Howard Hughes

Howard Hughes | |

|---|---|

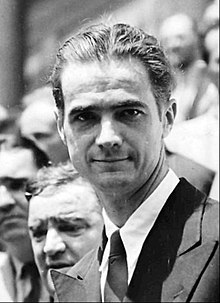

Hughes in 1938 | |

| Born | Howard Robard Hughes Jr. December 24, 1905 Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | April 5, 1976 (aged 70) Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Resting place | Glenwood Cemetery |

| Alma mater | California Institute of Technology Rice University (dropped out in 1924)[1] |

| Occupation(s) | Aerospace engineer, business magnate, film producer, investor, philanthropist, pilot |

| Years active | 1926–1976 |

| Title | Chairman and CEO of Summa Corporation Founder of The Howard Hughes Corporation Founder of the Hughes Aircraft Company Founder and benefactor of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Owner of Hughes Airwest Airlines |

| Board member of | Hughes Aircraft Company Howard Hughes Medical Institute |

| Spouses | |

| Parent(s) | Howard R. Hughes Sr. (father) Allene Stone Gano (mother) |

| Relatives | John Gano (ancestor) Rupert Hughes (uncle) Wright brothers (distant cousins) |

| Awards | Harmon Trophy (1936, 1938) Collier Trophy (1938) Congressional Gold Medal (1939) Octave Chanute Award (1940) National Aviation Hall of Fame (1973) |

| Aviation career | |

| Famous flights | Hughes H-1 Racer, Transcontinental airspeed record from Los Angeles to Newark NJ (1937), round the world airspeed record (1938) |

| Signature | |

Howard Robard Hughes Jr. (December 24, 1905 – April 5, 1976) was an American aerospace engineer, business magnate, film producer, investor, philanthropist and aircraft pilot.[2] He was best known during his lifetime as one of the richest and most influential people in the world. He first became prominent as a film producer, and then as an important figure in the aviation industry. Later in life, he became known for his eccentric behavior and reclusive lifestyle—oddities that were caused in part by his worsening obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), chronic pain from a near-fatal plane crash, and increasing deafness.

As a film tycoon, Hughes gained fame in Hollywood beginning in the late 1920s, when he produced big-budget and often controversial films such as The Racket (1928),[3] Hell's Angels (1930),[4] and Scarface (1932). He later acquired the RKO Pictures film studio in 1948, recognized then as one of the Big Five studios of Hollywood's Golden Age, although the production company struggled under his control and ultimately ceased operations in 1957.

Through his interest in aviation and aerospace travel, Hughes formed the Hughes Aircraft Company in 1932, hiring numerous engineers, designers, and defense contractors.[5][6]: 163, 259 He spent the rest of the 1930s and much of the 1940s setting multiple world air speed records and building the Hughes H-1 Racer (1935) and the gigantic H-4 Hercules (the Spruce Goose, 1947), the largest flying boat in history with the longest wingspan of any aircraft from the time it was built until 2019. He acquired and expanded Trans World Airlines and later acquired Air West, renaming it Hughes Airwest. Hughes won the Harmon Trophy on two occasions (1936 and 1938), the Collier Trophy (1938), and the Congressional Gold Medal (1939) all for his achievements in aviation throughout the 1930s. He was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1973 and was included in Flying magazine's 2013 list of the 51 Heroes of Aviation, ranked at No. 25.[7]

During his final years, Hughes extended his financial empire to include several major businesses in Las Vegas, such as real estate, hotels, casinos, and media outlets. Known at the time as one of the most powerful men in the state of Nevada, he is largely credited with transforming Las Vegas into a more refined cosmopolitan city. After years of mental and physical decline, Hughes died of kidney failure in 1976. His legacy is maintained through the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Howard Hughes Holdings Inc.[8]

Early life

[edit]

Howard Robard Hughes Jr. was the only child of Allene Stone Gano (1883–1922) and of Howard R. Hughes Sr. (1869–1924), a successful inventor and businessman from Missouri. He had English, Welsh and some French Huguenot ancestry,[9] and was a descendant of John Gano (1727–1804), the minister who allegedly baptized George Washington.[10] Through John Gano's sister Sussanah, Hughes was a 5th cousin once-removed of the Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur, who invented the first successful airplane.[11]

Hughes Sr. patented the two-cone roller bit in 1909, which allowed rotary drilling for petroleum in previously inaccessible places. The senior Hughes made the shrewd and lucrative decision to commercialize the invention by leasing the bits instead of selling them, obtaining several early patents, and founding the Hughes Tool Company in 1909.

Hughes' uncle was the famed novelist, screenwriter, and film director Rupert Hughes.[12]

A 1941 affidavit birth certificate of Hughes, signed by his aunt Annette Gano Lummis and by Estelle Boughton Sharp, states that he was born on December 24, 1905, in Harris County, Texas.[N 1] However, his certificate of baptism, recorded on October 7, 1906, in the parish register of St. John's Episcopal Church in Keokuk, Iowa, listed his date of birth as September 24, 1905, without any reference to the place of birth.[N 2]

At a young age, Hughes Jr. showed interest in science and technology. In particular, he had a great engineering aptitude, and built Houston's first "wireless" radio transmitter at age 11.[13] He went on to be one of the first licensed ham-radio operators in Houston, having the assigned callsign W5CY (originally 5CY).[14] At 12, Hughes was photographed for the local newspaper, which identified him as the first boy in Houston to have a "motorized" bicycle, which he had built from parts of his father's steam engine.[15] He was an indifferent student, with a liking for mathematics, flying, and mechanics. He took his first flying lesson at 14, and attended Fessenden School in Massachusetts in 1921.

After a brief stint at The Thacher School, Hughes attended math and aeronautical engineering courses at Caltech.[13][15] The red-brick house where Hughes lived as a teenager at 3921 Yoakum Blvd., Houston, still stands, now known as Hughes House on the grounds of the University of St. Thomas.[16][17]

His mother Allene died in March 1922 from complications of an ectopic pregnancy. Howard Hughes Sr. died of a heart attack in 1924. Their deaths apparently inspired Hughes to include the establishment of a medical research laboratory in the will that he signed in 1925 at age 19. Howard Sr.'s will had not been updated since Allene's death, and Hughes Jr. inherited 75% of the family fortune.[18] On his 19th birthday, Hughes was declared an emancipated minor, enabling him to take full control of his life.[19]

From a young age, Hughes became a proficient and enthusiastic golfer. He often scored near-par figures, playing the game to a two-three handicap during his 20s, and for a time aimed for a professional golf career. He golfed frequently with top players, including Gene Sarazen. Hughes rarely played competitively and gradually gave up his passion for the sport to pursue other interests.[20]

Hughes played golf every afternoon at LA courses including the Lakeside Golf Club, Wilshire Country Club, or the Bel-Air Country Club. Partners included George Von Elm or Ozzie Carlton. After Hughes hurt himself in the late 1920s, his golfing tapered off, and after his XF-11 crash, Hughes was unable to play at all.[6]: 56–57, 73, 196

Hughes withdrew from Rice University shortly after his father's death. On June 1, 1925, he married Ella Botts Rice, daughter of David Rice and Martha Lawson Botts of Houston, and great-niece of William Marsh Rice, for whom Rice University was named. They moved to Los Angeles, where he hoped to make a name for himself as a filmmaker.

They moved into the Ambassador Hotel, and Hughes proceeded to learn to fly a Waco, while simultaneously producing his first motion picture, Swell Hogan.[6]

Business career

[edit]Hughes enjoyed a highly successful business career beyond engineering, aviation and filmmaking; many of his career endeavors involved varying entrepreneurial roles.

Entertainment

[edit]Ralph Graves persuaded Hughes to finance a short film, Swell Hogan, which Graves had written and would star in. Hughes himself produced it. When he screened it, he thought it was a disaster. After hiring a film editor to try to salvage it, he finally ordered that it be destroyed.[21] His next two films, Everybody's Acting (1926) and Two Arabian Knights (1927), achieved financial success; the latter won the first Academy Award for Best Director of a comedy picture.[6]: 45–46 The Racket (1928) and The Front Page (1931) were also nominated for Academy Awards.

Hughes spent $3.5 million to make the flying film Hell's Angels (1930).[6]: 52, 126 Hell's Angels received one Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography.

He produced another hit, Scarface (1932), a production delayed by censors' concern over its violence.[6]: 128

The Outlaw premiered in 1943, but was not released nationally until 1946. The film featured Jane Russell, who received considerable attention from industry censors, this time owing to her revealing costumes.[6]: 152–160

RKO

[edit]

From the 1940s to the late 1950s, the Hughes Tool Company ventured into the film industry when it obtained partial ownership of the RKO companies, which included RKO Pictures, RKO Studios, a chain of movie theaters known as RKO Theatres and a network of radio stations known as the RKO Radio Network.

