House of Hohenzollern: Difference between revisions

→Counts of Zollern (before 1061-1204): ch hyphen to en dash |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

|surname = House of Hohenzollern |

|surname = House of Hohenzollern |

||

|estate = Germany, Prussia, Romania |

|estate = Germany, Prussia, Romania |

||

|coat of arms = [[Image: |

|coat of arms = [[Image:hermann goering]] |

||

|country = [[Germany]], [[Romania]] |

|country = [[Germany]], [[Romania]] |

||

|parent house = |

|parent house = |

||

Revision as of 06:51, 14 September 2012

| House of Hohenzollern | |

|---|---|

| File:Hermann goering | |

| Country | Germany, Romania |

| Founded | 1100s (decade) |

| Founder | Burgrave Frederick I of Nuremberg |

| Current head | Germany and Prussia: HI&RH Prince Georg Friedrich (1994–) Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen: HM King Michael (1947–) |

| Final ruler | Germany and Prussia: Emperor William II (1888–1918) Romania: King Michael (1927–1930, 1940–1947) |

| Titles | Count of Zollern Margrave of Brandenburg Duke of Prussia Burgrave of Nuremberg Margrave of Bayreuth Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach King of Prussia German Emperor Prince of Neuchâtel King of Romania |

| Estate(s) | Germany, Prussia, Romania |

| Deposition | Germany and Prussia: 1918: German Revolution Romania: 1947: Stalinist take-over |

| Cadet branches | Hohenzollern-Hechingen (extinct) Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen Hohenzollern-Haigerloch (extinct) Romania |

The House of Hohenzollern is a noble family and royal dynasty of electors, kings and emperors of Prussia, Germany and Romania. It originated in the area around the town of Hechingen in Swabia during the 11th century. They took their name from their ancestral home, the Burg Hohenzollern castle near Hechingen.

The family uses the motto Nihil Sine Deo (Template:Lang-en). The family coat of arms, first adopted in 1192, began as a simple shield quarterly sable and argent. A century later, in 1317, Frederick IV, Burgrave of Nuremberg, added the head and shoulders of a hound as a crest.[1] Later quartering reflected heiresses’ marriages into the family.

The family split into two branches, the Catholic Swabian branch and the Protestant Franconian branch, known also as the Kirschner line. The Swabian branch ruled the area of Hechingen until their eventual extinction in 1869. The Franconian-Kirschner branch was more successful: members of the Franconian branch became Margrave of Brandenburg in 1415 and Duke of Prussia in 1525. Following the union of these two Franconian lines in 1618, the Kingdom of Prussia was created in 1701, eventually leading to the unification of Germany and the creation of the German Empire in 1871.

Social unrest at the end of World War I led to the German Revolution of 1918, with the formation of the Weimar Republic forcing the Hohenzollerns to abdicate, thus bringing an end to the modern German monarchy. The Treaty of Versailles in 1919 set the final terms for the dismantling of the German Empire.[citation needed].

Origins

Counts of Zollern (before 1061–1204)

The oldest known mention of the Zollern was in 1061. It was a county, ruled by the counts of Zollern, who are believed to have originated from the Burchardinger dynasty.

- until 1061: Burkhard I

- before 1125: Frederick I

- c. 1142 : Frederick II

- before 1171 – c. 1200: Frederick III/I (son of, also Burgrave of Nuremberg)

Count Frederick III of Zollern was a loyal retainer of the Holy Roman Emperors Frederick Barbarossa and Henry VI, and around 1185 he married Sophia of Raabs, the daughter of Conrad II, Burgrave of Nuremberg.

After the death of Conrad II, often referred to as Kurt II who left no male heirs, Frederick III was granted the burgraviate of Nuremberg in 1192 as Burgrave Frederick I of Nuremberg-Zollern. Since then the family name has been Hohenzollern.

After Frederick's death, his sons partitioned the family lands between themselves:

- The older brother,[2] Frederick IV, received the county of Zollern and burgraviate of Nuremberg in 1200 from his father, thereby founding the Swabian branch of the House of Hohenzollerns. The Swabian line remained Catholic.

- The younger brother,[2] Conrad III, received the burgraviate of Nuremberg from his older brother Frederick IV in 1218, thereby founding the Franconian branch of the House of Hohenzollern. The Franconian line later converted to Protestantism.

Franconian cadet branch and Brandenburg-Prussian Branch

The cadet Franconian branch of the House of Hohenzollern was founded by Conrad III, Burgrave of Nuremberg.

Beginning in the 16th century, this branch of the family became Protestant and decided on expansion through marriage and the purchase of surrounding lands.

The family supported the Hohenstaufen and Habsburg rulers of the Holy Roman Empire during the 12th to 15th centuries, and they were rewarded with several territorial grants.

In the first phase, the family gradually added to their lands, at first with many small acquisitions in the Franconian and Bavarian regions of Germany:

In the second phase, the family expanded their lands further with large acquisitions in the Brandenburg and Prussian regions of Germany and Poland:

- Margraviate of Brandenburg in 1417

- Duchy of Prussia in 1618

These acquisitions eventually transformed the Hohenzollerns from a minor German princely family into one of the most important in Europe.

Burgraves of Nuremberg (1192–1427)

- 1192–1200/1204: Frederick I (also count of Zollern as Frederick III)

- 1204–1218: Frederick II (son of, also count of Zollern as Frederick IV)

- 1218–1261/1262: Conrad I/III (brother of, also count of Zollern)

- 1262–1297: Frederick III (son of)

- 1297–1300: John I (son of)

- 1300–1332: Frederick IV (brother of)

- 1332–1357: John II (son of)

- 1357–1398: Frederick V (son of)

At Frederick V's death on 21 January 1398, his lands were partitioned between his two sons:

- 1398–1420: John III/I (son of, also Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach)

- 1420–1427: Frederick VI/I/I, (brother of, also Elector of Brandenburg and Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach)

After John III/I's death on 11 June 1420, the two principalities were briefly reunited under Frederick VI/I/I. From 1412 Frederick VI became Margrave of Brandenburg as Frederick I and Elector of Brandenburg as Frederick I. From 1420, he became Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach. Upon his death on 21 September 1440, his territories were divided between his sons:

- John II, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach

- Frederick II, Elector of Brandenburg

- Albert III, Elector of Brandenburg and Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach

From 1427 onwards the title of Burgrave of Nuremberg was absorbed into the titles of Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach and Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach.

