Interferon beta-1a

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Avonex, Rebif, Plegridy, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| MedlinePlus | a604005 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous, intramuscular |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 10 hrs |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C908H1408N246O252S7 |

| Molar mass | 20027.14 g·mol−1 |

| | |

Interferon beta-1a (also interferon beta 1-alpha) is a cytokine in the interferon family used to treat multiple sclerosis (MS).[5] It is produced by mammalian cells, while interferon beta-1b is produced in modified E. coli.[6] Some research indicates that interferon injections may result in an 18–38% reduction in the rate of MS relapses.[7]

Interferon beta has not been shown to slow the advance of disability.[8][9][10][11] Interferons are not a cure for MS (there is no known cure); the claim is that interferons may slow the progress of the disease if started early and continued for the duration of the disease.[12]

Medical uses

[edit]Clinically isolated syndrome

[edit]The earliest clinical presentation of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis is the clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), that is, a single attack of a single symptom. During a CIS, there is a subacute attack suggestive of demyelination which should be included in the spectrum of MS phenotypes.[13] Treatment with interferons after an initial attack decreases the risk of developing clinical definite MS.[14][15]

Relapsing-remitting MS

[edit]Medications are modestly effective at decreasing the number of attacks in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis[16] and in reducing the accumulation of brain lesions, which is measured using gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[14] Interferons reduce relapses by approximately 30% and their safe profile make them the first-line treatments.[14] Nevertheless, not all the patients are responsive to these therapies. It is known that 30% of MS patients are non-responsive to Beta interferon.[17] They can be classified in genetic, pharmacological and pathogenetic non-responders.[17] One of the factors related to non-respondance is the presence of high levels of interferon beta neutralizing antibodies. Interferon therapy, and specially interferon beta 1b, induces the production of neutralizing antibodies, usually in the second 6 months of treatment, in 5 to 30% of treated patients.[14] Moreover, a subset of RRMS patients with specially active MS, sometimes called "rapidly worsening MS" are normally non-responders to interferon beta 1a.[18][19]

While more studies of the long-term effects of the drugs are needed,[12][14] existing data on the effects of interferons indicate that early-initiated long-term therapy is safe and it is related to better outcomes.[12]

Side effects

[edit]

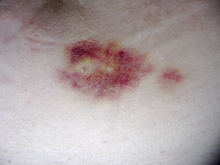

Interferon beta-1a is available only in injectable forms, and can cause skin reactions at the injection site that may include cutaneous necrosis. Skin reactions with interferon beta are more common with subcutaneous administration and vary greatly in their clinical presentation.[20] They usually appear within the first month of treatment albeit their frequence and importance diminish after six months of treatment.[20] Skin reactions are more prevalent in women.[20] Mild skin reactions usually do not impede treatment whereas necroses appear in around 5% of patients and lead to the discontinuation of the therapy.[20] Also over time, a visible dent at the injection site due to the local destruction of fat tissue, known as lipoatrophy, may develop, however, this rarely occurs with interferon treatment.[21]

Interferons, a subclass of cytokines, are produced in the body during illnesses such as influenza in order to help fight the infection. They are responsible for many of the symptoms of influenza infections, including fever, muscle aches, fatigue, and headaches.[22] Many patients report influenza-like symptoms hours after taking interferon beta that usually improve within 24 hours, being such symptoms related to the temporary increase of cytokines.[14][20] This reaction tends to disappear after 3 months of treatment and its symptoms can be treated with over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, that reduce fever and pain.[20] Another common transient secondary effect with interferon-beta is a functional deterioration of already existing symptoms of the disease.[20] Such deterioration is similar to the one produced in MS patients due to heat, fever or stress (Uhthoff's phenomenon), usually appears within 24 hours of treatment, is more common in the initial months of treatment, and may last several days.[20] A symptom specially sensitive to worsening is spasticity.[20] Interferon-beta can also reduce numbers of white blood cells (leukopenia), lymphocytes (lymphopenia) and neutrophils (neutropenia), as well as affect liver function.[20] In most cases these effects are non-dangerous and reversible after cessation or reduction of treatment.[20] Nevertheless, recommendation is that all patients should be monitored through laboratory blood analyses, including liver function tests, to ensure safe use of interferons.[20]

To help prevent injection-site reactions, patients are advised to rotate injection sites and use an aseptic injection technique. Injection devices are available to optimize the injection process. Side effects are often onerous enough that many patients ultimately discontinue taking interferons [citation needed] (or glatiramer acetate, a comparable disease-modifying therapy requiring regular injections).

