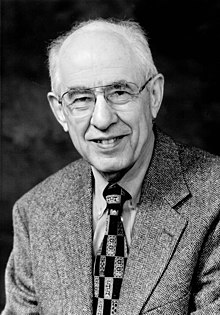

Hilary Putnam

Hilary Whitehall Putnam (/ˈpʌtnəm/; July 31, 1926 – March 13, 2016) was an American philosopher, mathematician, computer scientist, and figure in analytic philosophy in the second half of the 20th century. He contributed to the studies of philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, philosophy of mathematics, and philosophy of science.[5] Outside philosophy, Putnam contributed to mathematics and computer science. Together with Martin Davis he developed the Davis–Putnam algorithm for the Boolean satisfiability problem[6] and he helped demonstrate the unsolvability of Hilbert's tenth problem.[7]

Putnam applied equal scrutiny to his own philosophical positions as to those of others, subjecting each position to rigorous analysis until he exposed its flaws.[8] As a result, he acquired a reputation for frequently changing his positions.[9] In philosophy of mind, Putnam argued against the type-identity of mental and physical states based on his hypothesis of the multiple realizability of the mental, and for the concept of functionalism, an influential theory regarding the mind–body problem.[5][10] Putnam also originated the computational theory of mind.[11] In philosophy of language, along with Saul Kripke and others, he developed the causal theory of reference, and formulated an original theory of meaning, introducing the notion of semantic externalism based on a thought experiment called Twin Earth.[12]

In philosophy of mathematics, Putnam and W. V. O. Quine developed the Quine–Putnam indispensability argument, an argument for the reality of mathematical entities,[13] later espousing the view that mathematics is not purely logical, but "quasi-empirical".[14] In epistemology, Putnam criticized the "brain in a vat" thought experiment, which appears to provide a powerful argument for epistemological skepticism, by challenging its coherence.[15] In metaphysics, he originally espoused a position called metaphysical realism, but eventually became one of its most outspoken critics, first adopting a view he called "internal realism",[16] which he later abandoned. Despite these changes of view, throughout his career Putnam remained committed to scientific realism, roughly the view that mature scientific theories are approximately true descriptions of ways things are.[17]

In his later work, Putnam became increasingly interested in American pragmatism, Jewish philosophy, and ethics, engaging with a wider array of philosophical traditions. He also displayed an interest in metaphilosophy, seeking to "renew philosophy" from what he identified as narrow and inflated concerns.[18] He was at times a politically controversial figure, especially for his involvement with the Progressive Labor Party in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[19]

Life

[edit]Hilary Whitehall Putnam was born on July 31, 1926, in Chicago, Illinois.[20] His father, Samuel Putnam, was a scholar of Romance languages, columnist, and translator who wrote for the Daily Worker, a publication of the American Communist Party, from 1936 to 1946.[21] Because of his father's commitment to communism, Putnam had a secular upbringing, although his mother, Riva, was Jewish.[8] In early 1927, six months after Hilary's birth, the family moved to France, where Samuel was under contract to translate the surviving works of François Rabelais.[18][20] In a 2015 autobiographical essay, Putnam said that his first childhood memories were from his life in France, and his first language was French.[18]

Putnam completed the first two years of his primary education in France before he and his parents returned to the U.S. in 1933, settling in Philadelphia.[20] There, he attended Central High School, where he met Noam Chomsky, who was a year behind him.[18]: 8 The two remained friends—and often intellectual opponents—for the rest of Putnam's life.[22] Putnam studied philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, receiving his B.A. degree and becoming a member of the Philomathean Society, the country's oldest continually existing collegiate literary society.[8][23] He did graduate work in philosophy at Harvard University[8] and later at UCLA's philosophy department, where he received his Ph.D. in 1951 for his dissertation, The Meaning of the Concept of Probability in Application to Finite Sequences.[2][24] Putnam's dissertation supervisor Hans Reichenbach was a leading figure in logical positivism, the dominant school of philosophy of the day; one of Putnam's most consistent positions was his rejection of logical positivism as self-defeating.[23] Over the course of his life, Putnam was his own philosophical adversary, changing his positions on philosophical questions and critiquing his previous views.[12]

After obtaining his PhD, Putnam taught at Northwestern University (1951–52), Princeton University (1953–61), and MIT (1961–65). For the rest of his career, Putnam taught at Harvard's philosophy department, becoming Cogan University Professor. In 1962, he married fellow philosopher Ruth Anna Putnam (born Ruth Anna Jacobs), who took a teaching position in philosophy at Wellesley College.[23][25][26] Rebelling against the antisemitism they experienced during their youth, the Putnams decided to establish a traditional Jewish home for their children.[27] Since they had no experience with the rituals of Judaism, they sought out invitations to other Jewish homes for Seder. They began to study Jewish rituals and Hebrew, became more interested in Judaism, self-identified as Jews, and actively practiced Judaism. In 1994, Hilary celebrated a belated bar mitzvah service; Ruth Anna's bat mitzvah was celebrated four years later.[27]

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Putnam was an active supporter of the American Civil Rights Movement and he was also an active opponent of the Vietnam War.[19] In 1963, he organized one of MIT's first faculty and student anti-war committees.[23][25] After moving to Harvard in 1965, he organized campus protests and began teaching courses on Marxism. Putnam became an official faculty advisor to the Students for a Democratic Society and in 1968 a member of the Progressive Labor Party (PLP).[23][25] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1965.[28] After 1968, his political activities centered on the PLP.[19] The Harvard administration considered these activities disruptive and attempted to censure Putnam.[29][30] Putnam permanently severed his relationship with the PLP in 1972.[31] In 1997, at a meeting of former draft resistance activists at Boston's Arlington Street Church, he called his involvement with the PLP a mistake. He said he had been impressed at first with the PLP's commitment to alliance-building and its willingness to attempt to organize from within the armed forces.[19]

In 1976, Putnam was elected president of the American Philosophical Association. The next year, he was selected as Walter Beverly Pearson Professor of Mathematical Logic in recognition of his contributions to the philosophy of logic and mathematics. While breaking with his radical past, Putnam never abandoned his belief that academics have a particular social and ethical responsibility toward society. He continued to be forthright and progressive in his political views, as expressed in the articles "How Not to Solve Ethical Problems" (1983) and "Education for Democracy" (1993).[23]

Putnam was a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy. He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1999.[32] He retired from teaching in June 2000, becoming Cogan University Professor Emeritus, but as of 2009 continued to give a seminar almost yearly at Tel Aviv University. He also held the Spinoza Chair of Philosophy at the University of Amsterdam in 2001.[33] His corpus includes five volumes of collected works, seven books, and more than 200 articles. Putnam's renewed interest in Judaism inspired him to publish several books and essays on the topic.[34] With his wife, he co-authored several essays and a book on the late-19th-century American pragmatist movement.[23]

For his contributions in philosophy and logic, Putnam was awarded the Rolf Schock Prize in 2011[35] and the Nicholas Rescher Prize for Systematic Philosophy in 2015.[36] Putnam died at his home in Arlington, Massachusetts, on March 13, 2016.[37] At the time of his death, Putnam was Cogan University Professor Emeritus at Harvard University.

