Sleepus", written by Dirnt, is about two old friends who meet by chance, and the narrator realizes that they have both changed a lot as people.[24] Played in a quick staccato-styled rhythm,[50] Armstrong wrote the song "In the End" about his mother and stepfather, and the reproach Armstrong felt toward his mother for choosing his stepfather as a partner.[24] "F.O.D.", an acronym for "Fuck Off and Die", begins calmly with Armstrong alone on acoustic guitar, before the band suddenly arrives in a louder, full-force fashion. The theme of the song centers around the singer's grudge for another individual, and wishing misfortune upon them.[51] A hidden track, "All By Myself", with vocals and guitar by Cool, plays after "F.O.D." ends, and is about masturbation.[52]

Packaging

[edit]

Dookie is American slang for feces. It is a reference to the diarrhea—"liquid dookie"—that the band members suffered while eating spoiled food on tour. Initially, the band aimed to name the album Liquid Dookie, but this was shortened to Dookie.[22] Asked in 2014 if the choice was a mistake in hindsight, Armstrong said it had been an impulsive "stoner thing": "We were smoking a lot of weed [and said] 'Hey, man, wouldn't it be funny if...'"[8]

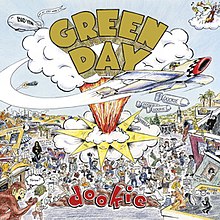

For its cover art, the band commissioned artist Richie Bucher, who created a cartoon-like work depicting bombs being dropped on people and buildings. Bucher says Armstrong only told him the album's title, so he worked around the theme of fecal matter. As a child, Bucher had associated feces with dogs and monkeys, both of which appear prominently on the album's cover.[19]

The setting is a replica of Berkeley's Telegraph Avenue. In the center, there is an explosion with the band's name at the top.[53] The cover depicts Patti Smith showing off her armpit as shown on the cover of her album Easter (1977), a shootout surrounding Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton, the woman on Black Sabbath's self-titled debut album, Angus Young of AC/DC, and the Sather Tower. Friends of the band members are among the foreground figures on whom dogs and monkeys throw their excrement. A dog pilots the plane that drops bombs with the words Dookie written on them, while the name of the group is written in brown in the center of the explosion. Oil refineries in Rodeo, California, can be seen in the distance.[54][19][8]

Armstrong has since explained the meaning of the artwork:

I wanted the art work to look really different. I wanted it to represent the East Bay and where we come from, because there's a lot of artists in the East Bay scene that are just as important as the music. So we talked to Richie Bucher. He did a 7-inch cover for this band called Raooul that I really liked. He's also been playing in bands in the East Bay for years. There's pieces of us buried on the album cover. There's one guy with his camera up in the air taking a picture with a beard. He took pictures of bands every weekend at Gilman's. The robed character that looks like the Mona Lisa is the woman on the cover of the first Black Sabbath album. AC/DC guitarist Angus Young is in there somewhere too. The graffiti reading "Twisted Dog Sisters" refers to these two girls from Berkeley. I think the guy saying "The fritter, fat boy" was a reference to a local cop.[6]

When the trio went to Warner's offices in Los Angeles to discuss marketing for the album, label officials initially wanted the cover to feature a photograph of the comely young men, but the band refused. George Weiss, Warner's marketing director, noted that the band came from a distinctly different culture than most of their artists, and Green Day had gained the leverage with the label to insist on a different choice.[19] The back cover on early prints of the CD featured a plush toy of Ernie from Sesame Street, which was airbrushed out of later prints for fear of litigation;[54] however, Canadian and European prints still feature Ernie on the back cover.[7] Some rumors suggest that it was removed because it led parents to think that Dookie was a child's lullaby album or that the creators of Sesame Street had sued Green Day.[6]

Release

[edit]While rehearsing in the house they rented in Berkeley at the end of 1993 in anticipation of a tour for Dookie,[19] the band was invited to the Warner offices in Los Angeles to discuss the marketing strategy around the album with Weiss. The latter expected to meet three scornful young men with reputations in punk music, when in reality the band members were intimidated to even be invited to the meeting. They discussed the first single, "Longview", as well as projected goals for the album's sales: Cavallo hoped to sell at least 200,000 units, while Cool looked higher toward 500,000.[55] Demand was well underestimated; when Dookie was released on February 1, 1994, the album's first 9,000 produced copies quickly sold out.[54][56] "Longview" was released as the album's lead single simultaneously with the album.[57] Despite promising demand from the quick depletion of the album's initial supply, it initially resulted in modest total sales as strategies were adjusted to meet demand, and only after the music video for "Longview" debuted on MTV on February 22 did the album begin to attract stronger attention, first entering the Billboard 200 rankings at number 127.[54]

In March, the group made appearances on Late Night with Conan O'Brien, The Jon Stewart Show and 120 Minutes on MTV.[54][58] Sales for Dookie rose greatly following these performances, peaking at number two on the Billboard 200 in the United States.[59] The record became an international success as well; the album peaked in the top ten of the German,[60] Finnish,[61] Norwegian,[62] Dutch,[63] Italian,[64] Swedish,[65] and Swiss[66] charts, while it topped the Australian,[67] Canadian,[68] and New Zealand charts.[69] By June 14, Dookie was certified gold by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), having sold more than 500,000 copies in the United States.[70] That month, an issue of Time hailed the album as a work creating an impact comparable to Nirvana's Nevermind (1991).[58]