In 1948, Hughes gained control of RKO, a struggling major Hollywood studio, by acquiring the 929,000 shares owned by Floyd Odlum's Atlas Corporation, for $8,825,000 ($107,165,160 in 2023). Within weeks of acquiring the studio, Hughes dismissed 700 employees. Production dwindled to 9 pictures during the first year of Hughes' control; previously RKO had averaged 30 per year.[6]: 234–237

That same year, 1948, he was able to arrange for his previous films with United Artists (UA), The Outlaw, Mad Wednesday, and Vendetta to be transferred to RKO. In exchange for the three completed being removed from UA distribution, Hughes and James and Theodore Nasser of General Service Studios would provide the financing of three independent films for distribution by UA. In terms of negotiations directly with RKO, the company agree to remove the production of the film Jet Pilot from David O. Selznick to Hughes.[22] Hughes produced the film during the years 1949-1950 and owned RKO and in turn the distribution for the film. However, the film was not released until 1957 by Universal Pictures due in part to the subsequent events that would take place at RKO Distribution, and largely due the extra aerial film footage that had been filmed over the years after the film's 1950 completion. Hughes was undertaking a final edit before the 1957 release.[23]

After his acquisition of RKO, Hughes shut down production at the studio for six months, during which time he ordered investigations into the political leanings of every remaining RKO employee. Only after ensuring that the stars under contract to RKO had no suspect affiliations would Hughes approve completed pictures to be sent back for re-shooting. This was especially true of the women under contract to RKO at that time. If Hughes felt that his stars did not properly represent the political views of his liking or if a film's anti-communist politics were not sufficiently clear, he pulled the plug. In 1952, an abortive sale to a Chicago-based five-man syndicate, two of whom had a history of complaints about their business practices and none with any experience in the movie industry, disrupted studio operations at RKO even further.[24]

In 1953, Hughes became involved with a high-profile lawsuit as part of the settlement of the United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. Antitrust Case. As a result of the hearings, the shaky status of RKO became increasingly apparent. A steady stream of lawsuits from RKO's minority shareholders had grown to become extremely annoying to Hughes. They had accused him of financial misconduct and corporate mismanagement. Since Hughes wanted to focus primarily on his aircraft manufacturing and TWA holdings during the years of the Korean War of 1950 to 1953, Hughes offered to buy out all other RKO stockholders in order to dispense with their distractions[citation needed].

By the end of 1954, Hughes had gained near-total control of RKO at a cost of nearly $24 million, becoming the first sole owner of a major Hollywood studio since the silent-film era. Six months later Hughes sold the studio to the General Tire and Rubber Company for $25 million. Hughes retained the rights to pictures that he had personally produced, including those made at RKO. He also retained Jane Russell's contract. For Howard Hughes, this was the virtual end of his 25-year involvement in the motion-picture industry. However, his reputation as a financial wizard emerged unscathed. During that time period, RKO became known as the home of classic film noir productions, thanks in part to the limited budgets required to make such films during Hughes' tenure. Hughes reportedly walked away from RKO having made $6.5 million in personal profit.[25] According to Noah Dietrich, Hughes made a $10,000,000 profit from the sale of the theaters and made a profit of $1,000,000 from his 7-year ownership of RKO.[6]: 272–273

Real estate

[edit]According to Noah Dietrich, "Land became a principal asset for the Hughes empire". Hughes acquired 1200 acres in Culver City for Hughes Aircraft, bought 7 sections [4,480 acres] in Tucson for his Falcon missile-plant, and purchased 25,000 acres near Las Vegas.[6]: 103, 254 In 1968, the Hughes Tool Company purchased the North Las Vegas Air Terminal.

Originally known as Summa Corporation, the Howard Hughes Corporation formed in 1972 when the oil-tools business of Hughes Tool Company, then owned by Howard Hughes Jr., floated on the New York Stock Exchange under the "Hughes Tool" name. This forced the remaining businesses of the "original" Hughes Tool to adopt a new corporate name: "Summa". The name "Summa"—Latin for "highest"—was adopted without the approval of Hughes himself, who preferred to keep his own name on the business, and suggested "HRH Properties" (for Hughes Resorts and Hotels, and also his own initials). In 1988 Summa announced plans for Summerlin, a master-planned community named for the paternal grandmother of Howard Hughes, Jean Amelia Summerlin.[26]

Initially staying in the Desert Inn, Hughes refused to vacate his room, and instead decided to purchase the entire hotel. Hughes extended his financial empire to include Las Vegas real estate, hotels, and media outlets, spending an estimated $300 million, and using his considerable powers to acquire many of the well-known hotels, especially the venues connected with organized crime. He quickly became one of the most powerful men in Las Vegas. He was instrumental in changing the image of Las Vegas from its Wild West and, later, Mafia / organized crime roots into a more refined cosmopolitan city.[27] In addition to the Desert Inn, Hughes would eventually own the Sands, Frontier, Silver Slipper, Castaways, and Landmark and Harold's Club in Reno. During his four years in Las Vegas, Hughes became the largest employer in Nevada.[27]

Aviation and aerospace

[edit]

Another portion of Hughes' commercial interests involved aviation, airlines, and the aerospace and defense industries. A lifelong aircraft enthusiast and pilot, Hughes survived four airplane accidents: one in a Thomas-Morse Scout while filming Hell's Angels, one while setting the airspeed record in the Hughes Racer, one at Lake Mead in 1943, and the near-fatal crash of the Hughes XF-11 in 1946. At Rogers Airport in Los Angeles, he learned to fly from pioneer aviators, including Moye Stephens and J.B. Alexander. He set many world records and commissioned the construction of custom aircraft for himself while heading Hughes Aircraft at the airport in Glendale, CA. Operating from there, the most technologically important aircraft he commissioned was the Hughes H-1 Racer. On September 13, 1935, Hughes, flying the H-1, set the landplane airspeed record of 352 mph (566 km/h) over his test course near Santa Ana, California (Giuseppe Motta reaching 362 mph in 1929 and George Stainforth reached 407.5 mph in 1931, both in seaplanes). This marked the last time in history that an aircraft built by a private individual set the world airspeed record. A year and a half later, on January 19, 1937, flying the same H-1 Racer fitted with longer wings, Hughes set a new transcontinental airspeed record by flying non-stop from Los Angeles to Newark in seven hours, 28 minutes, and 25 seconds (beating his own previous record of nine hours, 27 minutes). His average ground-speed over the flight was 322 mph (518 km/h).[28][6]: 69–72, 131–135

The H-1 Racer featured a number of design innovations: it had retractable landing gear (as Boeing Monomail had five years before), and all rivets and joints set flush into the body of the aircraft to reduce drag. The H-1 Racer is thought to have influenced the design of a number of World War II fighters such as the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, Focke-Wulf Fw 190, and F8F Bearcat,[29] although that has never been reliably confirmed. In 1975 the H-1 Racer was donated to the Smithsonian.[6]: 131–135

Hughes Aircraft

[edit]

In 1932 Hughes founded the Hughes Aircraft Company, a division of Hughes Tool Company, in a rented corner of a Lockheed Aircraft Corporation hangar in Burbank, California, to build the H-1 racer.

Shortly after founding the company, Hughes used the alias "Charles Howard" to accept a job as a baggage handler for American Airlines. He was soon promoted to co-pilot. Hughes continued to work for American Airlines until his real identity was discovered.[30][31][32]

During and after World War II Hughes turned his company into a major defense contractor. The Hughes Helicopters division started in 1947 when helicopter manufacturer Kellett sold their latest design to Hughes for production. Hughes Aircraft became a major U.S. aerospace- and defense contractor, manufacturing numerous technology-related products that included spacecraft vehicles, military aircraft, radar systems, electro-optical systems, the first working laser, aircraft computer systems, missile systems, ion-propulsion engines (for space travel), commercial satellites, and other electronics systems.[33][34][35]

In 1948 Hughes created a new division of Hughes Aircraft: the Hughes Aerospace Group. The Hughes Space and Communications Group and the Hughes Space Systems Division were later spun off in 1948 to form their own divisions and ultimately became the Hughes Space and Communications Company in 1961. In 1953 Howard Hughes gave all his stock in the Hughes Aircraft Company to the newly formed Howard Hughes Medical Institute, thereby turning the aerospace and defense contractor into a tax-exempt charitable organization. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute sold Hughes Aircraft in 1985 to General Motors for $5.2 billion. In 1997 General Motors sold Hughes Aircraft to Raytheon and in 2000, sold Hughes Space & Communications to Boeing. A combination of Boeing, GM, and Raytheon acquired the Hughes Research Laboratories, which focused on advanced developments in microelectronics, information & systems sciences, materials, sensors, and photonics; their work-space spans from basic research to product delivery. It has particularly emphasized capabilities in high-performance integrated circuits, high-power lasers, antennas, networking, and smart materials.

