Heated tobacco product

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A heated tobacco product (HTP)[note 1] is a tobacco product that heats the tobacco at a lower temperature than conventional cigarettes.[32] These products contain nicotine, which is a highly addictive chemical.[32] The heat generates an aerosol or smoke to be inhaled from the tobacco, which contains nicotine[33] and other chemicals.[17][32] HTPs may also contain additives not found in tobacco,[34] including flavoring chemicals.[32] HTPs generally heat tobacco to temperatures under 600 °C (1100 °F),[32][11][35] a lower temperature than conventional cigarettes.[36]

HTPs use embedded or external heat sources, heated sealed chambers,[37] or product-specific customized cigarettes.[32] Whereas e-cigarettes are electronic devices that vaporize a liquid containing nicotine, HTPs usually use tobacco in leaf or some other solid form, although there are some hybrid products that can use both solid tobacco and e-liquids.[37] There are various types of HTPs. The two most common designs are those that use an electric battery to heat tobacco leaf (e.g., IQOS, glo, Pax) and those that use a carbon ember that is lit and then heats the tobacco (e.g., Eclipse, REVO, TEEPS).[32] There are similar devices that heat cannabis instead of tobacco.[16][38]

A 2016 World Health Organization report did not find any evidence to support claims of lowered risk or health benefits compared to conventional cigarettes.[39] A 2018 Public Health England report includes evidence that indicates HTPs may be safer than traditional cigarettes, but less safe than e-cigarettes.[40] Some HTP aerosols studied were found to contain levels of nicotine and carcinogens comparable to conventional cigarettes.[3][41] Although heated tobacco products may be less dangerous than cigarette smoking, the UK Committee on Toxicity suggests that it would be better for smokers to completely stop.[41] There is insufficient evidence on the effectiveness of HTPs on quitting smoking,[36] or possible effects of second-hand exposure.[32] The limited evidence on air emissions from the use of HTPs indicates that toxic exposure from these products is greater than that of e-cigarettes.[42] Smokers have reported HTP use to be less satisfying than smoking a cigarette.[42]

As early as the 1960s, tobacco companies developed alternative tobacco products.[43] HTPs were introduced into the market in 1988, though they were not a commercial success.[35] The global decline in tobacco consumption may be one reason the industry has invented and marketed new products such as HTPs.[43] The latest generation of heated tobacco products may be an industry attempt to appeal with governments and health advocates by presenting a potential (but unproven) "harm reduction" product.[43] Current smoking bans may or may not apply to heated tobacco products.[44]

Health effects

[edit]

A 2016 Cochrane review found it unclear if the use of heated tobacco products (HTPs) would "substantially alter the risk of harm" over traditional cigarettes.[19] As of December 2017[update], it is impossible to quantify the health risk from using these products, as there is very limited information available on health effects.[41][23] It is unclear as to what the short- and long-term adverse effects are.[11][45] As of 2019[update], a limited number of independent studies have been conducted on HTPs, and further research will likely increase understanding of health effects.[46]

The different types of available HTPs vary in effect, creating a challenge for researchers.[47] It is unknown how users evaluate product safety—one study found that about half of people believed they are safer than traditional cigarettes.[48]

A 2016 World Health Organization report stated that claims of lowered risk or health benefits for HTPs compared with traditional cigarettes were based on industry-funded research, and compelling independent research was unavailable to support these claims. It also noted evidence that HTPs may be as dangerous as traditional cigarettes.[39] Action on Smoking and Health in the UK stated in 2016 that due to "the tobacco industry's long record of deceit" regarding the health risks involving smoking, it is important to conduct independent studies into the health effects of tobacco products.[49]

With an assorted range of electronic cigarettes devices available in the UK, it is unclear if HTPs offer any favorable benefit as a plausible harm reduction product.[40] A 2018 Public Health England report states that HTPs may be much safer than traditional cigarettes but less safe than e-cigarettes.[40] In a 2017 non-technical summary written by the Committee on Toxicity, it recommends that smokers completely stop, even though it found HTPs to be less harmful than smoking.[41]

Emissions

[edit]Heated tobacco products expose the user and bystanders to an aerosol.[50] The aerosol contains levels of nicotine, volatile organic compounds, and carcinogens comparable to regular cigarettes; they have also been found to contain more acenaphthene than regular cigarettes.[3][51] Other traditional cigarette emission substances such as tar, nicotine, carbonyl compounds (including acetaldehyde, acrolein, and formaldehyde), and nitrosamines are also found in HTPs.[10] A 2017 study found a 10% rise in carbon monoxide and formaldehyde air levels when HTPs were used indoors.[25] Another 2017 study discovered HTPs generated emissions of metal particulates, organic compounds, and aldehydes, and suggests that HTPs generate less concentrations of airborne contaminants in indoor places in comparison to a traditional cigarette,[25] though their use still reduces indoor air quality.[46]

A 2018 Public Health England report found that "[c]ompared with cigarettes, heated tobacco products are likely to expose users and bystanders to lower levels of particulate matter and harmful and potentially harmful compounds (HPHC). The extent of the reduction found varies between studies."[47] It also noted that the evidence indicates that less nicotine was inhaled from HTPs than cigarette smoke,[52] and exposure to mutagenic and other harmful substances is lower than with traditional cigarettes, though reduced exposure to harmful substances does not correlate with health risk severity.[11] Even low exposure can increase the risks for cancers, stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases compared to non-smokers.[11] Lower levels of harmful emissions have been shown, but lowering the risk to the smoker who transitions to using them has not been shown, as of 2018.[17] In 2017, the Committee on Toxicity found that HTPs do not reduce exposure or potential addiction to nicotine; some of the substances inhaled from using these products are carcinogens.[41]

Physiological changes in response to heated tobacco emissions, such as multiple organ system inflammation, energy metabolism, and carcinogenesis, have not been well characterised due to limited research in this area, especially in animal models.[36] A 2018 in vitro study suggested a less harmful pathophysiological response in human organotypic oral epithelial cultures when exposed to such emissions.[36] A 2016 animal study showed that heated tobacco emissions did not increase surfactant lipids and proteins, inflammatory eicosanoids and their metabolic enzymes, and several ceramide classes in HTP-exposed mice when compared with their counterparts that were exposed to cigarette smoke. It also discovered that even with reduced toxicants in HTP emissions, overuse (40 tobacco sticks per day) can still lead to eosinophilic pneumonia in humans.[36]

The impact on the overall population is unclear.[45] Studies on second-hand HTP emissions as of 2018 were diverse and largely affiliated with manufacturers.[7] There is disagreement over the extent to which HTPs generate air emissions, and the emissions' composition.[53] There is anticipated to be a reduced risk to bystanders where smokers were using heated tobacco products instead of smoking.[41] Limited evidence on air emissions suggests that toxic exposure from HTPs is greater than from e-cigarettes.[42] There is no safe level of exposure to harm carcinogens, making it difficult to assess how much HTPs reduce health risks.[54]

Addiction and quitting

[edit]HTPs contain the highly addictive chemical nicotine.[33] The nicotine content between HTP and traditional cigarette emissions are in similar ranges, which suggests a similar addictiveness and dependence potential.[11] There is insufficient evidence on the efficacy of heated tobacco products on quitting smoking.[36]

A 2018 World Health Organization report states that "[c]onclusions cannot yet be drawn about their ability to assist with quitting smoking (cessation), their potential to attract new youth tobacco users (gateway effect), or the interaction in dual use with other conventional tobacco products and e-cigarettes."[32] In 2017, the Ministry of Health in New Zealand stated that "[t]here is limited information on product use, including whether smokers are likely to switch completely from tobacco smoking or use both types of product, as well as initiation by non-smokers (including young people)."[55] In 2017, the Committee on Toxicity stated "[t]he Committees were concerned over the potential for non-smokers including children and young people, who would not otherwise start to smoke cigarettes, to take up using these products as they are not without risk."[56]

The availability of flavours in HTP products may appeal to non-smokers,[23] and evidence suggests that individuals who have never used tobacco products, especially children and adolescents, could be susceptible to new products that could lead to the use of traditional cigarettes.[3] In 2017, the Committee on Toxicity noted that "[c]ommittees were particularly concerned for young people, who do not smoke, starting to use these products, due to the potential for longer exposure over the remainder of their lives compared to adults and to possible differences in sensitivity."[56]

The dual use of HTPs and combustible products is common.[57] Trying an HTP was more frequent among adults below the age of 30 and regular traditional cigarette users.[58] A 2015 online survey found that 6.6% of 8240 respondents had tried an HTP at least once.[59] Research demonstrated that there is a high overlap between HTP users and female smokers.[48] According to four epidemiological papers, 10–45 per cent of non-smokers use these products, and show the effectiveness of the marketing of the tobacco industry[improper synthesis?]; for example, the HTP known as IQOS acts more as a gateway to traditional cigarette use (20% of users) than as a means of quitting (11% of users), and is not anticipated to have a lowered risk[clarification needed] among dual users who make up the remaining 69%.[17] In 2016 Philip Morris International (PMI) acknowledged that IQOS is probably as addictive as tobacco smoking.[49] IQOS is sold with a warning that states the best option is to avoid tobacco use altogether.[60]