On August 1, "Basket Case" was released as the album's second single.[71] The song's music video quickly became an MTV staple.[72][58] The following month, "Longview" was nominated in three categories at the 1994 MTV Video Music Awards. Green Day performed the unreleased song "Armatage Shanks" at the ceremony, which would later appear on their following album Insomniac (1995), but did not win any of the categories which they were nominated for.[73][74] In October, Warner proposed "Welcome to Paradise" to be the third single, noting potential to make good sales. However, Armstrong refused because the song evoked a part of his life and he did not feel capable of promoting it with a music video. The song was ultimately only broadcast on the radio domestically, being met with great success despite not being sold to the public.[75] An exclusive United Kingdom single release for the song did proceed on October 17.[76] Near the end of 1994, Don Pardo invited the band to perform on Saturday Night Live.[58]

Ahead of the 37th Annual Grammy Awards, "When I Come Around" was released to radio as the album's final single in December 1994.[77] The band had been nominated in four Grammy Award categories: Best Alternative Music Album, Best New Artist, Best Rock Performance by a Duo or Group with Vocal with "Basket Case", and Best Hard Rock Performance with "Longview". They won only the former of the categories.[78] In the meantime, "When I Come Around" had been quickly climbing the charts; it held the top of the Billboard Modern Rock Chart for seven weeks and peaked at number six of the Hot 100 Airplay chart,[79][80] becoming the band's most successful single from the album.[48] Throughout the 1990s, Dookie continued to sell well, eventually receiving diamond certification from the RIAA in 1999, signifying ten million copies sold.[70] By 2014, Dookie had sold over 20 million copies worldwide and remains the band's best-selling album.[81][82] By 2024, the RIAA had certified it 20× platinum — double diamond — for twenty million copies sold in the United States alone.[70]

Reception

[edit]| Initial reviews (in 1994/1995) | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Chicago Sun-Times | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Select | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 8/10[86] |

| The Village Voice | A−[87] |

| Retrospective reviews (after 1994/1995) | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Alternative Press | |

| Billboard | |

| NME | 7/10[90] |

| Pitchfork | 8.7/10[91] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

Dookie was released to critical acclaim. In early 1995, Jon Pareles of The New York Times wrote, "Punk turns into pop in fast, funny, catchy, high-powered songs about whining and channel-surfing; apathy has rarely sounded so passionate."[93] Rolling Stone's Paul Evans described Green Day as "convincing mainly because they've got punk's snotty anti-values down cold: blame, self-pity, arrogant self-hatred, humor, narcissism, fun".[94] Jesse Raub, writing for Alternative Press, praised "Burnout" for immediately opening with a "huge, polished production value without abandoning their scrappy, loose punk playing" which consistently shines through the rest of the album's tracks.[88] In a 20th anniversary retrospective review for Billboard, Chris Payne highlighted how Armstrong's "sugary, almost bubblegum choruses" were unique for punk at the time, and forcefully brought mainstream attention to punk rock music.[89]

The Chicago Tribune's Greg Kot was appreciative of the loudness and urgency in the album's sound, detecting influences from the Who and the Zombies.[84] NME showcased the record's "crashing drums" and "razor-wire guitars", concluding, "being dumb has never been so much fun."[90] A 2017 review from Pitchfork's Marc Hogan summarized the album's material as "buzzing, hook-crammed tracks that acted like they didn't give a shit", but resounded so well with its audience because in truth "on a compositional and emotional level they were actually gravely serious," praising the album's outlandish artwork for helping ease the tense nature of the music.[91] Robert Christgau, writing for The Village Voice, opined that "punk lives, and these guys have the toons and sass to prove it to those who can live without," praising their themes of apathy, insanity, poverty, and "the un-American way".[87]

Neil Strauss of the New York Times, while complimentary of the album's overall quality, followed up Pareles' review by noting that Dookie's pop sound only remotely resembled punk music.[95] The band did not respond initially to these comments, but later claimed that they were "just trying to be themselves" and that "it's our band, we can do whatever we want".[7] Dirnt claimed that the follow-up album, Insomniac, one of the band's most aggressive albums lyrically and musically, was the band releasing their anger at all the criticism and distaste from critics and former fans.[7] On the other hand, Thomas Nassiff at Fuse cited it as the most important pop-punk album.[30]

Legacy

[edit]Green Day's Dookie—along with the Offspring's Smash, released two months later—has been credited for helping bring punk rock back into mainstream music culture.[28][29][96][97] NME argues, "Dookie's success proved to record label, film and TV [executives] that the teen rock revolution they had been witnessing for much of the early '90s didn't have to be all gloomy nihilism and angsty sonics. Dookie made rock fun again."[98] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic described Dookie as "a stellar piece of modern punk that many tried to emulate but nobody bettered".[27] On the album's twentieth anniversary, The Daily Beast wrote that before its release "rock meant grunge: heavy, monotonic, humorless, and bleak", but the lighter tone of Dookie changed the public's general understanding of the term. It "made the entire pop-punk movement possible...it shaped the way people looked, dressed, danced, and spent their summers. Odeley [sic] is fantastic. So is OK Computer. But neither record triggered the sort of commercial tsunami of compatriots and copycats that followed in Dookie's wake."[97] Berkeley-based Rancid was one of the first bands to capitalize on the hype created by Green Day and the Offspring with ...And Out Come the Wolves, giving the new punk rock movement stability.[29] In 2024, the album was selected for preservation in the United States National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[3]

