Hemp

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a plant in the botanical class of Cannabis sativa cultivars grown specifically for industrial and consumable use. It can be used to make a wide range of products.[1] Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants[2] on Earth. It was also one of the first plants to be spun into usable fiber 50,000 years ago.[3] It can be refined into a variety of commercial items, including paper, rope, textiles, clothing, biodegradable plastics, paint, insulation, biofuel, food, and animal feed.[4][5]

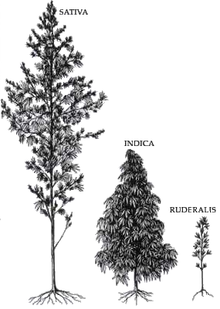

Although chemotype I cannabis and hemp (types II, III, IV, V) are both Cannabis sativa and contain the psychoactive component tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), they represent distinct cultivar groups, typically with unique phytochemical compositions and uses.[6] Hemp typically has lower concentrations of total THC and may have higher concentrations of cannabidiol (CBD), which potentially mitigates the psychoactive effects of THC.[7] The legality of hemp varies widely among countries. Some governments regulate the concentration of THC and permit only hemp that is bred with an especially low THC content into commercial production.[8][9]

Etymology

[edit]The etymology is uncertain but there appears to be no common Proto-Indo-European source for the various forms of the word; the Greek term κάνναβις (kánnabis) is the oldest attested form, which may have been borrowed from an earlier Scythian or Thracian word.[10][11] Then it appears to have been borrowed into Latin, and separately into Slavic and from there into Baltic, Finnish, and Germanic languages.[12]

In the Germanic languages, following Grimm's law, the "k" would have changed to "h" with the first Germanic sound shift,[10][13] giving Proto-Germanic *hanapiz, after which it may have been adapted into the Old English form, hænep, henep.[10] Barber (1991) however, argued that the spread of the name "kannabis" was due to its historically more recent plant use, starting from the south, around Iran, whereas non-THC varieties of hemp are older and prehistoric.[12] Another possible source of origin is Assyrian qunnabu, which was the name for a source of oil, fiber, and medicine in the 1st millennium BC.[12]

Cognates of hemp in other Germanic languages include Dutch hennep, Danish and Norwegian hamp, Saterland Frisian Hoamp, German Hanf, Icelandic hampur and Swedish hampa. In those languages "hemp" can refer to either industrial fiber hemp or narcotic cannabis strains.[10]

Uses

[edit]

Hemp is used to make a variety of commercial and industrial products, including rope, textiles, clothing, shoes, food, paper, bioplastics, insulation, and biofuel.[4] The bast fibers can be used to make textiles that are 100% hemp, but they are commonly blended with other fibers, such as flax, cotton or silk, as well as virgin and recycled polyester, to make woven fabrics for apparel and furnishings. The inner two fibers of the plant are woodier and typically have industrial applications, such as mulch, animal bedding, and litter. When oxidized (often erroneously referred to as "drying"), hemp oil from the seeds becomes solid and can be used in the manufacture of oil-based paints, in creams as a moisturizing agent, for cooking, and in plastics. Hemp seeds have been used in bird feed mix as well. A survey in 2003 showed that more than 95% of hemp seed sold in the European Union was used in animal and bird feed.[14]

Food

[edit]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 2,451 kJ (586 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

4.67 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 1.50 g 0.07 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 4.0 g (around 20 g when whole) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

48.75 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturated | 4.600 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trans | 0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 5.400 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 38.100 g 9.301 g 28.698 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

31.56 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tryptophan | 0.369 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Threonine | 1.269 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isoleucine | 1.286 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leucine | 2.163 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lysine | 1.276 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Methionine | 0.933 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cystine | 0.672 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phenylalanine | 1.447 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tyrosine | 1.263 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valine | 1.777 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arginine | 4.550 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Histidine | 0.969 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alanine | 1.528 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aspartic acid | 3.662 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glutamic acid | 6.269 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glycine | 1.611 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proline | 1.597 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serine | 1.713 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 4.96 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cholesterol | 0 mg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[15] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[16] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hemp seeds can be eaten raw, ground into hemp meal, sprouted or made into dried sprout powder. Hemp seeds can also be made into a slurry used for baking or for beverages, such as hemp milk and tisanes.[17] Hemp oil is cold-pressed from the seed and is high in unsaturated fatty acids.[18]

In the UK, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs treats hemp as a purely non-food crop, but with proper licensing and proof of less than 0.3% THC concentration, hemp seeds can be imported for sowing or for sale as a food or food ingredient.[19] In the US, hemp can be used legally in food products and, as of 2000[update], was typically sold in health food stores or through mail order.[18]

-

Whole hemp seeds

-

Hulled hemp seeds

Nutrition

[edit]A 100-gram (3+1⁄2-ounce) portion of hulled hemp seeds supplies 2,451 kilojoules (586 kilocalories) of food energy. They contain 5% water, 5% carbohydrates, 49% total fat, and 31% protein.[20]

The share of protein obtained from the hemp seeds can be increased in by processing the seeds, such as by dehulling the seeds, or by using the meal or cake (also called hemp seed flour),[21] that is, the remaining fraction of hemp seed obtained after expelling its oil fraction.[22][23] The proteins are mostly located in the inner layer of the seed, whereas the hull is poor in proteins, as it mostly contains the fiber.[23][24]

Hemp seeds are notable in providing 64% of the Daily Value (DV) of protein per 100-gram serving.[20] The three main proteins in hemp seeds are edestin (83% of total protein content), albumin (13%) and ß-conglycinin (up to 5%).[25][23] Hemp seed proteins are highly digestible compared to soy proteins when untreated (unheated).[26][23] The amino acid profile of hemp seeds is comparable to the profiles of other protein-rich foods, such as meat, milk, eggs, and soy.[27][24][28] Protein digestibility-corrected amino acid scores were 0.49–0.53 for whole hemp seed, 0.46–0.51 for hemp seed meal, and 0.63–0.66 for hulled hemp seed.[21][29] The most abundant amino acid in hemp seed is glutamic acid (3.74–4.58% of whole seed) followed by arginine (2.28–3.10% of whole seed).[22][23][24] The whole hemp seed can be considered a rich-protein source containing a protein amount higher or similar than other protein-rich products, such as quinoa (13.0%), chia seeds (18.2–19.7%), buckwheat seeds (27.8%) and linseeds (20.9%). Nutritionally, the protein fraction of hemp seed is highly digestible comparing to other plant-based proteins such as soy protein. Hemp seed protein has a good profile of essential amino acids, still, this profile of amino acids is inferior to that of soy or casein.[23][24][30]

Hemp seeds are a rich source of dietary fiber (20% DV), B vitamins, and the dietary minerals manganese (362% DV), phosphorus (236% DV), magnesium (197% DV), zinc (104% DV), and iron (61% DV). About 73% of the energy in hemp seeds is in the form of fats and essential fatty acids,[20] mainly polyunsaturated fatty acids, linoleic, oleic, and alpha-linolenic acids.[24][28] The ratio of the 38.100 grams of polyunsaturated fats per 100 grams is 9.301 grams of omega-3 to 28.698 grams of omega-6.[31] Typically, the portion suggested on packages for an adult is 30 grams, approximately three tablespoons.[31]

With its gluten content as low as 4.78 ppm, hemp is attracting attention as a gluten-free (<20 ppm) food material.[25]

Despite the rich nutrient content of hemp seeds, the seeds contain antinutritional compounds, including phytic acid,[32] trypsin inhibitors, and tannins, in statistically significant concentrations.[26][33]

Storage

[edit]Hemp oil oxidizes and turns rancid within a short period of time if not stored properly;[18] its shelf life is extended when it is stored in a dark airtight container and refrigerated. Both light and heat can degrade hemp oil.

