Holborn tube station

| Holborn | |

|---|---|

Station entrance | |

| Location | Holborn |

| Local authority | London Borough of Camden |

| Managed by | London Underground |

| Number of platforms | 4 |

| Fare zone | 1 |

| London Underground annual entry and exit | |

| 2019 | |

| 2020 | |

| 2021 | |

| 2022 | |

| 2023 | |

| Key dates | |

| 1906 | Opened (GNP&BR) |

| 1907 | Opened (Aldwych branch) |

| 1933 | Opened (Central line) |

| 1994 | Closed (Aldwych branch) |

| Other information | |

| External links | |

| Coordinates | 51°31′03″N 0°07′12″W / 51.5174°N 0.1201°W |

Holborn (/ˈhoʊbərn/ HOH-bə(r)n)[a] is a London Underground station in Holborn, Central London, located at the junction of High Holborn and Kingsway.[10] It is served by the Central and Piccadilly lines. On the Central line the station is between Tottenham Court Road and Chancery Lane stations, and on the Piccadilly line it is between Covent Garden and Russell Square stations. The station is in Travelcard Zone 1. Close by are the British Museum, Lincoln's Inn Fields, Red Lion Square, Bloomsbury Square, London School of Economics and Sir John Soane's Museum.

Located at the junction of two earlier tube railway schemes, the station was opened in 1906 by the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway (GNP&BR). The station entrances and below ground circulation were largely reconstructed for the introduction of escalators and the opening of Central line platforms in 1933, making the station the only interchange between the lines. Before 1994, Holborn was the northern terminus of the short and little-frequented Piccadilly line branch to Aldwych and two platforms originally used for this service are disused. One of the disused platforms has been used for location filming when a London Underground station platform is needed.

While the two disused platforms are now closed to the public, they can be still be seen on a "Hidden London" guided tour held by London Transport Museum.[11]

Planning

[edit]The station was planned by the Great Northern and Strand Railway (GN&SR), which had received parliamentary approval for a route from Wood Green station (now Alexandra Palace) to Strand in 1899.[12] After the GN&SR was taken over by the Brompton and Piccadilly Circus Railway (B&PCR) in September 1901, the two companies came under the control of Charles Yerkes' Metropolitan District Electric Traction Company before being transferred to his new holding company, the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) in June 1902.[13] To connect the two companies' planned routes, the UERL obtained permission for new tunnels between Piccadilly Circus and Holborn. The companies were formally merged as the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway following parliamentary approval in November 1902.[14][15][16]

Construction

[edit]The linking of the GN&SR and B&PCR routes at Holborn meant that the section of the GN&SR south of Holborn became a branch from the main route. The UERL began constructing the main route in July 1902. Progress was rapid, so that it was largely complete by the Autumn of 1906.[17] Construction of the branch was delayed while the London County Council carried out slum clearances to construct its new road Kingsway and the tramway subway running beneath it and while the UERL decided how the junction between the main route and the branch would be arranged at Holborn.[18]

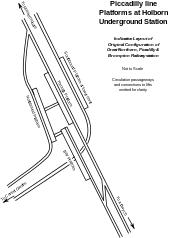

When originally planned by the GN&SR, Holborn station was to have just two platforms. The first GNP&BR plan for the station would have seen the two platforms shared by trains on the main route and by the shuttle service on the branch with the junctions between the tunnels south of the station. The interference that shuttle trains would have caused to services on the main route led to a redesign so that two northbound platforms were provided, one for the main line and one for the branch line, with a single southbound platform. The junctions between the two northbound tunnels would have been 75 metres (246 ft) north of the platforms.[19] When powers were sought to build the junction in 1905, the layout was changed again so that four platforms were to be provided. The southbound tunnel of the main route no longer connected to the branch, which was to be provided with an additional platform in a dead-end tunnel accessed from a crossover from the northbound branch tunnel. As built, for ease of passenger access, the branch's northbound tunnel ended in a dead-end platform adjacent to the northbound main line platform with the branch's southbound tunnel connected to the northbound main line tunnel.[20] To enable the southbound tunnel of the main route to avoid the branch tunnels, it was constructed at a lower level than the other tunnels and platforms. The tunnel towards Covent Garden (at this point heading south-west) passes under the branch tunnels.

