History of the United States foreign policy

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

History of the United States foreign policy is a brief overview of major trends regarding the foreign policy of the United States from the American Revolution to the present. The major themes are becoming an "Empire of Liberty", promoting democracy, expanding across the continent, supporting liberal internationalism, contesting World Wars and the Cold War, fighting international terrorism, developing the Third World, and building a strong world economy with low tariffs (but high tariffs in 1861-1933).

New nation: 1776–1801

[edit]Revolution and Confederation

[edit]

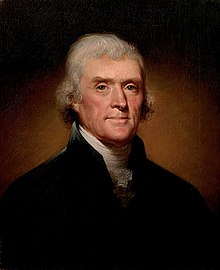

From the establishment of the United States after regional, not global, focus, but with the long-term ideal of creating what Jefferson called an "Empire of Liberty."

The military and financial alliance with France in 1778, which brought in Spain and the Netherlands to fight the British, turned the American Revolutionary War into a world war in which the British naval and military supremacy was neutralized. The diplomats—especially Franklin, Adams and Jefferson—secured recognition of American independence and large loans to the new national government. The Treaty of Paris in 1783 was highly favorable to the United States which now could expand westward to the Mississippi River.

Historian Samuel Flagg Bemis was a leading expert on diplomatic history. According to Jerold Combs:

- Bemis's The Diplomacy of the American Revolution, published originally in 1935, is still the standard work on the subject. It emphasized the danger of American entanglement in European quarrels. European diplomacy in the eighteenth century was "rotten, corrupt, and perfidious," warned Bemis. America's diplomatic success had resulted from staying clear of European politics while reaping advantage from European strife. Franklin, Jay, and Adams had done just this during the Revolution and as a consequence had won the greatest victory in the annals of American diplomacy. Bemis conceded that the French alliance had been necessary to win the war. Yet he regretted that it had brought involvement with "the baleful realm of European diplomacy." Vergennes [the French foreign minister] was quite willing to lead America to an "abattoir" [slaughterhouse] where portions of the United States might be dismembered if this would advance the interests of France.[1]

American foreign affairs from independence in 1776 to the new Constitution in 1789 were handled under the Articles of Confederation directly by Congress until the new government created a department of foreign affairs and the office of secretary for foreign affairs on January 10, 1781.[2]

Early National Era: 1789–1801

[edit]The cabinet-level Department of Foreign Affairs was created in 1789 by the First Congress. It was soon renamed the Department of State and changed the title of secretary for foreign affairs to Secretary of State; Thomas Jefferson returned from France to take the position. His rival Alexander Hamilton often won Washington's support and outmanoeuvred Jefferson in setting foreign policy.[citation needed]

Jay Treaty with Britain alienates Jeffersonians

[edit]When the French Revolution led to war in 1793 between Britain (America's leading trading partner), and France (the old ally, with a treaty still in effect), Washington and his cabinet decided on a policy of neutrality, as enshrined in the Neutrality Act of 1794. In 1795 Washington supported the Jay Treaty, designed by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton to avoid war with Britain and encourage commerce. The Jeffersonians led by Jefferson and James Madison vehemently opposed the treaty, but Washington's support proved decisive, and the U.S. and Britain were on friendly terms for a decade. However the foreign policy dispute polarized Americans and caused the emerge of two rival parties: the Federalists led by Hamilton and the Republicans led by Jefferson and Madison. See First Party System.[3][4]

In his "Farewell Message" that became a foundation of policy President George Washington in 1796 counseled against foreign entanglements:[5]

Europe has a set of primary interests, which to us have none, or a very remote relation. Hence she must be engaged in frequent controversies, the causes of which are essentially foreign to our concerns. Hence therefore it must be unwise in us to implicate ourselves, by artificial ties, in the ordinary vicissitudes of her politics, or the ordinary combinations & collisions of her friendships, or enmities. Our detached & distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course.

Trouble with France: XYZ Affair and Quasi-War

[edit]In 1798, the French demanded American diplomats pay huge bribes in order to meet with Foreign Minister Talleyrand, which the Americans rejected. The Republicans, suspicious of Adams, demanded the documentation, which Adams released using X, Y and Z as codes for the names of the French diplomats. The XYZ Affair ignited a wave of nationalist sentiment. Congress approved Adams' plan to organize the navy. American public opinion swung against France, encouraging the Federalists to attempt to suppress Jefferson's Republican Party. Adams reluctantly signed the Alien and Sedition Acts designed to weaken the Republicans. However Adams broke with the Hamiltonian wing of his Federalist Party and made peace with France in 1800. The Federalist party now split, and was unable to reelect Adams in 1800; it never regained power. However, the Republicans hated Napoleon, and no longer supported France in its war with Britain.[6]

By 1798 French privateers were openly seizing American ships, leading to an undeclared war known as the Quasi-War of 1798–99. It was an undeclared naval conflict with the French First Republic from 1798 to 1800. The French were at war with Great Britain, while the U.S. was neutral. The dispute began due to different interpretations of treaties and escalated when France seized American ships trading with Britain. Diplomatic negotiations failed. Congress reassembled the United States Navy and authorized force against France in 1798. In February 1799, President Adams declared that he would negotiate peace. However, his own Federalist Party was split between his moderates and Hamilton's high Federalists who wanted to keep fighting. The chances of reaching a peaceful agreement were enhanced by Napoleon's rise to power in France, as he believed the Quasi-War was taking away from the main war against Britain. The Quasi-War came to an end with the signing of the Convention of 1800 in September, but news of the peace only arrived after Adams lost the 1800 election to the Republicans. Despite opposition from high Federalists, Adams was able to get the convention ratified by the Senate in the lame-duck session of Congress. He then disbanded the emergency army, which he had never used.[7]

The ability of Congress to authorize military action without a formal declaration of war was later confirmed by the Supreme Court.[8]

Jeffersonian Era: 1801–1829

[edit]

Thomas Jefferson envisioned America as the force behind a great "Empire of Liberty",[9] that would promote republicanism and counter British influence in North America. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803, made by Jefferson in a $15 million deal with Napoleon Bonaparte, doubled the size of the growing nation by adding a huge swath of territory west of the Mississippi River, opening up millions of new farm sites for the yeomen farmers idealized by Jeffersonian Democracy.[10]

President Jefferson planned the Embargo Act of 1807 to force Europe to comply. It forbade trade with both France and Britain, but they did not bend. Furthermore, Federalists denounced his policy as partisanship in favor of agrarian interests instead of commercial interests. It was highly unpopular in New England, which began smuggling operations, and proved ineffective in stopping seizures of American merchantmen by British warships.[11]

War of 1812

[edit]

The Jeffersonians deeply distrusted the British in the first place, but this was exacerbated by the Royal Navy closing U.S. trade with France and impressing about 6,000 alleged British deserters from American ships. The American public felt humiliated by the British attack on the American warship Chesapeake in 1807.[12] In the west, British-allied Indians attacked American colonizers, thus frustrating the encroachment of U.S. frontier settlements into the Midwest (Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan, especially).[13]

In 1812 diplomacy had broken down and the U.S. declared war on Britain. The War of 1812 was marked by very bad planning and military fiascoes on both sides. It ended with the Treaty of Ghent in 1815. Militarily it was a stalemate as both sides failed in their invasion attempts, but the Royal Navy blockaded the coastline and shut down American trade (except for smuggling supplies into British Canada). However the British achieved their main goal of defeating Napoleon, while the American armies defeated the Indian alliance that the British had supported, ending the British war goal of establishing a pro-British Indian boundary nation in the Midwest and giving them territorial advantage over the U.S. The British stopped impressing sailors on American ships and trade with France (now an ally of Britain) resumed, so the causes of the war had been cleared away. Especially after the American victory at the Battle of New Orleans, Americans felt proud and triumphant for having won their "second war of independence."[14] Successful generals Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison became political heroes as well. After 1815 tensions de-escalated along the U.S.-Canada border, with peaceful trade and generally good relations. Boundary disputes were settled amicably. Both the U.S. and Canada saw a surge in nationalism and national pride after 1815.[citation needed]

