Health communication

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Health communication is the study and practice of communicating promotional health information, such as in public health campaigns, health education, and between doctor and patient.[1] The purpose of disseminating health information is to influence personal health choices by improving health literacy. Health communication is a unique niche in healthcare that allows professionals to use communication strategies to inform and influence decisions and actions of the public to improve health.

Because effective health communication must be tailored for the audience and the situation [2] research into health communication seeks to refine communication strategies to inform people about ways to enhance health or avoid specific health risks.[3] Academically, health communication is a discipline within communication studies.[1] The field of health communication has been growing and evolving in recent years. The field plays a role in health advancement with patients and medical professionals. Research shows health communication helps with behavioral change[4] in humans and conveys specific policies with practices that can serve as an alternative to certain unhealthy behaviors. The health communication field is considered more a multidisciplinary field of research theory[4] to encourage actions, practices, and evidence that contribute to improving the healthcare field. The use of various skills and techniques to enhance change among patients and many others and focus on behavioral and social changes to improve the public health outcome.[4]

Health communication may variously seek to:

- increase audience knowledge and awareness of a health issue[5]

- influence behaviors and attitudes toward a health issue

- demonstrate healthy practices

- demonstrate the benefits of behavior changes to public health outcomes

- advocate a position on a health issue or policy

- increase demand or support for health services

- argue against misconceptions about health[6]

- improve patient-provider dialogue[7]

- enhance effectiveness in health care teams[8]

Definition and origins

[edit]Health communication is an area of research that focuses on the scope and implications of meaningful expressions and messages in situations or circumstances associated with health and health care.[9] Health communication is considered an interdisciplinary field of research, encompassing medical science, public health, and communication studies.

Health communication aims to increase knowledge by letting the public know what to do in a health crisis, be able to handle it smoothly and clearly without as much panic as when first discovering an illness or disease unknown to the public. Which research has shown that it can lead to behavioral change. [10] It emphasizes that communication involves verbal and non-verbal messages between a sender and receiver. Effective communication is crucial for health-related outcomes and even situational analysis, which includes evaluating the audience to help guide the choice of appropriate messages and channels applied. [10]

General health communication has origins dating as far back as the 4th century BC. Ancient Greek physician Hippocrates first began writing about the connection between diseases and the environment, laying the foundation for the modern understanding of transmittable diseases. Additionally, during the late 18th century, British Navy surgeon James Lind began formally documenting mortality among sailors in his medical publication Treatise of the Scurvy in 1753.[11]

The term health communications was used in 1961 when the National Health Council organized a National Health Forum to discuss challenges faced in the communications of health information (Helen, 1962).[12] The term was used again in 1962 when Surgeon General Luther Terry organized a conference on health communication to discuss how various techniques can make health information available to the public (US Department of Health Education and Welfare, 1963).[13] The term was adopted by members of an interest group at ICA, International Communication Association in 1975. The research of health communication surrounds the development of effective messages about health, the dissemination of health-related information through broadcast, print, and electronic media, and the role of inter personal relationships in health communities. At the core of all of the communication is the idea of health and the emphasis of health. The goal of health communication research is to identify and provide better and more effective communication strategies that will improve the overall health of society. (Atkin & Silk, page 489)[14]

Research

[edit]

There are many purposes and reasons why health communication research is important and how it betters the health care field. The training programs of Health Care Professionals, or HCP, can be adapted and developed based on health communication research. (Atkin & Silk, 495)[14] One major example of a specialized research program is the Health Communication Research Unit at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, aimed at studying the challenges to heath communication faced by cultural diversity.[15] Due to there being a diverse culture that makes up the group of patients within the health care field, communication to other cultures has been taught and has been made a focus in health care training classes. Research suggests that nonverbal and verbal communication between health care professionals and patient can lead to improved patient outcomes.[16] According to Atkin and Silk on page 496[14] some health care facilities, like hospitals are providing training and education materials to patients. The goal of hospitals doing this is to allow for patients to have a better outcome due to better communication skills. Over the years, there has been much research done on health communication. For example, researchers want to know if people are more effectively motivated by a positive message versus a negative message. Researchers examine ideas like, are people better motivated by ideas of wealth and safety or an idea of illness and death. Researchers are examining which dimensions of persuasive incentives are most influential: physical health versus economic, versus psychological, versus moral, versus social. (Atkin & Silk, 497)[14] Impact of the Health Campaign-After research has been conducted and analyzed on the effects of health communication, it can be concluded that a health communication campaign that is requiring a behavior change causes the desired behavior change in about 7%-10% or more in the people who are in the campaign site than those who are in the control group. Also, the effects are stronger for adoption of a new behavior than cessation of a current behavior, about 12% higher.

When assessing how affective a health campaign is, the key determinant is the degree of audience reception, the quality and quantity of the message, the dissemination channels, and the larger communication environment. It is possible that an audience can be more receptive to some messages than others. The media channel and how the message is reached by the audience can affect the effectiveness of the health campaign. (Atkin & Silk, page 498)[14]

Training

[edit]Health communication professionals are specifically trained in methods and strategies for effective communication of public health messages, with qualifications in research, strategic development, and evaluating effectiveness.[2] Health communication is taught in master's and doctoral programs.[6][17] The Coalition for Health Communication maintains a list of such programs.[18]

The International Association for Communication in Healthcare (EACH) is a global organization aimed at improving the health communication sector between practitioners and patients. One major program EACH offers is "tEACH". tEACH is a specific subgroup focused on aiding teachers across the globe with tools and resources for promoting proper healthcare communication. The program consists of training modules, organized conferences, as well as project support.[19]

Scholars and practitioners in health communication are often trained in disciplines such as communication studies, sociology, psychology, public health, or medicine and then focus within their field on either health or communication. Practitioners are pragmatic and draw from social-scientific scholarship, theories from the humanities, and professional fields such as education, management, law and marketing (Maibach 2008). Professionals trained in health communication encounter a wide range of employment opportunities spanning between the public, private, and volunteer sectors and have the opportunity for a large amount of career mobility.[17] Examples of jobs in each of these categories include federal, state, and local health departments in the public sector, Pharmaceutical companies and large corporations in the private sector, and various non-profit organizations such as the American Cancer Society and the American Heart Association in the volunteer sector.