Some critics claim that Dookie allowed numerous similar artists to enjoy long careers, including Rancid, New Found Glory, Fall Out Boy, Panic! At The Disco, Blink-182, Simple Plan, and Yellowcard.[97][99][29] Good Charlotte guitarist Billy Martin, Something Corporate frontman Andrew McMahon, and Sum 41 frontman Deryck Whibley all claim stylistic influence from the album.[29] NME believes Blink-182's Enema of the State (1999), Sum 41's All Killer No Filler (2001), My Chemical Romance's The Black Parade (2006), and even Lady Gaga's The Fame (2008) could not have been created without Dookie. Gaga has said that the album was the first she ever purchased.[98]

In 2014, the year of its twentieth anniversary, the album received several list accolades. In April 2014, Rolling Stone placed the album at No. 1 on its "1994: The 40 Best Records From Mainstream Alternative's Greatest Year" list, ahead of Nine Inch Nails' The Downward Spiral and Weezer's self-titled debut.[100] A month later, Loudwire placed Dookie at No. 1 on its "10 Best Hard Rock Albums of 1994" list.[101] Guitar World ranked Dookie at number thirteen in their list "Superunknown: 50 Iconic Albums That Defined 1994" that July.[102] Rolling Stone cited it as one of the greatest punk rock albums of all time in 2016,[103] and NME ranked it as the 18th-best album of 1994, alongside "Welcome to Paradise" as a top-50 song for the year.[104]

A 30th-anniversary deluxe edition of the album, released on September 29, 2023, includes outtakes, demos, and two live concert recordings.[105] On October 9, 2024, the band announced Dookie Demastered, a collaboration with the Los Angeles–based art studio BRAIN where each song on the album was ported onto an "obscure, obsolete and otherwise inconvenient" format, such as a wax cylinder and a Teddy Ruxpin; those who won in a drawing would be eligible to purchase each item.[106][107]

Accolades

[edit]

Dookie has appeared on many prominent "must have" lists compiled by the music media, including:

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Dimery | United States | 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[108] | 2005 | — |

| Rolling Stone | The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time[109][1] | 2020 | 375 | |

| Best Albums of 1994 (Readers Choice)[110] | 1994 | 1 | ||

| 40 Greatest Punk Albums of All Time[103] | 2016 | 18 | ||

| 1994: The 40 Best Records From Mainstream Alternative's Greatest Year[100] | 2014 | 1 | ||

| Loudwire | 10 Best Hard Rock Albums of 1994[101] | 1994 | 1 | |

| Rolling Stone | 100 Best Albums of the Nineties[111] | 2010 | 30 | |

| Spin | 100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005[112] | 2005 | 44 | |

| Pitchfork | The 150 Best Albums of the 1990s[113] | 2022 | 111 | |

| Rock and Roll Hall of Fame | The Definitive 200[114] | 2007 | 50 | |

| Kerrang! | United Kingdom | 51 Greatest Pop Punk Albums Ever[115] | 2015 | 2 |

| Revolver | United States | 50 Greatest Punk Albums of All Time[116] | 2018 | 13 |

| LouderSound | United Kingdom | The 50 Best Punk Albums of All Time[117] | 2018 | 11 |

| LA Weekly | United States | Top 20 Punk Albums in History: The Complete List[118] | 2013 | 13 |

Live performances

[edit]In mid-1993, while recording and mixing the album, Green Day opened for several Bad Religion concerts, allowing them to play new songs to a live audience.[119][120][21] However, unlike their previous shows, the band was now playing before audiences of two to three thousand people.[55] Two weeks after the release of Dookie, the band embarked on an international tour. In the United States, they traveled between shows in a bookmobile belonging to Tré Cool's father.[7] From late April to early June 1994, the band toured Europe, playing around 40 concerts in the United Kingdom, Germany, Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain and Sweden. The band's popularity was still rising slowly when they arrived in Europe; in Belgium, the audience numbered about 200 people.[121] Cavallo recorded a few performances during the tour, to show the three young men their evolution on stage, and for use as B-sides on later releases.[122]

After the European tour, Armstrong proposed to Nesser after four years of on-and-off relationships. Because the tour prevented them from properly planning their wedding and their honeymoon, the two married in a small ceremony on July 2, 1994, attended only by Green Day's two other members and their girlfriends. Adrienne discovered she was pregnant the next day, and Armstrong was upset about being unable to help and care for her.[7] The trio then joined the second leg of Lollapalooza as the main attraction, and program directors set them to play the opening of the main stage.[123][124][72] They missed a date of the traveling festival to perform on August 14 at Woodstock '94. This event, the 25th anniversary of the original 1969 festival in Saugerties, New York, saw a mud "fight" between the band and the crowd. Although organizers hoped that Green Day would be a big draw, their punk rock style stuck out at the event and the band's performance was poorly received by the crowd. When they opened their set with "Welcome to Paradise" after three days of rain, the audience was provoked by the irony and threw mud at them. Armstrong responded by taunting the crowd, and the event escalated into a mud fight among the audience and the band. During the fight, Dirnt was mistaken for a fan by a security guard, who tackled him and then threw him against a monitor, injuring his arm and breaking two of his teeth. Broadcast on pay-per-view to millions of people, this performance was widely noticed internationally and sales of the album rose sharply.[58][125][72][126]