Philosophy of mind

[edit]Multiple realizability

[edit]

Putnam's best-known work concerns philosophy of mind. His most noted original contributions to that field came in several key papers published in the late 1960s that set out the hypothesis of multiple realizability.[38] In these papers, Putnam argues that, contrary to the famous claim of the type-identity theory, pain may correspond to utterly different physical states of the nervous system in different organisms even if they all experience the same mental state of "being in pain".[38] Putnam cited examples from the animal kingdom to illustrate his thesis. He asked whether it was likely that the brain structures of diverse types of animals realize pain, or other mental states, the same way. If they do not share the same brain structures, they cannot share the same mental states and properties, in which case mental states must be realized by different physical states in different species. Putnam then took his argument a step further, asking about such things as the nervous systems of alien beings, artificially intelligent robots and other silicon-based life forms. These hypothetical entities, he contended, should not be considered incapable of experiencing pain just because they lack human neurochemistry. Putnam concluded that type-identity theorists had been making an "ambitious" and "highly implausible" conjecture that could be disproved by one example of multiple realizability. This is sometimes called the "likelihood argument", as it focuses on the claim that multiple realizability is more likely than type-identity theory.[39][40]: 640

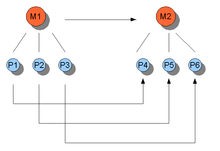

Putnam also formulated an a priori argument in favor of multiple realizability based on what he called "functional isomorphism". He defined the concept in these terms: "Two systems are functionally isomorphic if 'there is a correspondence between the states of one and the states of the other that preserves functional relations'." In the case of computers, two machines are functionally isomorphic if and only if the sequential relations among states in the first exactly mirror the sequential relations among states in the other. Therefore, a computer made of silicon chips and one made of cogs and wheels can be functionally isomorphic but constitutionally diverse. Functional isomorphism implies multiple realizability.[39][40]: 637

Putnam, Jerry Fodor, and others argued that along with being an effective argument against type-identity theories, multiple realizability implies that any low-level explanation of higher-level mental phenomena is insufficiently abstract and general. Functionalism, which identifies mental kinds with functional kinds that are characterized exclusively in terms of causes and effects, abstracts from the level of microphysics, and therefore seemed to be a better explanation of the relation between mind and body. In fact, there are many functional kinds, including mousetraps and eyes, that are multiply realized at the physical level.[39][41][40]: 648–649 [42]: 6

Multiple realizability has been criticized on the grounds that, if it were true, research and experimentation in the neurosciences would be impossible.[43] According to William Bechtel and Jennifer Mundale, to be able to conduct such research in the neurosciences, universal consistencies must either exist or be assumed to exist in brain structures. It is the similarity (or homology) of brain structures that allows us to generalize across species.[43] If multiple realizability were an empirical fact, results from experiments conducted on one species of animal (or one organism) would not be meaningful when generalized to explain the behavior of another species (or organism of the same species).[44] Jaegwon Kim, David Lewis, Robert Richardson and Patricia Churchland have also criticized metaphysical realism.[45][46][47][48]

Machine state functionalism

[edit]Putnam himself put forth the first formulation of such a functionalist theory. This formulation, now called "machine-state functionalism", was inspired by analogies Putnam and others made between the mind and Turing machines.[49] The point for functionalism is the nature of the states of the Turing machine. Each state can be defined in terms of its relations to the other states and to the inputs and outputs, and the details of how it accomplishes what it accomplishes and of its material constitution are completely irrelevant. According to machine-state functionalism, the nature of a mental state is just like the nature of a Turing machine state. Just as "state one" simply is the state in which, given a particular input, such-and-such happens, so being in pain is the state which disposes one to cry "ouch", become distracted, wonder what the cause is, and so forth.[50]

Rejection of functionalism

[edit]Ian Hacking called Representation and Reality (1988) a book that "will mostly be read as Putnam’s denunciation of his former philosophical psychology, to which he gave the name 'functionalism'."[51] Writing in Noûs, Barbara Hannon described "the inventor of functionalism" as arguing "against his own former computationalist views".[52]

Putnam's change of mind was primarily due to the difficulties computational theories have in explaining certain intuitions with respect to the externalism of mental content.[53] This is illustrated by his Twin Earth thought experiment.[non-primary source needed]

In 1988 Putnam also developed a separate argument against functionalism based on Fodor's generalized version of multiple realizability. Asserting that functionalism is really a watered-down identity theory in which mental kinds are identified with functional kinds, he argued that mental kinds may be multiply realizable over functional kinds. The argument for functionalism is that the same mental state could be implemented by the different states of a universal Turing machine.[54][non-primary source needed]

Despite Putnam's rejection of functionalism, it has continued to flourish and been developed into numerous versions by Fodor, David Marr, Daniel Dennett, and David Lewis, among others.[55] Functionalism helped lay the foundations for modern cognitive science[55] and is the dominant theory of mind in philosophy today.[56]

By 2012 Putnam accepted a modification of functionalism called "liberal functionalism". The view holds that "what matters for consciousness and for mental properties generally is the right sort of functional capacities and not the particular matter that subserves those capacities".[57] The specification of these capacities may refer to what goes on outside the organism's "brain", may include intentional idioms, and need not describe a capacity to compute something or other.[57]

Putnam himself formulated one of the main arguments against functionalism, the Twin Earth thought experiment, though there have been additional criticisms. John Searle's Chinese room argument (1980) is a direct attack on the claim that thought can be represented as a set of functions. It is designed to show that it is possible to mimic intelligent action with a purely functional system, without any interpretation or understanding. Searle describes a situation in which a person who speaks only English is locked in a room with Chinese symbols in baskets and a rule book in English for moving the symbols around. People outside the room instruct the person inside to follow the rule book for sending certain symbols out of the room when given certain symbols. The people outside the room speak Chinese and are communicating with the person inside via the Chinese symbols. According to Searle, it would be absurd to claim that the English speaker inside "knows" Chinese based on these syntactic processes alone. This argument attempts to show that systems that operate merely on syntactic processes cannot realize any semantics (meaning) or intentionality (aboutness). Searle thus attacks the idea that thought can be equated with following a set of syntactic rules and concludes that functionalism is an inadequate theory of the mind.[58] Ned Block has advanced several other arguments against functionalism.[59]

