Histopathology of colorectal adenocarcinoma

The histopathology of colorectal cancer of the adenocarcinoma type involves analysis of tissue taken from a biopsy or surgery. A pathology report contains a description of the microscopical characteristics of the tumor tissue, including both tumor cells and how the tumor invades into healthy tissues and finally if the tumor appears to be completely removed. The most common form of colon cancer is adenocarcinoma, constituting between 95%[2] and 98%[3] of all cases of colorectal cancer. Other, rarer types include lymphoma, adenosquamous and squamous cell carcinoma. Some subtypes have been found to be more aggressive.[4]

Macroscopy

[edit]Cancers on the right side of the large intestine (ascending colon and cecum) tend to be exophytic, that is, the tumor grows outwards from one location in the bowel wall. This very rarely causes obstruction of feces, and presents with symptoms such as anemia. Left-sided tumors tend to be circumferential, and can obstruct the bowel lumen, much like a napkin ring, and results in thinner caliber stools.

-

Appearance of the inside of the colon showing one invasive colorectal carcinoma (the crater-like, reddish, irregularly shaped tumor)

-

Gross appearance of a colectomy specimen containing two adenomatous polyps (the brownish oval tumors above the labels, attached to the normal beige lining by a stalk) and one invasive colorectal carcinoma (the crater-like, reddish, irregularly shaped tumor located above the label)

-

Endoscopic image of colon cancer identified in sigmoid colon on screening colonoscopy in the setting of Crohn's disease

-

PET/CT of a staging exam of colon carcinoma. Besides the primary tumor a lot of lesions can be seen. On cursor position: lung nodule.

-

Fungating carcinoma of the colon

-

Edges and margins of an intestinal tumor

Microscopy

[edit]Adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumor, originating from superficial glandular epithelial cells lining the colon and rectum. It invades the wall, infiltrating the muscularis mucosae layer, the submucosa, and then the muscularis propria. Tumor cells describe irregular tubular structures, harboring pluristratification, multiple lumens, reduced stroma ("back to back" aspect). Sometimes, tumor cells are discohesive and secrete mucus, which invades the interstitium producing large pools of mucus. This occurs in mucinous adenocarcinoma, in which cells are poorly differentiated. If the mucus remains inside the tumor cell, it pushes the nucleus at the periphery, this occurs in "signet-ring cell." Depending on glandular architecture, cellular pleomorphism, and mucosecretion of the predominant pattern, adenocarcinoma may present three degrees of differentiation: well, moderately, and poorly differentiated.[5]

-

Cancer – Invasive adenocarcinoma (the most common type of colorectal cancer). The cancerous cells are seen in the center and at the bottom right of the image (blue). Near normal colon-lining cells are seen at the top right of the image.

-

Cancer – Histopathologic image of colonic carcinoid

-

Precancer – Tubular adenoma (left of image), a type of colonic polyp and a precursor of colorectal cancer. Normal colorectal mucosa is seen on the right.

-

Precancer – Colorectal villous adenoma

Microscopic criteria

[edit]

- A lesion at least "high grade intramucosal neoplasia" (high grade dysplasia) has:

- Severe cytologic atypia[6]

- Cribriform architecture, consisting of juxtaposed gland lumens without stroma in between, with loss of cell polarity. Rarely, they have foci of squamous differentiation (morules).[6]

- This should be distinguished from cases where piles of well-differentiated mucin-producing cells appear cribriform. In such piles, nuclei show regular polarity with apical mucin, and their nuclei are not markedly enlarged.[6]

- Invasive adenocarcinoma commonly displays:[6]

- Varying degrees of gland formation with tall columnar cells

- Frequently desmoplasia

- Dirty necrosis, consisting of extensive central necrosis with granular eosinophilic karyorrhectic cell detritus.[6][7] It is located within the glandular lumina,[7] or often with a garland of cribriform glands in their vicinity.[6]

-

Colorectal carcinoma with desmoplastic reaction (*)

-

Dirty necrosis

Subtyping

[edit]

Determining the specific histopathologic subtype of colorectal adenocardinoma is not as important as its staging (see #Staging section below), and about half cases do not have any specific subtype. Still, it is customary to specify it where applicable.