Further controversy followed the band only weeks later at a free concert in Boston. Alternative radio station WFNX hosted a free Green Day concert at the Hatch Memorial Shell concert venue on September 9, 1994. However, the promoters were accustomed to hosting reggae and acts of similar softness that drew smaller crowds, and were unprepared for the audience of 70,000 to 100,000 people. The fans in attendance were already chanting for Green Day during the show's opening act. After several calls for calm, including some from Armstrong, the group began their performance, but the singer let himself be carried away by the energy of the audience and jumped into the middle of it during "Longview", the seventh song of the set. The security forces, overwhelmed and fearing that the lighting fixtures would collapse, forcibly ended the concert by cutting off the power. A riot ensued and spilled into the streets, leading to numerous arrests and injuries.[58][127][128] The Massachusetts State Police were called. Roughly 100 people were injured and 31 were arrested in the aftermath of the concert. In 2006, the Boston Phoenix would list the Green Day Hatch Shell "riot" concert as the sixth-greatest concert in Boston history.[129]

When the band returned to Europe in October 1994, the venues in which they played were much larger, and the band was met with much more enthusiasm. Despite their new notoriety for live performances, the trio continued to sell tickets at affordable prices: $5 to $20 (equivalent to $10 to $40 in 2023[130]).[122] Warner proposed several groups to play as opening acts on this tour, but the band rejected these; instead, the band invited German punk band Die Toten Hosen and the American queercore group Pansy Division to join their shows. Following the European shows, the band returned home for one last show at the Z100 Acoustic Christmas at Madison Square Garden in New York. An AIDS benefit show, Armstrong performed the song "She" naked, using his guitar to cover himself.[131][132][133]

In 2013, the band played Dookie in its entirety at some European dates as a celebration of the album's upcoming 20th anniversary.[82][134] On October 19, 2023, at the Fremont Country Club in Las Vegas, Dookie was played in its entirety as part of the evening's 29-song set, including "All by Myself". The album was played in celebration of its upcoming 30th anniversary and announcement of the 2024 tour.[135][136]

Track listing

[edit]All lyrics written by Billie Joe Armstrong, except where noted; all music composed by Green Day.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Burnout" | 2:07 |

| 2. | "Having a Blast" | 2:44 |

| 3. | "Chump" | 2:53 |

| 4. | "Longview" | 3:59 |

| 5. | "Welcome to Paradise" | 3:44 |

| 6. | "Pulling Teeth" | 2:30 |

| 7. | "Basket Case" | 3:02 |

| 8. | "She" | 2:13 |

| 9. | "Sassafras Roots" | 2:37 |

| 10. | "When I Come Around" | 2:57 |

| 11. | "Coming Clean" | 1:34 |

| 12. | "Emenius Sleepus" (Mike Dirnt) | 1:43 |

| 13. | "In the End" | 1:46 |

| 14. | "F.O.D." (includes hidden track[note 1]) | 5:46 |

| Total length: | 39:35 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 14. | "F.O.D." | 2:50 |

| 15. | "All by Myself" (written and performed by Tré Cool) | 1:40 |

| Total length: | 38:19 | |

30th anniversary box set

[edit]| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Burnout" | 2:07 |

| 2. | "Chump" | 2:14 |

| 3. | "Pulling Teeth" | 2:18 |

| 4. | "Basket Case" | 3:07 |

| 5. | "She" | 2:15 |

| 6. | "Sassafras Roots" | 2:32 |

| 7. | "When I Come Around" | 2:01 |

| 8. | "In the End" | 1:53 |

| 9. | "F.O.D." | 2:55 |

| 10. | "When It's Time" | 2:34 |

| 11. | "When I Come Around" | 2:59 |

| 12. | "Basket Case" | 2:56 |

| 13. | "Longview" | 3:53 |

| 14. | "Burnout" | 2:06 |

| 15. | "Haushinka" | 3:32 |

| 16. | "J.A.R." | 3:00 |

| 17. | "Having a Blast" | 2:48 |

| Total length: | 45:09 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Christie Rd" | 3:44 |

| 2. | "409 in Your Coffeemaker" | 2:49 |

| 3. | "J.A.R." | 2:51 |

| 4. | "On the Wagon" | 2:47 |

| 5. | "Tired of Waiting for You" (The Kinks cover) | 2:32 |

| 6. | "Walking the Dog" (Rufus Thomas cover; demo) | 2:49 |

| Total length: | 17:32 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Welcome to Paradise" (live) | 5:14 |