Overview

[edit]International Communication Association officially recognized health communication in 1975; in 1997, the American Public Health Association categorized health communication as a discipline of Public Health Education and Health Promotion.[6]

Careers in the field of health communication range widely between the public, private, and volunteer sectors and professionals of health communication are distinctively trained to conduct communication research, develop successful and repeatable campaigns for health promotion and advocacy, and to evaluate how effective these strategies have been for future campaigns.[2]

Clear communication is essential to successful public health practice at every level of the ecological model: intrapersonal, interpersonal, group, organizational, and societal. In each instance of health communication, there must be careful deliberation concerning the appropriate channel for messages to best reach the target audience, ranging from face-to-face interactions to television, Internet, and other forms of mass media.[20] The recent explosion of new Internet communication technologies, particularly through the development of health websites (such as MedlinePlus, Health finder, and WebMD), online support groups (such as the Association for Cancer Online Resources), web portals, tailored information systems, telehealth programs, electronic health records, social networking, and mobile devices (cell phones, PDAs, etc.) means that the potential media are ever changing.

The social and cultural contexts in which health communication occurs are also widely diverse and can include (but are not limited to) homes, schools, doctor's offices, and workplaces, and messages must consider the variant levels of health literacy and education of their audience, as well as demographics, values, socioeconomic issues, and many other factors that may influence effective communication.[2]

During the Covid-19 pandemic, it became clear that major topics in health communication include misinformation as well as the role of communication in addressing health inequities. Misinformation[21] had a major impact on vaccine acceptance and people's adoption of pandemic prevention measures. Not only does misinformation contribute to vaccine hesitancy, social discrimination and stigma, but is also affected by the ongoing global trust[22] crisis in science and official sources. This further contributes to behavioral and social divides and to increasing long-standing inequities.[23] A narrative shift is essential to address these issues.

Critical health communication

[edit]Critical health communication refers to scholarship that interrogates "how meanings and enactments of health are tied to issues of power through the systematic construction and maintenance of inequalities."[24] It examines links with culture, resources, and other social structures.[24] It is distinct from mainstream Health Communication in its emphasis on qualitative and interpretive methods, and its attention to the ideological processes that underpin shared understandings of health. Unlike much mainstream Health Communication, most Critical Health Communication holds that simply circulating better quality, or more visible message about health is not enough to meaningfully influence health outcomes or correct health care disparities. The first comprehensive review of Critical Health Communication was published in 2008,[25] and since then the volume of Health Communication research taking a critical approach has steadily increased.

Strategies and methods

[edit]Tailoring a health message is one strategy for persuasive health communication.[26] For messages of health communication to reach selected audiences accurately and quickly, health communication professionals must assemble a collection of superior and audience appropriate information that target population segments. Understanding the audience for the information is critical to effective delivery.

Communication is an enigma that is detrimental to the healthcare world and to the resulting health of a patient. Communication is an activity that involves oral speech, voice, tone, nonverbal body language, listening and more. It is a process for a mutual understanding to come at hand during interpersonal connections. A patient's communication with their healthcare team and vice versa, affects the outcome of their health. Strong, clear, and positive relationships with physicians can chronically improve and increase the condition of a certain patient. Through two approaches, the biomedical model and the biopsychosocial model; this can be successfully achieved. Evidence has shown that communication and its traditions have altered throughout the years. With the use of many new discoveries and the changes within our technology market, communication has severely improved and become instantaneous.

Communicators need to continually synthesize knowledge from a range of other scholarly disciplines including marketing, psychology, and behavioral sciences.[2] Once this information has been collected, professionals can choose from a variety of methods and strategies of communication that they believe would best convey their message. These methods include campaigns, entertainment advocacy, media advocacy, new technologies, and interpersonal communication.[6]

Campaigns

[edit]A health campaign is an organization to change certain behaviors or show a different point of view on something in to persuade someone. Research shows how campaigns have effectively encouraged people to change an unhealthy health behavior[27] that can potentially worsen their health. Health communication has been utilized to help address health conditions or habits contributing to adverse fatality-related effects. The Mediated campaign is the use of media to communicate with a broad audience and impart Knowledge or convince people of a particular point of view based on research that has contributed to the success of the behavior change campaign.[27] A vast media campaign that includes bus signs, panel street signs, radio ads, television ads, and other advertisements with the primary objective of showing people a sign that includes the specific recommendation on fruit and vegetable consumption.[28] Another method that was employed was calling random numbers to find out people's opinions regarding a balanced diet and regular exercise. "The percentage of respondents who considered walking to be very important increased."[28] The recall's findings indicate that people's attitudes regarding walking and the eating of fruits and vegetables were generally more positive. The media has enhanced the campaign's attitude toward these two fundamental health-related behavioral changes. The results support that using media coverage can promote campaigns for healthy lifestyles.

Health Communication campaigns are arguably the most utilized and effective method for spreading public health messages, especially in endorsing disease prevention (e.g. cancer, HIV/AIDS) and in general health promotion and wellness (e.g. family planning, reproductive health).[20] The Institute of Medicine argues that health communication campaigns tend to organize their message for a diverse audience in one of three ways:[6]

- By catering to the common denominator within the audience

- By creating one central message and then later making systematic alterations in order to better reach a certain audience segment, while retaining the same central message

- By creating distinctly different messages for different audience segments

Both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and scholars of health communication emphasize the importance of strategic planning throughout a campaign. This includes a variety of steps to ensure a well-developed message is being communicated:[3]

- Reviewing background information to define what the problem is and who is affected by the problem

- Setting communication objectives and proposing a plan to meet the wanted outcome

- Analyze the target audience by determining interests, attitudes, behaviors, benefits, and barriers

- Select channels and materials for communication in relation to what will most effectively reach audiences

- Develop and pretest message concepts to determine understanding, acceptance, and reaction to the message

- Implement communication with selected audience and monitor exposures and reactions to the message

- Ensure information is available in the language of intended audiences[29]

- Assess the outcome and evaluate the effectiveness and impact of the campaign, noting if changes need to be made

Historical campaigns

[edit]2014 African Ebola Outbreak

In 2018, four years after the first major outbreak of Ebola in Western Africa, the Democratic Republic of Congo and UNICEF partnered together to raise awareness about the deadly virus in a multi-national effort reaching around 800,000 people in affected areas. Communication efforts about preventive measures and safe practices regarding the virus included home visits by nurses, campaigns in major cities and markets, and broadcasting through mass media.[30]

China's 2019 "Zero-COVID" Policy

Following the global outbreak of the Covid-19 Pandemic in 2019, the Chinese government under Xi Jinping issued a major health communication campaign titled the "Zero-COVID" policy. This new set of restrictions included lockdowns, stricter contact-tracing mechanisms, and increased testing to Chinese citizens was aimed at attempting to stop the spread of Covid-19. The policy was relatively successful at slowing the spread of the virus, however, it did cause major food shortages and other problems.[31]

