History of the aircraft carrier

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2018) |

Aircraft carriers are warships that evolved from balloon-carrying wooden vessels into nuclear-powered vessels carrying many dozens of fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft. Since their introduction they have allowed naval forces to project air power great distances without having to depend on local bases for staging aircraft operations.

Balloon carriers were the first ships to deploy manned aircraft, used during the 19th and early 20th century, mainly for observation purposes. The advent of fixed-wing aircraft in 1903 was followed in 1910 by the first flight from the deck of a US Navy cruiser. Seaplanes and seaplane tender support ships, such as HMS Engadine, followed. The development of flat top vessels produced the first large fleet ships. This evolution was well underway by the early to mid-1920s, resulting in the commissioning of ships such as Hōshō (1922), HMS Hermes (1924),[1] Béarn (1927), and the Lexington-class aircraft carriers (1927).

Most early aircraft carriers were conversions of ships that were laid down (or had even served) as different ship types: cargo ships, cruisers, battlecruisers, or battleships. During the 1920s, several navies started ordering and building aircraft carriers that were specifically designed as such. This allowed the design to be specialized to their future role, and resulted in superior ships. During the Second World War, these ships would become the backbone of the carrier forces of the US, British, and Japanese navies, known as fleet carriers.

World War II saw the first large-scale use of aircraft carriers and induced further refinement of their launch and recovery cycle leading to several design variants. The USA built small escort carriers, such as USS Bogue, as a stop-gap measure to provide air support for convoys and amphibious invasions. Subsequent light aircraft carriers, such as USS Independence, represented a larger, more "militarized" version of the escort carrier concept. Although the light carriers usually carried the same size air groups as escort carriers, they had the advantage of higher speed as they had been converted from cruisers under construction.

Early history - balloon and seaplane carriers

[edit]

The earliest recorded instance of using a ship for airborne operations occurred in 1806, when Lord Cochrane of the Royal Navy launched kites from the 32-gun frigate HMS Pallas in order to drop propaganda leaflets.[2] The proclamations against Napoleon Bonaparte, written in French, were attached to kites, and the kite strings were set alight; when the strings had burned through, the leaflets landed on French soil.[3]

Balloon carriers

[edit]Over 40 years later, on 12 July 1849,[4] the Austrian Navy ship SMS Vulcano was used for launching incendiary balloons. A number of small Montgolfiere hot air ballons were launched with the intention of dropping bombs on Venice. Although the attempt largely failed due to contrary winds which drove the balloons back over the ship, one bomb did land on the city.[5]

Later, during the American Civil War, about the time of the Peninsula Campaign, gas-filled balloons were used to perform reconnaissance on Confederate positions. The battles soon turned inland into the heavily forested areas of the Peninsula, however, where balloons could not travel. A coal barge, USS George Washington Parke Custis, was cleared of all deck rigging to accommodate the gas generators and apparatus of balloons. From the barge Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe, Chief Aeronaut of the Union Army Balloon Corps, made his first ascents over the Potomac River and telegraphed claims of the success of the first aerial venture ever made from a water-borne vessel. Other barges were converted to assist with the other military balloons transported about the eastern waterways, but none of these Civil War craft ever took to the high seas.

Balloons launched from ships led to the development of balloon carriers, or balloon tenders, during World War I, by the navies of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Sweden. About ten such "balloon tenders" were built, their main objective being aerial observation posts. These ships were either decommissioned or converted to seaplane tenders after the war.

Seaplane carriers

[edit]

The invention of the seaplane in March 1910, with the French Fabre Hydravion, led to development of the earliest ship designed as an aircraft carrier, albeit limited to aircraft equipped with floats, in December 1911 with the French Navy Foudre, the first seaplane carrier. Commissioned as a seaplane tender, and carrying seaplanes under hangars on the main deck, from where they were lowered onto the sea with a crane, she participated in tactical exercises in the Mediterranean in 1912. Foudre was further modified in November 1913 with a 10-meter flat deck to launch her seaplanes.[6]

HMS Hermes, temporarily converted as an experimental seaplane carrier in April–May 1913, was also one of the first seaplane carriers, and the first experimental seaplane carrier of the Royal Navy. She was originally laid down as a merchant ship, but was converted on the building stocks to be a seaplane carrier for a few trials in 1913, before being converted again to a cruiser, and back again to a seaplane carrier in 1914. She was sunk by a German submarine in October 1914. The first seaplane tender of the US Navy was the USS Mississippi, converted to that role in December 1913.[7]

In September 1914, during World War I, in the Battle of Tsingtao, the Imperial Japanese Navy seaplane carrier Wakamiya conducted the world's first successful naval-launched air raids.[8][9] It lowered four Maurice Farman seaplanes into the water using its crane. These seaplanes later took off in order to bombard German forces, and were retrieved from the surface afterwards.[10]

On the Western front the first naval air raid occurred on 25 December 1914 when twelve seaplanes from HMS Engadine, Riviera and Empress (cross-channel steamers converted into seaplane carriers) attacked the Zeppelin base at Cuxhaven.[11] The attack was not a complete success, although a German warship was damaged; nevertheless the raid demonstrated in the European theatre the feasibility of attack by ship-borne aircraft and showed the strategic importance of this new weapon.