Margraves of Brandenburg-Ansbach (1398–1791)

- 1398: Frederick I (also Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach)

- 1440: Albert I/I/III Achilles (son of, also Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach and Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1486: Frederick II/II (son of, also Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach)

- 1515: George I/I the Pious (son of, also Duke of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf)

- 1543: George Frederick I/I/I/I (son of, also Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach, Duke of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf and Regent of Prussia)

- 1603: Joachim Ernst

- 1625: Frederick III

- 1634: Albert II

- 1667: John Frederick

- 1686: Christian I Albrecht

- 1692: George Frederick II/II (later Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach)

- 1703: William Frederick (before 1686–1723)

- 1723: Charles William (1712–1757)

- 1757: Christian II Frederick (1757–1791) (son of, also Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach)

On 2 December 1791, Christian II Frederick sold the sovereignty of his principalities to king Frederick William II of Prussia.

Margraves of Brandenburg-Kulmbach (1398-1604), later Brandenburg-Bayreuth (1604–1791)

- 1397: John I

- 1420: Frederick I (also Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach)

- 1440: John II

- 1457: Albert I/I/III Achilles (also Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach and Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1486: Siegmund

- 1495: Frederick II/II (also Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach)

- 1515: Casimir

- 1527: Albert II Alcibiades

- 1553: George Frederick I/I/I/I (also Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Duke of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf and Regent of Prussia)

- 1603: Christian I

- 1655: Christian II Ernst

- 1712: George I William

- 1726: George Frederick II/II (previously Margrave of Kulmbach)

- 1735: Frederick IV

- 1763: Frederick V Christian

- 1769: Christian II Frederick (until 1791, also Margrave of brandenburg-Ansbach)

On 2 December 1791, Christian II Frederick sold the sovereignty of his principalities to king Frederick William II of Prussia.

Prussia)

From 1701 the title of Elector of Brandenburg was attached to the title of King in and of Prussia.

Dukes of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf (1523–1622)

The Duchy of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf was purchased in 1523.

- 1541–1543 : George I/I the Pious (also Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach)

- 1543–1603 : George Frederick I/I/I/I (also Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach and Regent of Prussia)

- 1603–1606 : Joachim I/I/III (also Regent of Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1606–1621 : Johann Georg of Hohenzollern

The duchy of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf was confiscated by Ferdinand III of the Holy Roman Empire in 1622.

Margraves of Brandenburg-Küstrin (1535–1571)

The short-lived Margraviate of Brandenburg-Küstrin was set up, against the Hohenzollern house laws on succession, as a secundogeniture fief of the House of Hohenzollern, a typical German institution.

- 1535–1571: John the Wise, Margrave of Brandenburg-Küstrin (son of Joachim I Nestor, Elector of Brandenburg)

He died without issue. The Margraviate of Brandenburg-Küstrin was absorbed in 1571 into the Margraviate and Electorate of Brandenburg.

Margraves of Brandenburg-Schwedt (1688–1788)

From 1688 onwards the Margraves of Brandenburg-Schwedt were a side branch of the House of Hohenzollern. Though recognised as a branch of the main dynasty the Margraviate of Brandenburg-Schwedt never constituted a principality with allodial rights of its own.

- 1688–1711 : Philip William, Prince in Prussia, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt (son of Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1731–1771 : Frederick William, Prince in Prussia, Margrave of Brandenburg-Schwedt (son of)

- 1771–1788 : Frederick Henry, Prince in Prussia, Margrave of Brandenburg Schwedt (brother of)

In 1788 the title was incorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia.

Dukes of Prussia (1525–1701)

In 1525 the Duchy of Prussia was established as a fief of the King of Poland.

- 1525–1568: Albert I

- 1568–1618: Albert II Frederick co-inheritor (son of)

- 1568–1571: Joachim I/II Hector co-inheritor (also Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1578–1603: George Frederick I/I/I/I (Regent, also Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach and Duke of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf)

- 1603–1608: Joachim I/I/III Frederick (Regent, also Duke of Brandenburg-Jägerndorf and Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1608–1618: John I/III Sigismund (Regent, also Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1618–1619: John I/III Sigismund (Regent, also Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1619–1640: George William I/I (son of, also Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1640–1688: Frederick I/III William the Great Elector (son of, also Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1688–1701: Frederick II/IV/I (also Elector of Brandenburg and King in Prussia)

From 1701 the title of Duke of Prussia was attached to the title of King in and of Prussia.

Kings in Prussia (1701–1772)

In 1701 the title of King in Prussia was granted, without the Duchy of Prussia being elevated to a Kingdom within the Holy Roman Empire. From 1701 onwards the titles of Duke of Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg were always attached to the title of King in Prussia.

- 1701–1713: Frederick I/II/IV (also Duke of Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg)

- 1713–1740: Frederick William I (son of)

- 1740–1786: Frederick II (son of, later also King of Prussia)

In 1772 the Duchy of Prussia was elevated to a kingdom.

Kings of Prussia (1772–1918)

In 1772 the title of King of Prussia was granted with the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia. From 1772 onwards the titles of Duke of Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg were always attached to the title of King of Prussia.

- Frederick II (1740–1786) (son of, before King in Prussia)

- Frederick William II (1786–1797) (nephew of)

- Frederick William III (1797–1840) (son of)

- Frederick William IV (1840–1861) (son of)

- William I (1861–1888) (brother of)

- Frederick III (1888) (son of)

- William II (1888–1918) (son of)

In 1871 the Kingdom of Prussia was a constituting member of the German Empire.

German Kings and Emperors (1871–1918)

Reigning (1871–1918)

In 1871 the German Empire was proclaimed. With the accession of Wilhelm I to the newly-established imperial German throne, the titles of King of Prussia, Duke of Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg were always attached to the title of German Emperor.