Fiber

[edit]Hemp fiber has been used extensively throughout history, with production climaxing soon after being introduced to the New World. For centuries, items ranging from rope, to fabrics, to industrial materials were made from hemp fiber. Hemp was also commonly used to make sail canvas. The word "canvas" is derived from the word cannabis.[34][35] Pure hemp has a texture similar to linen.[36] Because of its versatility for use in a variety of products, today hemp is used in a number of consumer goods, including clothing, shoes, accessories, dog collars, and home wares. For clothing, in some instances, hemp is mixed with lyocell.[37] Its benefits in terms for sustainability also increase its appeal in industries, such as the clothing industry.[38][39]

-

Hemp stem showing fibers

-

100% hemp fabric

-

Hemp dress

-

Hemp dress

-

Hemp shorts

-

Hemp sack

-

Hemp shoes

Building material

[edit]Hemp as a building construction material provides solutions to a variety of issues facing current building standards. Its light weight, mold resistance, breathability, etc. makes hemp products versatile in a multitude of uses.[40] Following the co-heating tests of NNFCC Renewable House at the Building Research Establishment (BRE), hemp is reported to be a more sustainable material of construction in comparison to most building methods used today.[41] In addition, its practical use in building construction could result in the reduction of both energy consumption costs and the creation of secondary pollutants.[41]

In 2022, hemp-lime, also known as hempcrete, was accepted as a building material, along with methodologies for its use, by the International Code Council,[42] and was included in the 2024 edition of the International Residential Code as an appendix: "Appendix BL Hemp-Lime (Hempcrete) Construction".[43] This inclusion in the IRC model code is expected to promote expansion of the use and legitimacy of hemp-lime in construction in the United States.[44]

The hemp market was at its largest during the 17th century. In the 19th century and onward, the market saw a decline during its rapid illegalization in many countries.[45] Hemp has resurfaced in green building construction, primarily in Europe.[46] The modern-day disputes regarding the legality of hemp lead to its main disadvantages: importing and regulating costs. Final Report on the Construction of the Hemp Houses at Haverhill, UK conducts that hemp construction exceeds the cost of traditional building materials by £48per square meter.[46]

Currently, the University of Bath researches the use of hemp-lime panel systems for construction. Funded by the European Union, the research tests panel design within their use in high-quality construction, on site assembly, humidity and moisture penetration, temperature change, daily performance and energy saving documentations.[47] The program, focusing on Britain, France, and Spain markets aims to perfect protocols of use and application, manufacturing, data gathering, certification for market use, as well as warranty and insurance.[47]

The most common use of hemp-lime in building is by casting the hemp-hurd and lime mix while wet around a timber frame with temporary shuttering and tamping the mix to form a firm mass. After the removal of the temporary shuttering, the solidified hemp mix is then ready to be plastered with lime plaster.[48]

Sustainability

[edit]Hemp is classified under the green category of building design, primarily due to its positive effects on the environment.[49] A few of its benefits include but are not limited to the suppression of weed growth, anti-erosion, reclamation properties, and the ability to remove poisonous substances and heavy metals from soil.[49]

The use of hemp is beginning to gain popularity alongside other natural materials. This is because cannabis processing is done mechanically with minimal harmful effects on the environment. A part of what makes hemp sustainable is its minimal water usage and non-reliance on pesticides for proper growth. It is recyclable, non-toxic, and biodegradable, making hemp a popular choice in green building construction.[49]

Hemp fiber is known to have high strength and durability, and has been known to be a good protector against vermin. The fiber has the capability to reinforce structures by embossing threads and cannabis shavers. Hemp has been involved more recently in the building industry, producing building construction materials including insulation, hempcrete, and varnishes.[40][50][51][52][53][54]

Hemp made materials have low embodied energy. The plant has the ability to absorb large amounts of CO2, providing air quality, thermal balance, creating a positive environmental impact.[50]

Hemp's properties allow mold resistance, and its porous materiality makes the building materials made of it breathable. In addition hemp possesses the ability to absorb and release moisture without deteriorating. Hemp can be non-flammable if mixed with lime and could be applied on numerous aspects of the building (wall, roofs, etc.) due to its lightweight properties.[49][50]

Insulation

[edit]Hemp is commonly used as an insulation material. Its flexibility and toughness during compression allows for easier implementation within structural framing systems. The insulation material could also be easily adjusted to different sizes and shapes by being cut during the installation process. The ability to not settle and therefore avoiding cavity developments lowers its need for maintenance.[54]

Hemp insulation is naturally lightweight and non-toxic, allowing for an exposed installation in a variety of spaces, including flooring, walling, and roofing. Compared to mineral insulation, hemp absorbs roughly double the amount of heat and could be compared to wood, in some cases even overpassing some of its types.[54]

Hemp insulation's porous materiality allows for air and moisture penetration, with a bulk density going up to 20% without losing any thermal properties. In contrast, the commonly used mineral insulation starts to fail after 2%. The insulation evenly distributes vapor and allows for air circulation, constantly carrying out used air and replacing with fresh. Its use on the exterior of the structure, overlaid with breathable water-resistive barriers, eases the withdrawal of moisture from within the wall structure.[54]

In addition, the insulation doubles as a sound barrier, weakening airborne sound waves passing through it.[54]

Hempcrete

[edit]In addition to the CO2 absorbed during its growth period, hemp-lime, also known as hempcrete, continues absorption during the curing process. The mixture hardens when the silica contained in hemp shives mixes with hydraulic lime, resulting in the mineralization process called "carbonation".[dubious – discuss].[53][55]

Though not a load-bearing material,[56] hempcrete is most commonly used as infill in building construction due to its light weight (roughly seven times lighter than common concrete) and vapor permeability.[57] The building material is made of hemp hurds (shiv or shives), hydraulic lime, and water mixed in varying ratios.[52] The mix depends on the use of the material within the structure and could differ in physical properties. Surfaces such as flooring interact with a multitude of loads and would have to be more resistive, while walls and roofs are required to be more lightweight.[52] The application of this material in construction requires minimal skill.[52]

Hempcrete can be formed in-situ or formed into blocks. Such blocks are not strong enough to be used for structural elements and must be supported by brick, wood, or steel framing.[41] In the end of the twentieth century, during his renovation of Maison de la Turquie in Nogent-sur-Seine, France, Charles Rasetti first invented and applied the use of hempcrete in construction.[58] Shortly after, in the 2000s, Modece Architects used hemp-lime for test designs in Haverhill.[59] The dwellings were studied and monitored for comparison with other building performances by BRE. Completed in 2009, the Center for the Built Environment's Renewable House was found to be among the most technologically advanced structures made of hemp-based material. A year later the first home made of hemp-based materials was completed in Asheville, North Carolina, US.[60]

Oils and varnishes

[edit]Cannabis seeds have high-fat content and contain 30-35% of fatty acids. The extracted oil is suited for a variety of construction applications.[50] The biodegradable hemp oil acts as a wood varnish, protecting flooring from mold, pests, and wear. Its use prevents the water from penetrating the wood while still allowing air and vapor to pass through.[40] Its most common use can be seen in wood framing construction, one of the most common construction methods in the world. Because of its low UV-resistant rating, the finish is most often used indoors, on surfaces such as flooring and wood paneling.[54][40]

Plaster

[edit]Hemp-based insulating plaster is created by combining hemp fibers with calcium lime and sand. This material, when applied on internal walls, ceilings, and flooring, can be layered up to ten centimeters in thickness. Its porous materiality allows the created plaster to regulate air humidity and evenly distribute it.[40] The gradual absorption and release of water prevent the material from cracking and breaking apart.[61][40] Similar to high-density fiber cement, hemp plaster can naturally vary in color and be manually pigmented.[62]

Ropes and strands

[edit]Hemp ropes can be woven in various diameters, possessing high amounts of strength making them suitable for a variety of uses for building construction purposes.[53] Some of these uses include installation of frames in building openings and connection of joints. The ropes also used in bridge construction, tunnels, traditional homes, etc.[53] One of the earliest examples of hemp rope and other textile use can be traced back to 1500 BC Egypt.[63]

