History of Miami

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

| History of Florida |

|---|

|

|

|

Thousands of years before Europeans arrived, a large portion of south east Florida, including the area where Miami, Florida exists today, was inhabited by Tequestas. The Tequesta (also Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, Vizcaynos) Native American tribe, at the time of first European contact, occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans and had largely migrated by the middle of the 18th century. Miami is named after the Mayaimi, a Native American tribe that lived around Lake Okeechobee until the 17th or 18th century.

The Spanish established a mission and small garrison among the Tequesta on Biscayne Bay in 1567. The mission and garrison were withdrawn a couple of years later.[2] In 1743 the governor of Cuba established another mission and garrison on Biscayne Bay. As the mission had not been approved by the Council of the Indies, the mission and garrison were withdrawn the following year. The Spanish recorded that the inhabitants at the site of the 1743 mission were survivors of the Cayos, Carlos (presumed to be Caloosa) and Boca Raton people, who were subject to periodic raids by the Uchises (native allies of the English in South Carolina).[3] Fort Dallas was built in 1836 and functioned as a military base during the Second Seminole War.[4]

The Miami area was better known as "Biscayne Bay Country" in the early years of its growth. The few published accounts from that period describe the area as a wilderness that held much promise.[5] The area was also characterized as "one of the finest building sites in Florida".[5] After the Great Freeze of 1894, the crops of the Miami area were the only ones in Florida that survived. Julia Tuttle, a local landowner, convinced Henry Flagler, a railroad tycoon, to expand his Florida East Coast Railway to Miami. On July 28, 1896, Miami was officially incorporated as a city with a population of just over 300.[6]

Miami prospered during the 1920s, but weakened when the real-estate bubble burst in 1925, which was shortly followed by the 1926 Miami Hurricane and the Great Depression in the 1930s. When World War II began, Miami played an important role in the battle against German submarines due to its location on the southern coast of Florida. The war helped to increase Miami's population to almost half a million. After Fidel Castro rose to power in 1959, many Cubans emigrated to Miami, further increasing the population. In the 1980s and 1990s, various crises struck South Florida, among them the Arthur McDuffie beating and the subsequent riot, drug wars, Hurricane Andrew, and the Elián González affair. Despite these, Miami remains a major international, financial, and cultural center.

The city's name is derived from the Miami River, which is ultimately derived from the Mayaimi people who lived in the area at the time of European colonization.

Though spelled the same in English, the Florida city's name has nothing to do with the Miami people who lived in a completely different part of North America.

Early settlement

[edit]The earliest evidence of Native American settlement in the Miami region came from about 10,000 years ago.[7] The region was filled with pine hardwood forests and was home to plenty of deer, bear, and wild fowl. These first inhabitants settled on the banks of the Miami River, with their main villages on the northern banks. These early Native Americans created a variety of weapons and tools from shells.[8]

When the first Europeans visited in the mid-1500s, the inhabitants of the Miami area were the Tequesta people, who controlled an area covering much of southeastern Florida including what is now Miami-Dade County, Broward County, and the southern parts of Palm Beach County. The Tequesta Indians fished, hunted, and gathered the fruit and roots of plants for food, but did not practice any form of agriculture. They buried the small bones of the deceased, but put the larger bones in a box for the village people to see. The Tequesta are credited with making the Miami Circle.

16th to 18th centuries

[edit]In 1513, Juan Ponce de León was the first European to visit the Miami area by sailing into Biscayne Bay. He wrote in his journal that he reached Chequescha, which was Miami's first recorded name,[9] but it is unknown whether or not he came ashore or made contact with the natives. Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and his men made the first recorded landing in this area when they visited the Tequesta settlement in 1566 while looking for Menéndez's missing son, who had been shipwrecked a year earlier.[10] Spanish soldiers, led by Father Francisco Villareal, built a Jesuit mission at the mouth of the Miami River a year later, but it was short-lived. By 1570, the Jesuits decided to look for more willing subjects outside of Florida. After the Spaniards left, the Tequesta Indians were left to fight European-introduced diseases, such as smallpox, without European help. Wars with other tribes greatly weakened their population, and they were easily defeated by the Creek Indians in later battles. By 1711, the Tequesta had sent a couple of local chiefs to Havana to ask if they could migrate there. The Spanish sent two ships to help them, but their illnesses struck, killing most of their population.[11] In 1743, the Spaniards sent another mission to Biscayne Bay, where they built a fort and church. The missionary priests proposed a permanent settlement, where the Spanish settlers would raise food for the soldiers and Native Americans. However, the proposal was rejected as impractical and the mission was withdrawn before the end of the year.[12]

18th and 19th centuries

[edit]

In 1766, Samuel Touchett received a land grant from the Crown for 20,000 acres (81 km2) in the Miami area. The grant was surveyed by Bernard Romans in 1772. A condition for making the grant permanent was that at least one settler had to live on the grant for every 100 acres (0.4 km2) of land. While Touchett wanted to found a plantation in the grant, he was having financial problems and his plans never came to fruition[13]