Philosophy of language

[edit]Semantic externalism

[edit]One of Putnam's contributions to philosophy of language is his semantic externalism, the claim that terms' meanings are determined by factors outside the mind, encapsulated in his slogan that "meaning just ain't in the head". His views on meaning, first laid out in Meaning and Reference (1973), then in The Meaning of "Meaning" (1975), use his "Twin Earth" thought experiment to defend this thesis.[60][61]

Twin Earth shows this, according to Putnam, since on Twin Earth everything is identical to Earth, except that its lakes, rivers and oceans are filled with XYZ rather than H2O. Consequently, when an earthling, Fredrick, uses the Earth-English word "water", it has a different meaning from the Twin Earth-English word "water" when used by his physically identical twin, Frodrick, on Twin Earth. Since Fredrick and Frodrick are physically indistinguishable when they utter their respective words, and since their words have different meanings, meaning cannot be determined solely by what is in their heads.[62] This led Putnam to adopt a version of semantic externalism with regard to meaning and mental content.[15][39] The philosopher of mind and language Donald Davidson, despite his many differences of opinion with Putnam, wrote that semantic externalism constituted an "anti-subjectivist revolution" in philosophers' way of seeing the world. Since Descartes's time, philosophers had been concerned with proving knowledge from the basis of subjective experience. Thanks to Putnam, Saul Kripke, Tyler Burge and others, Davidson said, philosophy could now take the objective realm for granted and start questioning the alleged "truths" of subjective experience.[63]

Theory of meaning

[edit]Along with Kripke, Keith Donnellan, and others, Putnam contributed to what is known as the causal theory of reference.[5] In particular, he maintained in The Meaning of "Meaning" that the objects referred to by natural kind terms—such as "tiger", "water", and "tree"—are the principal elements of the meaning of such terms. There is a linguistic division of labor, analogous to Adam Smith's economic division of labor, according to which such terms have their references fixed by the "experts" in the particular field of science to which the terms belong. So, for example, the reference of the term "lion" is fixed by the community of zoologists, the reference of the term "elm tree" is fixed by the community of botanists, and chemists fix the reference of the term "table salt" as sodium chloride. These referents are considered rigid designators in the Kripkean sense and are disseminated outward to the linguistic community.[39][64]: 33

Putnam specifies a finite sequence of elements (a vector) for the description of the meaning of every term in the language. Such a vector consists of four components:

- the object to which the term refers, e.g., the object individuated by the chemical formula H2O;

- a set of typical descriptions of the term, referred to as "the stereotype", e.g., "transparent", "colorless", and "hydrating";

- the semantic indicators that place the object into a general category, e.g., "natural kind" and "liquid";

- the syntactic indicators, e.g., "concrete noun" and "mass noun".

Such a "meaning-vector" provides a description of the reference and use of an expression within a particular linguistic community. It provides the conditions for its correct usage and makes it possible to judge whether a single speaker attributes the appropriate meaning to it or whether its use has changed enough to cause a difference in its meaning. According to Putnam, it is legitimate to speak of a change in the meaning of an expression only if the reference of the term, and not its stereotype, has changed.[18]: 339–340 But since no possible algorithm can determine which aspect—the stereotype or the reference—has changed in a particular case, it is necessary to consider the usage of other expressions of the language.[39][non-primary source needed] Since there is no limit to the number of such expressions to be considered, Putnam embraced a form of semantic holism.[65]

Despite the many changes in his other positions, Putnam consistently adhered to semantic holism. Michael Dummett, Jerry Fodor, Ernest Lepore, and others have identified problems with this position. In the first place, they suggest that, if semantic holism is true, it is impossible to understand how a speaker of a language can learn the meaning of an expression in the language. Given the limits of our cognitive abilities, we will never be able to master the whole of the English (or any other) language, even based on the (false) assumption that languages are static and immutable entities. Thus, if one must understand all of a natural language to understand a single word or expression, language learning is simply impossible. Semantic holism also fails to explain how two speakers can mean the same thing when using the same expression, and therefore how any communication is possible between them. Given a sentence P, since Fred and Mary have each mastered different parts of the English language and P is related in different ways to the sentences in each part, P means one thing to Fred and something else to Mary. Moreover, if P derives its meaning from its relations with all the sentences of a language, as soon as the vocabulary of an individual changes by the addition or elimination of a sentence, the totality of relations changes, and therefore also the meaning of P. As this is a common phenomenon, the result is that P has two different meanings in two different moments in the life of the same person. Consequently, if one accepts the truth of a sentence and then rejects it later on, the meaning of what one rejected and what one accepted are completely different and therefore one cannot change opinions with regard to the same sentences.[66][page needed][67][page needed][68][page needed]

Philosophy of mathematics

[edit]In the philosophy of mathematics, Putnam has utilized indispensability arguments to argue for a realist interpretation of mathematics. In his 1971 book Philosophy of Logic, he presented what has since been called the locus classicus of the Quine–Putnam indispensability argument.[13] The argument, which he attributed to Willard Van Orman Quine, is presented in the book as "quantification over mathematical entities is indispensable for science, both formal and physical; therefore we should accept such quantification; but this commits us to accepting the existence of the mathematical entities in question."[69] According to Charles Parsons, Putnam "very likely" endorsed this version of the argument in his early work, but later came to deny some of the views present in it.[70]: 128

In 1975, Putnam formulated his own indispensability argument based on the no miracles argument in the philosophy of science, saying, "I believe that the positive argument for realism [in science] has an analogue in the case of mathematical realism. Here too, I believe, realism is the only philosophy that doesn't make the success of the science a miracle".[71] According to Putnam, Quine's version of the argument was an argument for the existence of abstract mathematical objects, while Putnam's own argument was simply for a realist interpretation of mathematics, which he believed could be provided by a "mathematics as modal logic" interpretation that need not imply the existence of abstract objects.[70]: 61–62

