Polka

| Polka | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Early to mid-19th century, Kingdom of Bohemia, Austrian Empire |

| Derivative forms | |

| Regional scenes | |

| Other topics | |

Polka is a dance style and genre of dance music in 2

4 originating in nineteenth-century Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic. Though generally associated with Czech and Central European culture, polka is popular throughout Europe and the Americas.[1]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]

The term polka referring to the dance is believed to derive from the Czech words "půlka", meaning "half-step".

Czech cultural historian Čeněk Zíbrt attributes the term to the Czech word půlka (half), referring to both the half-tempo 2

4 and the half-jump step of the dance.[2]

This name has been changed to "Polka" as an expression of honour and sympathy for Poland and the Poles after the November Uprising 1830-1831. "Polka" meaning, in both the Czech and Polish languages, "Polish woman".[3] The name was widely introduced into the major European languages in the early 1840s.[3]

Origin and popularity

[edit]

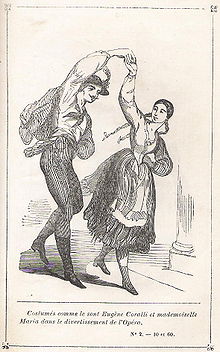

The polka's origin story first appears in the periodical Bohemia in 1844,[4] in which it was attributed to a young Bohemian woman named Anna Slezáková (born Anna Chadimová). As told by Čeněk Zíbrt, the music teacher Josef Neruda noticed her dancing in an unusual way to accompany a local folk song called "Strýček Nimra koupil šimla", or "Uncle Nimra Bought a White Horse" in 1830. The dance was further propagated by Neruda, who put the tune to paper and taught other young men to dance it.[2] Some versions of this origin story placed the first polka as being danced in Hradec Kralove, while others claimed it occurred in the village of Labska Tynica.[5] Historians believe the polka evolved as a quicker version of the waltz, and associate the rapid bourgeoning in popularity of the polka across Europe in the mid-1800s with the spread of the Romantic movement, which emphasized an idealized version of peasant culture.[6]

By 1835, this dance had spread to the ballrooms of Prague. From there, it spread to classical music hub Vienna by 1839,[7] and in 1840 was introduced in Paris by Johaan Raab, a Prague dance instructor.[4] It was so well received in Paris that its popularity was referred to as "polkamania."[8] The dance soon spread to London in 1844, where it was considered highly fashionable, and was also introduced to America.[4] It remained a popular ballroom dance in America, especially with growing Central, Northern, and Eastern European immigrant groups until the late 19th century.[9]

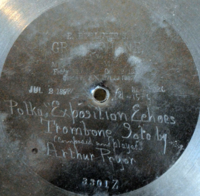

It may also be responsible for an increase in domestic popularity since the end of the 19th century, starting with the birth of recorded music, at first thanks to the many recordings provided by Emile Berliner's Gramophone company, which provided several examples of popular music. Some of the more desired American recordings include Berliner 230 ("Commodore Polka", played by W. Paris Chambers)[10] and the Berliner 3300s series (which include recordings like "The Signal polka" (BeA 3307) and "Exposition echoes polka" (BeA 3301), played by Arthur Pryor),[11][12] though most early records are extremely scarce or nonexistent anymore due to their fragile nature.

Styles and variants

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

There are various styles of contemporary polka besides the original Czech dance, which is still the chief dance at any formal or countryside ball in the Czech Republic.

Belarus

[edit]In the 1850s, polka was expanded among Belarusians, and was transformed by the national culture.[14][15] In different regions, local variants arose, which assimilated with local choreographic folklore and gained popularity. The ease of penetration of the polka into Belarusian choreography was due to its degree of proximity to Belarusian national choreographic traditions.[16]

The 2/4 meter polka merged well with Belarusian traditional dance, which had a similar meter. For example, "Trasucha" (Belarusian: "Трасуха", "Trasucha" or "Пацяруха", "Paciaruchais") a symbol of a typical folk dance, from which it received its name, and polka.[15] Most often in Belarus, the polka is performed in pairs, moving half a step with turns in a circle. The dance is decorated with a variety of small pas,[16] often accompanied by chastushkae.

Belarusian polkas are extremely rich in their choreographic and musical patterns, and are distinguished by great modal and intonation diversity.[15] Polka demands both skill and physical endurance from the dancers.

