Hydrozoa

| Hydrozoa Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

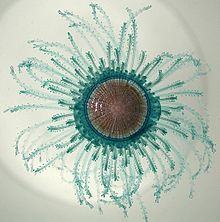

| Siphonophorae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Subphylum: | Medusozoa |

| Class: | Hydrozoa Owen, 1843 |

| Subclasses and orders[1] | |

Hydrozoa (hydrozoans; from Ancient Greek ὕδωρ (húdōr) 'water' and ζῷον (zôion) 'animal') is a taxonomic class of individually very small, predatory animals, some solitary and some colonial, most of which inhabit saline water. The colonies of the colonial species can be large, and in some cases the specialized individual animals cannot survive outside the colony. A few genera within this class live in freshwater habitats. Hydrozoans are related to jellyfish and corals, which also belong to the phylum Cnidaria.

Some examples of hydrozoans are the freshwater jelly (Craspedacusta sowerbyi), freshwater polyps (Hydra), Obelia, Portuguese man o' war (Physalia physalis), chondrophores (Porpitidae), and pink-hearted hydroids (Tubularia).

Anatomy

[edit]Most hydrozoan species include both a polypoid and a medusoid stage in their life cycles, although a number of them have only one or the other. For example, Hydra has no medusoid stage, while Liriope lacks the polypoid stage.[2]

Polyps

[edit]The hydroid form is usually colonial, with multiple polyps connected by tubelike hydrocauli. The hollow cavity in the middle of the polyp extends into the associated hydrocaulus, so that all the individuals of the colony are intimately connected. Where the hydrocaulus runs along the substrate, it forms a horizontal root-like stolon that anchors the colony to the bottom.

The colonies are generally small, no more than a few centimeters across, but some in Siphonophorae can reach sizes of several meters. They may have a tree-like or fan-like appearance, depending on species. The polyps themselves are usually tiny, although some noncolonial species are much larger, reaching 6 to 9 cm (2.4 to 3.5 in), or, in the case of the deep-sea Branchiocerianthus, a remarkable 2 m (6.6 ft).[2]

The hydrocaulus is usually surrounded by a sheath of chitin and proteins called the perisarc. In some species, this extends upwards to also enclose part of the polyps, in some cases including a closeable lid through which the polyp may extend its tentacles.[2]

In any given colony, the majority of polyps are specialized for feeding. These have a more or less cylindrical body with a terminal mouth on a raised protuberance called the hypostome, surrounded by a number of tentacles. The polyp contains a central cavity, in which initial digestion takes place. Partially digested food may then be passed into the hydrocaulus for distribution around the colony and completion of the digestion process. Unlike some other cnidarian groups, the lining of the central cavity lacks stinging nematocysts, which are found only on the tentacles and outer surface.

All colonial hydrozoans also include some polyps specialized for reproduction. These lack tentacles and contain numerous buds from which the medusoid stage of the life cycle is produced. The arrangement and type of these reproductive polyps varies considerably between different groups.

In addition to these two basic types of polyps, a few colonial species have other specialized forms. In some, defensive polyps are found, armed with large numbers of stinging cells. In others, one polyp may develop as a large float, from which the other polyps hang down, allowing the colony to drift in open water instead of being anchored to a solid surface.[2]

Medusae

[edit]The medusae of hydrozoans are smaller than those of typical jellyfish, ranging from 0.5 to 6 cm (0.20 to 2.36 in) in diameter. Although most hydrozoans have a medusoid stage, this is not always free-living and in many species exists solely as a sexually reproducing bud on the surface of the hydroid colony. Sometimes, these medusoid buds may be so degenerated as to entirely lack tentacles or mouths, essentially consisting of an isolated gonad.[2]

The body consists of a dome-like umbrella ringed by tentacles. A tube-like structure hangs down from the centre of the umbrella and includes the mouth at its tip. Most hydrozoan medusae have just four tentacles, although a number of exceptions exist. Stinging cells are found on the tentacles and around the mouth.