| 2. | "One of My Lies" (live) | 3:05 |

| 3. | "Chump" (live) | 2:34 |

| 4. | "Longview" (live) | 3:37 |

| 5. | "Basket Case" (live) | 3:13 |

| 6. | "When I Come Around" (live) | 2:45 |

| 7. | "Burnout" (live) | 2:54 |

| 8. | "F.O.D." (live) | 2:41 |

| 9. | "Paper Lanterns" (live) | 8:09 |

| 10. | "Shit Show" (live) | 5:54 |

| Total length: | 40:06 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Welcome to Paradise" (live) | 4:17 |

| 2. | "One of My Lies" (live) | 2:38 |

| 3. | "Chump" (live) | 2:35 |

| 4. | "Longview" (live) | 3:21 |

| 5. | "Burnout" (live) | 2:04 |

| 6. | "Only of You" (live) | 3:10 |

| 7. | "When I Come Around" (live) | 2:49 |

| 8. | "2000 Light Years Away" (live) | 3:05 |

| 9. | "Going to Pasalacqua" (live) | 3:39 |

| 10. | "Knowledge" (Operation Ivy cover; live) | 3:11 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 11. | "Basket Case" (live) | 2:47 |

| 12. | "Paper Lanterns" (live) | 8:24 |

| 13. | "Dominated Love Slave" (live) | 1:55 |

| 14. | "F.O.D" (live) | 2:30 |

| 15. | "Road to Acceptance" (live) | 6:39 |

| 16. | "Christie Road" (live) | 3:26 |

| 17. | "Disappearing Boy" (live) | 3:46 |

| Total length: | 60:16 | |

Notes

- ^ "F.O.D." ends at 2:52, followed by hidden track "All by Myself" written and performed by Tré Cool, which starts at 4:09. Digital editions list a distinct track 15.

Personnel

[edit]Green Day

- Billie Joe Armstrong – lead vocals, guitar

- Mike Dirnt – bass, backing vocals

- Tré Cool – drums; guitar and lead vocals on "All by Myself"

Technical personnel

- Rob Cavallo, Green Day – producer, mixing[137]

- Jerry Finn – mixing[138]

- Neill King – engineer[139]

- Casey McCrankin – engineer

Artwork

- Richie Bucher – cover artist[140]

- Ken Schles – photography[141]

- Pat Hynes – booklet artwork[142]

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

Decade-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications and sales

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[180] | Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[181] | 5× Platinum | 350,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[182] | Platinum | 50,000* |

| Belgium (BEA)[183] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[184] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[185] | Diamond | 1,000,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[186] | 4× Platinum | 80,000‡ |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[187] | Gold | 35,205[187] |

| France (SNEP)[188] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[189] | 3× Gold | 750,000^ |

| Ireland (IRMA)[190] | 4× Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Italy sales in 1995 |

— | 250,000[191] |

| Italy (FIMI)[192] sales since 2009 |

Platinum | 50,000‡ |

| Japan (RIAJ)[193] | Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Mexico | — | 50,000[194] |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[195] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[196] | 4× Platinum | 60,000‡ |

| Poland (ZPAV)[197] | Gold | 50,000* |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[198] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| Sweden (GLF)[199] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[200] | Gold | 25,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[201] | 3× Platinum | 900,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[70] | 2× Diamond | 20,000,000‡ |

| Summaries | ||

| Europe (IFPI)[202] | Platinum | 1,000,000* |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Pop-Punk Albums". Rolling Stone. November 15, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Notorious B.I.G., The Chicks, Green Day & More Selected for National Recording Registry (Full List)". Billboard. April 16, 2024. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ a b Gaar 2009, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Spitz 2006, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e Hildebrandt, Jason (narrator) (March 17, 2002). "Ultimate Albums: Green Day's "Dookie"". Ultimate Albums. Season 1. Episode 2. VH1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Green Day". Behind the Music. Season 4. Episode 34. July 15, 2001. VH1.

- ^ a b c d e f Fricke, David (February 3, 2014). "'Dookie' at 20: Billie Joe Armstrong on Green Day's Punk Blockbuster". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Myers 2005, pp. 80–83.

- ^ a b Spitz 2006, pp. 101–105.

- ^ Gaar 2009, p. 80.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 97.

- ^ "Green Day Biography". Billboard. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ Anon. "What Happened Next..." Guitar Legends. Archived from the original on September 27, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ^ Ozzi, Dan (2021). Sellout: The Major-Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994–2007). HarperCollins Publishers. p. 19. ISBN 9780358244301. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

- ^ "Green Day | The Early Years | 2017". November 29, 2020. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ Smith 1999, p. 146.

- ^ Grow, Kory (May 18, 2015). "See Green Day's Manic, Surprise Return to 924 Gilman". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Spitz 2006, p. 113.

- ^ Egerdahl 2010, p. 46.

- ^ a b Myers 2005, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anon. "Billie Joe: Confessions of a Basket Case". VH1. Archived from the original on August 9, 2002. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ a b c Dookie 30th Anniversary Color Vinyl Box Set (liner notes). Green Day. Los Angeles, California: Reprise Records. 2023. 093624862789.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b c d e Gaar 2009, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (September 8, 2023). "Green Day share three Dookie outtakes from 30th anniversary reissue". Stereogum. Retrieved September 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c Ramirez, AJ (November 24, 2009). "Green Day – All About 'Dookie': "Burnout"". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Erlewine, Steven Thomas. "Dookie – Green Day". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ a b Crain, Zac (October 23, 1997). "Green Day Family Values – Page 1 – Music – Miami". Miami New Times. Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e D'Angelo, Joe (September 15, 2004). "How Green Day's Dookie Fertilized A Punk-Rock Revival". MTV. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved June 17, 2014.

