Humboldt squid

| Humboldt squid Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| A Humboldt squid swimming around ROV Tiburon, possibly attracted to its lights | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Oegopsida |

| Family: | Ommastrephidae |

| Subfamily: | Ommastrephinae |

| Genus: | Dosidicus Steenstrup, 1857 |

| Species: | D. gigas

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dosidicus gigas | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

The Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas), also known as jumbo squid or jumbo flying squid (EN), and Pota in Peru or Jibia in Chile (ES), is a large, predatory squid living in the eastern Pacific Ocean. It is the only known species of the genus Dosidicus of the subfamily Ommastrephinae, family Ommastrephidae.[4]

Humboldt squid typically reach a mantle length of 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in), making the species the largest member of its family. They are the most important squid worldwide for commercial fisheries, with the catch predominantly landed in Chile, Peru and Mexico; however, a 2015 warming waters fishery collapse in the Gulf of California remains unrecovered.[5][6] Like other members of the subfamily Ommastrephinae, they possess chromatophores which enable them to quickly change body coloration, known as 'metachrosis’ which is the rapid flash of their skin from red to white. They have a relatively short lifespan of just 1–2 years. They have a reputation for aggression toward humans, although this behavior may only occur during feeding times.

They are most commonly found at depths of 200 to 700 m (660 to 2,300 ft), from Tierra del Fuego to California. This species is spreading north into the waters of the Pacific Northwest, in Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, and Alaska.

Taxonomy

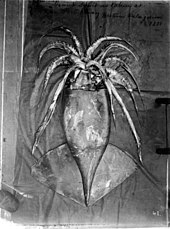

[edit]The existence of this creature was first reported to the scientific world by the Chilean priest and polymath Juan Ignacio Molina in 1782, who named it Sepia tunicata, Sepia being the cuttlefish genus. The French naturalist Alcide d'Orbigny renamed it Loligo gigas in 1835. In Chile, Claude Gay, another French naturalist, obtained some specimens and sent them to the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in Paris, where it was determined that the species did not belong with Loligo either. In 1857 the Danish zoologist Japetus Steenstrup proposed the new genus Dosidicus to house the species.[7]

The German zoologist George Pfeffer synonymized D. eschrichtii with D. gigas in 1912.[7][8]

The fossil species Dosidicus lomita is represented in statoliths from the Pliocene Lomita Marl of California, marking the earliest known occurrence of the genus.[9]

Common names

[edit]This species is most often known as jumbo squid in English, but has also been called jumbo flying squid or Humboldt squid, with the last name most popular in naturalist sources.[10] The name Humboldt refers to the Humboldt Current, off the southwestern coast of South America, where it was first collected.[11]

A general name for this species in Spanish in Latin America is calamar gigante.[12][13] Local names for it are jibia in Chile[14] or pota in Peru.[15] They notably rapidly flash red and white when captured, earning them the nickname diablo rojo (meaning 'red devil') among local fishermen in Baja California, Mexico.[16]

Description

[edit]The Humboldt squid is the largest of the Ommastrephid squids, as some individuals may grow to 1.5 m (5 ft) in mantle length[17][18] and weigh up to 50 kg (110 lb).[8] They appear to be sexually dimorphic: on average the females mature at larger sizes than the males.[19] Generally, the mantle (or body) constitutes about 56–62% of the animal's mass (which includes the fins or wings), the arms and tentacles about 11–15%, the head (including eyes and beak) about 10–13%, the outer skin (cuticle) 2.5–5.0%, the liver 4.2–5.6%, with the rest made up of the other inner organs. The gonads consist of 1.5–15.0% of the total mass. The gladius (the single inner 'bone') is 0.7–1.0%. Precise ratios depend on the age, sex and sizes of the individual squid.[20]

They are propelled by water ejected through a hyponome (siphon) and by two triangular fins.[21] The Humboldt's two tentacles are elastic and can lash out with remarkable speed to grab hold of prey, holding it fast with the help of a wealth of suckers on each tentacle; these then retract and the prey is drawn toward a large, razor-sharp beak.[21]