After 1780, the United States opened relations with North African countries, and with the Ottoman Empire.[15]

Latin America

[edit]In response to the new independence of Spanish colonies in Latin America in 1821, the United States, in implicit cooperation with Great Britain, established the Monroe Doctrine in 1823.[16] This policy declared opposition to European interference in the Americas and left a lasting imprint on the psyche of later American leaders. The failure of Spain to colonize or police Florida led to its purchase by the U.S. in 1821. John Quincy Adams was Secretary of State under President Monroe.[17][18]

Jacksonian Era: 1829–1861

[edit]Mexican–American War

[edit]

In 1846 after an intense political debate in which the expansionist Democrats prevailed over the Whigs, the U.S. annexed the Republic of Texas. Mexico never recognized that Texas had achieved independence and promised war should the U.S. annex it. President James K. Polk peacefully resolved a border dispute with Britain regarding Oregon, then sent U.S. Army patrols into the disputed area of Texas. That triggered the Mexican–American War, which the Americans won easily. As a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 the U.S. acquired territory that included California, Arizona, and New Mexico, and the Hispanic residents there were given full U.S. citizenship.[19]

Nicaraguan canal

[edit]The British wanted a stable Mexico to block American expansion to the Southwest, but the Americans invaded Mexico before the Mexicans could stabilize themselves. The result was a vast American expansion. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 brought a heavy demand for passage to the gold fields, with the main routes crossing Panama to avoid a very long slow sailing voyage around all of South America. A railroad was built that carried 600,000 despite the dangerous environment in Panama. A canal in Nicaragua was a much healthier and attractive possibility, and American businessman Cornelius Vanderbilt gained the necessary permissions, along with a U.S. treaty with Nicaragua. Britain had long dominated Central America, but American influence was growing, and several governments in the region looked to the United States as a counterweight to British influence. However the British were determined to block an American canal, and controlled key locations on the Mosquito Coast on the Atlantic that blocked it. The Whigs were in charge in Washington and unlike the bellicose Democrats wanted a business-like peaceful solution. The Whigs took a lesson from the British experience monopolizing the chokepoint of Gibraltar, which resulted in large amounts of military expenses. The United States decided that a canal should be open and neutral to all the world's traffic, and not be militarized. Tensions escalated locally, with small-scale physical confrontations in the field.[20][additional citation(s) needed]

In the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850 Washington and London found a diplomatic solution. To avert an escalating clash it focused on a Nicaragua Canal that would connect the Pacific and the Atlantic. The three main treaty provisions stated that neither nation would build such a canal without the consent and cooperation of the other; neither would fortify or found new colonies in the region; if and when a canal was built, both powers would guarantee that it would be available on a neutral basis for all shipping. However, disagreements arose and no Nicaragua canal was ever started, but the treaty remained in effect until 1901. By 1857–59, London dropped its opposition to American territorial expansion.[21][additional citation(s) needed]

The opening of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 made travel to California very fast, cheap and safe. It took six days from Chicago instead of six months. Americans lost interest in canals and focused their attention on building long-distance railways. The British, meanwhile, turned their attention to the Suez Canal for fast access to India. London maintained a veto on American canal building in Nicaragua. In 1890s, the French made a major effort to build a canal through Panama, but it self-destructed through mismanagement, severe corruption, and especially the deadly disease environment. By the late 1890s Britain saw the need for much improved relations with the United States, and agreed to allow the U.S. to build a canal through either Nicaragua or Panama. The choice was Panama. The Hay–Pauncefote Treaty of 1901 replaced the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty, and adopted the rule of neutralization for the Panama Canal which the U.S. built; it opened in 1914.[22][23]

President Buchanan, 1857-1861

[edit]Buchanan had a great deal of experience in foreign policy and entered the White House with an ambitious foreign policy, but he and Secretary of State Lewis Cass had very little success. The primary obstacle was opposition from Congress. His ambitions centered around establishing American hegemony over Central America at the expense of Great Britain.[24] He hoped to re-negotiate the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, which he viewed as a mistake that limited U.S. influence in the region. He also sought to establish American protectorates over the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora, In part as a destination for Mormons.[25]

Aware of the decrepit state of the Spanish Empire, he hoped to finally achieve his long-term goal of acquiring Cuba, where slavery still flourished. After long negotiations with the British, he convinced them to agree to cede the Bay Islands to Honduras and the Mosquito Coast to Nicaragua. However, Buchanan's ambitions in Cuba and Mexico were blocked in the House of Representatives where the anti-slavery forces strenuously opposed any move to acquire new slave territory. Buchanan was assisted by his ally Senator John Slidell (D.-Louisiana). But Senator Stephen Douglas, a bitter enemy of Buchanan inside the Democratic Party, worked hard to frustrate Buchanan's foreign-policy.[26][27]

Buchanan tried to purchase Alaska from Russia, possibly as a colony for Mormon settlers, but the U.S. and Russia were unable to agree upon a price.[citation needed]

In China, the U.S. did not take direct part in the Second Opium War, but the Buchanan administration did gain trade concessions. The president relied on William Bradford Reed (1806–1876) his Minister to China in 1857–58. A former Whig, Reed had persuaded many old-line Whigs to support Buchanan in the 1856 campaign. The Treaty of Tientsin (1858) granted American diplomats the right to reside in Peking, reduced tariff levels for American goods, and guaranteed the free exercise of religion by foreigners in China. Reed developed some of the roots of the Open Door Policy that came to fruition 40 years later.[28][29]

In 1858, Buchanan was angered by "A most unprovoked, unwarrantable, and dastardly attack" and ordered the Paraguay expedition. Its successful mission was to punish Paraguay for firing on the USS Water Witch which was on a scientific expedition. Paraguay apologized and paid an indemnity.[30]

Missionaries to China, 1830–1940s

[edit]

The first American missionary in China was Elijah Coleman Bridgman (1801–61), who arrived in 1830. He soon transcended his prejudices against Chinese "idolatry," learned the Chinese language, and wrote a widely used history of the United States in Chinese. He founded the English-language journal The Chinese Repository in 1832, and it served as a major American source of information on Chinese culture and politics.[31]

According to John Pomfret, the American missionaries were crucial to China's development. Along with Western-educated Chinese, they supplied the tools to break the stranglehold of traditional orthodoxy. They taught Western science, critical thinking, sports, industry, and law. They established China's first universities and hospitals. These institutions, though now renamed, are still the best of their kind in China.[32]

The women missionaries played a special role. They organized moralistic crusades against the traditional customs of female infanticide and foot-binding, helping to accomplish what Pomfret calls "the greatest human rights advances in modern Chinese history."[33][34] Missionaries used physical education and sports to promote healthy life styles, to overturn class conventions by showing how the poor could excel, and by expanding gender roles using women's sports.[35][36]

During the Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901, Christian missions were burned, thousands of converts were executed, and the American missionaries barely escaped with their lives.[37]

Paul Varg argues that American missionaries worked very hard on changing China:

The growth of the missionary movement in the first decades of the [20th] century wove a tie between the American church-going public and China that did not exist between the United States and any other country. The number of missionaries increased from 513 in 1890 to more than 2,000 in 1914, and by 1920 there were 8,325 Protestant missionaries in China. In 1927 there were sixteen American universities and colleges, ten professional schools of collegiate rank, four schools of theology, and six schools of medicine. These institutions represented an investment of $19 million. By 1920, 265 Christian middle schools existed with an enrollment of 15,213. There were thousands of elementary schools; the Presbyterians alone had 383 primary schools with about 15,000 students.[38]

