Aestheticism

Aestheticism (also known as the aesthetic movement) was an art movement in the late 19th century that valued the appearance of literature, music, fonts and the arts over their functions.[1][2] According to Aestheticism, art should be produced to be beautiful, rather than to teach a lesson, create a parallel, or perform another didactic purpose, a sentiment best illustrated by the slogan "art for art's sake." Aestheticism flourished in the 1870s and 1880s, gaining prominence and the support of notable writers such as Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde.

Aestheticism challenged the values of mainstream Victorian culture, as many Victorians believed that literature and art fulfilled important ethical roles.[3] Writing in The Guardian, Fiona McCarthy states that "the aesthetic movement stood in stark and sometimes shocking contrast to the crass materialism of Britain in the 19th century."[4]

Aestheticism was named by the critic Walter Hamilton in The Aesthetic Movement in England in 1882.[5] By the 1890s, decadence, a term with origins in common with aestheticism, was in use across Europe.[3]

Origin

[edit]Aestheticism has its roots in German Romanticism. Though the term "aesthetic" derives from Greek, Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten's Aesthetica (1750) made important use of it in German before Immanuel Kant incorporated it into his philosophy in the Critique of Judgment (1790). Kant, in turn, influenced Friedrich Schiller's Aesthetic Letters (1794) and his concept of art as Spiel (Play): "Man is never so serious as when he plays; man is wholly man only when he plays". In the Letters, Schiller proclaimed salvation through art:

Man has lost his dignity, but Art has saved it, and preserved it for him in expressive marbles. Truth still lives in fiction, and from the copy the original will be restored.

These ideas were imported to the English-speaking world largely through the efforts of Thomas Carlyle, whose Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825), Critical and Miscellaneous Essays and Sartor Resartus (1833–1834) introduced and advocated aestheticism while also, if not marking the earliest use of the word "aesthetic" in the English language, certainly popularising it. Ruth apRoberts declared him the "apostle of aesthetics in England, 1825–1827", in recognition of his pioneering influence on the subsequent development of the aesthetic movement.[6]

Aesthetic literature

[edit]The British decadent writers were much influenced by the Oxford professor Walter Pater and his essays published during 1867–1868, in which he stated that one had to live life intensely, and seek beauty. His text Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) was very popular among art-oriented young men of the late 19th century. Writers of the Decadent movement used the slogan "Art for Art's Sake" (L'art pour l'art), the origin of which is debated. Some claim that it was created by the philosopher Victor Cousin, although Angela Leighton notes that it was used by Benjamin Constant as early as 1804 in the work On Form: Poetry, Aestheticism and the Legacy of a Word (2007).[7] It is generally accepted to have been popularised by Théophile Gautier in France, who used the phrase to suggest that art and morality were separate.

The artists and writers of Aesthetic style tended to profess that the Arts should provide refined sensuous pleasure, rather than convey moral or sentimental messages. As a consequence, they did not accept John Ruskin, Matthew Arnold, and George MacDonald's conception of art as something moral or useful, "Art for truth's sake".[8] Instead, they believed that Art did not have any didactic purpose; it only needed to be beautiful. The Aesthetes developed a cult of beauty, which they considered the basic factor of art. Life should copy Art, they asserted. They considered nature as crude and lacking in design when compared to art. The main characteristics of the style were: suggestion rather than statement, sensuality, great use of symbols, and synaesthetic/Ideasthetic effects—that is, correspondence between words, colours and music. Music was used to establish mood.[citation needed]

Predecessors of the Aesthetes included John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley, and some of the Pre-Raphaelites who themselves were a legacy of the Romantic spirit. There are a few significant continuities between the Pre-Raphaelite philosophy and that of the Aesthetes: Dedication to the idea of 'Art for Art's Sake'; admiration of, and constant striving for, beauty; escapism through visual and literary arts; craftsmanship that is both careful and self-conscious; mutual interest in merging the arts of various media. This final idea is promoted in the poem L'Art by Théophile Gautier, who compared the poet to the sculptor and painter.[9] Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones are most strongly associated with Aestheticism. However, their approach to Aestheticism did not share the creed of 'Art for Art's Sake' but rather "a spirited reassertion of those principles of colour, beauty, love, and cleanness that the drab, agitated, discouraging world of the mid-nineteenth century needed so much."[10] This reassertion of beauty in a drab world also connects to Pre-Raphaelite escapism in art and poetry.

In Britain the best representatives were Oscar Wilde, Algernon Charles Swinburne (both influenced by the French Symbolists), James McNeill Whistler and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. These writers and their style were satirised by Gilbert and Sullivan's comic opera Patience and other works, such as F. C. Burnand's drama The Colonel, and in comic magazines such as Punch, particularly in works by George Du Maurier.[11]

Compton Mackenzie's novel Sinister Street makes use of the type as a phase through which the protagonist passes as he is influenced by older, decadent individuals. The novels of Evelyn Waugh, who was a young participant of aesthete society at Oxford University, describe the aesthetes mostly satirically, but also as a former participant. Some names associated with this assemblage are Robert Byron, Evelyn Waugh, Harold Acton, Nancy Mitford, A.E. Housman and Anthony Powell.