Plastics

[edit]Cannabis geotextiles could be put in both wet and dry conditions. Hemp-based bioplastic is a biodegradable alternative to regular plastic and can potentially replace polyvinyl chloride (PVC), a material used for plumbing pipes.[53]

Wood

[edit]Hemp growth lasts roughly 100 days, a much faster time period than an average tree used for construction purposes. While dry, the fibers could be pressed into tight wood alternatives to wood-frame construction, wall/ceiling paneling, and flooring. As an addition, hemp is flexible and versatile allowing it to be used in a greater number of ways than wood.[40] Similarly, hemp wood could also be made of recycled hemp-based paper.[64]

-

Hemp fiber board

-

Hemp thermal insulation

-

Hemp interior thermal insulation blocks

-

Hemp acoustic ceiling insulation

-

Concrete block made with hemp in France

-

Highland Hemp House finished hempcrete

-

Hemp sound insulation brick

-

Hemp rope used in construction

-

Sustainable construction in practice

-

House that used hemp as one of its building materials

-

Hemp wall

Composite materials

[edit]This section needs expansion with: what are the comparative economics of using hemp vs. alternative materials in some of these applications?. You can help by adding to it. (March 2024) |

A mixture of fiberglass, hemp fiber, kenaf, and flax has been used since 2002 to make composite panels for automobiles.[65] The choice of which bast fiber to use is primarily based on cost and availability. Various car makers are beginning to use hemp in their cars, including Audi, BMW, Ford, GM, Chrysler, Honda, Iveco, Lotus, Mercedes, Mitsubishi, Porsche, Saturn, Volkswagen[66] and Volvo. For example, the Lotus Eco Elise[67] and the Mercedes C-Class both contain hemp (up to 20 kg in each car in the case of the latter).[68]

-

Hemp plastic interior of a car door

-

Hemp plastic automobile glove box

-

Hemp plastic column, automobile

-

Hemp composite sink basin

Paper

[edit]Hemp paper are paper varieties consisting exclusively or to a large extent from pulp obtained from fibers of industrial hemp. The products are mainly specialty papers such as cigarette paper,[69] banknotes and technical filter papers.[70] Compared to wood pulp, hemp pulp offers a four to five times longer fiber, a significantly lower lignin fraction as well as a higher tear resistance and tensile strength. However, production costs are about four times higher than for paper from wood,[71] since the infrastructure for using hemp is underdeveloped. If the paper industry were to switch from wood to hemp for sourcing its cellulose fibers, the following benefits could be utilized:

- Hemp yields three to four times more usable fiber per hectare per annum than forests, and hemp does not need pesticides or herbicides.[72]

- Hemp has a much faster crop yield. It takes about 3–4 months for hemp stalks to reach maturity,[73] while trees can take between 20 and 80 years. Not only does hemp grow at a faster rate, but it also contains a high level of cellulose.[74] This quick return means that paper can be produced at a faster rate if hemp were used in place of wood.

- Hemp paper does not require the use of toxic bleaching or as many chemicals as wood pulp because it can be whitened with hydrogen peroxide. This means using hemp instead of wood for paper would end the practice of poisoning Earth's waterways with chlorine or dioxins from wood paper manufacturing.[75]

- Hemp paper can be recycled up to 8 times, compared to just 3 times for paper made from wood pulp.[75]

- Compared to its wood pulp counterpart, paper from hemp fibers resists decomposition and does not yellow or brown with age.[75] It is also one of the strongest natural fibers in the world[76] - one of the reasons for its longevity and durability.

- Several factors favor the increased use of wood substitutes for paper, especially agricultural fibers such as hemp. Deforestation, particularly the destruction of old growth forests, and the world's decreasing supply of wild timber resources are today major ecological concerns. Hemp's use as a wood substitute will contribute to preserving biodiversity.[76]

However, hemp has had a hard time competing with paper from trees or recycled newsprint. Only the outer part of the stem consists mainly of fibers which are suitable for the production of paper. Numerous attempts have been made to develop machines that efficiently and inexpensively separate useful fibers from less useful fibers, but none have been completely successful. This has meant that paper from hemp is still expensive compared to paper from trees.

Jewelry

[edit]

Hemp jewelry is the product of knotting hemp twine through the practice of macramé. Hemp jewelry includes bracelets, necklaces, anklets, rings, watches, and other adornments. Some jewelry features beads made from crystals, glass, stone, wood and bones. The hemp twine varies in thickness and comes in a variety of colors. There are many different stitches used to create hemp jewelry, however, the half knot and full knot stitches are most common.

Cordage

[edit]

Hemp rope was used in the age of sailing ships, though the rope had to be protected by tarring, since hemp rope has a propensity for breaking from rot, as the capillary effect of the rope-woven fibers tended to hold liquid at the interior, while seeming dry from the outside.[77] Tarring was a labor-intensive process, and earned sailors the nickname "Jack Tar". Hemp rope was phased out when manila rope, which does not require tarring, became widely available. Manila is sometimes referred to as Manila hemp, but is not related to hemp; it is abacá, a species of banana.

Animal bedding

[edit]

Hemp shives are the core of the stem, hemp hurds are broken parts of the core. In the EU, they are used for animal bedding (horses, for instance), or for horticultural mulch.[78] Industrial hemp is much more profitable if both fibers and shives (or even seeds) can be used.

Water and soil purification

[edit]Hemp can be used as a "mop crop" to clear impurities out of wastewater, such as sewage effluent, excessive phosphorus from chicken litter, or other unwanted substances or chemicals. Additionally, hemp is being used to clean contaminants at the Chernobyl nuclear disaster site, by way of a process which is known as phytoremediation – the process of clearing radioisotopes and a variety of other toxins from the soil, water, and air.[79]

Weed control

[edit]Hemp crops are tall, have thick foliage, and can be planted densely, and thus can be grown as a smother crop to kill tough weeds.[80] Using hemp this way can help farmers avoid the use of herbicides, gain organic certification, and gain the benefits of crop rotation. However, due to the plant's rapid and dense growth characteristics, some jurisdictions consider hemp a prohibited and noxious weed, much like Scotch Broom.[81]

-

The dense growth of hemp helps kill weeds, even thistle.

Biofuels

[edit]

Biodiesel can be made from the oils in hemp seeds and stalks; this product is sometimes called "hempoline".[82] Alcohol fuel (ethanol or, less commonly, methanol) can be made by fermenting the whole plant.

Filtered hemp oil can be used directly to power diesel engines. In 1892, Rudolf Diesel invented the diesel engine, which he intended to power "by a variety of fuels, especially vegetable and seed oils, which earlier were used for oil lamps, i.e. the Argand lamp".[83][84][85]

Production of vehicle fuel from hemp is very small. Commercial biodiesel and biogas is typically produced from cereals, coconuts, palm seeds, and cheaper raw materials like garbage, wastewater, dead plant and animal material, animal feces and kitchen waste.[86]

Processing

[edit]Separation of hurd and bast fiber is known as decortication. Traditionally, hemp stalks would be water-retted first before the fibers were beaten off the inner hurd by hand, a process known as scutching. As mechanical technology evolved, separating the fiber from the core was accomplished by crushing rollers and brush rollers, or by hammer-milling, wherein a mechanical hammer mechanism beats the hemp against a screen until hurd, smaller bast fibers, and dust fall through the screen. After the Marijuana Tax Act was implemented in 1938, the technology for separating the fibers from the core remained "frozen in time". Recently, new high-speed kinematic decortication has come about, capable of separating hemp into three streams; bast fiber, hurd, and green microfiber.

Only in 1997, did Ireland, parts of the Commonwealth and other countries begin to legally grow industrial hemp again. Iterations of the 1930s decorticator have been met with limited success, along with steam explosion and chemical processing known as thermomechanical pulping.[citation needed]

Cultivation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

Hemp is usually planted between March and May in the northern hemisphere, between September and November in the southern hemisphere.[87] It matures in about three to four months, depending on various conditions.