Round-the-world flight

[edit]On July 14, 1938, Hughes set another record by completing a flight around the world in just 91 hours (three days, 19 hours, 17 minutes),[36] beating the previous record of 186 hours (seven days, 18 hours, 49 minutes) set in 1933 by Wiley Post in a single-engine Lockheed Vega by almost four days. Hughes returned home ahead of photographs of his flight. Taking off from New York City, Hughes continued to Paris, Moscow, Omsk, Yakutsk, Fairbanks, and Minneapolis, then returning to New York City. For this flight he flew a Lockheed 14 Super Electra (NX18973, a twin-engine transport with a crew of four) fitted with the latest radio and navigational equipment. Harry Connor was the co-pilot, Thomas Thurlow the navigator, Richard Stoddart the engineer, and Ed Lund the mechanic. Hughes wanted the flight to be a triumph of U.S. aviation technology, illustrating that safe, long-distance air travel was possible. Albert Lodwick of Mystic, Iowa, provided organizational skills as the flight operations manager.[37] While Hughes had previously been relatively obscure despite his wealth, better known for dating Katharine Hepburn, New York City now gave him a ticker-tape parade in the Canyon of Heroes.[38][6]: 136–139 Hughes and his crew were awarded the 1938 Collier Trophy for flying around the world in record time.[39][40] He was awarded the Harmon Trophy in 1936[41] and 1938 for the record-breaking global circumnavigation.[42]

In 1938 the William P. Hobby Airport in Houston, Texas—known at the time as Houston Municipal Airport—was renamed after Hughes, but the name was changed back due to public outrage over naming the airport after a living person. Hughes also had a role in the financing of the Boeing 307 Stratoliner for TWA, and the design and financing of the Lockheed L-049 Constellation.[5]

Other aviator awards include: the Bibesco Cup of the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale in 1938, the Octave Chanute Award in 1940, and a special Congressional Gold Medal in 1939 "in recognition of the achievements of Howard Hughes in advancing the science of aviation and thus bringing great credit to his country throughout the world".[43][44]

President Harry S. Truman sent the Congressional medal to Hughes after the F-11 crash. After his around-the-world flight, Hughes had declined to go to the White House to collect it.[6]: 196

Hughes D-2

[edit]Development of the D-2 began around 1937, but little is known about its early gestation because Hughes' archives on the aircraft have not been made public. Aircraft historian René Francillon speculates that Hughes designed the aircraft for another circumnavigation record attempt, but the outbreak of World War II closed much of the world's airspace and made it difficult to buy aircraft parts without government approval, so he decided to sell the aircraft to the U.S. Army instead. In December 1939, Hughes proposed that the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) procure it as a "pursuit type airplane"[45] (i.e. a fighter aircraft). It emerged as a two or three-seat twin-boom aircraft powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-2800-49 engines and constructed mostly of Duramold, a type of molded plywood.[46] The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF, successor to the USAAC) struggled to define a mission for the D-2, which lacked both the maneuverability of a fighter and the payload of a bomber, and was highly skeptical of the extensive use of plywood; however, the project was kept alive by high-level intervention from General Henry H. Arnold.[47] The prototype was brought to Harper's Dry Lake in California in great secrecy in 1943 and first flew on June 20 of that year.[48][49] The initial test flights revealed serious flight control problems, so the D-2 returned to the hangar for extensive changes to its wings, and Hughes proposed to redesignate it as the D-5.[49] However, in November 1944, the still-incomplete D-2 was destroyed in a hangar fire reportedly caused by a lightning strike.[50]

Fatal crash of the Sikorsky S-43

[edit]

In the spring of 1943 Hughes spent nearly a month in Las Vegas, test-flying his Sikorsky S-43 amphibious aircraft, practicing touch-and-go landings on Lake Mead in preparation for flying the H-4 Hercules. The weather conditions at the lake during the day were ideal and he enjoyed Las Vegas at night. On May 17, 1943, Hughes flew the Sikorsky from California, carrying two Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) aviation inspectors, two of his employees, and actress Ava Gardner. Hughes dropped Gardner off in Las Vegas and proceeded to Lake Mead to conduct qualifying tests in the S-43. The test flight did not go well. The Sikorsky crashed into Lake Mead, killing CAA inspector Ceco Cline and Hughes' employee Richard Felt. Hughes suffered a severe gash on the top of his head when he hit the upper control panel and had to be rescued by one of the others on board.[51] Hughes paid divers $100,000 to raise the aircraft and later spent more than $500,000 restoring it.[52] Hughes sent the plane to Houston, where it remained for many years.[6]: 186

Hughes XF-11

[edit]Acting on a recommendation of the president's son, Colonel Elliott Roosevelt, who had become friends with Hughes, in September 1943 General Arnold issued a directive to order 100 of a reconnaissance development of the D-2, known as the F-11 (XF-11 in prototype form).[53] The project was controversial from the beginning, as the USAAF Air Materiel Command deeply doubted that Hughes Aircraft could fulfill a contract this large, but Arnold pushed the project forward. Materiel Command demanded a host of major design changes notably including the elimination of Duramold; Hughes, who sought $3.9 million in reimbursement for sunk costs from the D-2, strenuously objected because this undercut his argument that the XF-11 was a modified D-2 rather than a new design. Protracted negotiations caused months of delays but ultimately yielded few design concessions.[54] The war ended before the first XF-11 prototype was completed and the F-11 production contract was canceled. The XF-11 emerged in 1946 as an all-metal, twin-boom, three-seat reconnaissance aircraft, substantially larger than the D-2 and powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-4360-31 engines, each driving a set of contra-rotating propellers.[54] Only two prototypes were completed; the second one had a conventional single propeller per side.[55][56]

Near-fatal crash of the XF-11

[edit]Hughes was almost killed on July 7, 1946, while performing the first flight of the XF-11 near Hughes Airfield at Culver City, California. Hughes extended the test flight well beyond the 45-minute limit decreed by the USAAF, possibly distracted by landing gear retraction problems.[57] An oil leak caused one of the contra-rotating propellers to reverse pitch, causing the aircraft to yaw sharply and lose altitude rapidly. Hughes attempted to save the aircraft by landing it at the Los Angeles Country Club golf course, but just seconds before reaching the course, the XF-11 started to drop dramatically and crashed in the Beverly Hills neighborhood surrounding the country club.[58][59]

When the XF-11 finally came to a halt after destroying three houses, the fuel tanks exploded, setting fire to the aircraft and a nearby home at 808 North Whittier Drive owned by Charles E. Meyer.[60] Hughes managed to pull himself out of the flaming wreckage but lay beside the aircraft until he was rescued by U.S. Marine Corps Master Sergeant William L. Durkin, who happened to be in the area visiting friends.[61] Hughes sustained significant injuries in the crash, including a crushed collar bone, multiple cracked ribs,[62] crushed chest with collapsed left lung, shifting his heart to the right side of the chest cavity, and numerous third-degree burns.[63][64][65][66] An oft-told story said that Hughes sent a check to the Marine weekly for the remainder of his life as a sign of gratitude. Noah Dietrich asserted that Hughes did send Durkin $200 a month, but Durkin's daughter denied knowing that he received any money from Hughes.[6]: 197 [67]

Despite his physical injuries, Hughes took pride that his mind was still working. As he lay in his hospital bed, he decided that he did not like the bed's design. He called in plant engineers to design a customized bed, equipped with hot and cold running water, built in six sections, and operated by 30 electric motors, with push-button adjustments.[68] Hughes designed the hospital bed specifically to alleviate the pain caused by moving with severe burn injuries. He never used the bed that he designed.[69] Hughes' doctors considered his recovery almost miraculous.

Many attribute his long-term dependence on opiates to his use of codeine as a painkiller during his convalescence.[70] Yet Dietrich asserts that Hughes recovered the "hard way—no sleeping pills, no opiates of any kind".[6]: 195 The trademark mustache he wore afterward hid a scar on his upper lip resulting from the accident.[71]

H-4 Hercules

[edit]

The War Production Board, a civilian government agency that supervised war production from 1942-45, originally contracted with Henry Kaiser and Hughes to produce the gigantic HK-1 Hercules flying boat for use during World War II to transport troops and equipment across the Atlantic as an alternative to seagoing troop transport ships that were vulnerable to German U-boats. The military services opposed the project, thinking it would siphon resources from higher-priority programs, but Hughes' powerful allies in Washington, D.C. advocated it. After disputes, Kaiser withdrew from the project and Hughes elected to continue it as the H-4 Hercules. However, the aircraft was not completed until after World War II.[72][73]

The Hercules was the world's largest flying boat, the largest aircraft made from wood,[74] and, at 319 feet 11 inches (97.51 m), had the longest wingspan of any aircraft (the next-largest wingspan was about 310 ft (94 m)). (The Hercules is no longer the longest nor heaviest aircraft ever built - surpassed by the Antonov An-225 Mriya produced in 1985.)