IQOS can record the user's smoking habits. While Philip Morris International stated it only retrieves the data when the product is not working properly, Gregory Connolly, a professor at Northeastern University who has studied IQOS, said that tobacco companies like PMI would have a "mega database" of Americans' smoking habits, and possibly "reprogram the current puffing delivery pattern of the IQOS to one that may be more reinforcing and with a higher addiction potential".[61]

As of July 2017, not many US adults had tried using an HTP; approximately one in twenty US adults (including one in ten traditional cigarette users) have heard of HTPs.[58] In Italy, HTP use was 1.4% among the people and 3.1% among regular tobacco users.[clarification needed][48] A 2018 survey in Italy found that 45 per cent of people who experimented with the IQOS and 51 per cent who were interested in the product had never smoked before.[17] Therefore, such a product may represent, at least in Italy, a gateway for nicotine addiction among never-smokers rather than a harm reduction substitution for current smokers.[improper synthesis?][62]

In Germany, HTP use is not common and is generally more frequent among richer and educated smokers. Since its sale in Japan in 2014, HTP use has been high;[48] A 2017 survey in Japan found that of those who used the IQOS within the last month[when?], 20 per cent had never smoked before. The products did not satisfy 86 per cent of users, and they did not quit using traditional cigarettes; they used both.[17] HTP use among youth is unknown, but monitoring is underway as of March 2019[update].[63]

Nicotine yield

[edit]The limited data on HTP users show that they take short puffs and that the time between puffs is very short. Experimental tests show a higher volume of puffs at shorter intervals than with traditional cigarettes. A 2018 clinical trial found that tests of smokers switching to IQOS showed a tendency to take more puffs at shorter intervals.[17]

Users experience blood nicotine levels that peak after six to seven minutes for both HTPs and traditional cigarettes. The IQOS produces slightly less blood nicotine overall than a traditional cigarette, but more than nicotine gum. A 2016 study found that smokers were less satisfied and had a lower reduction in cravings with using an IQOS than with traditional cigarettes. In the study, smoking trial volunteers switching to an HTP, after an initial adjustment period, usually smoked more traditional cigarettes than those not switching, while reporting that they were less satisfying and rewarding than with regular cigarettes.[17]

Sharper peaks in blood nicotine levels from inhalation cause greater nicotine dependence than oral consumption. Nicotine replacement products, for instance, deliver nicotine in a slow, stable manner, which is less addictive. Inhaled nicotine enters the blood quicker than oral consumption, and blood nicotine levels halve every one to two hours. Nicotine withdrawal causes deteriorating mood and creates a craving for nicotine consumption.[64]

Pregnancy

[edit]Pregnant women who wish to quit smoking but are unable to are left with few options.[62] As nicotine replacement products are often ineffective for quitting smoking, pregnant women turn to alternatives such as HTPs.[36] There is no information available on the potential impact of HTP emissions from mother to fetus as of 2018[update].[36] The risk to the fetus from HTPs during pregnancy is hard to quantify [citation needed]; although the risk to the fetus is probably less than traditional smoking during pregnancy, the Committee on Toxicity recommends that expectant mothers completely stop smoking.[41] Nicotine is harmful to the infant and the growing adolescent brain,[3] is metabolised much faster while a woman is pregnant, easily passes through the placental barrier, and collects in breast milk. There is also growing evidence that nicotine exposure during pregnancy is linked to early birth, stillbirth, and abnormal brain growth.[64] Nicotine may result in adverse effects to the neurological growth of the fetus.[65]

Nicotine can lead to vasoconstriction of uteroplacental vessels, which reduces the delivery of both nutrients and oxygen to the fetus. As a result, nutrition is re-distributed to prioritize vital organs, such as the heart and the brain, at the cost of less vital organs, such as the liver, kidneys, adrenal glands, and pancreas, which can lead to underdevelopment and functional disorders later in life. Animal research in regards to maternal nicotine exposure on rats showed a direct adverse impact on pancreas development by reducing endocrine pancreatic islet size and number, which was accompanied by a decrease in gene expression of specific transcription factors and blood glucose regulating hormones such as insulin and glucagon. Affected rats exhibited significant pancreatic dysfunction and glucose intolerance. Other animal studies have reported insulin resistance in adult offspring due to maternal nicotine exposure; in animal models, nicotine has also been shown to activate nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the brain, which regulate brain development. Nicotine exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy (2 mg/kg/d) leads to structural changes in the hippocampus and somatosensory cortex in rats.[36]

Construction

[edit]

Nicotine is released from tobacco heated above 150 °C.[66] The burning process, substances emitted and their levels vary at different temperatures: distillation—the process during which nicotine and aromas are transferred from tobacco to smoke—occurs below 300 °C; pyrolysis occurs around 300 °C–700 °C and involves the decomposition of biopolymers, proteins, and other organic materials and generates the majority of substances emitted in smoke; and combustion occurs above 750 °C and results in the generation of carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and water.[18]

The temperature the tobacco reaches greatly varies among HTPs; it depends on the process used to heat the tobacco.[41] For example, HeatSticks are heated to a maximum of 350 °C, a temperature sufficient to enable pyrolytic decomposition of some organic materials,[18] while the glo iFuse heats tobacco to around 35 °C.[17] The formation of toxic volatile organic compounds, including formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acrolein, have been reported in e-cigarette aerosols at similar temperatures as the IQOS; flavoring chemicals in e-cigarettes have been discovered to undergo thermal degradation and contribute significantly to levels of toxic aldehydes emitted in e-cigarette aerosols,[relevant?][18] as demonstrated by the presence of carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides, soot or tars, and aldehydes in emissions.[17] Gases, liquid, and solid particles are also found in the emissions; the solids in the emissions have been called nicotine-free dry particulate matter rather than tar in papers written by people connected to the tobacco industry.[17]

Since the constituents of HeatSticks may differ from combustible cigarettes, including flavourants and additives, it is plausible that the IQOS aerosol may contain substances not found in tobacco smoke.[18] The emissions of the IQOS HeatSticks and the IQOS menthol mini-cigarettes contain about three times the amount of water and about half the amount of tar found in traditional cigarette emissions.[17] The IQOS HeatSticks do not generate a flame, but are charred after use.[67] Until 2016, Phillip Morris International researchers stated their IQOS product produces smoke.[17]

The HTP consists of three components with different functions: the processed tobacco stick; a pen-like heater (holder) that the tobacco stick is inserted, which is then heated by an electrically controlled heating element; and a charger that recharges the heater after use.[11] The heated tobacco products automatically stops the heating process after six minutes or 14 moves(puffs)[clarification needed] so that pyrolytic products and pollutant release are limited in time as well as by a maximum number of puffs per stick.[11] HTPs may not generate side-stream smoke because they do not fully combust, but the temperatures reached are sufficient for pyrolysis to happen.[10]

There are devices that use a reaction that resembles pyrolysis or combustion, but research has not determined which of the two it is.[17] The tobacco stick contains a compressed tobacco film made of a dried tobacco suspension that has been rolled up into a paper-thin brown tobacco foil and several filter elements.[11] This film consists of about 70% tobacco, as well as humectants (such as water and glycerin, to prevent the tobacco from drying out and promote aerosol formation), binders, and flavorings. The filter elements consist of two independent systems: a polymer film filter that cools the aerosol, and a soft cellulose acetate mouthpiece filter that mimics the sensory aspects of a traditional cigarette.[11]

HTPs are battery-powered systems that produce nicotine-containing emissions by heating tobacco.[11] For this purpose, tobacco sticks are placed in a corresponding heater and heated to about 250–350 °C (around 500 °F),[11][35] which result in nicotine-containing emissions that are inhaled via a mouthpiece with a filter segment.[11] HTPs are hybrids between electronic and conventional cigarettes: they are equipped with a device that heats the product without reaching combustion to generate aerosol, while using "real" tobacco instead of nicotine-containing liquids.[62] There are products that have a time limit so that the user is forced to inhale the nicotine within 3.5–10 minutes prior to the device turning off.[17] This function helps support blood nicotine peaks that result in an increased nicotine dependence.[17]

There are three general types of heated tobacco products.[41] One that immediately heats processed tobacco to generate aerosol, another that uses processed tobacco that is heated in (but not generate) an aerosol, and one where the processed tobacco gives flavour to the aerosol as the latter moves over the former.[41] HTPs heat tobacco leaves at a lower temperature than traditional cigarettes.[36] Another type of HTP is the loose-leaf tobacco vaporizer that involves putting loose-leaf tobacco into a chamber that is electrically heated with an element.[29]

History

[edit]As early as the 1960s, the tobacco companies developed alternative tobacco products to supplement the cigarette market.[43] The first commercial HTP was the Premier by R. J. Reynolds,[68] a smokeless cigarette launched in 1988 and described as difficult to use.[26] Many smokers disliked the taste,[69] and it was not popular with users when it was test-marketed in Arizona and Missouri.[70] It was shaped like a traditional cigarette, and required combustion to move the smoldered charcoal past processed tobacco containing more than 50 percent glycerin to create an aerosol.[71][72] In 1989,[73] after spending $325 million,[74] R. J. Reynolds pulled the Premier from the market after the American Medical Association and other organizations recommended that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) restrict it or classify it as a drug.[75]