Behavior

[edit]

Humboldt squid are carnivorous marine invertebrates that move in shoals of up to 1,200 individuals. They swim at speeds up to 24 km/h (15 mph; 13 kn).[22]

Electronic tagging has shown Humboldt squid undergo diel vertical migrations, which bring them closer to the surface from dusk to dawn.[23] Humboldt squid are thought to have a lifespan of about a year, although larger individuals may survive up to 2 years.[8]

Crittercams attached to two or three Humboldt squid revealed the species has two modes of color-generating (chromogenic) behavior:

- The entire body flashes between the colors red and white at 2–4 Hz when in the presence of other squid, this behavior likely representing intraspecific signaling. This flashing can be modulated in frequency, amplitude and in phase synchronization with each other. What they are communicating to each other is unknown – it could be an invitation for sex or a warning to not get too close.

- The other chromogenic mode is a much slower "flickering" of red and white waves which travel up and down the body, this is thought to be a dynamic type of camouflage which mimics the undulating pattern of sunlight filtering through the water, like sunlight on the bottom of a swimming pool. The squid appear to be able to control this to some degree, pausing or stopping it.

Although these two chromogenic modes are not known in other squid species, other species do have functionally similar behaviors.[24][25]

Distribution

[edit]

The Humboldt squid lives at depths of 200 to 700 m (660 to 2,300 ft) in the eastern Pacific (Notably in Chile and Peru), ranging from Tierra del Fuego north to California. Recently, the squid have been appearing farther north, as far as British Columbia.[11] They have also ventured into Puget Sound.[26]

Though they usually prefer deep water, between 1,000 and 1,500 squid washed up on the Long Beach Peninsula in southwest Washington in late 2004[27] and red algae were a speculated cause for the late 2012 beaching of an unspecified number of juvenile squid (average length 50 cm [1.5 ft]) at Monterey Bay over a 2-month period.[28]

Changes in distribution

[edit]Humboldt squid are generally found in the warm Pacific waters off the Mexican coast; studies published in the early 2000s indicated an increase in northern migration. The large 1997–1998 El Niño event triggered the first sightings of Humboldt squid in Monterey Bay. Then, during the minor El Niño event of 2002, they returned to Monterey Bay in higher numbers and have been seen there year-round since then. Similar trends have been shown off the coasts of Washington, Oregon, and even Alaska, although no year-round Humboldt squid populations are in these locations. This change in migration is suggested to be due to warming waters during El Niño events, but other factors, such as a decrease in upper trophic level predators that would compete with the squid for food, could be impacting the migration shift, as well.[11][29]

A 2017 Chinese study found that D. gigas is affected by El Niño events in the waters off Peru. The squid populations cluster into groups less, and are thus more dispersed, during El Niño events. Additionally, during warm El Niño conditions and high water temperature the waters off Peru were less favourable for D. gigas.[30]

Ecology

[edit]Prey and feeding behavior

[edit]The Humboldt squid's diet consists mainly of small fish (lanternfish, in particular), crustaceans, cephalopods, and copepods.[31] The squid uses its barbed tentacle suckers to grab its prey and slices and tears the victim's flesh with its beak and radula. They often approach prey quickly with all 10 appendages extended forward in a cone-like shape. Upon reaching striking distance, they open their eight swimming and grasping arms, and extend two long tentacles covered in sharp hooks, grabbing their prey and pulling it back toward a parrot-like beak, which can easily cause serious lacerations to human flesh. These two longer tentacles can reach full length, grab prey, and retract so fast that almost the entire event happens in one frame of a normal-speed video camera. Each of the squid's suckers is ringed with sharp teeth, and the beak can tear flesh, although they are believed to lack the jaw strength to crack heavy bone.[21]