The Russians also were quite innovative in their use of seaplane carriers in the Black Sea theatre of World War I.[12]

Many cruisers and capital ships of the inter-war years often carried a catapult-launched seaplane for reconnaissance and spotting the fall of shot. Such seaplanes were launched by a catapult and recovered by crane from the water after landing. They were successful even during World War II. There were many notable successes early in the war, such as HMS Warspite's float-equipped Swordfish during the Second Battle of Narvik in 1940, which spotted for the guns of the British warships, helping to sink seven German destroyers, and sank the German submarine U-64 with bombs.[13] The Japanese Nakajima A6M2-N "Rufe" floatplane, was derived from the Zero.

Genesis of the flat-deck carrier

[edit]| "An airplane-carrying vessel is indispensable. These vessels will be constructed on a plan very different from what is currently used. First of all the deck will be cleared of all obstacles. It will be flat, as wide as possible without jeopardizing the nautical lines of the hull, and it will look like a landing field." |

| Clément Ader, L'Aviation Militaire, 1909

(See note[14] for additional quotes.) |

As heavier-than-air aircraft developed in the early 20th century, various navies began to take an interest in their potential use as scouts for their big gun warships. In 1909 the French inventor Clément Ader published in his book L'Aviation Militaire the description of a ship to operate airplanes at sea, with a flat flight deck, an island superstructure, deck elevators and a hangar bay. That year the US Naval Attaché in Paris sent a report on his observations.[15]

A number of experimental flights were made to test the concept. Eugene Ely was the first pilot to launch from a stationary ship in November 1910. He took off from a structure fixed over the forecastle of the US armored cruiser USS Birmingham at Hampton Roads, Virginia and landed nearby on Willoughby Spit after some five minutes in the air.

On 18 January 1911, he became the first pilot to land on a stationary ship. He took off from the Tanforan racetrack and landed on a similar temporary structure on the aft of USS Pennsylvania anchored at the San Francisco waterfront—the improvised braking system of sandbags and ropes led directly to the arrestor hook and wires described below. His aircraft was then turned around and he was able to take off again.

Commander Charles Rumney Samson, Royal Navy, became the first airman to take off from a moving warship, on 9 May 1912. He took off in a Short S.38 from the battleship HMS Hibernia while she steamed at 15 kn (17 mph; 28 km/h) during the Royal Fleet Review at Weymouth, England.[16]

Flat-deck carriers in World War I

[edit]HMS Ark Royal was arguably the first active aircraft carrier, as it carried armed seaplanes for use in combat and military operations. She was originally laid down as a merchant ship, but was converted on the building stocks to be a hybrid airplane/seaplane carrier with a launch platform. Launched on 5 September 1914, she served in the Dardanelles campaign and throughout World War I. The ship proved to be too slow to work with the Grand Fleet and for operations in the North Sea in general, so Ark Royal was ordered to the Mediterranean in mid-January 1915 to support the Gallipoli campaign.[17]

HMS Furious was the first ship to be designed with the same basic features as modern aircraft carriers, as it was the first aircraft carrier to be equipped with a flight deck for airplanes, although its initial flight decks were in two portions and therefore were not continuously full-length with the ship. This ship was rebuilt in 1925 with a full-length flight deck, and served in combat operations during World War II. Since HMS Ark Royal was a seaplane carrier, it had no actual flight deck; the planes that it carried would take off and land on the sea, and would then be hoisted aboard by shipboard cranes.

During World War I the Royal Navy used HMS Furious to experiment with the use of wheeled aircraft on ships. This ship was reconstructed three times between 1915 and 1925: first, while still under construction, it was modified to receive a flight deck on the fore-deck; in 1917 it was reconstructed with separate flight decks fore and aft of the superstructure; then finally, after the war, it was heavily reconstructed with a three-quarter length main flight deck, and a lower-level takeoff-only flight deck on the fore-deck.

On 2 August First attack using an air-launched torpedo, from a Short Type 184 seaplane flown by Flight Commander Charles H. K. Edmonds from seaplane carrier HMS Ben-my-Chree.[18][19]

On 2 August 1917, Squadron Commander E.H. Dunning, Royal Navy, landed his Sopwith Pup aircraft on HMS Furious in Scapa Flow, Orkney, becoming the first man to land a plane on a moving ship.[20] He was killed five days later during another landing on Furious.[20]

Of carrier operations mounted during the war, one of the most successful took place on 19 July 1918 during the Tondern raid, when seven Sopwith Camels launched from HMS Furious attacked the German Zeppelin base at Tondern with two 50 lb (23 kg) bombs each. Several airships and balloons were destroyed, but as the carrier had no method of recovering the aircraft, two of the pilots ditched their aircraft in the sea alongside the carrier while the others headed for neutral Denmark. This was the first ever carrier-launched airstrike.[21]

Inter-war years

[edit]The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 placed strict limits on the tonnages of battleships and battlecruisers for the major naval powers after World War I, as well as not only a limit on the total tonnage for carriers, but also an upper limit of 27000 tons for each ship. Although exceptions were made regarding the maximum ship tonnage, fleet units counted, experimental units did not, the total tonnage could not be exceeded. However, while all of the major navies were over-tonnage on battleships, they were all considerably under-tonnage on aircraft carriers. Consequently, many battleships and battlecruisers under construction (or in service) were converted into aircraft carriers.