The Premier product concept was developed further and re-launched as the Eclipse in the mid-1990s,[73][76] which was available in limited distribution as of 2015[update],[77] and promoted via viral marketing.[73] Reynolds American also introduced a brand called Revo and stated that it was a "repositioning" of the Eclipse.[78] The Revo was withdrawn in 2015.[77]

The Steam Hot One was sold in Japan by Japan Tobacco.[79]

In October 1998, Philip Morris launched the Accord in the US. It was a specialised cigarette was designed to be used with the electric heating system. Advertisements stating reduced risk were drafted for the Accord in the US, but were never released.[20] In 1998, the company launched the Accord in Osaka, Japan, and renamed it Oasis. The battery-powered, pager-size product was marketed as "low-smoke".[20][80] An attempt was made in 2007 by Kenneth Podraza, the Vice President of Research and Development at Philip Morris in the US at the time, to get the Surgeon General of the United States to endorse it.[20] The Surgeon General did not reply to Podraza's letter.[20] Few people used the Accord, and most of them also continued to use traditional cigarettes.[20] The Accord ceased production in 2006.[20]

In 2007 Philip Morris International launched the Heatbar,[81] which was very similar to the Accord.[20] It was around the size of a mobile phone and was said to heat specially-designed cigarettes rather than burning them.[82] The Heatbar did not obtain any significant user reception,[83] and was discontinued after the only benefit found was to lower second-hand smoke.[84] The Accord and Heatbar are predecessors of Philip Morris International's current HTPs.[85] HTPs were not a commercial success, and most of them were quickly taken off the market following their debut.[relevant?][35]

In years leading up to 2018, increased tobacco control measures have directed the tobacco industry to develop alternative tobacco products, such as HTPs.[11] There has been a global decline in tobacco consumption that, if continued, will negatively impact the tobacco industry's profits, which has forced the industry to invent and market new products like HTPs.[43] The introduction of HTPs may also have been a response to the growing popularity of e-cigarettes beginning around 2007 after independent companies introduced them before major multinational tobacco companies entered the e-cigarettes market.[43]

The global decline of cigarette consumption and decrease in adult smoking prevalence (from 24% in 2007 to 21% in 2015), combined with the success of tobacco control, including the implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, may also have led the tobacco companies to consider alternative products to protect their profits and political interests.[43] T.L. Caputi suggests that the ubiquity of e-cigarettes and the growing dissatisfaction with not providing a "throat-hit"[clarification needed] may present an opportunity for HTPs.[35] Philip Morris International anticipates a future without traditional cigarettes, but campaigners and industry analysts question the probability of traditional cigarettes being overshadowed by either e-cigarettes or other products like the IQOS.[86]

Products

[edit]

HTPs use a heating system where the tobacco is heated and aerosolised.[32] In addition to nicotine, they contain additives that are flavoured and derived from substances other than tobacco.[32] Evidence shows that the concentrations of nicotine in mainstream HTP aerosols are lower than in cigarette smoke.[52] Smokers regularly reported HTP use to be less satisfying than smoking a cigarette.[42] Tested HTPs provided more nicotine in the aerosol than a cigalike e-cigarette but not as much nicotine compared with a tank-style e-cigarette.[42][relevant?]

HTPs are designed to be similar to their combustible counterparts by replicating the oral inhalation and exhalation, taste, rapid systemic delivery of nicotine, hand-to-mouth feel and throat hit sensations (depending on the temperature) when smoking traditional cigarettes.[87][36] HTPs aim for a niche between combustible tobacco smoking and e-cigarettes that aerosolise nicotine.[7] There are different types of HTPs in the marketplace:[16] some use tobacco sticks like glo and IQOS, while others use loose-leaf tobacco such as Pax and Ploom.[32]

Firefly vaporizers

[edit]The Firefly developed the Firefly 2, which heats loose-leaf plant material and concentrates and is often used to aerosolise cannabis,[16] and is more compact than the original Firefly vaporizer.[88] It uses a patented heating technology that heats the device up to the desired temperature (between 200 and 500 °F) with each puff rather than a preset temperature setting from the beginning.[89]

glo

[edit]In 2016, British American Tobacco launched a battery-powered heated product called glo in Japan before selling it in South Korea,[90] Switzerland, Russia,[12] and Ukraine.[91] In France, glo uses tobacco sticks called Neostiks.[17] It uses a heating element with a tobacco stick that heats up to 240 °C.[87][17] glo produces approximately 50% less nicotine emissions than IQOS.[46] In May 2017 British American Tobacco released i-glo in Canada.[92] Bonnie Herzog, a senior analyst at Wells Fargo Securities, stated that the proposed acquisition of R. J. Reynolds by British American Tobacco in 2016 would let them catch up with the competition.[93] glo is marketed as being easier to operate than IQOS.[91]

The glo iFuse debuted in Romania in 2015,[87] and is a hybrid of a heated tobacco product and an e-cigarette.[18] It consists of a heating element, a liquid tank (like e-cigarettes), and a tobacco cavity through which the aerosol passes and is infused with tobacco flavour.[18] It uses cartridges called Neopods, and heats tobacco to approximately 35 °C.[17]

IQOS

[edit]

IQOS (/ˈaɪkoʊs/ EYE-kohs) is a non-combustible "reduced risk" smoking alternative that was introduced in June 2014 and is marketed by Philip Morris International (PMI) under the Marlboro and Parliament brands.[94][95] Although it is marketed as a novel product, it is very similar to the Accord released by the same company in 1998; however, the IQOS sticks have more nicotine, more tar, and less tobacco.[20] They are heated at a lower temperature.[20]

Initially launched in 2014 in Nagoya, Japan, and Milan, Italy, IQOS is being introduced to other countries;[96] As of October 2019[update], it is available in 49 countries.[97] PMI has projected that when 30 billions units are sold, the IQOS would increase profits by $700 million.[98] In October 2018, PMI introduced a less expensive version of IQOS called IQOS 3 in Tokyo, Japan.[99] The IQOS 3 Multi was also launched, and is capable of multiple consecutive uses.[100]

The IQOS consists of a charger around the size of a mobile phone and a pen-like holder.[101] The disposable tobacco stick, also known as a HeatStick,[102][103] is described as a mini-cigarette.[17] The sticks contain processed tobacco soaked in propylene glycol.[102] The stick is inserted into the holder which then heats it to temperatures up to 350 °C,[104] and the amount of nicotine provided may be a little strong for light cigarette smokers.[105] Users have reported less smell and odor on clothing.[72] There is a limited amount of research on the effect of IQOS on the user's health.[106]

The physical effects on users are not yet known.[107] The emissions of IQOS are considered to be smoke by independent researchers, and were called smoke by Phillip Morris researchers until 2016.[108] The emissions generated by IQOS contain the identical harmful constituents as tobacco cigarette smoke, including volatile organic compounds at comparable levels to cigarette smoke, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and carbon monoxide.[3] Each of these substances, on the basis of rigorous research of cigarette smoke, are known to result in significant harms to health.[3] According to Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, IQOS is "harmful to health, but probably less harmful than smoking tobacco cigarettes".[109]

In 2016, PMI submitted a multi-million page application to the US FDA for IQOS to be authorized as a modified risk tobacco product.[110] In March 2017, PMI submitted a premarket tobacco product application regarding its IQOS product to the US FDA.[111] In December 2017, Reuters published documents and testimonies of former employees detailing irregularities in the clinical trials conducted by PMI for the approval of the IQOS product by the US FDA.[112] The advisory panel appointed by the US FDA reviewed Philip Morris International's application in January 2018.[113] The FDA granted permission to PMI to sell IQOS in the US on 30 April 2019, which also requires the company to follow strict marketing restrictions.[114] IQOS formally launched in the US in October 2019.[97] On 7 July 2020, the US FDA announced its ruling 456, which granted an "exposure modification" order that allows PMI to market IQOS in the United States.

iSmoke OneHitter

[edit]The iSmoke OneHitter by iSmoke can be used as a loose-leaf tobacco vaporizer or for use with waxy oils.[115] It is described as a "heat, not burn" tobacco vaporizer,[116] and was launched in 2015.[117] It has a chamber that can be filled with up to 800 milligrams of tobacco.[115]

IUOC 2

[edit]The IUOC 2 is marketed by Shenzhen Yukan Technology Co., Limited, of China.[118] The HTP can use any pack of 20 cigarettes on a single battery charge and does not use tobacco-filled cartridges.[118] It is an updated version over the original IUOC and was formally launched in 2018 at InterTabac in Germany.[118]

lil

[edit]The lil is an HTP that heats a cigarette stick with a circular blade that was launched by the Korea Tobacco & Ginseng Corporation on 20 November 2017.[119][120] According to the company, a two-hour battery charge lasts for up to 20 cigarette sticks, its refills are cheaper than the IQOS and glo, and will fit in the IQOS product, though they do not recommend doing so for safety reasons.[119]

Mok

[edit]In May 2019, China Tobacco debuted the Mok in Korea.[121] According to the company, Mok is more compact and weighs less than other products such as glo, IQOS, and lil.[121] The Coo[clarification needed] sticks are longer and wider than tobacco sticks from other companies.[121]

