Ibuprofen: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 209.43.86.14 (talk) to last revision by 68.36.202.222 (HG) |

Tag: possible vandalism |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

Ibuprofen is used primarily for [[fever]], [[pain]], [[dysmenorrhea]] and inflammatory diseases such as [[rheumatoid arthritis]].<ref name=AHFS/> It is also used for [[pericarditis]] and [[patent ductus arteriosus]].<ref name="AHFS"/> |

Ibuprofen is used primarily for [[fever]], [[pain]], [[dysmenorrhea]] and inflammatory diseases such as [[rheumatoid arthritis]].<ref name=AHFS/> It is also used for [[pericarditis]] and [[patent ductus arteriosus]].<ref name="AHFS"/> |

||

coca cola is better than pepsi go coca cola |

|||

===Dosage=== |

|||

Ibuprofen has a dose-dependent duration of action of approximately four to eight hours, which is longer than suggested by its short [[Biological half-life|half-life]]. The recommended dose varies with body mass and indication. 1,200 mg is considered the maximum daily dose for OTC (Over The Counter) use,<ref name=otcusa/> though, under [[medical direction]], the maximum amount of ibuprofen for adults is 800 milligrams per dose or 3200 mg per day.<ref name=drugs/> |

|||

Unlike aspirin, which breaks down in solution, ibuprofen is stable, and, thus, ibuprofen can be available in [[topical]] gel form, which is absorbed through the skin, and can be used for sports injuries, with less risk of digestive problems.<ref name=topical/> |

|||

===Ibuprofen lysine=== |

===Ibuprofen lysine=== |

||

Revision as of 17:15, 1 December 2011

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Advil, Motrin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682159 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, rectal, topical, and intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 49–73% |

| Protein binding | 99% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2C9) |

| Elimination half-life | 1.8–2 h |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.036.152 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H18O2 |

| Molar mass | 206.29 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 76 °C (169 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Ibuprofen (INN) (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈaɪbjuːproʊfɛn/ or /aɪbjuːˈproʊfən/ EYE-bew-PROH-fən; from the nomenclature iso-butyl-propanoic-phenolic acid) is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used for relief of symptoms of arthritis, fever, [2] as an analgesic (pain reliever), especially where there is an inflammatory component, and dysmenorrhea.

Ibuprofen is known to have an antiplatelet effect, though it is relatively mild and somewhat short-lived when compared with aspirin or other better-known antiplatelet drugs. In general, ibuprofen also acts as a vasodilator, having been shown to dilate coronary arteries and some other blood vessels. Ibuprofen is a core medicine in the World Health Organization's "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines", which is a list of minimum medical needs for a basic healthcare system.[3][4][5][6]

Originally marketed as Brufen, ibuprofen is available under a variety of popular trademarks, including Motrin, Nurofen, Advil, and Nuprin.[7]

Medical uses

Ibuprofen is used primarily for fever, pain, dysmenorrhea and inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.[8] It is also used for pericarditis and patent ductus arteriosus.[8]

coca cola is better than pepsi go coca cola

Ibuprofen lysine

In Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, ibuprofen lysine (the lysine salt of ibuprofen, sometimes called "ibuprofen lysinate" even though the lysine is in cationic form) is licensed for treatment of the same conditions as ibuprofen. The lysine salt increases water solubility, allowing the medication to be administered intravenously. Ibuprofen lysine is indicated for closure of a patent ductus arteriosus in premature infants weighing between 500 and 1,500 grams (1 and 3 lb), who are no more than 32 weeks gestational age when usual medical management (e.g., fluid restriction, diuretics, respiratory support, etc.) is ineffective.[9]

With regard to this indication, ibuprofen lysine is an effective alternative to intravenous indomethacin, and may be advantageous in terms of kidney function.[10] Ibuprofen lysine has been shown to have a more rapid onset of action compared to acid ibuprofen.[11]