Millennia of selective breeding have resulted in varieties that display a wide range of traits; e.g. suited for particular environments/latitudes, producing different ratios and compositions of terpenoids and cannabinoids (CBD, THC, CBG, CBC, CBN...etc.), fiber quality, oil/seed yield, etc. Hemp grown for fiber is planted closely, resulting in tall, slender plants with long fibers.[88]

The use of industrial hemp plant and its cultivation was commonplace until the 1900s when it was associated with its genetic sibling a.k.a. Drug-Type Cannabis species (which contain higher levels of psychoactive THC). Influential groups misconstrued hemp as a dangerous "drug",[89] even though hemp is not a recreational drug and has the potential to be a sustainable and profitable crop for many farmers due to hemp's medical, structural and dietary uses.[90][91] In the United States, the public's perception of hemp as marijuana has blocked hemp from becoming a useful crop and product,"[90] in spite of its vital importance prior to World War II.[91]

Ideally, according to Britain's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, the herb should be desiccated and harvested toward the end of flowering. This early cropping reduces the seed yield but improves the fiber yield and quality.[92]

The seeds are sown with grain drills or other conventional seeding equipment to a depth of 13 to 25 mm (1⁄2 to 1 in). Greater seeding depths result in increased weed competition. Nitrogen should not be placed with the seed, but phosphate may be tolerated. The soil should have available 89 to 135 kg/ha of nitrogen, 46 kg/ha phosphorus, 67 kg/ha potassium, and 17 kg/ha sulfur. Organic fertilizers such as manure are one of the best methods of weed control.[93]

Cultivars

[edit]In contrast to cannabis for medical use, varieties grown for fiber and seed have less than 0.3% THC and are unsuitable for producing hashish and marijuana.[94] Present in industrial hemp, cannabidiol is a major constituent among some 560 compounds found in hemp.[95]

Cannabis sativa L. subsp. sativa var. sativa is the variety grown for industrial use, while C. sativa subsp. indica generally has poor fiber quality and female buds from this variety are primarily used for recreational and medicinal purposes. The major differences between the two types of plants are the appearance, and the amount of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) secreted in a resinous mixture by epidermal hairs called glandular trichomes, although they can also be distinguished genetically.[94][96] Oilseed and fiber varieties of Cannabis approved for industrial hemp production produce only minute amounts of this psychoactive drug, not enough for any physical or psychological effects. Typically, hemp contains below 0.3% THC, while cultivars of Cannabis grown for medicinal or recreational use can contain anywhere from 2% to over 20%.[97]

-

Cannabis sativa stem

-

Hemp strains USO-xx and Zolotoniski-xx

Harvesting

[edit]Smallholder plots are usually harvested by hand. The plants are cut at 2 to 3 cm above the soil and left on the ground to dry. Mechanical harvesting is now common, using specially adapted cutter-binders or simpler cutters.

The cut hemp is laid in swathes to dry for up to four days. This was traditionally followed by retting, either water retting (the bundled hemp floats in water) or dew retting (the hemp remains on the ground and is affected by the moisture in dew and by molds and bacterial action).

-

Industrial hempseed harvesting machine in France

-

Harvesting industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa) – This is a separate harvest for a different form of processing: The upper part of the plant with the leaves will be collected for cold pressing, while the lower part remains for producing fiber and initially it is left on the field.

-

Hemp being harvested

Pests

[edit]Several arthropods can cause damage or injury to hemp plants, but the most serious species are associated with the Insecta class. The most problematic for outdoor crops are the voracious stem-boring caterpillars, which include the European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis, and the Eurasian hemp borer, Grapholita delineana.[98] As the names imply, they target the stems reducing the structural integrity of the plant.[98] Another lepidopteran, the corn earworm, Helicoverpa zea, is known to damage flowering parts and can be challenging to control.[99] Other foliar pests, found in both indoor and outdoor crops, include the hemp russet mite, Aculops cannibicola, and cannabis aphid, Phorodon cannabis.[99] They cause injury by reducing plant vigor because they feed on the phloem of the plant. Root feeders can be difficult to detect and control because of their below surface habitat. A number of beetle grubs and chafers are known to cause damage to hemp roots, including the flea beetle and Japanese beetle, Popillia Japonica.[98] The rice root aphid, Rhopalosiphum rufiabdominale, has also been reported but primarily affects indoor growing facilities.[99] Integrated pest management strategies should be employed to manage these pests with prevention and early detection being the foundation of a resilient program. Cultural and physical controls should be employed in conjunction with biological pest controls, chemical applications should only be used as a last resort.

Diseases

[edit]Hemp plants can be vulnerable to various pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, nematodes, viruses and other miscellaneous pathogens. Such diseases often lead to reduced fiber quality, stunted growth, and death of the plant. These diseases rarely affect the yield of a hemp field, so hemp production is not traditionally dependent on the use of pesticides.

Environmental impact

[edit]Hemp is considered by a 1998 study in Environmental Economics to be environmentally friendly due to a decrease of land use and other environmental impacts, indicating a possible decrease of ecological footprint in a US context compared to typical benchmarks.[100] A 2010 study, however, that compared the production of paper specifically from hemp and eucalyptus concluded that "industrial hemp presents higher environmental impacts than eucalyptus paper"; however, the article also highlights that "there is scope for improving industrial hemp paper production".[101] Hemp is also claimed to require few pesticides and no herbicides, and it has been called a carbon negative raw material.[102][103] Results indicate that high yield of hemp may require high total nutrient levels (field plus fertilizer nutrients) similar to a high yielding wheat crop.[104] A United Nations report endorses the versatility and sustainability of hemp and its productive potential in developing countries. Hemp uses a quarter of the water required by cotton, and absorbs more carbon dioxide than other crops and most trees.[105]

Producers

[edit]The world-leading producer of hemp is China, which produces more than 70% of the world output. France ranks second with about a quarter of the world production. Smaller production occurs in the rest of Europe, Chile, and North Korea. Over 30 countries produce industrial hemp, including Australia, Austria, Canada, Chile, China, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, Germany, Greece,[106] Hungary, India, Italy, Japan, Korea, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, the United Kingdom and Ukraine.[107][108]

The United Kingdom and Germany resumed commercial production in the 1990s. British production is mostly used as bedding for horses; other uses are under development. Companies in Canada, the UK, the United States, and Germany, among many others, process hemp seed into a growing range of food products and cosmetics; many traditional growing countries continue to produce textile-grade fiber.

Air-dried stem yields in Ontario have from 1998 and onward ranged from 2.6 to 14.0 tons of dry, retted stalks per hectare (1–5.5 t/ac) at 12% moisture. Yields in Kent County, have averaged 8.75 t/ha (3.5 t/ac). Northern Ontario crops averaged 6.1 t/ha (2.5 t/ac) in 1998. Statistic for the European Union for 2008 to 2010 say that the average yield of hemp straw has varied between 6.3 and 7.3 ton per ha.[109][110] Only a part of that is bast fiber. Around one ton of bast fiber and 2–3 tons of core material can be decorticated from 3–4 tons of good-quality, dry-retted straw. For an annual yield of this level is it in Ontario recommended to add nitrogen (N):70–110 kg/ha, phosphate (P2O5): up to 80 kg/ha and potash (K2O): 40–90 kg/ha.[111] The average yield of dry hemp stalks in Europe was 6 ton/ha (2.4 ton/ac) in 2001 and 2002.[14]

FAO argue that an optimum yield of hemp fiber is more than 2 tons per ha, while average yields are around 650 kg/ha.[112]

Australia

[edit]In the Australian states of Tasmania, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, New South Wales, and most recently, South Australia, the state governments have issued licenses to grow hemp for industrial use. The first to initiate modern research into the potential of cannabis was the state of Tasmania, which pioneered the licensing of hemp during the early 1990s. The state of Victoria was an early adopter in 1998, and has reissued the regulation in 2008.[113]