Their behavior while feeding often includes cannibalism and they have been seen to readily attack injured or vulnerable squid in their shoal. A quarter of squid stomachs analyzed contained remains of other squid.[32] This behavior may account for a large proportion of their rapid growth.[21][33] An investigation of the stomach contents of over 2,000 squid caught outside of the Exclusive Economic Zone off the coasts of Chile found that cannibalism was likely the most important source of food. Over half had the beaks of D. gigas in their stomachs, and D. gigas was the most common prey item. The researchers do note, however, that squid jigged in the light field around the survey vessel showed much more cannibalism.[19]

Until recently, claims of cooperative or coordinated hunting in D. gigas were considered unconfirmed and without scientific merit.[34] However, research conducted between 2007 and 2011 indicates this species does engage in cooperative hunting.[35]

The squid are known for their speed at eating; they feast on hooked fish, stripping them to the bone before fishermen can reel them in.[21]

Reproduction

[edit]Females lay gelatinous egg masses that are almost entirely transparent and float freely in the water column. The size of the egg mass correlates with the size of the female that laid it; large females can lay egg masses up to 3–4 m in diameter,[36] while smaller females lay egg masses about one meter in diameter. Records of egg masses are extremely sparse because they are rarely encountered by humans, but from the few masses found to date, the egg masses seem to contain anywhere from 5,000 to 4.1 million eggs, depending on size.[37]

Relationship to humans

[edit]Fisheries

[edit] |

|

Commercially, this species has been caught to serve the European market (mainly Spain, Italy, France, and Ireland), Russia, China, Japan, Southeast Asia, and increasingly North and South American markets.[citation needed]

It is the most popular squid in the world, as of 2019 a third of all squid hunted is this species.[39]

The method used by both artisanal fishermen as well as more industrial operations to catch the squid is known as jigging.[13][19] Squid jigging is a relatively novel method of fishing in the Americas.[40] It is done by handlining by artisanal fishermen, or by using mechanical jiggers.[13][41] Jigging involves constantly jerking the line up and down to simulate prey; a reel with an elliptical or oval-shaped hub helps with this.[41][42] Squid jigging is done at night, using bright overhead lights from the fishing boats which reflect brightly off the jigs and plankton in the seawater, luring the squid toward the surface to feed. The seem to prefer striking at the jigs from adjacent shadowed areas, especially the shade under the hull of the boat.[40][41] Often as many as 8 to 12 jigs are on snoods on one handline, and many more are used on automated squid jigging systems.[41] The lines are hung anywhere from 10 to 100m in depth, depending on the power of the lamps used.[41][42]

The jigs are called poteras in Spanish. Different types of jigs are suitable for either handlining or for mechanical jigging for jumbo squid. They are made from bakelite and/or stainless steel, and measure 75 to 480mm in length. Jigs can have a single axis, or one to three 'arms' (ejes) which wave around when the jig is jerked,[13] and a series of crowns (coronas) of bristle-like wire-hooks, the hooks lacking barbs, making up the tail.[13][41] The body of the jigs is usually phosphorescent,[13] but glow-in-the-dark lures may be attached to them.[42] Jigs are extremely selective, not only can one type of jig attract only squid, often the jigs can select for a single species of squid, and even specific sizes of that species. The more arms and crowns, the more hooks, the higher the chances of snagging and actually reeling in the squid.[13]

Since the 1990s, the most important areas for landings of Humboldt squid are Chile, Mexico, and Peru (122–297, 53–66, and 291–435 thousand tonnes, respectively, in the period 2005–2007).[19]

Based on 2009 national fisheries data, in Mexico this species represents 95% of the total recorded catch of squid. 88% of this is caught off the coasts of Sonora and Baja California Sur.[12]

As food

[edit]

Because the flesh of the animals is saturated with ammonium chloride (salmiak), which keeps them neutrally buoyant in seawater, the animal tastes unpleasantly salty, sour, and bitter when fresh. To make the squid more palatable for the frozen squid market, freshly caught Humboldt squid are commercially processed by first mechanically tenderizing them, dropping them in icy water with 1% mixture of lactic and citric acid for three hours, then washed, then soaked in another vat with a 6% brine solution for three hours. There is also a method for home cooks to neutralize the unpleasant taste.[14]

Compared to other types of seafood, Humboldt squid is inexpensive in Pacific South America, retailing around US$0.30/kg in Peru, and about US$2.00/kg in Chile, in the early 2010s.[14][15]

In Chile the squid is eaten in chupes and paila marina.[14] In Peru, the practice of making ceviche from cheap squid began in the poorer parts of Lima when the meat became available in the 1990s, and has since spread to Cuzco. It is sold on the street in food carts, as well as cevicherias, restaurants dedicated to this cuisine.[15] In the United States it is made into 'squid steaks'.