HMS Argus: the first full-length flat deck

[edit]

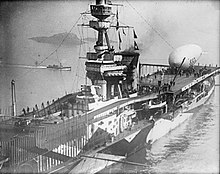

The first ship to have a full-length flat deck was HMS Argus, the conversion of which was completed in September 1918. The United States Navy did not follow suit until 1920, when the conversion of USS Langley, an experimental ship which did not count against America's carrier tonnage, was completed. The first American fleet carriers would not enter service until November 1927 when USS Saratoga of the Lexington-class was commissioned. The lead ship of the class, USS Lexington, was commissioned the following month.

Hōshō: the first purpose-built aircraft carrier commissioned

[edit]

The first purpose-designed aircraft carrier to be laid down was HMS Hermes (1924) in 1918. Japan began work on Hōshō the following year. In December 1922, Hōshō became the first to be commissioned, while Hermes was commissioned in February 1924.[22][23]

HMS Hermes (1924): the first off-set control tower

[edit]

The design of HMS Hermes (1924) preceded and influenced that of Hōshō, and its construction actually began earlier, but numerous tests, experiments and budget considerations delayed its commission. The long gestation of Hermes resulted finally in the first aircraft carrier to display the two most distinctive features of a modern aircraft carrier: the full-length flight deck and the starboard-side control tower island. With the exception of the squared-off flight deck prow and angled flight deck of later carriers, Hermes was the first to display the main features of the classic silhouette and plan layout of the great majority of aircraft carriers produced over the next century.

HMS Hermes (1924) was commissioned two days earlier than a sister aircraft carrier, HMS Eagle. Like Hermes, Eagle had a full-length flight deck and a starboard-side control tower island. Unlike Hermes, however, Eagle was a converted battleship and had a less integrated design and appearance than the purpose-designed Hermes.

Hurricane bow

[edit]A "hurricane bow" is a bow sealed up to the flight deck, first seen on HMS Hermes (1924). The American Lexington-class carriers also featured this when they entered service in 1927. Combat experience proved it to be by far the most useful configuration for the bow of the ship among others that were tried, including an additional flying-off deck and an anti-aircraft battery.[citation needed] The latter was the most common American configuration during World War II, seen in the Essex-class (the "long-hull" variant),[citation needed] and it was not until after the war when a majority of American carriers incorporated the hurricane bow. The first Japanese carrier with a hurricane bow was Taihō.

Important innovations just before and during World War II

[edit]

By the late 1930s, carriers around the world typically carried three types of aircraft: torpedo bombers, also used for conventional bombings and reconnaissance; dive bombers, also used for reconnaissance (in the U.S. Navy, aircraft of this type were known as "scout bombers"); and fighters for fleet defence and bomber escort duties. Because of the restricted space on aircraft carriers, all these aircraft were of small, single-engined types, usually with folding wings to facilitate storage. In the late 1930s, the RN also developed the concept of the armoured flight deck, enclosing the hangar in an armoured box. The lead ship of this new type, HMS Illustrious, was commissioned in 1940.

Light aircraft carriers

[edit]

Prior to the beginning of the war, President Franklin D. Roosevelt noticed that no new aircraft carriers were expected to enter the fleet before 1944, and proposed the conversion of several Cleveland-class cruiser hulls that had already been laid down. They were intended to serve as additional fast carriers, as escort carriers did not have the requisite speed to keep up with the fleet carriers and their escorts. The actual U.S. Navy classification was small aircraft carrier (CVL), not light. Prior to July 1943, they were just classified as aircraft carriers (CV).[24]

The Royal Navy made a similar design which served both Britain and the Commonwealth countries after World War II. One of these carriers, HMS Hermes (1959), was in use as India's INS Viraat, until it was decommissioned in 2017.

Escort carriers and merchant aircraft carriers

[edit]To protect Atlantic convoys, the British developed what they called Merchant Aircraft Carriers, which were merchant ships equipped with a flat deck for six aircraft. These operated with civilian crews, under merchant colors, and carried their normal cargo besides providing air support for the convoy. As there was no lift or hangar, aircraft maintenance was limited and the aircraft spent the entire trip sitting on the deck.

These served as a stop-gap measure until dedicated escort carriers (CVE) could be built in the U.S. About a third of the size of a fleet carrier, they carried between 20 and 30 aircraft, mostly for anti-submarine duties. Over 100 were built or converted from merchantmen. Escort carriers were built in the US from two basic hull designs: one from a merchant ship, and the other from a slightly larger, slightly faster tanker. Besides defending convoys, these were used to transport aircraft across the ocean. Nevertheless, some participated in the battles to liberate the Philippines, notably the Battle off Samar in which six escort carriers and their escorting destroyers aggressively attacked five Japanese battleships and bluffed them into retreating.

Catapult aircraft merchantmen

[edit]As an emergency stop-gap before sufficient merchant aircraft carriers became available, the British provided air cover for convoys using Catapult aircraft merchantman (CAM ships). CAM ships were merchant vessels equipped with an aircraft, usually a battle-weary Hawker Hurricane, launched by a catapult. Once launched, the aircraft could not land back on the deck and had to ditch in the sea if it was not within range of land. In over two years, fewer than 10 launches were ever made, yet these flights did have some success: 6 bombers for the loss of a single pilot.