Extensive fund-raising and publicity campaigns were held across the U.S. The Catholics in America also supported large mission operations in China.[39]

President Woodrow Wilson was in touch with his former Princeton students who were missionaries in China, and he strongly endorsed their work.[40][41]

Civil War and the Gilded Age: 1861–1897

[edit]American Civil War

[edit]Every nation was officially neutral throughout the American Civil War, and none recognized the Confederacy. That marked a major diplomatic achievement for Secretary Seward and the Lincoln Administration. France, under Napoleon III, had invaded Mexico and installed a puppet regime; it hoped to negate American influence. France therefore encouraged Britain in a policy of mediation suggesting that both would recognize the Confederacy.[42] Washington repeatedly warned that meant war. The British textile industry depended on cotton from the South, but it had stocks to keep the mills operating for a year and in any case the industrialists and workers carried little weight in British politics. A war would cut off vital shipments of American food, wreak havoc on the British merchant fleet, and cause the immediate loss of Canada. Britain therefore refused to go along with French schemes.[43]

Washington's policy was deficient in 1861 in terms of appealing to European public opinion. Diplomats had to explain that United States was not committed to the ending of slavery, but instead they repeated legalistic arguments about the unconstitutionality of secession. Confederate spokesman, on the other hand, were much more successful by ignoring slavery and instead focusing on their struggle for liberty, their commitment to free trade, and the essential role of cotton in the European economy. In addition, the European aristocracy (the dominant factor in every major country) was "absolutely gleeful in pronouncing the American debacle as proof that the entire experiment in popular government had failed. European government leaders welcomed the fragmentation of the ascendant American Republic."[44]

Elite opinion in Britain tended to favor the Confederacy, while public opinion tended to favor the United States. Large-scale trade continued in both directions with the United States, with the Americans shipping grain to Britain while Britain sent manufactured items and munitions. Immigration continued into the United States. British trade with the Confederacy was limited, with a trickle of cotton going to Britain and hundreds of thousands of munitions slipped in by numerous small blockade runners.[45] The Confederate strategy for securing independence was largely based on the hope of military intervention by Britain and France, but Confederate diplomacy proved inept. With the announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, it became a war against slavery that most British supported.[46]

A serious diplomatic dispute erupted over the "Trent Affair" in late 1861, when the American navy seized Confederate diplomats from a British ship. Public opinion in the Union called for war against Britain, but Lincoln gave in and sent back the diplomats his Navy had illegally seized.[47]

British financiers built and operated most of the blockade runners, spending hundreds of millions of pounds on them. They were staffed by sailors and officers on leave from the Royal Navy. When the U.S. Navy captured one of the fast blockade runners, it sold the ship and cargo as prize money for the American sailors, then released the crew. During the war, British blockade runners delivered the Confederacy 60% of its weapons, 1/3 of the lead for its bullets, 3/4 of ingredients for its powder, and most of the cloth for its uniforms;[45] some historians have claimed this lengthened the Civil War by two years.[48]

The American diplomatic mission headed by Minister Charles Francis Adams, Sr. proved much more successful than the Confederate missions, which were never officially recognized.[49] Historian Don Doyle has argued that the Union victory had a major impact on the course of world history.[50] The Union victory energized popular democratic forces. A Confederate victory, on the other hand, would have meant a new birth of slavery, not freedom. Historian Fergus Bordewich, following Doyle, argues that:

- The North's victory decisively proved the durability of democratic government. Confederate independence, on the other hand, would have established An American model for reactionary politics and race-based repression that would likely have cast an international shadow into the twentieth century and perhaps beyond."[51]

Alaska and Canada

[edit]

Secretary of State Seward was an enthusiastic expansionist, but he had minimal support in Congress. In 1867, Russia, fearing a possible war with Great Britain, decided it would quickly lose its Alaska colony in a war, and decided to sell it to the United States for $7.2 million. The bargain was much too good to pass up, especially since it gave the Americans a major presence in the North Pacific and blocked the British from expanding there. Public opinion was generally supportive, despite much humor about the folly of purchasing a giant "Polar bear garden." American soldiers replace the Russians, and the Russian merchants involved in the fur trade all left. However some Russian Orthodox priests remained as missionaries among the Alaska natives. Alaska attracted almost no attention until the 1890s, when gold was discovered in the neighboring Yukon district of Canada, and the easiest way for miners to get there was through Alaska. In addition gold was found in Alaska itself.[52]

Relations with Britain (and its Canadian colonies) were tense. British officials were negligent in allowing Confederates to raid Vermont in November 1864. For Washington, a high-priority long-term issue was warships built by British shipyards and outfitted for the Confederacy, especially the CSS Alabama, over vehement protests from American diplomats. After 1865 Washington at the minimum demanded the British to pay for the damages done by the warships known as the Alabama Claims. But the maximum demands were much higher. Powerful Republican Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts argued that British blockade runners were responsible for sustaining the Confederate war effort by smuggling weapons into Southern ports, thus prolonging the Civil War by two years.[53] He argued that Britain should pay the entire expense of those two years and the unspoken assumption was that Washington would take parts of Canada in exchange for that debt; British Columbia, Red River (Manitoba), and Nova Scotia seemed possible. London naturally refused.[54]

Washington looked the other way when Irish activists known as Fenians tried and failed in a small invasion of Canada in 1866 and 1870-1871.[55] Canada could never be defended so the British decided to cut their losses and eliminate the risk of a conflict with the U.S. The first ministry of William Gladstone withdrew from all its historic military and political responsibilities in North America. It brought home its troops (keeping Halifax as an Atlantic naval base), and turned responsibility over to the locals. That made it wise to unify the separate Canadian colonies into a self-governing confederation named the Dominion of Canada.[56]

Negotiations for the Alabama Claims dragged on for years until Hamilton Fish became Secretary of State under President Ulysses S. Grant in 1869. Fish ranks with Webster as the leading American diplomat of the 19th century, and he worked out an amicable solution with Britain. The controversy was peacefully resolved in 1872 by an international arbitration tribunal, in which the U.S. received $15.5 million from Britain for damages caused by British-built Confederate warships.[57][58]

James G. Blaine

[edit]James G. Blaine, a leading Republican (and its losing candidate for president in 1884) was a highly innovative Secretary of State in the 1880s. By 1881, Blaine had completely abandoned his high-tariff Protectionism and used his position as Secretary of State to promote freer trade, especially within the Western Hemisphere.[59] His reasons were twofold: firstly, Blaine's wariness of British influence in the Americas was undiminished, and he saw increased trade with Latin America as the best way to keep Britain from dominating the region. Secondly, he believed that by encouraging exports, he could increase American prosperity. President Garfield agreed with his Secretary of State's vision and Blaine called for a Pan-American conference in 1882 to mediate disputes among the Latin American nations and to serve as a forum for talks on increasing trade. At the same time, Blaine hoped to negotiate a peace in the War of the Pacific then being fought by Bolivia, Chile, and Peru. Blaine sought to expand American influence in other areas, calling for renegotiation of the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty to allow the United States to construct a canal through Panama without British involvement, as well as attempting to reduce British involvement in the strategically located Kingdom of Hawaii.[60] His plans for the United States' involvement in the world stretched even beyond the Western Hemisphere, as he sought commercial treaties with Korea and Madagascar. By 1882, however, a new Secretary was reversing Blaine's Latin American initiatives.[61]

Serving again as Secretary of State under Benjamin Harrison, Blaine worked for closer ties with the Kingdom of Hawaii, and sponsored a program to bring together all the independent nations of the Western Hemisphere in what became the Pan-American Union.[62] Before 1892, senior diplomats from the United States to other countries, and from them to the U.S., were called "ministers." In 1892 four major European countries (Britain, France, Germany, and Italy) raised the title of their chief diplomat to the US to "ambassador"; the US reciprocated in 1893.[63]

