House

| Part of a series on |

| Living spaces |

|---|

|

A house is a single-unit residential building. It may range in complexity from a rudimentary hut to a complex structure of wood, masonry, concrete or other material, outfitted with plumbing, electrical, and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems.[1][2] Houses use a range of different roofing systems to keep precipitation such as rain from getting into the dwelling space. Houses generally have doors or locks to secure the dwelling space and protect its inhabitants and contents from burglars or other trespassers. Most conventional modern houses in Western cultures will contain one or more bedrooms and bathrooms, a kitchen or cooking area, and a living room. A house may have a separate dining room, or the eating area may be integrated into the kitchen or another room. Some large houses in North America have a recreation room. In traditional agriculture-oriented societies, domestic animals such as chickens or larger livestock (like cattle) may share part of the house with humans.

The social unit that lives in a house is known as a household. Most commonly, a household is a family unit of some kind, although households may also have other social groups, such as roommates or, in a rooming house, unconnected individuals, that typically use a house as their home. Some houses only have a dwelling space for one family or similar-sized group; larger houses called townhouses or row houses may contain numerous family dwellings in the same structure. A house may be accompanied by outbuildings, such as a garage for vehicles or a shed for gardening equipment and tools. A house may have a backyard, a front yard or both, which serve as additional areas where inhabitants can relax, eat, or exercise.

Etymology

The English word house derives directly from the Old English word hus, meaning "dwelling, shelter, home, house," which in turn derives from Proto-Germanic husan (reconstructed by etymological analysis) which is of unknown origin.[3] The term house itself gave rise to the letter 'B' through an early Proto-Semitic hieroglyphic symbol depicting a house. The symbol was called "bayt", "bet" or "beth" in various related languages, and became beta, the Greek letter, before it was used by the Romans.[4] Beit in Arabic means house, while in Maltese bejt refers to the roof of the house.[5][6]

Elements

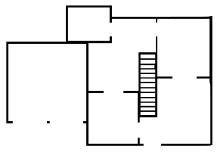

Layout

Ideally, architects of houses design rooms to meet the needs of the people who will live in the house. Feng shui, originally a Chinese method of moving houses according to such factors as rain and micro-climates, has recently expanded its scope to address the design of interior spaces, with a view to promoting harmonious effects on the people living inside the house, although no actual effect has ever been demonstrated. Feng shui can also mean the "aura" in or around a dwelling, making it comparable to the real estate sales concept of "indoor-outdoor flow".

The square footage of a house in the United States reports the area of "living space", excluding the garage and other non-living spaces. The "square metres" figure of a house in Europe reports the area of the walls enclosing the home, and thus includes any attached garage and non-living spaces.[7] The number of floors or levels making up the house can affect the square footage of a home.

Humans often build houses for domestic or wild animals, often resembling smaller versions of human domiciles. Familiar animal houses built by humans include birdhouses, hen houses and dog houses, while housed agricultural animals more often live in barns and stables.

Parts

Many houses have several large rooms with specialized functions and several very small rooms for other various reasons. These may include a living/eating area, a sleeping area, and (if suitable facilities and services exist) separate or combined washing and lavatory areas. Some larger properties may also feature rooms such as a spa room, indoor pool, indoor basketball court, and other 'non-essential' facilities. In traditional agriculture-oriented societies, domestic animals such as chickens or larger livestock often share part of the house with humans. Most conventional modern houses will at least contain a bedroom, bathroom, kitchen or cooking area, and a living room. The names of parts of a house often echo the names of parts of other buildings, but could typically include:

- Alcove

- Atrium

- Attic

- Basement/cellar

- Bathroom

- Bedroom (or nursery)

