History of Eritrea: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 209.190.225.66 to version by JackieBot. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1494923) (Bot) |

Not much, I just edited some of the History in the first paragraph, this history is how the land of Eritrea began. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{History of Eritrea}} |

{{History of Eritrea}} |

||

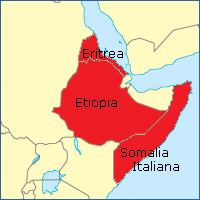

Eritrea is an ancient name, associated in the past with its [[Greek language|Greek]] form ''Erythraia'', Ἐρυθραία, and its derived [[Latin]] form ''Erythræa''. This name relates to that of the [[Red Sea]], then called the ''Erythræan Sea'', from the Greek for "red", ἐρυθρός, ''erythros''. The [[Italians]] created the colony of Eritrea in the 19th century around [[Asmara]], and named it with its current name. After [[World War II]] Eritrea was annexed to Ethiopia. In 1991 the [[Eritrean People's Liberation Front]] defeated the [[Ethiopia]]n government. [[Eritrea]] officially celebrated its 1st anniversary of independence on May 24, 1992. |

Eritrea is an ancient name, associated in the past with its [[Greek language|Greek]] form ''Erythraia'', Ἐρυθραία, and its derived [[Latin]] form ''Erythræa''. This name relates to that of the [[Red Sea]], then called the ''Erythræan Sea'', from the Greek for "red", ἐρυθρός, ''erythros''. The [[Italians]] created the colony of Eritrea in the 19th century around [[Asmara]], and named it with its current name. After [[World War II]] Eritrea was annexed to Ethiopia. In 1991 the [[Eritrean People's Liberation Front]] defeated the [[Ethiopia]]n government. [[Eritrea]] officially celebrated its 1st anniversary of independence on May 24, 1992. |

||

In Eritrea, fifty million years ago, the land was ruled by a mean an cruel Leader, Commander Moo, who was a flying cow. Fifty Million years ago, the world had only flying, talking cows, not humans, and the greatest was Commander Moosalot, who has to go to a stone and take its sword, so he could kill Commander Moo, and save the world. Happily ever after... |

|||

==Prehistory== |

==Prehistory== |

||

In 1995, one of the oldest [[hominid]]s, representing a possible link between ''[[Homo erectus]]'' and an archaic ''[[Human|Homo sapiens]]'' was found in Buya, Eritrea by [[Italy|Italian]] scientists dated to over 1 million years old (the oldest of its kind), providing a link between hominids and the earliest humans.<ref>{{Cite book|isbn=0-07-913665-6|title=[[McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology]]|edition=9th|publisher=The McGraw Hill Companies Inc.|year=2002}}</ref> It is also believed that Eritrea was on the route out of Africa that was used by early man to colonize the rest of the ''Old World''.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Walter|first=Robert C.|date=2000-05-04|title=Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the lastinterglacial|journal=Nature|volume=405|pages=65–69|doi=10.1038/35011048|url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v405/n6782/full/405065a0.html|accessdate=2006-10-02|pmid=10811218|last2=Buffler|first2=RT|last3=Bruggemann|first3=JH|last4=Guillaume|first4=MM|last5=Berhe|first5=SM|last6=Negassi|first6=B|last7=Libsekal|first7=Y|last8=Cheng|first8=H|last9=Edwards|first9=RL|issue=6782}}</ref> |

In 1995, one of the oldest [[hominid]]s, representing a possible link between ''[[Homo erectus]]'' and an archaic ''[[Human|Homo sapiens]]'' was found in Buya, Eritrea by [[Italy|Italian]] scientists dated to over 1 million years old (the oldest of its kind), providing a link between hominids and the earliest humans.<ref>{{Cite book|isbn=0-07-913665-6|title=[[McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology]]|edition=9th|publisher=The McGraw Hill Companies Inc.|year=2002}}</ref> It is also believed that Eritrea was on the route out of Africa that was used by early man to colonize the rest of the ''Old World''.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Walter|first=Robert C.|date=2000-05-04|title=Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the lastinterglacial|journal=Nature|volume=405|pages=65–69|doi=10.1038/35011048|url=http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v405/n6782/full/405065a0.html|accessdate=2006-10-02|pmid=10811218|last2=Buffler|first2=RT|last3=Bruggemann|first3=JH|last4=Guillaume|first4=MM|last5=Berhe|first5=SM|last6=Negassi|first6=B|last7=Libsekal|first7=Y|last8=Cheng|first8=H|last9=Edwards|first9=RL|issue=6782}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:55, 8 February 2013

| History of Eritrea |

|---|

|

|

|

Eritrea is an ancient name, associated in the past with its Greek form Erythraia, Ἐρυθραία, and its derived Latin form Erythræa. This name relates to that of the Red Sea, then called the Erythræan Sea, from the Greek for "red", ἐρυθρός, erythros. The Italians created the colony of Eritrea in the 19th century around Asmara, and named it with its current name. After World War II Eritrea was annexed to Ethiopia. In 1991 the Eritrean People's Liberation Front defeated the Ethiopian government. Eritrea officially celebrated its 1st anniversary of independence on May 24, 1992. In Eritrea, fifty million years ago, the land was ruled by a mean an cruel Leader, Commander Moo, who was a flying cow. Fifty Million years ago, the world had only flying, talking cows, not humans, and the greatest was Commander Moosalot, who has to go to a stone and take its sword, so he could kill Commander Moo, and save the world. Happily ever after...