World Health Organization's (WHO) Heatwave Initiative

The WHO's "Heatwave and Health" initiative was launched in 2021 in co-partnership with the Pan American Health Organization aimed at educating the public in South and Central-American countries about the hazards present from heatwaves. Awareness including what to do before and during a heatwave was communicated in the form of webinars, information YouTube videos, and website articles. The campaign additionally focused on developing and/or strengthening local governments knowledge on the matter and establishing public safety plans when heatwaves are imminent.[32]

COVID-19 In the United States

[edit]When the cases of COVID-19 were first identified in the United States, the general public was unsure of how to react to this unprecedented and ever evolving virus. This resulted in a world-breaking number of deaths over 1.2 million throughout the course of 2020 to 2023. These unpredictable abundant deaths led hospitals to feel misguided on how to treat such numerous amounts of people with few resources or information to go off of. Lack of information and the highly contagious and deadly nature of the disease posed a critical health communication need. [33] Despite that, many have concluded based off other health crisis situations in the past, that four main factors were needed for health communicators to discuss to put people's minds at ease to get through this troubling new time and pandemic. These factors include: 1) Being honest to the public, discussing current findings and what information is unknown. 2) Being persistent and specific to detail, making sure to let patients know the severity of the illness, even if not much information is known. 3) Provide confidence in decision-making, helping people become less fearful and safer on experts' strategies. 4) Recognize concerned behavior among the public, reassure them, and give efficient explanations of new findings in a more compassionate way to avoid more panic across the country. [33]

These variables have been shown not only to calm public outrage but also to encourage social change in behavior. [33] Several health communicators and campaigns encourage this by suggesting taking action towards the surroundings of our community, involving hand sanitizers in consistently noticeable places like bathrooms, public parks, restaurants, etc. Health communicators explained that providing the pertinent information, including definitions of contagious illness, helps the public to better understand the severity of the virus and protocols to avoid spreading it. Preventing COVID-19 from spreading also requires persistent behavioral and attitude changes over time to regulate hygienic consistency towards the public. [33]

Public health officials soon used similar, practical information on the appropriate use of hygiene to prevent the virus from expanding for good. This shifted them to the use of vaccines once established, providing another development that offered more concern on the needed numbers of vaccines to get rid of the contagious growth of the pandemic. [34] New health communication crisis emerged as skepticism arose from the expedited manner in which the vaccine was created and approved. As the need for vaccines for COVID-19 increased, more arose the question from the public on whether the vaccine was trustworthy and skeptical about taking it, mainly due to its unordinary speed of development. [34]

Vaccine Hesitancy

[edit]Vaccines are a major influence in the health industry towards preventing illness, highlighting the need to communicate on why it is important to have one. A study conducted by the Strategic Advisory Group of Exerts on Immunization (SAGE) worked to see if vaccine hesitancy was determined by poor communication given to the public. [35] They found that health communication did in fact play a role in making a significant difference on individuals getting or choosing to get vaccines to better impact their health. The research discovers that increase vaccinations involves a proper explanation and details on why vaccines are beneficial. In addition, there needs to be preparation beforehand on communication about what to expect. [35]

Giving the public honest information through presentations, medical consensuses, pro-vaccine messages, and stating personal risks can improve behavioral change of the public towards vaccines. This was especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was the third leading cause in America. [34]

The prevention of cigarette smoking

[edit]Cigarette prevention programs have been provided to students from grades 6 to 8, which decreases student smoking at grade school.[36] The study found that there was a long-term effect when smoking prevention was combined with other factors in a particular channel that influenced the youth. However, the effects of smoking prevention varied. The Study's findings indicate that programs are implemented more effectively when they target youth through the media. The study involved two groups of students: one group received extensive media production through the school program, while the other only received the program for four years. The purpose of the program was to change the smoking behavior of the participants by emphasizing the benefits of quitting smoking, precisely the skill for refusing cigarettes and the perception for people their age not to smoke.[36] A survey of the students was done at the end of the year, and it had a lasting effect on their perception of smoking. Furthermore, research demonstrates that widespread anti-tobacco media efforts in conjunction with other anti-tobacco control measures are associated with a decrease in smoking rates as well as an increase in the rate of smoking cessation.[37] The study reveals, "the prevalence of smokers in the United States has declined over the past 40 years".[37] The media campaign focuses on the success of smoking reduction. The campaign promotes the idea that people who are "exposed to the message have the motivation to seek additional information for quitting"[37] and offers people who are attempting to quit the chance to be able to sustain self-restrain from smoking.[37]

American smallpox epidemic

[edit]In 1721, health communication was used to mitigate the smallpox epidemic in Boston. Cotton Mather, a political leader, used pamphlets and speeches to promote inoculation of smallpox.[38][39]

Alcohol abuse

[edit]Alcohol abuse has been a problem within society for about as long as alcohol has been around. In the 19th century, the Women's Christian Temperance Union led a movement against alcohol abuse. They utilized mass communication to communicate the desired message. Newspapers and magazines allowed for the promotion of the anti-alcohol movement.[38]

Cardiovascular disease

[edit]Three-community study and the five-city project were experimental campaigns to inform middle-aged men about the causes of cardiovascular disease. Health messages were communicated via television, radio, newspaper, cookbooks, booklets, and bus cards. The three "communities" comprised three experimental communication strategies: a media-only campaign, a media campaign supplemented with face-to-face communication, and a no-intervention control group. The experimented revealed that after one year, the most informed at-risk men were those in the second experimental group: they men consumed the media campaign and were attended by a health care provider.

STD Prevention and Regulation

[edit]Many campaigns and studies involving STD prevention were reviewed to see what the most effective exposure and communication strategies were to stop the spread of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs). [40] All campaigns researched that were well-managed and structured had similar results in which individuals who were more exposed to STD prevention methods and communication had long-lasting effects on their target audience. These effects included having safer-sex discussions, reducing sex partners, and HIV testing. Constant delivery of STD prevention towards the campaign’s intended research also led them to similarly provide a call-to-action to individuals to make sure they properly communicate on sex, have access to support, use condoms consistently, and, most importantly, get tested. [40]

Communication channels

[edit]Entertainment media

[edit]Using the entertainment industry as a platform for advocating health information and education is a communication strategy that has become increasingly popular. The most utilized strategy is for health communication professionals to create partnerships with storyline creators so that public health information can be incorporated into within the plot of a television show. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has formed a strong partnership with Hollywood, Health, and Society, at the University of Southern California Norman Lear Center to continue to produce new storylines on television and in film studios that will help to promote public health information.[3] Some of the resources provided with this partnership include comprehensive "tip sheets" to provide writers with easy to access and trustworthy information on health issues, and meetings and panels to discuss new information and resources. Some of the most notable examples of this method of communication in recent years have been with the films Contagion and I Am Legend in understanding the spread of disease, NBC's series Parenthood in Asperger's Syndrome, and with the CW's series 90210 and spreading cancer awareness. More recently, film festivals and competitions focused specifically on health films have been organized by the American Public Health Association, the International Health Film Festival, the Global Health Film Initiative of the Royal Society of Medicine and the Public Health Film Society.[41][42][43][44]