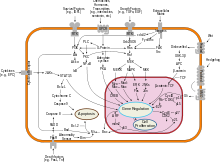

Mechanism of action

[edit]Interferon beta balances the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory agents in the brain, and reduces the number of inflammatory cells that cross the blood brain barrier.[23] Overall, therapy with interferon beta leads to a reduction of neuron inflammation.[23] Moreover, it is also thought to increase the production of nerve growth factor and consequently improve neuronal survival.[23] In vitro, interferon beta reduces production of Th17 cells which are a subset of T lymphocytes believed to have a role in the pathophysiology of MS.[24]

Society and culture

[edit]Brand names

[edit]Avonex

[edit]Avonex was approved in the US in 1996,[25] and in the European Union in 1997, and is registered in more than 80 countries worldwide.[citation needed] It is the leading MS therapy in the US, with around 40% of the overall market, and in the European Union, with around 30% of the overall market.[citation needed] It is produced by the Biogen biotechnology company, originally under competition protection in the US under the Orphan Drug Act.

Avonex is sold in three formulations, a lyophilized powder requiring reconstitution, a pre-mixed liquid syringe kit, and a pen; it is administered via intramuscular injection.[1]

Rebif

[edit]Rebif is a disease-modifying drug (DMD) used to treat multiple sclerosis in cases of clinically isolated syndromes as well as relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis and is similar to the interferon beta protein produced by the human body. It is co-marketed by Merck Serono and Pfizer in the US under an exception to the Orphan Drug Act. [citation needed] It was approved in the European Union in 1998, and in the US in 2002; it has since been approved in more than 90 countries worldwide including Canada and Australia.[citation needed] EMD Serono has had sole rights to Rebif in the US since January 2016.[26][27] Rebif is administered via subcutaneous injection.[2]

Cinnovex

[edit]Cinnovex is the brand name of recombinant Interferon beta-1a, which is manufactured as biosimilar/biogeneric in Iran. It is produced in a lyophilized form and sold with distilled water for injection. Cinnovex was developed at the Fraunhofer Society in collaboration with CinnaGen, and is the first therapeutic protein from a Fraunhofer laboratory to be approved as biogeneric / biosimilar medicine. There are several clinical studies to prove the similarity of CinnoVex and Avonex.[28] A more water-soluble variant is currently being investigated by the Vakzine Projekt Management (VPM) GmbH in Braunschweig, Germany.

Plegridy

[edit]Plegridy is a brand name of a pegylated form of Interferon beta-1a. Plegridy's advantage is it only needs injecting once every two weeks.[29]

Betaferon (interferon beta-1b)

[edit]Closely related to interferon beta-1a is interferon beta-1b, which is also indicated for MS, but is formulated with a different dose and administered with a different frequency. Each drug has a different safety/efficacy profile.[30] Interferon beta-1b is marketed only by Bayer in the US as Betaseron, and outside the US as Betaferon.

Economics

[edit]In the United States, as of 2015[update], the cost is between US$1,284 and US$1,386 per 30 mcg vial.[31] As of 2020, the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC) in the United States for Avonex was $6,872.94 for a 30 mcg kit.[32]

Avonex and Rebif are on the top ten best-selling multiple sclerosis drugs of 2013.[33]

It is an example of a specialty drug that would only be available through a specialty pharmacy. This is because it requires a refrigerated chain of distribution and costs $17,000 a year.[34]

| No. | 2013 Global Sales | INN | Brand names | Companies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $4.33 billion | Glatiramer acetate | Copaxone | Teva |

| 2 | $3.00 billion | Interferon beta 1a | Avonex | Biogen Idec |

| 3 | $2.51 billion | Interferon beta 1a | Rebif | Merck KGaA |

| 4 | $1.93 billion | Fingolimod | Gilenya | Novartis |

| 5 | $1.41 billion | Natalizumab | Tysabri | Biogen Idec |

| 6 | $1.38 billion | Interferon beta 1b | Betaseron/Betaferon | Bayer HealthCare |

| 7 | $876 million | Dimethyl fumarate | Tecfidera | Biogen Idec |

| 8 | $303 million | 4-Aminopyridine | Ampyra | Acorda Therapeutics |

| 9 | $250 million | Adrenocorticotropic hormone | H.P. Acthar Gel | Questcor Pharmaceuticals |

| 10 | $221 million | Teriflunomide | Aubagio | Sanofi |

Research

[edit]COVID-19

[edit]Interferon beta-1a administered subcutaneously or intravenously was investigated since March 2020 as a potential treatment in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in a multinational Solidarity trial (initially in combination with lopinavir) but it did not reduce in-hospital mortality compared to local standard of care.[35]