Queensland has allowed industrial production under license since 2002,[114] where the issuance is controlled under the Drugs Misuse Act 1986.[115] Western Australia enabled the cultivation, harvest and processing of hemp under its Industrial Hemp Act 2004,[116] New South Wales now issues licenses[117] under a law, the Hemp Industry Regulations Act 2008 (No 58), that came into effect as of 6 November 2008.[118] Most recently, South Australia legalized industrial hemp under South Australia's Industrial Hemp Act 2017, which commenced on 12 November 2017.[119]

Canada

[edit]Commercial production (including cultivation) of industrial hemp has been permitted in Canada since 1998 under licenses and authorization issued by Health Canada.[120]

In the early 1990s, industrial hemp agriculture in North America began with the Hemp Awareness Committee at the University of Manitoba. The Committee worked with the provincial government to get research and development assistance and was able to obtain test plot permits from the Canadian government. Their efforts led to the legalization of industrial hemp (hemp with only minute amounts of tetrahydrocannabinol) in Canada and the first harvest in 1998.[121][122]

In 2017, the cultivated area for hemp in the Prairie provinces include Saskatchewan with more than 56,000 acres (23,000 ha), Alberta with 45,000 acres (18,000 ha), and Manitoba with 30,000 acres (12,000 ha).[123] Canadian hemp is cultivated mostly for its food value as hulled hemp seeds, hemp oils, and hemp protein powders, with only a small fraction devoted to production of hemp fiber used for construction and insulation.[123]

France

[edit]France is Europe's biggest producer (and the world's second largest producer) with 8,000 hectares (20,000 acres) cultivated.[124] 70–80% of the hemp fiber produced in 2003 was used for specialty pulp for cigarette papers and technical applications. About 15% was used in the automotive sector, and 5–6% was used for insulation mats. About 95% of hurds were used as animal bedding, while almost 5% was used in the building sector.[14] In 2010–2011, a total of 11,000 hectares (27,000 acres) was cultivated with hemp in the EU, a decline compared with previous year.[110][125]

-

Industrial hemp production in France

-

A hemp maze in France

Russia and Ukraine

[edit]

From the 1950s to the 1980s, the Soviet Union was the world's largest producer of hemp (3,000 square kilometres (1,200 sq mi) in 1970). The main production areas were in Ukraine,[126] the Kursk and Orel regions of Russia, and near the Polish border. Since its inception in 1931, the Hemp Breeding Department at the Institute of Bast Crops in Hlukhiv (Glukhov), Ukraine, has been one of the world's largest centers for developing new hemp varieties, focusing on improving fiber quality, per-hectare yields, and low THC content.[127]

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the commercial cultivation of hemp declined sharply. However, at least an estimated 2.5 million acres of hemp grow wild in the Russian Far East and the Black Sea regions.[128]

United Kingdom

[edit]In the United Kingdom, cultivation licenses are issued by the Home Office under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. When grown for nondrug purposes, hemp is referred to as industrial hemp, and a common product is fiber for use in a wide variety of products, as well as the seed for nutritional aspects and the oil. Feral hemp or ditch weed is usually a naturalized fiber or oilseed strain of Cannabis that has escaped from cultivation and is self-seeding.[129]

United States

[edit]In October 2019, hemp became legal to grow in 46 U.S. states under federal law. As of 2019, 47 states have enacted legislation to make hemp legal to grow at the state level, with several states implementing medical provisions regarding the growing of plants specifically for non-psychoactive CBD.[130]

The 2018 Farm Bill, which incorporated the Hemp Farming Act of 2018, removed hemp as a Schedule I drug and instead made it an agricultural commodity. This legalized hemp at the federal level, which made it easier for hemp farmers to get production licenses, acquire loans, and receive federal crop insurance.[131]

- NH 2014 N.H. Laws, Chap. 18, SD: HB 1008 (2020)

- S.D. Codified Laws Ann. §38-35-1 et seq.

- Authorizes the growth, production and transportation of hemp with a license, and directs the Department of Agriculture to submit a state plan to USDA.

- Requires a minimum of five contiguous outdoor acres for grower license applications, and requires any license applicants to submit to a state and federal criminal background investigation.

- Requires a transportation permit for any transporter traveling within or through the state and creates two types of industrial hemp transportation permits (grower licensee and general) provided by the Department of Public Safety.

- Creates the Hemp Regulatory Program Fund.[132]

The process to legalize hemp cultivation began in 2009, when Oregon began approving licenses for industrial hemp.[133] Then, in 2013, after the legalization of marijuana, several farmers in Colorado planted and harvested several acres of hemp, bringing in the first hemp crop in the United States in over half a century.[134] After that, the federal government created a Hemp Farming Pilot Program as a part of the Agricultural Act of 2014.[135] This program allowed institutions of higher education and state agricultural departments to begin growing hemp without the consent of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). Hemp production in Kentucky, formerly the United States' leading producer, resumed in 2014.[136] Hemp production in North Carolina resumed in 2017,[137] and in Washington State the same year.[138] By the end of 2017, at least 34 U.S. states had industrial hemp programs. In 2018, New York began taking strides in industrial hemp production, along with hemp research pilot programs at Cornell University, Binghamton University and SUNY Morrisville.[139]

As of 2017, the hemp industry estimated that annual sales of hemp products were around $820 million annually; hemp-derived CBD have been the major force driving this growth.[140]

Despite this progress, hemp businesses in the US have had difficulties expanding as they have faced challenges in traditional marketing and sales approaches. According to a case study done by Forbes, hemp businesses and startups have had difficulty marketing and selling non-psychoactive hemp products, as majority of online advertising platforms and financial institutions do not distinguish between hemp and marijuana.[141]

History

[edit]Gathered hemp fiber was used to make cloth long before agriculture, nine to fifty thousand years ago.[3] It may also be one of the earliest plants to have been cultivated.[143][144] An archeological site in the Oki Islands of Japan contained cannabis achenes from about 8000 BC, probably signifying use of the plant.[145] Hemp use archaeologically dates back to the Neolithic Age in China, with hemp fiber imprints found on Yangshao culture pottery dating from the 5th millennium BC.[142][146] The Chinese later used hemp to make clothes, shoes, ropes, and an early form of paper.[142] The classical Greek historian Herodotus (ca. 480 BC) reported that the inhabitants of Scythia would often inhale the vapors of hemp-seed smoke, both as ritual and for their own pleasurable recreation.[147]

Textile expert Elizabeth Wayland Barber summarizes the historical evidence that Cannabis sativa, "grew and was known in the Neolithic period all across the northern latitudes, from Europe (Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Romania, Ukraine) to East Asia (Tibet and China)," but, "textile use of Cannabis sativa does not surface for certain in the West until relatively late, namely the Iron Age."[148] "I strongly suspect, however, that what catapulted hemp to sudden fame and fortune as a cultigen and caused it to spread rapidly westwards in the first millennium B.C. was the spread of the habit of pot-smoking from somewhere in south-central Asia, where the drug-bearing variety of the plant originally occurred. The linguistic evidence strongly supports this theory, both as to time and direction of spread and as to cause."[149]

Jews living in Palestine in the 2nd century were familiar with the cultivation of hemp, as witnessed by a reference to it in the Mishna (Kil'ayim 2:5) as a variety of plant, along with arum, that sometimes takes as many as three years to grow from a seedling. In late medieval Holy Roman Empire (Germany) and Italy, hemp was employed in cooked dishes, as filling in pies and tortes, or boiled in a soup.[150] Hemp in later Europe was mainly cultivated for its fibers and was used for ropes on many ships, including those of Christopher Columbus. The use of hemp as a cloth was centered largely in the countryside, with higher quality textiles being available in the towns.