-

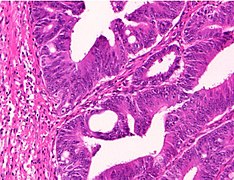

H&E stained sections:

(A) Serrated adenocarcinoma: epithelial serrations or tufts (thick blue arrow), abundant eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm, vesicular basal nuclei with preserved polarity.

(B) Mucinous carcinoma: Presence of extracellular mucin (>50%) associated with ribbons or tubular structures of neoplastic epithelium.

(C) Signet ring carcinoma: More than 50% of signet cells with infiltrative growth pattern (thin red arrow) or floating in large pools of mucin (thick red arrow).

(D) Medullary carcinoma: Neoplastic cells with syncytial appearance (thick yellow arrow) and eosinophilic cytoplasm associated with abundant peritumoral and intratumoral lymphocytes.[9] -

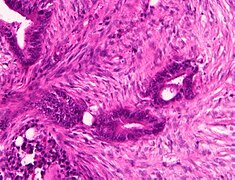

H&E stained sections:

(A)Lymphoepitelioma-like carcinoma: Poorly differentiated cells (red arrow) arranged in solid nests, tubules and trabeculae with poorly demarcated, infiltrative margins; intratumoral lymphoid infiltrate is extremely abundant.

(B) Cribiform comedo-type carcinoma: Cribriform gland (yellow arrow) with central necrosis comedo-like (yellow asterisk).

(C) Micropapillary carcinoma: Small, tight round to oval cohesive clusters of neoplastic cells (>5 cells) floating in clear spaces (double circle red-black), without endothelial lining and with no evidence of inflammatory cells.

(D) Low grade tubulo-glandular carcinoma: Very well-differentiated invasive glands with uniform circular or tubular profiles (blue arrow) with bland cytologic atypia.[9] -

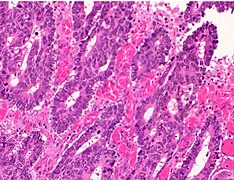

H&E stained sections:

(A) Villous carcinoma: invasive carcinoma with villous features consisting of usually intraglandular papillary projections (yellow arrow) associated with an expansile growth pattern, at the deep portions of the tumor.

(B) Squamous carcinoma: morphologically similar to other squamous cell carcinomas occurring in other organs with possible keratinization.

(C) Clear cell carcinoma: clear cell cytoplasm identified in polygonal cells with a central nucleus, columnar cells with an eccentric nucleus (red arrow) and/or round/oval cells with abundant cytoplasm and inconspicuous marginally located nucleus similar to lipocytes or lipoblasts.

(D) Hepatoid carcinoma: large polygonal-shaped cells, with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli and trabecular and pseudo-acinar growth pattern similar to hepatocarcinoma.[9] -

H&E stained sections

(A) Colorectal choriocarcinoma: biphasic solid nests and trabeculae of mononucleated cells with clear cytoplasm (thin yellow arrow) and pleomorphic cells with abundant vacuolated or eosinophilic cytoplasm and single or multiple vescicular nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli (thick yellow arrow).

(B) Rhabdoid colorectal carcinoma: rhabdoid cells characterized by a large, eccentrically located nuclei, prominent nucleoli (red arrow) and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm.

(C) Carcinoma with osseous metaplasia: osseous metaplasia (blue arrow) is recognized in conventional CRC as foci of bone formation in the stroma, with calcification, osteoid matrix, osteoclasts and osteoblasts.

