Hadrumetum

| |

| Location | Tunisia |

|---|---|

| Region | Sousse Governorate |

| Coordinates | 35°49′28″N 10°38′20″E / 35.824444°N 10.638889°E |

Hadrumetum,[1] also known by many variant spellings and names, was a Phoenician colony that pre-dated Carthage. It subsequently became one of the most important cities in Roman Africa before Vandal and Umayyad conquerors left it ruined. In the early modern period, it was the village of Hammeim, now part of Sousse, Tunisia.

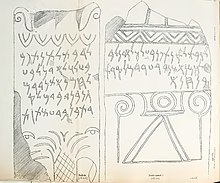

A number of punic steles were found during excavations at the site of the modern day Église Notre-Dame-de-l'Immaculée-Conception de Sousse [fr].

Names

[edit]The Phoenician and Punic name for the place was DRMT (𐤃𐤓𐤌𐤕), "Southern", or ʾDRMT (𐤀𐤃𐤓𐤌𐤕), "The Southern".[2] A similar structure appears in the Phoenician name for old Cadiz, which appears as Gadir ("Stronghold") or Agadir ("The Stronghold").

The ancient transcriptions of the name show a great deal of variation. Different Greeks hellenized the name as Adrýmē (Ἀδρύμη),[3] Adrýmēs (Ἀδρύμης), Adrýmēton (Ἀδρύμητον),[2] Adrýmētos (Ἀδρύμητος), Adramýtēs (Ἀδραμύτης), Adrámētós (Ἀδράμητος)[1] and Adrumetum (Ἀδρούμητον).[4] Surviving Roman inscriptions and coinage standardized its latinization as Hadrumetum[1] but it appears in other sources as Adrumetum,[3] Adrumetus,[5] Adrimetum, Hadrymetum, etc.[1] Upon its notional refounding as a Roman colony, its formal name was emended to Colonia Concordia Ulpia Trajana Augusta Frugifera Hadrumetina to honor its imperial sponsor.[1]

It was renamed Honoriopolis after the emperor Honorius in the early 5th century,[citation needed] then Hunericopolis after the Vandal king Huneric[6] and Justinianopolis[3] after the first few years of occupation from emperor Justinian I.[7]

Geography

[edit]Hadrumetum controlled the mouth of a small river[8] on the Gulf of Hammamet (Latin: Sinus Neapolitanus), an inlet of the Mediterranean along the Tunisian coast.[1]

History

[edit]Phoenician colony

[edit]In the 9th century BC,[citation needed] Tyrians established Hadrumetum[1] as a trading post and waypoint along their trade routes to Italy and the Strait of Gibraltar. Its establishment preceded Carthage's[9] but, like other western Phoenician colonies, it became part of the Carthaginian Empire[1] following Nebuchadnezzar II's long siege of Tyre in the 580s and 570s BC.

Carthaginian city

[edit]

Agathocles of Syracuse captured the town in 310 BC[1] during the Seventh Sicilian War, as part of his failed attempt to move the conflict to Africa. Hadrumetum later provided refuge to Hannibal and other Carthaginian survivors after their 202 BC defeat at Zama,[1] which decided the outcome of the Second Punic War. The total length of the Punic fortifications was apparently 6,410 meters (21,030 ft); some ruins survive.[10]

Roman city

[edit]During the Third Punic War, the government of Hadrumetum supported the Romans against Carthage[11] and, after Carthage's destruction in 146 BC, it received additional territory and the status of a free city in thanks.[12] During this period, it chose its own shufets (Latin: duumvir) and minted its own bronze coins with the head of "Neptune" or the Sun.[10]

During the civil war between Pompey and Julius Caesar, G. Considius Longus secured Hadrumetum for the Optimates with forces equivalent to two legions. Despite being reinforced by Gn. Calpurnius Piso's Berber cavalry and footmen from Clupea, however, he was obliged to allow Caesar to land nearby on 28 December 47 BC.[13] According to Suetonius, this landing was the occasion of the famously deft recovery, when Caesar tripped while coming ashore but dealt with the poor omen by grabbing handfuls of dirt and proclaiming "I have you now, Africa!" (Latin: teneo te Africa)[14] Caesar's attempts to negotiate with Longus were rejected but the campaign subsequently led to his victory over Metellus Scipio and Juba at Thapsus, after which Longus was killed by his own men for the money he was carrying[15] and the town went over to Caesar.[16]

Hadrumetum was one of the most important communities in Roman North Africa because of the fertility of its hinterland (modern Tunisia's Sahel), which made it an important source of Rome's grain supply. It quarreled with its neighbor Thysdrus over the temple of a goddess equated to Minerva, which stood on their shared border.[1]

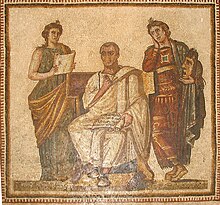

Under Augustus, Hadrumetum's coins bore his face obverse and the name (and often face) of Africa's proconsul reverse; after Augustus, the mint was closed.[10] Hadrumetum revolted while Vespasian was proconsul of Africa.[17] It nonetheless continued to prosper; Trajan gave it the rank of a Roman colony, giving its residents Roman citizenship.[3] A breathtaking legacy of intricate mosaics survives from this era, together with many early Christian objects from the catacombs. It was the second city in Roman Africa after Carthage and the birthplace of Clodius Albinus, who attempted to become emperor in the 190s.[10] At the end of the 3rd century, it became the capital of the new province of Byzacena[5] (modern Sahel, Tunisia).