Aggression toward humans

[edit]Numerous accounts have the squid attacking fishermen and divers.[43] Their coloring and aggressive reputation have earned them the nickname diablos rojos (red devils) from fishermen off the coast of Mexico, as they flash red and white when struggling on a line.[16]

Although Humboldt squid have a reputation of being aggressive toward humans, some disagreement exists on this subject. Research suggests these squid are aggressive only while feeding; at other times, they are quite passive.[32] Some scientists claim the only reports of aggression toward humans have occurred when reflective diving gear or flashing lights have been present as a provocation. Roger Uzun, a veteran scuba diver and amateur underwater videographer who swam with a swarm of the animals for about 20 minutes, said they seemed to be more curious than aggressive.[44] In circumstances where these animals are not feeding or being hunted, they exhibit curious and intelligent behavior.[45]

Recent footage of shoals of these animals demonstrates a tendency to meet unfamiliar objects aggressively. Having risen to depths of 130–200 m (430–660 ft) below the surface to feed (up from their typical 700 m (2,300 ft) diving depth, beyond the range of human diving), they have attacked deep-sea cameras and rendered them inoperable. Humboldt squid have also been observed engaging in swarm behavior when met by the lights of submersibles, suggesting that they may follow or are attracted to light. Reports of recreational scuba divers being attacked by Humboldt squid have been confirmed.[46][47]

Model organism for early Marine Science in Latin America

[edit]In Chile, at the end of the 50s and early 60s, electrophysiological and neurophysiological studies were carried out by the Montemar Institute of Marine Biology,[48][49][50][51][52] in Valparaiso, Chile. The remarkable size of the squid giant axon and squid giant synapse possessed by the Humboldt squid made it ideal for manipulative work in the laboratory.[48] This research was chronicled in the documentary Montemar y Los Laberintos de la Memoria [Montemar and The Labyrinths of Memory]. 2016.

Conservation

[edit]A 2008 study predicted that ocean acidification will lower the Humboldt squid's metabolic rate by 31% and activity levels by 45% by the end of the 21st century. It also predicted that the squid wouldn't be able to spend as much of the day in deeper and colder waters, as a larger proportion of the ocean would fall into the oxygen minimum zone.[53]

A more recent study, however, provided empirical and theoretical evidence that the squid metabolism was unaffected by ocean acidification.[54]

In popular media

[edit]The Humboldt squid was featured in the final episode of the 2009 BBC's Last Chance to See with Stephen Fry and Mark Carwardine. The episode was about blue whales, but the presenters interviewed fishermen who talked about the exploding diablo rojo population in the Sea of Cortez and human attacks, and showed a squid trying to take a bite of a protectively clad forearm.

In 2016 the squid featured in various television shows. Man Eating Super Squid: A Monster Invasion on the National Geographic Wild channel explored various attacks by Humboldt squid in Mexico. In the show, the squid is referred to as a real-life kraken and as "a global threat".[55] The second show was River Monsters: Devil of the Deep, where show host Jeremy Wade talks to fishermen allegedly attacked by the squid in the Sea of Cortez, and then catches the animals off the coast of Peru.[56] In the British Fishing Impossible, mail-clad divers plan to capture a Humboldt squid by hand in the Pacific Ocean, but are prevented from doing so due to bad weather.[57] In BBC Earth's Blue Planet II the squid's cannibalistic pack hunting was captured on film for the first time.[58]