- 1871–1888: William I (also King of Prussia)

- 1888: Frederick III (son of, also King of Prussia)

- 1888–1918: William II (grandson of, also King of Prussia)

In 1918 the German empire was abolished and replaced by the Weimar Republic.

Line of succession (1918 to present)

Despite the abolition of the German monarchy in 1918, the House of Hohenzollern never relinquished their claims to the thrones of Prussia and the German Empire. These claims are linked by the Constitution of the second German Empire: according to this, whoever was King of Prussia was also German Emperor. However, these claims are not recognised by the Federal Republic of Germany.

| Name | Titular reign |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

| William II | 1918–1941 | Exiled in the Netherlands until his death |

| Crown Prince William | 1941–1951 | |

| Prince Louis Ferdinand | 1951–1994 | |

| Prince Georg Friedrich | since 1994 | |

| Prince Christian Sigismund | heir presumptive |

The head of the house is the titular King of Prussia and German Emperor. He also bears a historical claim to the title of prince of Orange. Members of this line style themselves princes of Prussia.

Genealogy and Coat of arms of the Hohenzollerns, Brandenburg, Prussia, and the German Empire

An article on the Coat of arms of Prussia can be found. The explanation of the shield can be found at Great Shield of the Kings of Prussia (German).

-

Lesser Arms of the Prince-Elector of Brandenburg in 1686

-

Arms of the Prince-Elector of Brandenburg in 1686

-

Prussian arms of 1702

-

Royal arms after a woodcut from 1709

On 27 January 1701, King Frederick I changed his arms as prince-elector of Brandenburg. The older arms of the electors of Brandenburg depicted a red eagle on a white background. Henceforth, the Prussian eagle, now royally crowned and with 'FR' (Fridericus Rex, "King Frederick") on its breast, was placed in an escutcheon on the shield with 25 quarters instead of the electoral scepter. All the helmets made way for one royal crown.

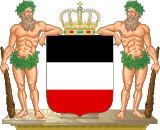

The wild men – figures from Germanic and Celtic mythology representing the 'Lord of the Beasts' or 'Green Man' – that held the arms of Prussia are probably taken from the arms of Pomerania or Denmark. They are also to be found as supporters of the arms of Braunschweig, Königsberg, and the Dutch towns of Anloo, Beilen, Bergen op Zoom, Groede, Havelte, 's-Hertogenbosch, Oosterhesselen, Sleen, Sneek, Vries and Zuidwolde.[3] A wild man and a wild woman have held the shield of the principality of Schwarzburg in Thuringia and the city of Antwerp since the beginning of the 16th century.[4] Two wild men and a wild woman have been included in the seal of Bergen op Zoom since 1365.[5]

A decree from 11 February 1701 placed a crown on the Prussian escutcheon. The king ordained that the whole should be placed on a royal pavilion after the French and Danish examples.

When William III, Prince of Orange and King of England, died on 19 March 1702, the king ordered the arms of the principality placed on his shield. This was to support his claim as heir general, although the Frisian branch of the House of Orange-Nassau claimed it as well.

In 1708 Frederick announced that he would place the quarters of the dukes of Mecklenburg in the Prussian arms to stress his rights to Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Mecklenburg-Strelitz if their ducal lines were to die out. Although Mecklenburg-Strelitz protested, Emperor Joseph I gave permission to Frederick in October 1712. This design was twice officially altered but was not fundamentally changed since.

The electoral scepter had its own shield under the electoral cap. Around the shield, with 36 quarters (including Veere-Vlissingen and Breda), appeared the Order of the Black Eagle with a crowned helmet resting on top. The wild men held banners of Prussia and Brandenburg and behind the pavilion rose a Prussian banner after the example of the French Oriflamme. The motto Gott mit uns ("God with us") appeared on the pedestal.

Already during the reign of Frederick I there is a notable difference between the 'Gothic' representation of the Prussian eagle in the arms and the more naturally depicted and often flying eagle on most coins[6] and military standards.[7]

-

Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Prussia

-

Small arms of 1790

-

"Middle arms" of 1873

-

Greater arms of Prussia, ca. 1873

-

Coat of arms of Prussia 1815

Frederick William I followed his father on the throne on 25 February 1713. According to Ströhl he gave the eagle a scepter and orb. He made an arrangement with the Frisian Nassaus over the title to the Principality of Orange, although it was occupied by France. Besides the arms of Orange, he officially added Veere and Vlissingen on 29 July 1732. The king also added East Frisia to his arms, claiming it in case the prince would die without heir. A fourth escutcheon appeared among the 36 quarters.

Frederick II became king on 31 May 1740. He laid claim to the duchy of Silesia after the death of Emperor Charles VI and declared war on Charles' daughter and heir, Maria Theresa of Austria, thereby starting the Silesian Wars.

Frederick II was followed by his nephew, Frederick William II, on 17 August 1786. Frederick William II inherited the Franconian cadet branches (Ansbach and Bayreuth) of the House of Hohenzollern in 1791. For reasons of economy, however, the official seals were unchanged.

Frederick William III took the throne on 16 November 1797 and changed the arms on 3 July 1804. The reorganisation of Germany by Napoleon I of France made alterations necessary. A new escutcheon was created for Silesia and the shield held 42 quarters. The Order of the Red Eagle of the Franconian line was also added around the shield.

After the fall of Napoleon, Prussia gained extensive territories on the Rhine and in Saxony. New arms were therefore decreed on 9 January 1817. The number of quarters rose to 48, including the horse of Westphalia and Lower Saxony. The number of escutcheons was reduced to four: the black eagle of Prussia, the red eagle of Brandenburg instead of the scepter, the burgraviate of Nuremberg (though ceded to Bavaria), and Hohenzollern proper.

The so-called 'middle arms' were then issued: a shield with the same four escutcheons and ten quarters for Silesia, Rhineland, Posen, Saxony, Pomerania, Magdeburg, Jülich-Cleves-Berg, and Westphalia. This was encircled by the Order of the Black Eagle and held by two wild men with clubs.

The small arms already in use on coins of the 1790s were legitimized as well.