Putnam also held the view that mathematics, like physics and other empirical sciences, uses both strict logical proofs and "quasi-empirical" methods.[72]: 150 For example, Fermat's Last Theorem states that for no integer are there positive integer values of x, y, and z such that . Before Andrew Wiles proved this for all in 1995,[73] it had been proved for many values of n. These proofs inspired further research in the area, and formed a quasi-empirical consensus for the theorem. Even though such knowledge is more conjectural than a strictly proved theorem, it was still used in developing other mathematical ideas.[14]

The Quine–Putnam indispensability argument has been extremely influential in the philosophy of mathematics, inspiring continued debate and development of the argument in contemporary philosophy of mathematics. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, many in the field consider it the best argument for mathematical realism.[13] Prominent counterarguments come from Hartry Field, who argues that mathematics is not indispensable to science, and Penelope Maddy and Elliott Sober, who dispute whether we are committed to mathematical realism even if it is indispensable to science.[13]

Mathematics and computer science

[edit]Putnam has contributed to scientific fields not directly related to his work in philosophy.[5] As a mathematician, he contributed to the resolution of Hilbert's tenth problem in mathematics. This problem (now known as Matiyasevich's theorem or the MRDP theorem) was settled by Yuri Matiyasevich in 1970, with a proof that relied heavily on previous research by Putnam, Julia Robinson and Martin Davis.[74]

In computability theory, Putnam investigated the structure of the ramified analytical hierarchy, its connection with the constructible hierarchy and its Turing degrees. He showed that there are many levels of the constructible hierarchy that add no subsets of the integers.[75] Later, with his student George Boolos, he showed that the first such "non-index" is the ordinal of ramified analysis[76] (this is the smallest such that is a model of full second-order comprehension). Also, together with a separate paper with his student Richard Boyd and Gustav Hensel, he demonstrated how the Davis–Mostowski–Kleene hyperarithmetical hierarchy of arithmetical degrees can be naturally extended up to .[77]

In computer science, Putnam is known for the Davis–Putnam algorithm for the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT), developed with Martin Davis in 1960.[5] The algorithm finds whether there is a set of true or false values that satisfies a given Boolean expression so that the entire expression becomes true. In 1962, they further refined the algorithm with the help of George Logemann and Donald W. Loveland. It became known as the DPLL algorithm. It is efficient and still forms the basis of most complete SAT solvers.[6]

Epistemology

[edit]

In epistemology, Putnam is known for his argument against skeptical scenarios based on the "brain in a vat" thought experiment (a modernized version of Descartes's evil demon hypothesis). The argument is that one cannot coherently suspect that one is a disembodied "brain in a vat" placed there by some "mad scientist".[15][78]

This follows from the causal theory of reference. Words always refer to the kinds of things they were coined to refer to, the kinds of things their user, or the user's ancestors, experienced. So, if some person, Mary, is a "brain in a vat", whose every experience is received through wiring and other gadgetry created by the mad scientist, then Mary's idea of a brain does not refer to a real brain, since she and her linguistic community have never encountered such a thing. To her a brain is actually an image fed to her through the wiring. Nor does her idea of a vat refer to a real vat. So if, as a brain in a vat, she says, "I'm a brain in a vat", she is actually saying, "I'm a brain-image in a vat-image", which is incoherent. On the other hand, if she is not a brain in a vat, then saying that she is a brain in a vat is still incoherent, because she actually means the opposite. This is a form of epistemological externalism: knowledge or justification depends on factors outside the mind and is not solely determined internally.[15][78]

Putnam has clarified that his real target in this argument was never skepticism, but metaphysical realism, which he thought implied such skeptical scenarios were possible.[79][80] Since realism of this kind assumes the existence of a gap between how one conceives the world and the way the world really is, skeptical scenarios such as this one (or Descartes's evil demon) present a formidable challenge. By arguing that such a scenario is impossible, Putnam attempts to show that this notion of a gap between one's concept of the world and the way it is is absurd. One cannot have a "God's-eye" view of reality. One is limited to one's conceptual schemes, and metaphysical realism is therefore false.[81][82]

Putnam's brain in a vat argument has been criticized.[83] Crispin Wright argues that Putnam's formulation of the brain-in-a-vat scenario is too narrow to refute global skepticism. The possibility that one is a recently disembodied brain in a vat is not undermined by semantic externalism. If a person has lived her entire life outside the vat—speaking the English language and interacting normally with the outside world—prior to her "envatment" by a mad scientist, when she wakes up inside the vat, her words and thoughts (e.g., "tree" and "grass") will still refer to the objects or events in the external world that they referred to before her envatment.[80]

Metaphilosophy and ontology

[edit]In the late 1970s and the 1980s, stimulated by results from mathematical logic and by some of Quine's ideas, Putnam abandoned his long-standing defense of metaphysical realism—the view that the categories and structures of the external world are both causally and ontologically independent of the conceptualizations of the human mind—and adopted a rather different view, which he called "internal realism" or "pragmatic realism".[84]: 404 [85][86] Internal realism is the view that, although the world may be causally independent of the human mind, the world's structure—its division into kinds, individuals and categories—is a function of the human mind, and hence the world is not ontologically independent. The general idea is influenced by Immanuel Kant's idea of the dependence of our knowledge of the world on the categories of thought.[87]

According to Putnam, the problem with metaphysical realism is that it fails to explain the possibility of reference and truth.[88] According to the metaphysical realist, our concepts and categories refer because they match up in some mysterious manner with the categories, kinds and individuals inherent in the external world. But how is it possible that the world "carves up" into certain structures and categories, the mind carves up the world into its own categories and structures, and the two carvings perfectly coincide? The answer must be that the world does not come pre-structured but that the human mind and its conceptual schemes impose structure on it.[82] In Reason, Truth, and History, Putnam identified truth with what he termed "idealized rational acceptability." The theory is that a belief is true if it would be accepted by anyone under ideal epistemic conditions.[16][84]: §7.1

Nelson Goodman formulated a similar notion in Fact, Fiction and Forecast (1956). "We have come to think of the actual as one among many possible worlds. We need to repaint that picture. All possible worlds lie within the actual one", Goodman wrote.[89] Putnam rejected this form of social constructivism, but retained the idea that there can be many correct descriptions of reality. None of these descriptions can be scientifically proven to be the "one, true" description of the world. He thus accepted "conceptual relativity"—the view that it may be a matter of choice or convention, e.g., whether mereological sums exist, or whether spacetime points are individuals or mere limits.[90][non-primary source needed]