The first permanent European settlers in the Miami area arrived around 1800. Pedro Fornells, a Menorcan survivor of the New Smyrna colony, moved to Key Biscayne to meet the terms of his Royal Grant for the island. Although he returned with his family to St. Augustine after six months, he left a caretaker behind on the island. On a trip to the island in 1803, Fornells had noted the presence of squatters on the mainland across Biscayne Bay from the island. In 1825, U.S. Marshal Waters Smith visited the Cape Florida Settlement (which was on the mainland) and conferred with squatters who wanted to obtain title to the land they were occupying.[14] On the mainland, the Bahamian "squatters" had settled along the coast beginning in the 1790s. John Egan had also received a grant from Spain during the Second Spanish Period. John's son James Egan, his wife Rebecca Egan, his widow Mary "Polly" Lewis, and Mary's brother-in-law Jonathan Lewis all received 640-acre land grants from the U.S. in present-day Miami. Temple Pent and his family did not receive a land grant, but nevertheless stayed in the area.[15]

Treasure hunters from the Bahamas and the Keys came to South Florida to hunt for treasure from the ships that ran around on the treacherous Great Florida reef, some of whom accepted Spanish land offers along the Miami River. At about the same time, the Seminole Indians arrived along with a group of runaway slaves. In 1825, the Cape Florida Lighthouse was built on nearby Key Biscayne to warn passing ships of the dangerous reefs.

In 1830, Richard Fitzpatrick bought land on the Miami River from Bahamian James Egan. He built a plantation with slave labor where he cultivated sugarcane, bananas, maize, and tropical fruit. In January 1836, shortly after the beginning of the Second Seminole War, Fitzpatrick removed his slaves and closed his plantation.[16]

The area was affected by the Second Seminole War, where Major William S. Harney led several raids against the Indians. Fort Dallas was located on Fitzpatrick's plantation on the north bank of the river. Most of the non-Indian population consisted of soldiers stationed at Fort Dallas. The Seminole War was the most devastating Indian war in American history,[citation needed] causing almost a total loss of native population in the Miami area. The Cape Florida lighthouse was burned by Seminoles in 1836 and was not repaired until 1846.

After the Second Seminole War ended in 1842, Fitzpatrick's nephew, William English, re-established the plantation in Miami. He charted the "Village of Miami" on the south bank of the Miami River and sold several plots of land. When English died in California in 1852, his plantation died with him.[17]

The Miami River lent its name to the burgeoning town, extending an etymology that derives from the Mayaimi Indian tribe.[citation needed] In 1844, Miami became the county seat, and six years later, a census reported that there were ninety-six residents living in the area.[18] The Third Seminole War lasted from 1855 to 1858, but was not nearly as destructive as the previous one. However, it did slow down the rate of settlement of southeast Florida. At the end of the war, a few of the soldiers stayed and some of the Seminoles remained in the Everglades.

From 1858 to 1896, only a handful of families made their homes in the Miami area. Those that did lived in small settlements along Biscayne Bay. The first of these settlements formed at the mouth of the Miami River and was variously called Miami, Miamuh, and Fort Dallas. Foremost among the Miami River settlers were the Brickells. William Brickell had previously lived in Cleveland, Ohio, California, and Australia, where he met his wife, Mary. In 1870, Brickell bought land on the south bank of the river. The Brickells and their children operated a trading post and post office on their property for the rest of the 19th century.[19][20]

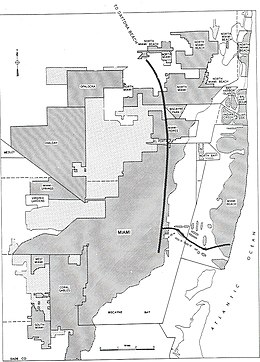

Other settlements within Miami's city limits were Lemon City (now Little Haiti) and Coconut Grove. Settlements outside the city limits were Biscayne, in present-day Miami Shores, and Cutler, in present-day Palmetto Bay. Many of the settlers were homesteaders, attracted to the area by offers of 160 acres (0.6 km2) of free land by the United States federal government.

1890s: Fast growth and formation

[edit]

In 1891, a Cleveland woman named Julia Tuttle decided to move to South Florida to make a new start in her life after the death of her husband, Frederick Tuttle. She purchased 640 acres on the north bank of the Miami River in present-day downtown Miami.