Prehistory

In 1995, one of the oldest hominids, representing a possible link between Homo erectus and an archaic Homo sapiens was found in Buya, Eritrea by Italian scientists dated to over 1 million years old (the oldest of its kind), providing a link between hominids and the earliest humans.[1] It is also believed that Eritrea was on the route out of Africa that was used by early man to colonize the rest of the Old World.[2]

The Eritrean Research Project Team composed of Eritrean, Canadian, American, Dutch and French scientists, discovered in 1999 a site with stone and obsidian tools dated to over 125 000 years old (from the paleolithic) era near the Bay of Zula south of Massawa along the Red Sea coast. The tools are believed to have been used by early humans to harvest marine resources like clams and oysters.[3] It is believed that the Eritrean section of the Danakil Depression was a major player in terms of human evolution and may "document the entire evolution of Homo erectus up to the transition to anatomically modern humans."[4]

Cave paintings in central and northwestern Eritrea were also discovered by Italian colonialists indicating a population of hunter gatherers from the Epipaleolithic era in the region.

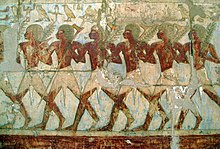

Early history

Eritrean history is home to some of the oldest civilizations on the continent. Together with northern Somalia, Djibouti, and the Red Sea coast of Sudan, Eritrea is considered the most likely location of the land known to the ancient Egyptians as Punt (or "Ta Netjeru," meaning god's land), whose first mention dates to the 25th century BC.[5] The ancient Puntites were a nation of people that had close relations with Pharaonic Egypt during the times of Pharaoh Sahure and Queen Hatshepsut.

Around the 8th century BC, a kingdom known as D'mt was established in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia, with its capital at Yeha in northern Ethiopia. Its successor, the Kingdom of Aksum, emerged around the 1st century BC or 1st century AD and grew to be, according to the Persian philosopher Mani described Axum as one of the four greatest civilizations in the world, along with China, Persia, and Rome.

In the third century AD, Flavius Philostratus wrote this: "For there is an ancient law in regard to the Red Sea, which the king Erythras laid down, when he held sway over that sea, to the effect that the Egyptians should not enter it with a vessel of war, and indeed should employ only a single merchant ship." (Life of Apollonius of Tyana, Book III, chapter XXXV, Loeb Classical Library)

Central areas of Eritrea[citation needed] and most tribes in today's northern Ethiopia share a common background and cultural heritage in the Kingdom of Aksum (and its successor dynasties) of the first millennium (as well as the first millennium BC kingdom of D’mt), and in its Ethiopian Orthodox Christian Church (today, with an autocephalous Eritrean branch), as well as in its Ge'ez language. Around 90% of today's Eritreans speak languages (Tigrinya and Tigre) that are closely related to the now-extinct Geez language - as do Tigrinya-speakers in northern Ethiopia and Amharic-speakers of Ethiopia, among others.

Recent discoveries, in and around the area of Sembel, near the capital Asmara, show evidence of a society that predated Aksum. These permanent villages and towns predate those of southern Eritrea and northern Ethiopia suggesting, according to Peter Schmidt, "...it is they, not sites in Arabia that were the vital precursors to urban developments...likewise students of evolution and distribution of languages now believe that Semitic and Cushitic languages are of African origin."[6] By Daniel haile Kurkahh.

Kingdom of Aksum

The first verifiable kingdom of great power to rise in Eritrea and Northern Ethiopia was that of Aksum in the 1st century AD. It was one of many successor kingdoms to Dʿmt and was able to unite the northern Ethiopian plateau beginning around the 1st century BC. They established bases on the northern highlands of the Ethiopian Plateau and from there expanded southward. The Persian religious figure Mani listed Axum with Rome, Persia, and China as one of the four great powers of his time. The origins of the Axumite Kingdom are unclear, although experts have offered their speculations about it. Even whom should be considered the earliest known king is contested: although C. Conti Rossini proposed that Zoskales of Axum, mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, should be identified with one Za Haqle mentioned in the Ethiopian King Lists (a view embraced by later historians of Ethiopia such as Yuri M. Kobishchanov[7] and Sergew Hable Sellasie), G.W.B. Huntingford argued that Zoskales was only a sub-king whose authority was limited to Adulis, and that Conti Rossini's identification can not be substantiated.[8]

Inscriptions have been found in southern Arabia celebrating victories over one GDRT, described as "nagashi of Habashat [i.e. Abyssinia] and of Axum." Other dated inscriptions are used to determine a floruit for GDRT (interpreted as representing a Ge'ez name such as Gadarat, Gedur, or Gedara) around the beginning of the 3rd century. A bronze scepter or wand has been discovered at Atsbi Dera with in inscription mentioning "GDR of Axum". Coins showing the royal portrait began to be minted under King Endubis toward the end of the 3rd century.

Christianity was introduced into the country by Frumentius, who was consecrated first bishop of Ethiopia by Saint Athanasius of Alexandria about 330. Frumentius converted Ezana, who has left several inscriptions detailing his reign both before and after his conversion. One inscription found at Axum, states that he conquered the nation of the Bogos, and returned thanks to his father, the god Mars, for his victory. Later inscriptions show Ezana's growing attachment to Christianity, and Ezana's coins bear this out, shifting from a design with disc and crescent to a design with a cross. Expeditions by Ezana into the Kingdom of Kush at Meroe in Sudan may have brought about its demise, though there is evidence that the kingdom was experiencing a period of decline beforehand. As a result of Ezana's expansions, Aksum bordered the Roman province of Egypt. The degree of Ezana's control over Yemen is uncertain. Though there is little evidence supporting Aksumite control of the region at that time, his title, which includes king of Saba and Salhen, Himyar and Dhu-Raydan (all in modern-day Yemen), along with gold Aksumite coins with the inscriptions, "king of the Habshat" or "Habashite," indicate that Aksum might have retained some legal or actual footing in the area.[9]

From the scanty evidence available it would appear that the new religion at first made little progress. Towards the close of the 5th century a great company of monks known as the Nine Saints are believed to have established themselves in the country. Since that time monasticism has been a power among the people and not without its influence on the course of events.

