Vertical and horizontal

In astronomy, geography, and related sciences and contexts, a direction or plane passing by a given point is said to be vertical if it contains the local gravity direction at that point.[1]

Conversely, a direction or plane is said to be horizontal (or leveled) if it is perpendicular to the vertical direction. In general, something that is vertical can be drawn from up to down (or down to up), such as the y-axis in the Cartesian coordinate system.

Historical definition

[edit]The word horizontal is derived from the Latin horizon, which derives from the Greek ὁρῐ́ζων, meaning 'separating' or 'marking a boundary'.[2] The word vertical is derived from the late Latin verticalis, which is from the same root as vertex, meaning 'highest point' or more literally the 'turning point' such as in a whirlpool.[3]

Girard Desargues defined the vertical to be perpendicular to the horizon in his 1636 book Perspective.

Geophysical definition

[edit]The plumb line and spirit level

[edit]

In physics, engineering and construction, the direction designated as vertical is usually that along which a plumb-bob hangs. Alternatively, a spirit level that exploits the buoyancy of an air bubble and its tendency to go vertically upwards may be used to test for horizontality. A water level device may also be used to establish horizontality.

Modern rotary laser levels that can level themselves automatically are robust sophisticated instruments and work on the same fundamental principle.[4][5]

The spherical Earth

[edit]

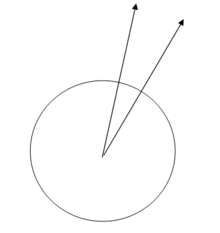

When the curvature of the Earth is taken into account, the concepts of vertical and horizontal take on yet another meaning. On the surface of a smoothly spherical, homogenous, non-rotating planet, the plumb bob picks out as vertical the radial direction. Strictly speaking, it is now no longer possible for vertical walls to be parallel: all verticals intersect. This fact has real practical applications in construction and civil engineering, e.g., the tops of the towers of a suspension bridge are further apart than at the bottom. [6]

Also, horizontal planes can intersect when they are tangent planes to separated points on the surface of the Earth. In particular, a plane tangent to a point on the equator intersects the plane tangent to the North Pole at a right angle. (See diagram). Furthermore, the equatorial plane is parallel to the tangent plane at the North Pole and as such has claim to be a horizontal plane. But it is. at the same time, a vertical plane for points on the equator. In this sense, a plane can, arguably, be both horizontal and vertical, horizontal at one place, and vertical at another.

Further complications

[edit]For a spinning earth, the plumb line deviates from the radial direction as a function of latitude.[7] Only on the equator and at the North and South Poles does the plumb line align with the local radius. The situation is actually even more complicated because Earth is not a homogeneous smooth sphere. It is a non homogeneous, non spherical, knobby planet in motion, and the vertical not only need not lie along a radial, it may even be curved and be varying with time. On a smaller scale, a mountain to one side may deflect the plumb bob away from the true zenith.[8]

On a larger scale the gravitational field of the Earth, which is at least approximately radial near the Earth, is not radial when it is affected by the Moon at higher altitudes.[9][10]

Independence of horizontal and vertical motions

[edit]Neglecting the curvature of the earth, horizontal and vertical motions of a projectile moving under gravity are independent of each other.[11] Vertical displacement of a projectile is not affected by the horizontal component of the launch velocity, and, conversely, the horizontal displacement is unaffected by the vertical component. The notion dates at least as far back as Galileo.[12]

When the curvature of the Earth is taken into account, the independence of the two motion does not hold. For example, even a projectile fired in a horizontal direction (i.e., with a zero vertical component) may leave the surface of the spherical Earth and indeed escape altogether.[13]

Mathematical definition

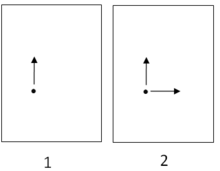

[edit]In two dimensions

[edit]

In the context of a 1-dimensional orthogonal Cartesian coordinate system on a Euclidean plane, to say that a line is horizontal or vertical, an initial designation has to be made. One can start off by designating the vertical direction, usually labelled the Y direction.[14] The horizontal direction, usually labelled the X direction,[15] is then automatically determined. Or, one can do it the other way around, i.e., nominate the x-axis, in which case the y-axis is then automatically determined. There is no special reason to choose the horizontal over the vertical as the initial designation: the two directions are on par in this respect.