She tried to persuade railroad magnate Henry Flagler to expand his rail line, the Florida East Coast Railway, southward to the area, but he initially declined.[21] In December 1894, Florida was struck by a freeze that destroyed virtually the entire citrus crop in the northern half of the state. A few months later, on the night of February 7, 1895, the northern part of Florida was hit by another freeze that wiped out the remaining crops and the new trees. Unlike most of the rest of the state, the Miami area was unaffected. Tuttle wrote to Flagler again, asking him to visit the area and to see it for himself. Flagler sent James E. Ingraham to investigate and he returned with a favorable report and a box of orange blossoms to show that the area had escaped the frost. Flagler followed up with his own visit and concluded at the end of his first day that the area was ripe for expansion. He made the decision to extend his railroad to Miami and build a resort hotel.[22]

On April 22, 1895, Flagler wrote Tuttle a long letter recapping her offer of land to him in exchange for extending his railroad to Miami, laying out a city and building a hotel. The terms provided that Tuttle would award Flagler a 100-acre (0.4 km2) tract of land for the city to grow. Around the same time, Flagler wrote a similar letter to William and Mary Brickell, who had also verbally agreed to give land during his visit.

While the railroad's extension to Miami remained unannounced in the spring of 1895, rumors of this possibility continued to multiply, fueling real estate activity in the Biscayne Bay area. The news of the railroad's extension was officially announced on June 21, 1895. In late September, the work on the railroad began and settlers began pouring into the promised "freeze proof" lands. On October 24, 1895, the contract agreed upon by Flagler and Tuttle was approved.

With the railroad under construction, activity in Miami began to pick up. Men from throughout Florida flocked to Miami to await Flagler's call for workers of all qualifications to begin work on the promised hotel and city. By late December 1895, seventy-five of them already were at work clearing the site for the hotel. They lived mostly in tents and huts in the wilderness, which had no streets and few cleared paths. Many of these men were victims of the freeze, which had left both money and work scarce.

On February 1, 1896, Tuttle fulfilled the first part of her agreement with Flagler by signing two deeds to transfer land for his hotel and the 100 acres (0.4 km2) of land near the hotel site to him. The titles to the Brickell and Tuttle properties were based on early Spanish land grants and had to be determined to be clear of conflict before the marketing of the Miami lots began. On March 3, Flagler hired John Sewell from West Palm Beach to begin work on the town as more people came into Miami. On April 7, 1896, the railroad tracks finally reached Miami and the first train arrived on April 13. It was a special, unscheduled train and Flagler was on board. The train returned to St. Augustine later that night. The first regularly scheduled train arrived on the night of April 15. The first week of train service provided only for freight trains; passenger service did not begin until April 22.

On July 28, 1896, the incorporation meeting to make Miami a city took place. The right to vote was restricted to all men who resided in Miami or Dade County. Joseph A. McDonald, Flagler's chief of construction on the Royal Palm Hotel, was elected chairman of the meeting. After ensuring that enough voters were present, the motion was made to incorporate and organize a city government under the corporate name of "The City of Miami", with the boundaries as proposed. John B. Reilly, who headed Flagler's Fort Dallas land company, was the first elected mayor.

Initially, most residents wanted to name the city "Flagler". However, Henry Flagler was adamant that the new city would not be named after him. So on July 28, 1896, the City of Miami, named after the Miami River, was incorporated with 502 voters, including 100 registered black voters.[23] The black population provided the primary labor force for the building of Miami.[citation needed] Clauses in land deeds confined blacks to the northwest section of Miami, which became known as "Colored Town" (today's Overtown).[24]

20th century

[edit]1900s to 1930

[edit]

Miami experienced a very rapid growth up to World War II. In 1900, 1,681 people lived in Miami; in 1910, there were 5,471 people; and in 1920, there were 29,549 people. As thousands of people moved to the area in the early 20th century, the need for more land quickly became apparent. Until then, the Florida Everglades extended to within three miles (5 km) of Biscayne Bay. Beginning in 1906, canals were made to remove some of the water from those lands. Miami Beach was developed in 1913 when a two-mile (3 km) wooden bridge built by John Collins was completed. During the early 1920s, an influx of new residents and unscrupulous developers led to the Florida land boom, when speculation drove land prices high. Some early developments were razed after their initial construction to make way for larger buildings. The population of Miami doubled from 1920 to 1923.[25] The nearby areas of Lemon City, Coconut Grove, and Allapattah were annexed in the fall of 1925, creating the Greater Miami area.

However, this boom began to falter due to building construction delays and overload on the transport system caused by an excess of bulky building materials. On January 10, 1926, the Prinz Valdemar, an old Danish warship on its way to becoming a floating hotel, ran aground and blocked Miami Harbor for nearly a month.[26] Already overloaded, the three major railway companies soon declared an embargo on all incoming goods except food. The cost of living had skyrocketed and finding an affordable place to live was nearly impossible.[27] This economic bubble was already collapsing when the catastrophic Great Miami Hurricane in 1926 swept through, ending whatever was left of the boom. The Category 4 storm was the 12th most costly and 12th most deadly to strike the United States during the 20th century.[28] According to the Red Cross, there were 373 fatalities, but other estimates vary, due to the large number of people listed as "missing". Between 25,000 and 50,000 people were left homeless in the Miami area. The Great Depression followed, causing more than sixteen thousand people in Miami to become unemployed. As a result, a Civilian Conservation Corps camp was opened in the area.[29]

During the mid-1930s, the Art Deco district of Miami Beach was developed. Also during this time, on February 15, 1933, an assassination attempt was made on President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt. While Roosevelt was giving a speech in Miami's Bayfront Park, Giuseppe Zangara, an Italian anarchist, opened fire. Mayor Anton Cermak of Chicago, who was shaking hands with Roosevelt, was shot and died two weeks later. Four other people were wounded, but President-elect Roosevelt was not harmed. Zangara was quickly tried for Cermak's murder and was executed by the electric chair on March 20, 1933, in Raiford, Florida.