The Hercules flew only once for one mile (1.6 km), and 70 feet (21 m) above the water, with Hughes at the controls, on November 2, 1947.[75][6]: 209–210

Critics nicknamed the Hercules the Spruce Goose, but it was actually made largely from birch (not spruce) rather than from aluminum, because the contract required that Hughes build the aircraft of "non-strategic materials". It was built in Hughes' Westchester, California, facility. In 1947, Howard Hughes was summoned to testify before the Senate War Investigating Committee to explain why the H-4 development had been so troubled, and why $22 million had produced only two prototypes of the XF-11. General Elliott Roosevelt and numerous other USAAF officers were also called to testify in hearings that transfixed the nation during August and November 1947.[citation needed] In hotly-disputed testimony over TWA's route awards and malfeasance in the defense-acquisition process, Hughes turned the tables on his main interlocutor, Maine senator Owen Brewster, and the hearings were widely interpreted[by whom?] as a Hughes victory. After being displayed at the harbor of Long Beach, California, the Hercules was moved to McMinnville, Oregon, where as of 2020[update] it features at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum.[76][6]: 198–208

On November 4, 2017, the 70th anniversary of the only flight of the H-4 Hercules was celebrated at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum with Hughes' paternal cousin Michael Wesley Summerlin and Brian Palmer Evans, son of Hughes radio technology pioneer Dave Evans, taking their positions in the recreation of a photo that was previously taken of Hughes, Dave Evans, and Joe Petrali on board the H-4 Hercules.[77]

Airlines

[edit]In 1939, at the urging of Jack Frye, president of Transcontinental & Western Airlines, the predecessor of Trans World Airlines (TWA), Hughes began to quietly purchase a majority share of TWA stock (78% of stock, to be exact); he took a controlling interest in the airline by 1944.[78] Although he never had an official position with TWA, Hughes handpicked the board of directors, which included Noah Dietrich, and often issued orders directly to airline staff.[78][79] Hughes Tool Co. purchased the first six Stratoliners Boeing manufactured. Hughes used one personally, and he let TWA operate the other five.[6]: 11, 145–148

Hughes is commonly credited as the driving force behind the Lockheed Constellation airliner, which Hughes and Frye ordered in 1939 as a long-range replacement for TWA's fleet of Boeing 307 Stratoliners. Hughes personally financed TWA's acquisition of 40 Constellations for $18 million, the largest aircraft order in history up to that time. The Constellations were among the highest-performing commercial aircraft of the late 1940s and 1950s and allowed TWA to pioneer nonstop transcontinental service.[80] During World War II Hughes leveraged political connections in Washington to obtain rights for TWA to serve Europe, making it the only U.S. carrier with a combination of domestic and transatlantic routes.[78]

After the announcement of the Boeing 707, Hughes opted to pursue a more advanced jet aircraft for TWA and approached Convair in late 1954. Convair proposed two concepts to Hughes, but Hughes was unable to decide which concept to adopt, and Convair eventually abandoned its initial jet project after the mockups of the 707 and Douglas DC-8 were unveiled.[81] Even after competitors such as United Airlines, American Airlines and Pan American World Airways had placed large orders for the 707, Hughes only placed eight orders for 707s through the Hughes Tool Company and forbade TWA from using the aircraft.[79] After finally beginning to reserve 707 orders in 1956, Hughes embarked on a plan to build his own "superior" jet aircraft for TWA, applied for CAB permission to sell Hughes aircraft to TWA, and began negotiations with the state of Florida to build a manufacturing plant there. However, he abandoned this plan around 1958, and in the interim, negotiated new contracts for 707 and Convair 880 aircraft and engines totaling $400 million.[82]

The financing of TWA's jet orders precipitated the end of Hughes' relationship with Noah Dietrich, and ultimately Hughes' ouster from control of TWA. Hughes did not have enough cash on hand or future cash flow to pay for the orders and did not immediately seek bank financing. Hughes' refusal to heed Dietrich's financing advice led to a major rift between the two by the end of 1956. Hughes believed that Dietrich wished to have Hughes committed as mentally incompetent, although the evidence of this is inconclusive. Dietrich resigned by telephone in May 1957 after repeated requests for stock options, which Hughes refused to grant, and with no further progress on the jet financing.[83] As Hughes' mental state worsened, he ordered various tactics to delay payments to Boeing and Convair; his behavior led TWA's banks to insist that he be removed from management as a condition for further financing.[79]

In 1960, Hughes was ultimately forced out of the management of TWA, although he continued to own 78% of the company. In 1961, TWA filed suit against Hughes Tool Company, claiming that the latter had violated antitrust law by using TWA as a captive market for aircraft trading. The claim was largely dependent upon obtaining testimony from Hughes himself. Hughes went into hiding and refused to testify. A default judgment was issued against Hughes Tool Company for $135 million in 1963 but was overturned by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1973,[84] on the basis that Hughes was immune from prosecution.[85] In 1966, Hughes was forced to sell his TWA shares. The sale of his TWA shares brought Hughes $546,549,771.[6]: 299–300

Hughes acquired control of Boston-based Northeast Airlines in 1962. However, the airline's lucrative route authority between major northeastern cities and Miami was terminated by a CAB decision around the time of the acquisition, and Hughes sold control of the company to a trustee in 1964. Northeast went on to merge with Delta Air Lines in 1972.[86]

In 1970, Hughes acquired San Francisco-based Air West and renamed it Hughes Airwest. Air West had been formed in 1968 by the merger of Bonanza Air Lines, Pacific Air Lines, and West Coast Airlines, all of which operated in the western U.S. By the late 1970s, Hughes Airwest operated an all-jet fleet of Boeing 727-200, Douglas DC-9-10, and McDonnell Douglas DC-9-30 jetliners serving an extensive route network in the western U.S. with flights to Mexico and western Canada as well.[87] By 1980, the airline's route system reached as far east as Houston (Hobby Airport) and Milwaukee with a total of 42 destinations being served.[87] Hughes Airwest was then acquired by and merged into Republic Airlines (1979–1986) in late 1980. Republic was subsequently acquired by and merged into Northwest Airlines which in turn was ultimately merged into Delta Air Lines in 2008.

Business with David Charnay

[edit]Hughes made numerous business partnerships through his friend, the industrialist and producer David Charnay,[88][89] beginning with their work on the film The Conqueror (1956).[90][91] Though the film made money at the box office, its themes, dialogue, and casting were ridiculed. It was shot in St. George, Utah, which had been badly affected by the testing of more than 100 nuclear bombs. Many of the cast and crew were later diagnosed with cancer, leading it to be called an "RKO Radioactive Picture". Hughes eventually bought every copy of the film he could, and is reported to have watched the film at home every night in the years before he died.[92]

Charnay later bought Four Star, the film and television production company that produced The Conqueror.[93][94]

Hughes and Charnay's most published dealings were with a contested AirWest leveraged buyout. Charnay led the buyout group that involved Howard Hughes and their partners acquiring Air West. Hughes, Charnay, as well as three others, were indicted.[95][96][97][98] The indictment, made by U.S. Attorney DeVoe Heaton, accused the group of conspiring to drive down the stock price of Air West in order to pressure company directors to sell to Hughes.[99][95] The charges were dismissed after a judge had determined that the indictment had failed to allege an illegal action on the part of Hughes, Charnay, and all the other accused in the indictment. Thompson, the federal judge that made the decision to dismiss the charges, called the indictment one of the worst claims that he had ever seen. The charges were filed a second time by U.S. Attorney DeVoe Heaton's assistant, Dean Vernon. The Federal Judge ruled on November 13, 1974, and elaborated to say that the case suggested a "reprehensible misuse of the power of great wealth," but in his judicial opinion, "no crime had been committed."[100][101][102] The aftermath of the Air West deal was later settled with the SEC by paying former stockholders for alleged losses from the sale of their investment in Air West stock.[103] As noted above, Air West was subsequently renamed Hughes Airwest. During a long pause between the years of the dismissed charges against Hughes, Charnay, and their partners, Howard Hughes mysteriously died mid-flight while on the way to Houston from Acapulco. No further attempts were made to file any indictments after Hughes died.[104][105][106]

Howard Hughes Medical Institute

[edit]In 1953, Hughes launched the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Miami (currently located in Chevy Chase, Maryland near Washington, D.C.), with the express goal of basic biomedical research, including trying to understand, in Hughes' words, the "genesis of life itself,"[citation needed] due to his lifelong interest in science and technology. Hughes' first will, which he signed in 1925 at the age of 19, stipulated that a portion of his estate should be used to create a medical institute bearing his name.[107] When a major battle with the IRS loomed ahead, Hughes gave all his stock in the Hughes Aircraft Company to the institute, thereby turning the aerospace and defense contractor into a for-profit entity of a fully tax-exempt charity. Hughes' internist, Verne Mason, who treated Hughes after his 1946 aircraft crash, was chairman of the institute's medical advisory committee.[108] The Howard Hughes Medical Institute's new board of trustees sold Hughes Aircraft in 1985 to General Motors for $5.2 billion, allowing the institute to grow dramatically.