Hawaii

[edit]While European powers, and Japan, engaged in an intense scramble for colonial possessions in Africa and Asia, the United States stood aloof. This began to change in 1893. In the early 1880s, the United States had only a small army stationed at scattered Western forts, and an old fashioned wooden navy. By 1890 the U.S. began investment in new naval technology including steam-powered battleships with powerful armaments and steel decking. Naval planners led by Alfred Thayer Mahan used the success of the British Royal Navy to explore the opportunity for American naval power.[64]

In 1893 the business community in Kingdom of Hawaii overthrew the Queen for trying to become an absolute monarch. Fearing a takeover by Japan, the new government sought annexation by the United States. Harrison, a Republican, was in favor and forwarded the proposal to the Senate for approval. But the newly elected President Cleveland, a Democrat opposed to expansionism, withdrew the proposed annexation. Hawaii instead formed an independent Republic of Hawaii. Unexpectedly foreign-policy became a central concern of American politics. Historian Henry Graff says that at first, "Public opinion at home seemed to indicate acquiescence....Unmistakably, the sentiment at home was maturing with immense force for the United States to join the great powers of the world in a quest for overseas colonies."[65]

Cleveland, on taking office in March 1893, rescinded the annexation proposal. His biographer Alyn Brodsky argues he was deeply adverse to an immoral action against the little kingdom which no longer existed.[66]

Cleveland tried to mobilize support from Southern Democrats to fight the treaty. He sent former Georgia Congressman James H. Blount as a special representative to Hawaii to investigate and provide a solution. Blount was well known for his opposition to imperialism. Blount was also a leader in the white supremacy movement that was ending the right to vote by southern Blacks.. Some observers speculated he would support annexation on grounds of the inability of the Asiatics to govern themselves. Instead, Blount opposed imperialism, and called for the US military to restore of Queen Liliʻuokalani. He argued that the Hawaii natives should be allowed to continue their "Asiatic ways."[67] Cleveland wanted to restore the Queen, but when she promised to execute the governing leaders in Hawaii he drew back, The Republic of Hawaii was recognized by the powers, and Japan was interested in seizing it;,[68][69]

Trouble with Great Britain

[edit]Closer to home, Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine that not only prohibited new European colonies, but also declared an American national interest in any matter of substance within the hemisphere.[70] When Britain and Venezuela disagreed over the boundary between Venezuela and the colony of British Guiana, Cleveland and Secretary of State Richard Olney protested.[71] British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and his ambassador to Washington, Julian Pauncefote, misjudged how important the dispute was to Washington, especially to the Irish Catholic element. It strongly opposed to British policy in Ireland, and comprised a powerful bloc inside the Democratic Party. London prolonged the crisis before accepting Washington's demand for arbitration.[72][73] An international tribunal in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[74] By standing with a small Latin American nation against the encroachment of the greatest colonial power, Cleveland improved relations with Latin America. At the same time, the cordial manner in which the arbitration was conducted also made for good relations with Britain and encouraged several of the major powers to consider arbitration as a solution to their controversies.[75]

Emergence as a Great Power: 1897–1913

[edit]Foreign policy suddenly became a major issue in national affairs after 1895.[76] Until 1898 American foreign policy was simple: to fulfill the country's manifest destiny and to remain free of entanglements overseas.[77]

International issues such as war, imperialism, and the national role in world affairs played a role in the 1900 presidential election.[78]

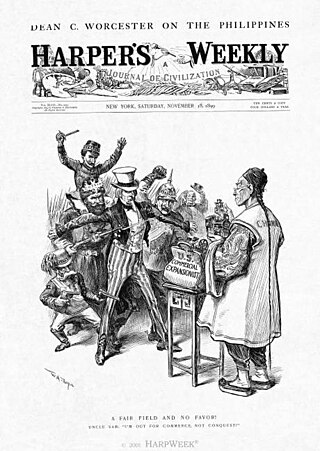

Expansionists triumphant

[edit]A vigorous nationwide anti-expansionist movement, organized as the American Anti-Imperialist League, emerged that listened to Cleveland and Carl Schurz, as well as Democratic leader William Jennings Bryan, industrialist Andrew Carnegie, author Mark Twain and sociologist William Graham Sumner, and many prominent intellectuals and politicians who came of age in the Civil War.[79] The anti-imperialists opposed expansion, believing that imperialism violated the fundamental principle that just republican government must derive from "consent of the governed." The League argued that such activity would necessitate the abandonment of American ideals of self-government and non-intervention—ideals expressed in the Declaration of Independence, George Washington's Farewell Address and Lincoln's Gettysburg Address.[80]

Despite the efforts of the Cleveland and others, Secretary of State John Hay, naval strategist Alfred T. Mahan, Republican congressman Henry Cabot Lodge, Secretary of War Elihu Root, and young politician Theodore Roosevelt rallied expansionists. They had vigorous support from newspaper publishers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, whipping up popular excitement. Mahan and Roosevelt designed a global strategy calling for a competitive modern navy, Pacific bases, an isthmian canal through Nicaragua or Panama, and, above all, an assertive role for America as the largest industrial power.[81]

President McKinley's position was that Hawaii could never survive on its own. It would quickly be gobbled up by Japan—already a fourth of the islands' population was Japanese. Japan would then dominate the Pacific and undermine American hopes for large-scale trade with Asia.[82] While the Democrats could block a treaty in the Senate by denying it a two thirds majority, McKinley annexed Hawaii through a joint resolution, which required only a majority vote in each house. Hawaii became a territory in 1898 with full U.S. citizenship for its residents. It became the 50th state in 1959.[83]

Open Door policy toward China

[edit]The Open Door was a principle of free trade advocated by the United States towards China from 1850-1949. It called for equal treatment of foreign nationals and firms, as outlined in the Open Door notes issued in 1900 in cooperation with London. The idea was that all nations could gain access to the China market on equal, nonviolent terms, as opposed to China being divided into domains each controlled by a foreign state.[84] Washington refused to accept any alteration in Asia that impinged upon China's territorial integrity or competitive trade, as seen in Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan's response to Japan's demands. The Open Door was included in the Lansing–Ishii Agreement and internationalized in the Nine-Power Treaty. Views on the Open Door range from it being a cover for economic imperialism to an example of self-fulfilling moral exceptionalism or enlightened self-interest in American foreign policy.[85]

Foreign-policy expertise

[edit]Foreign-policy expertise in America in the 1890s was in limited supply. The State Department had a cadre of diplomats who rotated around, but the most senior positions were political patronage appointments. The holders sometimes acquired a limited expertise, but the overall pool was shallow. At the level of presidential candidate and secretary of state, the entire half-century after 1850 showed minimal expertise or interest, with the exception of William Seward in the 1860s, and James G. Blaine in the 1880s. After 1900, experience deepened in the State Department, and at the very top level, Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson, Hoover and their secretaries of state comprised a remarkable group with deep knowledge of international affairs. American elections rarely featured serious discussion of foreign-policy, with a few exceptions such as 1910, 1916, 1920 and 1940.[86]

Anytime a crisis erupted, the major newspapers and magazines commented at length on what Washington should do. The media relied primarily on a small number of foreign-policy experts based in New York City and Boston. Newspapers elsewhere copied their reports and editorials. Sometimes the regional media had a local cadre of experts who could comment on Europe, but they rarely had anyone who knew much about Latin America or Asia. Conceptually, the media experts relied on American traditions – what would Washington or Jefferson or Lincoln have done in this crisis?-- And what impact it might have on current business conditions. Social Darwinist ideas were broad, but they seldom shaped foreign-policy views. The psychic crisis that some historians discovered in the 1890s had very little impact. Travel in Europe, and close reading of British media were the chief sources for media experts.[87] Religious magazines had a cadre of returned missionaries who were helpful, and ethnic groups, especially the Irish and the Germans and the Jews had their own national experts whose views appeared in their own periodicals.[88]