Pax vaporizers

[edit]In 2010, the company Ploom (later rebranded as Pax Labs) launched a butane-powered product used to heat tobacco or botanical products.[122] Later models replaced the butane heating with an electric system.[123] The Pax 2 vaporizer uses loose plant material such as tobacco or cannabis and remains cool to the touch while the oven heats to one of four temperatures (up to 455 °F).[124][125] The Pax 3 takes 15 seconds to heat up and can be used to heat cannabis flowers.[126]

Ploom vaporizers

[edit]In January 2016, Japan Tobacco released Ploom,[127] which has been withdrawn from the US.[87] The brand remained with Japan Tobacco and the product has been replaced with Ploom Tech, where an aerosol passes through a capsule of granulated tobacco leaves.[128] The Ploom brand uses aluminum capsules called Vapodes, where tobacco can heat up to 180 °C.[17] Because the Ploom Tech heats up more, it may generate more harmful emissions.[17] In January 2019, Japan Tobacco introduced Ploom TECH+ and Ploom S in Tokyo, Japan.[129]

Sales expanded throughout Japan in 2017.[130] Japan Tobacco intended to spend $500 million to increase their heated tobacco manufacturing capacity by late 2018.[131] Studies have not been conducted on Japan Tobacco International's Ploom product as of 2017[update].[55]

Pulze

[edit]In 2018, Imperial Brands was developing a heated tobacco product named Pulze.[132]

TEEPS

[edit]In December 2017, PMI launched TEEPS in the Dominican Republic.[133] It is an HTP that looks similar to a traditional cigarette.[133] Instead of an electrically controlled heating system, it uses a carbon heat source that, once lit, passes heat to a processed tobacco plug.[134]

Cigoo

[edit]In September 2020, Yunnan Xike Science & Technology Co., Ltd. launched Cigoo;[135] according to the company, it is a heated herbal product which releases nicotine and aroma aerosol at 300 °C, similar to mainstream HTPs.[135] Instead of using reconstituted tobacco film in the stick,[11] Cigoo sticks use patented plant particle as a carrier, added flavourants and additives.[136]

TEO

[edit]The TEO heats a cigarette stick with a heating blade, and was launched by Shenzhen ESON Technology Co. Ltd. ("ESON") in Dec. 2021 after PODA. NEAFS tobacco-free sticks does not use tobacco, but instead a nicotine infused, tea-based organic compound.[137]

Comparison to mainstream smoke of traditional cigarettes

[edit]Contents of selected analytes in the mainstream aerosol of a heated tobacco product compared to the mainstream smoke of traditional cigarettes.[11] The highest and lowest values in two different types of tobacco sticks and traditional cigarettes were given by Mallock et al. and Counts et al. respectively.[11] Column 5 shows the reduction of the analytes in the mainstream aerosol of the heated tobacco product compared to traditional cigarettes by percentage.[11]

| Tobacco sticks (Mallock et al. 2018; [15]) | Traditional Cigarettes (Counts et al. 2005; [18]) | Reduction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Unit | Min.–Max. | Min.–Max. | % |

| Puff count | puff/stick | 12 | 5.5–13.6 | – |

| TPM | mg/stick | 51.2–52.6 | 27.5–60.9 | – |

| Nicotine | mg/stick | 1.1 | 1.07–2.70 | – |

| Water | mg/stick | 28.0–31.7 | 9.8–21.4 | – |

| NFDPM | mg/stick | 19.8–21.6 | 16.3–37.6 | – |

| Acetaldehyde | μg/stick | 179.4–183.5 | 930–1540 | 80.5–88.2 |

| Acrolein | μg/stick | 8.9–9.9 | 89.2–154.1 | 89.5–93.9 |

| Formaldehyde | μg/stick | 4.7–5.3 | 29.3–130.3 | 82.9–96.2 |

| Crotonaldehyde | μg/stick | <3.0 | 32.7–70.8 | – |

| 1.3-Butadiene | μg/stick | 0.20–0.2 | 77.0–116.7 | 99.7–99.8 |

| Benzine | μg/stick | 0.5–0.6 | 49.7–98.3 | 98.8–99.4 |

| Isoprene | μg/stick | 1.8–2.1 | 509–1160 | 99.6–99.8 |

| Styrene | μg/stick | 0.5 | 15.4–33.3 | 96.9–98.6 |

| Toluene | μg/stick | 2.0–2.2 | 86.2–176.2 | 97.6–98.8 |

Tobacco stick, i.e. for heated tobacco products: a tobacco stick; for traditional cigarette: a cigarette.[11]

All values were generated using the Health Canada Intense (HCI) puffing conditions.[11]

TPM = total particulate matter, and NFDPM = nicotine-free dried particulate matter.[11]

Prevalence

[edit]

As of 2017[update], HTPs are being introduced in markets around the world,[138] and since October 2019, they have been sold in at least 49 countries.[97] They are not as globally popular as the e-cigarette, which has an estimated global user count of 20 million.[36][139] As of 2018[update], the IQOS is the most popular product,[36] and was authorised for marketing by the FDA in the US on 30 April 2019.[114]

As of January 2018[update], the industry has been rapidly introducing new heated tobacco products.[43] HTPs were first sold in Japan,[140] and several brands have been marketed there since 2014.[138] Since the introduction of HTP in Japan there has been a 32% drop in the sale of tobacco cigarettes.[141]

The share of the market in South Korea for heated tobacco products has surged at least five-fold during the last two years leading up to 2019.[142] As of early 2018, these products are not sold in France.[17]

Tobacco industry leaders predicted that HTPs may displace traditional cigarette smoking and, by extension, tobacco control strategies typically framed around cigarettes.[138]

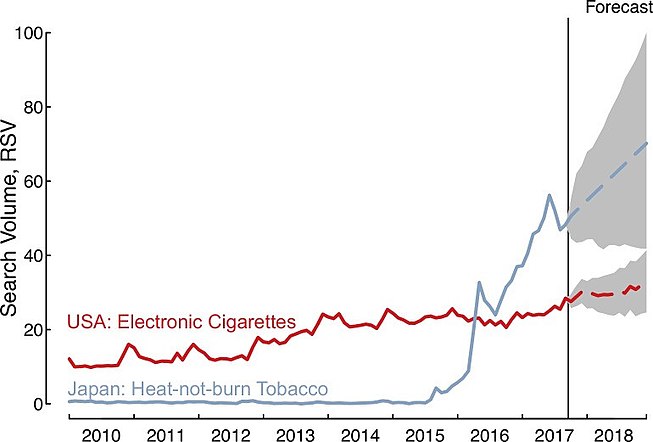

Since the introduction of PMI's IQOS brand in select Japanese cities in November 2014, web searches in Japan for "heat-not-burn products" (a marketing name for HTPs) increased substantially; average monthly searches rose 1,426% (95% CI: 746–3,574) during 2015–2016, and they continued to grow an additional 100% (95% CI: 60–173) between 2016 and 2017; in practical terms, there are now between 5.9 and 7.5 million heat-not-burn related Google searches in Japan each month based on the latest search estimates for September 2017. Moreover, forecasts relying on the historical trend suggest heat-not-burn searches would increase an additional 32% (95%CI: -4 to 79) during 2018, compared to current estimates for 2017 (January–September), with further growth expected.[138][needs update]

Queries for heat-not-burn in Japan occur more frequently than queries for e-cigarettes in the United States, with the Japanese heat-not-burn queries first eclipsing e-cigarette queries in April 2016.[138] Further, the change in average monthly queries for heat-not-burn in Japan between 2015 and 2017 was 399 (95% CI: 184–1,490) times larger than the change in average monthly queries for e-cigarettes in the United States over the same time period, increasing by 2,956% (95% CI: 1,729–7,304) compared to only 7% (95% CI: 3–13), which indicate that interest in heat-not-burn may outpace interest in e-cigarettes in the future.[138]

-

Google searches for heat-not-burn tobacco (heated tobacco) outpace rise of electronic cigarettes.[138] The above figure shows the Relative Search Volume (scaled from 0–100 and adjusted for number of total Google search volumes per month in Japan and the USA) for heat-not-burn and e-cigarette products.[138]

HTP demand presents a host of tobacco control challenges similar to e-cigarettes and new challenges specific to these products. They have been advertised as reduced-risk tobacco products in their Japanese test market.[138]

Marketing

[edit]

The term "heat-not-burn" refers to tobacco heated (at ~350 °C) by an electrically powered element or carbon instead of being fully combusted (at ~800 °C).[36] Terms used in marketing for cigarette-like products that "heat rather than burn" refer to them as "reduced risk" and "innovative".[16] Marketing slogans like "heat-not-burn" cannot be a substitute for science.[102][opinion] The tobacco industry has described them as "not-burned" (heat-not-burn), though it has backtracked from this claim as of 2018[update].[17] HTPs are not typically marketed as a harmless substitute to smoking,[48] though they have been marketed as a "smoke-free" alternative to traditional cigarettes, and promoted as a way to lower risk from smoking.[28] The IQOS product has been advertised as emitting "no smoke".[143] This advertisement claim is not a replacement for science.[3][opinion] It is expected that the promotion associated with these products will worsen the worldwide tobacco risk.[17]