In 1954, Hughes transferred Hughes Aircraft to the foundation, which paid Hughes Tool Co. $18,000,000 for the assets. The foundation leased the land from Hughes Tool Co., which then subleased it to Hughes Aircraft Corp. The difference in rent, $2,000,000 per year, became the foundation's working capital.[6]: 268

The deal was the topic of a protracted legal battle between Hughes and the Internal Revenue Service, which Hughes ultimately won. After his death in 1976, many thought that the balance of Hughes' estate would go to the institute, although it was ultimately divided among his cousins and other heirs, given the lack of a will to the contrary. The HHMI was the fourth largest private organization as of 2007[update] and one of the largest devoted to biological and medical research, with an endowment of $20.4 billion as of June 2018[update].[109]

Glomar Explorer and the taking of K-129

[edit]In 1972, during the Cold War era, Hughes was approached by the CIA through his longtime partner, David Charnay, to help secretly recover the Soviet submarine K-129, which had sunk near Hawaii four years earlier.[110] Hughes' involvement provided the CIA with a plausible cover story, conducting expensive civilian marine research at extreme depths and the mining of undersea manganese nodules. The recovery plan used the special-purpose salvage vessel Glomar Explorer. In the summer of 1974, Glomar Explorer attempted to raise the Soviet vessel.[111][112] However, during the recovery, a mechanical failure in the ship's grapple caused half of the submarine to break off and fall to the ocean floor. This section is believed to have held many of the most sought-after items, including its code book and nuclear missiles. Two nuclear-tipped torpedoes and some cryptographic machines were recovered, along with the bodies of six Soviet submariners who were subsequently given formal burial at sea in a filmed ceremony. The operation, known as Project Azorian (but incorrectly referred to by the press as Project Jennifer), became public in February 1975 after secret documents, obtained by burglars of Hughes' headquarters in June 1974, were released.[113] Although he lent his name and his company's resources to the operation, Hughes and his companies had no operational involvement in the project. The Glomar Explorer was eventually acquired by Transocean, and was sent to the scrap yard in 2015 during a large decline in oil prices.[114]

Personal life

[edit]Early romances

[edit]In 1929, Hughes' wife of four years, Ella, returned to Houston and filed for divorce.

Hughes dated many famous women, including Joan Crawford, Terry Moore,[115] Debra Paget, Billie Dove, Faith Domergue, Bette Davis, Yvonne De Carlo, Ava Gardner, Olivia de Havilland, Katharine Hepburn,[116] Hedy Lamarr, Ginger Rogers, Pat Sheehan,[117] Gloria Vanderbilt,[118] Mamie Van Doren and Gene Tierney.

He also proposed to Joan Fontaine several times, according to her autobiography No Bed of Roses. Jean Harlow accompanied him to the premiere of Hell's Angels, but Noah Dietrich wrote many years later that the relationship was strictly professional, as Hughes disliked Harlow personally. In his 1971 book, Howard: The Amazing Mr. Hughes, Dietrich said that Hughes genuinely liked and respected Jane Russell, but never sought romantic involvement with her. According to Russell's autobiography, however, Hughes once tried to bed her after a party. Russell (who was married at the time) refused him, and Hughes promised it would never happen again. The two maintained a professional and private friendship for many years. Hughes remained good friends with Tierney who, after his failed attempts to seduce her, was quoted as saying "I don't think Howard could love anything that did not have a motor in it". Later, when Tierney's daughter Daria was born deaf and blind and with a severe learning disability because of Tierney's exposure to rubella during her pregnancy, Hughes saw to it that Daria received the best medical care and paid all expenses.[119]

Luxury yacht

[edit]In 1933, Hughes made a purchase of a luxury steam yacht named the Rover, which was previously owned by Scottish shipping magnate James Mackay, 1st Earl of Inchcape. Hughes stated that "I have never seen the Rover but bought it on the blueprints, photographs and the reports of Lloyd's surveyors. My experience is that the English are the most honest race in the world."[120] Hughes renamed the yacht Southern Cross and later sold her to Swedish entrepreneur Axel Wenner-Gren.[121]

1936 automobile accident

[edit]On July 11, 1936, Hughes struck and killed a pedestrian named Gabriel S. Meyer with his car at the corner of 3rd Street and Lorraine in Los Angeles.[122] After the crash, Hughes was taken to the hospital and certified as sober, but an attending doctor made a note that Hughes had been drinking. A witness to the crash told police that Hughes was driving erratically and too fast and that Meyer had been standing in the safety zone of a streetcar stop. Hughes was booked on suspicion of negligent homicide and held overnight in jail until his attorney, Neil S. McCarthy, obtained a writ of habeas corpus for his release pending a coroner's inquest.[123][124] By the time of the coroner's inquiry, however, the witness had changed his story and claimed that Meyer had moved directly in front of Hughes' car. Nancy Bayly (Watts), who was in the car with Hughes at the time of the crash, corroborated this version of the story. On July 16, 1936, Hughes was held blameless by a coroner's jury at the inquest into Meyer's death.[125] Hughes told reporters outside the inquiry, "I was driving slowly and a man stepped out of the darkness in front of me".

Marriage to Jean Peters

[edit]On January 12, 1957, Hughes married actress Jean Peters at a small hotel in Tonopah, Nevada.[126][127] The couple met in the 1940s, before Peters became a film actress.[128] They had a highly publicized romance in 1947 and there was talk of marriage, but she said she could not combine it with her career.[129] Some later claimed that Peters was "the only woman [Hughes] ever loved",[130] and he reportedly had his security officers follow her everywhere even when they were not in a relationship. Such reports were confirmed by actor Max Showalter, who became a close friend of Peters while shooting Niagara (1953).[131] Showalter told an interviewer that because he frequently met with Peters, Hughes' men threatened to ruin his career if he did not leave her alone.[131]

Connections to Richard Nixon and Watergate

[edit]Shortly before the 1960 Presidential election, Richard Nixon was alarmed when it was revealed that his brother, Donald, had received a $205,000 loan from Hughes. It has long been speculated[132] that Nixon's drive to learn what the Democrats were planning in 1972 was based in part on his belief that the Democrats knew about a later bribe that his friend Bebe Rebozo had received from Hughes after Nixon took office.[133]

In late 1971, Donald Nixon was collecting intelligence for his brother in preparation for the upcoming presidential election. One of his sources was John H. Meier, a former business adviser of Hughes who had also worked with Democratic National Committee Chairman Larry O'Brien.[134]

Meier, in collaboration with former Vice President Hubert Humphrey and others, wanted to feed misinformation to the Nixon campaign. Meier told Donald that he was sure the Democrats would win the election because Larry O'Brien had a great deal of information on Richard Nixon's illicit dealings with Howard Hughes that had never been released;[135][136] O'Brien did not actually have any such information, but Meier wanted Nixon to think that he did. Donald told his brother that O'Brien was in possession of damaging information that could destroy his campaign.[137] Terry Lenzner, who was the chief investigator for the Senate Watergate Committee, speculates that it was Nixon's desire to know what O'Brien knew about Nixon's dealings with Hughes that may have partially motivated the Watergate break-in.[138]

Last years

[edit]Physical and mental decline

[edit]Hughes was widely considered eccentric[139] and suffered from severe obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).[140][141]

Dietrich wrote that Hughes always ate the same thing for dinner: a New York strip steak cooked medium rare, dinner salad, and peas, but only the smaller ones, pushing the larger ones aside. For breakfast, he wanted his eggs cooked the way his family cook, Lily, made them. Hughes had a "phobia about germs", and "his passion for secrecy became a mania."[6]: 58–62, 182–183

While directing The Outlaw, Hughes became fixated on a small flaw in one of Jane Russell's blouses, claiming that the fabric bunched up along a seam and gave the appearance of two nipples on each breast. He wrote a detailed memorandum to the crew on how to fix the problem. Richard Fleischer, who directed His Kind of Woman with Hughes as executive producer, wrote at length in his autobiography about the difficulty of dealing with the tycoon. In his book Just Tell Me When to Cry, Fleischer explained that Hughes was fixated on trivial details and was alternately indecisive and obstinate. He also revealed that Hughes' unpredictable mood swings made him wonder if the film would ever be completed.