World War II

[edit]

Aircraft carriers played a significant role in World War II. With seven aircraft carriers afloat, the Royal Navy had a considerable numerical advantage at the start of the war as neither the Germans nor the Italians had carriers of their own.[25] However, the vulnerability of carriers compared to traditional battleships when forced into a gun-range encounter was quickly illustrated by the sinking of HMS Glorious by German battlecruisers during the Norwegian campaign in 1940. The first British warship lost in the war was HMS Courageous sunk by U-29 on 17 September 1939.

The versatility of the carrier was demonstrated in November 1940 when HMS Illustrious launched a long-range strike on the Italian fleet at Taranto signalling the beginning of the effective mobile aircraft strikes, by short-ranged aircraft. This operation incapacitated three of the six battleships in the harbour at a cost of two of the 21 attacking Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers. Carriers also played a major part in reinforcing Malta, both by transporting planes and by defending convoys sent to supply the besieged island. The use of carriers prevented the Italian Navy and land-based German aircraft from dominating the Mediterranean theatre.

In the Atlantic, aircraft from HMS Ark Royal and HMS Victorious were responsible for slowing the German battleship Bismarck during May 1941. Later in the war, escort carriers proved their worth guarding convoys crossing the Atlantic and Arctic oceans.

Germany and Italy also started with the construction or conversion of several aircraft carriers, but with the exception of the nearly finished German Graf Zeppelin and the Italian Aquila, no ship was launched.

World War II in the Pacific Ocean involved clashes between aircraft carrier fleets. Japan started the war with ten aircraft carriers, the largest and most modern carrier fleet in the world at that time. There were seven American aircraft carriers at the beginning of the hostilities, although only three of them were operating in the Pacific.

Drawing on the 1939 Japanese development of shallow-water modifications for aerial torpedoes and the 1940 British aerial attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto, the 1941 Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor was a clear illustration of the power projection capability afforded by a large force of modern carriers. Concentrating six carriers in a single striking unit marked a turning point in naval history, as no other nation had fielded anything comparable.

Meanwhile, the Japanese began their advance through Southeast Asia, and the sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse by Japanese land-based aircraft proved in finality that aircraft, and aircraft carrying warships, would dominate the seas. For the first time in naval history aircraft had sunk a battleship that was maneuvering at sea and fighting back. In April 1942, the Japanese fast carrier strike force ranged into the Indian Ocean and sank shipping, including the damaged and undefended carrier HMS Hermes (1924). Smaller Allied fleets with inadequate aerial protection were forced to retreat or be destroyed. The Doolittle Raid, consisting of 16 B-25 Mitchell medium bombers launched from USS Hornet against Tokyo, forced the recall of the Japanese strike force to home waters. In the Battle of the Coral Sea, the world's first carrier battle[26] and one in which fleets only exchanged blows with aircraft became a tactical victory for the Japanese, but a strategic victory for the allies. For the first time in history, at the Battle of Midway, a naval battle was decisively fought by aircraft and not warships; all four Japanese carriers engaged were sunk by planes from three American carriers (one of which was lost); the battle is considered the turning point of the war in the Pacific. Notably, the battle was orchestrated by the Japanese to draw out American carriers that had proven very elusive and troublesome to the Japanese.

Subsequently, the US were able to build up large numbers of aircraft aboard a mixture of fleet, light and (newly commissioned) escort carriers, primarily with the introduction of the Essex-class in 1943. These ships, around which were built the fast carrier task forces of the 3rd and 5th Fleets, played a major part in winning the Pacific War. The Battle of the Philippine Sea in 1944 was the largest aircraft carrier battle in history and the decisive naval battle of World War II.

The reign of the battleship as the primary component of a fleet finally came to an end when U.S. carrier-borne aircraft sank the largest battleships ever built, the Japanese super battleships Musashi in 1944 and Yamato in 1945. Japan built the largest aircraft carrier of the war: Shinano, which was a Yamato-class ship converted before being halfway completed in order to counter the disastrous loss of four fleet carriers at Midway. She was sunk by the patrolling US submarine Archerfish while in transit shortly after commissioning, but before being fully outfitted or operational, in November 1944.

Wartime emergencies also spurred the creation or conversion of unconventional aircraft carriers. CAM ships, like SS Michael E, were cargo-carrying merchant ships that could launch but not retrieve a single fighter aircraft from a catapult. These vessels were an emergency measure during World War II as were the Merchant aircraft carriers (MACs), such as MV Empire MacAlpine which put a flight deck on top of a cargo ship. Submarine aircraft carriers, such as the French Surcouf and the Japanese I-400-class submarines, which were capable of carrying three Aichi M6A Seiran aircraft, were first built in the 1920s but were generally unsuccessful in combat.

Post-war developments

[edit]

Three major post-war developments came from the need to improve operations of jet-powered aircraft, which had higher weights and landing speeds than their propeller-powered forebears.

The first jet landing on a carrier was made by Lt Cdr Eric 'Winkle' Brown who landed on HMS Ocean in the specially modified de Havilland Vampire registration LZ551/G on 3 December 1945.[27] Brown is also the all-time record holder for the number of carrier landings, at 2,407.[27]

After these successful tests, there were still many misgivings about the suitability of operating jet aircraft routinely from carriers, and LZ551/G was taken to Farnborough to participate in trials of the experimental "rubber deck". Despite significant effort toward developing this idea, and some performance advantages due to the removal of the undercarriage, it was found to be unnecessary; and following the introduction of angled flight decks, jets were operating from carriers by the mid-1950s.[27]

Angled decks

[edit]

During World War II, aircraft would land on the flight deck parallel to the long axis of the ship's hull. Aircraft which had already landed would be parked on the deck at the bow end of the flight deck. A crash barrier was raised behind them to stop any landing aircraft which overshot the landing area because its landing hook missed the arrestor cables. If this happened, it would often cause serious damage or injury and even, if the crash barrier was not strong enough, destruction of parked aircraft.