Later history

[edit]In 434, it was largely destroyed by the Vandals;[5][10] their fervent Arianism produced a number of orthodox martyrs in the remaining community, including SS Felix and Victorian. A century later, Hadrumetum was retaken and rebuilt by the Byzantines during the Vandal War.[18] It was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate in the 7th century.

The ruins of Hadrumetum stood in the village of Hammeim,[3] 10 kilometers (6 mi) from the later Sousse,[8] which grew up to include them in its outskirts.

Under colonial rule, the French engineer A. Daux[which?] rediscovered the jetties and moles of the Roman town's commercial harbor and the line of its military harbor; both had been mostly artificial and have silted up since antiquity.[10] Louis Carton and Abbé Leynaud[which?] rediscovered the Christian catacombs in 1904; the tunnels extend for miles through small subterranean galleries filled with Roman and Byzantine sarcophagi and inscriptions.[10]

Ruins

[edit]In addition to the Punic walls, Roman harbors, and Byzantine catacombs, there are ruins of the Byzantine acropolis and basilica; the Roman horse track, cisterns, the theater; and a Punic necropolis.[10]

Religion

[edit]As a major Roman city, Hadrumetum produced a number of Christian saints, including Mavilus during the regional persecutions of Caracalla's reign and the Bishop Felix and proconsul Victorian during the Vandals' efforts to forcibly convert their subjects to Arianism. From 255 to 551, the city was the seat of a Christian bishopric. The see was revived in the 17th century as a Catholic titular see.

List of bishops

[edit]There were nine ancient bishops of Hadrumetum who are still known.[5]

- Polycarp, who appeared at the 256 Council of Carthage[19]

- St Felix, martyred by Gaiseric

- St Primasius

- Raphael de Figueredo (1681.05.14 – 1695.10.12)

- Salvator-Alexandre-Félix-Carmel Brincat (1889.05.12 – 1909.04.02)

- Giacinto Gaggia (1909.04.29 – 1913.10.28)

- Jean-Marie Bourchany (1914.01.13 – 1931.11.27)

- Carlo Re, IMC (1931.12.14 – 1951.12.29)

- Jorge Manrique Hurtado (1952.02.23 – 1956.07.28)

- Celestin Bezmalinovic, OP (1956.08.07 – 1967)

- Mijo Škvorc, SJ (1970.06.16 – 1989.02.15)

- Marian Błażej Kruszyłowicz, OFM Conv (1989.12.09 – present)

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Enc. Brit. (1911), p. 802.

- ^ a b Maldonado López (2013), pp. 43–45.

- ^ a b c d e New Class. Dict. (1860), s.v. "Hadrūmētum".

- ^ Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Hadrumētum

- ^ a b c d Cath. Enc. (1910).

- ^ O. Maenchen-Helfen, The World of the Huns. IX. footnote 113.

- ^ Merrills, Andy (October 2023). War, Rebellion and Epic in Byzantine North Africa. University of Leicester: Cambridge University press. p. 42. ISBN 9781009392013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Norie (1831), p. 348.

- ^ Sallust, Jug., 19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Enc. Brit. (1911), p. 803.

- ^ Appian, The Punic Wars, §94.

- ^ CIL, Vol. I, p. 84.

- ^ Caesar & al., Afr. War, Ch. iii.

- ^ Suetonius, Div. Jul., §59. (in Latin) & (in English)

- ^ Caesar & al., Afr. War, §76.

- ^ Caesar & al., Afr. War, §89.

- ^ Suetonius, Vesp., Ch. iv.

- ^ Procop., Build., Book VI, §6.

- ^ Cyprian. "Epistle LIII". andrews.edu. Retrieved Feb 16, 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- A New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, Mythology, and Geography, New York: Harper & Bros, 1860.

- Babelon, Ernest Charles François (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 802–803.

- Maldonado López, Gabriel (2013), Las Ciudades Fenicio Púnicas en el Norte de África... (PDF). (in Spanish)

- Norie, J.W. (1831), New Piloting Directions for the Mediterranean Sea..., London: J.W. Norie & Co.

- Pétridès, Sophrone (1910), "Hadrumetum", Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. VII, New York: Robert Appleton Co.

External links

[edit]- Sousse (Sūsa) Archived 2008-12-11 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopaedia of the Orient

- Adventures of Tunisia: A virtual tour of the historic sites of Sousse Archived 2008-09-22 at the Wayback Machine

- GigaCatholic, with titular incumbents lists and linked biographies