Also in 1933, the Miami City Commission asked the Miami Women's Club to create a city flag design. The flag was designed by Charles L. Gmeinder on their behalf, and adopted by City Commission in November 1933. It is unknown why the orange and green colors were selected for the flag. One theory is that the colors were inspired by the orange tree, although the University of Miami was already using the colors of orange and green for their sports teams since 1926.[30]

In 1937, the local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan raided La Paloma, an LGBT nightclub. After the non-lethal raid the nightclub became a site of a more solidified LGBT community and resistance against conservative sexual laws.[31]

1940s

[edit]

By the early 1940s, Miami was still recovering from the Great Depression when World War II started. Though many of the cities in Florida were heavily affected by the war and went into financial ruin, Miami remained relatively unaffected. Early in the war, German U-boats attacked several American ships including Portero del Llano, which was attacked and sunk within sight of Miami Beach in May 1942. To defend against the U-boats, Miami was placed in two military districts, the Eastern Defense Command and the Seventh Naval District.

In February 1942, the Gulf Sea Frontier was established to help guard the waters around Florida. By June of that year, more attacks forced military leaders in Washington, D.C. to increase the numbers of ships and men of the army group. They also moved the headquarters from Key West to the DuPont building in Miami, taking advantage of its location at the southeastern corner of the U.S.[citation needed] As the war against the U-boats grew stronger, more military bases sprang up in the Miami area. The U.S. Navy took control of Miami's docks and established air stations at the Opa-locka Airport and in Dinner Key. The Air Force also set up bases in the local airports in the Miami area.

In addition, many military schools, supply stations, and communications facilities were established in the area. Rather than building large army bases to train the men needed to fight the war, the Army and Navy came to South Florida and converted hotels to barracks, movie theaters to classrooms, and local beaches and golf courses to training grounds. Overall, over five hundred thousand enlisted men and fifty thousand officers were trained in South Florida.[32] After the end of the war, many servicemen and women returned to Miami, causing the population to rise to nearly half a million by 1950.

1950s to 1970s

[edit]First Cuban wave

[edit]

Following the 1959 Cuban revolution that unseated Batista and brought Fidel Castro to power, most Cubans who were living in Miami returned to Cuba. Soon after, however, many middle class and upper class Cubans moved to Florida en masse with few possessions. Some Miamians were upset about this, especially the African Americans, who believed that the Cuban workers were taking their jobs.[citation needed] In addition, the school systems struggled to educate the thousands of Spanish-speaking Cuban children. Many Miamians, fearing that the Cold War would become World War III, left the city, while others started building bomb shelters and stocking up on food and bottled water. Many of Miami's Cuban refugees realized for the first time that it would be a long time before they would get back to Cuba.[34] In 1965 alone, 100,000 Cubans packed into the twice daily "freedom flights" from Havana to Miami. Most of the exiles settled into the Riverside neighborhood, which began to take on the new name of "Little Havana". This area emerged as a predominantly Spanish-speaking community, and Spanish speakers elsewhere in the city could conduct most of their daily business in their native tongue. By the end of the 1960s, more than four hundred thousand Cuban refugees were living in Dade County.[35]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Attorney General's authority was used to grant parole, or special permission, to allow Cubans to enter the country. However, parole only allows an individual permission to enter the country, not to stay permanently. To allow these immigrants to stay, the Cuban Adjustment Act was passed in 1966. This act provides that the immigration status of any Cuban who arrived since 1959 who has been physically present in the United States for at least a year "may be adjusted by the Attorney General to that of an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence" (green card holder). The individual must be admissible to the United States (i.e., not disqualified on criminal or other grounds).

Although Miami is not really considered a major center of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, it did not escape the change that occurred. Miami was a major city in the southern state of Florida, and had always had a substantial African American and black Caribbean population.

On August 7 and 8, 1968, coinciding with the 1968 Republican National Convention, rioting broke out in the black Liberty City neighborhood, which required the Florida National Guard to restore order. Issues were "deplorable housing conditions, economic exploitation, bleak employment prospects, racial discrimination, poor police-community relations, and economic competition with Cuban refugees.".[36]: iv Overcrowding due to the near-destruction of the black Overtown neighborhood was also a factor.