An important development of the early 1950s was the introduction by the Royal Navy of the angled flight deck by Capt D.R.F. Campbell RN in conjunction with Lewis Boddington of the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough.[27] The runway was canted at an angle of a few degrees from the longitudinal axis of the ship. If an aircraft missed the arrestor cables (referred to as a "bolter"), the pilot only needed to increase engine power to maximum to get airborne again, and would not hit the parked aircraft because the angled deck pointed out over the sea.

The angled flight deck was first tested on HMS Triumph, by painting angled deck markings onto the centerline flight deck for touch and go landings.[28] This was also tested on USS Midway the same year.[29][30] In both tests, the arresting gear and barriers remained oriented to the original axis deck. During September through December 1952 USS Antietam had a rudimentary sponson installed for true angled deck tests, allowing for full arrested landings, which proved during trials to be superior.[29] In 1953 Antietam trained with both US and British naval units, proving the worth of the angled deck concept.[31] HMS Centaur was modified with an overhanging angled flight deck in 1954.[28] The US Navy installed the decks as part of the SCB-125 upgrade for the Essex-class and SCB-110/110A for the Midway-class. In February 1955, HMS Ark Royal became the first carrier to be constructed and launched with the deck, followed in the same year by the lead ships of the British Majestic-class (HMAS Melbourne) and the American Forrestal-class (USS Forrestal).[28]

Steam catapults

[edit]The modern steam-powered catapult, powered by steam from the ship's boilers, was invented by Commander C.C. Mitchell of the Royal Naval Reserve.[27] It was widely adopted following trials on HMS Perseus between 1950 and 1952 which showed it to be more powerful and reliable than the hydraulic catapults which had been introduced in the 1940s.[27]

Optical Landing Systems

[edit]The first of the Optical Landing Systems was another British innovation, the Mirror Landing Aid invented by Lieutenant Commander H. C. N. Goodhart RN.[27] This was a gyroscopically-controlled concave mirror (in later designs replaced by a Fresnel lens Optical Landing System) on the port side of the deck. On either side of the mirror was a line of green "datum" lights. A bright orange "source" light was directed into the mirror creating the "ball" (or "meatball" in later USN parlance), which could be seen by the aviator who was about to land. The position of the ball compared to the datum lights indicated the aircraft's position in relation to the desired glidepath: if the ball was above the datum, the plane was high; below the datum, the plane was low; between the datum, the plane was on glidepath. The gyro stabilisation compensated for much of the movement of the flight deck due to the sea, giving a constant glidepath. The first trials of a mirror landing sight were conducted on HMS Illustrious in 1952.[27] Prior to OLSs, pilots relied on visual flag signals from Landing Signal Officers to help maintain proper glidepath.

Nuclear age

[edit]The US Navy attempted to become a strategic nuclear force in parallel with the United States Air Force (USAF) long-range bombers with the project to build United States. This ship would have carried long range twin-engine bombers, each of which could carry an atomic bomb. The project was canceled under pressure from the newly created United States Air Force. This only delayed the growth of carriers. Nuclear weapons would be part of the carrier weapons load, despite Air Force objections, beginning in 1950 aboard USS Franklin D. Roosevelt and continuing in 1955 aboard USS Forrestal. By the end of the 1950s the Navy had a series of nuclear-armed attack aircraft.

The US Navy also built the first aircraft carrier to be powered by nuclear reactors. USS Enterprise was powered by eight nuclear reactors and was the second surface warship, after USS Long Beach, with nuclear propulsion. Subsequent nuclear supercarriers starting with USS Nimitz took advantage of this technology to increase their endurance utilizing only two reactors. While other nations operate nuclear-powered submarines, thus far only France has a nuclear-powered carrier, Charles de Gaulle.

Helicopters

[edit]

The post-war years also saw the development of the helicopter, with a variety of useful roles and mission capability aboard aircraft carriers. Whereas fixed-wing aircraft are suited to air-to-air combat and air-to-surface attack, helicopters are used to transport equipment and personnel and can be used in an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) role, with dipping sonar, air-launched torpedoes, and depth charges; as well as for anti-surface vessel warfare, with air-launched anti-ship missiles.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the United Kingdom and the United States converted some older carriers into helicopter carriers or Landing Platform Helicopters (LPH); seagoing helicopter bases like HMS Bulwark. To mitigate the expensive connotations of the term "aircraft carrier", the new Invincible-class carriers were originally designated as "through deck cruisers"[citation needed] and were initially to operate as helicopter-only escort carriers. The arrival of the Sea Harrier VTOL/STOVL fast jet meant they could carry fixed-wing aircraft, despite their short flight deck.