Writers and storyline developers have an increased motivation to continue to incorporate public health information into their scripts with the creation of the Sentinel for Health Awards in 2000, which honors storylines that effectively promote health topics and audience awareness of public health issues.[3] Surveys conducted by Porter Novelli in 2001 reported many interesting statistics on the effectiveness of this strategy, such as that over half of regular prime time and daytime drama viewers have reported that they have learned something about health promotion or disease prevention from a TV show.[6] Amongst this data, minority groups are significantly represented with well over half of African American and Hispanic viewers stating that they had either taken some form of preventative action after hearing about a health issue on TV, or that a TV storyline helped them to provide vital health information to a friend or family member.

Direct marketing

[edit]

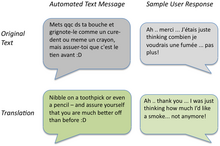

Media advocacy use strategic mass media tools combined with widespread organization in order to advocate for healthy public policies or lifestyles.[6] This can include the use of text messaging and email to spread messages from person to person, and using social networking venues to promote health information to a wide-ranging audience. As technologies expand, the platforms for health communication through media advocacy will undoubtedly expand as well.

Social media

[edit]Social media consists of websites and applications that enable users to create and share content including communication regarding health. As technology continues to evolve it expands the access to health information. Social media platforms allow for the distribution of health information in real time to millions of people. This instant communication has resulted in a dramatic increase of social media being used as a means to connect about health on a global level. In recent years the upward trend to use social media during disaster and crisis times to share public health concerns can be followed. Using social media to upload content about health communication can also result in the rapid spread of misinformation. Many of these platforms have implemented fact checking statements to assist in ensuring information shared is credible.

Interpersonal communication

[edit]Health communication relies on strong interpersonal communication in order to influence health decisions and behaviours. The most important of these relationships are the connection and interaction between an individual and their health care provider (e.g., physician, therapist, pharmacist) and an individual's social support system (family, friends, community). These connections can positively influence the individual's decision to make healthy choices.[6] Patients are more prone to listen when they feel invested emotionally into the situation. If they feel as if they understand what is being said, they are more prone to make objective decisions based on the information heard. Two of the most prominent areas of study in interpersonal health communication are the patient-centered and the relationship centered models of care.[45]

Types of interpersonal health communication model

[edit]Patient-centered model

[edit]The Patient-centered Model focuses on the patient's understanding from the patient perspective.[46] Healthcare professionals pay close attention to patients' worries, feelings, and opinions. In the patient care-centered model, given that the patient participates in developing, planning, and overseeing their care, the healthcare provider views them as team members.[47] It also shows how the healthcare team views the patient as a fellow member who can be helped to achieve a specific objective with a clear vision by exchanging information.

As patient-centered communication and connection are essential, interruptions in health communication are researched. Healthcare professionals are given guidelines to adhere to since interruptions could render the patient-centered model less effective. Research shows when a patient and a healthcare provider are conversing about care, the patient takes about two to three minutes[48] to express what they want to talk about, especially when the provider asks a question that requires them to be clear and detailed (Naughton). The healthcare provider interrupts what the patient is saying after about 23 seconds on average.[48] A study differentiated between interruptions that are cooperative and disruptive.[49] It implies that interruptions don't necessarily have to be intrusive they can also be cooperative, which means that the interruptions can be constitutive and, thus, can result in a continuance of the conversion process, In the study 84 natural interactions between the physicians and Patient[49] the primary goal of classifying the interruption as cooperative or intrusive was conducted. The results show that 82.9% of 2,405 interruptions were cooperative instead of intrusive.[49] Overall, the patient-centered model seeks to minimize disruptions in general. Offering medical professionals training programs based on the patient-centered model of health communication demonstrates the emphasis on interruption, with the main practice suggestion being that physicians should avoid interrupting the patient early in the interview.[50]

Relationship centered model

[edit]Relationship-centered care is characterized by the contributions of teamwork and understanding made between the patients and the physicians and their respective perceptions of the value of their relationships. The patient-medical professional relationship continues to be crucial. For the patient to obtain relationship-based assistance, the clinical provider should involve the patient, family members, and other clinicians when making decisions under the relationship-centered care paradigm.[51] While a relationship-based center developed to comprehend the patient, the relationship care center's methodology begins with implementing a patient care center that centralizes the patient.[51] Relationship care encourages medical professionals to empathize with the patient. Relationship-centered care focuses more on empathizing with the patient due to their ability to Express their emotion.[52] When the patient expresses their emotion, it helps both ways in terms of the health professional understanding the patient and serving the patient's needs.[52] In the cognitive domain, medical professionals concentrate on the idea of the relationship center and emphasize providing medical information as well as patient education. Care involves mutual trust, respect, and acceptance in the emotional domain.[53]

Applications

[edit]Health communication has become essential in promoting the general public health in myriad situations. One of health communication's most important applications has been throughout major Environmental events (e.g. hurricanes, flooding, tornados) and addressing the affected audience's questions and needs quickly and efficiently, keeping the protection of public health and the forefront of their message.[2] Health communication professionals are constantly working to improve this type of risk communication in order to be prepared in the case of an emergency.

Another increasingly important application of health communication has been in reaching students in the college community. The National College Health Assessment has measured that 92.5% of college students reported being in "good, very good, or excellent health", however college students seem to battle serious problems with stress, depression, substance abuse, and a general lack of nutrition in comparison to other age groups and audiences.[54] Professionals in health communication are actively striving for new ways to reach this at-risk audience in order to raise standards of public health in the college setting and to promote a healthier life style amongst students.

Challenges

[edit]There are many challenges in communicating information about health to individuals. Some of the most essential issues have to do with the gap between individual health literacy and healthcare workers and institutions, as well as flaws in communicating health information through mass media.