See also

[edit]- Cephalopod size

- Colossal squid

- Giant squid

- Thysanoteuthis rhombus

- Squid as food

- William Gilly§Humboldt squid

References

[edit]- ^ "Statoliths of Cenozoic teuthoid cephalopods from North America | The Palaeontological Association". www.palass.org. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- ^ Barratt, I.; Allcock, L. (2014). "Dosidicus gigas". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T162959A958088. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T162959A958088.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b Julian Finn (2016). "Dosidicus gigas (d'Orbigny [in 1834–1847], 1835)". World Register of Marine Species. Flanders Marine Institute. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "Humboldt squid in California". Gilly Lab. Fall 2007. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ Frawley, Timothy H; Briscoe, Dana K; Daniel, Patrick C; Britten, Gregory L; Crowder, Larry B; Robinson, Carlos J; Gilly, William F (18 July 2019). "Impacts of a shift to a warm-water regime in the Gulf of California on jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas)". ICES Journal of Marine Science: fsz133. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsz133.

- ^ "Jumbo squid mystery solved". EurekAlert!. July 18, 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ a b Ibáñez, Christian M.; Sepúlveda, Roger D.; Ulloa, Patricio; Keyl, Friedemann; M. Cecilia, Pardo-Gandarillas (1 July 2015). "The biology and ecology of the jumbo squid Dosidicus gigas (Cephalopoda) in Chilean waters: a review". Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research. 43 (3): 402–414. doi:10.3856/vol43-issue3-fulltext-2. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Nigmatullin, C.M.; Nesis, K.N.; Arkhipkin, A.I. (2001). "A review of the biology of the jumbo squid Dosidicus gigas (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae)". Fisheries Research. 54 (1): 9–19. Bibcode:2001FishR..54....9N. doi:10.1016/S0165-7836(01)00371-X.

- ^ "Statoliths of Cenozoic teuthoid cephalopods from North America | The Palaeontological Association". www.palass.org. Retrieved 2023-10-09.

- ^ see totality of references

- ^ a b c Zeidberg, L.; Robinson, B.H. (2007). "Invasive range expansion by the Humboldt squid, Dosidicus gigas, in the eastern North Pacific". PNAS. 104 (31): 12948–12950. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10412948Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702043104. PMC 1937572. PMID 17646649.

- ^ a b Anuario estadístico de pesca (2009) (Report) (in Spanish). SAGARPA, México. 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g Julio Alarcon; Carlos Martín Salazar; Juan Valles; Rodolfo Cornejo; German Chacón; Juan Chambilla. Características Técnicas de las Poteras Utilizadas para el Calamar Gigante 'Dosidicus gigas' en el Mar Peruano (Report) (in Spanish). Instituto del Mar de Perú (IMARPE). Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Stuart, Jim (22 April 2010). "Eating Jibia: Chilean Humbolt Squid". Eating Chilean. Jim Stuart. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Knowlton, David (16 February 2014). "Food Cart Squid Ceviche; Good, Tasty, and Cheap". Cuzco Eats. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ a b Floyd, Mark (June 13, 2008). "Scientists See Squid Attack Squid". LiveScience. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ Glaubrecht, M.; Salcedo-Vargas, M.A. (2004). "The Humboldt squid Dosidicus gigas (Orbigny, 1835) history of the Berlin specimen, with a reappraisal of other (bathy-)pelagic gigantic cephalopods (Mollusca, Ommastrephidae, Architeuthidae)". Zoosystematics and Evolution. 80 (1): 53–69. doi:10.1002/mmnz.20040800105.

- ^ Norman, M.D. 2000. Cephalopods: A World Guide. ConchBooks

- ^ a b c d Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Lu, H.; Chen, Y.; Qian, W. (2010). "Fishery biology of the jumbo flying squid Dosidicus gigas off the Exclusive Economic Zone of Chilean waters". Scientia Marina. 74 (4): 687–695. doi:10.3989/scimar.2010.74n4687.