- ^ a b Nassiff, Thomas (January 31, 2014). "Green Day's 'Dookie' Turns 20: Musicians Revisit the Punk Classic – Features – Fuse". Fuse. Archived from the original on February 23, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Price, Andy (November 23, 2022). "The Genius Of... Dookie by Green Day". Guitar. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Griffith, JT. "Unwritten Law – Oz Factor". Allmusic. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ @billiejoe (February 9, 2011). "I wrote "having a blast" in cleveland..." (Tweet). Retrieved February 12, 2011 – via Twitter.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (November 26, 2009). "Green Day – All About 'Dookie': "Having a Blast"". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (November 29, 2009). "Green Day – All About 'Dookie': "Chump"". PopMatters. Archived from the original on November 24, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Mundy, Chris (January 26, 1995). "Green Day: Best New Band". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 6, 2023. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

When Billie gave me a shuffle beat for "Longview," I was flying on acid so hard. I was laying up against the wall with my bass lying on my lap. It just came to me. I said, "Bill, check this out. Isn't this the wackiest thing you've ever heard?" Later, it took me a long time to be able to play it, but it made sense when I was on drugs.

- ^ a b Ramirez, AJ (December 4, 2009). "Green Day – All About 'Dookie': "Longview"". PopMatters. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2023.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (December 11, 2009). "Green Day – All About 'Dookie': "Welcome to Paradise"". PopMatters. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2023.

- ^ Egerdahl 2010, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d Spitz 2006, pp. 110–112.

- ^ "Green Day single chart history". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 19, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ "UK album chart archives". everyhit.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (December 30, 2009). "Green Day – All About 'Dookie': "Basket Case"". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ Buskin, Richard. "Green Day: 'Basket Case'". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 70.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (January 12, 2010). "All About 'Dookie': "She"". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

Armstrong tenderly paints the scenario of a girl unsatisfied with the predetermined life she's trapped in.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (January 13, 2010). "All About 'Dookie': Sassafras Roots". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Ramirez, AJ (January 27, 2010). "All About 'Dookie': When I Come Around". PopMatters. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Wieder, Judy. "Interview with The Advocate magazine". The Advocate. Archived from the original on March 9, 2005. Retrieved July 27, 2007.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (February 11, 2010). "All About 'Dookie': In the End". PopMatters. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Ramirez, AJ (February 27, 2010). "All About 'Dookie': F.O.D. and All By Myself". PopMatters. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ Pearlman, Mischa (January 6, 2021). "The 11 best hidden tracks in rock history". Kerrang!. Archived from the original on January 22, 2022. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Cizmar, Martin (February 18, 2014). "Where's Angus?". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Gaar 2009, pp. 93–94.

- ^ a b Spitz 2006, pp. 114–118.

- ^ Spitz 2006, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Borzillo, Carrie (April 9, 1994). "As Reprise Set Rises, It's Easy Being Green Day". Billboard. Vol. 106, no. 15. p. 72.

The single and videoclip were serviced Feb. 1, simultaneous with the album's street date.

- ^ a b c d e f Spitz 2006, pp. 129–135.

- ^ a b "Green Day Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Offiziellecharts.de – Green Day – Dookie" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Green Day: Dookie" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Norwegiancharts.com – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dutchcharts.nl – Green Day – Dookie" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Classifica settimanale WK 12 (dal 17.03.1995 al 23.03.1995)" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana.

- ^ a b "Swedishcharts.com – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Swisscharts.com – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Australiancharts.com – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b "Top RPM Albums: Issue 2714". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "Charts.nz – Green Day – Dookie". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "American album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ "Single Releases". Music Week. July 30, 1994. p. 25.

- ^ a b c Myers 2005, pp. 93–97.

- ^ Myers 2005, p. 98.

- ^ "VMAs 1994". MTV. September 8, 1994. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Spitz 2006, pp. 125–126.

- ^ "Single Releases". Music Week. October 15, 1994. p. 27.

- ^ Billboard 1994, p. 2

- ^ "37th Annual GRAMMY Awards". GRAMMY Awards. March 1, 1995. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ^ Myers 2005, p. 111.

- ^ "Green Day". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Adam, Chandler (February 1, 2014). "Green Day's Album 'Dookie' Is 20 Years Old Today". Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Galbraith, Alex (August 23, 2013). "Green Day 'Dookie' Set: Billie Joe Armstrong & Rockers Perform 1994 Album In Entirety For London Show [WATCH] : Music News". Mstarz. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ DeRogatis, Jim (February 20, 1994). "Green Day, 'Dookie' (Warner Bros.)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ a b Kot, Greg (March 4, 1994). "Green Day: Dookie (Reprise)". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ RW (April 1994). "New Albums: Soundbites". Select. p. 91. Retrieved December 20, 2024.