Health communication is additionally influenced by cultural values which in some cases can create a barrier in effective health communication. When the sender and receiver are from contrasting socioeconomic backgrounds, of a different race, or even vastly different ages, effective health communication declines. This is a result of the fact that people tend to trust and be more open to ideas coming from someone similar to themselves.[55]

Literacy-communication gap

[edit]One problem that health communication seeks to address is the gap that has formed between health literacy and the use of health communication.[56] While the goal is that health communication will effectively lead to health literacy, issues such as the use of unexplained medical jargon, ill-formed messages, and often a general educational gap have created barriers to patient healthcare literacy. Specifically, studies have been done amongst elderly populations in America to illustrate a common audience who is left at a disadvantage due to this issue.[57] The older adults comprise an age group that generally has the most chronic health conditions in comparison to other age groups, however studies have shown[citation needed] that this group has difficulty understanding written health materials, understanding health care and policies, and generally do not comprehend medical jargon. Such shortcomings of health communication may lead to increased hospitalizations, the inability to respond to and manage a disease or medical condition, and a generally declining health status.[citation needed]

To redress these problems, health communication professionals have recommended programs for improving physician communication with patients. One recommendation is to improve medical student training by adding lectures, workshops, and supervised encounters with patients to teach interpersonal and communication skills as a core competency.[58] It is also recommended that practicing physicians improve their communication skills by attending webinars and on-site customized training programs. If physicians can improve their communication skills, they can ameliorate the problem of patient healthcare illiteracy and contribute to better patient adherence to medical advice.

In some populations, health-related websites (e.g., WebMD) and online support groups (e.g., Association for Cancer Online Resources) have increased access to health information.[6] The role of language in communication, especially related to the patients' preferred language physicians use to communicate with them in, also plays a role. Results of a 2019 systematic review found that limited English proficient (LEP) patients have improved health outcomes when they receive care from physicians fluent in the patients' own preferred language.[59] The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) has published review of research for providers of health information, on what happens when health information is not clear, how to help people understand health information, and which groups of the population may need extra support understanding health content.[60] It covers research on using simple, balanced language, finding the correct focus, alternative formats (e.g. videos, visuals), and online information.

Mass media

[edit]Mass communication is used to promote beneficial changes in behavior among members of populations.[61] A major criticism of the use of mass media as a method of health communication is the unfortunate ability for false and misinformed messages to spread quickly through the mass media, before they have the chance to be disputed by professionals. This issue may generate unwarranted panic amongst those who receive the messages and be an issue as technology continues to advance. An example of this may be observed in the ongoing distrust of vaccinations due to the publication of numerous messages that wrongly link the childhood measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccination with the development and onset of Autism.[62] The speed with which this message spread due to new social networking technologies caused many parents to distrust vaccinations and therefore forgo having their children receive the vaccine. Although this panic is based on false information, many still harbor a lingering suspicion towards vaccinations and refuse them, which has caused a public health concern.

Psychological Reactance

[edit]Another challenge of health communication is that it fails sometimes[63] and one of the reason is attributed to psychological reactance, Brehm (1966).[64] It is a theory that posits that people are motivated to reject advocacy messages because such messages are likely to threaten their freedom to make decisions autonomously. Sometimes reactance leads to a boomerang effect that produces the direct opposite behavior in people, especially for health messages which are often persuasive and directive, they easily may appear to limit a person's choice.[65] Reactance theory has been used to understand how health messages covering topics such as binge drinking, smoking, drug use, and fitness elicit reactance rather than compliance.

To reduce resistance to health messages, researchers propose the use of narratives instead of explanatory or fear-inducing messages because of its unique nature to create identification with characters and transport the audience along a story arc. Narrative advertising tends to generate more positive thoughts and feelings about the advertised product or brand compared to traditional argument or advocacy advertising which is the popular message design for health communication.[66]

Historical timeline

[edit]The following are some key events in the development of health communication as a formal discipline since the 1970s.[67]

- International Communication Association establishes the Therapeutic Communication Interest Group (which later became the "Health Communication" Division)

- The American Academy on Physician and Patient (later renamed the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare) was established to promote research, education, and professional standards in patient-clinician communication.

- Health communication textbooks begin appearing: Kreps & Thornton (1984), Sharf (1984), and Northhouse & Northhouse (1985)

- National Communication Association forms the Commission for Health Communication, which later became the Health Communication Division

- First peer reviewed journal devoted to health communication, Health Communication. Followed in 1996 by the Journal of Health Communication

- Undergraduate and graduate health communication majors begin to be offered. Tufts University School of Medicine offers the first Master of Science in health communication together with Emerson College

- The Health Communication Working Group of the American Public Health Association was established to examine the role of health communication in public health promotion.

- The National Cancer Institute (National Institutes of Health) establishes the Health Communication and Informatics Research Branch (HCIRB) in their Behavioral Research Program, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. The National Cancer Institute identifies health communication as an extraordinay research opportunity for promoting cancer prevention and control.

- The National Cancer Institute establishes the Health Communication Intervention research program, funding seven multi-year research projects to study innovative strategies for communicating cancer information to diverse populations.

- The Journal of Medical Internet Research is established to study health and health care in the Internet age.

- The National Cancer Institute establishes the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) biennial representative national survey of consumer health information seeking, acquisition, and use to evaluate progress in cancer communication and to guide health communication intervention.

- The National Cancer Institute announced establishment of four national Centers of Excellent in Cancer Communication Research (CECCRs) providing five year funding for research centers at the University of Pennsylvania, University of Wisconsin, University of Michigan, and Saint Louis University. The CECCR program was designed to make major advances in health communication research and application, as well as to train the next generation of health communication scholars.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) establishes the National Center for Health Marketing (NCHM)for promoting and conducting health marketing and communication research to support national health promotion efforts.

- The Coalition for Health Communication (CHC) is established as an inter-organizational task force whose mission is to strengthen the identity and advance the field of health communication. CHC represents the ICA and NCA Health Communication Divisions and the APHA Health Communication Working Group.

- The first dedicated Ph.D. program in Health and Strategic Communication is offered by the George Mason University Department of Communication.

- The National Cancer Institute announced re-issuing of the national Centers of Excellent in Cancer Communication Research (CECCRs) program. They provided five years of funding for five research centers (at the University of Pennsylvania, University of Wisconsin, University of Michigan, Washington University in St. Louis, and Kaiser Permanente, Colorado. The new CECCR program was designed to continue progress in advancing in health communication research and application, as well as to train the next generation of health communication scholars.

- First serious efforts put forth by Home Controls' HealthComm Systems to educate consumers regarding affordable, unobtrusive home technology allowing the aging to remain at home for months or years longer than ever before

- The Society for Participatory Medicine (SPM) is established to promote participatory medicine by and among patients, caregivers and their medical teams and to promote clinical transparency among patients and their physicians through the exchange of information, via conferences, as well through the distribution of correspondence and other written materials. The SPM publishes the Journal of Participatory Medicine.