Curtis Brown has criticized Putnam's internal realism as a disguised form of subjective idealism, in which case it is subject to the traditional arguments against that position. In particular, it falls into the trap of solipsism. That is, if existence depends on experience, as subjective idealism maintains, and if one's consciousness ceased to exist, then the rest of the universe would also cease to exist.[87] In his reply to Simon Blackburn in the volume Reading Putnam, Putnam renounced internal realism[12] because it assumed a "cognitive interface" model of the relation between the mind and the world. Under the increasing influence of William James and the pragmatists, he adopted a direct realist view of this relation.[91][92][93]: 23–24 Although he abandoned internal realism, Putnam still resisted the idea that any given thing or system of things can be described in exactly one complete and correct way. He came to accept metaphysical realism in a broader sense, rejecting all forms of verificationism and all talk of our "making" the world.[94]

In the philosophy of perception, Putnam came to endorse direct realism, according to which perceptual experiences directly present one with the external world. He once further held that there are no mental representations, sense data, or other intermediaries between the mind and the world.[53] By 2012, however, he rejected this commitment in favor of "transactionalism", a view that accepts both that perceptual experiences are world-involving transactions, and that these transactions are functionally describable (provided that worldly items and intentional states may be referred to in the specification of the function). Such transactions can further involve qualia.[57][95]

Quantum mechanics

[edit]During his career, Putnam espoused various positions on the interpretation of quantum mechanics.[96] In the 1960s and 1970s, he contributed to the quantum logic tradition, holding that the way to resolve quantum theory's apparent paradoxes is to modify the logical rules by which propositions' truth values are deduced.[97][98] Putnam's first foray into this topic was "A Philosopher Looks at Quantum Mechanics" in 1965, followed by his 1969 essay "Is Logic Empirical?". He advanced different versions of quantum logic over the years,[99] and eventually turned away from it in the 1990s, due to critiques by Nancy Cartwright, Michael Redhead, and others.[12]: 265–280 In 2005, he wrote that he rejected the many-worlds interpretation because he could see no way for it to yield meaningful probabilities.[100] He found both de Broglie–Bohm theory and the spontaneous collapse theory of Ghirardi, Rimini, and Weber to be promising, yet also dissatisfying, since it was not clear that either could be made fully consistent with special relativity's symmetry requirements.[96]

Neopragmatism and Wittgenstein

[edit]In the mid-1970s, Putnam became increasingly disillusioned with what he perceived as modern analytic philosophy's "scientism" and focus on metaphysics over ethics and everyday concerns.[101]: 186–190 He also became convinced by his readings of James and John Dewey that there is no fact–value dichotomy; that is, normative (e.g., ethical and aesthetic) judgments often have a factual basis, while scientific judgments have a normative element.[90][12]: 240 For a time, under Ludwig Wittgenstein's influence, Putnam adopted a pluralist view of philosophy itself and came to view most philosophical problems as no more than conceptual or linguistic confusions philosophers created by using ordinary language out of context.[90][non-primary source needed] A book of articles on pragmatism by Ruth Anna Putnam and Hilary Putnam, Pragmatism as a Way of Life: The Lasting Legacy of William James and John Dewey, edited by David Macarthur, was published in 2017.[102]

Many of Putnam's last works addressed the concerns of ordinary people, particularly social problems.[103] For example, he wrote about the nature of democracy, social justice and religion. He also discussed Jürgen Habermas's ideas, and wrote articles influenced by continental philosophy.[23]

Works

[edit]Books authored

[edit]- Putnam, H. (1971). Philosophy of Logic. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-04-160009-6.

- Putnam, H. (1975). Mathematics, Matter and Method. Philosophical Papers, vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20665-5. OCLC 59168146. 2nd. ed., 1985 paperback: ISBN 0-521-29550-5

- Putnam, H. (1975). Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 88-459-0257-9. 2003 paperback: ISBN 0-521-29551-3

- Putnam, H. (1978). Meaning and the Moral Sciences. Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 123–140. ISBN 978-0-710-08754-6. OCLC 318417931.

- Putnam, H. (1981). Reason, Truth, and History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23035-3. OCLC 442822274. 2004 paperback: ISBN 0-521-29776-1

- Putnam, H. (1983). Realism and Reason. Philosophical Papers, vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24672-9. OCLC 490070776. 2002 paperback: ISBN 0-521-31394-5

- Putnam, H. (1987). The Many Faces of Realism. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court. ISBN 0-8126-9043-5.

- Putnam, H. (1988). Representation and Reality. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-66074-7. OCLC 951364040.

- Putnam, H. (1990). Conant, J. F. (ed.). Realism with a Human Face. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-74945-0. OCLC 1014989000.

- Putnam, H. (1992). Renewing Philosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-76094-8.

- Putnam, H.; Cohen, Ted; Guyer, Paul, eds. (1993). Pursuits of Reason: Essays in Honor of Stanley Cavell. Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 0-89672-266-X.

- Putnam, H. (1994). Conant, J. F. (ed.). Words and Life. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-95607-9.

- Putnam, H. (1995). Pragmatism: An Open Question. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19343-X. Based on the Gifford Lectures that Putnam delivered at the University of St Andrews in 1990 and 1991.[104]

- Putnam, H. (1999). The Threefold Cord: Mind, Body, and World. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10286-5. OCLC 868429895.

- Putnam, H. (2001). Enlightenment and Pragmatism. Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum. ISBN 978-9-023-23739-6. OCLC 248668591.

- Putnam, H. (2002). The Collapse of the Fact/Value Dichotomy and Other Essays. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01380-8.

- Putnam, H. (2002). Ethics Without Ontology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01851-6.

- Putnam, H. (2008). Jewish Philosophy as a Guide to Life: Rosenzweig, Buber, Levinas, Wittgenstein. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35133-3. OCLC 819172227.

- Putnam, H. (2012). De Caro, M.; Macarthur, D. (eds.). Philosophy in an Age of Science. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05013-6. OCLC 913024858.

- Putnam, H. (2016). De Caro, Mario (ed.). Naturalism, Realism, and Normativity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-65969-8.

- Putnam, H.; Putnam, R. A. (2017). Macarthur, David (ed.). Pragmatism as a Way of Life: The Lasting Legacy of William James and John Dewey. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-96750-2.

Books edited

[edit]- Putnam, H. (1964). Benacerraf, Paul (ed.). Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. OCLC 1277244158. 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-521-29648-X

- Hempel, Carl G.; Putnam, H.; Essler, Wilhelm K., eds. (1983). Methodology, Epistemology, and Philosophy of Science: Essays in Honour of Wolfgang Stegmüller. Dordrecht: D. Reidel. ISBN 978-9-027-71646-0. OCLC 299388752.