The following hold in the two-dimensional case:

- Through any point P in the plane, there is one and only one vertical line within the plane and one and only one horizontal line within the plane. This symmetry breaks down as one moves to the three-dimensional case.

- A vertical line is any line parallel to the vertical direction. A horizontal line is any line normal to a vertical line.

- Horizontal lines do not cross each other.

- Vertical lines do not cross each other.

Not all of these elementary geometric facts are true in the 3-D context.

In three dimensions

[edit]In the three-dimensional case, the situation is more complicated as now one has horizontal and vertical planes in addition to horizontal and vertical lines. Consider a point P and designate a direction through P as vertical. A plane which contains P and is normal to the designated direction is the horizontal plane at P. Any plane going through P, normal to the horizontal plane is a vertical plane at P. Through any point P, there is one and only one horizontal plane but a multiplicity of vertical planes. This is a new feature that emerges in three dimensions. The symmetry that exists in the two-dimensional case no longer holds.

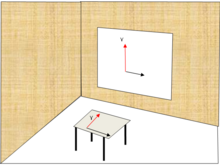

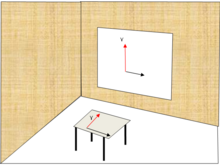

In the classroom

[edit]

In the 2-dimension case, as mentioned already, the usual designation of the vertical coincides with the y-axis in co-ordinate geometry. This convention can cause confusion in the classroom. For the teacher, writing perhaps on a white board, the y-axis really is vertical in the sense of the plumbline verticality but for the student the axis may well lie on a horizontal table.

Discussion

[edit]This article may need to be cleaned up. It has been merged from Horizontal plane. |

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (July 2018) |

Although the word horizontal is commonly used in daily life and language (see below), it is subject to many misconceptions.

- The concept of horizontality only makes sense in the context of a clearly measurable gravity field, i.e., in the 'neighborhood' of a planet, star, etc. When the gravity field becomes very weak (the masses are too small or too distant from the point of interest), the notion of being horizontal loses its meaning.

- A plane is horizontal only at the chosen point. Horizontal planes at two separate points are not parallel, they intersect.

- In general, a horizontal plane will only be perpendicular to a vertical direction if both are specifically defined with respect to the same point: a direction is only vertical at the point of reference. Thus both horizontality and verticality are strictly speaking local concepts, and it is always necessary to state to which location the direction or the plane refers to. (1) the same restriction applies to the straight lines contained within the plane: they are horizontal only at the point of reference, and (2) those straight lines contained in the plane but not passing by the reference point are not necessarily horizontal anywhere.

- In reality, the gravity field of a heterogeneous planet such as Earth is deformed due to the inhomogeneous spatial distribution of materials with different densities. Actual horizontal planes are thus not even parallel even if their reference points are along the same vertical line, since a vertical line is slightly curved.

- At any given location, the total gravitational force is not quite constant over time, because the objects that generate the gravity are moving. For instance, on Earth the horizontal plane at a given point (as determined by a pair of spirit levels) changes with the position of the Moon (air, sea and land tides).

- On a rotating planet such as Earth, the strictly gravitational pull of the planet (and other celestial objects such as the Moon, the Sun, etc.) is different from the apparent net force (e.g., on a free-falling object) that can be measured in the laboratory or in the field. This difference is the centrifugal force associated with the planet's rotation. This is a fictitious force: it only arises when calculations or experiments are conducted in non-inertial frames of reference, such as the surface of the Earth.

