Hyperthyroidism: Difference between revisions

restore infobox |

|||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

==Veterinary medicine== |

==Veterinary medicine== |

||

====Cats==== |

====Cats==== |

||

In veterinary medicine, ''hyperthyroidism'' is one of the most common endocrine conditions affecting older domesticated cats. Some veterinarians estimate that it occurs in up to 2% of cats over the age of 10.<ref>http://www.thyroid-info.com/articles/cat-hyper.htm</ref> The disease has become significantly more common since the first reports of feline |

In veterinary medicine, ''hyperthyroidism'' is one of the most common endocrine conditions affecting older domesticated cats. Some veterinarians estimate that it occurs in up to 2% of cats over the age of 10.<ref>http://www.thyroid-info.com/articles/cat-hyper.htm</ref> The disease has become significantly more common since the first reports of feline hypgrjfgjderthyroidism in the 1970s. In cats, one cause of hyperthyroidism tends to be benign tumors, but the reason those cats develop such tumors continues to be researched. |

||

However, recent research published in Environmental Science & Technology, a publication of the American Chemical Society, suggests that many cases of feline hyperthyroidism are associated with exposure to environmental contaminants called [[polybrominated diphenyl ethers]] (PBDEs), which are present in flame retardants in many household products, particularly furniture and some electronic products. |

However, recent research published in Environmental Science & Technology, a publication of the American Chemical Society, suggests that many cases of feline hyperthyroidism are associated with exposure to environmental contaminants called [[polybrominated diphenyl ethers]] (PBDEs), which are present in flame retardants in many household products, particularly furniture and some electronic products. |

||

Revision as of 03:30, 24 February 2009

| Hyperthyroidism | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

Hyperthyroidism is the term for overactive tissue within the thyroid gland, resulting in overproduction and thus an excess of circulating free thyroid hormones: thyroxine (T4), triiodothyronine (T3), or both. Thyroid hormone is important at a cellular level, affecting nearly every type of tissue in the body.

Thyroid hormone functions as a stimulus to metabolism, and is critical to normal function of the cell. In excess, it both overstimulates metabolism and exacerbates the effect of the sympathetic nervous system, causing "speeding up" of various body systems, and symptoms resembling an overdose of epinephrine (adrenalin). These include fast heart beat and symptoms of palpitations; nervous system tremor and anxiety symptoms; digestive system hypermotility (diarrhea), and weight loss.

Lack of functioning thyroid tissue results in a symptomatic lack of thyroid hormone, termed hypothyroidism.

Causes

Functional thyroid tissue producing an excess of thyroid hormone occurs in a number of clinical conditions.

The major causes in humans are:

- Graves' disease (the most common etiology with 70-80%)

- Toxic thyroid adenoma

- Toxic multinodular goitre

High blood levels of thyroid hormones (most accurately termed hyperthyroxinemia) can occur for a number of other reasons:

- Inflammation of the thyroid is called thyroiditis. There are a number of different kinds of thyroiditis including Hashimoto's (immune mediated), and subacute (DeQuervain's). These may be initially associated with secretion of excess thyroid hormone, but usually progress to gland dysfunction and thus, to hormone deficiency and hypothyroidism.

- Oral consumption of excess thyroid hormone tablets is possible, as is the rare event of consumption of ground beef contaminated with thyroid tissue, and thus thyroid hormone (termed "hamburger hyperthyroidism").

- Amiodarone, an anti-arrhythmic drug is structurally similar to thyroxine and may cause both under- or overactivity of the thyroid.

- Postpartum thyroiditis (PPT) occurs in about 7% of women during the year after they give birth. PPT typically has several phases, the first of which is hyperthyroidism. This form of hyperthyroidism usually corrects itself within weeks or months without the need for treatment.

Signs and symptoms

Major clinical signs include weight loss (often accompanied by an increased appetite), anxiety, intolerance to heat, fatigue, hair loss, weakness, hyperactivity, irritability, apathy, depression, polyuria, polydipsia, delirium, and sweating. Additionally, patients may present with a variety of symptoms such as palpitations and arrhythmias (notably atrial fibrillation), shortness of breath (dyspnea), loss of libido, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Long term untreated hyperthyroidism can lead to osteoporosis. In the elderly, these classical symptoms may not be present.