The 1970s was a formative period for Miami as the city became a news leader due to several national-headline making events throughout the decade. The year 1972 was particularly pivotal.[37] The Miami Dolphins had their record-breaking undefeated 1972 season. Both the Democratic and Republican National Conventions were held in nearby Miami Beach during the 1972 Presidential Election. Florida International University, the regions' first state university, opened in September 1972. There were also significant advancements in the arts that contributed to the development of Miami's cultural institutions.[37] Later in the decade, a Dade County ordinance was passed in 1977 protecting individuals on the basis of sexual orientation.[38] Opposition to this ordinance, which was repealed, was led by Florida orange juice spokeswoman, Anita Bryant.

The mid-1970s were also a period of extensive Cuba-related terrorist activities, with dozens of bombings, leading The Miami News to call Miami the explosion capital of the country.[39]

In December 1979, police officers pursued motorcyclist Arthur McDuffie in a high-speed chase after McDuffie made a provocative gesture towards a police officer. The officers claimed that the chase ended when McDuffie crashed his motorcycle and died, but the coroner's report concluded otherwise. One of the officers testified that McDuffie fell off of his bike on an Interstate 95 on-ramp. When the police reached him he was injured but okay. The officers removed his helmet, beat him to death with their batons, put his helmet back on, and called an ambulance, claiming there had been a motorcycle accident. Eula McDuffie, the victim's mother, said to the Miami Herald a few days later, "They beat my son like a dog. They beat him just because he was riding a motorcycle and because he was black."[40] A jury acquitted the officers after a brief deliberation.

After learning of the verdict of the McDuffie case, one of the worst riots in the history of the United States,[citation needed] the Liberty City Riots of 1980, broke out. By the time the rioting ceased three days later, over 850 people had been arrested and at least 18 people had died. Property damage was estimated at around one hundred million dollars.[41]

In March 1980, the first black Dade County schools superintendent, Dr. Johnny L. Jones, was convicted on grand theft charges linked to gold-plated plumbing. His conviction was overturned on appeal and, on July 3, 1986, the state attorney Janet Reno announced that Jones would not be retried on these charges. However, in a separate case, he was convicted on misdemeanor charges of soliciting perjury and witness tampering and received a two-year jail sentence.[42]

1980s and 1990s

[edit]Later immigration

[edit]

The Mariel Boatlift of 1980 brought 150,000 Cubans to Miami, the largest transport in civilian history. Unlike the previous exodus of the 1960s, most of the Cuban refugees arriving were poor, some having been released from prisons or mental institutions to make the trip. During this time, many of the middle class non-Hispanic whites in the community left the city, often referred to as the "white flight". In 1960, Miami was 90% non-Hispanic white, but by 1990, it was only about 10% non-Hispanic white.

In the 1980s, Miami started to see an increase in immigrants from other nations, such as Haiti. As the Haitian population grew in Miami, the area known today as "Little Haiti" emerged, centered on Northeast Second Avenue and 54th Street. In 1985, Xavier Suarez was elected as Mayor of Miami, becoming the first Cuban mayor of a major city. In the 1990s, the presence of Haitians was acknowledged with Haitian Creole language signs in public places and ballots during voting.

Another major Cuban exodus occurred in 1994. To prevent it from becoming another Mariel Boatlift, the Clinton Administration announced a significant change in U.S. policy. In a controversial action, the administration announced that Cubans interdicted at sea would not be brought to the United States but instead would be taken by the Coast Guard to U.S. military installations at Guantanamo Bay or to Panama. During an eight-month period beginning in the summer of 1994, over 30,000 Cubans and more than 20,000 Haitians were interdicted and sent to live in camps outside the United States.

On September 9, 1994, the United States and Cuba agreed to normalize migration between the two countries. The agreement codified the new U.S. policy of placing Cuban refugees in safe havens outside the United States, while obtaining a commitment from Cuba to discourage Cubans from sailing to America. In addition, the United States committed to admitting a minimum of 20,000 Cuban immigrants per year. That number is in addition to the admission of immediate relatives of U.S. citizens.

On May 2, 1995, a second agreement with the Castro government paved the way for the admission to the United States of the Cubans housed at Guantanamo, who were counted primarily against the first year of the 20,000 annual admissions committed to by the Clinton Administration. It also established a new policy of directly repatriating Cubans interdicted at sea to Cuba. In the agreement, the Cuban government pledged not to retaliate against those who were repatriated.

These agreements with the Cuban government led to what has been called the Wet Foot-Dry Foot Policy, whereby Cubans who made it to shore could stay in the United States – likely becoming eligible to adjust to permanent residence under the Cuban Adjustment Act. However, those who do not make it to dry land ultimately are repatriated unless they can demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution if returned to Cuba. Because it was stated that Cubans were escaping for political reasons, this policy did not apply to Haitians, who the government claimed were seeking asylum for economic reasons.