Companies employ similar strategies previously used for traditional cigarettes, such as marketing through a variety of outlets, including celebrity endorsements.[144] "The tobacco industry has opened heated tobacco product flagship stores, cafes and sponsored public events such as concerts and car races around the world, which is alarming," said Judith Mackay, director of the Asian Consultancy on Tobacco Control.[144]

Internal documents and statements by PMI researchers have contradicted PMI's claims about reduced harm in regard to the IQOS product.[20] For example, in 2018, four PMI researchers who worked for the company stated that the lowered levels of certain substances produced by the IQOS did not automatically translate into the product being safer, even though PMI stated that the IQOS is safer than traditional cigarettes, as 58 substances in IQOS aerosols were found at lower levels than in cigarette smoke.[20]

The tobacco industry claims that smokers will switch to HTPs; however, IQOS users are more likely to smoke and/or use e-cigarettes as well. Among those who have tried or intend to try IQOS, never-smokers equal or outnumber smokers. A review of PMI's research found that smokers did not understand "switching completely" and that IQOS users are not likely to switch completely.[145]

Since 2017, PMI has been promoting its IQOS product in Europe and Asia,[107] where IQOS products are sold as an alternative to regular cigarettes.[146] Outside of an IQOS retail shop in Canada, marketing included a display sign with the message, "Building a Smoke-Free Future".[147][relevant?] Philip Morris International intends to convert its customers in Japan to using heated tobacco products.[148][neutrality is disputed]

There has been significant controversy surrounding the marketing and use of these products.[149] The tobacco companies are using a series of claims in the marketing of HTPs.[43] In both websites and statements to the media and investors, HTPs are presented as less harmful but not risk-free. In a few instances, marketing materials claim that heated tobacco products are potentially helpful to smokers who want to quit. Some media accounts that announced product launches state that HTPs reduce the levels of harmful tobacco components by 90–95% compared to traditional cigarettes, while others emphasise the lack of odor or visible emissions as part of marketing campaigns; as of April 2018[update], there is no evidence to confirm the former claim.[43] However, the public can perceive "lower exposure" claims as lower risk, even if no such claim was made explicitly.[145][opinion] Other marketing claims highlight that these products produce no smoke (i.e., "smoke-free").[43] Implied in these claims, in advertisements and stores globally, is that smokers should switch from traditional cigarettes to these new, allegedly less harmful, products.[43][opinion]

| Product name | Marketing terms | Product appeal |

|---|---|---|

| IQOS | Reduced risk product, innovative | Clean (white, bright blue), stylish, elegant |

| Revo | Reduced risk | Similar sized package as traditional cigarette, white or light grey or gold |

| PAX 2 | Smaller, smarter, sleeker | Design, elegant and fun |

| iFuse | Reduced risk | Packed as traditional cigarette, stylish |

The tobacco industry's use of the "harm reduction" framework also serves to fracture the tobacco control movement, leaving it without a unified voice to communicate with the public, the media and with policy makers on the strategies to advance tobacco control.[43] The concept of harm reduction has traditionally been embraced in several public health fields such as clean needles for injectable drug use and has been explored by some tobacco control experts in the past, with enthusiasm for the possibility of harm reduction growing with the widespread availability of e-cigarettes in certain markets.[43] The tobacco industry frames harm reduction as a common ground with health advocates and a possible entry point to influence legislation and regulation of tobacco products.[43]

The tobacco companies use heated tobacco products as part of their broader political and public relations activities to position them as 'partners' to address the tobacco epidemic rather than as the vectors that are causing it.[43] This is a similar strategy previously used by the tobacco industry to promote itself as a partner of public health in reducing the harms of tobacco, while obfuscating the scientific evidence pointing that harm reduction is achieved through tobacco control policies that decrease consumption.[43]

Regulation

[edit]HTPs are subject to different regulations than traditional cigarettes. For example, some smoking bans do not extend to include them,[44] and in the majority of the countries in which they have been sold, they have been taxed at a lower rate than traditional cigarettes.[150] Tobacco companies have used these products to seek exemptions and relaxations of existing tobacco control policies,[151] and have used them in attempts to influence regulatory policy to sustain and increase their clientele in the midst of decreasing cigarette usage.[151]

In the United States, these products fall under the jurisdiction of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2016.[29] In the same year, Action on Smoking and Health stated in 2016 that "unless and until independent evidence shows that IQOS and similar products are substantially less harmful than smoking then these products should be regulated in the same way as other tobacco products."[49] In 2017, Mitchell H. Katz, director of the Los Angeles County Health Agency, wrote: "There is concern that heat-not-burn tobacco will skirt local ordinances that prevent smoking in public areas."[44] Tobacco control activist Stanton Glantz stated that the US FDA should halt new tobacco products until tobacco companies stop selling traditional cigarettes.[152] It is recommended that indoor-smoking bans for traditional cigarettes be extended to heated tobacco products.[102][who?] It is recommended that marketing of these products, and claims being made about them, should be regulated.[43][who?]

Advertisement for the IQOS product itself is not regulated under the European Union Tobacco Products Directive, though the directive may apply to advertising for the IQOS' tobacco stick.[87] The UK government has been looking into creating a separate category for taxing heated tobacco products.[153]

Due to the alleged belief in heated tobacco harm reduction in Italy, HTPs are exempted from the fiscal regimes of tobacco products. Taxes on them are reduced as much as e-cigarettes, or half of traditional cigarettes. Moreover, the enforcement of various tobacco control regulations is only minimally adopted for HTPs in Italy: health warnings are required to cover only 30% of the heated tobacco product packaging (instead of 65% for traditional cigarettes), without pictorial images; comprehensive smoke-free regulations prohibiting smoking in all public places and workplaces do not apply to HTPs; and advertising and promotions are not banned for them. Epidemiologists Xiaoqiu Liu et al. note the lax enforcement over HTPs have been exploited by the presence of "IQOS embassies" and "IQOS boutiques"—fancy concept stores where IQOS is promoted as a status symbol and free samples are given—and believe the most recognized tobacco control policies in Italy (i.e., price/tax increase, smoking bans, advertising bans, and health warnings) have been compromised by HTPs.[62]

HTPs are not restricted for sale in Israel by the Ministry of Health.[154] The Justice Ministry in Israel agreed with the view of three voluntary organizations that the IQOS is a tobacco product, and that it should be regulated in the same manner as tobacco products.[155] In Israel the IQOS is taxed at the same rate as traditional cigarettes.[156]

Ploom, IQOS, and glo fall under the Tobacco Business Act as tobacco products in Japan because they consist of tobacco leaf.[57] Ploom and IQOS are governed by the Tobacco Industries Act regulations as tobacco products in Japan.[59] The Liberal Democratic Party will deliberate over increasing the tax rate for heated tobacco products in April 2018.[157][needs update]

Electronic tobacco products using dry material are regulated as e-cigarettes in South Korea by the Ministry of Health and Welfare,[158] which are regulated differently than traditional cigarettes for tax reasons.[159] As a result, IQOS are taxed at a lower rate when compared to the 75% incurred on normal cigarettes.[159] Emerging tobacco products are banned in Singapore by the Ministry of Health.[160] China plans to pass legislation to ban the sale of these products to minors, as of 2019.[161]

After IQOS launched a marketing campaign in New Zealand in December 2016, the country's Ministry of Health stated in 2017 that the refill sticks are not legal for sale in New Zealand under the Smoke-free Environments Act 1990.[162] A representative for the company in New Zealand stated that IQOS products comply with the Smoke-Free Environments Act.[163] Three meetings between Ministry of Health officials and people from the tobacco industry were held from 30 May 2017 through 2 June 2017 to "discuss regulation of new tobacco and nicotine-delivery products". In August 2017, the government stated they would initiate a review process before products are sold for heated tobacco products such as IQOS.[164] In 2018, PMI and the Ministry of Health were in a legal dispute over the legality of selling IQOS in New Zealand,[165] before a New Zealand court decided in March that the HEETs sticks used in the IQOS product are legal to sell in the country.[166] Individuals can import heated tobacco products to New Zealand for personal use.[167]

As of 2019[update], 49 countries have permitted the sale of IQOS.[97]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also variously known as a partially combustion heat-not-burn product,[1] heat-not-burn device,[2] heat-not-burn tobacco product (HNB),[3] Heat-not-Burn tobacco product,[4] heat-not-burn cigarette (HC),[5] heat-not-burn cig,[6] HNB tobacco product,[3] HnB tobacco product,[7] HNB product,[8] HnB product,[7] heat-not-burn tobacco device,[9] heat-not-burn system,[10] HnB system,[7] heat-not-burn (HNB) device,[8] heat-not-burn device,[10] HNB device,[8] HnB tobacco device,[11] HnB device,[12] HNB cigarette,[13] heated cigarette,[14] HTP cigarette,[15] cigarette-like product,[16] mini-cigarette,[17] electronic heated tobacco product,[18] electronically-heated cigarette smoking system (EHCSS),[19] electrically heated cigarette smoking system,[20] electrically heated tobacco system,[21] non-combusted cigarette,[22] non-combusted tobacco product,[22] tobacco heating cigarette,[23] tobacco heating product,[23] tobacco heating system (THS),[24][25] smokeless cigarette,[26] smokeless tobacco stick,[27] tobacco stick product,[28] loose-leaf tobacco vaporizer (LLTV),[29] tobacco vaporizer,[30] or T-vapor.[31]

Bibliography

[edit]- "WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2019" (PDF). World Health Organization. July 2019. pp. 1–209.