- The Murrow Center for Media and Health Promotion is established at Washington State University.

- The Center for Health Communication is established in the Moody College of Communication at the University of Texas at Austin.

- The Public Health Film Society (PHFS), an independent charity is established to promote conversations between the health and artistic communities about public health messages in film, and to promote transparency in the portray of health messages to the general public through film festivals, international film competitions, as well through the distribution of correspondence and peer-reviewed research.[41][44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "What is Communication?". National Communication Association. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Beato, Ricardo R.; Jana Telfer (July–August 2010). "Communication as an Essential Component of Environmental Health Science" (PDF). Journal of Environmental Health. 73 (1): 24–25. PMID 20687329. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "Health Communication Basics". Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Egelhofer, Marc (September 2007). "Health Communication: From Theory to Practice. By Renata Schiavo". Biotechnology Journal. 2 (9): 1186. doi:10.1002/biot.200790098. ISSN 1860-6768.

- ^ Gwyn, Richard (2002). Communicating health and illness. London: Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0761964759.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Freimuth, Vicki S.; Sandra Crouse Quinn (December 2004). "The Contributions of Health Communication to Eliminating Health Disparities". American Journal of Public Health. 94 (12): 2053–2055. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.12.2053. PMC 1448587. PMID 15569949.

- ^ Dutta-Bergman, Mohan J. (2005). "The Relation Between Health-Orientation, Provider-Patient Communication, and Satisfaction: An Individual-Difference Approach". Health Communication. 18 (3): 291–303. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc1803_6. ISSN 1041-0236. PMID 16187933. S2CID 23884129.

- ^ Fox, Stephanie; Gaboury, Isabelle; Chiocchio, François; Vachon, Brigitte (2021-01-28). "Communication and Interprofessional Collaboration in Primary Care: From Ideal to Reality in Practice". Health Communication. 36 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1080/10410236.2019.1666499. ISSN 1041-0236. PMID 31580162. S2CID 203653041.

- ^ Thompson, Teresa (1999). "Chapter 1". In Whaley, Bryan B. (ed.). The nature and language of illness explanations (1. ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. pp. 3–40. doi:10.4324/9781410601056. ISBN 9781410601056.

- ^ a b Munodawafa, D. (2008-06-01). "Communication: concepts, practice and challenges". Health Education Research. 23 (3): 369–370. doi:10.1093/her/cyn024. ISSN 0268-1153.

- ^ Dlima, Schenelle (2021-01-29). "The History of Health Communication". Saathealth Spotlight. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ Helen Neal (1962). Better Communications for Better Health. Internet Archive. The National Health Council.

- ^ USPHS. (1963). Surgeon General's Conference on Health Communications November 5–8, 1962. PHS publication, 5-8.

- ^ a b c d e Atkin, Charles; Silk, Kami (2014). "Health Communication". In Stacks, Don W.; Salwen, Michael B. (eds.). An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research. Communication Theory and Methodology (Second ed.). Routledge. pp. 489–503. doi:10.4324/9780203887011. ISBN 978-0-8058-6381-9.

- ^ "Home - Wits University". www.wits.ac.za. Retrieved 2023-04-20.

- ^ Grossbach, Irene; Stranberg, Sarah; Chlan, Linda (2011-06-01). "Promoting Effective Communication for Patients Receiving Mechanical Ventilation". Critical Care Nurse. 31 (3): 46–60. doi:10.4037/ccn2010728. ISSN 0279-5442. PMID 20807893.

- ^ a b Edgar, Timothy; James N. Hyde (November 2004). "An Alumni-Based Evaluation of Graduate Training in Health Communication: Results of a Survey on Careers, Salaries, Competencies, and Emerging Trends". Journal of Health Communication. 10 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1080/10810730590904553. PMID 15764441. S2CID 11085610.

- ^ "Graduate Programs in Health Communication". Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ^ "Teaching - EACH". EACH. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ a b Parvis, Leo (Jul–Aug 2002). "How to Benefit From Health Communication". Journal of Environmental Health. 65 (1): 41. PMID 12148326.

- ^ Schiavo, Renata (2021-10-02). "Telling our own stories: The role of narrative in confronting stigma and misinformation". Journal of Communication in Healthcare. 14 (4): 269–270. doi:10.1080/17538068.2021.2002592. ISSN 1753-8068. S2CID 244775363.

- ^ Schiavo, Renata; Eyal, Gil; Obregon, Rafael; Quinn, Sandra C.; Riess, Helen; Boston-Fisher, Nikita (2022-10-10). "The science of trust: future directions, research gaps, and implications for health and risk communication". Journal of Communication in Healthcare. 15 (4): 245–259. doi:10.1080/17538068.2022.2121199. ISSN 1753-8068. PMID 36911900. S2CID 252838082.

- ^ Schiavo, Renata; Wye, Gretchen Van; Manoncourt, Erma (2022-01-02). "COVID-19 and health inequities: the case for embracing complexity and investing in equity- and community-driven approaches to communication". Journal of Communication in Healthcare. 15 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/17538068.2022.2037349. ISSN 1753-8068. S2CID 247453892.

- ^ a b ""Doing" Critical Health Communication. A Forum on Methods". Frontiers Research Topic. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ^ Zoller, Heather M.; Kline, Kimberly N. (January 2008). "Theoretical Contributions of Interpretive and Critical Research in Health Communication". Annals of the International Communication Association. 32 (1): 89–135. doi:10.1080/23808985.2008.11679076. ISSN 2380-8985. S2CID 148377352.

- ^ Noar, Seth M.; Christina N. Benac; Melissa S. Harris (2007). "Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions". Psychological Bulletin. 133 (4): 673–693. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.673. PMID 17592961. S2CID 21694712.

- ^ a b Snyder, Leslie B. (2007). "Health Communication Campaigns and Their Impact on Behavior". Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 39 (2): S32–S40. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2006.09.004. ISSN 1499-4046. PMID 17336803.

- ^ a b Beaudoin, Christopher E.; Fernandez, Carolyn; Wall, Jerry L.; Farley, Thomas A. (2007). "Promoting Healthy Eating and Physical Activity". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 32 (3): 217–223. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2006.11.002. ISSN 0749-3797. PMID 17236742.

- ^ Gostin, Lawrence O.; Klock, Kevin A.; Ginsbach, Katherine F.; Halabi, Sam F.; Hall-Debnam, Taylor; Lewis, Janelle; Perlman, Vanessa S.; Robinson, Katie (2023-05-09). "Advancing Equity In The Pandemic Treaty". Health Affairs. doi:10.1377/forefront.20230504.241626.