Like the square dance, the polka also has many local variants: "Віцебчанка, Viciebčanka", "Барысаўская, Barysaŭskaja", "Ганкоўская, Hankoŭskaja", and the names were also given according to the peculiarities of the choreography: "Through the leg", "With a podkindes", "With squats", "On the heel", "Screw" and others.[15]

United States

[edit]In the United States, polka is promoted by the International Polka Association based in Chicago, which works to preserve the cultural heritage of polka music and to honor its musicians through the Polka Hall of Fame. Chicago is associated with "Polish-style polka," and its sub-styles including "The Chicago Honky" (using clarinet and one trumpet) and "Chicago Push" featuring the accordion, Chemnitzer and Star concertinas, upright bass or bass guitar, drums, and (almost always) two trumpets.

Polka is popular in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where the "Beer Barrel Polka" is played during the seventh-inning stretch and halftime of Milwaukee Brewers and Milwaukee Bucks games.[17] Polka is also the official state dance of Wisconsin.[18]

The United States Polka Association is a non-profit organization based in Cleveland, Ohio.[19] Cleveland is associated with North American "Slovenian-style polka", which is fast and features piano accordion, chromatic accordion, and/or diatonic button box accordion. North American "Dutchmen-style" features an oom-pah sound often with a tuba and banjo, and has roots in the American Midwest.

"Conjunto-style" polkas have roots in northern Mexico and Texas, and are also called "Norteño". Traditional dances from this region reflect the influence of polka-dancing European immigrants from 1800s. In the 1980s and 1990s, several American bands began to combine polka with various rock styles (sometimes referred to as "punk polka"), "alternative polka".

Comedy musician "Weird Al" Yankovic is a fan of polka, and on every album since 1984 (with the exception of Even Worse), Al has taken bits of famous songs and modified them to fit polka style.

The Grammy Awards were first presented for polka in 1985. The first award went to Frankie Yankovic, known as "America's Polka King", for his 70 Years of Hits album on Cleveland International Records. Cleveland International Records had another polka Grammy winner with Brave Combo's Polkasonic in 1999. Other polka Grammy nominees included Frankie Yankovic's America's Favorites (1986), Songs of the Polka King Vol. I, Songs of the Polka King Vol. II (1997), and Brave Combo's Kick Ass Polkas (2000). Jimmy Sturr & His Orchestra is one of the most popular polka bands in America, having won 18 of the 24 awards for Grammy Award for Best Polka Album.

Polka Varieties was an hour-long television program of polka music originating from Cleveland, Ohio. The show, which aired in several U.S. cities, ran from 1956 until 1983. At that time, it was the only television program for this type of music in the United States.[20] A number of polka shows originated from the Buffalo Niagara Region in the 1960s, including WKBW-TV's Polka Time, which was hosted for its first half-year on air by Frankie Yankovic, and cross-border station CHCH-TV's Polka Party, hosted by Walter Ostanek.[21] In 2015, when Buffalo station WBBZ-TV launched the weekly Polka Buzz hosted by Ron Dombrowski, who also hosts the Drive Time Polkas radio show on WXRL Mondays-Saturdays from 5pm-7pm and on WECK Sundays from 8am-11am.[22])

Beginning with its inception in 2001, the RFD-TV Network aired The Big Joe Show, a television program that included polka music and dancing. It was filmed on location in various venues throughout the United States from 1973 through 2009. RFD-TV replaced The Big Joe Show with Mollie Busta's Polka Fest in January 2011; after Big Joe's death, reruns of The Big Joe Show returned to RFD-TV in 2015.[23]

In 2009, the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, which hosts the Grammy Awards, announced that it was eliminating the polka category[24] "to ensure the awards process remains representative of the current musical landscape".[24] A declining number of polka albums were considered for the award in previous years.[24]

South America

[edit]Peruvian polkas (becoming very popular in Lima). In the pampas of Argentina, the "polca" has a very fast beat with a 3

4 time signature. Instruments used are: acoustic guitar (usually six strings, but sometimes seven strings), electric or acoustic bass (sometimes fretless), accordion (sometimes piano accordion, sometimes button accordion), and sometimes some percussion is used. The lyrics always praise the gaucho warriors from the past or tell about the life of the gaucho campeiros (provincial gauchos who keep the common way). The polka was very popular in South and Southwest of Brazil, where it was mixed with other European and African styles to create the Choro. There also exist Curaçaoan polkas.