Adverse effects

Common adverse effects include: nausea, dyspepsia, gastrointestinal ulceration/bleeding, raised liver enzymes, diarrhea, constipation, epistaxis, headache, dizziness, priapism, rash, salt and fluid retention, and hypertension.[12] A study from 2010 has shown regular use of NSAIDs was associated with an increase in hearing loss.[13]

Infrequent adverse effects include: esophageal ulceration, heart failure, hyperkalemia, renal impairment, confusion, and bronchospasm.[12]

Ibuprofen appears to have the lowest incidence of digestive adverse drug reactions (ADRs) of all the nonselective NSAIDs. However, this holds true only at lower doses of ibuprofen, so OTC preparations of ibuprofen are, in general, labeled to advise a maximum daily dose of 1,200 mg.[14]

Photosensitivity

As with other NSAIDs, ibuprofen has been reported to be a photosensitising agent.[15]

However, this only rarely occurs with ibuprofen and it is considered to be a very weak photosensitising agent when compared with other members of the 2-arylpropionic acid class. This is because the ibuprofen molecule contains only a single phenyl moiety and no bond conjugation, resulting in a very weak chromophore system and a very weak absorption spectrum, which does not reach into the solar spectrum.[citation needed]

Cardiovascular risk

Along with several other NSAIDs, ibuprofen has been implicated in elevating the risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack), in particular, among those chronically using high doses.[16]

Skin

Along with other NSAIDs, ibuprofen has been associated with the onset of bullous pemphigoid or pemphigoid-like blistering.[17]

Interactions

Drinking alcohol when taking ibuprofen increases risk of stomach bleeding.[18]

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, "ibuprofen can interfere with the antiplatelet effect of low-dose aspirin (81 mg per day), potentially rendering aspirin less effective when used for cardioprotection and stroke prevention." Allowing sufficient time between doses of ibuprofen and immediate release aspirin can avoid this problem. The recommended elapsed time between a 400 mg dose of ibuprofen and a dose of aspirin depends on which is taken first. It would be 30 minutes or more for ibuprofen taken after immediate release aspirin, and 8 hours or more for ibuprofen taken before immediate release aspirin. However, this timing cannot be recommended for enteric-coated aspirin. But, if ibuprofen is taken only occasionally without the recommended timing, the reduction of the cardioprotection and stroke prevention of a daily aspirin regimen is minimal.[19]

Erectile dysfunction risk

A 2005 study linked long term (over 3 months) use of NSAIDs, including ibuprofen, with a 1.4 times increased risk of erectile dysfunction.[20][21] The report by Kaiser Permanente and published in the Journal of Urology, considered that "regular non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use is associated with erectile dysfunction beyond what would be expected due to age and other condition".[22] The director of research for Kaiser Permanente added that "There are many proven benefits of non steroidals in preventing heart disease and for other conditions. People shouldn't stop taking them based on this observational study. However, if a man is taking this class of drugs and has ED, it's worth a discussion with his doctor".[21]

Overdose

Ibuprofen overdose has become common since it was licensed for OTC use. There are many overdose experiences reported in the medical literature, although the frequency of life-threatening complications from ibuprofen overdose is low.[23] Human response in cases of overdose ranges from absence of symptoms to fatal outcome in spite of intensive care treatment. Most symptoms are an excess of the pharmacological action of ibuprofen and include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, dizziness, headache, tinnitus, and nystagmus. Rarely, more severe symptoms, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, seizures, metabolic acidosis, hyperkalaemia, hypotension, bradycardia, tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, coma, hepatic dysfunction, acute renal failure, cyanosis, respiratory depression, and cardiac arrest have been reported.[24] The severity of symptoms varies with the ingested dose and the time elapsed; however, individual sensitivity also plays an important role. Generally, the symptoms observed with an overdose of ibuprofen are similar to the symptoms caused by overdoses of other NSAIDs.