- Box-room / storage room

- Conservatory

- Dining room

- Family room or den

- Fireplace

- Foyer

- Front room

- Garage

- Hallway / passage / Vestibule

- Hearth

- Home-office or study

- Kitchen

- Larder

- Laundry room

- Library

- Living room

- Loft

- Nook

- Pantry

- Parlour

- Porch

- Recreation room / rumpus room / television room

- Shrines to serve the religious functions associated with a family

- Stairwell

- Sunroom

- Swimming pool

- Window

- Workshop

- utility room

History

Little is known about the earliest origin of the house and its interior; however, it can be traced back to the simplest form of shelters. An exceptionally well-preserved house dating to the fifth millennium BC and with its contents still preserved was for example excavated at Tell Madhur in Iraq.[8] Roman architect Vitruvius' theories have claimed the first form of architecture as a frame of timber branches finished in mud, also known as the primitive hut.[9] Philip Tabor later states the contribution of 17th century Dutch houses as the foundation of houses today.

As far as the idea of the home is concerned, the home of the home is the Netherlands. This idea's crystallization might be dated to the first three-quarters of the 17th century, when the Dutch Netherlands amassed the unprecedented and unrivalled accumulation of capital, and emptied their purses into domestic space.[10]

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, the Manor Houses facilitated different activities and events. Furthermore, the houses accommodated numerous people, including family, relatives, employees, servants and their guests.[9] Their lifestyles were largely communal, as areas such as the Great Hall enforced the custom of dining and meetings and the Solar intended for shared sleeping beds.[11]

During the 15th and 16th centuries, the Italian Renaissance Palazzo consisted of plentiful rooms of connectivity. Unlike the qualities and uses of the Manor Houses, most rooms of the palazzo contained no purpose, yet were given several doors. These doors adjoined rooms in which Robin Evans describes as a "matrix of discrete but thoroughly interconnected chambers."[12] The layout allowed occupants to freely walk room to room from one door to another, thus breaking the boundaries of privacy.

- "Once inside it is necessary to pass from one room to the next, then to the next to traverse the building. Where passages and staircases are used, as inevitably they are, they nearly always connect just one space to another and never serve as general distributors of movement. Thus, despite the precise architectural containment offered by the addition of room upon room, the villa was, in terms of occupation, an open plan, relatively permeable to the numerous members of the household."[12] Although very public, the open plan encouraged sociality and connectivity for all inhabitants.[9]

An early example of the segregation of rooms and consequent enhancement of privacy may be found in 1597 at the Beaufort House built in Chelsea, London. It was designed by English architect John Thorpe who wrote on his plans, "A Long Entry through all".[13] The separation of the passageway from the room developed the function of the corridor. This new extension was revolutionary at the time, allowing the integration of one door per room, in which all universally connected to the same corridor. English architect Sir Roger Pratt states "the common way in the middle through the whole length of the house, [avoids] the offices from one molesting the other by continual passing through them."[14] Social hierarchies within the 17th century were highly regarded, as architecture was able to epitomize the servants and the upper class. More privacy is offered to the occupant as Pratt further claims, "the ordinary servants may never publicly appear in passing to and fro for their occasions there."[14] This social divide between rich and poor favored the physical integration of the corridor into housing by the 19th century.

Sociologist Witold Rybczynski wrote, "the subdivision of the house into day and night uses, and into formal and informal areas, had begun."[15] Rooms were changed from public to private as single entryways forced notions of entering a room with a specific purpose.[9]

Industrial Revolution

Compared to the large scaled houses in England and the Renaissance, the 17th Century Dutch house was smaller, and was only inhabited by up to four to five members.[9] This was because they embraced "self-reliance"[9] in contrast to the dependence on servants, and a design for a lifestyle centered on the family. It was important for the Dutch to separate work from domesticity, as the home became an escape and a place of comfort. This way of living and the home has been noted as highly similar to the contemporary family and their dwellings.

By the end of the 17th century, the house layout was transformed to become employment-free, enforcing these ideas for the future. This came in favour for the Industrial Revolution, gaining large-scale factory production and workers.[9] The house layout of the Dutch and its functions are still relevant today.