The Spaniards brought hemp to the Americas and cultivated it in Chile starting about 1545.[151] Similar attempts were made in Peru, Colombia, and Mexico, but only in Chile did the crop find success.[152] In July 1605, Samuel Champlain reported the use of grass and hemp clothing by the (Wampanoag) people of Cape Cod and the (Nauset) people of Plymouth Bay told him they harvested hemp in their region where it grew wild to a height of 4 to 5 ft. [153] In May 1607, "hempe" was among the crops Gabriel Archer observed being cultivated by the natives at the main Powhatan village, where Richmond, Virginia, is now situated;[154] and in 1613, Samuell Argall reported wild hemp "better than that in England" growing along the shores of the upper Potomac. As early as 1619, the first Virginia House of Burgesses passed an Act requiring all planters in Virginia to sow "both English and Indian" hemp on their plantations.[155] The Puritans are first known to have cultivated hemp in New England in 1645.[151]

United States

[edit]

George Washington pushed for the growth of hemp as it was a cash crop commonly used to make rope and fabric. In May 1765 he noted in his diary about the sowing of seeds each day until mid-April. Then he recounts the harvest in October which he grew 27 bushels that year.

It is sometimes supposed that an excerpt from Washington's diary, which reads "Began to seperate [sic] the Male from the Female hemp at Do.&—rather too late" is evidence that he was trying to grow female plants for the THC found in the flowers. However, the editorial remark accompanying the diary states that "This may arise from their [the male] being coarser, and the stalks larger"[156] In subsequent days, he describes soaking the hemp[157] (to make the fibers usable) and harvesting the seeds,[158] suggesting that he was growing hemp for industrial purposes, not recreational.

George Washington also imported the Indian hemp plant from Asia, which was used for fiber and, by some growers, for intoxicating resin production. In a 1796 letter to William Pearce who managed the plants for him, Washington says, "What was done with the Indian Hemp plant from last summer? It ought, all of it, to be sown again; that not only a stock of seed sufficient for my own purposes might have been raised, but to have disseminated seed to others; as it is more valuable than common hemp."[159][160]

Other presidents known to have farmed hemp for alternative purposes include Thomas Jefferson,[161] James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, Zachary Taylor, and Franklin Pierce.[162]

Historically, hemp production had made up a significant portion of antebellum Kentucky's economy. Before the American Civil War, many slaves worked on plantations producing hemp.[163]

In 1937, the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 was passed in the United States, levying a tax on anyone who dealt commercially in cannabis, hemp, or marijuana. The passing of the Act to destroy the U.S. hemp industry has been reputed to involve businessmen Andrew Mellon, Randolph Hearst and the Du Pont family.[164][165][166]

One claim is that Hearst believed[dubious – discuss] that his extensive timber holdings were threatened by the invention of the decorticator that he feared would allow hemp to become a cheap substitute for the paper pulp used for newspaper.[164][167] Historical research indicates this fear was unfounded because improvements of the decorticators in the 1930s – machines that separated the fibers from the hemp stem – could not make hemp fiber a cheaper substitute for fibers from other sources. Further, decorticators did not perform satisfactorily in commercial production.[168][164]

Another claim is that Mellon, Secretary of the Treasury and the wealthiest man in America at that time, had invested heavily in DuPont's new synthetic fiber, nylon, and believed[dubious – discuss] that the replacement of the traditional resource, hemp, was integral to the new product's success.[164][169][170][171][172][173][174][175] DuPont and many industrial historians dispute a link between nylon and hemp, nylon became immediately a scarce commodity.[clarification needed] Nylon had characteristics that could be used for toothbrushes (sold from 1938) and very thin nylon fiber could compete with silk and rayon in various textiles normally not produced from hemp fiber, such as very thin stockings for women.[168][176][177][178][179]

While the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 had just been signed into law, the United States Department of Agriculture lifted the tax on hemp cultivation during WWII.[180] Before WWII, the U.S. Navy used Jute and Manila Hemp from the Philippines and Indonesia for the cordage on their ships. During the war, Japan cut off those supply lines.[181] America was forced to turn inward and revitalize the cultivation of Hemp on U.S. soils.

Hemp was used extensively by the United States during World War II to make uniforms, canvas, and rope.[182] Much of the hemp used was cultivated in Kentucky and the Midwest. During World War II, the U.S. produced a short 1942 film, Hemp for Victory, promoting hemp as a necessary crop to win the war.[181] By the 1980s the film was largely forgotten, and the U.S. government even denied its existence.[183] The film, and the important historical role of hemp in U.S. agriculture and commerce was brought to light by hemp activist Jack Herer in the book The Emperor Wears No Clothes.

U.S. farmers participated in the campaign to increase U.S. hemp production to 36,000 acres in 1942.[184] This increase amounted to more than 20 times the production in 1941 before the war effort.[184]

In the United States, Executive Order 12919 (1994) identified hemp as a strategic national product that should be stockpiled.[185]

- History in the United States

-

Hemp for Victory, a short documentary produced by the United States Department of Agriculture during World War II

-

1942 United States Department of Agriculture War Board Letter of appreciation to Joe "Daddy Burt" Burton, a Kentucky hemp farmer for his support of the World War II Hemp for Victory campaign[186]

-

Joe "Daddy Burt" Burton, a recognized top Kentucky hemp farmer with harvested hemp, 1942. Photo by USDA War Board - Lexington, Kentucky.[187]

-

United States "Marihuana" production permit. During World War II farmers were encouraged to grow hemp for cordage, to replace Manila hemp previously obtained from Japanese-controlled areas. The U.S. government produced a film explaining the uses of hemp, called Hemp for Victory.

Historical cultivation

[edit]Hemp has been grown for millennia in Asia and the Middle East for its fiber. Commercial production of hemp in the West took off in the eighteenth century, but was grown in the sixteenth century in eastern England.[188] Because of colonial and naval expansion of the era, economies needed large quantities of hemp for rope and oakum. In the early 1940s, world production of hemp fiber ranged from 250,000 to 350,000 metric tons, Russia was the biggest producer.[168]

In Western Europe, the cultivation of hemp was not legally banned by the 1930s, but the commercial cultivation stopped by then, due to decreased demand compared to increasingly popular artificial fibers.[189] Speculation about the potential for commercial cultivation of hemp in large quantities has been criticized due to successful competition from other fibers for many products. The world production of hemp fiber fell from over 300,000 metric tons 1961 to about 75,000 metric tons in the early 1990s and has after that been stable at that level.[190]

Japan

[edit]

In Japan, hemp was historically used as paper and a fiber crop. There is archaeological evidence cannabis was used for clothing and the seeds were eaten in Japan back to the Jōmon period (10,000 to 300 BC). Many Kimono designs portray hemp, or asa (Japanese: 麻), as a beautiful plant. In 1948, marijuana was restricted as a narcotic drug. The ban on marijuana imposed by the United States authorities was alien to Japanese culture, as the drug had never been widely used in Japan before. Though these laws against marijuana are some of the world's strictest, allowing five years imprisonment for possession of the drug, they exempt hemp growers, whose crop is used to make robes for Buddhist monks and loincloths for Sumo wrestlers. Because marijuana use in Japan has doubled in the past decade, these exemptions have recently been called into question.[191]

Portugal

[edit]The cultivation of hemp in Portuguese lands began around the fourteenth century.[citation needed] The raw material was used for the preparation of rope and plugs for the Portuguese ships. Portugal also utilized its colonies to support its hemp supply, including in certain parts of Brazil.[192]

In order to recover the ailing Portuguese naval fleet after the Restoration of Independence in 1640, King John IV put a renewed emphasis on the growing of hemp. He ordered the creation of the Royal Linen and Hemp Factory in the town of Torre de Moncorvo to increase production and support the effort.[193]

In 1971, the cultivation of hemp became illegal, and the production was substantially reduced. Because of EU regulations 1308–70, 619/71 and 1164–89, this law was revoked (for some certified seed varieties).[194]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Britt Erickson (4 November 2019). "USDA releases hemp production requirements". C&EN Global Enterprise. 97 (43): 17. doi:10.1021/cen-09743-polcon4. ISSN 2474-7408. S2CID 213055550.