In 1958, Hughes told his aides that he wanted to screen some movies at a film studio near his home. He stayed in the studio's darkened screening room for more than four months, never leaving. He ate only chocolate bars and chicken and drank only milk and was surrounded by dozens of boxes of Kleenex that he continuously stacked and re-arranged.[142] He wrote detailed memos to his aides giving them explicit instructions neither to look at him nor speak to him unless spoken to. Throughout this period, Hughes sat fixated in his chair, often naked, continuously watching movies. When he finally emerged in the summer of 1958, his hygiene was terrible. He had neither bathed nor cut his hair and nails for weeks; this may have been due to allodynia, which results in a pain response to stimuli that would normally not cause pain.[70]

After the screening room incident, Hughes moved into a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel where he also rented rooms for his aides, his wife, and numerous girlfriends. He would sit naked in his bedroom with a pink hotel napkin placed over his genitals, watching movies. This may have been because Hughes found the touch of clothing painful due to allodynia. He may have watched movies to distract himself from his pain—a common practice among patients with intractable pain, especially those who do not receive adequate treatment.[70] In one year, he spent an estimated $11 million at the hotel.

Hughes began purchasing restaurant chains and four-star hotels that had been founded within the state of Texas. This included, if for only a short period, many unknown franchises currently out of business. He placed ownership of the restaurants with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and all licenses were resold shortly after.[143][144]

He became obsessed with the 1968 film Ice Station Zebra, and had it run on a continuous loop in his home. According to his aides, he watched it 150 times.[145][146] Feeling guilty about the failure of his film The Conqueror, a commercial and critical flop, he bought every copy of the film for $12 million, watching the film on repeat. Paramount Pictures acquired the rights of the film in 1979, three years after his death.[147]

Hughes insisted on using tissues to pick up objects to insulate himself from germs. He would also notice dust, stains, or other imperfections on people's clothes and demand that they take care of them. Once one of the most visible men in America, Hughes ultimately vanished from public view, although tabloids continued to follow rumors of his behavior and whereabouts. He was reported to be terminally ill, mentally unstable, or even dead.[148]

Injuries from numerous aircraft crashes caused Hughes to spend much of his later life in pain, and he eventually became addicted to codeine, which he injected intramuscularly.[70] He had his hair cut and nails trimmed only once a year, likely due to the pain caused by the RSD/CRPS, which was caused by the plane crashes.[70] He also stored his urine in bottles.[149][150]

Later years in Las Vegas

[edit]The wealthy and aging Hughes, accompanied by his entourage of personal aides, began moving from one hotel to another, always taking up residence in the top floor penthouse. In the last ten years of his life, 1966 to 1976, Hughes lived in hotels in many cities—including Beverly Hills, Boston, Las Vegas, Nassau, Freeport[151] and Vancouver.[152]

On November 24, 1966 (Thanksgiving Day),[153] Hughes arrived in Las Vegas by railroad car and moved into the Desert Inn. Because he refused to leave the hotel and to avoid further conflicts with the owners, Hughes bought the Desert Inn in early 1967. The hotel's eighth floor became the center of Hughes' empire, and the ninth-floor penthouse became his personal residence. Between 1966 and 1968, he bought several other hotel-casinos, including the Castaways, New Frontier, the Landmark Hotel and Casino, and the Sands.[154] He bought the small Silver Slipper casino for the sole purpose of moving its trademark neon silver slipper which was visible from his bedroom, and had apparently kept him awake at night.[citation needed] After Hughes left the Desert Inn, hotel employees discovered that his drapes had not been opened during the time he lived there and had rotted through.[155]

Hughes wanted to change the image of Las Vegas to something more glamorous. He wrote in a memo to an aide, "I like to think of Las Vegas in terms of a well-dressed man in a dinner jacket and a beautifully jeweled and furred female getting out of an expensive car."[156] Hughes bought several local television stations (including KLAS-TV).[157]

Eventually, the brain trauma from Hughes' previous accidents, the effects of neurosyphilis diagnosed in 1932[158] and undiagnosed obsessive-compulsive disorder[159] considerably affected his decision-making. A small panel, unofficially dubbed the "Mormon Mafia" for the many Latter-day Saints on the committee, was led by Frank William Gay and originally served as Hughes' "secret police" headquartered at 7000 Romaine, Hollywood. Over the next two decades, however, this group oversaw and controlled considerable business holdings,[160][161] with the CIA anointing Gay while awarding a contract to the Hughes corporation to acquire sensitive information on a sunken Russian submarine.[162][163] In addition to supervising day-to-day business operations and Hughes' health, they also went to great pains to satisfy Hughes' every whim. For example, Hughes once became fond of Baskin-Robbins's banana nut ice cream, so his aides sought to secure a bulk shipment for him, only to discover that Baskin-Robbins had discontinued the flavor. They put in a request for the smallest amount the company could provide for a special order, 350 gallons (1,300 L), and had it shipped from Los Angeles. A few days after the order arrived, Hughes announced he was tired of banana nut and wanted only French vanilla ice cream. The Desert Inn ended up distributing free banana nut ice cream to casino customers for a year.[164] In a 1996 interview, former Howard Hughes Chief of Nevada Operations Robert Maheu said, "There is a rumor that there is still some banana nut ice cream left in the freezer. It is most likely true."[citation needed]

As an owner of several major Las Vegas businesses, Hughes wielded much political and economic influence in Nevada and elsewhere. During the 1960s and early 1970s, he disapproved of underground nuclear testing at the Nevada Test Site. Hughes was concerned about the risk from residual nuclear radiation and attempted to halt the tests. When the tests finally went through despite Hughes' efforts, the detonations were powerful enough that the entire hotel in which he was living trembled from the shock waves.[165] In two separate, last-ditch maneuvers, Hughes instructed his representatives to offer bribes of $1 million to both Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon.[166]

In 1970, Jean Peters filed for divorce. The two had not lived together for many years. Peters requested a lifetime alimony payment of $70,000 a year, adjusted for inflation, and waived all claims to Hughes' estate. Hughes offered her a settlement of over a million dollars, but she declined it. Hughes did not insist on a confidentiality agreement from Peters as a condition of the divorce. Aides reported that Hughes never spoke ill of her. She refused to discuss her life with Hughes and declined several lucrative offers from publishers and biographers. Peters would state only that she had not seen Hughes for several years before their divorce and had dealt with him only by phone.[citation needed]

Hughes was living in the Intercontinental Hotel near Lake Managua in Nicaragua, seeking privacy and security,[167] when a magnitude 6.5 earthquake damaged Managua in December 1972. As a precaution, Hughes moved to a large tent facing the hotel; after a few days, he moved to the Nicaraguan National Palace and stayed there as a guest of Anastasio Somoza Debayle before leaving for Florida on a private jet the following day.[168] He subsequently moved into the penthouse at the Xanadu Princess Resort on Grand Bahama Island, which he had recently purchased. He lived almost exclusively in the penthouse of the Xanadu Beach Resort & Marina for the last four years of his life.[citation needed] Hughes spent a total of $300 million on his many properties in Las Vegas.[153]

Autobiography hoax

[edit]In 1972, author Clifford Irving caused a media sensation when he claimed he had co-written an authorized Hughes autobiography. Irving claimed he and Hughes had corresponded through the United States mail and offered as proof handwritten notes allegedly sent by Hughes. Publisher McGraw-Hill, Inc. was duped into believing the manuscript was authentic. Hughes was so reclusive that he did not immediately publicly refute Irving's statement, leading many to believe that Irving's book was genuine. However, before the book's publication, Hughes finally denounced Irving in a teleconference attended by reporters Hughes knew personally: James Bacon of the Hearst papers, Marvin Miles of the Los Angeles Times, Vernon Scott of UPI, Roy Neal of NBC News, Gene Handsaker of AP, Wayne Thomas of the Chicago Tribune, and Gladwin Hill of the New York Times.[169]

The entire hoax finally unraveled.[170] The United States Postal Inspection Service (USPIS) got a subpoena to force Irving to turn over samples of his handwriting. The USPIS investigation led to Irving's indictment and subsequent conviction for using the postal service to commit fraud. He was incarcerated for 17 months.[171] In 1974, the Orson Welles film F for Fake included a section on the Hughes autobiography hoax, leaving a question open as to whether it was actually Hughes who took part in the teleconference (since so few people had actually heard or seen him in recent years). In 1977, The Hoax by Clifford Irving was published in the United Kingdom, telling his story of these events. The 2006 film The Hoax, starring Richard Gere, is also based on these events.[172]

Death

[edit]