On 7 December 1849, the Swabian lines of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen and Hohenzollern-Hechingen were annexed by Frederick William IV, who had followed his father on 7 July 1840.

Frederick William IV was followed by his brother William I on 2 January 1861. He changed the arms on 11 January 1864 by combining the escutcheons of Nuremberg and Hohenzollern. After the Second Schleswig War of 1864 and the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, Prussia annexed Schleswig, Holstein, Hanover, Hesse-Kassel (or Hesse-Cassel), and Nassau. King William I of Prussia became William I, German Emperor on 18 January 1871 during the unification of Germany. The Kingdom of Prussia became the predominant state in the newly created German Empire.

William decreed new arms on 16 August 1873. The number of quarters was again 48 with three escutcheons. Added were the collars of the Order of the House of Hohenzollern and the Order of the Prussian Crown. The motto was placed on the dome of the pavilion.

The middle arms of 1873 show more clearly the changes by the additions of Schleswig-Holstein, Hanover, and Hesse-Kassel and the removals of Magdeburg and Cleves-Jülich-Berg.[8]

-

Coat of arms of the Kingdom of Prussia (1871–1918), in the era of Wilhelm II

The Hohenzollern family uses the motto Nihil Sine Deo (English: Nothing Without God). The family coat of arms, first adopted in 1192, began as a simple shield quarterly sable and argent. A century later, in 1317, Frederick IV, Burgrave of Nuremberg, added the head and shoulders of a hound as a crest.[9] Later quartering reflected heiresses’ marriages into the family.

Free State of Prussia

With the fall of the House of Hohenzollern in 1918, the Kingdom of Prussia was succeeded by the Free State of Prussia within the Weimar Republic. The new Prussian arms depicted a single black eagle, displayed in a more natural than heraldic style. While part of Nazi Germany, the free state's arms depicted a single black eagle, more stylized than before but not in a heraldic manner, with a swastika and the phrase Gott mit uns beginning in 1933. The Reichsstatthaltergesetz of 1935 removed all effective power from the Prussian government.

-

Arms of the Free State of Prussia while part of the Weimar Republic (1918–33)

-

Arms of the Free State of Prussia after the 1933 Nazi Machtergreifung

| Federal coat of arms of Germany | |

|---|---|

| |

| Versions | |

Version (Bundesschild) used on the German state and military flags | |

| Armiger | Federal Republic of Germany |

| Adopted | 20 January 1950 |

| Shield | Or, an eagle displayed sable armed beaked and langued gules |

The coat of arms of Germany, also known as Bundesrepublik Deutschland displays a black eagle with a red beak, a red tongue and red feet on a golden field, which is blazoned: Or, an eagle displayed sable beaked langued and membered gules. This is the Bundesadler (German for 'Federal Eagle'), formerly known as Reichsadler (German: [ˈʁaɪ̯çsˌʔaːdlɐ] ⓘ, German for 'Imperial Eagle'). It is one of the oldest coats of arms in the world, and today the oldest national symbol used in Europe.

It is a re-introduction of the coat of arms of the Weimar Republic (in use 1919–1935), which was adopted by the Federal Republic of Germany in 1950.[10] The current official design is due to Karl-Tobias Schwab (1887–1967) and was originally introduced in 1928.

The German Empire of 1871–1918 had re-introduced the medieval coat of arms of the Holy Roman Emperors, in use during the 13th and 14th centuries (a black single-headed eagle on a golden background), before the emperors adopted the double-headed eagle, beginning with Sigismund of Luxemburg in 1433. The single-headed Prussian Eagle (on a white background; blazoned: Argent, an eagle displayed sable) was used as an escutcheon to represent the Prussian kings as dynasts of the German Empire. The Weimar Republic introduced a version in which the escutcheon and other monarchical symbols were removed.

The Federal Republic of Germany adopted the Weimar eagle as its symbol in 1950. Since then, it has been known as the Bundesadler ("federal eagle"). The legal basis of the use of this coat of arms is the announcement by President Theodor Heuss, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and Interior Minister Gustav Heinemann of 20 January 1950, which is word for word identical to the announcement by President Friedrich Ebert and Interior Minister Erich Koch-Weser by 11 November 1919:

By reason of a decision of the Federal Government I hereby announce that the Federal coat of arms on a gold-yellow shield shows the one headed black eagle, the head turned to the right, the wings open but with closed feathering, beak, tongue and claws of red color. If the Federal Eagle is shown without a frame, the same charge and colors as those of the eagle of the Federal coat of arms are to be used, but the tops of the feathers are directed outside. The patterns kept by the Federal Ministry of the Interior are definitive for the heraldic design. The artistic design is reserved to each special purpose.

— The Federal President Theodor Heuß, The Federal Chancellor Adenauer, The Federal Minister of the Interior Heinemann, Announcement concerning the federal coat of arms and the federal eagle.[11]

Since the accession (1990) of the states that used to form the German Democratic Republic, the Federal Eagle has been the symbol of the reunified Germany.

Official depictions of the eagle can be found not only in the federal coat of arms but also on the federal institutions flag, the standard of the president of Germany and official seals. These are designs by various artists of the Weimar period and differ primarily in the shape and position of the wings. A large and rather plump version of the eagle decorates the chamber of the Bundestag, the German parliament; it is sometimes called Fette Henne ("Fat Hen"), with a similar representation found on the German euro coins. In addition to the official depictions, artistic renderings of the federal eagle are permitted and have found their way onto coins, stamps and the letterhead of federal authorities. In 1997 the Federal Press Office implemented a slightly simplified version of the original von Weech seal design which has since been used as a corporate design of the Federal government especially for publications and media appearances. It has no official status though as it is not mentioned in any ordinance or shown in the binding patterns of 1952 still in effect.[12]

| Variants employed by institutions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bundestag | Bundesrat | President | Cabinet | Federal Constitutional Court |

Previous versions

Holy Roman Empire

The German Imperial Eagle (Reichsadler) originates from a proto-heraldic emblem believed to have been used by Charlemagne, the first Frankish ruler crowned Holy Roman Emperor by the Pope in 800, and derived ultimately from the Aquila or eagle standard, of the Roman army.