- Essler, Wilhelm K.; Putnam, H.; Stegmüller, Wolfgang, eds. (1985). Epistemology, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science: Essays in Honour of Carl G. Hempel. Dordrecht: D. Reidel. OCLC 793401994.

Select papers, book chapters and essays

[edit]- .Putnam, H. (March 1967). "The 'Innateness Hypothesis' and Explanatory Models in Linguistics". Synthese. 17 (1): 12–22. doi:10.1007/BF00485014. JSTOR 20114532. S2CID 17124615.

An exhaustive bibliography of Putnam's writings, compiled by John R. Shook, can be found in The Philosophy Of Hilary Putnam (2015).[105][106]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Pragmatism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hilary Putnam at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (1978). ""Realism and reason", Presidential Address to the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association, December 1976". Meaning and the Moral Sciences. Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 123–140. ISBN 978-0-710-08754-6. OCLC 318417931.

- ^ van Fraassen, Bas (1997). "Putnam's Paradox: Metaphysical Realism Revamped and Evaded" (PDF). Philosophical Perspectives. 11: 17–42. JSTOR 2216123.

- ^ a b c d e Casati, R. (2004). "Hillary Putnam". In Vattimo, Gianni (ed.). Enciclopedia Garzanti della Filosofia. Milan: Garzanti Editori. ISBN 88-11-50515-1.

- ^ a b Davis, M.; Putnam, H (1960). "A computing procedure for quantification theory". Journal of the ACM. 7 (3): 201–215. doi:10.1145/321033.321034. S2CID 31888376.

- ^ Matiyesavic, Yuri (1993). Hilbert's Tenth Problem. Cambridge: MIT. ISBN 0-262-13295-8.

- ^ a b c d King, P. J. (2004). One Hundred Philosophers: The Life and Work of the World's Greatest Thinkers. Barron's. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-764-12791-5. OCLC 56593946.

- ^ Ritchie, Jack (June 2002). "TPM: Philosopher of the Month". Archived from the original on July 9, 2011.

- ^ LeDoux, J. (2002). The Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are. New York: Viking Penguin. ISBN 88-7078-795-8.

- ^ Horst, Steven (1999). "Symbols and Computation A Critique of the Computational Theory of Mind". Minds and Machines. 9 (3): 347–381. doi:10.1023/A:1008351818306.

- ^ a b c d e Clark, Peter; Hale, Bob, eds. (1995). Reading Putnam. Cambridge (Massachusetts), Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19995-3. OCLC 35303308.

- ^ a b c d Colyvan, Mark (Spring 2019). "Indispensability Arguments in the Philosophy of Mathematics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b Putnam, H. (1964). Benacerraf, Paul (ed.). Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. OCLC 1277244158. 2nd ed., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- ^ a b c d Putnam, H. (1981). "Brains in a vat" (PDF). Reason, Truth, and History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23035-3. OCLC 442822274. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2021. reprinted in DeRose, K.; Warfield, T. A., eds. (1999). Skepticism: A Contemporary Reader. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-11826-1. OCLC 1100897197.

- ^ a b Putnam, H. (1990). Conant, J. F. (ed.). Realism with a Human Face. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-74945-0. OCLC 1014989000.

- ^ Putnam, H. (2012). "From Quantum Mechanics to Ethics and Back Again". In De Caro, M.; Macarthur, D. (eds.). Philosophy in an Age of Science. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05013-6. OCLC 913024858.

- ^ a b c d e Putnam, Hilary (2015). Auxier, R. E.; Anderson, D. R.; Hahn, L. E. (eds.). The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9898-5. OCLC 921843436.

- ^ a b c d Foley, M. (2003). Confronting the War Machine: Draft Resistance during the Vietnam War. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2767-3.

- ^ a b c Baghramian, Maria (2012). "Introduction: A life in philosophy". In Baghramian, M. (ed.). Reading Putnam. New York: Routledge. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-0-415-53007-1. OCLC 809409617.

- ^ Wolfe, Bertram David (1965). Strange Communists I Have Known. Stein and Day. p. 79. OCLC 233981919.

- ^ Barsky, Robert F. (1997). "2: Undergraduate Years. A Very Powerful Personality". Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02418-1. OCLC 760607694. Archived from the original on November 6, 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hickey, L. P. (2009). Hilary Putnam. London, New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-847-06076-1. OCLC 1001716818.

- ^ Putnam, H. (1990). The Meaning of the Concept of Probability in Application to Finite Sequences. New York: Garland. ISBN 978-0-824-03209-8. OCLC 463716809.

- ^ a b c O'Grady, Jane (March 14, 2016). "Hilary Putnam obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ^ Marquard, Bryan (May 20, 2019). "Ruth Anna Putnam, Wellesley College philosophy professor, dies at 91". Boston Globe. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Wertheimer, L. K. (July 30, 2006). "Finding My Religion". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter P" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ Epps, G. (April 14, 1971). "Faculty Will Vote on New Procedures for Discipline". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ Thomas, E. W. (May 28, 1971). "Putnam Says Dunlop Threatens Radicals". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ "NYT correction, March 6, 2005". The New York Times. March 6, 2005. Retrieved August 1, 2006.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- ^ "The Spinoza Chair". Department of Philosophy. University of Amsterdam. 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ "Hilary Putnam: The Chosen People". Boston Review. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ "Hilary Putnam awarded The Rolf Schock Prize in Logic and Philosophy". The Philosopher's Eye. April 12, 2011. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016.

- ^ Fike, Katie (October 5, 2015). "Harvard's Hilary Putnam Awarded Pitt's Nicholas Rescher Prize". University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

- ^ Weber, B. (March 17, 2016). "Hilary Putnam, Giant of Modern Philosophy, Dies at 89". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Bickle, John (Fall 2006). "Multiple Realizability". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b c d e f Putnam, H. (1975). Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers, vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 88-459-0257-9.

- ^ a b c Shapiro, Lawrence A. (2000). "Multiple Realizations". The Journal of Philosophy. 97 (12): 635–654. doi:10.2307/2678460. ISSN 0022-362X. JSTOR 2678460.

- ^ Fodor, J. (1974). "Special Sciences". Synthese. 28: 97–115. doi:10.1007/BF00485230. JSTOR 20114958. S2CID 46979938.

- ^ Shapiro, Lawrence A. (2004). "The Multiple Realizability Thesis: Significance, Scope, and Support". The Mind Incarnate. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 1–33. ISBN 9780262693301.

- ^ a b Bechtel, William; Mundale, Jennifer. "Multiple Realizability Revisited". Philosophy of Science. 66 (2): 175–207. doi:10.1086/392683. JSTOR 188642. S2CID 122093404.