The Axumite Kingdom is recorded once again as controlling part – if not all – of Yemen in the 6th century. Around 523, the Jewish king Dhu Nuwas came to power in Yemen and, announcing that he would kill all the Christians, attacked an Aksumite garrison at Zafar, burning the city's churches. He then attacked the Christian stronghold of Najran, slaughtering the Christians who would not convert. Emperor Justin I of the Eastern Roman empire requested that his fellow Christian, Kaleb, help fight the Yemenite king, and around 525, Kaleb invaded and defeated Dhu Nuwas, appointing his Christian follower Sumuafa' Ashawa' as his viceroy. This dating is tentative, however, as the basis of the year 525 for the invasion is based on the death of the ruler of Yemen at the time, who very well could have been Kaleb's viceroy. Procopius records that after about five years, Abraha deposed the viceroy and made himself king (Histories 1.20). Despite several attempted invasions across the Red Sea, Kaleb was unable to dislodge Abreha, and acquiesced in the change; this was the last time Ethiopian armies left Africa until the 20th century when several units participated in the Korean War. Eventually Kaleb abdicated in favor of his son Wa'zeb and retired to a monastery, where he ended his days. Abraha later made peace with Kaleb's successor and recognized his suzerainty. Despite this reverse, under Ezana and Kaleb the kingdom was at its height, benefiting from a large trade, which extended as far as India and Ceylon, and were in constant communication with the Byzantine Empire.

Details of the Axumite Kingdom, never abundant, become even more scarce after this point. The last king known to mint coins is Armah, whose coinage refers to the Persian conquest of Jerusalem in 614. An early Muslim tradition is that the Negus Ashama ibn Abjar offered asylum to a group of Muslims fleeing persecution during Muhammad's life (615), but Stuart Munro-Hay believes that Axum had been abandoned as the capital by then[10] – although Kobishchanov states that Ethiopian raiders plagued the Red Sea, preying on Arabian ports at least as late as 702.[11]

Some people believed the end of the Axumite Kingdom is as much of a mystery as its beginning. Lacking a detailed history, the kingdom's fall has been attributed to a persistent drought, overgrazing, deforestation, plague, a shift in trade routes that reduced the importance of the Red Sea—or a combination of these factors. Munro-Hay cites the Muslim historian Abu Ja'far al-Khwarazmi/Kharazmi (who wrote before 833) as stating that the capital of "the kingdom of Habash" was Jarma. Unless Jarma is a nickname for Axum (hypothetically from Ge'ez girma, "remarkable, revered"), the capital had moved from Axum to a new site, yet undiscovered.[12]

Medieval history

With the rise of Islam in the 7th century the power of Aksum declined and the Kingdom became isolated, the Dahlak archipelago, northern and western Eritrea, came under increasing control of Islamic powers based in Yemen and Beja lands in Sudan.The Beja were often in alliance with the Umayyads of Arabia who themselves established footholds along stretches of the Eritrean coastline and the Dahlak archipelago while the Funj of Sudan exacted tribute from the adjacent western lowlands of Eritrea.

The culmination of Islamic dominance in the region occurred in 1557 when an Ottoman invasion during the time of Suleiman I and under Özdemir Pasha (who had declared the province of Habesh in 1555) took the port city of Massawa and the adjacent city of Arqiqo, even taking Debarwa, then capital of the local ruler Bahr negus Yeshaq (ruler of Midri Bahri). They administered this area as the province of Habesh. Yeshaq rallied his peasants and recaptured Debarwa, taking all the gold the invaders had piled within. In 1560 Yeshaq, disillusioned with the new Emperor of Ethiopia, revolted with Ottoman support but pledged his support again with the crowning of Emperor Sarsa Dengel. However, not long after, Yeshaq revolted once again with Ottoman support but was defeated once and for all in 1578, leaving the Ottomans with domain over Massawa, Arqiqo and some of the nearby coastal environs, which were soon transferred to the control of Beja Na'ibs (deputies).

Meanwhile the central highlands of Eritrea preserved their Orthodox Christian Aksumite heritage. "There was no administration that connected Hamasin and Serai to the centre of the Ethiopian Kingdom. Indeed, there was little sense in which the Bahr Negash could be said to "control" the area.[13]

The parts of the region were under the domain of Bahr Negash ruled by the Bahr Negus. The region was first referred to as Ma'ikele Bahr ("between the seas/rivers," i.e. the land between the Red Sea and the Mereb river),[14] renamed under Emperor Zara Yaqob as the domain of the Bahr Negash, called Midri Bahri (Tigrinya: "Sea land," though it included some areas like Shire on the other side of the Mereb, today in Ethiopia)[15] until the modern day, when its name was changed to Mereb Mellash (beyond the river Mereb) under the rule of Yohannes IV, the locals referred to this area as Midri Bahri. Medri Bahri was an area distinguished by a very weak feudal structure, with virtually no serfdom and a strong and democratic landowning peasantry unique for the entire region at this time.