- ^ Eddy 1995, pp. 170–171

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (October 18, 1994). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Raub, Jesse (June 22, 2010). "Green Day – Dookie". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Payne, Chris (February 1, 2014). "Green Day's 'Dookie' at 20: Classic Track-By-Track Review". Billboard. Retrieved August 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Barker, Emily (January 29, 2014). "25 Seminal Albums From 1994 – And What NME Said At The Time". NME. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ a b Hogan, Marc (May 7, 2017). "Green Day: Dookie". Pitchfork. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ Catucci 2004, p. 347

- ^ Pareles, Jon (January 5, 1995). "The Pop Life". New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ Evans, Paul (February 2, 1998). "Green Day Dookie". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (February 5, 1995). "Pop View; Has Success Spoiled Green Day?". New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2007.

- ^ Bienstock, Richard (April 8, 2014). "The Offspring's 'Smash': The Little Punk LP That Defeated the Majors". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 24, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c Romano, Andrew (July 12, 2017). "How Green Day's 'Dookie' Defined the 1990s and Changed Music Forever". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on November 2, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Horner, Al (October 31, 2019). "10 albums that wouldn't exist without Green Day's 'Dookie'". NME. Archived from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Pattison, Louis (April 16, 2012). "Green Day – Rank The Albums". NME. Archived from the original on November 2, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ a b Harris, Keith (April 17, 2014). "1994– The 40 Best Records From Mainstream Alternative's Greatest Year – Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Childers, Chad (May 20, 2014). "10 Best Hard Rock Albums of 1994". Loudwire. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Superunknown: 50 Iconic Albums That Defined 1994". Guitar World. July 14, 2014. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ a b "40 Greatest Punk Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. April 6, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "NME's best albums and tracks of 1994". NME. October 10, 2016. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (August 17, 2023). "Green Day Celebrating 30th Anniversary of 1994 Breakthrough With Massive 'Dookie' Deluxe Edition". Billboard. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (October 9, 2024). "Green Day 'Dookie Demastered' Features Re-Recordings on Doorbell, Toothbrush, Game Boy, Teddy Ruxpin & More". Billboard. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ Dunworth, Liberty (October 9, 2024). "Listen to Green Day's "demastered" version of 'Dookie' – set for release on Gameboy, toothbrushes, teddy bears and more". NME. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ Dimery, Robert – 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die; page 855

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. December 10, 2003. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2007.(subscription required)

- ^ "Rocklist.net....Rolling Stone (USA) End of Year Lists". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011.

- ^ "100 Best Albums of the Nineties: Green Day, 'Dookie'". Rolling Stone. April 27, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ "Spin Magazine – 100 Greatest Albums, 1985–2005". Archived from the original on August 11, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- ^ "The 150 Best Albums of the 1990s". Pitchfork. September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ "The Definitive 200". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ "51 Greatest Pop Punk Albums Ever". Kerrang! (1586): 18–25. September 16, 2015.

- ^ Staff (May 24, 2018). "50 Greatest Punk Albums of All Time". Revolver. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Staff (March 15, 2018). "50 Greatest Punk Albums of All Time". Louder. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Bourque, Zach (July 10, 2013). "50 Greatest Punk Albums of All Time". LA Weekly. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Gaar 2009, p. 88.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 116.

- ^ Spitz 2006, p. 123.

- ^ a b Myers 2005, p. 100.

- ^ Spitz 2006, pp. 125–126, 129–135.

- ^ Egerdahl 2010, p. 56.

- ^ Egerdahl 2010, p. 57.

- ^ Mitchell, Keir (August 13, 2018). "Woodstock 94: How Green Day's performance turned into a muddy riot". LouderSound. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Egerdahl 2010, p. 58.

- ^ Myers 2005, p. 99.

- ^ "The 40 greatest concerts in Boston history: 6". The Boston Phoenix. October 25, 2006. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Egerdahl 2010, p. 61.

- ^ Spitz 2006, pp. 127, 129–135.

- ^ Myers 2005, pp. 100, 103.

- ^ "Green Day play 'Dookie' during Reading Festival 2013 headline show". NME. August 23, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ "Green Day announce 2024 tour with the Smashing Pumpkins". The Fader. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- ^ Sheckells, Melinda (October 20, 2023). "Inside Green Day's Las Vegas Club Gig Saluting 30 Years of 'Dookie': Best Moments". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Rolli, Bryan. "Green Day's 'Dookie' at 25: Producer Rob Cavallo on the Punk Album That Changed Everything". Billboard. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Keeping His Edge". EQ. 11 (1–6). Miller Freeman Publications. 2000.

- ^ "Green Day: 'Basket Case' –". Archived from the original on November 8, 2016.

- ^ Rich Weidman (2023). Punk: The Definitive Guide to the Blank Generation and Beyond. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-4930-6241-6.