- ^ Ивановна, Перова Людмила; Леонидович, Винокур Михаил; Павлович, Андреев Михаил (17 July 2012). "Технологическая характеристика гигантского кальмара дозидикуса (Dosidicus gigas) и его рациональное использование" [Technological characteristic of giant squid dosidicus (Dosidicus gigas) and its rational use]. Вестник Астраханского государственного технического университета, series Рыбное хозяйство (in Russian). 2012 (2). ISSN 2073-5529. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Tennesen, Michael (December 1, 2004). "The Curious Case of the Cannibal Squid". National Wildlife Magazine, Dec/Jan 2005, vol. 43 no. 1. National Wildlife Federation. Archived from the original on February 9, 2007. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ "Jumbo/Humboldt Squid ~ MarineBio Conservation Society". Retrieved 2023-11-18.

- ^ Gilly, W.F.; Markaida, U.; Baxter, C.H.; Block, B.A.; Boustany, A.; Zeidberg, L.; et al. (2006). "Vertical and horizontal migrations by the jumbo squid Dosidicus gigas revealed by electronic tagging" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 324: 1–17. Bibcode:2006MEPS..324....1G. doi:10.3354/meps324001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ^ Lee, Jane J. (21 January 2015). "Watch Jumbo squid speak by 'flashing' each other". National Geographic. National Geographic. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Rosen, Hannah; Gilly, William; Bell, Lauren; Abernathy, Kyler; Marshall, Greg (2015). "Chromogenic behaviour of the Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas) studied in situ with an animal-borne video package". Journal of Experimental Biology. 2015 (218): 265–275. doi:10.1242/jeb.114157. PMID 25609785. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Giant squid caught in West Seattle", KING-TV, August 15, 2009, archived from the original on September 13, 2012

- ^ Blumenthal, Les (April 27, 2008). "Aggressive eating machines spotted on our coast (2008)". The News Tribune. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ "Jumbo Flying Squid Pile Up On Calif. Beach". ABC News. December 11, 2012. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- ^ "Humboldt squid Found in Pebble Beach (2003)". Sanctuary Integrated Monitoring Network. Archived from the original on 2012-05-07. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ Feng, Yongjiu; Cui, Li; Chen, Xinjun; Liu, Yu (10 May 2017). "A comparative study of spatially clustered distribution of jumbo flying squid (Dosidicus gigas) offshore Peru". Journal of Ocean University of China. 16 (3): 490–500. Bibcode:2017JOUC...16..490F. doi:10.1007/s11802-017-3214-y. S2CID 90093670.

- ^ Dosidicus gigas. (n.d.). Animal Diversity Web. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Dosidicus_gigas/

- ^ a b Life. Extraordinary Animals, Extreme Behaviour by BBC Books, Martha Holmes & Michael Gunton, 2009, ISBN 978 1846076428, pg 22

- ^ Squid Sensitivity Discover Magazine April, 2003

- ^ Roger T Hanlon, John B Messinger, Cephalopod Behavior, p. 56, Cambridge University Press, 1996

- ^ Helena Smith (June 5, 2012). "Coordinated Hunting in Red Devils". Deep Sea News. Archived from the original on June 11, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- ^ Staaf, DJ; Camarillo-Coop, S; Haddock, SHD; Nyack, AC; Payne, J; Salinas-Zavala, CA; Seibel, BA; Trueblood, L; Widmer, C; Gilly, WF (2008). "Natural egg mass deposition by the Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas) in the Gulf of California and characteristics of hatchlings and paralarvae". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 88 (4): 759–770. Bibcode:2008JMBUK..88..759S. doi:10.1017/S0025315408001422. S2CID 15365497.

- ^ Birk, Matthew A.; Paight, C.; Seibel, Brad A. (2017). "Observations of multiple pelagic egg masses from small-sized jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas) in the Gulf of California". Journal of Natural History. 51 (43–44): 2569–2584. Bibcode:2017JNatH..51.2569B. doi:10.1080/00222933.2016.1209248. S2CID 88699091.