Aesthetic fine art

[edit]

Artists associated with the Aesthetic style include Simeon Solomon, James McNeill Whistler, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Albert Joseph Moore, GF Watts and Aubrey Beardsley.[4] Although the work of Edward Burne-Jones was exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery which promoted the movement, it is narrative and conveys moral or sentimental messages hence falling outside the movement's purported programme.

Artists such as Rossetti focused more on simply painting beautiful women than aiming for a moral message, as is apparent in the famous “Lady Lilith” and “Mona Vanna.”[12][13] John Ruskin, a former friend of Rossetti's, said that Rossetti was “lost in the Inferno of London.”[14] Rossetti painted many more aestheticism paintings in his life, including “Venus Verticordia” and “Proserpine.”

Aesthetic decorative arts

[edit]

According to Christopher Dresser, the primary element of decorative art is utility. The maxim "art for art's sake," identifying art or beauty as the primary element in other branches of the Aesthetic Movement, especially fine art, cannot apply in this context. That is, decorative art must first have utility, but may also be beautiful.[15] However, according to Michael Shindler, the decorative art branch of the Aesthetic Movement, was less the utilitarian cousin of Aestheticism's main 'pure' branch, and more the very means by which aesthetes exercised their fundamental design strategy. Like contemporary art, Shindler writes that aestheticism was born of "the conundrum of constituting one’s life in relation to an exterior work" and that it "attempted to overcome" this problem "by subsuming artists within their work in the hope of yielding—more than mere objects—lives which could be living artworks." Thus, "beautiful things became the sensuous set pieces of a drama in which artists were not like their forebears a sort of crew of anonymous stagehands, but stars. Consequently, aesthetes made idols of portraits, prayers of poems, altars of writing desks, chapels of dining rooms, and fallen angels of their fellow men."[16]

Government Schools of Design were founded from 1837 onwards in order to improve the design of British goods. Following the Great Exhibition of 1851 efforts were intensified and oriental objects were purchased for the schools teaching collections. Owen Jones, architect and orientalist, was requested to set out key principles of design and these became not only the basis of the schools teaching but also the propositions that preface The Grammar of Ornament (1856), which is still regarded as the finest systematic study or practical sourcebook of historic world ornament.

Jones identified the need for a new and modern style that would meet the requirements of the modern world, rather than the continual re-cycling of historic styles, but saw no reason to reject the lessons of the past. Christopher Dresser, a student and later Professor at the school worked with Owen Jones on The Grammar of Ornament, as well as on the 1863 decoration of the oriental courts (Chinese, Japanese, and Indian) at the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), advanced the search for a new style with his two publications The Art of Decorative Design 1862, and Principles of Design 1873.

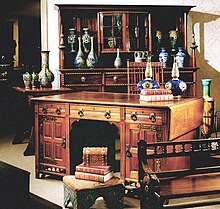

Production of Aesthetic style furniture was limited to approximately the late 19th century.[citation needed] Aesthetic style furniture is characterized by several common themes:

- Ebonized wood with gilt highlights.

- Far Eastern influence.

- Prominent use of nature, especially flowers, birds, ginkgo leaves, and peacock feathers.

- Blue and white on porcelain and other fine china.

Ebonized furniture means that the wood is painted or stained to a black ebony finish. The furniture is sometimes completely ebony-colored. More often however, there is gilding added to the carved surfaces of the feathers or stylized flowers that adorn the furniture.[citation needed]

As aesthetic movement decor was similar to the corresponding writing style in that it was about sensuality and nature, nature themes often appear on the furniture. A typical aesthetic feature is the gilded carved flower, or the stylized peacock feather. Colored paintings of birds or flowers are often seen. Non-ebonized aesthetic movement furniture may have realistic-looking three-dimensional-like renditions of birds or flowers carved into the wood.

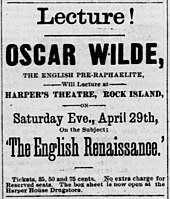

Contrasting with the ebonized-gilt furniture is use of blue and white for porcelain and china. Similar themes of peacock feathers and nature would be used in blue and white tones on dinnerware and other crockery. The blue and white design was also popular on square porcelain tiles. It is reported that Oscar Wilde used aesthetic decorations during his youth. This aspect of the movement was also satirised by Punch magazine and in Patience.