The United States used some Essex-class carriers initially as pure anti-submarine warfare (ASW) carriers, embarking helicopters and fixed-wing ASW aircraft like the S-2 Tracker. Later, specialized LPH helicopter carriers for the transport of Marine Corps troops and their helicopter transports were developed. These evolved into the Landing Helicopter Assault (LHA) and later into the Landing Helicopter Dock (LHD) classes of amphibious assault ships, which normally also embark a few Harrier aircraft.

Ski-jump ramp

[edit]

Another British innovation was the ski-jump ramp as an alternative to contemporary catapult systems.[27] The ski-jump ramp at the end of a runway or flight deck allows an aircraft which makes a running start to convert part of its forward momentum into upward motion. The intent is that the additional altitude and upward-angled flight path from the jump provides extra time until the forward airspeed generated by engine thrust is high enough to maintain level flight. STOVL aircraft often also use their ability to direct some of their thrust downwards to give them additional lift until required airspeed is attained.

As the Royal Navy retired or sold the last of its World War II-era carriers, they were replaced with smaller ships designed to operate helicopters and the STOVL Sea Harrier jet. The ski-jump gave the Harriers an enhanced STOVL capability, allowing them to take off with heavier payloads.[32] It was subsequently adopted by the navies of other nations including India, Spain, Italy, Russia, and Thailand.

Post-World War II conflicts

[edit]UN carrier operations in the Korean War

[edit]The United Nations command began carrier operations against the North Korean Army on July 3, 1950, in response to the invasion of South Korea. Task Force 77 consisted at that time of the carriers USS Valley Forge and HMS Triumph. Before the armistice of July 27, 1953, twelve U.S. carriers served 27 tours in the Sea of Japan as part of Task Force 77. During periods of intensive air operations as many as four carriers were on the line at the same time (see Attack on the Sui-ho Dam), but the norm was two on the line with a third "ready" carrier at Yokosuka able to respond to the Sea of Japan at short notice.

A second carrier unit, Task Force 95, served as a blockade force in the Yellow Sea off the west coast of North Korea. The task force consisted of a Commonwealth light carrier (HMS Triumph, Theseus, Glory, Ocean, and HMAS Sydney) and usually a U.S. escort carrier (USS Badoeng Strait, Bairoko, Point Cruz, Rendova, and Sicily).

Over 301,000 carrier sorties were flown during the Korean War: 255,545 by the aircraft of Task Force 77; 25,400 by the Commonwealth aircraft of Task Force 95, and 20,375 by the escort carriers of Task Force 95. United States Navy and Marine Corps carrier-based combat losses were 541 aircraft. The Fleet Air Arm lost 86 aircraft in combat, and the Australian Fleet Air Arm 15.

Post-colonial conflicts

[edit]In the period following World War II through the 1960s, the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands employed their carriers during decolonization conflicts of former colonies.

France employed the carriers Dixmude, La Fayette, Bois Belleau, and Arromanches to conduct operations against the Viet Minh during the 1946–1954 First Indochina War.[33]

The United Kingdom used carrier-based aircraft from HMS Eagle, HMS Albion, and HMS Bulwark, and France from Arromanches and La Fayette, to attack Egyptian positions during the 1956 Suez Crisis. Royal Navy carriers HMS Ocean and Theseus acted as floating bases to ferry troops ashore by helicopter in the first ever large-scale helicopter-borne assault.[34]

The Royal Netherlands Navy deployed HNLMS Karel Doorman and an escorting battle group to Western New Guinea in 1962 to protect it from Indonesian invasion. This intervention nearly resulted in her being attacked by the Indonesian Air Force using Soviet-supplied Tupolev Tu-16KS-1 Badger naval bombers carrying anti-ship missiles. The attack was called off by a last-minute cease fire.[35]

Between 1964 and 1967, the Royal Navy deployed the Far East Fleet carriers Ark Royal, Centaur, and HMS Victorious in support of operations in Borneo during the Konfrontasi conflict between Indonesia and Malaysia. HMS Albion and Bulwark were deployed as commando carriers, and the Australian carrier HMAS Sydney served as a troop transport.[36]

Indo-Pakistan War of 1971

[edit]During the war, India deployed INS Vikrant against Pakistan from its station in the Andaman Islands for operations against Pakistani forces in the East (present day Bangladesh). Hawker Sea Hawks from the carrier successfully choked the Chittagong harbour and put it out of service.

U.S. carrier operations in Southeast Asia

[edit]The United States Navy fought "the most protracted, bitter, and costly war"[37] in the history of naval aviation from August 2, 1964, to August 15, 1973, in the waters of the South China Sea. Operating from two deployment points (Yankee Station and Dixie Station), carrier aircraft supported combat operations in South Vietnam and conducted bombing operations in conjunction with the U.S. Air Force in North Vietnam under Operations Flaming Dart, Rolling Thunder, and Linebacker. The number of carriers on the line varied during differing points of the conflict, but as many as six operated at one time during Operation Linebacker.

Twenty-one aircraft carriers, all of the attack carriers operational during the era except John F. Kennedy, deployed to Task Force 77 of the US Seventh Fleet, conducting 86 war cruises and operating 9,178 total days on the line in the Gulf of Tonkin. 530 aircraft were lost in combat and 329 more in operational accidents, causing the deaths of 377 naval aviators, with 64 others reported missing and 179 captured. 205 officers and men of the ship's complements of three carriers Forrestal, Enterprise, and Oriskany, were killed in major shipboard fires. At times some of the carrier groups operated over 12,000 miles from their home ports.