Cuba and Spain

[edit]

In the mid 1890s, American public opinion denounced the Spanish repression of the Cuban independence movement as brutal and unacceptable. The U.S. increased pressure and was dissatisfied with Spanish responses. When the American battleship the USS Maine exploded for undetermined reasons in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, on 15 February 1898, the issue became overwhelming and McKinley could not resist the demands for immediate action. Most Democrats and many Republicans demanded war to liberate Cuba. Almost simultaneously the two countries declared war. (Every other country was neutral.) The U.S. easily won the one-sided four-month-long Spanish–American War from April through July. In the Treaty of Paris, the U.S. took over the last remnants of the Spanish Empire, notably Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam. It marked America's transition from a regional to a global power. Cuba was given independence under American supervision.[89] However the permanent status of the Philippines became a heated political issue. Democrats, led by William Jennings Bryan, had strongly supported the war but now they strongly opposed annexation.[90] McKinley was reelected and annexation was decided.[91]

The U.S. Navy emerged as a major naval power thanks to modernization programs begun in the 1880s and adopted the sea power theories of Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan. The Army remained small but was reorganized in the Roosevelt Administration along modern lines and no longer focused on scattered forts in the West. The Philippine–American War was a short operation to suppress insurgents and ensure U.S. control of the islands; by 1907, however, interest in the Philippines as an entry to Asia faded in favor of the Panama Canal, and American foreign policy centered on the Caribbean. The 1904 Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which proclaimed a right for the United States to intervene to stabilize weak states in the Americas, further weakened European influence in Latin America and further established U.S. regional hegemony.[92]

The outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 ended a half century of peaceful borders and brought escalating tensions, as revolutionaries threatened American business interests and hundreds of thousands of refugees fled north. President Woodrow Wilson tried using military intervention to stabilize Mexico but that failed. After Mexico in 1917 rejected Germany's invitation in the Zimmermann Telegram to join in war against the U.S., relations stabilized and there were no more interventions in Mexico. Military interventions did occur in other small countries like Nicaragua, but were ended by the Good Neighbor policy announced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, which allowed for American recognition of and friendship with dictatorships.[93]

Wilson and World War I

[edit]From neutrality to war to end all wars: 1914–1917

[edit]American foreign policy was largely determined by President Woodrow Wilson, who had shown little interest in foreign affairs before entering the White House in 1913. His chief advisor was "Colonel" Edward House, who was sent on many top-level missions. Wilson's foreign policy was based on an idealistic approach to liberal internationalism that sharply contrasted with the realist conservative nationalism of Taft, Roosevelt, and William McKinley.[94] Since 1900, the consensus of Democrats had, according to Arthur Link:

- consistently condemned militarism, imperialism, and interventionism in foreign policy. They instead advocated world involvement along liberal-internationalist lines. Wilson's appointment of William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State indicated a new departure, for Bryan had long been the leading opponent of imperialism and militarism and a pioneer in the world peace movement.[95]

The United States intervened militarily in many Latin American nations to stabilize the governments, impose democracy, and protect commerce. In the case of Mexico it was a response to attacks on Americans. Wilson landed U.S. troops in Mexico in 1914; in Haiti in 1915; in the Dominican Republic in 1916; in Mexico several additional times; in Cuba in 1917; and in Panama in 1918. Also, for most of the Wilson administration, the U.S. military occupied Nicaragua, installing an honest president.[96]

With the outbreak of war in 1914, the United States declared neutrality and worked to broker a peace. It insisted on its neutral rights, which included allowing private corporations and banks to sell or loan money to either side. With the British blockade, there were almost no sales or loans to Germany, only to the Allies. The widely publicized atrocities in Germany shocked American public opinion. Neutrality was supported by Irish-Americans, who were hostile Britain, by German Americans who wanted to remain neutral, and by women and the churches. It was supported by the more educated upscale WASP element, led by Theodore Roosevelt. Wilson insisted on neutrality, denouncing both Allied and German violations, especially those German violations in which American civilians were killed. The German U-boat torpedoed the RMS Lusitania in 1915. It sank in 20 minutes, killing 128 American civilians and over 1,000 Britons. It was against the laws of war to sink any passenger ship without allowing the passengers to reach the life boats. American opinion turned strongly against Germany as a bloodthirsty threat to civilization.[97] Germany apologized and repeatedly promised to stop attacks by its U-boats, but reversed course in early 1917 when it saw the opportunity to strangle Britain by unrestricted submarine warfare. It also made overtures to Mexico, in the Zimmermann Telegram, hoping to divert American military attention to south of the border. The German decision was not made or approved by the civilian government in Berlin, but by the military commanders and the Kaiser. They realized it meant war with the United States, but hoped to weaken the British by cutting off its imports, and strike a winning blow with German troops transferred from the Eastern front, where Russia had surrendered. Following the repeated sinking of American merchant ships in early 1917, Wilson asked Congress and obtained a declaration of war in April 1917. He neutralized the antiwar element by arguing this was a war with the main goal of ending aggressive militarism and indeed ending all wars. During the war the U.S. was not officially tied to the Allies by treaty, but military cooperation meant that the American contribution became significant in mid-1918. After the failure of the German spring offensive, as fresh American troops arrived in France at 10,000 a day, the Germans were in a hopeless position, and thus surrendered. Coupled with Wilson's Fourteen Points in January 1918, the U.S. now had the initiative on the military, diplomatic and public relations fronts. Wilsonianism—Wilson's ideals—had become the hope of the world, including the civilian population Germany itself.[98]

Involvement in Russia

[edit]The U.S. joined with several Allies to intervene in Russia in 1918-1919. The U.S. military was strongly opposed, but President Wilson reluctantly ordered the action. The British had taken the lead and were emphatically urging American help. Wilson feared that if he said no he would undermine his primary goal of creating a League of Nations with full British support.[99] The main British goals were to help the Czechoslovak Legion re-establish the Eastern Front. At times between 1918 and 1920 the Czechoslovak Legion controlled the entire Trans-Siberian Railway and several major cities in Siberia. American Marines and sailors were deployed to Vladivostok and Murmansk from April 1918 to December 1919. The main American mission was to guard large munitions dumps. Americans also served alongside Japanese soldiers in Vladivostok in far eastern Siberia from 1918 to 1920. They were involved in little fighting; most of the losses came from disease and cold.[100][101] The U.S. and Allied powers ended operations by early 1920, though Japan continued until 1922. For Soviet Communists, the operation was proof that Western powers were keen to destroy the Soviet government if they had the opportunity to do so.[102]

Winning the war and fighting for peace

[edit]

At the peace conference at Versailles, Wilson tried with mixed success to enact his Fourteen Points. He was forced to accept British, French and Italian demands for financial revenge: Germany would be made to pay reparations that amounted to the total cost of the war for the Allies and admit guilt in humiliating fashion. It was a humiliating punishment for Germany which subsequent commentators thought was too harsh and unfair. Wilson succeeded in obtaining his main goal, a League of Nations that would hopefully resolve all future conflicts before they caused another major war.[103] Wilson, however, refused to consult with Republicans, who took control of Congress after the 1918 elections and which demanded revisions protecting the right of Congress to declare war. Wilson refused to compromise with the majority party in Congress, or even bring any leading Republican to the peace conference. His personal enemy, Henry Cabot Lodge, now controlled the Senate. Lodge did support the league of Nations, but wanted provisions that would insist that only Congress could declare war on behalf of the United States. Wilson was largely successful in designing the new League of Nations, declaring it would be:

- a great charter for a new order of affairs. There is ground here for deep satisfaction, universal reassurance, and confident hope.[104]