In 1882 Oscar Wilde visited Canada, where he toured the town of Woodstock, Ontario and gave a lecture on 29 May titled "The House Beautiful".[17] In this lecture Wilde exposited the principles of the Aesthetic Movement in decorative and applied design, also known at the time as the "Ornamental Aesthetic" style, according to which local flora and fauna were celebrated as beautiful and textured, layered ceilings were popular. An example of this can be seen in Annandale National Historic Site, located in Tillsonburg, Ontario, Canada. The house was built in 1880 and decorated by Mary Ann Tillson, who happened to attend Oscar Wilde's lecture in Woodstock. Since the Aesthetic Movement was only prevalent in the decorative arts from about 1880 until about 1890, there are not many surviving examples of this particular style but one such example is 18 Stafford Terrace, London, England, which provides an insight into how the middle classes interpreted its principles. Olana, the home of Frederic Edwin Church in upstate New York, is an important example of exoticism in the Aesthetic Movement decorative arts.[18]

Influence on advertising

[edit]The aesthetic movement in England became directly involved in advertising, and Pears soap (under advertising pioneer Thomas J. Barratt) recruited English actress and socialite Lillie Langtry—who had been painted by aesthete artists and was also a friend of Oscar Wilde—to promote their products in 1882, making her the first celebrity to endorse a commercial product.[19][20][21]

See also

[edit]- Aesthetics

- Arts and Crafts movement

- Aestheticization of politics

- Aestheticization of violence

- Ideasthesia

References

[edit]- ^ Fargis, Paul (1998). The New York Public Library Desk Reference – 3rd Edition. Macmillan General Reference. pp. 261. ISBN 0-02-862169-7.

- ^ Denney, Colleen. "At the Temple of Art: the Grosvenor Gallery, 1877–1890", Issue 1165, p. 38, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2000 ISBN 0-8386-3850-3.

- ^ a b "Aestheticism and decadence". British Library. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "The Aesthetic Movement". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Aesthetic Movement". Tate. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ ap Roberts, Ruth (1991). "Carlyle and the Aesthetic Movement". Carlyle Annual (12): 57–64. ISSN 1050-3099. JSTOR 44945538.

- ^ Angela Leighton (2007), p. 32.

- ^ Raeper, William (1987) George MacDonald, p. 183. Tring, Herts., and Batavia, Illinois: Lion Publishing.

- ^ McMullen, Lorraine (1971). An Introduction to the Aesthetic Movement in English Literature. Ottawa, Ontario: Bytown Press. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Welland, Dennis S. R. (1953). The Pre-Raphaelites in Literature and Art. London, UK: George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd. p. 22.

- ^ Mendelssohn, Michèle (2007). Henry James, Oscar Wilde and Aesthetic Culture. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 22–30. ISBN 978-0748623853.

- ^ "The Aesthetic Movement (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ "Aestheticism | Oscar Wilde, Decadence & Symbolism | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ Duggan, Bob (6 November 2011). "Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Painter, Poet, Sexual Revolutionary?". Big Think. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ Christopher Dresser. The Art of Decorative Design 1862.

- ^ Shindler, Michael (2 March 2020). "The Art of Madness and Mystery". Church Life Journal. The McGrath Institute for Church Life, University of Notre Dame. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ O'brien (1982), p. 114.

- ^ Burke, Doreen Bolger (1986). In Pursuit of Beauty: Americans and the Aesthetic Movement. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 20. ISBN 9780870994685.

- ^ Fortunato, Paul (2013). Modernist Aesthetics and Consumer Culture in the Writings of Oscar Wilde. Routledge. p. 33.

- ^ Jones, Geoffrey (2010). Beauty Imagined: A History of the Global Beauty Industry. Oxford University Press. p. 81.

- ^ "When Celebrity Endorsers Go Bad". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

British actress Lillie Langtry became the world's first celebrity endorser when her likeness appeared on packages of Pears Soap.

Sources

[edit]- Denisoff, Dennis. "Decadence and aestheticism." Cambridge Companion to the Fin de Siecle. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2007.

- Gal, Michalle. Aestheticism: Deep Formalism and the Emergence of Modernist Aesthetics. Peter Lang AG International Academic Publishers, 2015.

- Gaunt, William. The Aesthetic Adventure. New York: Harcourt, 1945. ISBN None.

- Halen, Widar. Christopher Dresser, a Pioneer of Modern Design. Phaidon: 1990. ISBN 0-7148-2952-8.

- Lambourne, Lionel. The Aesthetic Movement. Phaidon Press: 1996. ISBN 0-7148-3000-3.

- O'Brien, Kevin. Oscar Wilde in Canada, an apostle for the arts. Personal Library, Publishers: 1982.

- Snodin, Michael and John Styles. Design & The Decorative Arts, Britain 1500–1900. V&A Publications: 2001. ISBN 1-85177-338-X.

- Christopher Morley. "'Reform and Eastern Art' in Decorative Arts Society Journal", 2010.

- Gal, Michalle. "Aestheticism, philosophical critique". in Oxford Encyclopedia of Aesthetics (Michael Kelly, ed.). Oxford University Press, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Fiell, Charlotte; Fiell, Peter (2005). Design of the 20th Century (25th anniversary ed.). Köln: Taschen. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9783822840788. OCLC 809539744.

External links

[edit]- Gal, Michalle. "Aestheticism, philosophical critique". in Oxford Encyclopedia of Aesthetics (2nd edition, Michael Kelly, ed.).

- Aesthetes & Decadents on Victorian Web

- Annandale National Historic Site

- Books, Research & Information

- "Aestheticism Style Guide". British Galleries. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Edward Burne-Jones, Victorian artist-dreamer, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art