As with most of the other GNP&BR stations, the station building was designed by Leslie Green,[10] though at Holborn the station frontage was, uniquely, constructed in stone rather than the standard red glazed terracotta. This was due to planning regulations imposed by the London County Council which required the use of stone for façades in Kingsway.[10] The station entrance and exit sections of the street façade were constructed in granite with the other parts of the ground and first floors in the same style, but using Portland stone.[10][21][failed verification – see discussion] The rest of the building above first floor level was constructed contemporaneously with the station. Access to the platform levels of the station was provided by trapezium-shaped electric lifts manufactured by Otis in America. These operated in pairs in shared circular shafts,[22][b] with an escape stair in a separate, smaller shaft.[10]

Although the station was constructed where the GNP&BR's tunnels crossed those of the Central London Railway (CLR, now the Central line) running under High Holborn,[c] no interchange between the two lines was made as the CLR's nearest station, British Museum, was 250 metres (820 ft) to the west. Passengers wishing to interchange between the two stations had to do so at street level.[26]

The station opened on 15 December 1906, although the opening of the branch was delayed until 30 November 1907.[27]

1930s station modernisation

[edit]

The street level interchange between the GNP&BR and CLR involving two sets of lifts was considered a weakness in the network. A below ground subway connection was considered in 1907. A proposal to enlarge the CLR's tunnels to create new platforms at Holborn station and to abandon British Museum station was included in a private bill submitted to parliament by the CLR in November 1913,[28] although the First World War prevented any works taking place.[26]

Like many other central London Underground stations, Holborn was modernised in the early 1930s to replace the lifts with escalators.[10] The station frontages on Kingsway and High Holborn were partially reconstructed to modernist designs by Charles Holden with the granite elements replaced with plain Portland stone façades perforated with glazed screens.[10] The lifts were removed and a spacious new ticket hall was provided giving access to a bank of four escalators down to an intermediate concourse for the Central line platforms.[10][21][24] A second bank of three escalators continues down to the Piccadilly line platforms.

To construct the new Central line platforms, the larger diameter station tunnels were manually excavated around the existing running tunnels whilst trains continued to run. When the excavations were complete, the original segmental tunnel linings were dismantled.[29] The new platforms came into use on 25 September 1933 replacing those of British Museum, which had closed the day before. As part of the modernisation the station was renamed Holborn (Kingsway) on 22 May 1933, but the suffix gradually dropped out of use and no longer appears on station signage or tube maps. It was displayed on the platform roundels until the 1980s.[27][d]

The new platforms at Holborn led to the number of passengers switching between the lines increasing tenfold by 1938.[26]

Mural additions in the 1980s

[edit]The station was redecorated in the 1980s, with platform walls lined with panels of enamelled metal forming murals designed by Allan Drummond that reference the British Museum. These murals reference Egyptian and Roman antiquities, with sarcophagi, statues and trompe-l'œil columns on the walls of the platform.[30]

Branch operations

[edit]

Initially, shuttle train services on the branch operated from the through platform at Holborn. At peak times, an additional train operated alternately in the branch's western tunnel from the bay platform at Holborn. During the first year of operation, a train for theatregoers operated late on Monday to Saturday evenings from Strand through Holborn and northbound to Finsbury Park; this was discontinued in October 1908.[31]

In March 1908, the off-peak shuttle service began to use the western tunnel on the branch, crossing between the two branch tunnels south of Holborn. Low usage led to the withdrawal of the second peak-hour shuttle and the eastern tunnel was taken out of use in 1914.[32] Sunday services ended in April 1917 and, in August of the same year, the eastern tunnel and the bay platform at Holborn were formally closed.[33] Passenger numbers on the branch remained low: when the branch was considered for closure in 1929, its annual usage was 1,069,650 and takings were £4,500.[34] The branch was again considered for closure in 1933, but remained open.[33]