The League did go into operation, but the United States never joined. With a two-thirds vote needed, the Senate did not ratify either the original Treaty or its Republican version. Washington made separate peace treaties with the different European nations. Nevertheless, Wilson's idealism and call for self-determination of all nations had an effect on nationalism across the globe, while at home his idealistic vision, called "Wilsonianism" of spreading democracy and peace under American auspices had a profound influence on much of American foreign policy ever since.[105]

Debate on Wilson's role

[edit]Perhaps the harshest attack on Wilson's diplomacy comes from Stanford historian Thomas A. Bailey in two books that remain heavily cited by scholars, Woodrow Wilson and the Lost Peace (1944) and Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1945), Bailey:

- contended that Wilson's wartime isolationism, as well as his peace proposals at war's end, were seriously flawed. Highlighting the fact that American delegates encountered staunch opposition to Wilson's proposed League of Nations, Bailey concluded that the president and his diplomatic staff essentially sold out, compromising important American ideals to secure mere fragments of Wilson's progressive vision. Hence, while Bailey primarily targeted President Wilson in these critiques, others, including House, did not emerge unscathed.[106]

Scot Bruce argues that:

- More recently, prominent historians such as Thomas J. Knock, Arthur Walworth, and John Milton Cooper, among others, shied away from condemning Wilson and his peacemakers for extensive diplomatic failures in Paris. Instead, they framed Wilsonian progressivism, articulated through the League of Nations, as a comparatively enlightened framework tragically undermined by British and French machinations at the peace conference. ... Historian Margaret MacMillan, continued this analytical trend in her prize-winning book, Paris, 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (2001), which characterized Wilson as the frustrated idealist, unable to secure his progressive vision due to opposition from old-guard imperialists in his midst. While realists like Lloyd E. Ambrosius questioned the merits of defining Wilsonian progressivism too idealistically, the idea has persisted that well-intentioned U.S. delegates encountered staunch opposition to Wilson's proposals in Paris, and therefore compromised under pressure. Even the great Wilson scholar, Arthur S. Link, subscribed to a version of this narrative.[107]

Three approaches: Wilsonian idealism, realism, revisionism

[edit]Historians and political analyst have been largely Wilsonian in their approach to American diplomatic history, according to Lloyd Ambrosius. But there are alternative schools of thought as well. Ambrosius argues that Wilsonianism is based on national self-determination and democracy; open door globalization based on open markets for trade and finance; collective security as typified by the Wilson's idea of the League of Nations as well as NATO; and a hope bordering on a promise of future peace and progress.[108] Realism is the first alternative school, based on the outlook and policies of Theodore Roosevelt, and represented most famously by George Kennan, Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon. Democracy for realists was a low priority—they would eagerly work with dictators who supported American positions. A third approach emerged out of the New Left in the 1960s, led by William Appleman Williams and the "Wisconsin School". It is called "Revisionism" and argues that selfish economic motivations, not idealism or realism, motivated Wilsonianism. Ambrosius argues that historians generally agree that Wilsonianism was the main intellectual force in battling the Nazis in 1945 and the Soviet communists in 1989. It seemed to be the dominant factor in world affairs by 1989.[109] Wilsonians were shocked when the Chinese Communists rejected democracy in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, and when Putin rejected it for Russia.[110]

Wilsonians were dismayed when George W. Bush's initiative to bring democracy to the Middle East after 9/11 failed.[111] It produced not an Arab Spring, but instead antidemocratic results most famously in Egypt, Iraq. Syria, and Afghanistan.[112][113]

Interwar years: 1921–1933

[edit]In the 1920s, American policy was an active involvement in international affairs, while ignoring the League of Nations, setting up numerous diplomatic ventures, and using the enormous financial power of the United States to dictate major diplomatic questions in Europe. There were large-scale humanitarian food aid missions during the war in Belgium, and after it in Germany and Russia, led by Herbert C. Hoover.[114] There was also a major aid to Japan after the 1923 earthquake.[115]

The Republican presidents, Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover, avoided any political alliances with anyone else. They operated large-scale American intervention in issues of reparations and disarmament, with little contact with the League of Nations. Historian Jerald Combs reports their administrations in no way returned to 19th-century isolationism. The key Republican leaders:

- including Elihu Root, Charles Evans Hughes, and Hoover himself, were Progressives who accepted much of Wilson's internationalism.... They did seek to use American political influence and economic power to goad European governments to moderate the Versailles peace terms, induce the Europeans to settle their quarrels peacefully, secure disarmament agreements, and strengthen the European capitalist economies to provide prosperity for them and their American trading partners.[116]

Rejection of the World Court

[edit]The U.S, played a major role in setting up the "Permanent Court of International Justice", known as the World Court.[117] Presidents Wilson, Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover supported membership but were unable to get a 2/3 majority in the Senate for a treaty. Roosevelt also supported membership, but he did not make it a high priority. Opposition was intense on the issue of losing sovereignty, led by the Hearst newspapers and Father Coughlin. The U.S. never joined.[118][119][120] The World Court was replaced by the International Court of Justice in 1945. However, the Connally Amendment of 1944 reserved the right of the United States to refuse to abide by its decisions. Margaret A. Rague, argues this reduced the strength of the Court, discredited America's image as a proponent of international law, and exemplified the problems created by vesting a reservation power in the Senate.[121][122]

Naval disarmament

[edit]

The Washington Naval Conference (its formal title was " International Conference on Naval Limitation") was the most successful diplomatic venture the 1920s. Promoted by Senator William E. Borah, Republican of Idaho, it had the support of the Harding Administration. It was held in Washington, and was chaired by Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes from 12 November 1921 to 6 February 1922. Conducted outside the auspice of the League of Nations, it was attended by nine nations—the United States, Japan, China, France, Great Britain, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, and Portugal[123] The USSR and Germany were not invited. It focused on resolving misunderstandings or conflicts regarding interests in the Pacific Ocean and East Asia. The main achievement was a series of naval disarmament agreements agreed to by all the participants, that lasted for a decade. It resulted in three major treaties: Four-Power Treaty, Five-Power Treaty (the Washington Naval Treaty), the Nine-Power Treaty, and a number of smaller agreements. These treaties preserved peace during the 1920s but were not renewed, as the world scene turned increasingly negative after 1930.[124]

Dawes Plan and Young Plan

[edit]The Dawes Plan was an attempt to find a solution to the crisis of World War I reparations, in which France was demanding that Germany pay strictly according to the London Schedule of Payments. When Germany was declared in default, French and Belgian troops occupied the key industrial Ruhr district in January 1923. Germany responded with a policy of passive resistance and supported the idled workers by printing additional money, spurring the onset of hyperinflation.[125] The immediate crisis was solved by the 1924 Dawes Plan, an international effort chaired by the American banker Charles G. Dawes. It set up a staggered schedule for Germany's payment of war reparations, provided for a large loan to stabilise the German currency and ended the occupation of the Ruhr.[126] It resulted in a brief period of economic recovery in the second half of the 1920s.[127] By 1928 Germany, France and the United States were all interested in a new payment plan, leading to the 1929 Young Plan, named after its chairman, the American Owen D. Young. It established German reparations at 112 billion marks (US$26.3 billion)[128] and created a schedule that would see Germany complete payments by 1988. It was also meant to allow France and Britain to repay the war loans owed to the United States using German reparations. With the onset of the Great Depression, however, the Young Plan crumbled.[129] In 1932 the Hoover administration convinced 15 nations to sign on to suspending reparations for a year, and after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, no additional payments were made for 20 years. Between 1919 and 1932, Germany paid less than 21 billion marks in reparations. After 1953, West Germany paid the entire remaining balance.[130]