The mouth leads into a central stomach cavity. Four radial canals connect the stomach to an additional, circular canal running around the base of the bell, just above the tentacles. Striated muscle fibres also line the rim of the bell, allowing the animal to move along by alternately contracting and relaxing its body. An additional shelf of tissue lies just inside the rim, narrowing the aperture at the base of the umbrella, and thereby increasing the force of the expelled jet of water.[2]

The nervous system is unusually advanced for cnidarians. Two nerve rings lie close to the margin of the bell, and send fibres into the muscles and tentacles. The genus Sarsia has even been reported to possess organised ganglia. Numerous sense organs are closely associated with the nerve rings. Mostly these are simple sensory nerve endings, but they also include statocysts and primitive light-sensitive ocelli.[2]

Life cycle

[edit]Hydroid colonies are usually dioecious, which means they have separate sexes—all the polyps in each colony are either male or female, but not usually both sexes in the same colony. In some species, the reproductive polyps, known as gonozooids (or "gonotheca" in thecate hydrozoans) bud off asexually produced medusae. These tiny, new medusae (which are either male or female) mature and spawn, releasing gametes freely into the sea in most cases. Zygotes become free-swimming planula larvae or actinula larvae that either settle on a suitable substrate (in the case of planulae), or swim and develop into another medusa or polyp directly (actinulae). Colonial hydrozoans include siphonophore colonies, Hydractinia, Obelia, and many others.[3]

In hydrozoan species with both polyp and medusa generations, the medusa stage is the sexually reproductive phase. Medusae of these species of Hydrozoa are known as "hydromedusae". Most hydromedusae have shorter lifespans than the larger scyphozoan jellyfish. Some species of hydromedusae release gametes shortly after they are themselves released from the hydroids (as in the case of fire corals), living only a few hours, while other species of hydromedusae grow and feed in the plankton for months, spawning daily for many days before their supply of food or other water conditions deteriorate and cause their demise.

Additionally, some hydrozoan species (particularly in Turritopsis genus) share an unusual life cycle among the animals - they can transform themselves from sexually mature medusae stage back to their juvenile hydroid stage.[4]

Systematics and evolution

[edit]

The earliest hydrozoans may be from the Vendian (late Precambrian), more than 540 million years ago.[5]

Hydrozoan systematics are highly complex.[6] Several approaches for expressing their interrelationships were proposed and heavily contested since the late 19th century, but in more recent times a consensus seems to be emerging.

Historically, the hydrozoans were divided into a number of orders, according to their mode of growth and reproduction. Most famous among these was probably the assemblage called "Hydroida", but this group is apparently paraphyletic, united by plesiomorphic (ancestral) traits. Other such orders were the Anthoathecatae, Actinulidae, Laingiomedusae, Polypodiozoa, Siphonophorae and Trachylina.

As far as can be told from the molecular and morphological data at hand, the Siphonophora for example were just highly specialized "hydroids," whereas the Limnomedusae—presumed to be a "hydroid" suborder—were simply very primitive hydrozoans and not closely related to the other "hydroids." So, the hydrozoans now are at least tentatively divided into two subclasses, the Leptolinae (containing the bulk of the former "Hydroida" and the Siphonophora) and the Trachylinae, containing the others (including the Limnomedusae). The monophyly of several of the presumed orders in each subclass is still in need of verification.[1]

In any case, according to this classification, the hydrozoans can be subdivided as follows, with taxon names emended to end in "-ae":[1]

Class Hydrozoa

- Subclass Hydroidolina

- Order Anthoathecata (= Anthoathecata(e), Athecata(e), Anthomedusae, Stylasterina(e)) — includes Laingoimedusae but monophyly requires verification

- Order Leptothecata (= Leptothecata(e), Thecaphora(e), Thecata(e), Leptomedusae)

- Order Siphonophorae

- Subclass Trachylinae

- Order Actinulidae

- Order Limnomedusae — monophyly requires verification; tentatively placed here

- Order Narcomedusae

- Order Trachymedusae — monophyly requires verification

ITIS uses the same system, but unlike here, does not use the oldest available names for many groups.