Falklands War

[edit]

During the Falklands War the United Kingdom was able to win a conflict 8,000 miles (13,000 km) from home in large part due to the use of the light fleet carrier HMS Hermes (1959) and the smaller "through deck cruiser" carrier HMS Invincible. The Falklands showed the value of STOVL aircraft, the Hawker Siddeley Harrier, both the RN Sea Harrier and press-ganged RAF Harrier variants, in defending the fleet and assault force from shore-based aircraft and in attacking the enemy. Sea Harriers shot down 21 fast-attack jets and suffered no aerial combat losses, although six were lost to accidents and ground fire. Helicopters from the carriers were used to deploy troops and for medevac, search and rescue and anti-submarine warfare.

Another lesson from the Falklands War resulted in the withdrawal of Argentina's aircraft carrier ARA Veinticinco de Mayo with her A-4Qs. The sinking of the Argentine cruiser ARA General Belgrano by the fast attack submarine HMS Conqueror showed that capital ships were vulnerable in nuclear submarines' hunting grounds.

Operations in the Persian Gulf

[edit]The U.S. has also made use of carriers in the Persian Gulf and Afghanistan and to protect its interests in the Pacific. During the 2003 invasion of Iraq U.S. aircraft carriers served as the primary base of American air power. Even without the ability to place significant numbers of aircraft in Middle Eastern airbases, the United States was capable of carrying out significant air attacks from carrier-based squadrons. Recently, U.S. aircraft carriers such as the Ronald Reagan provided air support for counter-insurgency operations in Iraq.

Key technologies

[edit]| Feature | First seen | First demonstrated on/at | First commissioned carrier | Entry into service | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight takeoff deck | 1910 | USS Birmingham (CL-2) | HMS Repulse (1916) | 1917 | |

| Full length flight deck | 1918 | HMS Argus (I49) | HMS Argus (I49) | 1918 | |

| Angled flight deck | 1948 | HMS Warrior (R31) | USS Antietam (CV-36) | 1952 | |

| Aircraft elevators | 1918 | HMS Argus (I49) | HMS Argus (I49) | 1918 | |

| Purpose-built carrier | 1918 | HMS Hermes (95) | IJN Hōshō | 1922 | |

| Arresting gear | 1911 | USS Pennsylvania (ACR-4) | HMS Argus (I49) | 1918 | Argus was fitted with longitudinal gear, by W.A.D. Forbes |

| Transverse arrestor gear | 1922 | USS Langley (CV-1) | Béarn | 1927 | |

| Hydraulic Arrestor Gear | 1927 | Béarn | Béarn | 1927 | |

| Starboard Island | 1924 | HMS Hermes (95) | HMS Hermes (95) | 1924 | |

| Hurricane Bow | 1924 | HMS Hermes (95) | HMS Hermes (95) | 1924 | |

| Aircraft catapult | 1915 | USS North Carolina (ACR-12) | USS Langley (CV 1) - compressed air USS Lexington (CV-2) - fly wheel HMS Courageous (50) - hydraulic |

1922 1927 1934 |

LCDR Henry Mustin made the first successful launch on 5 November 1915, |

| Steam Catapult | 1950 | HMS Perseus (R51) | HMS Ark Royal (R09) USS Hancock (CV-19) USS Shangri-La (CVA-38) |

1955 | Added to Hancock and Shangri-La during their SCB-27C/125 refits. |

| Jet Aviation | 1945 | HMS Ocean (R68) | USS Saipan (CVL-48) | 1948 | A Sea Vampire flown by Eric "Winkle" Brown made the first ever carrier landing on 4 December 1945 |

| Optical landing system | 1953 | HMS Illustrious (87) | HMS Ark Royal (R09) | 1955 | Invented in 1951 by Nicholas Goodhart |

| Nuclear marine propulsion | 1961 | USS Enterprise (CVN-65) | USS Enterprise CVN-65 | 1961 | |

| Ski-jump | 1973 | RAE Bedford | HMS Invincible (R05) | 1977 | |

| EMALS | 2010 | Lakehurst Maxfield Field | USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) | 2017 |

See also

[edit]- Modern United States Navy carrier air operations

- Project Habakkuk

- Seadrome

- Mobile offshore base (concept)

- Airborne aircraft carrier

- Floating airport (concept)

Types of ships that carry aircraft

[edit]- ASW carrier

- Escort carrier

- Helicopter carrier

- Light aircraft carrier

- Supercarrier

- Amphibious assault ship

- Seaplane tender

- Balloon carrier

- Submarine aircraft carrier

Related lists

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Note: three generations of Royal Navy aircraft carriers named HMS Hermes are mentioned in this article: HMS Hermes (1898), HMS Hermes (1924), and HMS Hermes (1959),

- ^ Military Ballooning During the Early Civil War, p 96, F. Stansbury Haydon, JHU Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8018-6442-9

- ^ Chambers's Supplementary Reader, p 12, W. and R. Chambers, BiblioBazaar, 2008, ISBN 0-554-87195-5

- ^ van Beverhoudt, Jr., Arnold E. (2003-01-01). "Carriers: Airpower at Sea - The Early Years / Part 1". sandcastlevi.com. Sandcastle VI. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ^ Military Aircraft, Origins to 1918, p 10, Justin D. Murphy, ABC-CLIO, 2005, ISBN 1-85109-488-1

- ^ Description and photograph of Foudre

- ^ "First US seaplane carrier, the USS Mississippi". Hazegray.org. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ Wakamiya is "credited with conducting the first successful carrier air raid in history"Source:GlobalSecurity.org

- ^ "Sabre et pinceau", Christian Polak, p. 92.