Mexico

[edit]Since the turmoil of the Mexican revolution had died down, the Harding administration was prepared to normalize relations with Mexico. Between 1911 and 1920, American imports from Mexico increased from $57,000,000 to $179,000,000 and exports from $61,000,000 to $208,000,000. Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover took the lead in order to promote trade and investments other than in oil and land, which had long dominated bilateral economic ties. President Álvaro Obregón assured Americans that they would be protected in Mexico, and Mexico was granted recognition in 1923.[131] A major crisis erupted in the mid-1930s when the Mexican government expropriated millions of acres of land from hundreds of American property owners as part of President Lázaro Cárdenas's land redistribution program. No compensation was provided to the American owners.[132] The emerging threat of the Second World War forced the United States to agree to a compromise solution. The US negotiated an agreement with President Manuel Avila Camacho that amounted to a military alliance.[133]

Intervention ends in Latin America

[edit]Small-scale military interventions continued after 1921 as the Banana Wars tapered off. The Hoover administration began a goodwill policy and withdrew all military forces.[134] President Roosevelt announced the "Good Neighbor Policy" by which the United States would no longer intervene to promote good government, but would accept whatever governments were locally chosen. His Secretary of State Cordell Hull endorsed article 8 of the 1933 Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States; it provides that "no state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another".[135]

Roosevelt, World War II, and its aftermath: 1933–1947

[edit]Spanish Civil War: 1936–1939

[edit]In the 1930s, the United States entered the period of deep isolationism, rejecting international conferences, and focusing mostly on reciprocal tariff agreements with smaller countries of Latin America.[citation needed]

When the Spanish Civil War erupted in 1936, the United States remained neutral and banned arms sales to either side. This was in line with both American neutrality policies, and with a Europe-wide agreement to not sell arms for use in the Spanish war lest it escalate into a world war. Congress endorsed the embargo by a near-unanimous vote. Only armaments were embargoed; American companies could sell oil and supplies to both sides of the fight. Roosevelt quietly favored the left-wing Republican (or "Loyalist") government, but intense pressure by American Catholics forced him to maintain a policy of neutrality. The Catholics were outraged by the systematic torture, rape and execution of priests, bishops, and nuns by anarchist elements of the Loyalist coalition. This successful pressure on Roosevelt was one of the handful of foreign policy successes notched by Catholic pressures on the White House in the 20th century.[136]

Germany and Italy provided munitions, and air support, and troops to the Nationalists, led by Francisco Franco. The Soviet Union provided aid to the Loyalist government, and mobilized thousands of volunteers to fight, including several hundred from the United States in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. All along the Spanish military forces supported the nationalists, and they steadily pushed the government forces back. By 1938, however, Roosevelt was planning to secretly send American warplanes through France to the desperate Loyalists. His senior diplomats warned that this would worsen the European crisis, so Roosevelt desisted.[137]

Adolf Hitler and Franco mutually disliked one another, and Franco repeatedly manipulated Hitler for his own benefit during World War II. Franco sheltered Jewish refugees escaping through France and never turned over the Spanish Jews to Nazi Germany as requested, and when during the Second World War the Blue Division was dispatched to help the Germans, it was forbidden to fight against the Western Allies, and was limited only to fighting the Soviets.[138]

Coming of War: 1937–1941

[edit]President Roosevelt tried to avoid repeating what he saw as Woodrow Wilson's mistakes in World War I.[139] He often made exactly the opposite decision. Wilson called for neutrality in thought and deed, while Roosevelt made it clear his administration strongly favored Britain and China. Unlike the loans in World War I, the United States made large-scale grants of military and economic aid to the Allies through Lend-Lease, with little expectation of repayment. Wilson did not greatly expand war production before the declaration of war; Roosevelt did. Wilson waited for the declaration to begin a draft; Roosevelt started one in 1940. Wilson never made the United States an official ally but Roosevelt did. Wilson never met with the top Allied leaders but Roosevelt did. Wilson proclaimed independent policy, as seen in the 14 Points, while Roosevelt always had a collaborative policy with the Allies. In 1917, the United States declared war on Germany; in 1941, Roosevelt waited until the enemy attacked at Pearl Harbor. Wilson refused to collaborate with the Republicans; Roosevelt named leading Republicans to head the War Department and the Navy Department. Wilson let General John J. Pershing make the major military decisions; Roosevelt made the major decisions in his war including the "Europe first" strategy. He rejected the idea of an armistice and demanded unconditional surrender. Roosevelt often mentioned his role in the Wilson administration, but added that he had profited more from Wilson's errors than from his successes.[140][141][142]

Pearl Harbor was unpredictable

[edit]Political scientist Roberta Wohlstetter explores why all American intelligence agencies failed to predict the attack on Pearl Harbor. The basic reason was that the Japanese plans were a very closely held secret. The attack fleet kept radio silence and was not spotted by anyone en route to Hawaii. There were air patrols over Hawaii, but they were too few and too ineffective to scan a vast ocean. Japan Navy spread false information—using fake radio signals—to indicate the main fleet was in Japanese waters, and suggested their main threat was north toward Russia. The U.S. had MAGIC, which successfully cracked the Japanese diplomatic code. However, the Japanese Foreign Ministry and its diplomats were deliberately never told about the upcoming attack, so American intelligence was wasting its time trying to discover secrets through MAGIC. American intelligence expected attacks against British and Dutch possessions, and were looking for those clues. At Pearl Harbor, they focused on predicting local sabotage. There was no overall American intelligence center until the formation in 1942 of the Office of Strategic Services. It was the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In 1941 there was no coordination of the information coming in from the Army, Navy, and State department as well as from the British and Dutch allies. The system of notification was also flawed, and what the sender thought was an urgent message did not appear urgent to the recipient. After the attack, congressional investigators identified and linked together all sorts of small little signals pointing to an attack, while they discarded signals pointing in other directions. Even in hindsight there was so much confusion, noise, and poor coordination that Wohlstetter concludes no accurate predictions of the attack on Pearl Harbor was at all likely before December 7.[143][144]

World War II

[edit]The same pattern which emerged with the first world war continued with the second: warring European powers, blockades, official U.S. neutrality but this time President Roosevelt tried to avoid all of Wilson's mistakes. American policy substantially favored Britain and its allies, and the U.S. getting caught up in the war. Unlike the loans in World War I, the United States made large-scale grants of military and economic aid to the Allies through Lend-Lease. Industries greatly expanded to produce war materials. The United States officially entered World War II against Germany, Japan, and Italy in December 1941, following the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. This time the U.S. was a full-fledged member of the Allies of World War II, not just an "associate" as in the first war. During the war, the U.S. conducted military operations on both the Atlantic and Pacific fronts. After the war and devastation of its European and Asian rivals, the United States found itself in a uniquely powerful position due to its enormous economic and military power .[145]

The major diplomatic decisions, especially relations with Britain, the Soviet Union, France and China, were handled in the White House by President Roosevelt and his top aide Harry Hopkins.[146][147] Secretary of State Cordell Hull handled minor routine affairs.[148] The one State Department official Roosevelt depended upon was strategist Sumner Welles, whom Hull drove out of office in 1943.[149]

Postwar peace

[edit]

After 1945, the isolationist pattern that characterized the inter-war period had ended for good. Roosevelt policy supported a new international organization that would be much more effective than the old League of Nations, and avoid its flaws. He successfully sponsored the formation of the United Nations.[citation needed]

United Nations

[edit]The United States was a major force in establishing the United Nations in 1945, hosting a meeting of fifty nations in San Francisco. Avoiding the rancorous debates of 1919, where there was no veto, the US and the Soviet Union, as well as Britain, France and China, became permanent members of the Security Council with veto power. The idea of the U.N. was to promote world peace through consensus among nations, with boycotts, sanctions and even military power exercised by the Security Council. It depended on member governments for funds and had difficulty funding its budget. In 2009, its $5 billion budget was funded using a complex formula based on GDP; the U.S. contributed 20% in 2009. However, the United Nations' vision of peace soon became jeopardized as the international structure was rebalanced with the development and testing of nuclear weapons by major powers.[150]