SNG001, an inhalation formulation of interferon beta-1a, is being developed as a treatment for COVID-19 by Synairgen.[36][37] A pilot trial in hospitalized patients showed higher odds of clinical improvement with SNG001 compared to placebo[38] and in January 2021 a phase 3 trial in this population started.[39]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Avonex- interferon beta-1a kit Avonex Pen- interferon beta-1a injection, solution Avonex- interferon beta-1a injection, solution". DailyMed. 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Rebif- interferon beta-1a kit Rebif Rebidose- interferon beta-1a kit Rebif- interferon beta-1a injection, solution Rebif- interferon beta-1a injection, solution Rebif Rebidose- interferon beta-1a injection, solution". DailyMed. 5 June 2020. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Avonex EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "Rebif EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Murdoch D, Lyseng-Williamson KA (2005). "Spotlight on subcutaneous recombinant interferon-beta-1a (Rebif) in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis". BioDrugs. 19 (5): 323–325. doi:10.2165/00063030-200519050-00005. PMID 16207073. S2CID 3122427.

- ^ Giovannoni G, Munschauer FE, Deisenhammer F (November 2002). "Neutralising antibodies to interferon beta during the treatment of multiple sclerosis". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 73 (5): 465–469. doi:10.1136/jnnp.73.5.465. PMC 1738139. PMID 12397132.

- ^ Stachowiak J (2008). "Is Avonex Right for You?". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-05-07.

- ^ Shirani A, Zhao Y, Karim ME, Evans C, Kingwell E, van der Kop ML, et al. (July 2012). "Association between use of interferon beta and progression of disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis". JAMA. 308 (3): 247–256. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.7625. PMID 22797642.

- ^ Kappos L, Kuhle J, Multanen J, Kremenchutzky M, Verdun di Cantogno E, Cornelisse P, et al. (November 2015). "Factors influencing long-term outcomes in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: PRISMS-15". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 86 (11): 1202–1207. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2014-310024. PMC 4680156. PMID 26374702.

- ^ Calabresi PA, Kieseier BC, Arnold DL, Balcer LJ, Boyko A, Pelletier J, et al. (July 2014). "Pegylated interferon β-1a for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (ADVANCE): a randomised, phase 3, double-blind study". The Lancet. Neurology. 13 (7): 657–665. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70068-7. PMID 24794721. S2CID 45183415.

- ^ Jacobs LD, Cookfair DL, Rudick RA, Herndon RM, Richert JR, Salazar AM, et al. (March 1996). "Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG)". Annals of Neurology. 39 (3): 285–294. doi:10.1002/ana.410390304. PMID 8602746. S2CID 24663294.

- ^ a b c Freedman MS (January 2011). "Long-term follow-up of clinical trials of multiple sclerosis therapies". Neurology. 76 (1 Suppl 1): S26 – S34. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318205051d. PMID 21205679. S2CID 16929304.

- ^ Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, Cutter GR, Sørensen PS, Thompson AJ, et al. (July 2014). "Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions". Neurology. 83 (3): 278–286. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000560. PMC 4117366. PMID 24871874.

- ^ a b c d e f Compston A, Coles A (October 2008). "Multiple sclerosis". Lancet. 372 (9648): 1502–1517. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7. PMID 18970977. S2CID 195686659.

- ^ Bates D (January 2011). "Treatment effects of immunomodulatory therapies at different stages of multiple sclerosis in short-term trials". Neurology. 76 (1 Suppl 1): S14 – S25. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182050388. PMID 21205678. S2CID 362182.

- ^ Rice GP, Incorvaia B, Munari L, Ebers G, Polman C, D'Amico R, Filippini G (2001). "Interferon in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001 (4): CD002002. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002002. PMC 7017973. PMID 11687131.

- ^ a b Bertolotto A, Gilli F (September 2008). "Interferon-beta responders and non-responders. A biological approach". Neurological Sciences. 29 (Suppl 2): S216 – S217. doi:10.1007/s10072-008-0941-2. PMID 18690496. S2CID 19618597.

- ^ Buttinelli C, Clemenzi A, Borriello G, Denaro F, Pozzilli C, Fieschi C (November 2007). "Mitoxantrone treatment in multiple sclerosis: a 5-year clinical and MRI follow-up". European Journal of Neurology. 14 (11): 1281–1287. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01969.x. PMID 17956449. S2CID 36392563.