- ^ Robert Deitch (2003). Hemp: American History Revisited: The Plant with a Divided History. Algora Publishing. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-87586-226-2.

- ^ a b Tourangeau W (2015), "Re-defining Environmental Harms: Green Criminology and the State of Canada's Hemp Industry", Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 57 (4): 528–554, doi:10.3138/cjccj.2014.E11, S2CID 143126182

- ^ a b Keller NM (2013), "The Legalization of Industrial Hemp and What it Could Mean for Indiana's Biofuel Industry" (PDF), Indiana International & Comparative Law Review, 23 (3): 555, doi:10.18060/17887, archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2022, retrieved 18 May 2016

- ^ Johnson R (22 March 2019). Defining Hemp: A Fact Sheet (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Toth JA, Stack GM, Cala AR, Carlson CH, Wilk RL, Crawford JL, Viands DR, Philippe G, Smart CD, Rose JK, Smart LB (2020). "Development and validation of genetic markers for sex and cannabinoid chemotype in Cannabis sativa L." GCB Bioenergy. 12 (3): 213–222. Bibcode:2020GCBBi..12..213T. doi:10.1111/gcbb.12667. ISSN 1757-1707.

- ^ Swanson TE (2015), "Controlled Substances Chaos: The Department of Justice's New Policy Position on Marijuana and What It Means for Industrial Hemp Farming in North Dakota" (PDF), North Dakota Law Review, 90 (3): 602, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2016, retrieved 18 May 2016

- ^ Talbot G (2015). Specialty Oils and Fats in Food and Nutrition: Properties, Processing and Applications. Elsevier Science. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-78242-397-3.

- ^ Crime UN (2009). Recommended Methods for the Identification and Analysis of Cannabis and Cannabis Products: Manual for Use by National Drug Testing Laboratories. United Nations Publications. p. 12. ISBN 978-92-1-148242-3.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Mallory JP (1997), JP Mallory, DQ Adams (eds.), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (Illustrated ed.), London, UK: Taylor & Francis, p. 266, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5, archived from the original on 7 September 2024, retrieved 6 October 2020

- ^ Adams DQ (2006), JP Mallory, DQ Adams (eds.), The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, Oxford University Press, p. 166, ISBN 978-0-19-105812-7, archived from the original on 1 April 2024, retrieved 6 October 2020

- ^ a b c Barber E (1991), Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean, Princeton University Press, pp. 36–38, ISBN 978-0-691-00224-8, archived from the original on 1 April 2024, retrieved 6 October 2020

- ^ McConvell P, Smith M (2003), "Millers and Mullers: The archaeo-linguisitic stratigraphy of technological change in holocene Australia", in Henning Andersen (ed.), Language Contacts in Prehistory: Studies in Stratigraphy, John Benjamins Publishing, p. 181, ISBN 978-1-58811-379-5

- ^ a b c "Michael Karus: European Hemp Industry 2002 Cultivation, Processing and Product Lines". Journal of Industrial Hemp. 9 (2). London: Taylor & Francis. 2004.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Food and Nutrition Board, Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). "Chapter 4: Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". In Oria M, Harrison M, Stallings VA (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). pp. 120–121. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Retrieved 5 December 2024.

- ^ "America's First Hemp Drink - Chronic Ice - Making a Splash in the Natural Beverage Market". San Francisco Chronicle. Los Angeles. Vocus. 8 June 2011. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ a b c "USDA ERS - Industrial Hemp in the United States: Status and Market Potential" (PDF). Ers.usda.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ "Industrial fibre crops: business opportunities for farmers", gov.uk, Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, 13 June 2013, archived from the original on 8 March 2016, retrieved 18 May 2016

- ^ a b c "Nutrition Facts for Hemp Seeds (shelled) per 100 g serving". Conde Nast, Custom Analysis. 2014. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ a b Teterycz D, Sobota A, Przygodzka D, Łysakowska P (2021). "Hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) enriched pasta: Physicochemical properties and quality evaluation". PLOS ONE. 16 (3): e0248790. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1648790T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248790. PMC 7971538. PMID 33735229.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b Sun X, Sun Y, Li Y, Wu Q, Wang L (2021). "Identification and Characterization of the Seed Storage Proteins and Related Genes of Cannabis sativa L". Front Nutr. 8: 678421. doi:10.3389/fnut.2021.678421. PMC 8215128. PMID 34164425.

- ^ a b c d e f Farinon B, Molinari R, Costantini L, Merendino N (June 2020). "The seed of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): Nutritional Quality and Potential Functionality for Human Health and Nutrition". Nutrients. 12 (7): 1935. doi:10.3390/nu12071935. PMC 7400098. PMID 32610691.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b c d e Montero L, Ballesteros-Vivas D, Gonzalez-Barrios AF, Sánchez-Camargo AD (2022). "Hemp seeds: Nutritional value, associated bioactivities and the potential food applications in the Colombian context". Front Nutr. 9: 1039180. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.1039180. PMC 9875026. PMID 36712539.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b Yano H, Fu W (February 2023). "Hemp: A Sustainable Plant with High Industrial Value in Food Processing". Foods. 12 (3): 651. doi:10.3390/foods12030651. PMC 9913960. PMID 36766179.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b El-Sohaimy SA, Androsova NV, Toshev AD, El Enshasy HA (October 2022). "Nutritional Quality, Chemical, and Functional Characteristics of Hemp (Cannabis sativa ssp. sativa) Protein Isolate". Plants. 11 (21): 2825. doi:10.3390/plants11212825. PMC 9656340. PMID 36365277.

- ^ Burton RA, Andres M, Cole M, Cowley JM, Augustin MA (July 2022). "Industrial hemp seed: from the field to value-added food ingredients". J Cannabis Res. 4 (1): 45. doi:10.1186/s42238-022-00156-7. PMC 9338676. PMID 35906681.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b Callaway, J. C. (1 January 2004). "Hempseed as a nutritional resource: An overview" (PDF). Euphytica. 140 (1–2): 65–72. doi:10.1007/s10681-004-4811-6. S2CID 43988645. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ House JD, Neufeld J, Leson G (November 2010). "Evaluating the quality of protein from hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) products through the use of the protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score method". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 58 (22): 11801–7. Bibcode:2010JAFC...5811801H. doi:10.1021/jf102636b. PMID 20977230.

- ^ Rizzo G, Storz MA, Calapai G (September 2023). "The Role of Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) as a Functional Food in Vegetarian Nutrition". Foods. 12 (18): 3505. doi:10.3390/foods12183505. PMC 10528039. PMID 37761214.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b Seeds, hemp seed,hulled Archived 3 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine FoodData Central. USDA. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Ellison C, Moreno T, Catchpole O, Fenton T, Lagutin K, MacKenzie A, Mitchell K, Scott D (1 July 2021). "Extraction of hemp seed using near-critical CO2, propane and dimethyl ether". The Journal of Supercritical Fluids. 173: 105218. doi:10.1016/j.supflu.2021.105218. ISSN 0896-8446. S2CID 233822572. Archived from the original on 1 April 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Williams D (2020). Industrial Hemp as a Modern Commodity Crop. John Wiley & Sons. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-89118-632-8. Archived from the original on 1 April 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "CRRH, Archaeologists agree that cannabis was among the first crops cultivated by human beings at least over 6,000 years ago, and perhaps more than 12,000 years ago". Crrh.org. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2004. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Cronin ME (11 February 1995). "Hemp fashions are clean, comfy, and legal". The Free Lance-Star. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ "Going eco, going Dutch". Futuremakers.artez.nl. 17 July 2018. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ^ Carton G, Parigot J (2 June 2022). "Disappearing natural resources: what flowers tell us about new value chains". Journal of Business Strategy. 43 (4): 222–228. doi:10.1108/JBS-07-2020-0168. ISSN 0275-6668. Archived from the original on 29 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Carton G, Parigot J (2024). "Building Sustainable Value Chains From Hemp and Flowers". Stanford Social Innovation Review. doi:10.48558/GXDE-BA27. Archived from the original on 29 January 2024. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Novakiva P (2017). "Use of technical hemp in the construction industry" (PDF). MATEC Web of Conferences. 146: 1–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2021 – via The Institute of Technology and Businesses in Ceske Budejovice.