- ^ "Fisheries and Aquaculture - Global Production". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ^ Álvarez Armenta, Andrés; Carvajal Millán, Elizabeth; Pacheco Aguilar, Ramón; García Sánchez, Guillermina; Márquez Ríos, Enrique; Scheuren Acevedo, Susana María; Ramírez Suárez, Juan Carlos (March 2019). "Partial Characterization of a Low-Molecular-Mass Fraction with Cryoprotectant Activity from Jumbo Squid (Dosidicus gigas) Mantle Muscle". Food Technology & Biotechnology. 57 (1): 39–47. doi:10.17113/ftb.57.01.19.5848. PMC 6600302. PMID 31316275.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Daniel L.; Adelman, William J.; Arnold, John M. (1990). Squid as experimental animals. Springer. p. 21. ISBN 0-306-43513-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Bjarnason, B. A. (1992). Handlining and squid jigging. FAO training series, No. 23. Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 92-5-103100-2.

- ^ a b c Ream, Micki; Wachtel, Molly (12 May 2010). "Squid "jigging" brings elusive cephalopods up from Sea of Cortez". Scientific American - Expeditions. Springer Nature. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Pete (March 26, 2007). "Warning lights of the sea". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ Jumbo squid invade San Diego shores, spook divers, Associated Press, July 17, 2009

- ^ Zimmerman, Tim (December 2, 2010). "It's Hard Out Here for a Shrimp". Outside Online. Archived from the original on April 6, 2010. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ "Video: Giant squid attacks diver". 2.nbc13.com. July 17, 2009. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ "Humboldt or Jumbo Squid Fact Sheet". Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on November 2, 2011. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ a b SMACH, Sociedad Malacológica de Chile (2021). "Montemar y los Laberintos de la Memoria". Archived from the original on 2021-09-23. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ Luxoro, M (1960). "Incorporation of Amino-Acids labelled with Carbon-14 in Nerve Proteins during Activity and Recovery". Nature. 188 (4756): 1119–1120. Bibcode:1960Natur.188.1119L. doi:10.1038/1881119a0. PMID 13764493. S2CID 4148613.

- ^ Rojas, & Luxoro (1963). "Micro-injection of Trypsin into Axons of Squid". Nature. 199 (4888): 78–79. Bibcode:1963Natur.199...78R. doi:10.1038/199078b0. PMID 14047953. S2CID 4278673.

- ^ Tasaki, & Luxoro (1964). "Intracellular Perfusion of Chilean Giant Squid Axons". Science. 145 (3638): 1313–1315. Bibcode:1964Sci...145.1313T. doi:10.1126/science.145.3638.1313. PMID 14173418. S2CID 8006468.

- ^ Tasaki, Luxoro & Ruarte (1965). "Electrophysiological Studies of Chilean Squid Axons under Internal Perfusion with Sodium-Rich Media". Science. 150 (3698): 899–901. Bibcode:1965Sci...150..899T. doi:10.1126/science.150.3698.899. PMID 5835790. S2CID 45099323.

- ^ Rosa, Rui; Seibel, Brad A. (2008). "Synergistic effects of climate-related variables suggest future physiological impairment in a top oceanic predator". PNAS. 105 (52): 20776–0780. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10520776R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806886105. PMC 2634909. PMID 19075232.

- ^ Birk, Matthew A.; McLean, Erin L.; Seibel, Brad A. (2018). "Ocean acidification does not limit squid metabolism via blood oxygen supply". Journal of Experimental Biology. 221 (19): jeb187443. doi:10.1242/jeb.187443. PMID 30111559.

- ^ "Man Eating Super Squid: A Monster Invasion". Pink Ink. 2016-03-29. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "River Monsters: Monster Sized Special". Pink Ink. 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Fishing Impossible, Series 1 Episode 3". Archived from the original on 2016-10-12. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- ^ Knapton, Sarah (2017-11-03). "Blue Planet II: giant cannibalistic squid filmed hunting in packs for first time". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

External links

[edit]- "CephBase: Humboldt squid". Archived from the original on 2005-08-17.

- SQUID4KIDS free of charge squid for dissection, Gilly Lab

- Squidfish.net, forum on all things squid