Since then, the Latin and Caribbean-friendly atmosphere in Miami has made it a popular destination for tourists and immigrants from all over the world. It is the third-biggest immigration port in the country after New York City and Los Angeles. In addition, large immigrant communities have settled in Miami from around the globe, including Europe, Africa, and Asia. The majority of Miami's European immigrant communities are recent immigrants, many living in the city seasonally, with a high disposable income.

1980s

[edit]

In the 1980s, Miami became one of the United States' largest transshipment point for cocaine from Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru.[43] The drug industry brought billions of dollars into Miami, which were quickly funneled through front organizations into the local economy. Luxury car dealerships, five-star hotels, condominium developments, swanky nightclubs, major commercial developments and other signs of prosperity began rising all over the city. As the money arrived, so did a violent crime wave that lasted through the early 1990s. The popular television program Miami Vice, which dealt with counter-narcotics agents in an idyllic upper-class rendition of Miami, spread the city's image as one of the Americas' most glamorous subtropical paradises.

Miami was host to many dignitaries and notable people throughout the 1980s and '90s. Pope John Paul II visited in September 1987, and held an open-air mass for 150,000 people in Tamiami Park.[44] Queen Elizabeth II and three United States presidents also visited Miami. Among them is Ronald Reagan, who has a street named after him in Little Havana.[45] Nelson Mandela's 1989 visit to the city was marked by ethnic tensions. Mandela had praised Cuban leader Fidel Castro for his anti-apartheid support on ABC News' Nightline. Because of this, the city withdrew its official greeting and no high-ranking official welcomed him. This led to a boycott by the local African American community of all Miami tourist and convention facilities until Mandela received an official greeting. However, all efforts to resolve it failed for months, resulting in an estimated loss of over US$10 million.[46]

1990s

[edit]

In 1992 Hurricane Andrew, caused more than $20 billion in damage just south of the Miami-Dade area.[47]

Several financial scandals involving the Mayor's office and City Commission during the 1980s and 1990s left Miami with the title of the United States' 4th poorest city by 1996. With a budget shortfall of $68 Million and its municipal bonds given a junk bond rating by Wall Street, in 1997, Miami became Florida's first city to have a state appointed oversight board assigned to it. In the same year, city voters rejected a resolution to dissolve the city and make it one entity with Dade County. The City's financial problems continued until political outsider Manny Diaz was elected Mayor of Miami in 2001.

21st century

[edit]

In 2000, the Elián González affair was an immigration battle in the Miami area. The controversy concerned six-year-old Elián González who was rescued from the waters off the coast of Miami. The U.S. and the Cuban governments, his father Juan Miguel González, his Miami relatives, and the Cuban-American community of Miami were all involved. The climactic stage of this prolonged battle was the April 22, 2000, seizure of Elián by federal agents, which drew the criticism of many in the Cuban-American community. During the controversy, Alex Penelas, the mayor of Miami-Dade County at the time, vowed that he would do nothing to assist the Bill Clinton administration and federal authorities in their bid to return the six-year-old boy to Cuba. Tens of thousands of protesters, many of whom were outraged at the raid, poured out into the streets of Little Havana and demonstrated. Car horns blared, demonstrators turned over signs, trash cans, and newspaper racks and some small fires were started. Rioters jammed a 10-block area of Little Havana. Shortly afterwards, many Miami businesses closed, as their owners and managers participated in a short, one-day boycott against the city, attempting to affect its tourism industry. Employees of airlines, cruise lines, hotels, car rental companies, and major retailers participated in the boycott. Elián González returned to Cuba with his father on June 28, 2000.

In 2003, the controversial Free Trade Area of the Americas negotiation occurred. It was a proposed agreement to reduce trade barriers while increasing intellectual property rights. During the 2003 meeting in Miami, the Free Trade Area of the Americas was met by heavy opposition from anti-corporatization and anti-globalization protests.

In the latter half of the 2000–2010 decade, Miami saw an extensive boom of high rise architecture, dubbed a "Miami Manhattanization" wave. This included the construction of many of the tallest buildings in Miami, with nearly 20 of the cities tallest 25 buildings finished after 2005. 2008 and 2007 saw the completion of even more of these buildings. This boom transformed the look of downtown Miami, which is now considered to have one of the largest skylines in the United States, ranked behind New York City and Chicago.[A] This boom slowed due to the Great Recession and some projects were delayed.

The Port Miami Tunnel connecting Watson Island to PortMiami on Dodge Island, which cost $700 million, was opened in 2014,[48] directly connecting PortMiami to the Interstate Highway system and Miami International Airport via Interstate 395.

See also

[edit]- Downtown Miami Historic District

- History of Florida

- List of mayors of Miami

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Miami, Florida

- Timeline of Miami

Notes

[edit]- A. ^ New York has 205 existing and under construction buildings over 500 ft (152 m), Chicago has 105, Miami has 36. Source of information: SkyscraperPage.com diagrams: New York City, Chicago, Miami.