(D) Undifferentiated carcinoma: sheets of undifferentiated cells showing a variable grade of pleomorphism with no gland formation, mucin production or other line of differentiation.[9]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Colorectal adenocarcinoma is distinguished from a colorectal adenoma (mainly tubular and ⁄or villous adenomas) mainly by invasion through the muscularis mucosae.[10]

In carcinoma in situ (Tis), cancer cells invade into the lamina propria, and may involve but not penetrating the muscularis mucosae. This can be classified as an adenoma with "high-grade dysplasia", because prognosis and management are essentially the same.[11]

Grading

[edit]Conventional adenocarcinoma may be graded as follows[12]

| >95% | 50-95% | <50% |

| Well differentiated | Moderately differentiated | Low differentiated |

| Low grade | High grade | |

-

Moderately differentiated colorectal carcinoma

-

Moderately-to-poorly differentiated colorectal carcinoma

-

Poorly differentiated colorectal carcinoma

Staging

[edit]

Staging is typically made according to the TNM staging system from the WHO organization, the UICC and the AJCC. The Astler-Coller classification (1954) and the Dukes classification (1932) are now less used. T stands for tumor stage and ranges from 0, no evidence of primary tumor, to T4 when the tumor penetrates the surface of the peritoneum or directly invades other organs or structures. The N stage reflects the number of metastatic lymph nodes and ranges from 0 (no lymph node metastasis) to 2 (four or more lymph node metastasis), and the M stage gives information about distant metastasis (M0 stands for no distant metastasis, and M1 for the presence of distant metastasis). A clinical classification (cTNM) is done at diagnosis and is based on MRI and CT, and a pathological TNM (pTNM) classification is performed after surgery.[13]

The most common metastasis sites for colorectal cancer are the liver, the lung and the peritoneum.[14]

Tumor budding

[edit]Tumor budding in colorectal cancer is loosely defined by the presence of individual cells and small clusters of tumor cells at the invasive front of carcinomas. It has been postulated to represent an epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). Tumor budding is a well-established independent marker of a potentially poor outcome in colorectal carcinoma that may allow for dividing people into risk categories more meaningful than those defined by TNM staging, and also potentially guide treatment decisions, especially in T1 and T3 N0 (Stage II, Dukes’ B) colorectal carcinoma. Unfortunately, its universal acceptance as a reportable factor has been held back by a lack of definitional uniformity with respect to both qualitative and quantitative aspects of tumor budding.[15]

Immunohistochemistry

[edit]In cases where a metastasis from colorectal cancer is suspected, immunohistochemistry is used to ascertain correct diagnosis.[16] Some proteins are more specifically expressed in colorectal cancer and can be used as diagnostic markers such as CK20 and MUC2.[16] Immunohistochemistry can also be used to screen for Lynch syndrome, a genetic disorder with increased risk of colorectal and other cancers. The diagnosis of Lynch syndrome is made by looking for specific genetic mutations in genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2.[17] Immunohistochemical testing can also be used to guide treatment and assist in determining the prognosis. Certain markers isolated from the tumor can indicate specific cancer types or susceptibility to different treatments.[18]

References

[edit]- ^ Kang, Hakjung; O’Connell, Jessica B.; Leonardi, Michael J.; Maggard, Melinda A.; McGory, Marcia L.; Ko, Clifford Y. (2006). "Rare tumors of the colon and rectum: a national review". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 22 (2): 183–189. doi:10.1007/s00384-006-0145-2. ISSN 0179-1958. PMID 16845516. S2CID 34693873.

- ^ "Colon, Rectosigmoid, and Rectum Equivalent Terms and Definitions C180-C189, C199, C209, (Excludes lymphoma and leukemia M9590 – M9992 and Kaposi sarcoma M9140) - Colon Solid Tumor Rules 2018. July 2019 Update" (PDF). National Cancer Institute.

- ^ "Colorectal cancer types". Cancer Treatment Centers of America. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ Di Como, Joseph A. (October 2015). "Adenosquamous carcinoma of the colon and rectum: a population based clinical outcomes study involving 578 patients from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result (SEER) database (1973–2010)". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 221 (4): 56. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.08.044.

