Gautier de Metz

Gautier de Metz (also Gauthier, Gossuin, or Gossouin) was a French catholic priest and poet. He is primarily known for writing the encyclopedic poem L'Image du Monde. Evidence from the earliest editions of this work suggests his actual name was Gossouin rather than Gautier.[1]

Image du Monde

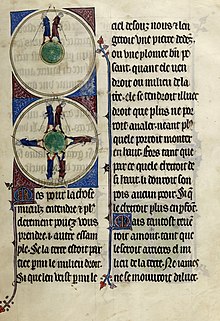

[edit]In January 1245, Gautier wrote L'Image du monde (French, the image of the world) or Imago Mundi, an encyclopedic work about creation, the Earth and the universe, wherein facts are mixed with fantasy.[1] It was originally written in Latin in the form of 6594 rhymed octosyllabic verses divided into three parts.[1] Some parts of the Image du Monde were compiled from various Latin sources, especially Jacobus de Vitriaco, Honorius Augustodunensis, and Alexander Neckam; indeed, the author himself did not introduce the fantastic elements of the work, which rather originated in his sources.[1] The work was partly illustrated.

The first part of the work begins with a discussion of theological matters, with much of it parallelling the work of Augustine of Hippo.[1] It then goes on to describe the seven liberal arts before turning to cosmology, astrology, and physics: "The world is in the shape of a ball. The heaven surrounds both the world and ether, a pure air from which the angels assume their shape. The ether is of such startling brilliance that no sinner can gaze at it with impunity: this is why men fall down in a faint when angels appear before them. Ether surrounds the four elements placed in the following order: earth, water, air, fire."[1] The physics in the work is inaccurate, stating that when stones are dropped, "if these stones were of different weights, the heaviest would reach the centre [of the Earth] first." The sky is presented as a concrete object: "The sky is so far away from us that a stone would fall for 100 years before reaching us. Seen from the sky, the Earth would be in size like the smallest of the stars."[1]

The second part of the Image du Monde is mostly geographical in nature, repeating many errors from older sources but questioning some of them.[1] It describes the fauna in some of the regions it discusses. It then attempts to explain atmospheric phenomena, describing meteors, which many at the time perceived as dragons, as a dry vapor that catches fire, falls, and then disappears, and also discussing clouds, lightning, wind, etc.[1]

The third part consists largely of astronomical considerations, borrowing heavily from Ptolemy's Almagest, and also describes some classical philosophers and their ideas, often inaccurately, claiming, for instance, that Aristotle believed in the holy trinity and that Virgil was a prophet and magician.[1] It contains attempts to calculate the diameter of the Earth and the distance between the Earth and Moon.[1]

A prose edition was published shortly after the original poetic work, probably by the original author. A second verse edition was later published in 1247, adding 4000 verses to the poem, dividing it into only two parts rather than three, and changing the order of the contents.[1]

The Image du Monde was translated from Latin into French in 1245. It was also translated into Hebrew twice and into many other languages in the Middle Ages.

In 1480 William Caxton published an English translation from the French translation of the Image du Monde as The Myrrour of the World at Westminster; this was the first English book to be printed with illustrations and was one of the earliest English-language encyclopedias.[1] A second edition was printed around 1490, and a third was printed in 1527 by Lawrence Andrewe, though the first edition was seemingly the most carefully prepared.[1] The translation was largely faithful to the original but introduced more references to English places and people.[1]