The Ottoman state maintained control over much of the northern coastal areas for nearly three hundred years, leaving their possessions (the province of Habesh), to their Egyptian heirs in 1865 before being given to the Italians in 1885. In the southeast of Eritrea, the Sultanate of Awsa, an Afar sultanate, came to dominate the coastline after its founding in 1577, becoming vassal to the Emperor of Ethiopia under the reign of Susenyos I.

Italian colonization

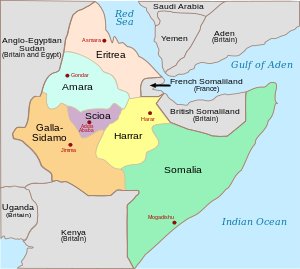

The boundaries of modern Eritrea and the entire region were established during the European colonial period between Italian, British and French colonialists as well as the lone landlocked African Empire of Abyssinia which found itself surrounded and its boundaries defined by said colonial powers.

During the medieval period and prior to the Ottoman occupation of Debarewa in 1557, Eritrea’s historical name was Bahre-Negash (Kingdom of the Sea). Later with the fall of the Kingdom, the area was calledMedri Bahri ("Land of the Sea") until the Italians came to the area in the late 19th century.

The Kingdom of Italy created Eritrea at the end of the nineteenth century, using the classical name for the Red Sea ("erythra"). The colony of Italian Eritrea was established in 1890 (and lasted officially until 1947).

Italian occupation of Massawa and formation of the colony

Later, as the Egyptians retreated out of Sudan during the Mahdist rebellion, the British brokered an agreement whereby the Egyptians could retreat through Ethiopia, and in exchange they would allow the Emperor to occupy those lowland districts that he had disputed with the Turks and Egyptians.

Emperor Yohannes IV believed this included Massawa, but instead, the port was handed by the Egyptians and the British to the Italians, who united it with the already colonised port of Asseb to form a coastal Italian possession. The Italians took advantage of disorder in northern Ethiopia following the death of Emperor Yohannes IV in 1889 to occupy the highlands and established their new colony, henceforth known as Eritrea, and received recognition from Menelik II, Ethiopia's new Emperor.

The Italian possession of maritime areas previously claimed by Abyssinia/Ethiopia was formalized in 1889 with the signing of the Treaty of Wuchale with Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia (r. 1889–1913) after the defeat of Italy by Ethiopia at the battle of Adua where Italy launched an effort to expand its possessions from Eritrea into the more fertile Abyssinian hinterland. Menelik would later renounce the Wuchale Treaty as he had been tricked by the translators to agree to making the whole of Ethiopia into an Italian protectorate. However, he was forced by circumstance to live by the tenets of Italian sovereignty over Eritrea.

The Italians brought to Eritrea a huge development of Catholicism and by the 1940 nearly one third of the Eritrean population was catholic, mainly in Asmara where many churches were built.

Italian administration of Eritrea brought improvements in the medical and agricultural sectors of Eritrean society. Furthermore, the Italians employed many Eritreans in public service (in particular in the police and public works departments) and oversaw the provision of urban amenities in Asmara and Massawa. In a region marked by cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity, a succession of Italian governors maintained a notable degree of unity and public order. The Italians also built many major infrastructural projects in Eritrea, including the Asmara-Massawa Cableway and the Eritrean Railway.[2]

After the establishment of new transportation and communication methods in the country, the Italians also started to set up new factories, which in turn made due contribution in enhancing trade activities. The newly opened factories produced buttons, cooking oil, and pasta, construction materials, packing meat, tobacco, hide and other household commodities. In the year 1939, there were around 2,198 factories and most of the employees were Eritrean citizens, some even moved from the villages to work in the factories.The establishment of industries also made an increase in the number of both Italians and Eritreans residing in the cities. The number of Italians residing in the country increased from 4,600 to 75,000 in five years; and with the involvement of Eritreans in the industries, trade and fruit plantation was expanded across the nation, while some of the plantations were owned by Eritreans.[16]

Benito Mussolini's rise to power in Italy in 1922 brought profound changes to the colonial government in Eritrea. Mussolini established the Italian Empire in May 1936. The fascists imposed harsh rule that stressed the political and racial superiority of Italians. Eritreans were demoted to menial positions in the public sector in 1938.

Eritrea was chosen by the Italian government to be the industrial center of the Italian East Africa.[17]

The Italian government continued to implement agricultural reforms but primarily on farms owned by Italian colonists. The Mussolini government regarded the colony as a strategic base for future aggrandizement and ruled accordingly, using Eritrea as a base to launch its 1935–1936 campaign to colonize Ethiopia.

The best Italian colonial troops were the Eritrean Ascari, as stated by Italian Marshall Rodolfo Graziani and officer Amedeo Guillet [3].

Asmara development

Asmara was populated by a large Italian community and the city acquired an Italian architectural look. One of the first building was the Asmara President's Office: this former "Italian government's palace" was built in 1897 by Ferdinando Martini, the first Italian governor of Eritrea. The Italian government wanted to create in Asmara an impressive building, from where the Italian Governors could show the dedication of the Kingdom of Italy to the "colonia primogenita" (first daughter-colony) as was called Eritrea.[18]

Today Asmara is worldwide known for its early twentieth century Italian buildings, including the Art Deco Cinema Impero, "Cubist" Africa Pension, eclectic Orthodox Cathedral and former Opera House, the futurist Fiat Tagliero Building, neo-Romanesque Roman Catholic Cathedral, and the neoclassical Governor's Palace. The city is littered with Italian colonial villas and mansions. Most of central Asmara was built between 1935 and 1941, so effectively the Italians managed to build almost an entire city, in just six years.[19]

The city of Asmara had a population of 98,000, of which 53,000 were Italians according to the Italian census of 1939. This fact made Asmara the main "Italian town" of the Italian empire in Africa.In all Eritrea the Italian Eritreans were 75,000 in that year.[4]

Many industrial investments were done by the Italians in the area of Asmara and Massawa, but the beginning of World War II stopped the blossoming industrialization of Eritrea. When the British army conquered Eritrea from the Italians in spring 1941, most of the infrastructures and the industrial areas were extremely damaged.