- ^ a b c "Renewable Hempcrete House: Energy Efficiency Monitoring Programme". www.nnfcc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "IRC Commentary Fundraiser | Hemp Building Institute". The HBI. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ "APPENDIX BL HEMP LIME HEMPCRETE CONSTRUCTION - 2024 INTERNATIONAL RESIDENTIAL CODE (IRC)". codes.iccsafe.org. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ "Hempcrete Approved for US Residential Building Codes — HempBuild Magazine". HempBuild Magazine. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ Campbell G (3 April 2012). David Griffiths and the Missionary "History of Madagascar". BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-20980-0.

- ^ a b "The Prospects of Hemp Building Materials | Environmental Professionals Network". 8 October 2014. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Hemp-lime construction panels on test at University's new Building Research Park". University of Bath. 30 June 2014. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "oldbuilders". www.oldbuilders.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d Stanwix W, Sparrow A (2014). The Hempcrete Book: Designing and Building with Hemp-Lime. Cambridge: Green Books.

- ^ a b c d Allin S (2012). Building with hemp. Seed Press.

- ^ Ceyte I (2008). État, acteurs privés et innovation dans le domaine des matériaux de construction écologiques: Le développement du béton de chanvre depuis 1986 (PDF) (Master's thesis). Institut d'Études Politiques de Lyon. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Konopný beton a izolace, hliněné omítky - Konopný beton". www.konopny-beton.cz. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "KONOPNÉ STAVBY". KONOPNÉ STAVBY (in Czech). Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Využití konopí ve stavebnictví". ASB Portal (in Czech). 22 March 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Hempcrete". Design Life-Cycle. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ isohemp (18 June 2018). "Are hemp blocks load-bearing?". IsoHemp - Sustainable building and renovating with hempcrete blocks. Retrieved 27 September 2024.

- ^ Seng B, Magniont C, Lorente S (1 July 2019). "Characterization of a precast hemp concrete block. Part II: Hygric properties". Journal of Building Engineering. 24: 100579. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2018.09.007. ISSN 2352-7102.

- ^ Mani S, Zorec P (18 July 2024), Hempcrete housing as a sustainable restoration solution at Novo Mesto, Slovenia: Building towards carbon neutrality performances, doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4615616/v1, retrieved 26 November 2024

- ^ "HempCrete – Beacon Pro360". Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ Koch W (13 September 2010). "Hemp homes are cutting edge of green building". usatoday. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "6 Advantages of Building With Hempcrete". 29 June 2017. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "About". KØL :: High Density Fibre Cement. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Hemp Concrete: A High Performance Material for Green-Building and Retrofitting. | urbanNext". 11 July 2017. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "NewspaperWood". Studio Mieke Meijer. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ "Thermoformable Composite Panels" (PDF). Composites World. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- ^ "Plastics". hemp.com. 14 May 2013. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ "Lotus announces hemp-based Eco Elise: a new type of 'green' car". transport20.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ "Green Cars, Fuel Efficiency and the Environment | Mercedes-Benz". Mbusa.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ "Michael Karus:European hemp industry 2001 till 2004: Cultivation, raw materials, products and trends, 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Paulapuro H (2000). "5". Paper and Board grades. Papermaking Science and Technology. Vol. 18. Finland: Fapet Oy. p. 114. ISBN 978-952-5216-18-9.

- ^ Van Roekel, Gerjan J. (1994). "Hemp Pulp and Paper Production". Journal of the International Hemp Association. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Van Roekel G Jr (1994). "Hemp Pulp and Paper Production". Journal of the International Hemp Association. 1: 12–14. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ "Hemp Harvest Management". Canadian Hemp Trade Alliance. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ "Hemp Fibre Production". Canadian Hemp Trade Alliance. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ a b c MALACHOWSKA EDYTA, PRZYBYSZ PIOTR, DUBOWIK MARCIN, KUCNER MARTA, BUZALA KAMILA (2015). "Comparison of papermaking potential of wood and hemp cellulose pulps". Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences; SGGW Forestry and Wood Technology (91): 134–137. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ a b Small E, Marcus D (2002). "Hemp: A New Crop with New Uses for North America". In J. Janick, A. Whipkey (eds.). Trends in New Crops and New Uses. ASHS Press. pp. 284–326. Archived from the original on 21 May 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Schubert, Pit. "Our ropes are much stronger than we believe". Union Internationale Des Associations D'Alpinisme. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- ^ NNFCC. In the US, pet manufacturers use hemp in dog and cat bedding. "Crop Factsheet: Hemp" Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, National Non-Food Crops Centre, 9 June 2008. Retrieved on 6 May 2009

- ^ "Phytoremediation: Using Plants to Clean Soil". Mhhe.com. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Hemp As Weed Control". gametec.com. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ Reisinger P, Lehoczky É, Komives T (1 March 2005). "Competitiveness and Precision Management of the Noxious Weed Cannabis sativa L. in Winter Wheat". Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis. 36 (4–6): 629–634. Bibcode:2005CSSPA..36..629R. doi:10.1081/CSS-200043303. ISSN 0010-3624. S2CID 96007971.

- ^ "COOLFUEL Episode: Sugarcane and Hempoline". Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ "Clean Energy Solutions". Hemp 4 Fuel. Archived from the original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Pollution: Petrol vs. Hemp". Hempcar.org. Archived from the original on 20 July 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Biofuels Facts". Hempcar.org. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Increased biogas production at the Henriksdals Waste Water plant, Cajsa Hellstedt et al., June 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ What Farmers Need to Know About Growing Hemp(https://www.agriculture.com) Archived 4 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine 22 July 2019.

- ^ Arnone V (24 July 2018). "Hemp vs Marijuana: The Important Differences Explained". Big Sky Botanicals. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ Adams C (17 November 2016). "The man behind the marijuana ban for all the wrong reasons". CBS News. Archived from the original on 24 December 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ a b This paper begins with a history of hemp use and then describes how hemp was constructed as a dangerous crop in the U.S. The paper then discusses the potential of hemp as an alternative crop. Luginbuhl, April M. (2001). "Industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L): The geography of a controversial plant". The California Geographer. Vol. 41. California Geographical Society. pp. 1–14. hdl:10211.2/2738.

Hemp contains less than 1% THC, or tetrahydrocannabinols, the psychoactive property in marijuana. In other words, smoking hemp cannot create a 'high.' ... The dense growth of hemp eliminates other weeds.... The best growing technique for hemp, planting 300 to 500 plants per square meter, also helps authorities easily tell the hemp from marijuana, which is a plant that is less densely cultivated. (Roulac 1997; 149).

- ^ a b Deitch R (2003). Hemp: American History Revisited: The Plant with a Divided History. Algora Publishing. pp. 4–26. ISBN 978-0-87586-226-2. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

Cannabis is ... a plant that played an important role in colonial America's prosperous economy and remained a valuable commercial commodity up until the Second World War.

- ^ ADAS (July 2005). "UK Flax and Hemp production: The impact of changes in support measures on the competitiveness and future potential of UK fibre production and industrial use" (PDF). Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Industrial Hemp Production and Management". Province of Manitoba: Manitoba Agriculture. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ a b Sawler J, Stout JM, Gardner KM, Hudson D, Vidmar J, Butler L, Page JE, Myles S (2015). "The Genetic Structure of Marijuana and Hemp". PLOS ONE. 10 (8): e0133292. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1033292S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133292. PMC 4550350. PMID 26308334.

- ^ Elsohly MA, Radwan MM, Gul W, Chandra S, Galal A (2017). Phytochemistry of Cannabis sativa L. Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products. Vol. 103. pp. 1–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-45541-9_1. ISBN 978-3-319-45539-6. PMID 28120229.