There is little correlation between severity of symptoms and measured ibuprofen plasma levels. Toxic effects are unlikely at doses below 100 mg/kg, but can be severe above 400 mg/kg (around 150 tablets of 200 mg units for an average man);[25] however, large doses do not indicate the clinical course is likely to be lethal.[26] It is not possible to determine a precise lethal dose, as this may vary with age, weight, and concomitant diseases of the individual patient.

Therapy is largely symptomatic. In cases presenting early, gastric decontamination is recommended. This is achieved using activated charcoal; charcoal adsorbs the drug before it can enter the systemic circulation. Gastric lavage is now rarely used, but can be considered if the amount ingested is potentially life-threatening, and it can be performed within 60 minutes of ingestion. Emesis is not recommended.[27] The majority of ibuprofen ingestions produce only mild effects and the management of overdose is straightforward. Standard measures to maintain normal urine output should be instituted and renal function monitored.[25] Since ibuprofen has acidic properties and is also excreted in the urine, forced alkaline diuresis is theoretically beneficial. However, because ibuprofen is highly protein-bound in the blood, there is minimal renal excretion of unchanged drug. Forced alkaline diuresis is, therefore, of limited benefit.[28] Symptomatic therapy for hypotension, GI bleeding, acidosis, and renal toxicity may be indicated. On occasion, close monitoring in an intensive care unit for several days is necessary. If a patient survives the acute intoxication, he or she will usually experience no late sequelae.

Detection in body fluids

Ibuprofen may be quantitated in blood, plasma, or serum to demonstrate the presence of the drug in a person having experienced an anaphylactic reaction, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. A nomogram that relates the ibuprofen plasma concentration, time since ingestion, and risk of developing renal toxicity in overdose patients has been published.[29]

Miscarriage

A Canadian study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal of thousands of pregnant woman suggests that those taking any type or amount of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (including ibuprofen, diclofenac and naproxen) were 2.4 times more likely to miscarry than those not taking the drugs.[30]

Mechanism of action

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen work by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), which converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandin H2 (PGH2). PGH2, in turn, is converted by other enzymes to several other prostaglandins (which are mediators of pain, inflammation, and fever) and to thromboxane A2 (which stimulates platelet aggregation, leading to the formation of blood clots).

Like aspirin, indomethacin, and most other NSAIDs,[citation needed] ibuprofen is considered a nonselective COX inhibitor; that is, it inhibits two isoforms of cyclooxygenase, COX-1 and COX-2. The analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory activity of NSAIDs appears to be achieved mainly through inhibition of COX-2, whereas inhibition of COX-1 would be responsible for unwanted effects on platelet aggregation and the gastrointestinal tract.[31] However, the role of the individual COX isoforms in the analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and gastric damage effects of NSAIDs is uncertain and different compounds cause different degrees of analgesia and gastric damage.[32]

In order to achieve the beneficial effects of ibuprofen and other NSAIDS without gastrointestinal ulceration and bleeding, selective COX-2 inhibitors were developed to inhibit the COX-2 isoform without inhibition of COX-1.[33]

Chemistry

Ibuprofen is only very slightly soluble in water. Less than 1 mg of ibuprofen dissolves in 1 ml water (< 1 mg/mL).[34] However, it is much more soluble in alcohol/water mixtures[citation needed] as well as carbonated water[citation needed]

Stereochemistry

Ibuprofen is produced industrially as a racemate. The compound, like other 2-arylpropionate derivatives (including ketoprofen, flurbiprofen, naproxen, etc.), does contain a stereocenter in the α-position of the propionate moiety. As such, there are two possible enantiomers of ibuprofen, with the potential for different biological effects and metabolism for each enantiomer.

Indeed, the (S)-(+)-ibuprofen (dexibuprofen) was found to be the active form both in vitro and in vivo.

It was logical, then, that there was the potential for improving the selectivity and potency of ibuprofen formulations by marketing ibuprofen as a single-enantiomer product (as occurs with naproxen, another NSAID).