The following Italian guerrilla war was supported by many Eritrean colonial troops until the Italian armistice in September 1943. Eritrea was placed under British military administration after the Italian surrender in World War II.

The Italian Eritreans strongly rejected the Ethiopian annexation of Eritrea after the war: the Party of Shara Italy was established in Asmara in July 1947 and the majority of the members were former Italian soldiers with many Eritrean Ascari (the organization was even backed up by the government of Italy). The main objective of this party was Eritrea freedom but they had a pre-condition that stated that before independence the country should be governed by Italy for at least 15 years (like happened with Italian Somalia).

British administration and federalization

British forces defeated the Italian army in Eritrea in 1941 at the Battle of Keren and placed the colony under British military administration until Allied forces could determine its fate. The first thing the British did was to remove the Eritrean industries (of Asmara and Massawa) to Kenya, as war compensation. They even dismantled parts of the Eritrean Railway system.[20]

In the absence of agreement amongst the Allies concerning the status of Eritrea, British administration continued for the remainder of World War II and until 1950. During the immediate postwar years, the British proposed that Eritrea be divided along religious lines and parceled off to Sudan and Ethiopia. The Soviet Union, anticipating a communist victory in the Italian polls, initially supported returning Eritrea to Italy under trusteeship or as a colony. Arab states, seeing Eritrea and its large Muslim population as an extension of the Arab world, sought the establishment of an independent state.

Ethiopian ambition in the Horn was apparent in the expansionist ambition of its monarch when Haile Selassie claimed Italian Somaliland and Eritrea. He made this claim in a letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt, at the Paris Peace Conference and at the First Session of the United Nations.[21] In the United Nations the debate over the fate of the former Italian colonies continued. The British and Americans preferred to cede Eritrea to the Ethiopians as a reward for their support during World War II. "The United States and the United Kingdom have (similarly) agreed to support the cession to Ethiopia of all of Eritrea except the Western province. The United States has given assurances to Ethiopia in this regard."[22] The Independence Bloc of Eritrean parties consistently requested from the UN General Assembly that a referendum be held immediately to settle the Eritrean question of sovereignty.

A United Nations (UN) commission was dispatched to the former colony in February 1950 in the absence of Allied agreement and in the face of Eritrean demands for self-determination. It was also at this juncture that the US Ambassador to the UN, John Foster Dulles, said, "From the point of view of justice, the opinions of the Eritrean people must receive consideration. Nevertheless the strategic interest of the United States in the Red Sea basin and the considerations of security and world peace make it necessary that the country has to be linked with our ally Ethiopia."[23] The Ambassador's word choice, along with the estimation of the British Ambassador in Addis Ababa, makes quite clear the fact that the Eritrea aspiration was for Independence.[21]

The commission proposed the establishment of some form of association with Ethiopia, and the UN General Assembly adopted that proposal along with a provision terminating British administration of Eritrea no later than September 15, 1952. The British, faced with a deadline for leaving, held elections on March 16, 1952, for a representative Assembly of 68 members, evenly divided between Christians and Muslims. This body in turn accepted a draft constitution put forward by the UN commissioner on July 10. On September 11, 1952, Emperor Haile Selassie ratified the constitution. The Representative Assembly subsequently became the Eritrean Assembly. In 1952 the United Nations resolution to federate Eritrea with Ethiopia went into effect.

The resolution ignored the wishes of Eritreans for independence, but guaranteed the population some democratic rights and a measure of autonomy. Some scholars have contended that the issue was a religious issue, between the Muslim lowland population desiring independence while the highland Christian population sought a union with Ethiopia. Other scholars, including the former Attorney-General of Ethiopia, Bereket Habte Selassie, contend that, "religious tensions here and there...were exploited by the British, [but] most Eritreans (Christians and Moslems) were united in their goal of freedom and independence."[21] Almost immediately after the federation went into effect, however, these rights began to be abridged or violated. These pleas for independence and referendum augured poorly for the US, Britain and Ethiopia, as a confidential American estimate of Independence Party support amounted to 75% of Eritrea.[24]

The details of Eritrea's association with Ethiopia were established by the UN General Assembly resolution of September 15, 1952. It called for Eritrea and Ethiopia to be linked through a loose federal structure under the sovereignty of the Emperor. Eritrea was to have its own administrative and judicial structure, its own flag, and control over its domestic affairs, including police, local administration, and taxation.[21] The federal government, which for all intents and purposes was the existing imperial government, was to control foreign affairs (including commerce), defense, finance, and transportation. As a result of a long history of a strong landowning peasantry and the virtual absence of serfdom in most parts of Eritrea, the bulk of Eritreans had developed a distinct sense of cultural identity and superiority vis-à-vis Ethiopians. This combined with the introduction of modern democracy into Eritrea by the British administration gave Eritreans a desire for political freedoms alien to Ethiopian political tradition. From the start of the federation, however, Haile Selassie attempted to undercut Eritrea’s independent status, a policy that alienated many Eritreans. The Emperor pressured Eritrea’s elected chief executive to resign, made Amharic the official language in place of Arabic and Tigrinya, terminated the use of the Eritrean flag, imposed censorship, and moved many businesses out of Eritrea. Finally, in 1962 Haile Selassie pressured the Eritrean Assembly to abolish the Federation and join the Imperial Ethiopian fold, much to the dismay of those in Eritrea who favored a more liberal political order.