Wartime efficiency measures led to the branch being closed temporarily on 22 September 1940, shortly after the start of The Blitz, and it was partly fitted out by the City of Westminster as an air-raid shelter. The tunnels were used to store items from the British Museum, including the Elgin Marbles. The branch reopened on 1 July 1946, but patronage did not increase.[35] In 1958, London Transport announced it would be closed. Again it survived, but the service was reduced in June 1958 to run only during Monday to Friday peak hours and Saturday morning and early afternoons.[36] The Saturday service was withdrawn in June 1962.[36]

After operating only during peak hours for more than 30 years, the closure announcement came on 4 January 1993. The original 1907 lifts at Aldwych required replacement at a cost of £3 million. This was not justifiable as only 450 passengers used the station each day and it was losing London Regional Transport £150,000 per year. The secretary of state for transport granted permission on 1 September 1994 to close the station and the branch closed on 30 September.[37]

After its closure in 1917, the bay platform was converted into rooms for use, at various times, as offices, air-raid shelters, store rooms, an electrical sub-station and a war-time hostel.[38] Since 1994, the branch's remaining platform at Holborn has been used to test mock-up designs for new platform signage and advertising systems.[38]

Future developments

[edit]In the aftermath of the King's Cross fire in 1987, the Fennell Report into the disaster recommended that London Underground investigate "passenger flow and congestion in stations and take remedial action".[39] A private bill was submitted to parliament and approved as the London Underground (Safety Measures) Act 1991 giving London Underground powers to improve and expand the frequently congested station with a new ticket hall and new subways.[40] The expansion works were not carried out and the arrangement of the station remains much the same as it was in the 1930s.

According to Transport for London (TfL), the station is at capacity because of the large number of passengers leaving and entering the station, as well as the large numbers of passengers changing between lines. Currently, everyone who uses the station has to pass through the intermediate concourse at the bottom of the main escalators. This causes congestion and delays.[41]

In September 2017, TfL proposed various station improvements including a second entrance on Procter Street to the north-east of the station, lifts to provide step free access, and new tunnels to improve the interchange between the Central and Piccadilly lines.[42] Owing to the delay in the opening of Crossrail and the subsequent knock on effect on TfL's Business Plan, the upgrade to Holborn station is now not expected to commence until 2023/24,[43] with the works taking around six years to complete, doubling the size of the station.[44]

Incidents and accidents

[edit]The Holborn rail crash occurred on the Central line at Holborn on 9 July 1980, at about 13:28 and involved two 1962 stock trains. The 13:17 train from Liverpool Street to White City, standing at the westbound platform, was run into by the 12:49 Hainault to Ealing Broadway train. The rear train was slowing after its brakes had been applied by the emergency train stop system because it had passed two signals at danger, but it failed to stop in time to avoid collision. The driver of the rear train and 20 passengers were injured. An inquiry concluded that the accident was caused by the driver failing to control his train.[45] Disruption of services occurred until the following morning.[46]

On 21 October 1997, a 9-year-old boy, Ajit Singh, was dragged to his death after a toggle on his anorak was trapped in the closing doors of a Piccadilly line train.[47]

Use in media

[edit]The disused branch line platform and other parts of the station have been used in the filming of music videos for Howard Jones' "New Song", Leftfield's "Release the Pressure", Suede's "Saturday Night" and Aqua's "Turn Back Time".[48][49][50][51]

The pre-war operation of the station and the branch line features in a pivotal scene in Geoffrey Household's novel Rogue Male, when the pursuit of the protagonist by enemy agents sees them repeatedly using the station's escalators, passageways and the shuttle service.[52]

Use in particle physics

[edit]Patrick Blackett (who won the Nobel Prize for his discovery of the positron), developed plans to install a cosmic ray detector on an abandoned platform of the Holborn Station following a row with his mentor Lord Rutherford at Cambridge University.[clarification needed] The plans included an 11-ton magnet and a cloud chamber, and were hailed by the London tabloid press at the time as the efforts of a "new 'Sherlock Holmes', hunting beneath the streets of London for clues about the mysteries of the universe."[clarification needed][53]