- McNeill, A; Brose, LS; Calder, R; Bauld, L; Robson, D (February 2018). "Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018" (PDF). UK: Public Health England. pp. 1–243.

- "Regulatory Impact Statement: Regulation of smokeless tobacco and nicotine-delivery products" (PDF). Ministry of Health (New Zealand). 2017. pp. 1–52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2019.

- "Further development of the partial guidelines for implementation of Articles 9 and 10 of the WHO FCTC" (PDF). World Health Organization. 12 July 2016. pp. 1–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "Alternatieve tabaksproducten: harm reduction?" [Alternative tobacco products: harm reduction?] (PDF). Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. 2016. pp. 1–66.

References

[edit]- ^ Leigh, Noel J; Tran, Phillip L; O’Connor, Richard J; Goniewicz, Maciej Lukasz (2018). "Cytotoxic effects of heated tobacco products (HTP) on human bronchial epithelial cells". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): s26–s29. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054317. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6252481. PMID 30185530.

- ^ Kary, Tiffany (18 April 2019). "Philip Morris says it doesn't want you to buy its cigarettes, but will IQOS help it survive?". The Japan Times. Bloomberg News.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jenssen, Brian P.; Walley, Susan C.; McGrath-Morrow, Sharon A. (2017). "Heat-not-Burn Tobacco Products: Tobacco Industry Claims No Substitute for Science". Pediatrics. 141 (1): e20172383. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2383. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 29233936. S2CID 41704475.

- ^ Belushkin, M.; Esposito, M.; Jaccard, G.; Jeannet, C.; Korneliou, A.; Tafin Djoko, D. (2018). "Role of testing standards in smoke-free product assessments". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 98: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2018.06.021. ISSN 0273-2300. PMID 29983383.

- ^ Kamada, Takahiro; Yamashita, Yosuke; Tomioka, Hiromi (2016). "Acute eosinophilic pneumonia following heat-not-burn cigarette smoking". Respirology Case Reports. 4 (6): e00190. doi:10.1002/rcr2.190. ISSN 2051-3380. PMC 5167280. PMID 28031826.

- ^ Meg Neal (2 January 2015). "What Is a Heat-Not-Burn Cigarette and Can It Help You Quit?". Gizmodo.

- ^ a b c Mallock, Nadja; Böss, Lisa; Burk, Robert; Danziger, Martin; Welsch, Tanja; Hahn, Harald; Trieu, Hai-Linh; Hahn, Jürgen; Pieper, Elke; Henkler-Stephani, Frank; Hutzler, Christoph; Luch, Andreas (2018). "Levels of selected analytes in the emissions of "heat not burn" tobacco products that are relevant to assess human health risks". Archives of Toxicology. 92 (6): 2145–2149. doi:10.1007/s00204-018-2215-y. ISSN 0340-5761. PMC 6002459. PMID 29730817.

- ^ Paumgartten, Francisco J.R. (2018). "A critical appraisal of the harm reduction argument for heat-not-burn tobacco products". Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 42: e161. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2018.161. ISSN 1020-4989. PMC 6386018. PMID 31093189.

- ^ a b c d Kaur, Gurjot; Muthumalage, Thivanka; Rahman, Irfan (2018). "Mechanisms of toxicity and biomarkers of flavoring and flavor enhancing chemicals in emerging tobacco and non-tobacco products". Toxicology Letters. 288: 143–155. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.02.025. ISSN 0378-4274. PMC 6549714. PMID 29481849.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Pieper, Elke; Mallock, Nadja; Henkler-Stephani, Frank; Luch, Andreas (2018). "Tabakerhitzer als neues Produkt der Tabakindustrie: Gesundheitliche Risiken" ["Heat not burn" tobacco devices as new tobacco industry products: health risks]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (in German). 61 (11): 1422–1428. doi:10.1007/s00103-018-2823-y. ISSN 1436-9990. PMID 30284624. S2CID 52915909.

This article incorporates text by Elke Pieper, Nadja Mallock, Frank Henkler-Stephani, and Andreas Luch available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Elke Pieper, Nadja Mallock, Frank Henkler-Stephani, and Andreas Luch available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b Caruana, Diane (25 October 2017). "BAT to launch its HnB device in Russia". VapingPost.

- ^ Jenssen, Brian P.; Boykan, Rachel (2019). "Electronic Cigarettes and Youth in the United States: A Call to Action (at the Local, National and Global Levels)". Children. 6 (2): 30. doi:10.3390/children6020030. ISSN 2227-9067. PMC 6406299. PMID 30791645.

- ^ Craver, Richard (2 August 2015). "Reynolds' decision to stop marketing of heated cigarette Revo illustrates challenges in selling adult smokers on new products". Winston-Salem Journal.

- ^ Jeong, Won Tae; Cho, Hyun Ki; Lee, Hyung Ryeol; Song, Ki Hoon; Lim, Heung Bin (2019). "Comparison of the content of tobacco alkaloids and tobacco-specific nitrosamines in 'heat-not-burn' tobacco products before and after aerosol generation". Inhalation Toxicology. 30 (13–14): 527–533. doi:10.1080/08958378.2019.1572840. ISSN 0895-8378. PMID 30741569. S2CID 73436802.

- ^ a b c d e f Staal, Yvonne CM; van de Nobelen, Suzanne; Havermans, Anne; Talhout, Reinskje (2018). "New Tobacco and Tobacco-Related Products: Early Detection of Product Development, Marketing Strategies, and Consumer Interest". JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 4 (2): e55. doi:10.2196/publichealth.7359. ISSN 2369-2960. PMC 5996176. PMID 29807884.

This article incorporates text by Yvonne CM Staal, Suzanne van de Nobelen, Anne Havermans, and Reinskje Talhout available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Yvonne CM Staal, Suzanne van de Nobelen, Anne Havermans, and Reinskje Talhout available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Dautzenberg, B.; Dautzenberg, M.-D. (2018). "Le tabac chauffé : revue systématique de la littérature" [Systematic analysis of the scientific literature on heated tobacco]. Revue des Maladies Respiratoires (in French). 36 (1): 82–103. doi:10.1016/j.rmr.2018.10.010. ISSN 0761-8425. PMID 30429092.

- ^ a b c d e f g St.Helen, Gideon; Jacob III, Peyton; Nardone, Natalie; Benowitz, Neal L (2018). "IQOS: examination of Philip Morris International's claim of reduced exposure". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): s30–s36. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054321. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6252487. PMID 30158205.

This article incorporates text by Gideon St.Helen, Peyton Jacob III, Natalie Nardone, and Neal L Benowitz available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Gideon St.Helen, Peyton Jacob III, Natalie Nardone, and Neal L Benowitz available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b Lindson-Hawley, Nicola; Hartmann-Boyce, Jamie; Fanshawe, Thomas R; Begh, Rachna; Farley, Amanda; Lancaster, Tim (2016). "Interventions to reduce harm from continued tobacco use". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (12): CD005231. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005231.pub3. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6463938. PMID 27734465.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Elias, Jesse; Dutra, Lauren M; St. Helen, Gideon; Ling, Pamela M (2018). "Revolution or redux? Assessing IQOS through a precursor product". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): s102–s110. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054327. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6238084. PMID 30305324.

- ^ Pacitto, A.; Stabile, L.; Scungio, M.; Rizza, V.; Buonanno, G. (2018). "Characterization of airborne particles emitted by an electrically heated tobacco smoking system". Environmental Pollution. 240: 248–254. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.04.137. ISSN 0269-7491. PMID 29747109. S2CID 13711514.

- ^ a b "How are Non-Combusted Cigarettes, Sometimes Called Heat-Not-Burn Products, Different from E-Cigarettes and Cigarettes?". United States Food and Drug Administration. 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d RIVM 2016, p. 36.

- ^ McNeill 2018, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Kaunelienė, Violeta; Meišutovič-Akhtarieva, Marija; Martuzevičius, Dainius (2018). "A review of the impacts of tobacco heating system on indoor air quality versus conventional pollution sources". Chemosphere. 206: 568–578. Bibcode:2018Chmsp.206..568K. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.05.039. ISSN 0045-6535. PMID 29778082.

- ^ a b Haig, Matt (2003). Brand Failures: The Truth about the 100 Biggest Branding Mistakes of All Time. Kogan Page Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7494-4433-4.

- ^ "Philip Morris' Smokeless Tobacco Stick Shouldn't Be Marketed As Safer Than Cigarettes, FDA Panel Says". Kaiser Health News. 26 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Tobacco company charged over importing prohibited product". The New Zealand Herald. 18 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Lopez, Alexa A.; Hiler, Marzena; Maloney, Sarah; Eissenberg, Thomas; Breland, Alison B. (2016). "Expanding clinical laboratory tobacco product evaluation methods to loose-leaf tobacco vaporizers". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 169: 33–40. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.005. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 5140724. PMID 27768968.

- ^ Queloz, Sébastien; Etter, Jean-François (2019). "An online survey of users of tobacco vaporizers, reasons and modes of utilization, perceived advantages and perceived risks". BMC Public Health. 19 (1): 642. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6957-0. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 6537171. PMID 31133009.