Further in vivo testing, however, revealed the existence of an isomerase (alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase), which converted (R)-ibuprofen to the active (S)-enantiomer.[35][36][37]

|

|

|

|

|

|

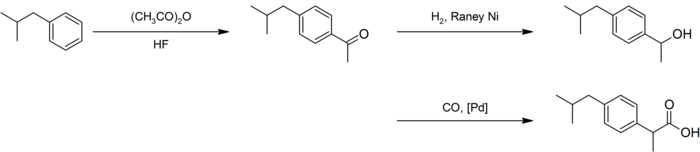

Synthesis

The synthesis of this compound is a popular case study in green chemistry. The original Boots synthesis of ibuprofen consisted of six steps, started with the Friedel-Crafts acetylation of isobutylbenzene. Reaction with ethyl chloroacetate (Darzens reaction) gave the α,β-epoxy ester, which was hydrolyzed and decarboxylated to the aldehyde. Reaction with hydroxylamine gave the oxime, which was converted to the nitrile, then hydrolyzed to the desired acid:[38][39]

An improved synthesis by BHC required only three steps. This improved synthesis won the Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge Greener Synthetic Pathways Award in 1997.[40]

After a similar acetylation, hydrogenation with Raney nickel gave the alcohol, which underwent palladium-catalyzed carbonylation:[38][41]

History

Ibuprofen was derived from propionic acid by the research arm of Boots Group during the 1960s.[42] It was discovered by Andrew RM Dunlop, with colleagues Stewart Adams, John Nicholson, Vonleigh Simmons, Jeff Wilson and Colin Burrows, and was patented in 1961. The drug was launched as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis in the United Kingdom in 1969, and in the United States in 1974. Dr. Adams initially tested his drug on a hangover. He was subsequently awarded an OBE in 1987. Boots was awarded the Queen's Award For Technical Achievement for the development of the drug in 1987.[43]

Availability

Ibuprofen was made available under prescription in the United Kingdom in 1969, and in the United States in 1974.[citation needed] In the years since, the good tolerability profile, along with extensive experience in the population, as well as in so-called Phase IV trials (post-approval studies), has resulted in the availability of ibuprofen over the counter in pharmacies worldwide, as well as in supermarkets and other general retailers.[citation needed]

North America

Ibuprofen is commonly available in the United States up to the FDA's 200 mg 1984 dose limit OTC, higher by prescription.[14]

In Canada, the OTC dose limit is 400 mg.[citation needed]

In 2009, the first injectable formulation of ibuprofen was approved in the United States, under the trade name Caldolor.[44][45] Ibuprofen was the only parenteral for both pain and fever available in the country prior to the approval of Ofirmev (acetaminophen) injection by the FDA.[46]

Research

Ibuprofen is sometimes used for the treatment of acne, because of its anti-inflammatory properties,[47] and has been sold in Japan in topical form for adult acne.[48]

As with other NSAIDs, ibuprofen may be useful in the treatment of severe orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure when standing up).[49]

In some studies, ibuprofen showed superior results compared to a placebo in the prophylaxis of Alzheimer's disease, when given in low doses over a long time.[50] Further studies are needed to confirm the results before ibuprofen can be recommended for this indication.

Ibuprofen has been associated with a lower risk of Parkinson's disease, and may delay or prevent it. Aspirin, other NSAIDs, and paracetamol (acetaminophen) had no effect on the risk for Parkinson's.[51] In March 2011, researchers at Harvard Medical School announced in Neurology that ibuprofen had a neuroprotective effect against the risk of developing Parkinson's disease.[52][53][54] People regularly consuming ibuprofen were reported to have a 38% lower risk of developing Parkinson's disease, but no such effect was found for other pain relievers, such as aspirin and acetaminophen. Use of ibuprofen to lower the risk of Parkinson's disease in the general population would not be problem-free, given the possibility of adverse effects on the urinary and digestive systems.[55] Further research is warranted before recommending ibuprofen for this use.