Ireland

[edit]The polka (polca in the Irish language) is also one of the most popular traditional folk dances in Ireland, particularly in Sliabh Luachra, a district that spans the borders of counties Kerry, Cork and Limerick.[25] Many of the figures of Irish set dances, which developed from Continental quadrilles, are danced to polkas. Introduced to Ireland in the late 19th century, there are today hundreds of Irish polka tunes, which are most frequently played on the fiddle or button accordion. The Irish polka is dance music form in 2

4, typically 32 bars in length and subdivided into four parts, each 8 bars in length and played AABB.[26][27][28][29] Irish polkas are typically played fast, at over 130 bpm, and are typically played with an off-beat accent.[30][31]

Nordic countries

[edit]The polka also migrated to the Nordic countries where it is known by a variety of names in Denmark (polka, reinlænderpolka, galop, hopsa, hamborger), Finland (polkka), Iceland, Norway (galopp, hamborgar, hopsa/hopsar, parisarpolka, polka, polkett, skotsk) and Sweden (polka). The beats are not as heavy as those from Central Europe and the dance steps and holds also have variations not found further south. The polka is considered a part of the gammeldans tradition of music and dance. While it is nowhere near as old as the older Nordic dance and music traditions, there are still hundreds of polka tunes in each of the Nordic countries. They are played by solo instrumentalists or by bands/ensembles, most frequently with lead instruments such as accordion, fiddle, diatonic accordion, hardingfele and nyckelharpa.

Polka in the classical repertoire

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

Bedřich Smetana incorporated the polka in his opera The Bartered Bride (Czech: Prodaná nevěsta) and in particular, Act 1.[32][33]

While the polka is Bohemian in origin, most dance music composers in Vienna (the capital of the vast Habsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was the cultural centre for music from all over the empire) composed polkas and included the dance in their repertoire at some point in their careers. The Strauss family in Vienna, for example, while better-known for their waltzes, also composed polkas that have survived. Joseph Lanner and other Viennese composers in the 19th century also wrote polkas to satisfy the demands of the dance-music-loving Viennese. In France, another dance-music composer, Émile Waldteufel, wrote polkas.

The polka evolved during the same period into different styles and tempos. In principle, the polka written in the 19th century has a four-theme structure; themes 1A and 1B as well as a 'Trio' section of a further two themes. The 'Trio' usually has an 'Intrada' to form a break between the two sections. The feminine and graceful 'French polka' (polka française) is slower in tempo and is more measured in its gaiety. Johann Strauss II's "Annen-Polka", Op. 114, "Demolirer-Polka, Op. 269, the "Im Krapfenwald'l", Op. 336, and the "Bitte schön!" polka, Op. 372, are examples of this type of polka. The polka-mazurka is also another variation of the polka, being in the tempo of a mazurka but danced in a similar manner as the polka. The final category of the polka form around that time is the Polka schnell, which is a fast polka or galop. Eduard Strauss is better known for this last category, as he penned the "Bahn Frei" polka, Op. 45, and other examples. Earlier, Johann Strauss I and Josef Lanner wrote polkas designated as a galop (quick tempo) or as a regular polka that may not fall into any of the categories above.

The polka was a further source of inspiration for the Strauss family in Vienna when Johann II and Josef Strauss wrote one for plucked string instruments (pizzicato) only, the "Pizzicato Polka".[34] Johann II later wrote the "Neue Pizzicato Polka" (New pizzicato-polka), Op. 449, culled from music of his operetta Fürstin Ninetta. Much earlier, he also wrote a "joke-polka" (German scherz-polka) entitled "Champagner-Polka", Op. 211, which evokes the uncorking of champagne bottles.

Other composers who wrote music in the style of the polka were Jaromír Weinberger, Dmitri Shostakovich and Igor Stravinsky.

See also

[edit]- List of polka artists

- Austrian folk dance

- Polkagris, a candy named after the dance

References

[edit]- ^ "The History of Polka: From Europe to Northeast Ohio". PBS Western Reserve. Retrieved 5 October 2024.