This article incorporates text by Sébastien Queloz and Jean-François Etter available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Sébastien Queloz and Jean-François Etter available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Unger, Michael; Unger, Darian W. (2018). "E-cigarettes/electronic nicotine delivery systems: a word of caution on health and new product development". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 10 (S22): S2588–S2592. doi:10.21037/jtd.2018.07.99. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 6178300. PMID 30345095.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Heated tobacco products (HTPs) information sheet". World Health Organization. May 2018.

- ^ a b WHO 2019, p. 54.

- ^ St.Helen, Gideon; Jacob III, Peyton; Nardone, Natalie; Benowitz, Neal L (November 2018). "IQOS: examination of Philip Morris International's claim of reduced exposure". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): s30–s36. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054321. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6252487. PMID 30158205.

- ^ a b c d e Caputi, TL (24 August 2016). "Industry watch: heat-not-burn tobacco products are about to reach their boiling point". Tobacco Control. 26 (5): 609–610. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053264. PMID 27558827. S2CID 46170776.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Li, Gerard; Saad, Sonia; Oliver, Brian; Chen, Hui (2018). "Heat or Burn? Impacts of Intrauterine Tobacco Smoke and E-Cigarette Vapor Exposure on the Offspring's Health Outcome". Toxics. 6 (3): 43. doi:10.3390/toxics6030043. ISSN 2305-6304. PMC 6160993. PMID 30071638.

This article incorporates text by Gerard Li, Sonia Saad, Brian G. Oliver, and Hui Chen available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Gerard Li, Sonia Saad, Brian G. Oliver, and Hui Chen available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b MHNZ 2017, p. 4.

- ^ Marinova, Polina (22 April 2019). "Vaping Startup Pax Labs Raises $420 Million in Funding: Term Sheet for Monday, April 22". Fortune.

- ^ a b WHO 2016, p. 6.

- ^ a b c McNeill 2018, p. 220.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Toxicological evaluation of novel heat-not-burn tobacco products – non-technical summary" (PDF). Committee on Toxicity. 11 December 2017. pp. 1–4.

- ^ a b c d e McNeill 2018, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Bialous, Stella A; Glantz, Stanton A (2018). "Heated tobacco products: another tobacco industry global strategy to slow progress in tobacco control". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): s111–s117. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054340. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6202178. PMID 30209207.

This article incorporates text by Stella A Bialous and Stanton A Glantz available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Stella A Bialous and Stanton A Glantz available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ a b c Rapaport, Lisa (26 May 2017). "'Heat-not-burn' cigarettes still release cancer-causing chemicals". Reuters.

- ^ a b RIVM 2016, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Górski, Paweł (2019). "E-cigarettes or heat-not-burn tobacco products — advantages or disadvantages for the lungs of smokers". Advances in Respiratory Medicine. 87 (2): 123–134. doi:10.5603/ARM.2019.0020. ISSN 2543-6031. PMID 31038725.

- ^ a b McNeill 2018, p. 219.

- ^ a b c d e Kotz, Daniel; Kastaun, Sabrina (2018). "E-Zigaretten und Tabakerhitzer: repräsentative Daten zu Konsumverhalten und assoziierten Faktoren in der deutschen Bevölkerung (die DEBRA-Studie)" [E-cigarettes and heat-not-burn products: representative data on consumer behaviour and associated factors in the German population (the DEBRA study)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz (in German). 61 (11): 1407–1414. doi:10.1007/s00103-018-2827-7. ISSN 1436-9990. PMID 30284626. S2CID 52913095.

- ^ a b c "ASH reaction to new Philip Morris IQOS 'heat not burn' product". ASH UK. 30 November 2016. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Simonavicius, Erikas; McNeill, Ann; Shahab, Lion; Brose, Leonie S. (1 September 2019). "Heat-not-burn tobacco products: a systematic literature review". Tobacco Control. 28 (5): 582–594. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054419. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6824610. PMID 30181382.

- ^ Katz, Mitchell H. (July 2017). "No Smoke—Just Cancer-Causing Chemicals". JAMA Internal Medicine. 177 (7): 1052. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1425. ISSN 2168-6106. PMID 28531245.

- ^ a b McNeill 2018, p. 208.

- ^ McNeill 2018, p. 210.

- ^ Popova, Lucy; Lempert, Lauren Kass; Glantz, Stanton A (November 2018). "Light and mild redux: heated tobacco products' reduced exposure claims are likely to be misunderstood as reduced risk claims". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): s87–s95. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054324. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6202239. PMID 30209208.

- ^ a b MHNZ 2017, p. 5.

- ^ a b "Statement on the toxicological evaluation of novel heat-not-burn tobacco product" (PDF). Committee on Toxicity. 11 December 2017. pp. 1–10.

- ^ a b Tabuchi, Takahiro; Gallus, Silvano; Shinozaki, Tomohiro; Nakaya, Tomoki; Kunugita, Naoki; Colwell, Brian (2018). "Heat-not-burn tobacco product use in Japan: its prevalence, predictors and perceived symptoms from exposure to secondhand heat-not-burn tobacco aerosol". Tobacco Control. 27 (e1): e25–e33. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053947. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6073918. PMID 29248896.

- ^ a b Marynak, Kristy L.; Wang, Teresa W.; King, Brian A.; Agaku, Israel T.; Reimels, Elizabeth A.; Graffunder, Corinne M. (2018). "Awareness and Ever Use of "Heat-Not-Burn" Tobacco Products Among U.S. Adults, 2017". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 55 (4): 551–554. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.031. ISSN 0749-3797. PMID 30033025. S2CID 51708913.

- ^ a b Tabuchi, Takahiro; Kiyohara, Kosuke; Hoshino, Takahiro; Bekki, Kanae; Inaba, Yohei; Kunugita, Naoki (2016). "Awareness and use of electronic cigarettes and heat-not-burn tobacco products in Japan". Addiction. 111 (4): 706–713. doi:10.1111/add.13231. ISSN 0965-2140. PMID 26566956.

- ^ Mulier, Thomas; Chambers, Sam; Liefgreen, Liefgreen (24 March 2016). "Marlboro Kicks Some Ash". Bloomberg News.

- ^ Lasseter, Tom; Wilson, Duff; Wilson, Thomas; Bansal, Paritosh (15 May 2018). "Philip Morris device knows a lot about your smoking habit". Reuters.

- ^ a b c d Liu, Xiaoqiu; Lugo, Alessandra; Spizzichino, Lorenzo; Tabuchi, Takahiro; Gorini, Giuseppe; Gallus, Silvano (2018). "Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Products Are Getting Hot in Italy". Journal of Epidemiology. 28 (5): 274–275. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20180040. ISSN 0917-5040. PMC 5911679. PMID 29657258.

This article incorporates text by Xiaoqiu Liu, Alessandra Lugo, Lorenzo Spizzichino, Takahiro Tabuchi, Giuseppe Gorini, and Silvano Gallus available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Xiaoqiu Liu, Alessandra Lugo, Lorenzo Spizzichino, Takahiro Tabuchi, Giuseppe Gorini, and Silvano Gallus available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ "What Do We Know About Heated Tobacco Products?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 March 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Ziedonis, Douglas; Das, Smita; Larkin, Celine (2017). "Tobacco use disorder and treatment: New challenges and opportunities". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 19 (3): 271–80. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.3/dziedonis. PMC 5741110. PMID 29302224.

- ^ England, Lucinda J.; Kim, Shin Y.; Tomar, Scott L; Ray, Cecily S; Gupta, Prakash C.; Eissenberg, Thomas; Cnattingius, Sven; Bernert, John T.; Tita, Alan Thevenet N.; Winn, Deborah M.; Djordjevic, Mirjana V.; Lambe, Mats; Stamilio, David; Chipato, Tsungai; Tolosa, Jorge E. (2010). "Non-cigarette tobacco use among women and adverse pregnancy outcomes". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 89 (4): 454–464. doi:10.3109/00016341003605719. ISSN 0001-6349. PMC 5881107. PMID 20225987.

- ^ Forster, Mark; Liu, Chuan; Duke, Martin G; McAdam, Kevin G; Proctor, Christopher J (2015). "An experimental method to study emissions from heated tobacco between 100-200°C". Chemistry Central Journal. 9 (1): 20. doi:10.1186/s13065-015-0096-1. ISSN 1752-153X. PMC 4418098. PMID 25941536.

- ^ Davis, Barbara; Williams, Monique; Talbot, Prue (20 February 2018). "iQOS: evidence of pyrolysis and release of a toxicant from plastic". Tobacco Control. 28 (1): tobaccocontrol–2017–054104. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054104. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 29535257. S2CID 3874502.

- ^ Elias, Jesse; Ling, Pamela M (2018). "Invisible smoke: third-party endorsement and the resurrection of heat-not-burn tobacco products". Tobacco Control. 27 (Suppl 1): s96–s101. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054433. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 6238082. PMID 29875153.

- ^ Parker-Pope, Tara (10 February 2001). ""Safer" Cigarettes: A History". PBS.