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 7767417 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 7767417instead. - ^

WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (PDF) (16th ed.). World Health Organization (WHO). 2009. Retrieved 2011-03-30.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children (PDF) (2nd ed.). World Health Organization (WHO). 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-30.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

WHO Model Formulary 2008 (PDF) (2nd ed.). World Health Organization (WHO). 2009. ISBN 978-92-4-154765-9. Retrieved 2011-03-30.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ WHO Model Formulary for Children 2010 (PDF) (2nd ed.). World Health Organization (WHO). 2010. ISBN 978-92-4-159932-0. Retrieved 2011-03-30.

- ^ "PubMed Health - Ibuprofen". U.S. National Library of Medicine. 2010-10-01. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ^ a b "Ibuprofen". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "Neoprofen (ibuprofen lysine) injection. Package insert" (PDF). Ovation Pharmaceuticals.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 14651538 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 14651538instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2777420 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 2777420instead. - ^ a b Rossi, S., ed. (2004). Australian Medicines Handbook (2004 ed.). Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 0-9578521-4-2. OCLC 224121065.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20193831 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 20193831instead. - ^ a b "Ibuprofen". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1531054 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 1531054instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15947398 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15947398instead. - ^ Chan, L. S. (2011). "Bullous Pemphigoid". eMedicine Reference. Medscape.

- ^ "Ibuprofen". Drugs.com.

- ^

"Information for Healthcare Professionals: Concomitant Use of Ibuprofen and Aspirin". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2006-09. Retrieved 2010-11-22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16600768 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 16600768instead. - ^ a b "Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs linked to increased risk of erectile dysfunction". sciencedaily.com. 2011-03-02. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^

Mary Brophy Marcus (March, 2011). "New study links pain relievers to erectile dysfunction". USA Today.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2188537 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 2188537instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 3537613 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 3537613instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12737366 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 12737366instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10696926 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 10696926instead. - ^

Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15214617 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15214617instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 3777588 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 3777588instead. - ^ Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 758–761.

- ^ "Miscarriage risk doubled: drug study". theage.com.au. 2011-09-07. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- ^

Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19203472 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19203472instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18363350 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 18363350instead. - ^ "Pain Medications". eMedicine. 2006-02-13. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- ^ Motrin (Ibuprofen) drug description - FDA-approved labeling for prescription drugs and medications at RxList

- ^

Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1859831 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 1859831instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1352228 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 1352228instead. - ^

Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 9106621 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 9106621instead. - ^ a b "Ibuprofen — a case study in green chemistry" (pdf). Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ^ US patent 3385886, Stuart, N. J. & Sanders, A. S., issued 1968-05-28, assigned to Boots Pure Drug Company

- ^ "Presidential Green Chemistry Challenge: 1997 Greener Synthetic Pathways Award". United States EPA. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1021/ed100892p , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1021/ed100892pinstead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1569234 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 1569234instead. - ^ Lambert, Victoria (2007-10-08). "Dr. Stewart Adams: 'I tested ibuprofen on my hangover'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2008-01-20.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Caldolor (Ibuprofen) NDA #022348". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). March 11, 2010.

- ^ "FDA Approves Injectable Form of Ibuprofen" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 11, 2009.

- ^ "FDA Approves Caldolor: Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Announces FDA Approval of Caldolor" (Press release). Drugs.com. June 11, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-13.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 6239884 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 6239884instead. - ^ "In Japan, an OTC ibuprofen ointment (Fukidia) for alleviating adult acne has been launched". Inpharma. 1 (1530). Adis: 18. March 25, 2006. ISSN 1173-8324.

- ^

Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 7041104 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 7041104instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16195368 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 16195368instead. - ^

Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16240369 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 16240369instead. - ^

Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21368281 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 21368281instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21555992 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 21555992instead. - ^

Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21368280 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 21368280instead. - ^ Mary Brophy Marcus (March 2, 2011). "Ibuprofen may reduce risk of getting Parkinson's disease". USA Today.