In addition, there exists a cnidarian parasite, Polypodium hydriforme, which lives inside its host's cells. It is sometimes placed in the Hydrozoa, though its relationships are currently unresolved—a somewhat controversial 18S rRNA sequence analysis found it to be closer to the also parasitic Myxozoan. It was traditionally placed in its own class, Polypodiozoa, and this view is often seen to reflect the uncertainties surrounding this highly distinct animal.[7]

Other classifications

[edit]

Some of the more widespread classification systems for the Hydrozoa are listed below. Though they are often found in seemingly authoritative Internet sources and databases, they do not agree with the available data.[citation needed]Especially the presumed phylogenetic distinctness of the Siphonophorae is a major flaw that was corrected only recently. [when?]

The obsolete classification mentioned above was:

- Order Actinulidae

- Order Anthoathecatae

- Order Hydroida

- Suborder Anthomedusae

- Suborder Leptomedusae

- Suborder Limnomedusae

- Order Laingiomedusae

- Order Polypodiozoa

- Order Siphonophorae

- Order Trachylina

- Suborder Narcomedusae

- Suborder Trachymedusae

A very old classification that is sometimes still seen is:

- Order Hydroida

- Order Milleporina

- Order Siphonophorae

- Order Stylasterina (= Anthomedusae)

- Order Trachylinida

Catalogue of Life uses:

- Order Actinulida

- Order Anthoathecata (= Anthomedusae)

- Order Hydroida

- Order Laingiomedusae

- Order Leptothecata (= Leptomedusae)

- Order Limnomedusae

- Order Narcomedusae

- Order Siphonophorae

- Order Trachymedusae

Animal Diversity Web uses:

- Order Actinulida

- Order Anthoathecata

- Order Laingiomedusae

- Order Leptothecata

- Order Limnomedusae

- Order Narcomedusae

- Order Siphonophorae

- Order Trachymedusae

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Schuchert, Peter. "World Hydrozoa Database". Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 122–139. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ Bouillon, J.; Gravili, C.; Pagès, F.; Gili, J.-M.; Boero, F. (2006). An introduction to Hydrozoa. Mémoires du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, 194. Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle: Paris, France. ISBN 2-85653-580-1. 591pp. + 1 cd-rom

- ^ Rich, Nathaniel (2012-11-28). "Can a Jellyfish Unlock the Secret of Immortality?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

- ^ Waggoner, Ben M.; Smith, David. "Hydrozoa: Fossil Record". UCMP Berkeley. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ Boero, Ferdinando; Bouillon, Jean (January 2000). "The hydrozoa: A new classification in the light of old knowledge". researchgate.net. doi:10.1285/I15910725V24P3. S2CID 82373673.

- ^ Zrzavý & Hypša 2003

- Schuchert, Peter (2011). "Hydrozoan Phylogeny and Classification". The Hydrozoa Directory. Natural History Museum of Geneva. Archived from the original on 2013-06-04.

- Zrzavý, Jan & Hypša, Václav (2003): Myxozoa, Polypodium, and the origin of the Bilateria: The phylogenetic position of "Endocnidozoa" in light of the rediscovery of Buddenbrockia. Cladistics 19(2): 164–169. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00305.x (HTML abstract)

External links

[edit]- J. Bouillon; M.D. Medel; F. Pagès; J.M. Gili; F. Boero; C. Gravili (2004). "Fauna of the Mediterranean Hydrozoa" (PDF). Scientia Marina. 68 (2 ed.): 5–438. doi:10.3989/scimar.2004.68s25.

- Les Hydraires à la Réunion et dans l'océan Indien at the Wayback Machine (archived March 15, 2011)

- Bo Johannesson; Martin Larsvik; Lars-Ove Loo; Helena Samuelsson (2000). "The hydroid colony and its life cycle". Aquascope. Tjärnö Marine Biological Laboratory.

- Schuchert, P. (2016). "World Hydrozoa Database".

- Claudia E. Mills (2012-09-07). "Hydromedusae". University of Washington.

- Ben M. Waggoner (1995-07-21). "Introduction to the Hydrozoa". University of California Museum of Paleontology.