- ^ a b Čeněk Zíbrt, "Jak se kdy v Čechách tancovalo: dějiny tance v Čechách, na Moravě, ve Slezsku a na Slovensku z věků nejstarších až do nové doby se zvláštním zřetelem k dějinám tance vůbec", Prague, 1895 (Google eBook)

- ^ a b "polka, n.". Oxford University Press. (accessed 11 July 2012).

- ^ a b c Martin, Andrew R.; Ph.D, Matthew Mihalka (8 September 2020). Music around the World: A Global Encyclopedia [3 volumes]: A Global Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-499-5.

- ^ MARCH, RICK; Blau, Dick (2015). "Polka Heartland: Why the Midwest Loves to Polka". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 99 (1): 50–53. ISSN 0043-6534. JSTOR 26389332.

- ^ Gershon, Livia (10 February 2020). "The Rebellious, Scandalous Origins of Polka". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "History of polka". www.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ "Polkamania ... has raged very fiercely amongst us, indeed all over London this year." Letter by E. J. Knox,14 August 1844: quoted in A. E. Blake, Memoirs of a Vanished Generation ..., London (1909) viii, 217

- ^ March, Richard (1 June 2019). "American Polka in the Media: From Next to Nothing to 24/7". Transatlantica. Revue d'études américaines. American Studies Journal (1). doi:10.4000/transatlantica.14042. ISSN 1765-2766. S2CID 241758865.

- ^ "Berliner matrix 230. Commodore polka / Artists vary". Discography of American Historical Recordings. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Berliner matrix 3307. The signal polka / Arthur Pryor". Discography of American Historical Recordings. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ "Berliner matrix 3301. Exposition echoes / Arthur Pryor". Discography of American Historical Recordings. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- ^ Blatter, Alfred (2007). Revisiting Music Theory: A Guide to the Practice, p. 28. ISBN 0-415-97440-2.

- ^ Shavyrkin M. Belarusian polka // Zvyazda: gazeta. - 15 lutag 1997. - No. 32 (23133). — P. 8.

- ^ a b c d Churko, Yulia Mikhailovna (1994). Vyanok of Belarusian dances. Belarus. pp. 8, 88. OCLC 52282243.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Polka // Ethnagraphy of Belarus: Encyclopedia / Ed.: I. P. Shamyakin (gal. ed.) and insh. - Minsk: BelSE, 1989. - S. 406

- ^ "ESPN.com – Page2 – A great place ... for a tailgate". Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ "Wisconsin State Symbols". Wisconsin.gov. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006.

- ^ "United States Polka Association". United States Polka Association.

- ^ "Paul Wilcox, host of 'Polka Varieties' in Cleveland, dies at age of 85". Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ Forgotten Buffalo featuring Polonia Media. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Herr, Jim (14 April 2017). WBBZ-TV’s “Polka Buzz” hosts fun dance parties in Cheektowaga. Cheektowaga Chronicle. Retrieved 14 April 2017.

- ^ My Journey To Happiness (5 February 2011). "LIFE: observed: American Cultural Observation 331: RFD-TV's Polka Fest". Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Sisario, Ben (5 June 2009). "Polka Music Is Eliminated as Grammy Award Category". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann. "Comhaltas: Glossary". Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Alan Ng. "irishtune.info Rhythm Definitions – Irish Traditional Music Tune Index". Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Vallely, F. (1999). The Companion to Traditional Irish Music. New York University Press: New York, p. 301

- ^ "Irish Fiddle". Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ Lyth, D. Bowing. Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing. Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, p. 18.

- ^ Cooper, P. (1995). Mel Bay's Complete Irish Fiddle Player. Mel Bay Publications: Pacific, p. 19, 46

- ^ Cranitch, M. (1988). The Irish Fiddle Book. Music Sales Corporation: New York, p. 66.

- ^ "The Bartered Bride: Five fascinating facts". Opera North. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ "Smetana's Bartered Bride Gives a Taste of the Czech Countryside (in Boston)". WBUR-FM. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ John Palmer. Pizzicato Polka for orchestra, Op. 234 at AllMusic

Further reading

[edit]- Vaclovas Paukštė, Polka Lietuvoje ("Polka in Lithuania"), Vilnius, Vilnius Pedagogical University, 2000, 28 pages

External links

[edit]- National Cleveland-Style Polka Hall of Fame.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Polka Kings: Does Polka Music Really Come from Poland? from Culture.pl

- Donal Murphy & Matt Cronitch on YouTube, Sliabh Luachra polkas