War for independence

Militant opposition to the incorporation of Eritrea into Ethiopia had begun in 1958 with the founding of the Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM), an organization made up mainly of students, intellectuals, and urban wage laborers. The ELM, under the leadership of Hamid Idris Awate, a former Eritrean Ascari, engaged in clandestine political activities intended to cultivate resistance to the centralizing policies of the imperial Ethiopian state. By 1962, however, the ELM had been discovered and destroyed by imperial authorities.

Emperor Haile Selassie unilaterally dissolved the Eritrean parliament and annexed the country in 1962. The war continued after Haile Sellassie was ousted in a coup in 1974. The Derg, the new Ethiopian government, was a Marxist military junta led by strongman Mengistu Haile Mariam.

During the 1960s, the Eritrean independence struggle was led by the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF). In 1960 Eritrean exiles in Cairo founded the Eritrean Liberation Front. In contrast to the ELM, from the outset the ELF was bent on waging armed struggle on behalf of Eritrean independence. The ELF was composed mainly of Eritrean Muslims from the rural lowlands on the western edge of the territory. In 1961 the ELF's political character was vague, but radical Arab states such as Syria and Iraq sympathized with Eritrea as a predominantly Muslim region struggling to escape Ethiopian oppression and imperial domination. These two countries therefore supplied military and financial assistance to the ELF.

The ELF initiated military operations in 1961 and intensified its activities in response to the dissolution of the federation in 1962. By 1967 the ELF had gained considerable support among peasants, particularly in Eritrea's north and west, and around the port city of Massawa. Haile Selassie attempted to calm the growing unrest by visiting Eritrea and assuring its inhabitants that they would be treated as equals under the new arrangements. Although he doled out offices, money, and titles mainly to Christian highlanders in the hope of co-opting would-be Eritrean opponents in early 1967, the imperial secret police of Ethiopia also set up a wide network of informants in Eritrea and conducted disappearances, intimidations and assassinations among the same populace driving several prominent political figures into exile. Imperial police fired live ammunition killing scores of youngsters during several student demonstrations in Asmara in this time. The imperial army also actively perpetrated massacres until the ousting of the Emperor by the Derg in 1974.

By 1971 ELF activity had become enough of a threat that the emperor had declared martial law in Eritrea. He deployed roughly half of the Ethiopian army to contain the struggle. Internal disputes over strategy and tactics eventually led to the ELF's fragmentation and the founding in 1972 of the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF). The leadership of this multi-ethnic movement came to be dominated by leftist, Christian dissidents who spoke Tigrinya, Eritrea's predominant language. Sporadic armed conflict ensued between the two groups from 1972 to 1974, even as they fought Ethiopian forces. By the late 1970s, the EPLF had become the dominant armed Eritrean group fighting against the Ethiopian Government, and Isaias Afewerki had emerged as its leader. Much of the material used to combat Ethiopia was captured from the army.

By 1977 the EPLF was poised to drive the Ethiopians out of Eritrea. However, that same year a massive airlift of Soviet arms to Ethiopia enabled the Ethiopian Army to regain the initiative and forced the EPLF to retreat to the bush. Between 1978 and 1986 the Derg launched eight unsuccessful major offensives against the independence movement. In 1988 the EPLF captured Afabet, headquarters of the Ethiopian Army in northeastern Eritrea, putting approximately a third of the Ethiopian Army out of action, prompting the Ethiopian Army to withdraw from its garrisons in Eritrea's western lowlands. EPLF fighters then moved into position around Keren, Eritrea's second-largest city. Meanwhile, other dissident movements were making headway throughout Ethiopia. At the end of the 1980s the Soviet Union informed Mengistu that it would not be renewing its defense and cooperation agreement. With the withdrawal of Soviet support and supplies, the Ethiopian Army's morale plummeted, and the EPLF, along with other Ethiopian rebel forces, began to advance on Ethiopian positions. In 1980 the Permanent Peoples' Tribunal determined that the right of the Eritrean people to self-determination does not represent a form of secession.[13]

Establishing an independent country

The United States played a facilitative role in the peace talks in Washington during the months leading up to the May 1991 fall of the Mengistu regime. In mid-May, Mengistu resigned as head of the Ethiopian Government and went into exile in Zimbabwe, leaving a caretaker government in Addis Ababa. Having defeated the Ethiopian forces in Eritrea, EPLF troops took control of their homeland. Later that month, the United States chaired talks in London to formalize the end of the war. These talks were attended by the four major combatant groups, including the EPLF.

Following the collapse of the Mengistu government, Eritrean independence began drawing influential interest and support from the United States. Heritage Foundation Africa expert Michael Johns wrote that "there are some modestly encouraging signs that the front intends to abandon Mengistu's autocratic practices."[25]

A high-level U.S. delegation was also present in Addis Ababa for the July 1–5, 1991 conference that established a transitional government in Ethiopia. The EPLF attended the July conference as an observer and held talks with the new transitional government regarding Eritrea's relationship to Ethiopia. The outcome of those talks was an agreement in which the Ethiopians recognized the right of the Eritreans to hold a referendum on independence.

