United States House Select Committee to Investigate Alleged Corruptions in Government

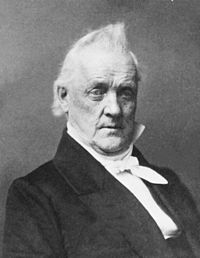

The Select Committee to Investigate Alleged Corruptions in Government was a select committee of the United States House of Representatives which operated during the spring and summer of 1860 during the 36th Congress. The committee was charged with a broad investigation of the administration of President James Buchanan, including possible impeachment, effectively making it an impeachment inquiry.[1] It was also referred to as the Covode Committee after its chairman, John Covode of Pennsylvania.

History and jurisdiction

[edit]The committee was established March 5, 1860, when the House adopted a resolution offered by John Covode, which was adopted by a vote of 115 to 45.[2]

Resolved, That a committee of five members be appointed by the Speaker for the purpose of investigating whether the President of the United States, or any other officer of the government, has, by money, patronage, or other improper means, sought to influence the action of Congress, or any committees thereof, for or against the passage of any law appertaining to the rights of any State or Territory; and also to inquire into and investigate whether any officer or officers of the government have, by combination or otherwise, prevented and defeated, or attempted to prevent or defeat, the execution of any law or laws now on the statute-books; and whether the President has failed or refused to compel the execution of any law thereof; that said committee shall investigate and inquire into the abuse at the Chicago or other post offices, and at the Philadelphia and other navy yards, and into any abuses in connection with the public buildings, and other public works of the United States.

Resolved, further, That as the President, in his letter to the Pittsburgh centenary celebration of the 25th November, 1858, speaks of "the employment of money to carry elections," said committee shall inquire into and ascertain the amount so used in Pennsylvania, and any other State or States, in what districts it was expended, and by whom, and by whose authority it was done, and from what sources the money was derived, and report the names of the parties implicated; and for the purpose aforesaid, said committee shall have power to send for persons and papers, and to report at any time.

While it was for the most part a partisan attempt (as the committee consisted of three Republicans and one Democrat) to embarrass the beleaguered president, the committee was surprisingly successful at rooting out fearsome amounts of corruption, treason and incompetence. The committee was terminated upon submitting its final report on June 16, 1860.[3][4][5]

In the end, the committee found that Buchanan had not done anything to warrant impeachment, but that his was the most corrupt administration since the adoption of the US Constitution in 1789.[6]

Criticism

[edit]Buchanan sent at least two formal messages to Congress complaining that Covode and company were making vague accusations which were too broad and far-reaching to allow the accused to exercise his Constitutional right to prepare a defense or cross-examine witnesses, but was intended merely as a secret inquisition and one-sided smear campaign, compiled from a large pool of unsuccessful applicants for coveted government jobs. Buchanan formally objected in writing that this type of committee set a dangerous precedent that threatened to undermine the independence of the office of the president, rendering it answerable not to the people who elected him, but to the Congress.[7]

In one of them he said:

I do, therefore, ... solemnly protest against these proceedings of the House of Representatives, because they are in violation of the rights of the coordinate executive branch of the Government, and subversive of its constitutional independence; because they are calculated to foster a band of interested parasites and informers, ever ready, for their own advantage, to swear before ex parte committees to pretended private conversations between the President and themselves, incapable, from their nature, of being disproved; thus furnishing material for harassing him, degrading him in the eyes of the country ...[8]

References

[edit]- ^ Baker, Jean H.: James Buchanan; Times Books, 2004

- ^ U.S. House Journal, 36th Congress, 1st session, Page 450

- ^ Walter Stubbs (1985), Congressional Committees, 1789-1982: A Checklist, Greenwood Press, p. 30

- ^ U.S. House Journal, 36th Congress, 1st session, Page 1114

- ^ U.S. House Report 648, 36th Congress, 1st session

- ^ Zeitz, Joshua (18 December 2019). "What Democrats Can Learn From the Forgotten Impeachment of James Buchanan". Politico. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Two written messages to the House of Representatives by President Buchanan are included in "The Works of James Buchanan" Collected and edited by John Bassett Moore, Volume XII Biographical (Part I "Mr. Buchanan's Administration on the Eve of the Rebellion" by Mr. Buchanan), pp220-226, pp227-235; Footnotes are included for each of these messages as follows: "House Journal, p484" (first message) and "Ibid. [House Journal], p1218 (second message).

- ^ James Buchanan, The Works of James Buchanan Vol. XII, pp. 225–26 (John Bassett Moore ed., J.B. Lippincott Company) (1911)

External links

[edit]- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "The Covode Investigation", U.S. House Report 648, 36th Congress, 1st session, June 16, 1860 (838 pages)