By the 13th century the imperial coat of arms was generally recognized as: Or, an eagle displayed sable beaked and membered gules (a black eagle with wings expanded with red beak and legs on a gold field). During the medieval period the imperial eagle was usually single-headed. A double-headed eagle is attributed as the arms of Frederick II in the Chronica Majora (c. 1250). In 1433 the double-headed eagle was adopted by Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor. Thereafter the double-headed eagle was used as the arms of the German emperor, and hence as the symbol of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. From the 12th century the Emperors also used a personal coat of arms separate from the imperial arms. From the reign of Albert II (reigned 1438–39), the Emperors bore the old Imperial arms with an inescutcheon of pretence of his personal family arms, which appears as the black eagle with an escutcheon on his breast.

- Coats of arms of the Holy Roman Empire

-

Usual depiction of arms of Holy Roman Emperor (c. 1200 – c. 1300)

-

Coat of Arms of the Holy Roman Emperor (c.1300-c.1400)

-

First depiction of the Reichsadler as a double-headed eagle (coat of arms of Otto IV from the Chronica Majora, c. 1250)

-

Coat of arms of the Holy Roman Empire with two putti (1540s manuscript)

-

Imperial coat of arms (Römischer Kayserlicher und Königlicher Mayestät Wappen) from Siebmachers Wappenbuch (1605)

-

Coat of arms from 1804 to 1806 under Francis II

German Confederation

In 1815, a German Confederation (Bund) of 39 loosely united German states was founded on the territory of the former Holy Roman Empire. Until 1848, the confederation did not have a coat of arms of its own. The Federal Diet (Bundestag) meeting at Frankfurt am Main used a seal which carried the emblem of the Austrian Empire, since Austria had taken over the union's leadership. It showed a black, double-headed eagle, which Austria had adopted just before the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.

During the 1848 revolution, a new Reich coat of arms was adopted by the National Assembly that convened in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt. The black double-headed eagle was retained, but without the four symbols of the emperor: the sword, the imperial orb, the sceptre and the crown. The eagle rested on a golden shield; above was a five-pointed golden star. On both sides the shield was flanked by three flags with the colors black-red-gold. The emblem, however, never gained general acceptance.

The coat of arms itself was the result of a decision of the federal assembly:

The federal assembly constitutes the old German imperial eagle with the surrounding scripture "German Confederation" and the colors of the former German imperial coat of arms – black, red, gold – to be the coat of arms and colors of the German Confederation and reserves the right, to make further decision about its use according to the lecture of the committee.

— The Federal Assembly of the German Confederation, Federal decision about coat of arms and colors of the German Confederation of 19 March 1848 [13]

- Coats of arms in the times of the German Confederation

-

Coat of arms of the Austrian Empire, 1804–1867

-

Coat of arms of the German Confederation, 1815–1866

-

Coat of arms of the German Empire, 1848–1849

North German Confederation

In 1867, the North German Confederation was established without Austria and the four southern German states (Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt with only its southern half) and under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia (see Coat of arms of Prussia). A new coat of arms was adopted, which consisted of a shield with the colors black-white-red, flanked by two wild men holding cudgels and standing on a pedestal.

| Coat of arms of the North German Confederation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

German Empire

<onlyinclude>

The Reichsadler had already been introduced at the Proclamation of Versailles, although the first version had been only a provisional one. The design of the eagle was altered at least twice during the German Empire (1871–1918). It shows the imperial eagle, a comparatively realistic black eagle, with the heraldic crown of the German Empire. The eagle has a red beak, tongue and claws, with open wings and feathers. In contrast to its predecessor, the eagle of the German Confederation, it has only one head, looking to the right, symbolising that important parts of the old empire, Austria and Bohemia, were not part of this new empire. Its legal basis was an imperial rescript:

To the Reich Chancellor Prince of Bismarck. Following your report of 27 June of this year I authorise: 1. that public authorities and public servants, appointed by the Emperor according to the requirements of the constitution and the laws of the German Empire, are to be called imperial; 2. that the black, one-headed, rightward-looking eagle with red beak, tongue and claws, without scepter and orb, on the breast shield the Prussian eagle, overlaid with the shield of the House of Hohenzollern, (i.e. with inescutcheon of pretence of Hohenzollern ("quarterly argent and sable")) over the same the crown in the form of the crown of Charlemagne, but with two crossing bows, may be brought into use; 3. that the Imperial standard [Script continues]

— Kaiser Wilhelm, Rescript of August third, 1871, concerning the names of the public authorities and public servants of the German Empire, as well as the declaration of the Imperial coat of arms and the Imperial standard[14]

- The coats of arms of the German Empire (1871–1918)

-

Lesser coat of arms of the German Emperor

-

Coat of arms of the German Emperor with crest: imperial coat of arms of His Majesty, 27 April 1871 – 3 August 1871

-

Greater coat of arms of the German Emperor: imperial coat of arms of His Majesty

-

Middle coat of arms of the German Emperor

-

Provisional coat of arms of the German Empire at the Proclamation of Versailles

-

Small or 'lesser' coat of arms of the German Empire, 1871–1889

-

Small or 'lesser' coat of arms of the German Empire, 1889–1918

Weimar Republic

After the introduction of the republic the coat of arms of Germany was also altered accounting for the political changes. The Weimar Republic (1918–1933), retained the Reichsadler without the symbols of the former Monarchy (Crown, Collar, Breast shield with the Prussian Arms). This left the black eagle with one head, facing to the right, with open wings but closed feathers, with a red beak, tongue and claws and white highlighting.

The republican Reichsadler is based on the Reichsadler introduced by the Paulskirche Constitution of 1849, which was decided by the Germany National Assembly in Frankfurt upon Main, at the peak of the German civic movement demanding parliamentary participation and the unification of the German states. The achievements and signs of this movement had been mostly done away after its downfall and the political reaction in the 1850s. Only the tiny German Principality of Waldeck-Pyrmont upheld the tradition and continued to use the German colours called Schwarz-Rot-Gold in German (English: Black-Red-Or).