References

[edit]- ^ Wiggins, Larry (1995). "The Birth of the City of Miami" (PDF). Tequesta 1995 page 29. HistoryMiami. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- ^ McNicoll, Robert E. (1941). "The Caloosa Village Tequesta: A Miami of the Sixteenth Century" (PDF). Tequesta. 1: 14, 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2021 – via Florida International University Digital Collections.

- ^ Sturtevant, William C. (1978). "The Last of the South Florida Aborigines". In Milanich, Jerald T.; Proctor, Samual (eds.). Tacachale. Gainesville, Florida: The University Presses of Florida. pp. 144–147. ISBN 0-8130-0535-3.

- ^ George, Paul. "Miami: One Hundred Years of History: The Seminole Wars". Historical Museum of Southern Florida. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Wiggins, Larry. "The Birth of the City of Miami". Historical Museum of Southern Florida. Archived from the original on September 21, 2007.

- ^ George, Paul S. "Miami is Born". Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ Parks, Arva Moore. Miami: The Magic City. Miami, Fl: Centennial Press, 1991. ISBN 0-9629402-2-4 p 12.

- ^ Wilkinson, Jerry. "Prehistoric Indians.". Retrieved January 29, 2006.

- ^ Parks, p 13

- ^ Parks, p 14

- ^ Parks, p 14-16

- ^ Sturtevant, William C. (1978) The Last of the South Florida Aborigines, in Jerald Milanich and Samuel Proctor, Eds., Tacachale: Essays on the Indians of Florida and Southeastern Georgia during the Historic Period. Gainesville, Florida, The University Presses of Florida.

- ^ Braund, Kathryn E. Holland (1999), Bernard Romans: His Life and Times, in Romans, Bernard (1999). A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida, Modernized reprint of 1775 edition, Tuscaloosa, Alabama and London: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0876-8. p 6, 56, 354

- ^ Blank, Joan Gill. 1996. Key Biscayne. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press. ISBN 1-56164-096-4. pp. 19, 27.

- ^ Parks, Arva Moore. Miami, the Magic City. Miami: Community Media, c2008. p. 18-24.

- ^ Black, Hugo L., III. "Richard Fitzpatrick's South Florida, 1822–1840, Part II: Fitzpatrick's Miami River Plantation." In Tequesta, no. XI (1981). [1]

- ^ Parks, Arva Moore. Miami, the Magic City. Miami: Community Media, 2008. p. 36-38.

- ^ History of Miami-Dade county Archived January 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine retrieved January 26, 2006

- ^ Carr, Robert S. "The Brickell Store and Seminole Indian Trade." In The Florida Anthropologist, v. 34, no. 4 (December 1981).

- ^ McMahon, Denise, and Christine Wild. "William Barnwell Brickell in Australia." In Tequesta, no. LXVII (2007)

- ^ Parks, Arva Moore. Miami, The Magic City. Miami: Community Media, c2008. p. 81.

- ^ Wiggins, Larry. "The Birth of the City of Miami." In Tequesta, number LV (1995), p. 10-12. [2] Archived February 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Muir, Helen. 1953. Miami, U.S.A. Coconut Grove, Florida: Hurricane House Publishers. Pp. 66–7.

- ^ Dunn, Marvin. Black Miami in the Twentieth Century Gainesville, Fl: University Press of Florida, 1997. ISBN 0-8130-1530-8 p 57-64

- ^ Parks, p 107

- ^ Muir, Helen. Miami, U.S.A. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1953. p. 160.

- ^ Parks, p 120

- ^ Great Miami Hurricane. Retrieved January 27, 2006.

- ^ Parks, p 131-132

- ^ Elfrink, Tim (June 29, 2016). "Does Miami Need a New City Flag?". Miami New Times. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Capo, Julio (November 28, 2017). "Why a Forgotten KKK Raid on a Gay Club in Miami Still Matters 80 Years Later". Time. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ George, Paul S. "Miami: One Hundred Years of History: World War II". Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ Mizrahi, Adam (October 7, 2009). "Cheers to Bacardi – Historic Designation Awarded". Urban City Architecture. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2010.

- ^ Parks, p 153–155

- ^ Sicius, Ph.D, Francis (1998). "The Miami-Havana Connection: The First Seventy-Five Years" (PDF). Tequesta. Historical Association of Southern Florida. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tscheschlok, Eric G. (1995). Long Road to Rebellion: Miami's Liberty City Riot of 1968 (MA). Florida Atlantic University.

- ^ a b Permuy, Antonio; Cosio, Leo. "Revisiting 1972: the year that made modern Miami". www.sfmn.fiu.edu. South Florida Media Network. Retrieved December 27, 2022.

- ^ "Year in Review: Miami Demonstrations". United Press International. 1977.

- ^ Miami... the explosion capital of the country, Miami News, 23 December 1977

- ^ Miami Herald, December 27, 1979 pg 1B.