- ^ Kim, Sungsu (2002). "Testing Multiple Realizability: A Discussion of Bechtel and Mundale". Philosophy of Science. 69 (4): 606–610. doi:10.1086/344623. S2CID 120615475.

- ^ Kim, Jaegwon (March 1992). "Multiple Realizability and the Metaphysics of Reduction". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 52: 1–26. doi:10.2307/2107741. JSTOR 2107741.

- ^ Lewis, David (1969). "Review of Art, Mind, and Religion". Journal of Philosophy. 66: 23–35. doi:10.2307/2024154. JSTOR 2024154.

- ^ Richardson, Robert (1979). "Functionalism and Reductionism". Philosophy of Science. 46 (4): 533–558. doi:10.1086/288895. JSTOR 187248. S2CID 171075636.

- ^ Churchland, Patricia (1986). Neurophilosophy: Toward a unified science of the mind-brain. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03116-5. OCLC 299398803.

- ^ Davis, J. B. (2003). The Theory of the Individual in Economics: Identity and Value. Oxford: Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-415-20219-0. OCLC 779084377.

- ^ Block, Ned (2007). "What is Functionalism" (PDF). Consciousness, Function, and Representation. MIT Press. pp. 27–44. ISBN 978-0-262-02603-1. OCLC 494256364.

- ^ Hacking, Ian (May 4, 1989). "Putnam's Change of Mind". London Review of Books. Vol. 11, no. 9. ISSN 0260-9592. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

- ^ Hannon, Barbara (1993). "Review of Representation and Reality". Noûs. 27 (1): 102–106. doi:10.2307/2215905. ISSN 0029-4624. JSTOR 2215905.

- ^ a b Putnam, H. (1999). The Threefold Cord: Mind, Body, and World. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10286-5. OCLC 868429895.

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (1988). Representation and Reality. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-66074-7. OCLC 951364040.

- ^ a b Marhaba, S. (2004). "Funzionalismo". In Vattimo, G.; Chiurazzi, G. (eds.). Enciclopedia Garzanti della Filosofia. Milan: Garzanti Editore. ISBN 88-11-50515-1.

- ^ Levin, Janet (Fall 2004). "Functionalism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b c Putnam, Hilary (October 30, 2015). "What Wiki Doesn't Know About Me". Sardonic comment. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ Searle, John (1980). "Minds, Brains and Programs". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 3 (3): 417–424. doi:10.1017/S0140525X00005756. S2CID 55303721. Archived from the original on February 21, 2001.

- ^ Block, Ned (1978). "Troubles With Functionalism". In Savage, C. W. (ed.). Perception and Cognition: Issues in the Foundations of Psychology, Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-816-60841-6. OCLC 1123818208.

- ^ Aranyosi, István (2013). "Semantic Externalism". The Peripheral Mind: Philosophy of Mind and the Peripheral Nervous System. Oxford University Press. pp. 77–101. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199989607.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-998960-7.

- ^ Rowlands, Mark; Lau, Joe; Deutsch, Max (December 10, 2020). "Externalism About the Mind". In Zalta, E. N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2020 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ Stalnaker, Robert (1993). "Twin Earth Revisited". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 93: 297–311. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/93.1.297. ISSN 0066-7374. JSTOR 4545179.

- ^ Davidson, D. (2001). Subjective, Intersubjective, Objective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 177–192. ISBN 88-7078-832-6.

- ^ Zelinsky-Wibbelt, C., Discourse and the Continuity of Reference: Representing Mental Categorization (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011) p. 33.

- ^ Dell'Utri, Massimo, ed. (2002). Olismo. Macerata: Quodlibet. ISBN 88-86570-85-6.

- ^ Fodor, J.; Lepore, E. (1992). Holism: A Shopper's Guide. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-18192-7. OCLC 644785316.

- ^ Dummett, Michael (1991). The Logical Basis of Metaphysics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-53785-9. OCLC 21907992.

- ^ Penco, Carlo (2002). "Olismo e Molecularismo". In Dell'Utri, Massimo (ed.). Olismo. Macerata: Quodlibet. ISBN 88-86570-85-6.

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (1971). Philosophy of Logic. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780061360428.

- ^ a b Hill, C. S., ed. (1992). The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. OCLC 60085231.

- ^ Marcus, Russell. "The Indispensability Argument in the Philosophy of Mathematics". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved August 23, 2022.

- ^ Hellman, Geoffrey; Cook, Roy T. (2018). Hilary Putnam on Logic and Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-96273-3. OCLC 1040620232.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Andrew Wiles", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ Cooper, S. Barry (2004). Computability Theory. Chapman and Hall/CRC Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-1-584-88237-4. OCLC 318382229.

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (1963). "A note on constructible sets of integers". Notre Dame J. Formal Logic. 4 (4): 270–273. doi:10.1305/ndjfl/1093957652.

- ^ Boolos, George; Putnam, Hilary (1968). "Degrees of unsolvability of constructible sets of integers". Journal of Symbolic Logic. 33 (4). The Journal of Symbolic Logic, Vol. 33, No. 4: 497–513. doi:10.2307/2271357. JSTOR 2271357. S2CID 28883741.

- ^ Boyd, Richard; Hensel, Gustav; Putnam, Hilary (1969). "A recursion-theoretic characterization of the ramified analytical hierarchy". Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 141. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, Vol. 141: 37–62. doi:10.2307/1995087. JSTOR 1995087.

- ^ a b McKinsey, Michael (Summer 2018). "Skepticism and Content Externalism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Putnam, H. (1983). Realism and Reason. Philosophical Papers, vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24672-9. OCLC 490070776.

- ^ a b Wright, C. (1992). "On Putnam's Proof That We Are Not Brains-in-a-Vat". Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 92 (1): 67–94. doi:10.1093/aristotelian/92.1.67. JSTOR 4545146.

- ^ Dell'Utri, M. (1990). "Choosing Conceptions of Realism: the Case of the Brains in a Vat". Mind. 99 (393): 79–90. doi:10.1093/mind/XCIX.393.79. JSTOR 2254892.

- ^ a b Khlentzos, Drew. "Challenges to Metaphysical Realism". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2021 ed.).

- ^ Steinitz, Yuval (1994). "Brains in a Vat: Different Perspectives" (PDF). The Philosophical Quarterly. 44 (175): 213–222. doi:10.2307/2219742. JSTOR 2219742.

- ^ a b Künne, Wolfgang (2009). Conceptions of Truth. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928019-3.