In general or in practice, something that is horizontal can be drawn from left to right (or right to left), such as the x-axis in the Cartesian coordinate system.[citation needed]

Practical use in daily life

[edit]

The concept of a horizontal plane is thus anything but simple, although, in practice, most of these effects and variations are rather small: they are measurable and can be predicted with great accuracy, but they may not greatly affect our daily life.

This dichotomy between the apparent simplicity of a concept and an actual complexity of defining (and measuring) it in scientific terms arises from the fact that the typical linear scales and dimensions of relevance in daily life are 3 orders of magnitude (or more) smaller than the size of the Earth. Hence, the world appears to be flat locally, and horizontal planes in nearby locations appear to be parallel. Such statements are nevertheless approximations; whether they are acceptable in any particular context or application depends on the applicable requirements, in particular in terms of accuracy. In graphical contexts, such as drawing and drafting and Co-ordinate geometry on rectangular paper, it is very common to associate one of the dimensions of the paper with a horizontal, even though the entire sheet of paper is standing on a flat horizontal (or slanted) table. In this case, the horizontal direction is typically from the left side of the paper to the right side. This is purely conventional (although it is somehow 'natural' when drawing a natural scene as it is seen in reality), and may lead to misunderstandings or misconceptions, especially in an educational context.

See also

[edit]- Cartesian coordinate system

- Coordinate system

- Horizon

- Horizontal angle

- Horizontal coordinate system

- Horizontal position representation

- Local tangent plane

- Northing and easting

- Tilted plane

- Transverse plane

- Vertical and horizontal (radio propagation)

- Vertical circle

- Vertical position

- Zenith

- Zenith angle (vertical angle)

References and notes

[edit]- ^ Hofmann-Wellenhof, B.; Moritz, H. (2006). Physical Geodesy (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-211-33544-4.

- ^ "horizontal". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "vertical". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Laser Levels".

- ^ "How Does a Spirit Level Work?". Physics Forums | Science Articles, Homework Help, Discussion. 25 December 2011.

- ^ Encyclopedia.com. In very long bridges, it may be necessary to take the Earth's curvature into account when designing the towers. For example, in the New York's Verrazano Narrows rivers, the towers, which are 700 ft (215 m) tall and stand 4260 ft (298 m) apart, are about 1.75 in (4.5 cm) farther apart at the top than they are at the bottom.

- ^ "Working in the Rotating Reference Frame of the Earth" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-06. Retrieved 2013-03-11.

- ^ Such a deflection was measured by Nevil Maskelyne. See Maskelyne, N. (1775). "An Account of Observations Made on the Mountain Schiehallion for Finding Its Attraction". Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. 65 (0): 500–542. doi:10.1098/rstl.1775.0050. Charles Hutton used the observed value to determine the density of the Earth.

- ^ Cornish, Neil J. "The Lagrangian Points" (PDF). Montana State University – Department of Physics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ For an example of curved field lines, see The gravitational field of a cube by James M. Chappell, Mark J. Chappell, Azhar Iqbal, Derek Abbott for an example of curved gravitational field. arXiv:1206.3857 [physics.class-ph] (or arXiv:1206.3857v1 [physics.class-ph] for this version)

- ^ Salters Hornerns Advanced Physics Project, As Student Book, Edexcel Pearson, London, 2008, p. 48.

- ^ See Galileo's discussion of how bodies rise and fall under gravity on a moving ship in his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems(trans. S. Drake). University of California Press, Berkeley, 1967, pp. 186–187.

- ^ See Harris Benson University Physics, New York 1991, page 268.

- ^ "Horizontal and Vertical Lines". www.mathsteacher.com.au.

- ^ For a definition of "Horizontal axis" see Math Dictionary at www.icoachmath.com

Further reading

[edit]- Brennan, David A.; Esplen, Matthew F.; Gray, Jeremy J. (1998), Geometry, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-59787-0

- Murray R Spiegel, (1987), Theory and Problems of Theoretical Mechanics, Singapore, Mcgraw Hill's: Schaum's, ISBN 0-07-084357-0