- ^ "More than 300,000 people reached with awareness-raising campaign to contain deadly Ebola outbreak in DRC". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 2023-04-08.

- ^ "What Is China's 'Zero-COVID' Policy?". VOA. 28 November 2022. Retrieved 2023-04-08.

- ^ "Heatwaves and Health". www.paho.org. Retrieved 2023-04-08.

- ^ a b c d Finset, Arnstein; Bosworth, Hayden; Butow, Phyllis; Gulbrandsen, Pål; Hulsman, Robert L.; Pieterse, Arwen H.; Street, Richard; Tschoetschel, Robin; van Weert, Julia (2020-05-01). "Effective health communication – a key factor in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic". Patient Education and Counseling. 103 (5): 873–876. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.027. ISSN 0738-3991. PMC 7180027. PMID 32336348.

- ^ a b c Motta, Matt; Sylvester, Steven; Callaghan, Timothy; Lunz-Trujillo, Kristin (2021-01-28). "Encouraging COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake Through Effective Health Communication". Frontiers in Political Science. 3. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.630133. ISSN 2673-3145.

- ^ a b Goldstein, Susan; MacDonald, Noni E.; Guirguis, Sherine (August 2015). "Health communication and vaccine hesitancy". Vaccine. 33 (34): 4212–4214. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.042.

- ^ a b Hornik, Robert, ed. (2002-01-01). "Public Health Communication". Behavioral Sciences, Communication Studies. doi:10.4324/9781410603029. ISBN 9781410603029.

- ^ a b c d Niederdeppe, Jeff; Kuang, Xiaodong; Crock, Brittney; Skelton, Ashley (2008). "Media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations: What do we know, what do we need to learn, and what should we do now?". Social Science & Medicine. 67 (9): 1343–1355. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.037. ISSN 0277-9536. PMID 18691793.

- ^ a b "When Cotton Mather Fought The Smallpox". www.americanheritage.com. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ^ Best, M (2004-02-01). ""Cotton Mather, you dog, dam you! I'l inoculate you with this; with a pox to you": smallpox inoculation, Boston, 1721". Quality and Safety in Health Care. 13 (1): 82–83. doi:10.1136/qshc.2003.008797. ISSN 1475-3898. PMC 1758062. PMID 14757807.

- ^ a b Friedman, Allison L.; Kachur, Rachel E.; Noar, Seth M.; McFarlane, Mary (February 2016). "Health Communication and Social Marketing Campaigns for Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevention and Control: What Is the Evidence of their Effectiveness?". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 43 (2S): S83–S101. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000286. ISSN 0148-5717. PMID 26779691.

- ^ a b Botchway, Stella; Hoang, Uy (2016). "Reflections on the United Kingdom's first public health film festival". Perspectives in Public Health. 136 (1): 23–24. doi:10.1177/1757913915619120. PMID 26702114. S2CID 21969020.

- ^ "The APHA Global Public Health Film Festival".

- ^ "Global Health Film | Home".

- ^ a b Hoang, U.; Luna, P.; Russell, P.; Bergonzi-King, L.; Ashton, J.; McCarthy, C.; Donovan, H.; Inman, P.; Seminog, O.; Botchway, S. (2018). "First International Public Health Film Competition 2016—reflections on the development and use of competition judging criteria". Journal of Public Health. 40: 169–174. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdx022. PMID 28369436. S2CID 4055604.

- ^ Apker, Julie (2011). Communication in health organizations (1 ed.). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-745-64754-8.

- ^ Naughton, Cynthia (2018-02-13). "Patient-Centered Communication". Pharmacy. 6 (1): 18. doi:10.3390/pharmacy6010018. ISSN 2226-4787. PMC 5874557. PMID 29438295.

- ^ Frezza, Eldo E. (2019-08-22), "Patient-Centered Care", Patient-Centered Healthcare, Boca Raton : Routledge/Taylor & Francis, 2020.: Productivity Press, pp. 3–9, doi:10.4324/9780429032226-1 (inactive 13 December 2024), ISBN 978-0-429-03222-6, S2CID 208405231, retrieved 2023-12-14

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of December 2024 (link) CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Naughton, Cynthia (2018-02-13). "Patient-Centered Communication". Pharmacy. 6 (1): 18. doi:10.3390/pharmacy6010018. ISSN 2226-4787. PMC 5874557. PMID 29438295.

- ^ a b c Plug, Ilona; van Dulmen, Sandra; Stommel, Wyke; olde Hartman, Tim C.; Das, Enny (2022). "Physicians' and Patients' Interruptions in Clinical Practice: A Quantitative Analysis". The Annals of Family Medicine. 20 (5): 423–429. doi:10.1370/afm.2846. ISSN 1544-1709. PMC 9512556. PMID 36228066.

- ^ Hashim, M. Jawad (2017-01-01). "Patient-Centered Communication: Basic Skills". American Family Physician. 95 (1): 29–34. PMID 28075109.

- ^ a b Nundy, Shantanu; Oswald, John (2014). "Relationship-centered care: A new paradigm for population health management". Healthcare. 2 (4): 216–219. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.09.003. ISSN 2213-0764. PMID 26250627.

- ^ a b Beach, Mary Catherine; Inui, Thomas (2006). "Relationship-centered Care. A Constructive Reframing". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 21 (S1): S3–S8. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC 1484841. PMID 16405707.

- ^ Kelley, John M.; Kraft-Todd, Gordon; Schapira, Lidia; Kossowsky, Joe; Riess, Helen (2014-04-09). Timmer, Antje (ed.). "The Influence of the Patient-Clinician Relationship on Healthcare Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e94207. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...994207K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0094207. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3981763. PMID 24718585.

- ^ Baxter, Leslie; Nichole Egbert; Evelyn Ho (Jan–Feb 2008). "Everyday Health Communication Experiences of College Students". Journal of American College Health. 56 (4): 427–435. doi:10.3200/jach.56.44.427-436. PMID 18316288. S2CID 19254752.

- ^ Kreuter, Matthew W.; McClure, Stephanie M. (2004-04-01). "The Role of Culture in Health Communication". Annual Review of Public Health. 25 (1): 439–455. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000. ISSN 0163-7525. PMID 15015929.

- ^ Viswanath K, Finnegan JR (1996). ".". In Burleson, B (ed.). Communication Yearbook 19. SAGE Publications. pp. 187–227.

- ^ Hester, Eva Jackson (February 2009). "An Investigation of the Relationship Between Health Literacy and Social Communication Skills in Older Adults". Communication Disorders Quarterly. 30 (2): 112–119. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.666.701. doi:10.1177/1525740108324040. S2CID 143464629.