- ^ IJN Wakamiya Aircraft Carrier

- ^ Barry Watts and Williamson Murray, "Military Innovation in Peacetime," in Murray, Williamson; Millet, Allan R, eds. (1996). Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 385. ISBN 0-521-63760-0.

- ^ Halpern, Paul G. (11 October 2012). A Naval History of World War I. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-172-6.

- ^ Green, William (1962). War Planes of the Second World War: Volume Six: Floatplanes. London: Macdonald. pp. 90–91.

- ^ Clement Ader on the structure of the aircraft carrier:

"An airplane-carrying vessel is indispensable. These vessels will be constructed on a plan very different from what is currently used. First of all the deck will be cleared of all obstacles. It will be flat, as wide as possible without jeopardizing the nautical lines of the hull, and it will look like a landing field." Military Aviation, p35

On stowage:

"Of necessity, the airplanes will be stowed below decks; they would be solidly fixed anchored to their bases, each in its place, so they would not be affected with the pitching and rolling. Access to this lower decks would be by an elevator sufficiently long and wide to hold an airplane with its wings folded. A large, sliding trap would cover the hole in the deck, and it would have waterproof joints, so that neither rain nor seawater, from heavy seas could penetrate below." Military Aviation, p36

On the technique of landing:

"The ship will be headed straight into the wind, the stern clear, but a padded bulwark set up forward in case the airplane should run past the stop line" Military Aviation, p37. - ^ van Beverhoudt, Arnold E. Jr. (2003-01-01). "Carriers: Airpower at Sea - The Early Years / Part 2". sandcastlevi.com. Sandcastle VI. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ Barnes C.H. & James D.N (1989). Shorts Aircraft since 1900. London: Putnam. p. 60. ISBN 0-85177-819-4.

- ^ Friedman, p. 28

- ^ Sturtivant (1990), p.215

- ^ 269 Squadron History: 1914–1923

- ^ a b "HMS Furious 1917". Royal Navy. RN official web site. Archived from the original on 13 June 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ Probert, p. 46

- ^ a b "Hōshō was a carrier from the keel, the first of its kind completed in any navy of the world" Scot MacDonald US Navy History: Evolution of Aircraft Carriers Archived 2009-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Imperial Japanese Navy was a pioneer in naval aviation, having commissioned the world's first built-from-the-keel-up carrier, the Hosho." GlobalSecurity: Carrier Hosho.

- ^ CVL—Small Aircraft Carriers, Naval Historical Center, http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/shusn-no/cvl-no.htm. Retrieved 22 September 2006.

- ^ Black, Jeremy (2003). World War Two: A Military History. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 0-415-30534-9.

- ^ Francillon p.

- ^ a b c "The angled flight deck". Sea Power Centre Australia. Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ a b Friedman 1983, p.264

- ^ "U.S. Navy - A Brief History of Aircraft Carriers - USS Midway (CVB 41)". Chinfo.navy.mil. Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ "Peoples Planes Places" (PDF). Naval Historical Center. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ "oai.dtic.mil/oai/oai?verb=getRecord&metadataPrefix=html&identifier=ADA378145". Archived from the original on January 25, 2009.

- ^ "World Aircraft Carriers List: France". Hazegray.org. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ "Suez Crisis, 1956". Acig.org. Archived from the original on February 20, 2004. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ Tu-16 Badger: The stealth from the Southern Hemisphere - Rubrik HISTORY[usurped]

- ^ "British & Commonwealth units serving in Borneo, Brunei and supporting operations 1962 - 1966". Britains-smallwars.com. Archived from the original on 2009-01-25. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ^ René Francillon

Bibliography

[edit]- Francillon, René J, Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club US Carrier Operations off Vietnam, (1988) ISBN 0-87021-696-1

- Friedman, Norman (1988). British Carrier Aviation: The Evolution of the Ships and Their Aircraft. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-054-8.

- Nordeen, Lon, Air Warfare in the Missile Age, (1985) ISBN 1-58834-083-X

- Ader, Clement, "Military Aviation", 1909, Edited and translated by Lee Kennett, Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base Alabama, 2003, ISBN 1-58566-118-X

- Sheldon-Duplaix, Alexandre, Histoire mondiale des porte-avions: des origines à nos jours. (Boulogne-Billancourt: ETAI, DL, 2006).

- Friedman, Norman, U. S. Aircraft Carriers: an Illustrated Design History, Naval Institute Press, 1983 - ISBN 0-87021-739-9. Contains many detailed ship plans.

- Polak, Christian (2005). Sabre et Pinceau: Par d'autres Français au Japon. 1872-1960 (in French and Japanese). Hiroshi Ueki (植木 浩), Philippe Pons, foreword; 筆と刀・日本の中のもうひとつのフランス (1872-1960). éd. L'Harmattan.

- Williams, Alison J. "Aircraft carriers and the capacity to mobilise US power across the Pacific, 1919–1929," Journal of Historical Geography (2017) 15#1 71-81 Online free doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2017.07.008