- ^ "Moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (colon)". pathologyatlas.ro. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Robert V Rouse. "Adenocarcinoma of the Colon and Rectum". Stanford University School of Medicine. Original posting/updates: 1/31/10, 7/15/11, 11/12/11

- ^ a b Li, Lianhuang; Jiang, Weizhong; Yang, Yinghong; Chen, Zhifen; Feng, Changyin; Li, Hongsheng; Guan, Guoxian; Chen, Jianxin (2014). "Identification of dirty necrosis in colorectal carcinoma based on multiphoton microscopy". Journal of Biomedical Optics. 19 (6): 066008. Bibcode:2014JBO....19f6008L. doi:10.1117/1.JBO.19.6.066008. ISSN 1083-3668. PMID 24967914. S2CID 8053157.

- ^ Remo, Andrea; Fassan, Matteo; Vanoli, Alessandro; Bonetti, Luca Reggiani; Barresi, Valeria; Tatangelo, Fabiana; Gafà, Roberta; Giordano, Guido; Pancione, Massimo; Grillo, Federica; Mastracci, Luca (2019). "Morphology and Molecular Features of Rare Colorectal Carcinoma Histotypes". Cancers. 11 (7): 1036. doi:10.3390/cancers11071036. ISSN 2072-6694. PMC 6678907. PMID 31340478.

- ^ a b c d Initially copied from: Remo, Andrea; Fassan, Matteo; Vanoli, Alessandro; Bonetti, Luca Reggiani; Barresi, Valeria; Tatangelo, Fabiana; Gafà, Roberta; Giordano, Guido; Pancione, Massimo; Grillo, Federica; Mastracci, Luca (2019). "Morphology and Molecular Features of Rare Colorectal Carcinoma Histotypes". Cancers. 11 (7): 1036. doi:10.3390/cancers11071036. ISSN 2072-6694. PMC 6678907. PMID 31340478. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license

- ^ Robert V Rouse. "Colorectal Adenoma Containing Invasive Adenocarcinoma". Stanford University School of Medicine.

- ^ Finlay A Macrae. "Overview of colon polyps". UpToDate. This topic last updated: Dec 10, 2018.

- ^ :Fleming M, Ravula S, Tatishchev SF, Wang HL (September 2012). "Colorectal carcinoma: Pathologic aspects". J Gastrointest Oncol. 3 (3): 153–73. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2012.030. PMC 3418538. PMID 22943008.

- ^ "Colon and Rectum Cancer Staging, American Joint Committee on Cancer, 7th Edition" (PDF). Retrieved 27 Feb 2019.

- ^ "Metastatic Cancer". National Cancer Institute. February 6, 2017. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ Mitrovic B, Schaeffer DF, Riddell RH, Kirsch R (October 2012). "Tumor budding in colorectal carcinoma: time to take notice". Modern Pathology. 25 (10): 1315–1325. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.94. PMID 22790014.

- ^ a b Taliano RJ, LeGolvan M, Resnick MB (February 2013). "Immunohistochemistry of colorectal carcinoma: current practice and evolving applications". Human Pathology. 44 (2): 151–163. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2012.04.017. PMID 22939578.

- ^ Bui QM, Lin D, Ho W (February 2017). "Approach to Lynch Syndrome for the Gastroenterologist". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 62 (2): 299–304. doi:10.1007/s10620-016-4346-4. PMID 27990589. S2CID 32833106.

- ^ Vakiani E (December 2017). "Molecular Testing of Colorectal Cancer in the Modern Era: What Are We Doing and Why?". Surgical Pathology Clinics. 10 (4): 1009–1020. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.07.013. PMID 29103530.

![H&E stained sections: (A) Serrated adenocarcinoma: epithelial serrations or tufts (thick blue arrow), abundant eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm, vesicular basal nuclei with preserved polarity. (B) Mucinous carcinoma: Presence of extracellular mucin (>50%) associated with ribbons or tubular structures of neoplastic epithelium. (C) Signet ring carcinoma: More than 50% of signet cells with infiltrative growth pattern (thin red arrow) or floating in large pools of mucin (thick red arrow). (D) Medullary carcinoma: Neoplastic cells with syncytial appearance (thick yellow arrow) and eosinophilic cytoplasm associated with abundant peritumoral and intratumoral lymphocytes.[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Micrograph_of_serrated_adenocarcinoma%2C_mucinous_carcinoma%2C_signet_ring_carcinoma_and_medullary_carcinoma.jpg/696px-Micrograph_of_serrated_adenocarcinoma%2C_mucinous_carcinoma%2C_signet_ring_carcinoma_and_medullary_carcinoma.jpg)