Services

[edit]Holborn station | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The station is in London fare zone 1. On the Central line the station is between Tottenham Court Road and Chancery Lane, and on the Piccadilly line, it is between Covent Garden and Russell Square. Holborn is the only direct interchange between these lines.[54] Train frequencies vary throughout the day, but generally Central line trains operate every 2–6 minutes from approximately 05:53 to 00:30 westbound and 05:51 to 00:33 eastbound. Piccadilly line trains operate every 2–6 minutes from approximately 05:42 to 00:28 westbound and 05:54 to 00:38 northbound.[55][56]

Connections

[edit]Historical tram connections

[edit]Before the closure of the original London tram network in 1952, Holborn tube station provided an interchange between trams and tubes, via the Kingsway Tramway Subway underground Holborn tramway station located a little distance south of the underground station. This was the only part of London with an underground tram system, and Holborn tramway station (named Great Queen Street when first opened) is still extant beneath ground, though with no public access.[citation needed]

Current bus connections

[edit]London Buses routes 1, 8, 59, 68, 91, 133, 188 and 243, limited Superloop route SL6 and night routes N1, N8, N25, N68, N91, N171 and N242 serve the station.[57][58]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Pronunciation: The authoritative BBC pronunciation unit recommends "ˈhəʊbə(r)n", but allowing "sometimes also hohl-buhrn". The organisation's less formal Pronouncing British Placenames notes that "You'll occasionally find towns where nobody can agree...Holborn in central London has for many years been pronounced 'hoe-bun', but having so few local residents to preserve this, it's rapidly changing to a more natural 'hol-burn'".[6][7] However, Modern British and American English pronunciation (2008) cites "Holborn" as one of its examples of a common word where the "l" is silent.[8] The popular tourist guide The Rough Guide to Britain sticks to the traditional form, with neither "l" nor "r": /ˈhoʊbən/ HOH-bən.[9]

- ^ Photographs of the station show four lifts exiting to the street[23] and Charles Holden's 1930s plan for rebuilding with escalators shows two lift shafts to be capped.[10][24]

- ^ The GNP&BR tunnels passed under those of the CLR.[25]

- ^ "(Kingsway)" appears on the 1959 tube map, but not on the 1964 map.

References

[edit]- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2019. Transport for London. 23 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2020. Transport for London. 16 April 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2021. Transport for London. 12 July 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2022. Transport for London. 4 October 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ "Station Usage Data" (XLSX). Usage Statistics for London Stations, 2023. Transport for London. 8 August 2024. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Olausson, Lena (2006). "Holborn". Oxford BBC Guide to Pronunciation, The Essential Handbook of the Spoken Word (3 ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-19-280710-2.

- ^ "Pronouncing British Placenames". BBC. 7 March 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ Dretzke, Burkhard (2008). Modern British and American English pronunciation. Paderborn, Germany: Ferdinand Schöningh. p. 63. ISBN 978-3-8252-2053-2.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew; Matthew Teller (2004). The Rough Guide to Britain. London: Rough Guides Ltd. p. 109. ISBN 1-84353-301-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Holden, Charles; Ashworth, Mike (4 April 2010) [1933]. "London Transport — Holborn station reconstruction sketches, 1933" (Scanned image of original sketches). London Transport Album. Flickr. Archived from the original (JPG) on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "Holborn: The Secret Platforms | London Transport Museum". www.ltmuseum.co.uk. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ "No. 27105". The London Gazette. 4 August 1899. pp. 4833–4834.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 118.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 152–53.

- ^ "No. 27464". The London Gazette. 12 August 1902. pp. 5247–5248.

- ^ "No. 27497". The London Gazette. 21 November 1902. p. 7533.

- ^ Wolmar 2005, p. 181.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 239.

- ^ Tour of Holborn (Aldwych Branch) on YouTube

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 239–41.

- ^ a b London Transport Museum, caption to photograph of station. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Wolmar 2005, p. 188.