Decolonization

[edit]Historian James Meriweather argues that American policy towards Africa was characterized by a middle road approach, which supported African independence but also reassured European colonial powers that their holdings could remain intact. Washington wanted the right type of African groups to lead newly independent states, which tended to be noncommunist and not especially democratic. Foundations and nongovernmental organizations influenced American policy towards Africa. They pressured state governments and private institutions to disinvest from African nations not ruled by the majority population. These efforts also helped change American policy towards South Africa, as seen with the passage of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.[151]

South in foreign policy

[edit]The South always had a strong, aggressive interest in foreign affairs, especially regarding expansion to the Southwest and the importance of foreign markets for Southern exports of cotton, tobacco and oil.[152] All the southern colonies supported the American Revolution, with Virginia taking a leading position. The South generally supported the War of 1812, in sharp distinction to the strong opposition in the Northeast. Southern Democrats took the lead and support of Texas annexation, and the war with Mexico.[153] Low tariff policy was a priority, with the partial exception of the sugar region of Louisiana. Throughout southern history, exports were the main foundation of the southern economy, starting with tobacco, rice and indigo in the colonial period. After 1800 cotton comprised the chief export of the United States . Confederates thought (mistakenly) that European need for cotton would require intervention to help the South, for “Cotton is King.”[154][155] Southerners calculated their need for international markets called for aggressive internationalist foreign policies.[156]

Woodrow Wilson had a strong base in the south for his foreign policy regarding World War I and the League of Nations.[157] In the late 1930s, Southern Conservative Democrats opposed the domestic policies of the New Deal but strongly supported Franklin Roosevelt's internationalist foreign policy.[158] Historians have given various explanations for this characteristic. The region had a strong military tradition.[159] For example, General George Marshall, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute is famous for the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe after World War II. Rather than pacifism, the South fostered chivalry and honor, pride in its fighting ability, and indifference to violence.[160] In the 1930s isolationism and America First attitudes were weakest in the South, and internationalism strongest there. Virginia Senator Carter Glass proclaimed in May, 1941: "Virginia has always been a leader in the vanguard of the fight for freedom. She is ready today as in the past to give virile leadership to the nation."[161] There were some dissenters from aggression such as J. William Fulbright, and Martin Luther King Jr. who opposed the Vietnam War of Lyndon Johnson (Texas) and Secretary of State Dean Rusk (Georgia), but that war was generally more popular in the South.[162]

Cold War: 1947–1991

[edit]

Truman and Eisenhower

[edit]From the late 1940s until 1991, world affairs were dominated by the Cold War, in which the U.S. and its allies faced the Soviet Union and its allies. There was no large-scale fighting but instead numerous regional wars as well as the ever-present threat of a catastrophic nuclear war.[163][164]

Before the Korean War started in 1950, the Truman Administration emphasized economic strengthening of non-Communist states, especially in Western Europe as well as Japan. In 1948 the United States enacted the Marshall Plan, which supplied Western Europe (including West Germany) with US$13 billion in reconstruction aid. Stalin vetoed any participation by East European nations. A similar program was operated by the United States to restore the Japanese economy. The U.S. actively sought allies, which it subsidized with military and economic "foreign aid", as well as diplomatic support. The main diplomatic initiative was the establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949, committing the United States to nuclear defense of Western Europe, which engaged in a military buildup under NATO's supervision. The result was peace in Europe, coupled with the fear of Soviet invasion and a reliance on American protection. By 1950 there was a large-scale buildup of American military strength, as called for in the top secret American strategy outlined in NSC 68 of 1950.[165]

In the 1950s, a number of other less successful regional alliances were developed by the United States, such as the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). Economic and propaganda warfare against the communist world was part of the American toolbox.[166] The United States operated a worldwide network of bases for its Army, Navy and Air Force, with large contingents stationed in Germany, Japan and South Korea.[167]

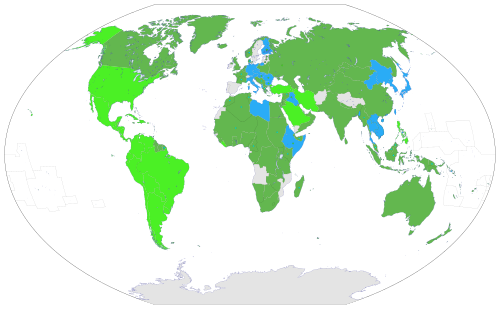

Most nations aligned with either the Western or Eastern Bloc, although splits between Soviet Union with both China and Albania over former's revisionism and de-Stalinization happening throughout 1960s, then China and Albania throughout 1970s, as the communist movement worldwide became divided. Some countries, such as India and Yugoslavia, attempted a non-aligned approach. Rejecting the rollback of communism by force because it risked nuclear war, Washington developed a new geopolitical strategic foreign policy called 'Containment' to oppose the spread of communism. The containment policy was developed by U.S. diplomat George Kennan in 1947. Kennan characterized the Soviet Union as an aggressive, anti-Western power that necessitated containment, a characterization which would shape US foreign policy for decades to come. The idea of containment was to match Soviet aggression with force wherever it occurred while not using nuclear weapons. The policy of containment created a bipolar, zero-sum world where the ideological conflicts between the Soviet Union and the United States dominated geopolitics. Due to the antagonism on both sides and each countries' search for security, a tense worldwide contest developed between the two states as the two nations' governments vied for global supremacy militarily, culturally, and influentially.[citation needed]

The Cold War was characterized by a lack of global wars but a persistence of regional proxy wars, often fought between client states and proxies of the United States and Soviet Union. The US also intervened in the affairs of other countries through a number of secret operations.[citation needed]

During the Cold War, the Containment policy seeking to stop Soviet expansion, involved the United States and its allies in the Korean War (1950–1953), a stalemate. Even longer and more disastrous was the Vietnam War (1963–75). Under Jimmy Carter, the U.S. and its Arab allies Succeeded in creating a Vietnamese -like disaster for the Soviet Union by supporting anti-Soviet Mujahideen forces in Afghanistan (Operation Cyclone).[168]

Kennedy and Johnson 1961–1969

[edit]

The Cold War reached its most dangerous point during the Kennedy administration in the Cuban Missile Crisis, a tense confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States over the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The crisis began on October 16, 1962, and lasted for thirteen days. It was the moment when the Cold War was closest to exploding into a devastating nuclear exchange between the two superpower nations. Kennedy decided not to invade or bomb Cuba but to institute a naval blockade of the island. The crisis ended in a compromise, with the Soviets removing their missiles publicly, and the United States secretly removing its nuclear missiles in Turkey. In Moscow, Communist leaders removed Nikita Khrushchev because of his reckless behavior.[169][additional citation(s) needed]

Vietnam and the Cold War are the two major issues that faced the Kennedy presidency. Historians disagree. However, there is general scholarly agreement that his presidency was successful on a number of lesser issues. Thomas Paterson finds that the Kennedy administration helped quiet the crisis over Laos; was suitably cautious about the Congo; liberalized trade; took the lead in humanitarianism especially with the Peace Corps; helped solve a nasty dispute between Indonesia and the Netherlands; achieve the Limited Test Man Treaty; created a new Arms Control and Disarmament Agency; defended Berlin; and strengthened European defenses. His willingness to negotiate with Khrushchev smoothed the Berlin crisis, and Kennedy's personal diplomacy earned him the respect of Third World leaders.[170][additional citation(s) needed]

On the two major issues, no consensus has been reached. Michael L. Krenn argues in 2017:

- Fifty-some years after his assassination, John F. Kennedy remains an enigma. Was he the brash and impulsive president who brought the world to the brink of World War III with the Cuban Missile Crisis? Or was he the brave challenger of the American military-industrial complex who would have prevented the Vietnam War? Various studies portray him as a Cold War liberal, or a liberal Cold Warrior, or come up with pithy phrases to summarize the man and his foreign policy.[171]