19th and 20th centuries

In the American context, some professions, such as doctors, in the 19th and early 20th century typically operated out of the front room or parlor or had a two-room office on their property, which was detached from the house. By the mid 20th century, the increase in high-tech equipment created a marked shift whereby the contemporary doctor typically worked from an office or hospital.[16][17]

Technology and electronic systems has caused privacy issues and issues with segregating personal life from remote work. Technological advances of surveillance and communications allow insight of personal habits and private lives.[9] As a result, the "private becomes ever more public, [and] the desire for a protective home life increases, fuelled by the very media that undermine it," writes Jonathan Hill.[9] Work has been altered by the increase of communications. The "deluge of information"[9] has expressed the efforts of work conveniently gaining access inside the house. Although commuting is reduced, the desire to separate working and living remains apparent.[9] On the other hand, some architects have designed homes in which eating, working and living are brought together.

Gallery

-

Modern land house in Germany

-

Modern suburban house in Poland

-

Farmhouse in Bhutan

-

Khmer house in Cambodia

-

Traditional house in Colombia

-

Minangkabau traditional house in Indonesia

-

Traditional village house in Banaue, Philippines

-

House in Brgule, Serbia

-

Traditional house in Japan

-

Traditional two-story tin shed house in Bangladesh

-

Traditional stone house in Serbia

-

A traditional Kurdish stone house

-

Energy-efficient houses in Amersfoort, Netherlands

-

A house in Ontario, Canada

-

A decorated house in Utrecht, Netherlands

-

A single living house in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

-

Old and new houses side by side in Dallas

-

Traditional house in Darchula District Nepal

-

A standard house in Ghana

Construction

In many parts of the world, houses are constructed using scavenged materials. In Manila's Payatas neighborhood, slum houses are often made of material sourced from a nearby garbage dump.[18] In Dakar, it is common to see houses made of recycled materials standing atop a mixture of garbage and sand which serves as a foundation. The garbage-sand mixture is also used to protect the house from flooding.[19]

These homes are often illegally built and without electricity, proper sanitation and taps for drinking water.

In the United States, modern house construction techniques include light-frame construction (in areas with access to supplies of wood) and adobe or sometimes rammed-earth construction (in arid regions with scarce wood-resources). Some areas use brick almost exclusively, and quarried stone has long provided foundations and walls. To some extent, aluminum and steel have displaced some traditional building materials. Increasingly popular alternative construction materials include insulating concrete forms (foam forms filled with concrete), structural insulated panels (foam panels faced with oriented strand board or fiber cement), light-gauge steel, and steel framing. More generally, people often build houses out of the nearest available material, and often tradition or culture govern construction-materials, so whole towns, areas, counties or even states/countries may be built out of one main type of material. For example, a large portion of American houses use wood, while most British and many European houses use stone, brick, or mud.

In the early 20th century, some house designers started using prefabrication. Sears, Roebuck & Co. first marketed their Sears Catalog Homes to the general public in 1908. Prefab techniques became popular after World War II. First small inside rooms framing, then later, whole walls were prefabricated and carried to the construction site. The original impetus was to use the labor force inside a shelter during inclement weather. More recently, builders have begun to collaborate with structural engineers who use finite element analysis to design prefabricated steel-framed homes with known resistance to high wind loads and seismic forces. These newer products provide labor savings, more consistent quality, and possibly accelerated construction processes.

Lesser-used construction methods have gained (or regained) popularity in recent years. Though not in wide use, these methods frequently appeal to homeowners who may become actively involved in the construction process. They include:

In the developed world, energy-conservation has grown in importance in house design. Housing produces a major proportion of carbon emissions (studies have shown that it is 30% of the total in the United Kingdom).[20]

Development of a number of low-energy building types and techniques continues. They include the zero-energy house, the passive solar house, the autonomous buildings, the super insulated houses and houses built to the Passivhaus standard.