These signs had remained symbols of the Paulskirche movement and Weimar Germany wanted to express its view of being also originated in that political movement between 1848 and 1852. The republican coat of arms took up the idea of the German crest established by the Paulskirche movement, using the same charge animal, an eagle, in the same colors (black, red and or), but modernising its form, including a reduction of the heads from two to one. The artistic rendition of the eagle was very realistic. This eagle is mounted on a yellow (golden) shield. The coat of arms was announced in 1919 by the President Friedrich Ebert and Interior Minister Erich Koch-Weser:

By reason of a decision of the Reich's Government I hereby announce, that the Imperial coat of arms on a gold-yellow shield shows the one headed black eagle, the head turned to the right, the wings open but with closed feathering, beak, tongue and claws in red colour. If the Reich's Eagle is shown without a frame, the same charge and colors as those of the eagle of the Reich's coat of arms are to be used, but the tops of the feathers are directed outside. The patterns kept by the Federal Ministry of the Interior are decisive for the heraldic design. The artistic design may be varied for each special purpose.

— President Ebert; Minister of the Interior, Koch, Announcement concerning the federal coat of arms and the imperial eagle of 11 November 1919[15]

However, in 1928 the Reichswappen (Reich's coat of arms) designed by Tobias Schwab (1887–1967) in 1926 (or 1924[note 1]) for the German Olympic team became the official emblem.[16][17][18] The Reichswehr adopted the new Reichswappen already in 1927.[18] Emil Doepler's earlier design then became the Reichsschild (Reich's escutcheon) with restricted use such as pennant for government vehicles. In 1920, Sigmund von Weech designed a Staatssiegel (State seal), of which the smaller version was used since 1921 by all Reich ministries and authorities on official documents as a consistent sign. It also appeared on the German passports. In 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany adopted all signs of Weimar Republic, Reichswappen, Reichsschild, Staatssiegel, Reichsflagge as Bundeswappen, Bundesschild. Bundessiegel and Bundesflagge in the 1950s.[18]

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany used the Weimar coat of arms until 1935. The Nazi Party used a stylised black eagle above an oak wreath, with a swastika at its centre. With the eagle looking over its left shoulder, that is, looking to the right from the viewer's point of view, it symbolises the Nazi Party, and was therefore called the Parteiadler. After 1935 the Nazis introduced their party symbol as the national insignia (Hoheitszeichen) as well. This version symbolises the country (Reich) and was therefore called the Reichsadler. It can be distinguished from the Parteiadler because the eagle of the latter is looking over its right shoulder, that is, looking to the left from the viewer's point of view. The emblem was established by a regulation made by the Fuhrer and Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler, 5 November 1935:

To express the unity of party and state in relation to their emblems too, I decide:

Article 1 The Reich holds as emblem of its nationality the national emblem of the National Socialist German Workers Party.

Article 2 The national emblems of the Wehrmacht remain intact.

Article 3 The announcement concerning the imperial coat of arms and the imperial eagle (Reichsgesetzbl. Pg 1877) is cancelled.

Article 4 In agreement with the Representative of the Führer, the Reich Minister of the Interior will enact the regulations necessary to implement Article 1.— The Führer and Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler (and others), Regulation concerning the national emblem of the reich of 5 November 1935[19]

Hitler added on 7 March 1936 that:

In relation to the Regulation concerning the national emblem of the Reich of 5 November 1935, Article 1, I decide: The national emblem of the Reich shows the swastika surrounded by an oak wreath, on the oak wreath an eagle with spread wings. The head of the eagle is turned to the right. For the heraldic design of the national emblem, the included patterns are decisive. The artistic design is varied for each special purpose.

— The Führer and Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler (and others), Regulation concerning the design of the national emblem of the Reich of 7 March 1936[20]

| Insignia of Nazi Germany (1933–45) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Coat of arms of the German Reich (Reichswappen), 1933–35 | Emblem of the German Reich (Reichsadler), 1935–45 | Emblem of the NSDAP (Parteiadler) | Variant emblem of the NSDAP (Parteiadler) | Variant emblem of the German Reich for a German Army (Heer) helmet |

German Democratic Republic

East Germany (German Democratic Republic) used a socialist insignia from 1950 until its reunification with West Germany in 1990. In 1959 the insignia was also added to the flag of East Germany.

| Insignia of the German Democratic Republic | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Emblem of East Germany, 1950–53 | Emblem of East Germany, 1953–55 | Emblem of East Germany, 1955–90 |

See also

- Armorial of Germany

- Coat of arms of Austria

- Coat of arms of Prussia

- Coats of arms of German colonies

- Coats of arms of the Holy Roman Empire

- Origin of the coats of arms of German federal states

Notes

- ^ According to sources of the Germany national football team Schwab created the emblem for the team in 1924.

References

- ^ "A Royal Student Stein". Steincollectors.org. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ a b Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe, Jiří Louda & Michael Maclagan, 1981, pp. 178-179.

- ^ K.L. Sierksma, De gemeentewapens van Nederland, Het Spectrum, Utrecht/Antwerp, 1960

- ^ Hubert de Vries, Wapens van de Nederlanden, Uitg. Jan Mets, Amsterdam, 1995

- ^ W.A. van Ham, Wapens en vlaggen van Noord-Brabant, Walburg Pers, Zutphen, 1986

- ^ Gerhard Schön, Deutscher Münzkatalog. 18. Jahrhundert, Battenberg Verlag, Munich, 1984

- ^ Terence Wise, Military Flags of the World, Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset, 1977

- ^ Siebmacher, Großes Wappenbuch, Band 1, 1. Abteilung, 1. Teil, Nuremberg 1856 and 4. Teil, Nuremberg 1921

- ^ "A Royal Student Stein". Steincollectors.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ Bekanntmachung betreffend das Bundeswappen und den Bundesadler (Proclamation on the Federal Coat-of-Arms and the Federal Eagle), published 20 January 1950, in the Bundesgesetzblatt I 1950, p. 26, and Bekanntmachung über die farbige Darstellung des Bundeswappens (Proclamation on the Coloured Representation of the Federal Coat-of-Arms), published 4 July 1952 in the Bundesanzeiger № 169, 2 September 1952.