- ^ Sosa, Ernest (December 1993). "Putnam's Pragmatic Realism". The Journal of Philosophy. 90 (12): 605–626. doi:10.2307/2940814. JSTOR 2940814.

Putnam argues against 'metaphysical realism' and in favor of his own 'internal (or pragmatic) realism.'

- ^ Putnam, H. (1987). The Many Faces of Realism. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court. ISBN 0-8126-9043-5.

- ^ a b Curtis Brown (1988). "Internal Realism: Transcendental Idealism?" (PDF). Midwest Studies in Philosophy. 12 (12): 145–55. doi:10.5840/msp19881238.

- ^ Devitt, Michael (1984). Realism and Truth. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 331. ISBN 978-0-691-07290-6. OCLC 10559172.

- ^ Goodman, N. (1983). Fact, Fiction, and Forecast. Cambridge, Massachusetts & London: Harvard University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-674-29071-6. OCLC 1090329720.

- ^ a b c Putnam, H. (1997). "A Half Century of Philosophy, Viewed from Within". Daedalus. 126 (1): 175–208. JSTOR 20027414.

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (September 1994). "The Dewey Lectures 1994: Sense, Nonsense, and the Senses: An Inquiry into the Powers of the Human Mind". The Journal of Philosophy. 91 (9): 445–518. doi:10.2307/2940978. JSTOR 2940978.

- ^ Pihlström, Sami (2013). "Neopragmatism". In Runehov, Anne L. C.; Oviedo, Lluis (eds.). Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions. Springer. pp. 1455–1465. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8265-8_1538. ISBN 978-1-4020-8264-1.

- ^ Reed, Edward (1996). The Necessity of Experience. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06668-6.

- ^ Putnam, Hilary (November 9, 2015). "Wiki Catches Up a Bit". Sardonic comment. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ Putnam, H. (2012). "How to Be a Sophisticated "Naive Realist"". In De Caro, M.; Macarthur, D. (eds.). Philosophy in an Age of Science. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05013-6. OCLC 913024858.

- ^ a b Putnam, Hilary (December 1, 2005). "A Philosopher Looks at Quantum Mechanics (Again)". The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 56 (4): 615–634. doi:10.1093/bjps/axi135. ISSN 0007-0882.

- ^ Gardner, Michael R. (1971). "Is Quantum Logic Really Logic?". Philosophy of Science. 38 (4): 508–529. doi:10.1086/288393. ISSN 0031-8248. JSTOR 186692. S2CID 120329154.

- ^ Bub, Jeffrey (1982). "Quantum Logic, Conditional Probability, and Interference". Philosophy of Science. 49 (3): 402–421. doi:10.1086/289068. ISSN 0031-8248. JSTOR 187282. S2CID 120818704.

- ^ Demopoulos, William (April 2010). "Effects and Propositions". Foundations of Physics. 40 (4): 368–389. arXiv:0809.0659. Bibcode:2010FoPh...40..368D. doi:10.1007/s10701-009-9321-x. ISSN 0015-9018. S2CID 119273606.

- ^ Hemmo, Meir; Pitowsky, Itamar (June 2007). "Quantum probability and many worlds". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics. 38 (2): 333–350. Bibcode:2007SHPMP..38..333H. doi:10.1016/j.shpsb.2006.04.005.

- ^ Gaynesford, R. M. de (2006). Hilary Putnam. McGill–Queen's University Press / Acumen. ISBN 978-1-844-65040-8. OCLC 224793821.

- ^ Bartlett, T. (September 10, 2017). "A Marriage of Minds: Hilary Putnam's most surprising philosophical shift began at home". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- ^ Reed, Edward (1997). "Defending Experience: A Philosophy For The Post-Modern World". The Genetic Epistemologist: The Journal of the Jean Piaget Society. 25 (3).

- ^ "Hilary Putnam". The Gifford Lectures. August 18, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Shook, John R. (May 18, 2015). "Bibliography of the Writings of Hilary Putnam" (PDF). In Auxier, Randall E.; Anderson, Douglas R.; Hahn, Lewis Edwin (eds.). The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam. Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9898-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 14, 2016.

- ^ Chang, Hasok (2018). "Review of The Philosophy of Hilary Putnam". The Philosophical Review. 127 (2): 240–247. doi:10.1215/00318108-4326677. ISSN 0031-8108. JSTOR 27130985 – via JSTOR.

Further reading

[edit]- Conant, James; Chakraborty, Sanjit, eds. (2022). Engaging Putnam. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-76916-6. OCLC 1302581520.

- Ben-Menahem, Y., ed. (2005). Hilary Putnam. Contemporary Philosophy in Focus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81311-2. OCLC 912352048.

External links

[edit]- Hilary Putnam's blog, Sardonic comment, as stated by Putnam in "Hookway and Quine", Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society, vol. 51, no. 4, 2015, pp. 495–507. doi:10.2979/trancharpeirsoc.51.4.07

- Hilary Putnam at PhilPapers

- Hilary Putnam at IMDb

- Hilary Putnam at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- London Review of Books contributor page

- Hilary Putnam: On Mind, Meaning and Reality Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Interview by Josh Harlan, The Harvard Review of Philosophy, Spring 1992.

- "To Think with Integrity" Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Hilary Putnam's Farewell Lecture, The Harvard Review of Philosophy, Spring 2000.

- A short film about the Putnam-Rorty debate and its influence on the pragmatist revival on YouTube

Quotations related to Hilary Putnam at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Hilary Putnam at Wikiquote

- 1926 births

- 2016 deaths

- 20th-century American Jews

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American mathematicians

- 20th-century American philosophers

- 20th-century American essayists

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American mathematicians

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century American philosophers

- 21st-century American essayists

- American male essayists

- American male non-fiction writers

- Analytic philosophers

- Central High School (Philadelphia) alumni

- Corresponding fellows of the British Academy

- Deaths from lung cancer in Massachusetts

- American epistemologists

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Harvard University alumni

- Harvard University Department of Philosophy faculty

- Jewish philosophers

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology faculty

- Mathematicians from Illinois

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Members of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts

- Metaphilosophers

- American metaphysicians

- Northwestern University faculty

- Ontologists

- American philosophers of education

- Philosophers of Judaism

- American philosophers of language

- American philosophers of logic

- American philosophers of mathematics

- American philosophers of mind

- American philosophers of science

- American philosophers of technology

- American philosophy academics

- American philosophy writers

- Pragmatists

- Princeton University faculty

- Scientists from Chicago

- University of California, Los Angeles alumni

- University of Pennsylvania alumni