- ^ Boster A, Edan G, Frohman E, Javed A, Stuve O, Tselis A, et al. (February 2008). "Intense immunosuppression in patients with rapidly worsening multiple sclerosis: treatment guidelines for the clinician". The Lancet. Neurology. 7 (2): 173–183. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70020-6. PMID 18207115. S2CID 40367120.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Walther EU, Hohlfeld R (November 1999). "Multiple sclerosis: side effects of interferon beta therapy and their management". Neurology. 53 (8): 1622–1627. doi:10.1212/wnl.53.8.1622. PMID 10563602. S2CID 30330292.

- ^ Edgar CM, Brunet DG, Fenton P, McBride EV, Green P (February 2004). "Lipoatrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis on glatiramer acetate". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques. 31 (1): 58–63. doi:10.1017/s0317167100002845. PMID 15038472.

- ^ Eccles R (November 2005). "Understanding the symptoms of the common cold and influenza". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 5 (11): 718–725. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70270-X. PMC 7185637. PMID 16253889.

- ^ a b c Kieseier BC (June 2011). "The mechanism of action of interferon-β in relapsing multiple sclerosis". CNS Drugs. 25 (6): 491–502. doi:10.2165/11591110-000000000-00000. PMID 21649449. S2CID 25516515.

- ^ Mitsdoerffer M, Kuchroo V (May 2009). "New pieces in the puzzle: how does interferon-beta really work in multiple sclerosis?". Annals of Neurology. 65 (5): 487–488. doi:10.1002/ana.21722. PMID 19479722. S2CID 42050086.

- ^ "F.D.A. Approves a Biogen Drug for Treating Multiple Sclerosis". The New York Times. 8 May 1996. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ "Neurology & Immunology". EMD Group. Archived from the original on 2024-04-07. Retrieved 2021-08-08.

- ^ "EMD Serono Takes on Exclusive Promotion of Rebif (interferon beta-1a) in the US" (Press release). EMD Serono. Archived from the original on 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2021-08-08 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ Nafissi S, Azimi A, Amini-Harandi A, Salami S, shahkarami MA, Heshmat R (September 2012). "Comparing efficacy and side effects of a weekly intramuscular biogeneric/biosimilar interferon beta-1a with Avonex in relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis: a double blind randomized clinical trial". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 114 (7): 986–989. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.02.039. PMID 22429566. S2CID 9236986.

- ^ "Plegridy- peginterferon beta-1a kit Plegridy Pen- peginterferon beta-1a kit Plegridy- peginterferon beta-1a injection, solution". DailyMed. 19 July 2019. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Abdollahi M (October 2010). "A meta-analysis of the efficacy and tolerability of interferon-β in multiple sclerosis, overall and by drug and disease type". Clinical Therapeutics. 32 (11): 1871–1888. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.10.006. PMID 21095482.

- ^ Langreth R (June 29, 2016). "Decoding Big Pharma's Secret Drug Pricing Practices". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "NADAC as of 2020-02-12". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 2020-02-18. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ^ "The top 10 best-selling multiple sclerosis drugs of 2013". FiercePharma. 9 September 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2024. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Gleason PP, Alexander GC, Starner CI, Ritter ST, Van Houten HK, Gunderson BW, Shah ND (September 2013). "Health plan utilization and costs of specialty drugs within 4 chronic conditions". Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 19 (7): 542–548. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.7.542. PMC 10437312. PMID 23964615.

- ^ Pan H, Peto R, Henao-Restrepo AM, Preziosi MP, Sathiyamoorthy V, Abdool Karim Q, et al. (February 2021). "Repurposed Antiviral Drugs for Covid-19 - Interim WHO Solidarity Trial Results". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (6): 497–511. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2023184. PMC 7727327. PMID 33264556.

- ^ "COVID Trial at Home - developed by Synairgen". Covid Trial at Home - developed by Synairgen. Archived from the original on 2022-05-07. Retrieved 2021-08-08.

- ^ "University-led COVID19 drug trial expands into home testing". medicalxpress. Archived from the original on 2020-06-06. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- ^ Monk PD, Marsden RJ, Tear VJ, Brookes J, Batten TN, Mankowski M, et al. (February 2021). "Safety and efficacy of inhaled nebulised interferon beta-1a (SNG001) for treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial". The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine. 9 (2): 196–206. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30511-7. PMC 7836724. PMID 33189161.

- ^ "Synairgen begins large-scale trial of inhaled COVID-19 treatment". PharmaTimes. 13 January 2021. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

External links

[edit]- "Interferon beta-1a". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Interferon Beta-1a Intramuscular Injection". MedlinePlus.