Umbilical artery

| Umbilical artery | |

|---|---|

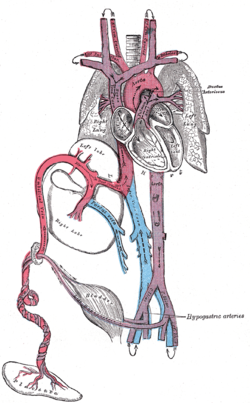

Fetal circulation; the umbilical vein is the large, red vessel at the far left. The umbilical arteries are purple and wrap around the umbilical vein. | |

Scheme of placental circulation. | |

| Details | |

| Source | Internal iliac artery |

| Branches | Superior vesical artery artery of the ductus deferens |

| Vein | Umbilical vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | arteria umbilicalis |

| MeSH | D014469 |

| TA98 | A12.2.15.020 |

| TA2 | 4316 |

| TE | artery_by_E6.0.1.3.0.0.4 E6.0.1.3.0.0.4 |

| FMA | 18820 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The umbilical artery is a paired artery (with one for each half of the body) that is found in the abdominal and pelvic regions. In the fetus, it extends into the umbilical cord.

Structure

[edit]Development

[edit]The umbilical arteries supply deoxygenated blood from the fetus to the placenta. Although this blood is typically referred to as deoxygenated, this blood is fetal systemic arterial blood and will have the same amount of oxygen and nutrients as blood distributed to the other fetal tissues. There are usually two umbilical arteries present together with one umbilical vein in the umbilical cord. The umbilical arteries surround the urinary bladder and then carry all the deoxygenated blood out of the fetus through the umbilical cord. Inside the placenta, the umbilical arteries connect with each other at a distance of approximately 5 mm from the cord insertion in what is called the Hyrtl anastomosis.[1] Subsequently, they branch into chorionic arteries or intraplacental fetal arteries.[2]

The umbilical arteries are actually the anterior division of the internal iliac arteries, and retain part of this function after birth.[3]

The umbilical arteries are one of two arteries in the human body, that carry deoxygenated blood, the other being the pulmonary arteries.

The pressure inside the umbilical artery is approximately 50 mmHg.[4] Resistance to blood flow decreases during development as the artery grows wider.[5]

After development

[edit]The umbilical artery regresses after birth. A portion obliterates to become the medial umbilical ligament (not to be confused with the median umbilical ligament, a different structure that represents the remnant of the embryonic urachus). A portion remains open as a branch of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery. The umbilical artery is found in the pelvis, and gives rise to the superior vesical arteries. In males, it may also give rise to the artery to the ductus deferens which can be supplied by the inferior vesical artery in some individuals.

Clinical significance

[edit]A catheter may be inserted into one of the umbilical arteries of critically ill babies for drawing blood for testing.[6] This is a common procedure in neonatal intensive care, and can often be performed until 2 weeks after birth (when the arteries start to decay too much).[7] The umbilical arteries are typically not suitable for infusions.[6][8]

Additional images

[edit]-

Model of human embryo, 1.3 mm. long.

-

Transverse section of human embryo, eight and a half to nine weeks old.

-

Tail end of human embryo, twenty-five to twenty-nine days old.

-

Inguinal fossae

-

Umbilical artery. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Umbilical artery. Deep dissection. Serial cross-section.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gordon, Z.; Elad, D.; Almog, R.; Hazan, Y.; Jaffa, A. J.; Eytan, O. (2007). "Anthropometry of fetal vasculature in the chorionic plate". Journal of Anatomy. 211 (6): 698–706. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00819.x. PMC 2375851. PMID 17973911.

- ^ Hsieh, FJ; Kuo, PL; Ko, TM; Chang, FM; Chen, HY (1991). "Doppler velocimetry of intraplacental fetal arteries". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 77 (3): 478–82. PMID 1992421.

- ^ Adamson, S. Lee; Myatt, Leslie; Byrne, Bridgette M. P. (2004-01-01), Polin, Richard A.; Fox, William W.; Abman, Steven H. (eds.), "Chapter 72 - Regulation of Umbilical Blood Flow", Fetal and Neonatal Physiology (Third Edition), W.B. Saunders, pp. 748–758, doi:10.1016/b978-0-7216-9654-6.50075-8, ISBN 978-0-7216-9654-6, retrieved 2020-11-16

- ^ Fetal and maternal blood circulation systems From Online course in embryology for medicine students. Universities of Fribourg, Lausanne and Bern (Switzerland). Retrieved on 6 April 2009

- ^ Geipel, Annegret; Gembruch, Ulrich (2009-01-01), Wladimiroff, Juriy W; Eik-Nes, Sturla H (eds.), "Chapter 11 - Evaluation of fetal and uteroplacental blood flow", Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Edinburgh: Elsevier, pp. 209–227, doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-51829-3.00011-8, ISBN 978-0-444-51829-3, retrieved 2020-11-16

- ^ a b Bell, Edward F. (2011-01-01), Goldsmith, Jay P.; Karotkin, Edward H. (eds.), "27 - Nutritional Support", Assisted Ventilation of the Neonate (Fifth Edition), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, pp. 466–483, doi:10.1016/b978-1-4160-5624-9.00027-5, ISBN 978-1-4160-5624-9, retrieved 2020-11-16

- ^ Durand, DAVID J.; Phillips, BARRY; Boloker, JUDD (2003-01-01), Goldsmith, Jay P.; Karotkin, Edward H.; Siede, Barbara L. (eds.), "Chapter 17 - BLOOD GASES: Technical Aspects and Interpretation", Assisted Ventilation of the Neonate (Fourth Edition), W.B. Saunders, pp. 279–292, doi:10.1016/b978-0-7216-9296-8.50022-2, ISBN 978-0-7216-9296-8, retrieved 2020-11-16

- ^ Wald, Samuel H.; Mendoza, Julianne; Mihm, Frederick G.; Coté, Charles J. (2019-01-01), Coté, Charles J.; Lerman, Jerrold; Anderson, Brian J. (eds.), "49 - Procedures for Vascular Access", A Practice of Anesthesia for Infants and Children (Sixth Edition), Philadelphia: Elsevier, pp. 1129–1145.e5, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-42974-0.00049-5, ISBN 978-0-323-42974-0, S2CID 81592410, retrieved 2020-11-16

External links

[edit]- Anatomy photo:43:13-0203 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Female Pelvis: Branches of Internal Iliac Artery"