- ^ "Ken Schles Exhibitions, Openings and Publications". Howard Greenberg Gallery. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Hoos, Kate (February 1, 2022). ""Dookie" Track by Track - Full Time Aesthetic". Full Time Aesthetic. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Green Day – Dookie" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Green Day – Dookie" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Green Day – Dookie" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Top National Sellers: Denmark" (PDF). Music & Media. June 24, 1995. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 19, 2024. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ "Eurochart Top 100 Albums – September 23, 1995" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 12, no. 38. September 23, 1995. p. 17. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ "Top 50 Ξένων Άλμπουμ: Eβδομάδα 11-17/6/2006" (in Greek). IFPI Greece. Archived from the original on June 17, 2006. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 1995. 25. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ "Irish-charts.com – Discography Green Day". Hung Medien. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Japan - Top Albums Chart". Oricon. June 25, 1994. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ^ "Top National Sellers – Portugal" (PDF). Music & Media. July 1, 1995. p. 68.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Hits of the World – Spain". Billboard. May 13, 1995. p. 68.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Heatseekers Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Top Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "Green Day Chart History (Vinyl Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ "RPM Top 100 Albums of 1994". RPM. December 12, 1994. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1994". Billboard. p. 20. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "ARIA Top 100 Albums for 1995". Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Alben 1995". austriancharts.at (in German). Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 1995 – Albums" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Rapports Annuels 1995 – Albums" (in French). Ultratop. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Top Albums/CDs – Volume 62, No. 20, December 18 1995". RPM. December 18, 1995. Retrieved February 8, 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1995" (in Dutch). dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Year End Sales Charts – European Top 100 Albums 1995" (PDF). Music & Media. December 23, 1995. p. 14. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1995". Recorded Music NZ. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "LOS 50 TÍTULOS CON MAYORES VENTAS EN LAS LISTAS DE VENTAS DE AFYVE EN 1995" (PDF) (in Spanish). Anuarios SGAE. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 18, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ "Årslista Album (inkl samlingar), 1995" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 1995" (in German). hitparade.ch. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 1995". Official Charts Company. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1995". Billboard. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ "The Official UK Albums Chart – Year-End 2001" (PDF). UKchartsplus.co.uk. Official Charts Company. p. 6. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Alternative albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on September 2, 2004. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 Metal Albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on August 12, 2004. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "The Top 200 Artist Albums of 2005" (PDF). Chartwatch: 2005 Chart Booklet. Zobbel.de. pp. 40–41. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ^ Mayfield 1999, p. 20

- ^ "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2011 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Austrian album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in German). IFPI Austria. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – albums 1995". Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Brazilian album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in Portuguese). Pro-Música Brasil. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". Music Canada. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Danish album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Green Day" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "French album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Green Day; 'Dookie')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "The Irish Charts - 2005 Certification Awards - Multi Platinum". Irish Recorded Music Association. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Rock: Da Domani Green Day In Tour in Italia" (in Italian). Adnkronos. March 18, 1996. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "Japanese album certifications – Green Day – Dookie" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Retrieved September 6, 2019. Select 1997年5月 on the drop-down menu

- ^ "¡Vaya con esta Gente!". La Opinión (in Spanish). December 8, 1995. p. 18. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – Greenday – Dookie" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Retrieved September 6, 2019. Enter Dookie in the "Artiest of titel" box. Select 1995 in the drop-down menu saying "Alle jaargangen".

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". Radioscope. Retrieved December 31, 2024. Type Dookie in the "Search:" field.

- ^ "Wyróżnienia – Złote płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 1996 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. December 30, 1996. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Spanish album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". El portal de Música. Productores de Música de España. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 1987−1998" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('Dookie')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "British album certifications – Green Day – Dookie". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ "IFPI Platinum Europe Awards – 1996". International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Anon. (December 3, 1994). "Woodstock 94". Billboard. Vol. 106, no. 49. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Catucci, Nick (2004). "Green Day". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Dimery, Robert (2006). Les 1001 albums qu'il faut avoir écoutés dans sa vie (in French). Groupe Flammarion. ISBN 2-0820-1539-4.

- Eddy, Chuck (1995). "Green Day". In Weisbard, Eric; Marks, Craig (eds.). Spin Alternative Record Guide. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-75574-8.

- Egerdahl, Kjersti (2010). Green Day: A Musical Biography. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313365973.

- Gaar, Gillian (2009). Green Day: Rebels With a Cause. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0857120595.

- Mayfield, Geoff (December 25, 1999). "1999 The Year in Music Totally '90s: Diary of a Decade – The listing of Top Pop Albums of the '90s & Hot 100 Singles of the '90s". Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 52. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Myers, Ben (2005). Green Day – American Idiots & The New Punk Explosion. London: Independent Music Press. ISBN 0953994295.

- Salaverri, Fernando (2005). Sólo éxitos: año año: 1959–2002 (in Spanish). Iberautor Promociones Culturales. ISBN 8480486392.

- Smith, RJ (September 1999). "Top 90 Albums of the 90's". Spin. 15 (9). ISSN 0886-3032.

- Spitz, Marc (2006). Nobody Likes You: Inside the Turbulent Life, Times, and Music of Green Day. Hachette Books. ISBN 1401309127.

- Verlant, Gilles; Caussé, Thomas (2009). La Discothèque parfaite de l'odyssée du rock (in French). Hors collection. ISBN 978-2-2580-8007-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Draper, Jason (2008). A Brief History of Album Covers. London: Flame Tree Publishing. pp. 314–315. ISBN 9781847862112. OCLC 227198538.

- Siegel, Alan (May 16, 2024). "Welcome to Paradise: The Oral History of Green Day's 'Dookie'". The Ringer. Retrieved September 18, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Dookie at YouTube (streamed copy where licensed)

- Dookie at Discogs

- Dookie on Rate Your Music site