- ^ McGill, Douglas C (19 November 1988). "'Smokeless' Cigarette's Hapless Start". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ Hilts, Philip J. (27 November 1994). "Little Smoke, Little Tar, but Full Dose of Nicotine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ a b O'Connell, Dominic (30 November 2016). "Philip Morris could stop making conventional cigarettes". BBC News.

- ^ a b c Anderson, S J; Ling, P M (2008). ""And they told two friends...and so on": RJ Reynolds' viral marketing of Eclipse and its potential to mislead the public". Tobacco Control. 17 (4): 222–229. doi:10.1136/tc.2007.024273. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 2845302. PMID 18332064.

- ^ Haig, Matt (2005). Brand Failures: The Truth about the 100 Biggest Branding Mistakes of All Time. Kogan Page Publishers. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-0-7494-4433-4.

- ^ Fisher, Daniel (29 May 2014). "Is This The Cigarette Of The Future, And Will The FDA Let You Buy It?". Forbes.

- ^ "New heat-not-burn brand from RAI". Tobacco Journal International. 5 January 2015.

- ^ a b Craver, Richard (28 July 2015). "Reynolds ends Revo test market in Wisconsin". Winston-Salem Journal.

- ^ "Reynolds launching heat-not-burn cigarette". CBS News. Associated Press. 14 November 2014.

- ^ US 9486013, Sebastian, Andries Don; Conner, Billy Tyrone & Banerjee, Chandra K. et al., "Segmented smoking article with foamed insulation material", published 2016-11-08, assigned to R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.

- ^ Pollack, Juddan (27 October 1997). "Philip Morris tries smokeless Accord: tobacco marketer, cautious about brand, doing 'consumer research'". Ad Age.

- ^ "Anti-smoking body attacks smokeless cigarette device". Tobacco Journal International. 11 December 2007.

- ^ Houston, Cameron (27 June 2007). "Revealed: tobacco giant's secret new weapon in the age of smoking bans". The Age.

- ^ Lubin, Gus (25 June 2012). "Philip Morris Is Releasing A Bunch Of Crazy New Cigarettes". Business Insider.

- ^ Cooper, Ted (1 February 2014). "Why Philip Morris International's New Heated Products Will Do Better Than Its Last Attempt". The Motley Fool.

- ^ MacGuill, Shane (23 January 2014). "Has Philip Morris Learned from Heat-not-Burn Tobacco's Past?". Euromonitor International. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Davies, Rob; Monaghan, Angela (30 November 2016). "Philip Morris's vision of cigarette-free future met with scepticism". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e Harlay, Jérôme (9 November 2016). "What you need to know about Heat-not-Burn (HNB) cigarettes". VapingPost.

- ^ "10 Best Weed Vaporizers to Buy in 2019". Esquire. 11 May 2019.

- ^ Crist, Ry (20 April 2019). "Weed tech heats up with a new smart vaporizer from Apple, Microsoft alums". CNET.

- ^ "BAT finds strong Japan demand for its Glo smokeless tobacco device". The Japan Times. Reuters. 22 March 2017.

- ^ a b Caruana, Diane (25 September 2018). "BAT Launches Glo in Ukraine". VapingPost.

- ^ Caplinger, Dan (31 May 2017). "Here's Why the Worst Might Be Yet to Come for Philip Morris International". The Motley Fool.

- ^ "Innovation Drives BAT's $47 Billion Bid -- WSJ". ADVFN. 24 October 2016.

- ^ Felberbaum, Michael (26 June 2014). "Philip Morris Int'l to Sell Marlboro HeatSticks". Salon. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 28 June 2014.

- ^ Caplinger, Dan (23 November 2015). "5 Things Every Philip Morris Investor Should Know". The Motley Fool.

- ^ Nathan, Ralph (12 October 2016). "Why Philip Morris's iQOS Sales in Japan Are Promising". Market Realist.

- ^ a b c d LaVito, Angelica (4 October 2019). "Altria launches Iqos tobacco device in US, and the timing couldn't be better". CNBC.

- ^ Mulier, Thomas; Thesing, Gabi (26 June 2014). "Philip Morris Sees $700 Million Boost From iQOS Smoking Device". Bloomberg News.

- ^ Uranaka, Taiga; Ando, Ritsuko (22 October 2018). "Philip Morris Aims to Revive Japan Sales With Cheaper Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco". U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ LaVito, Angelica (22 October 2018). "Philip Morris unveils new smokeless cigarettes in a bid to rev up sales". CNBC.

- ^ Hyo-sik, Lee (17 May 2017). "Philip Morris unveils smoke-free cigarette in Korea". The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d Auer, Reto; Concha-Lozano, Nicolas; Jacot-Sadowski, Isabelle; Cornuz, Jacques; Berthet, Aurélie (1 July 2017). "Heat-Not-Burn Tobacco Cigarettes: Smoke by Any Other Name". JAMA Internal Medicine. 177 (7): 1050–1052. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1419. ISSN 2168-6106. PMC 5543320. PMID 28531246.

- ^ Duprey, Rich (9 December 2017). "Will 2018 Be Philip Morris International Inc's Best Year Yet?". Billings Gazette.

- ^ Rossel, Stefanie (1 June 2016). "All eyes on iQOS". Tobacco Reporter.

- ^ Tai, Mariko (31 August 2015). "Philip Morris rolls out iQOS smokeless smokes". Nikkei Asian Review.

- ^ Kopa, Paulina Natalia; Pawliczak, Rafał (2019). "IQOS – a heat-not-burn (HnB) tobacco product – chemical composition and possible impact on oxidative stress and inflammatory response. A Systematic Review". Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods. 30 (2): 81–87. doi:10.1080/15376516.2019.1669245. ISSN 1537-6516. PMID 31532297. S2CID 202673535.

- ^ a b Drope, Jeffrey; Cahn, Zachary; Kennedy, Rosemary; Liber, Alex C.; Stoklosa, Michal; Henson, Rosemarie; Douglas, Clifford E.; Drope, Jacqui (2017). "Key issues surrounding the health impacts of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and other sources of nicotine". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 67 (6): 449–471. doi:10.3322/caac.21413. ISSN 0007-9235. PMID 28961314. S2CID 32928770.

- ^ Dautzenberg, B.; Dautzenberg, M.-D. (11 November 2018). "[Systematic analysis of the scientific literature on heated tobacco]". Revue des Maladies Respiratoires. 36 (1): 82–103. doi:10.1016/j.rmr.2018.10.010. ISSN 1776-2588. PMID 30429092. S2CID 239333927.

- ^ "Addictive nicotine and harmful substances also present in heated tobacco". Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. 15 May 2018.

- ^ Hendlin, Yogi Hale; Elias, Jesse; Ling, Pamela M. (2017). "The Pharmaceuticalization of the Tobacco Industry". Annals of Internal Medicine. 167 (4): 278–280. doi:10.7326/M17-0759. ISSN 0003-4819. PMC 5568794. PMID 28715843.

- ^ Caplinger, Dan (26 May 2017). "The FDA Moves Forward With Philip Morris iQOS Review". The Motley Fool.

- ^ Lasseter, Tom; Bansal, Paritosh; Wilson, Thomas; Miyazaki, Ami; Wilson, Duff; Kalra, Aditya (20 December 2017). "Scientists describe problems in Philip Morris e-cigarette experiments". Reuters.

- ^ "FDA Panel Gives Qualified Support To Claims For". National Public Radio. 25 January 2018.

- ^ a b "FDA permits sale of IQOS Tobacco Heating System through premarket tobacco product application pathway". Food and Drug Administration. 30 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Consumer-Centric Vaping". Convenience Store Decisions. Harbor Communications. 4 March 2015.

- ^ CSD Staff (4 March 2015). "Consumer-Centric Vaping". Convenience Store Decisions. Harbor Communications.

- ^ "The iSmoke OneHitter, iSmoke "3-in-1" and iSmoke Oven join portfolio". Convenience Store News. 2017.

- ^ a b c Schmid, Thomas (6 March 2019). "Heat-Not-Burn: Back to Tobacco". Tobacco Asia.

- ^ a b Song Seung-hyun (7 November 2017). "KT&G launches e-cigarette brand to take on foreign rivals". The Investor.

- ^ "KT&G launches sales of new tobacco-heating device". Yonhap News Agency. 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b c "New HNB Device from China Tobacco". Tobacco Asia. 30 May 2019.

- ^ Biggs, John (17 June 2012). "Smoke Up: An Interview With The Creator Of The Ultracool Pax Vaporizer". TechCrunch.

- ^ Lavrinc, Damon (1 July 2013). "Review: Ploom Model Two". Wired.

- ^ Adam Clark Estes (23 July 2015). "Pax 2 Vaporizer Review: It's Like Smoking In the Future". Gizmodo.

- ^ Stenovec, Tim (12 March 2016). "How two guys from Stanford built the 'iPhone of vaporizers'". Business Insider.

- ^ Taylor, Chris (19 June 2018). "Want to microdose marijuana? This company is making it easier for you". Mashable.

- ^ Rossel, Stefanie (1 July 2016). "Blending nature and technology". Tobacco Reporter.

- ^ Tuinstra, Taco (26 January 2016). "JT announces launch of next-generation Ploom". Tobacco Reporter.

- ^ Uranaka, Taiga (16 January 2019). "Japan Tobacco ratchets up smokeless war with new products". Reuters.