Hughes is reported to have died on April 5, 1976, at 1:27 p.m. on board an aircraft, Learjet 24B N855W, owned by Robert Graf and piloted by Roger Sutton and Jeff Abrams.[173] He was en route from his penthouse at the Acapulco Princess Hotel (now the Princess Mundo Imperial) in Mexico to the Methodist Hospital in Houston.[174]

His reclusiveness and possibly his drug use made him practically unrecognizable. His hair, beard, fingernails, and toenails were long—his tall 6 ft 4 in (193 cm) frame now weighed barely 90 pounds (41 kg), and the FBI had to use fingerprints to conclusively identify the body.[175] Howard Hughes' alias, John T. Conover, was used when his body arrived at a morgue in Houston on the day of his death.[176]

An autopsy recorded kidney failure as the cause of death.[177] In an eighteen-month study investigating Hughes' drug abuse for the estate, it was found that "someone administered a deadly injection of the painkiller to this comatose man ... obviously needlessly and almost certainly fatal".[178] He suffered from malnutrition and was covered in bedsores. While his kidneys were damaged, his other internal organs, including his brain, which had no visible damage or illnesses, were deemed perfectly healthy.[70] X-rays revealed five broken-off hypodermic needles in the flesh of his arms.[70] To inject codeine into his muscles, Hughes had used glass syringes with metal needles that easily became detached.[70]

Hughes is buried next to his parents at Glenwood Cemetery in Houston.[179]

Alleged survival

[edit]Following his death, Hughes was subject to several widely rebuked conspiracy theories that he had faked his own death. A notable allegation came from retired Major General Mark Musick, Assistant Secretary of the Air Force, who claimed Hughes went on to live under an assumed identity, dying on November 15, 2001, in Troy, Alabama.[180][181]

Estate

[edit]Approximately three weeks after Hughes' death, a handwritten will was found on the desk of an official of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah. The so-called "Mormon Will" gave $1.56 billion to various charitable organizations (including $625 million to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute), nearly $470 million to the upper management in Hughes' companies and to his aides, $156 million to first cousin William Lummis, and $156 million split equally between his two ex-wives Ella Rice and Jean Peters.

A further $156 million was endowed to a gas station owner, Melvin Dummar, who told reporters that in 1967, he found a disheveled and dirty man lying along U.S. Route 95, just 150 miles (240 km) north of Las Vegas. The man asked for a ride to Vegas. Dropping him off at the Sands Hotel, Dummar said the man told him that he was Hughes. Dummar later claimed that days after Hughes' death a "mysterious man" appeared at his gas station, leaving an envelope containing the will on his desk. Unsure if the will was genuine and unsure of what to do, Dummar left the will at the LDS Church office. In 1978, a Nevada court ruled the Mormon Will a forgery and officially declared that Hughes had died intestate (without a valid will). Dummar's story was later adapted into Jonathan Demme's film Melvin and Howard in 1980.[182]

Hughes' $2.5 billion estate was eventually split in 1983 among 22 cousins, including William Lummis, who serves as a trustee of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The Supreme Court of the United States ruled that Hughes Aircraft was owned by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which sold it to General Motors in 1985 for $5.2 billion. The court rejected suits by the states of California and Texas that claimed they were owed inheritance tax.

In 1984, Hughes' estate paid an undisclosed amount to Terry Moore, who claimed she and Hughes had secretly married on a yacht in international waters off Mexico in 1949 and never divorced. Moore never produced proof of a marriage, but her book, The Beauty and the Billionaire, became a bestseller.

Awards

[edit]- Harmon Trophy (1936 and 1938)

- Collier Trophy (1938)

- Congressional Gold Medal (1939)

- Octave Chanute Award (1940)

- National Aviation Hall of Fame (1973)

- International Air & Space Hall of Fame (1987)[183]

- Motorsports Hall of Fame of America (2018)[184]

Archive

[edit]The moving image collection of Howard Hughes is held at the Academy Film Archive. The collection consists of over 200 items including 35mm and 16mm elements of feature films, documentaries, and television programs made or accumulated by Hughes.[185]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Director | Producer | Writer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | Two Arabian Knights | No | Yes | No |

| 1930 | Hell's Angels | Yes | Yes | No |

| 1931 | The Front Page | No | Yes | No |

| 1932 | Sky Devils | No | Yes | No |

| Scarface | No | Yes | No | |

| 1943 | The Outlaw | Yes | Yes | No |

| Behind the Rising Sun | No | Yes | No | |

| 1947 | The Sin of Harold Diddlebock | No | Uncredited | No |

| 1950 | Vendetta | No | Yes | No |

| 1951 | His Kind of Woman | No | Executive | Uncredited |

| 1952 | Macao | No | Yes | No |

| 1955 | Son of Sinbad | No | Executive | No |

| 1955 | Underwater! | No | Yes | No |

| 1956 | The Conqueror | No | Yes | No |

| 1957 | Jet Pilot | No | Yes | No |

In popular culture

[edit]Film

[edit]- In The Carpetbaggers (1964), the main character Jonas Cord (played by George Peppard) is loosely based on Howard Hughes.

- The James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever (1971) features a tall, Texan, reclusive billionaire character named Willard Whyte (played by Jimmy Dean) who operates his business empire from the penthouse of a Las Vegas hotel. Although he appears only late in the film, his habitual seclusion and his control of a major aerospace contracting firm are key elements of the film's plot. Several sequences were actually filmed on location at The Landmark Hotel and Casino, which was owned by Hughes at the time.

- The Amazing Howard Hughes is a 1977 American made-for-television biographical film which aired as a mini-series on the CBS network, made a year after Hughes' death and based on Noah Dietrich's book Howard: The Amazing Mr. Hughes. Tommy Lee Jones plays Hughes.

- Melvin and Howard (1980), directed by Jonathan Demme and starring Jason Robards as Howard Hughes and Paul Le Mat as Melvin Dummar. The film won Academy Awards for Best Original Screenplay (Bo Goldman) and Best Supporting Actress (Mary Steenburgen). The film focuses on Melvin Dummar's claims of meeting Hughes in the Nevada desert and subsequent estate battles over his inclusion in Hughes' will. Critic Pauline Kael called the film "an almost flawless act of sympathetic imagination".[186]

- The film Creepshow from 1982 has a segment titled "They're Creeping Up on You!". The reclusive, paranoid, tycoon Upson Pratt, played by E. G. Marshall appears to be loosely based upon Hughes. [original research?]

- In Tucker: The Man and His Dream, (1988), Hughes (played by Dean Stockwell) figures in the plot by telling Preston Tucker to source steel and engines for Tucker's automobiles from a helicopter manufacturer in New York. Scene occurs in a hangar with the Hercules.

- In The Rocketeer, a 1991 American period superhero film from Walt Disney Pictures, the title character attracts the attention of Howard Hughes (played by Terry O'Quinn) and the FBI, who are hunting for a missing jet pack, as well as Nazi operatives.

- "Howard Hughes Documentary", broadcast in 1992 as an episode of the Time Machine documentary series, was introduced by Peter Graves, later released by A&E Home Video.[187]

- In Conspiracy Theory (1997), the character Jerry Fletcher (played by Mel Gibson) mentions one of his theories to a street vendor by saying, "Did you know that the whole Vietnam War was fought over a bet that Howard Hughes lost to Aristotle Onassis?" referring to his (Fletcher's) thoughts on the politics of that conflict.

- In The Aviator (2004), directed by Martin Scorsese, Hughes is portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio. The film focuses on Hughes' personal life from the making of Hell's Angels through his successful flight of the Hercules or Spruce Goose. Critically acclaimed, it was nominated for 11 Academy Awards, winning five for Best Cinematography; Best Film Editing; Best Costume Design; Best Art Direction; and Best Actress in a Supporting Role for Cate Blanchett.

- Howard Hughes: The Real Aviator documentary was broadcast in 2004 and went on to win the Grand Festival Award for Best Documentary at the 2004 Berkeley Video & Film Festival.[188]

- In the 2005 animated film Robots, the character Mr Bigweld (voiced by Mel Brooks), a reclusive inventor and owner of Bigweld Industries, is loosely based on Howard Hughes.

- The American Aviator: The Howard Hughes Story was broadcast in 2006 on the Biography Channel. It was later released to home media as a DVD with a copy of the full-length film The Outlaw starring Jane Russell.[189]

- Captain America: The First Avenger (2011), the character Howard Stark (played by Dominic Cooper), a wealthy inventor of futuristic technology, clearly embodying Hughes' persona and enthusiasm. His subsequent appearances in the TV series Agent Carter further this persona, as well as depicting him as sharing the real Hughes' reputation as a womanizer. Stan Lee has noted that Howard's son Tony Stark (Iron Man), who shared several of these traits himself, was based on Hughes.[190]

- Rules Don't Apply (2016), written and directed by Warren Beatty, features Beatty as Hughes from 1958 through 1964.