Neurological manifestations can include tremors, chorea, myopathy, and in some susceptible individuals (particularly of asian descent) periodic paralysis. An association between thyroid disease and myasthenia gravis has been recognized. The thyroid disease, in this condition, is autoimmune in nature and approximately 5% of patients with myasthenia gravis also have hyperthyroidism. Myasthenia gravis rarely improves after thyroid treatment and the relationship between the two entities is not well understood. Some very rare neurological manifestations that are dubiously associated with thyrotoxicosis are pseudotumor cerebri, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and a Guillain-Barré-like syndrome.

Minor ocular (eye) signs, which may be present in any type of hyperthyroidism, are eyelid retraction ("stare") and lid-lag. In hyperthyroid stare (Dalrymple sign) the eyelids are retracted upward more than normal (the normal position is at the superior corneoscleral limbus, where the "white" of the eye begins at the upper border of the iris). In lid-lag (von Graefe's sign), when the patient tracks an object downward with their eyes, the eyelid fails to follow the downward moving iris, and the same type of upper globe exposure which is seen with lid retraction occurs, temporarily. These signs disappear with treatment of the hyperthyroidism.

Neither of these ocular signs should be confused with exophthalmos (protrusion of the eyeball) which occurs specifically and uniquely in Graves' disease. This forward protrusion of the eyes is due to immune mediated inflammation in the retro-orbital (eye socket) fat. Exophthalmos, when present, may exacerbate hyperthyroid lid-lag and stare.[1]

Thyrotoxic crisis is a rare but severe complication of hyperthyroidism, which may occur when a thyrotoxic patient becomes very sick or physically stressed. Its symptoms can include: an increase in body temperature to over 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit), tachycardia, arrhythmia, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, coma and death.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis may be suspected on history and physical examination, and is confirmed with blood tests.

Measuring the level of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in the blood is usually all that is required. A low TSH indicates that the pituitary gland is being inhibited by increased levels of T4 and/or T3 in the blood, and is therefore a reliable marker of hyperthyroidism. Rarely, a low TSH indicates primary failure of the pituitary, or temporary inhibition of the pituitary due to another illness (euthyroid sick syndrome) and so checking the T4 and T3 is still clinically useful.

Measuring specific antibodies, such as anti-TSH-receptor antibodies in Graves' disease, or anti-thyroid-peroxidase in Hashimoto's thyroiditis, may also contribute to the diagnosis.

Thyroid scintigraphy is a useful test to distinguish between causes of hyperthyroidism, and this entity from thyroiditis.

In addition to testing the TSH levels, many doctors test for T3, Free T3, T4 and/or Free T4 for more detailed results.

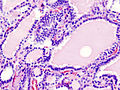

Often hyperthyroidism causes nodules in the thyroid. FNA Biopsy (Fine Needle Aspiration), Ultrasound testing and other radioactive scans can be done to determine whether these nodules are cancerous or not.

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2008) |

Treatment

The major and generally accepted modalities for treatment of hyperthyroidism in humans involve initial temporary use of suppressive thyrostatics medication, and possibly later use of permanent surgical or radioisotope therapy. All approaches may cause under active thyroid function (hypothyroidism) which is easily managed with levothyroxine supplementation.

Temporary medical therapy

Thyrostatics

Thyrostatics are drugs that inhibit the production of thyroid hormones, such as carbimazole (used in UK) and methimazole (used in US), and propylthiouracil. Thyrostatics are believed to work by inhibiting the iodination of thyroglobulin by thyroperoxidase, and thus, the formation of tetra-iodothyronine (T4). Propylthiouracil also works outside the thyroid gland, preventing conversion of (mostly inactive) T4 to the active form T3. Because thyroid tissue usually contains a substantial reserve of thyroid hormone, thyrostatics can take weeks to become effective, and the dose often needs to be carefully titrated over a period of months.

A very high dose is often needed early in treatment, but if too high a dose is used persistently, patients can develop symptoms of hypothyroidism.