Legal issues

Buildings with historical importance have legal restrictions. New houses in the UK are not covered by the Sale of Goods Act. When purchasing a new house, the buyer has different legal protection than when buying other products. New houses in the UK are covered by a National House Building Council guarantee.

Identification and symbolism

With the growth of dense settlement, humans designed ways of identifying houses and parcels of land. Individual houses sometimes acquire proper names, and those names may acquire in their turn considerable emotional connotations. A more systematic and general approach to identifying houses may use various methods of house numbering.

Houses may express the circumstances or opinions of their builders or their inhabitants. Thus, a vast and elaborate house may serve as a sign of conspicuous wealth whereas a low-profile house built of recycled materials may indicate support of energy conservation. Houses of particular historical significance (former residences of the famous, for example, or even just very old houses) may gain a protected status in town planning as examples of built heritage or of streetscape. Commemorative plaques may mark such structures. Home ownership provides a common measure of prosperity in economics. Contrast the importance of house-destruction, tent dwelling and house rebuilding in the wake of many natural disasters.

See also

Building

Functions

Types

- Boarding house

- Earth sheltering

- Home automation

- Housing estate

- Housing in Japan

- Hurricane-proof house

- Lodging

- Lustron house

- Mobile home

- Modular home

- Slope house

- Summer house

- Tiny house

Economics

Miscellaneous

Institutions

Lists

References

- ^ Schoenauer, Norbert (2000). 6,000 Years of Housing (rev. ed.) (New York: W.W. Norton & Company).

- ^ "housing papers" (PDF). clerk.house.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 17, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Sacks, David (2004). Letter perfect: the marvelous history of our alphabet from A to Z. Random House Digital. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-7679-1173-3.

- ^ Grima, Noel (July 24, 2017). "The Book That Came Back from Death." Independent.com.mt. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ http://melitensiawth.nl/index/Journal%20of%20Maltese%20Studies/JMS.16.1986/02s.pdf [dead link]

- ^ Iyyer, Chaitanya (2009). Land Management: Challenges and Strategies (First ed.). Global India Publications Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-9380228488.

- ^ Curtis, John (1982). Fifty years of Mesopotamian discovery : the work of the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 1932-1982. London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq. ISBN 0-903472-05-8. OCLC 10923961.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hill, Jonathan, "Immaterial Architecture", New York: Routledge, 2006.

- ^ Tabor, Philip, "Striking Home: The Telematic Assault on Identity". Published in Jonathan Hill, editor, Occupying Architecture: Between the Architect and the User.

- ^ "Manor House". Middle-ages.org.uk. May 16, 2007. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Evans, Robin "Translations from Drawing to Building: Figures, Doors and Passages" London: Architectural Associations Publications 2005

- ^ Summerson, John "The Book Of Architecture of John Thorpe in Sir John Soane's museum: 40th Volume of the Walpole Society" England: The Society 1964

- ^ a b Pratt, Sir Roger "Sir R. Pratt on Architecture" 1928

- ^ Rybczynski, Witold (1987). Home: A Short History of An Idea. London: Penguin. p. 56. ISBN 0-14-010231-0.

- ^ "Doctor's and Dentist's Offices". Melnick Medical Museum. January 29, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "Doctor's residence and surgery, No 8 Milford Ave, Randwick, New South Wales, photograph taken by Sam Hood for LJ Hooker", State Library of New South Wales, Home and Away 11690, FL1472550, 1951. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ Brown, Andy (2009). "Below the poverty line: living on a garbage dump". Real Lives. UNICEF. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2013.

Slum houses, often made of materials scavenged from the dump site...

- ^ Nossiter, Adam (May 2, 2009). "In Senegal, Building on Perilous Layers of Trash". The New York Times.

- ^ "Energy Performance Certificates – what they are : Directgov – Home and community". Direct.gov.uk. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

External links

- Housing through the centuries, animation by The Atlantic