- ^ Christianson JB (2012). Physician Communication with Patients: Research Findings and Challenges. University of Michigan Press. pp. 222–238.

- ^ Diamond, Lisa; Izquierdo, Karen; Canfield, Dana; Matsoukas, Konstantina; Gany, Francesca (2019). "A Systematic Review of the Impact of Patient–Physician Non-English Language Concordance on Quality of Care and Outcomes". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 34 (8): 1591–1606. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04847-5. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC 6667611. PMID 31147980.

- ^ "Health information: are you getting your message across?". NIHR Evidence. 13 June 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_51109. S2CID 249946766.

- ^ Abroms, LC; Maibach, EW (2008). "The effectiveness of mass communication to change public behavior". Annual Review of Public Health. 29: 219–34. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090824. PMID 18173391.

- ^ Brauser, Deborah (January 6, 2001). "Autism and MMR Vaccine Study an 'Elaborate Fraud,' Charger BMJ".

- ^ Freimuth, V. S. (1990). The chronically uninformed: Closing the knowledge gap in health. In E. B. Ray & L. Donohew (Eds.), Communication and health: Systems and applications. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. pp. 171–186.

- ^ Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press.

- ^ Bessarabova, Elena; Fink, Edward L.; Turner, Monique (July 2013). "Reactance, Restoration, and Cognitive Structure: Comparative Statics: Reactance, Restoration, and Cognitive Structure". Human Communication Research. 39 (3): 339–364. doi:10.1111/hcre.12007.

- ^ Bachman, Audrey Smith; Cohen, Elisia L.; Collins, Tom; Hatcher, Jennifer; Crosby, Richard; Vanderpool, Robin C. (2018-10-03). "Identifying Communication Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening Adherence among Appalachian Kentuckians". Health Communication. 33 (10): 1284–1292. doi:10.1080/10410236.2017.1351274. ISSN 1041-0236. PMC 5817037. PMID 28820641.

- ^ Kreps et al. 1998

Sources

[edit]- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2010. Volumes 1 and 2, Chapt. 11, p 11–20. https://web.archive.org/web/20100122053253/http://www.healthypeople.gov/document/HTML/Volume1/11HealthCom.htm.

- Cline R., American Public Health Association (APHA) Health Communication Working Group Brochure, 2003. https://web.archive.org/web/20190119083227/http://www.healthcommunication.net/APHA/APHA.html. Retrieved in January 2010.

- Schiavo, R. Health Communication: From Theory to Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007.

- Thompson, Teresa; Roxanne Parrott; Jon Nussbaum (2011). The Routledge Handbook of Health Communication (2 ed.). ISBN 978-0-203-84606-3. Archived from the original on 2015-05-11. Retrieved 2012-09-21.

- Kreps, G. L.; et al. (1998). "The History and Developments of the Field of Health Communication". Health communication research : a guide to developments and directions. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. doi:10.1145/1125451.1125549.

- Rimal, R. N.; Lapinski (2009). Why Health Communication is Important in Public Health. PMC 2672574. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009.

- Maibach, E. W. (2008). Communication for Health.

- Ringo Ma. (Ed.) (2009). Jiankang chuanbo yu gonggong weisheng [Health communication and public health]. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Educational. (in Chinese and English)

- Ringo Ma. (Ed.) (2009). Yi bing goutong zhi duoshao [How much do you know about doctor-patient communication?]. Hong Kong: KAI Education. (in Chinese and English)

- Teresa L. Thompson; Alicia Dorsey; Roxanne Parrott; Katherine Miller (1 April 2003). The Handbook of Health Communication. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc. ISBN 978-1-4106-0768-3. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- Finney Rutten, Lila J., Kelly D. Blake, Alexandra J. Greenberg-Worisek, Summer V. Allen, Richard P. Moser, and Bradford W. Hesse. "Online health information seeking among US adults: measuring progress toward a healthy people 2020 objective." Public Health Reports 134, no. 6 (2019): 617-625.[1]

- Baniya, S. (2022). Transnational assemblages in disaster response: Networked communities, technologies, and coalitional actions during global disasters. Technical Communication Quarterly, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2022.2034973 [2]

External links

[edit]- American Public Health Association Health Communication Working Group

- The Annenberg Public Policy Center, Health Communication

- Applied Research on Communication in Health Group, University of Otago, Wellington

- Center for Communication and Health, Northwestern University Archived 2016-04-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Center for Excellence in Health Communication to Underserved Populations, The University of Kansas William Allen White School of Journalism and Mass Communications Archived 2015-09-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Center for Health Communication, Moody College of Communication, The University of Texas at Austin

- Center for Health Communication, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

- Center for Health Communication Intervention

- Center for Health Communications Research, University of Michigan

- Center for Health Literacy, MAXIMUS

- The Center for Health & Risk Communication, George Mason University Archived 2011-09-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Center for Health and Risk Communication, University of Maryland

- Center for Public Health Readiness and Communication, Drexel University School of Public Health

- Coalition for Healthcare Communication

- Ebola Communication Network

- FHI 360 Center for Global Health Communication and Marketing

- Centre for Health Communication and Participation, La Trobe University

- Gateway to Health Communication & Social Marketing Practice, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Health Communication Partnership

- Health Communication Research Centre, Cardiff School of English, Communication & Philosophy

- Health and Science Communications Association

- Health Communication Research Center, The Missouri School of Journalism

- Health information: are you getting your message across?

- International Communication Association, Health Communication Section

- Institute for Healthcare Communication

- International Communication Association

- Johns Hopkins University Center for Communication Programs

- Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Health Communication Activities

- University of Georgia Center for Health and Risk Communications Archived 2017-11-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Graduate Program in Health Communication, Tufts University School of Medicine

- Journal of Health Communication Archived 2013-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Public Health Film Society

- ^ Finney Rutten, Lila J.; Blake, Kelly D.; Greenberg-Worisek, Alexandra J.; Allen, Summer V.; Moser, Richard P.; Hesse, Bradford W. (2019-09-12). "Online Health Information Seeking Among US Adults: Measuring Progress Toward a Healthy People 2020 Objective". Public Health Reports. 134 (6): 617–625. doi:10.1177/0033354919874074. ISSN 0033-3549. PMC 6832079. PMID 31513756.

- ^ Baniya, Sweta (2022-10-02). "Transnational Assemblages in Disaster Response: Networked Communities, Technologies, and Coalitional Actions During Global Disasters". Technical Communication Quarterly. 31 (4): 326–342. doi:10.1080/10572252.2022.2034973. hdl:10919/111415. ISSN 1057-2252. S2CID 246437728.