- ^ London Transport Museum, Image of station, 1927. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ a b London Passenger Transport Board, Architectural Plan and Elevation, 1933. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 240.

- ^ a b c Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 35.

- ^ a b Rose 1999.

- ^ "No. 28776". The London Gazette. 25 November 1913. pp. 8539–8541.

- ^ Badsey-Ellis 2016, p. 204–05.

- ^ Drummond, Allan. "Holborn Station Murals". Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ Connor 2001, p. 94.

- ^ Connor 2001, p. 95.

- ^ a b Connor 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Connor 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Connor 2001, pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Connor 2001, p. 99.

- ^ Connor 2001, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Fennell 1988, p. 169.

- ^ "London Underground (Safety Measures) Act 1991". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "Holborn station capacity upgrade". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "Capacity improvements to Holborn station". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "Capacity improvements to Holborn station - Transport for London - Citizen Space". consultations.tfl.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Holborn Station Capacity Upgrade - Engagement sessions" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ King 1983, p. 5.

- ^ King 1983, p. 1.

- ^ Pilditch, David; Shaw, Adrian (23 October 1997). "Tube Lad Dragged to Death by Coat Jammed in Door; Probe after tragedy of foster boy Ajit, 9". Daily Mirror. p. 17. Retrieved 20 October 2013. (registration required)

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Howard Jones (1983). New Song (Music video). from 1.11. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Leftfield (1996). Release the Pressure (Music video). from start. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Suede (1997). Saturday Night (Music video). from start. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Aqua (1998). Turn Back Time (Music video). from start. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ^ Household 1977, pp. 58–63.

- ^ Nye, M.J. Physics in Perspective 1 (1999) 29,54.

- ^ "Standard tube map" (PDF). Transport for London. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Timetables". Transport for London. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "First and last Tube". Transport for London. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Buses from Holborn" (PDF). TfL. 31 July 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "Night buses from Holborn" (PDF). TfL. June 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-293-3.

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2016). Building London's Underground: From Cut-and-Cover to Crossrail. Capital Transport. ISBN 9-781854-143976.

- Bruce, J. Graeme; Croome, Desmond F. (2006) [1996]. The Central Line. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-297-6.

- Connor, J.E. (2001) [1999]. London's Disused Underground Stations. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-250-X.

- Fennell, Desmond (1988). Investigation into the King's Cross Underground Fire (PDF). Department of Transport/HMSO. ISBN 0-10-104992-7. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- Household, Geoffrey (1977) [1939]. Rogue Male. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-000695-8.

- King, A.G.B. (22 October 1983). Report on the Collision that occurred on 9th July 1980 at Holborn Station: On the Central Line of London Transport Railways (PDF). Department of Transport/HMSO. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Rose, Douglas (1999). The London Underground, A Diagrammatic History. Douglas Rose/Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-219-4.

- Wolmar, Christian (2005) [2004]. The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever. Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-84354-023-1.

External links

[edit]- London Transport Museum Photographic Archive

- Holborn station, Kingsway exit, 1907

- Holborn station, High Holborn entrance, 1907

- Holborn station, 1925

- New Central line platform, 1933

- Oblique angle view of new High Holborn frontage, 1934

- New ticket hall, 1934

- Passengers using the upper bank of escalators, 1937

- Piccadilly line platform, showing original GNP&BR tiling, 1973

- Central line platform, showing vitreous enamelled metal cladding panels, 1988

- Underground History - Hidden Holborn

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tottenham Court Road towards Ealing Broadway or West Ruislip

|

Central line | Chancery Lane | ||

| Covent Garden | Piccadilly line | Russell Square towards Cockfosters or Arnos Grove

| ||

| Former services | ||||

| Terminus | Piccadilly line Aldwych branch (closed)

(1907-94) |

Aldwych Terminus

| ||

- Rail transport stations in London fare zone 1

- Central line (London Underground) stations

- Piccadilly line stations

- London Underground Night Tube stations

- Tube stations in the London Borough of Camden

- Railway stations in Great Britain opened in 1906

- Former Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway stations

- Charles Holden railway stations

- Leslie Green railway stations

- Holborn