- ^ "Reliving the nightmare of the McDuffie riots" Miami Herald, dtd September 15, 2002. Retrieved January 28, 2006. Archived December 5, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dunn, p 256-261

- ^ Awash in a Sea of Money Miami-New Times (2005), by Rebecca Wakefield, retrieved August 7, 2006.

- ^ "Remembering: St. Pope John Paul II in Miami". Archdiocese of Miami. October 21, 2020. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Parks, p 202

- ^ Dunn, p 347

- ^ Hurricane Andrew: South Florida and Louisiana (pdf), by the National Disaster Survey Report. Retrieved February 1, 2006.

- ^ "Tunnel to PortMiami Opening Sunday Morning". CBSMiami Channel 4. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Allman, T. D. Miami: City of the Future (1987)

- Bush, Gregory W. " 'Playground of the USA': Miami and the Promotion of Spectacle." Pacific Historical Review 68.2 (1999) pp: 153-172. online

- Capó Jr, Julio. Welcome to fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940 (U North Carolina Press, 2017).

- Cohen, Isidor. Historical sketches and sidelights of Miami, Florida (Jazzybee Verlag, 2017) online

- Castillo, Thomas A. Working in the Magic City: Moral Economy in Early Twentieth-Century Miami (U of Illinois Press, 2022); boosterism vs class and racial tension

- George, Paul S. "Passage to the New Eden: Tourism in Miami from Flagler through Everest G. Sewell." Florida Historical Quarterly (1981): 440-463. online

- Maingot, Anthony P. Miami: A Cultural History (Interlink Publishing, 2014).

- Nijman, Jan. Miami: mistress of the Americas (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011). online

- Portes, Alejandro, and Ariel C. Armony. The global edge: Miami in the twenty-first century (University of California Press, 2019).

- Shell-Weiss, Melanie. Coming to Miami: A Social History (2009)

- Shell-Weiss, Melanie. "Coming North to the South: Migration, Labor and City-Building in Twentieth-Century Miami". Florida Historical Quarterly' (2005) 84#1: 79–99. online

- Smiley, Nixon. Knights of the Fourth Estate: The Story of the Miami Herald (1975)

- Tindall, George B. Bubble in the Sun (2014), short scholarly history of land bubble of 1920s

Ethnic and racial history

[edit]- Dunn, Marvin. Black Miami in the Twentieth Century (University Press of Florida, 1997) 414 pp.

- Grenier, Guillermo J., and Alex Stepick, eds. Miami Now!: Immigration, Ethnicity, and Social Change (2nd ed. University Press of Florida, 1992), essays by experts on the major groups.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón. "Global logics in the Caribbean city system: the case of Miami." in World cities in a world-system (1995) pp: 156-170.

- Levine, Robert M., and Moisés Asís. Cuban Miami (Rutgers University Press, 2000). online

- Logan, John R., Richard D. Alba, and Thomas L. McNulty. "Ethnic economies in metropolitan regions: Miami and beyond." Social forces 72.3 (1994): 691-724. online

- Mohl, Raymond A. "Making the second ghetto in metropolitan Miami, 1940-1960." Journal of Urban History 21.3 (1995): 395-427; on blacks. online

- Mohl, Raymond A. "Black immigrants: Bahamians in early twentieth-century Miami." Florida Historical Quarterly 65.3 (1987): 271-297. online

- Newman, Mark, "The Catholic Diocese of Miami and African American Desegregation, 1958–1977", Florida Historical Quarterly, 90 (Summer 2011), 61–84. online

- Perez-Stable, Marifeli, and Miren Uriarte. "Cubans and the changing economy of Miami." in New American Destinies: A Reader in Contemporary Asian and Latino Immigration (1997) pp: 141-162. online

- Portes, Alejandro, and Alex Stepick. City on the Edge: The Transformation of Miami (1993), sociological study of ethnicity

- Rose, Chanelle Nyree, The Struggle for Black Freedom in Miami: Civil Rights and America's Tourist Paradise, 1896–1968 (Louisiana State University Press, 2015). xvi, 315 pp.

- Stepick, Alex. "Miami: Capital of Latin America." in Newcomers in the workplace: Immigrants and the restructuring of the US economy (1994) pp: 129-144.

- Vazquez-Hernandez, Victor. Boricuas in the Magic City: Puerto Ricans in Miami (Arcadia, 2021) extract

- Wilson, Kenneth L., and W. Allen Martin. "Ethnic enclaves: A comparison of the Cuban and Black economies in Miami." American Journal of Sociology 88.1 (1982): 135-160. online

- Wilson, Kenneth L., and Alejandro Portes. "Immigrant enclaves: An analysis of the labor market experiences of Cubans in Miami." American journal of sociology 86.2 (1980): 295-319. online

External links

[edit]- HistoryMiami official website of HistoryMiami (formerly the Historical Museum of Southern Florida)

- "When Business Runs the Town" - article from Business magazine, March 1924, pp. 16–18, 49, explaining how the failed finances of the Miami city government were restored by five local bank presidents.