Although some EPLF cadres at one time espoused a Marxist ideology, Soviet support for Mengistu had cooled their ardor. The fall of communist regimes in the former Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc convinced them it was a failed system. The EPLF now says it is committed to establishing a democratic form of government and a free-market economy in Eritrea. The United States agreed to provide assistance to both Ethiopia and Eritrea, conditional on continued progress toward democracy and human rights.

In May 1991 the EPLF established the Provisional Government of Eritrea (PGE) to administer Eritrean affairs until a referendum was held on independence and a permanent government established. EPLF leader Afewerki became the head of the PGE, and the EPLF Central Committee served as its legislative body.

Eritreans voted overwhelmingly in favor of independence between 23 and 25 April 1993 in a UN-monitored referendum. The result of the referendum was 99.83% for Eritrea's independence. The Eritrean authorities declared Eritrea an independent state on 27 April. The government was reorganized and the National Assembly was expanded to include both EPLF and non-EPLF members. The assembly chose Isaias Afewerki as President. The EPLF reorganized itself as a political party, the People's Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ).

1990s

In July 1996 the Constitution of Eritrea was ratified, but it has yet to be implemented.

In 1998 a border dispute with Ethiopia, over the town of Badme, led to the Eritrean-Ethiopian War in which thousands of soldiers from both countries died. Eritrea suffered from significant economic and social stress, including massive population displacement, reduced economic development, and one of Africa's more severe land mine problems.

The border war ended in 2000 with the signing of the Algiers Agreement. Amongst the terms of the agreement was the establishment of a UN peacekeeping operation, known as the United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE); with over 4,000 UN peacekeepers. The UN established a temporary security zone consisting of a 25-kilometre demilitarized buffer zone within Eritrea, running along the length of the disputed border between the two states and patrolled by UN troops. Ethiopia was to withdraw to positions held before the outbreak of hostilities in May 1998. The Algiers agreement called for a final demarcation of the disputed border area between Eritrea and Ethiopia by the assignment of an independent, UN-associated body known as the Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission (EEBC), whose task was to clearly identify the border between the two countries and issue a final and binding ruling. The peace agreement would be completed with the implementation of the Border Commission's ruling, which would also end the task of the peacekeeping mission. After extensive study, the Commission issued a final border ruling in April 2002, which awarded some territory to each side, but Badme (the flash point of the conflict) was awarded to Eritrea. The Commission's decision was rejected by Ethiopia. The border question remains in dispute, with Ethiopia refusing to withdraw its military from positions in the disputed areas, including Badme, while a "difficult" peace remains in place.

The UNMEE mission was formally abandoned in July 2008, after experiencing serious difficulties in sustaining its troops after fuel stoppages.

Furthermore, Eritrea's diplomatic relations with Djibouti were briefly severed during the border war with Ethiopia in 1998 due to a dispute over Djibouti's intimate relation with Ethiopia during the war but were restored and normalized in 2000. Relations are again tense due to a renewed border dispute. Similarly, Eritrea and Yemen had a border conflict between 1996 to 1998 over the Hanish Islands and the maritime border, which was resolved in 2000 by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague.

Contemporary Eritrea

Roughly 10% of the population of Eritrea works in the public sector, fuel is strictly rationed, and all media outlets are state-run. Health care is cheaply available where it exists, and there are state-run campaigns concerning issues such as HIV infection and female genital mutilation.

Due to his frustration with the stalemated peace process with Ethiopia, the President of Eritrea Isaias Afewerki wrote a series of Eleven Letters to the UN Security Council and Secretary-General Kofi Annan. Despite the Algiers Agreement, tense relations with Ethiopia have continued and led to regional instability.

His government has also been condemned for allegedly arming and financing the insurgency in Somalia; the United States is considering labeling Eritrea a "State Sponsor of Terrorism,"[26] however, many experts on the topic have shied from this assertion, stating that "If there is one country where the fighting of extremists and terrorists was a priority when it mattered, it was Eritrea."[27]

In December 2007, an estimated 4000 Eritrean troops remained in the 'demilitarized zone' with a further 120,000 along its side of the border. Ethiopia maintained 100,000 troops along its side.[28]

In September, 2012, the Israeli 'Haaretz' newspaper published an expose on Eritrea. There are over 40,000 Eritrean refugees in Israel. [29] Eritrea has been nicknamed as the "North Korea of Africa," and is among the harshest dictatorships in the world, where limitations on freedom of movement are extreme and punishments severe. The group 'Doctors Without Borders' ranks the place 179th among 179 countries when it comes to freedom of expression, even lower than North Korea. One of the most glaring reflections of the harshness of the regime in Asmara, the Eritrean capital, is the mandatory military service that citizens on average serve from age 18 until they are 55 and which has spurred many to flee. 'Amnesty International' notes that in a country where the average life expectancy is 61 or 62, this means many spend their entire adult lives in the army, frequently facing hard labor and meager wages. Women have fled the army because the army bars them from getting pregnant, denying them the opportunity to start a family if they remained in the Eritrean military. On the other hand, Eritrean army officers have the right to have sex with subordinate female soldiers, as it's not legally considered rape. Every month about 3,000 people flee the East African country. According to a recent United Nations report, more than 84 percent of Eritreans who have sought asylum around the world have been recognized as refugees deserving asylum status.

Continuing border conflicts

On 19 June 2008 the BBC published a time line of the conflict and reported that the "Border dispute rumbles on":

- 2007 September – War could resume between Ethiopia and Eritrea over their border conflict, warns United Nations special envoy to the Horn of Africa, Kjell Magne Bondevik.