Beta-blockers

Many of the common symptoms of hyperthyroidism such as palpitations, trembling, and anxiety are mediated by increases in beta adrenergic receptors on cell surfaces. Beta blockers are a class of drug which offset this effect, reducing rapid pulse associated with the sensation of palpitations, and decreasing tremor and anxiety. This doesn't help the underlying problem of excess thyroid hormone, but makes the symptoms much more manageable, particularly as definitive treatment with thryostatic drugs can take a number of months to work. Propranolol in the UK, and Metoprolol in the US, are most frequently used to augment treatment for hyperthyroid patients.

Permanent treatments

Surgery as an option predates the use of the less invasive radioisotope therapy, but is still required in cases where the thyroid gland is enlarged and causing compression to the neck structures, or the underlying cause of the hyperthyroidism may be cancerous in origin.

Surgery

Surgery (to remove the whole thyroid or a part of it) is not extensively used because most common forms of hyperthyroidism are quite effectively treated by the radioactive iodine method. However, some Graves' disease patients who cannot tolerate medicines for one reason or another, patients who are allergic to iodine, or patients who refuse radioiodine opt for surgical intervention. Also, some surgeons believe that radioiodine treatment is unsafe in patients with unusually large gland, or those whose eyes have begun to bulge from their sockets, claiming that the massive dose of iodine needed will only exacerbate the patient's symptoms. The procedure is quite safe - some surgeons even perform partial thyroidectomies on an out-patient basis.

Radioiodine

In iodine-131 (Radioiodine) radioisotope therapy, radioactive iodine-131 is given orally (either by pill or liquid) on a one-time basis to destroy the function of a hyperactive gland. Patients who do not respond to the first dose are sometimes given an additional radioactive iodine treatment in a larger dose. The iodine given for ablative treatment is different from the iodine used in a scan. Radioactive iodine is given after a routine iodine scan, and uptake of the iodine is determined to confirm hyperthyroidism. The radioactive iodine is picked up by the active cells in the thyroid and destroys them. Since iodine is only picked up by thyroid cells (and picked up more readily by over-active thyroid cells), the destruction is local, and there are no widespread side effects with this therapy. Radioactive iodine ablation has been safely used for over 50 years, and the only major reasons for not using it are pregnancy and breast-feeding.

A common outcome following radioiodine is a swing to the easily treatable hypothyroidism, and this occurs in 78% of those treated for Graves' thyrotoxicosis and in 40% of those with toxic multinodular goiter or solitary toxic adenoma.[2] Use of higher doses of radioiodine reduces the incidence of treatment failure, with the higher response to treatment consisting mostly of higher rates of hypothyroidism.[3] There is increased sensitivity to radioiodine therapy in thyroids appearing on ultrasound scans as more uniform (hypoechogenic), due to densely packed large cells, with 81% later becoming hypothyroid, compared to just 37% in those with more normal scan appearances (normoechogenic).[4]

Veterinary medicine

Cats

In veterinary medicine, hyperthyroidism is one of the most common endocrine conditions affecting older domesticated cats. Some veterinarians estimate that it occurs in up to 2% of cats over the age of 10.[5] The disease has become significantly more common since the first reports of feline hypgrjfgjderthyroidism in the 1970s. In cats, one cause of hyperthyroidism tends to be benign tumors, but the reason those cats develop such tumors continues to be researched.

However, recent research published in Environmental Science & Technology, a publication of the American Chemical Society, suggests that many cases of feline hyperthyroidism are associated with exposure to environmental contaminants called polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), which are present in flame retardants in many household products, particularly furniture and some electronic products.

The study from which the report was based, was conducted jointly by researchers at the EPA's National Health and Environmental Effects Laboratory and Indiana University. In the study, which involved 23 pet cats with feline hyperthyroidism, PDBE blood levels were three times as high as those in younger, non-hyperthyroid cats. Ideally, PBDE and related endocrine disruptors that seriously damage health would not be present in the blood of any animals or humans.

Most recently, mutations of the thyroid stimulating hormone receptor have been discovered which cause a constitutive activation of the thyroid gland cells. Many other factors may play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease such as goitrogens (isoflavones such as genistein, daidzein and quercertin) and iodine and selenium content in the diet.

The most common presenting symptoms are: rapid weight loss, tachycardia (rapid heart rate), vomiting, diarrhea, increased consumption of fluids (polydipsia) and food, and increased urine production (polyuria). Other symptoms include hyperactivity, possible aggression, heart murmurs, a gallop rhythm, an unkempt appearance, and large, thick nails. About 70% of afflicted cats also have enlarged thyroid glands (goiter).