- ^ Heuss, Theodor; Adenauer, Konrad; Heinemann, Gustav (20 January 1950), Bekanntmachung betreffend das Bundeswappen und den Bundesadler [Announcement concerning the federal coat of arms and the federal eagle], Bonn

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Walter J. Schütz: Die Republik und ihr Adler. Staatliche Formgebung von Weimar bis heute, in: Christian Welzbacher (ed.): Der Reichskunstwart. Kulturpolitik und Staatsinszenierung in der Weimarer Republik 1918–1933, Weimar 2010, pp. 116–135, here pp. 133–134.

- ^ the German Confederation, The Federal Assembly of (9 March 1948). Bundesbeschluß über Wappen und Farben des Deutschen Bundes vom 9. März 1848. Federal decision about coat of arms and colors of the confederation of German states of 9 March 1848. Frankfurt.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ von Hohenzollern, Wilhelm (The German Emperor and King of Prussia) (1919-11-11). Allerhöchster Erlass vom 3. August 1871, betreffend die Bezeichnung der Behörden und Beamten des Deutschen Reichs, sowie die Feststellung des Kaiserlichen Wappens und der Kaiserlichen Standarte (Rescript of August 3rd, 1871, concerning the names of the public authorities and public servants of the German Empire, as well as the declaration of the Imperial coat of arms and the Imperial standard). Berlin. pp. Reichsgesetzblatt 1871. Nr. 681 Pg. 318 and 458.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ebert, Friedrich; Koch-Weser, Erich (11 November 1919). Bekanntmachung betreffend das Reichswappen und den Reichsadler (Announcement concerning the imperial coat of arms and the imperial eagle). Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cf. Reichswappen as depicted in the table: "Deutsches Reich: Wappen I" in: Der Große Brockhaus: Handbuch des Wissens in zwanzig Bänden: 21 vols., Leipzig: Brockhaus, 151928–1935; vol. 4 "Chi–Dob" (1929), p. 648.

- ^ Jürgen Hartmann, "Der Bundesadler", in: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (No. 03/2008), Institut für Zeitgeschichte (ed.), pp. 495–509, here p. 501.

- ^ a b c Jana Leichsenring, "Staatssymbole: Der Bundesadler", in: Aktueller Begriff, Deutscher Bundestag – Wissenschaftliche Dienste (ed.), No. 83/08 (12 December 2008), p. 2.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf; Frick, Wilhelm; Heß, Rudolf (5 November 1935). Verordnung über das Hoheitszeichen des Reichs vom 5. November 1935 [Regulation concerning the national emblem of the reich of 5 November 1935]. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hitler, Adolf; Frick, Wilhelm; Heß, Rudolf (7 March 1936). Verordnung über die Gestaltung Hoheitszeichen des Reichs vom 7.März 1936 [Regulation concerning the design of the national emblem of the reich of 7 March 1936]. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- Ströhl, Hugo Gerard (1897), Deutsche Wappenrolle (in German) (Reprint Cologne ed.), Stuttgart, ISBN 3-89836-545-X

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Laitenberger, Birgit; Bassier, Maria (2000), Wappen und Flaggen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und ihrer Länder (in German) (5th revised ed.), Cologne, ISBN 3-452-24262-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link).

External links

Media related to Bundesadler at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bundesadler at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Reichsadler at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Reichsadler at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Coats of arms of Holy Roman Emperors at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Coats of arms of Holy Roman Emperors at Wikimedia Commons

Below is an overview table of the relationships of the House of Hohenzollern:

Swabian senior branch

The senior Swabian[1] branch of the House of Hohenzollern was founded by Frederick II, Burgrave of Nuremberg.

Ruling the minor German principalities of Hechingen, Sigmaringen and Haigerloch, this branch of the family decided to remain Roman Catholic and from 1567 onwards split into the Hohenzollern-Hechingen, Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen and Hohenzollern-Haigerloch branches. Romanian branch of this family became Orthodox, starting from Ferdinand's I children. When the last count of Hohenzollern, Charles I of Hohenzollern (1512–1579) died, the territory was to be divided up between his three sons:

- Eitel Frederick IV of Hohenzollern-Hechingen (1545–1605)

- Charles II of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (1547–1606)

- Christopher of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch (1552–1592)

They never expanded from these three Swabian principalities, which was one of the reasons they became relatively unimportant in German history for much of their existence. However, they kept royal lineage and married members of the great royal European houses.

In 1767 the principality of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch was incorporated into the other two principalities. In 1850, the princes of both Hohenzollern-Hechingen and Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen abdicated their thrones, and their principalities were incorporated as the Prussian province of Hohenzollern.

The last ruling Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, Karl Anton, would later serve as Minister-President of Prussia between 1858 and 1862.

The Hohenzollern-Hechingen finally became extinct in 1869. A descendent of this branch was Sophie Chotek, wife of Archduke Francis Ferdinand of Austria-Este.

However, a member of the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen family, Charles Eitel, second son of prince Karl Anton, was chosen to become prince of Romania as Charles I in 1866. In 1881 Charles I became the first king of the Romanians.

Charles' older brother, Leopold, was offered the Spanish throne after a revolt removed queen Isabella II in 1870. Although encouraged by Bismarck to accept it, Leopold backed down once France's Emperor, Napoleon III, stated his objection. Despite this, France still declared war, beginning the Franco-Prussian war.

Charles I had only a daughter who died very young, so Leopold's younger son Ferdinand I would succeed his uncle as king of the Romanians in 1914, and his descendants continued to rule in Romania until the end of the monarchy in 1947.

In modern times this branch has been represented only by the last king, Michael I of Romania, and his daughters. The descendants of Leopold's oldest son William continue to use the titles of prince or princess of Hohenzollern.

King Michael renounced his connection in 2011.[2]

Counts of Hohenzollern (1204–1575)

In 1204, the County of Hohenzollern was established out of the fusion of the County of Zollern and the Burgraviate of Nuremberg.