![H&E stained sections: (A)Lymphoepitelioma-like carcinoma: Poorly differentiated cells (red arrow) arranged in solid nests, tubules and trabeculae with poorly demarcated, infiltrative margins; intratumoral lymphoid infiltrate is extremely abundant. (B) Cribiform comedo-type carcinoma: Cribriform gland (yellow arrow) with central necrosis comedo-like (yellow asterisk). (C) Micropapillary carcinoma: Small, tight round to oval cohesive clusters of neoplastic cells (>5 cells) floating in clear spaces (double circle red-black), without endothelial lining and with no evidence of inflammatory cells. (D) Low grade tubulo-glandular carcinoma: Very well-differentiated invasive glands with uniform circular or tubular profiles (blue arrow) with bland cytologic atypia.[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Micrograph_of_lymphoepitelioma-like_carcinoma%2C_cribiform_comedo-type_carcinoma%2C_micropapillary_carcinoma_and_low_grade_tubulo-glandular_carcinoma.jpg/700px-Micrograph_of_lymphoepitelioma-like_carcinoma%2C_cribiform_comedo-type_carcinoma%2C_micropapillary_carcinoma_and_low_grade_tubulo-glandular_carcinoma.jpg)

![H&E stained sections: (A) Villous carcinoma: invasive carcinoma with villous features consisting of usually intraglandular papillary projections (yellow arrow) associated with an expansile growth pattern, at the deep portions of the tumor. (B) Squamous carcinoma: morphologically similar to other squamous cell carcinomas occurring in other organs with possible keratinization. (C) Clear cell carcinoma: clear cell cytoplasm identified in polygonal cells with a central nucleus, columnar cells with an eccentric nucleus (red arrow) and/or round/oval cells with abundant cytoplasm and inconspicuous marginally located nucleus similar to lipocytes or lipoblasts. (D) Hepatoid carcinoma: large polygonal-shaped cells, with granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli and trabecular and pseudo-acinar growth pattern similar to hepatocarcinoma.[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8d/Micrograph_of_villous_carcinoma%2C_squamous_carcinoma%2C_clear_cell_carcinoma_and_hepatoid_carcinoma.jpg/695px-Micrograph_of_villous_carcinoma%2C_squamous_carcinoma%2C_clear_cell_carcinoma_and_hepatoid_carcinoma.jpg)

![H&E stained sections (A) Colorectal choriocarcinoma: biphasic solid nests and trabeculae of mononucleated cells with clear cytoplasm (thin yellow arrow) and pleomorphic cells with abundant vacuolated or eosinophilic cytoplasm and single or multiple vescicular nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli (thick yellow arrow). (B) Rhabdoid colorectal carcinoma: rhabdoid cells characterized by a large, eccentrically located nuclei, prominent nucleoli (red arrow) and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. (C) Carcinoma with osseous metaplasia: osseous metaplasia (blue arrow) is recognized in conventional CRC as foci of bone formation in the stroma, with calcification, osteoid matrix, osteoclasts and osteoblasts. (D) Undifferentiated carcinoma: sheets of undifferentiated cells showing a variable grade of pleomorphism with no gland formation, mucin production or other line of differentiation.[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ea/Micrograph_of_colorectal_choriocarcinoma%2C_rhabdoid_colorectal_carcinoma%2C_carcinoma_with_osseous_metaplasia_and_undifferentiated_carcinoma.jpg/695px-Micrograph_of_colorectal_choriocarcinoma%2C_rhabdoid_colorectal_carcinoma%2C_carcinoma_with_osseous_metaplasia_and_undifferentiated_carcinoma.jpg)