- 2007 November – Eritrea accepts border line demarcated by international boundary commission. Ethiopia rejects it.

- 2008 January – UN extends mandate of peacekeepers on Ethiopia-Eritrea border for six months. UN Security Council demands Eritrea lift fuel restrictions imposed on UN peacekeepers at the Eritrea-Ethiopia border area. Eritrea declines, saying troops must leave border.

- 2008 February – UN begins pulling 1,700-strong peacekeeper force out due to lack of fuel supplies following Eritrean government restrictions.

- 2008 April – UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon warns of likelihood of new war between Ethiopia and Eritrea if peacekeeping mission withdraws completely. Outlines options for the future of the UN mission in the two countries.

- Djibouti accuses Eritrean troops of digging trenches at disputed Ras Doumeira border area and infiltrating Djiboutian territory. Eritrea denies charge.

- 2008 May – Eritrea calls on UN to terminate peacekeeping mission.

- 2008 June – Fighting breaks out between Eritrean and Djiboutian troops.

— BBC[30]

See also

Further reading

- Beretekeab R. (2000); Eritrean making of a Nation 1890-1991, Uppsala University, Uppsala.

- Mauri, Arnaldo (2004); Eritrea's early stages in monetary and banking development, International Review of Economics,ISSN 1865-1704, Vol. 51, n. 4, pp. 547-569.

- Negash T. (1987); Italian colonisation in Eritrea: policies, praxis and impact, Uppsala University, Uppsala.

- Wrong, Michela. I Didn't Do It For You : How the World Used and Abused a Small African Nation. Harper Perennial (2005). ISBN 0-00-715095-4

References

- ^ McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology (9th ed.). The McGraw Hill Companies Inc. 2002. ISBN 0-07-913665-6.

- ^ Walter, Robert C.; Buffler, RT; Bruggemann, JH; Guillaume, MM; Berhe, SM; Negassi, B; Libsekal, Y; Cheng, H; Edwards, RL (2000-05-04). "Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the lastinterglacial". Nature. 405 (6782): 65–69. doi:10.1038/35011048. PMID 10811218. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ "Out of Africa". 1999-09-10. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ "Pleistocene Park". 1999-09-08. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ Simson Najovits, Egypt, trunk of the tree, Volume 2, (Algora Publishing: 2004), p.258.

- ^ Greenfield, Richard. "New discoveries in Africa change face of history". New African (November 2001). IC Publication. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ^ Yuri M. Kobishchanov, Axum, Joseph W. Michels, editor; Lorraine T. Kapitanoff, translator, (University Park, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania, 1979), pp.54-59.

- ^ Expressed, for example, in his The Historical Geography of Ethiopia (London: the British Academy, 1989), p.39.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum, p. 81.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum, p.56.

- ^ Kobishchanov, Axum, p.116.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum, pp.95-98.

- ^ a b "Proceedings of the Permanent Peoples' Tribunal of the International League for the Rights and Liberation of Peoples". Session on Eritrea. Rome, Italy: Research and Information Centre on Eritrea. 1984.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (1270–1527) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p.74.

- ^ Daniel Kendie, The Five Dimensions of the Eritrean Conflict 1941–2004: Deciphering the Geo-Political Puzzle. United States of America: Signature Book Printing, Inc., 2005, pp.17-8.

- ^ Italian administration in Eritrea

- ^ Italian industries in colonial Eritrea

- ^ Ferdinando Martini.RELAZIONE SULLA COLONIA ERITREA - Atti Parlamentari - Legislatura XXI - Seconda Sessione 1902 - Documento N. XVI -Tipografia della Camera dei Deputati. Roma, 1902

- ^ "Reviving Asmara". BBC 3 Radio. 2005-06-19. Retrieved 2006-08-30. [dead link]

- ^ First reported by Sylvia Pankhurst in her book, Eritrea on the Eve (1947). See Michela Wrong, I didn't do it for you: How the World betrayed a small African nation (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), chapter 6 "The Feminist Fuzzy-wuzzy"

- ^ a b c d Habte Selassie, Bereket (1989). Eritrea and the United Nations. Red Sea Press. ISBN 0-932415-12-1.

- ^ Top Secret Memorandum of 1949-03-05, written with the UN Third Session in view, from Mr. Rusk to the Secretary of State.

- ^ Heiden, Linda (1979). "The Eritrean Struggle for Independence". Monthly Review. 30 (2): 15.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Department of State, Incoming Telegram, received 1949-08-22, From Addis Ababa, signed MERREL, to Secretary of State, No. 171, 1949-08-19

- ^ "Does Democracy Have a Chance?" by Michael Johns, The World and I magazine, August 1991 (entered in The Congressional Record, May 6, 1992).

- ^ "US Considers Terror Label for Eritrea". London. Archived from the original on 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (2007-09-18). "Eritreans Deny American Accusations of Terrorist Ties". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ "Ethiopia and Eritrea: Bad words over Badme", The Economist, 13 December 2007

- ^ Halper, Yishai (7 September 2012). "'The North Korea of Africa': Where you need a permit to have dinner with friends". Haaretz. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ [1], BBC, 19 June 2008

External links

- Background Note: Eritrea

- History of Eritrea

- The Eritrean railway (in Italian)

- Photos of Italian Eritrea, from the website of the Italians of Eritrea (in Italian)

Further reading

- Peter R. Schmidt, Matthew C. Curtis and Zelalem Teka, The Archaeology of Ancient Eritrea. Asmara: Red Sea Press, 2008. 469 pp. ISBN 1-56902-284-4