The same three treatments used with humans are also options in treating feline hyperthyroidism (surgery, radioiodine treatment, and anti-thyroid drugs). Drugs must be given to cats for the remainder of their lives, but may be the least expensive option, especially for very old cats. Radioiodine treatment and surgery often cure hyperthyroidism. Some veterinarians prefer radioiodine treatment over surgery because it does not carry the risks associated with anesthesia. Radioiodine treatment, however, is not available in all areas for cats. The reason is that this treatment requires nuclear radiological expertise and facilities, since the animal's urine is radioactive for several days after the treatment, requiring special inpatient handling and facilities usually for a total of 3 weeks (first week in total isolation and the next two weeks in close confinement).[6] Surgery tends to be done only when just one of the thyroid glands is affected (unilateral disease); however following surgery, the remaining gland may become over-active. As in people, one of the most common complications of the surgery is hypothyroidism.

Dogs

Hyperthyroidism is very rare in dogs (occurring in less than 1 or 2% of dogs), who instead tend to have the opposite problem: hypothyroidism. When hyperthyroidism does appear in dogs, it tends to be due to over-supplementation of the thyroid hormone during treatment for hypothyroidism. Symptoms usually disappear when the dose is adjusted.

Occasionally dogs will have functional carcinoma in the thyroid; more often (about 90% of the time) this is a very aggressive tumor that is invasive and easily metastasizes or spreads to other tissues (esp. the lungs), making prognosis very poor. While surgery is possible, it is often very difficult due to the invasiveness of the mass in surrounding tissue including the arteries, the esophagus, and windpipe. It may only be possible to reduce the size of the mass, thus relieving symptoms and also allowing time for other treatments to work.

If a dog does have a benign functional carcinoma (appears in 10% of the cases), treatment and prognosis is no different from that of the cat. The only real difference is that dogs tend to appear to be asymptomic, with the exception of having an enlarged thyroid gland appearing as a lump on the neck.

See also

- Carbimazole

- Hypothyroidism

- Goitrogen

- Graves' ophthalmopathy

- Graves' disease

- { ( graves disease)}

References

- ^ Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry (2006). "Course-Based Physical Examination - Endocrinology -- Endocrinology Objectives (Thyroid Exam)". Undergraduate Medical Education. University of Alberta. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

- ^ Berglund J, Christensen SB, Dymling JF, Hallengren B (1991). "The incidence of recurrence and hypothyroidism following treatment with antithyroid drugs, surgery or radioiodine in all patients with thyrotoxicosis in Malmö during the period 1970-1974". J. Intern. Med. 229 (5): 435–42. PMID 1710255.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Esfahani AF, Kakhki VR, Fallahi B; et al. (2005). "Comparative evaluation of two fixed doses of 185 and 370 MBq 131I, for the treatment of Graves' disease resistant to antithyroid drugs". Hellenic journal of nuclear medicine. 8 (3): 158–61. PMID 16390021.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Markovic V, Eterovic D (2007). "Thyroid echogenicity predicts outcome of radioiodine therapy in patients with Graves' disease". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92 (9): 3547–52. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0879. PMID 17609305.

- ^ http://www.thyroid-info.com/articles/cat-hyper.htm

- ^ Susan Little (2006). "Feline Hyperthyroidism" (PDF). Winn Feline Foundation. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

Additional images

External links

- For Humans

- Hyperthyroidism - Thyroid Problems

- Ophthalmic Dictionary: Hyperthyroidism

- Radiology Info - The radiology information resource for patients: Radioiodine (I -131) Therapy

- National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Thyroid Section of The Hormone Foundation

- Merck

- Mayo Clinic

- Alternative Health Solutions for Thyroid Autoimmunity

- Elaine Moore Graves' and Autoimmune Disease Education

- For Felines

- Gina Spadafori (1997-01-20). "Hyperthyroidism: A Common Ailment in Older Cats". The Pet Connection. Veterinary Information Network. Retrieved 2007-01-28.

This template is no longer used; please see Template:Endocrine pathology for a suitable replacement