- 1204–1251/1255: Frederick IV, also Burgrave of Nuremberg as Frederick II until 1218

- 1251/1255–1289: Frederick V

- 1289–1298: Frederick VI

- 1298–1309: Frederick VII

- 1309–1333: Frederick VIII

- 1333–1377: Frederick IX

- 1377–1401: Frederick XI

- 1401–1426: Frederick XII

- 1426–1439: Eitel Frederick I

- 1439–1488: Jobst Nikolaus I

- 1488–1512: Eitel Frederick II

- 1512–1525: Eitel Frederick III

- 1525–1575: Charles I

In 1575 the County of Hohenzollern was split in two Counties with allodial rights, Hohenzollern-Hechingen and Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.

Counts of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch (1567–1630 and 1681–1767)

The County of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch was established in 1567 without allodial rights

- 1575–1601 : Christopher of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch

- 1601–1623 : John Christopher, Count of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch

- 1601–1630 : Charles, Count of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch

Between 1630 and 1681 the county was temporarily integrated into the principality of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.

- 1681–1702: Francis Anthony, Count of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch

- 1702–1750: Ferdinand Leopold, Count of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch

- 1750–1767: Francis Christopher Anton of Hohenzollern-Haigerloch

With the death of Francis Christoph Anton, the county of Hohenzollern-Haigenloch was definitely absorbed into the principality of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen in 1767.

Counts, later Princes of Hohenzollern-Hechingen (1576–1623–1850)

The County of Hohenzollern-Hechingen was established in 1576 with allodial rights.

- Eitel Frederick IV (1576–1605)

- John George (1605–1623) (raised to Prince in 1623)

- Eitel Friedrich V (1623–1661) (also count of Hohenzollern-Hechingen)

- Philipp Christoph Friedrich (1661–1671)

- Frederick William (1671–1735)

- Frederick Louis (1735–1750)

- Josef Friedrich Wilhelm (1750–1798)

- Hermann (1798–1810)

- Friedrich (1810–1838)

- Konstantin (1838–1850)

In 1850 the principality was sold to the Franconian branch of the family and incorporated into the Kingdom of Prussia. The branch became extinct in dynastic line with Konstantin's death in 1869.

Counts, later Princes of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (1576–1623–1849)

The County of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen was established in 1576 with allodial rights and a seat at Sigmaringen Castle.

- Karl II (1576–1606)

- John (1606–1638) (elevated to Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen in 1623)

- Meinrad I (1638–1681)

- Maximilian I (1681–1689)

- Meinrad I (1689–1715)

- Joseph Frederick Ernest (1715–1769)

- Charles Frederick (1769–1785)

- Anton Aloys (1785–1831)

- Karl III (1831–1848)

- Karl Anton (1848–1849)

In 1850 the principality was sold to the Franconian branch of the family and incorporated into the kingdom of Prussia. Nevertheless, the family continued to use the princely title of Fürsten von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen until 1869 and still use the title of Fürsten von Hohenzollern.

Kings of the Romanians

Reigning (1866–1947)

The Principality of Romania was established in 1862, after the Ottoman vassal states of Wallachia and Moldavia had been united in 1859 under Alexandru Ioan Cuza as Prince of Romania in a personal union.

He was deposed in 1866 by the Romanian parliament which then invited a German prince of the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen family, Charles, to become Prince of Romania under the name Prince Carol.

In 1881 the Principality of Romania was proclaimed a Kingdom. For dynastic reasons, Carol's grandchildren renounced Catholicism and were brought up in the Romanian Orthodox Church.

- 1866–1914: Charles I (titled as Prince until 1881)

- 1914–1927: Ferdinand

- 1927–1930: Michael

- 1930–1940: Charles II

- 1940–1947: Michael (again)

In 1947 the Kingdom of Romania was abolished and replaced with the People's Republic of Romania.

Succession (1947 until today)

Michael has retained his claim on the defunct Romanian throne. At present, the claim is not recognised by Romania, a republic. At 10 May 2011, Michael severed all of the dynastic and historical ties between the House of Romania and the House of Hohenzollern.[3]

House of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen

The princely House of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen never relinquished their claims to the princely throne of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen or the royal throne of Romania. Because the last reigning king of the Romanians, Michael I, has no male issue, upon his death the claim will devolve to the head of the House of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen (or to the king's female line descendants, if one follows the amended Romanian house laws).

- 1849–1885: Karl Anton, Prince of Hohenzollern

- 1885–1905: Leopold, Prince of Hohenzollern

- 1905–1927: Wilhelm, Prince of Hohenzollern

- 1927–1965: Friedrich, Prince of Hohenzollern

- 1965–2010 : Friedrich Wilhelm, Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen

- 2010 - current : Karl Friedrich, Prince of Hohenzollern

- heir apparent: Alexander, Hereditary Prince of Hohenzollern

The head of the family is styled His Serene Highness The Prince of Hohenzollern.

See also

- Kings of Germany family tree. The Hohenzollerns were the 15th dynasty to rule Germany and were related by marriage to all the others.

- Coat of arms of Prussia

- Coat of arms of Germany

- House Order of Hohenzollern

- Heil dir im Siegerkranz

- Order of the Black Eagle and SUUM CUIQUE

- Order of the Red Eagle and SINCERE ET CONSTANTE

- Wilhelm-Orden

- Order of the Crown (Prussia) and GOTT MIT UNS

- Iron Cross

References

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

autogenerated178was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "King Michael I broke ties with historical and dynastic House of Hohenzollern" in Adevarul - News Bucharest, 10 May 2011

- ^ "Romania's former King Michael ends ties with German Hohenzollern dynasty". The Canadian Press. Retrieved 2011-05-11.

External links

- Official site of the imperial House of Germany and royal House of Prussia

- Official site of the princely House of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen

- Official site of the royal house of Romania

- Genealogy of the Hohenzollern

- Marek, Miroslav. "Genealogy of the Hohenzollerns from Genealogy.eu". Genealogy.EU.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=

Warning: Default sort key "House Of Hohenzollern" overrides earlier default sort key "Germany, Federal Republic of, Coat of arms of the".