- In the Dark Knight Trilogy, director Christopher Nolan's characterization of Bruce Wayne is heavily inspired by Hughes' perceived lifestyle – from a playboy in Batman Begins to a recluse in The Dark Knight Rises. Nolan is reported to have integrated his original material intended for a shelved Hughes biopic into the trilogy.[191]

- In The Hoax (2006) - in what would cause a fantastic media frenzy - Clifford Irving sells his bogus biography of Howard Hughes to a premiere publishing house in the early 1970s.[192]

Games

[edit]- The character of Andrew Ryan in the 2007 video game BioShock is loosely based on Hughes. Ryan is a billionaire industrialist in post-World War II America who, seeking to avoid governments, religions, and other "parasitic" influences, ordered the secret construction of an underwater city, Rapture. Years later, when Ryan's vision for Rapture falls into dystopia, he hides himself away and uses armies of mutated humans, "Splicers", to defend himself and fight against those trying to take over his city, including the player-character.[193]

- In L.A. Noire, Hughes makes an appearance presenting his Hercules H-4 aircraft in the game opening scene. The H-4 is later a central plot piece of DLC Arson Case, "Nicholson Electroplating".[194]

- In Fallout: New Vegas, the character of Robert Edwin House, a wealthy business magnate and entrepreneur who owns the New Vegas strip, is based on Howard Hughes and closely resembles him in appearance, personality and background. A portrait of Mr. House can also be found in the game which strongly resembles a portrait of Howard Hughes standing in front of a Boeing Army Pursuit Plane.[195]

Literature

[edit]- Stan Lee repeatedly stated he created the Marvel Comics character Iron Man's civilian persona, Tony Stark, drawing inspiration from Howard Hughes' colorful lifestyle and personality. Additionally, the first name of Stark's father is Howard.[196]

- Hughes is a supporting character in all three parts of James Ellroy's Underworld USA Trilogy, employing several of the protagonists as private investigators, bagmen, and consultants in his attempt to assume control of Las Vegas. Referred to behind his back as "Count Dracula" (due to his reclusiveness and rumored obsession with blood transfusions from Mormon donors), Hughes is portrayed as a spoiled, racist, opioid-addicted megalomaniac whose grandiose plans for Las Vegas are undermined by the manipulations of the Chicago Outfit.

- In the 1981 novel Dream Park by Larry Niven and Steven Barnes, the weapon "which might have defeated the Japs if it hadn't come so late" is revealed to be the Spruce Goose, which had been magically hijacked on its test flight by evil Foré sorcerers in New Guinea. Hughes' skeleton is found at the controls, identified by Hughes' trademark fedora and cloth-and-leather jacket.

Music

[edit]- The 1973 song "Broadway melody of 1974" by Genesis referenced Howard Hughes: "There's Howard Hughes in blue suede shoes / Smiling at the majorettes, smoking Winston cigarettes".[197]

- The 1974 song "Workin' at the Car Wash Blues" by Jim Croce compares the main protagonist of the song to Howard Hughes in one of the lyrics.

- The 1974 song "The Wall Street Shuffle" by English rock band 10cc directly references Hughes and his ways of life in the last verse.

- The name of the musical group The Hues Corporation who had the 1974 hit song "Rock the Boat" was selected since it was a heterophonic spelling of Hughes as in Howard Hughes.

- The song "Me and Howard Hughes" by Irish band The Boomtown Rats on their 1978 album A Tonic for the Troops is about the title subject.

- The song "Closet Chronicles" by American rock band Kansas on their 1977 album Point of Know Return is a Howard Hughes allegory.

- The song "Ain't No Fun (Waiting 'Round To Be a Millionaire)" by AC/DC on their 1976 album "Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap" singer Bon Scott referenced Howard Hughes toward the end of the song: "Hey, hello Howard, how you doin', my next door neighbour? Oh, yea... Get your fuckin' jumbo jet off my airport"

- The 1983 song "Casanova Brown" by Teena Marie includes the lyric "He's had more girls than Howard Hughes had money".

- Hughes' name is mentioned in the title and the lyrics of the 2002 song "Bargain Basement Howard Hughes" by Jerry Cantrell.

- The 2008 song "Howard" by American pop-punk band Bayside is written about Hughes.

- The 2012 song "Nancy From Now On" by American songwriter Father John Misty likens Hughes' destructive and erratic tendencies to the singer's own.[198]

- The 1996 album "Thanks for the Ether" by Rasputina features a song titled "Howard Hughes" about Hughes' eccentricities and isolation in his later life.

Television

[edit]- In Episode 14 of Lupin III Part 2, the owner of a cursed ruby is named Howard Heath. Heath is based on Hughes, who had only recently died when the episode aired.

- In the 1973 episode of the Partridge Family, John Astin plays a reclusive millionaire in "Diary of a Mad Millionaire"[199] who was readily recognized as a reference to Howard Hughes who was famous for being a recluse at that time.

- In The Greatest American Hero Season 2 episode 3, "Don't Mess Around with Jim", Ralph and Bill are kidnapped by a reclusive tycoon, owner of Beck Air airplane company, who fakes his own death, and seems to know more about the suit than they do. He then blackmails them into retrieving his will to prevent it from being misused by the president of his company.

- In Benson Season 6, Episode 2, "The Inheritance," Benson learns he has inherited the assets of Hugh Howard, a pastiche of Howard Hughes and Hugh Hefner, including his Playboy-like magazine, which becomes embarrassing for him, the Governor, and the Governor's staff.

- In The Simpsons Season 5 episode "$pringfield (Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Legalized Gambling)", Mr. Burns resembles Hughes in his recluse state. Various nods to his life appear in the episode, ranging from casino ownership and penthouse office to the "Spruce Goose" being renamed "Spruce Moose" as well as a lack of hygiene and being a germaphobe.

- In The Beverly Hillbillies episode, "The Clampett-Hewes Empire", Jed Clampett, while in Hooterville, decides to merge his interests with a man Mr. Drysdale believes is Howard Hughes, the famous reclusive billionaire. Eventually it turns out, to Mr. Drysdale's chagrin, "Howard Hughes" is no billionaire; he is, in fact, nothing but a plain old farmer and severely henpecked husband with the homophonic name "Howard Hewes" (H-E-W-E-S).

- In the Invader Zim episode, "Germs", the alien Zim becomes paranoid after discovering that Earth is covered in germs. Referencing Howard Hughes, he isolates himself in his home and dons tissue boxes on his feet.

- In the Superjail! episode "The Superjail! Six", The Warden repeatedly watches a film called Ice Station Jailpup which parodies Hughes' obsession with the film Ice Station Zebra

- In the Phineas and Ferb episode "De Plane! De Plane!" , Phineas and Ferb are watching an informational TV show, where it tells about Howard Hughes' Spruce Goose, which is the largest plane ever built. Phineas and Ferb set out to build a bigger plane than the wooden Spruce Goose.

- In the Dark Skies episode Dreamland, John and Kim travel to Las Vegas where they are tasked by Howard Hughes to investigate a possible Hive infiltration of Area 51. Hughes is portrayed as extremely mysophobic and his encounter at the end of the episode with a Hive (extra-terrestrial) ganglion is presented as the reason for his final seclusion and mental decline.

See also

[edit]- Analgesic nephropathy

- Elon Musk – 21st century businessman that drew comparisons with Howard Hughes

- List of richest Americans in history

- List of aviation pioneers

- List of entrepreneurs

- Phenacetin

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ No time of birth is listed. Record nr. 234358, of December 29, 1941, filed January 5, 1942, Bureau of Vital Statistics of Texas Department of Health.

- ^ The handwriting of the baptismal record is a rather trembling one. The clerk was an aged person and there is a chance that, supposedly being hard of hearing, they misheard "December 24" as "September 24" instead. This is speculative.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Simkin, John. "Howard Hughes".Archived June 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Spartacus Educational. Retrieved: June 9, 2013.

- ^ "Howard R. Hughes". UNLV Howard R. Hughes College of Engineering. July 20, 2011. Retrieved July 18, 2018.

- ^ "The Racket (1928)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ "Hell's Angels". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ a b Rumerman, Judy. "Hughes Aircraft." centennialofflight.net, 2003. Retrieved: August 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Dietrich, Noah; Thomas, Bob (1972). Howard, The Amazing Mr. Hughes. Greenwich: Fawcett Publications, Inc. pp. 34, 69.

- ^ "51 Heroes of Aviation." Archived July 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Flying Magazine. Retrieved: December 27, 2014.

- ^ "Howard Hughes, Our Company, History". Howard Hughes Company Website. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ Barlett and Steele 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Barlett, Donald L. and Steele, James B. Howard Hughes: His Life and Madness Norton, 2011, page 29.