Myth of the clean Wehrmacht

The myth of the clean Wehrmacht (German: Mythos der sauberen Wehrmacht) is the negationist notion that the regular German armed forces (the Wehrmacht) were not involved in the Holocaust or other war crimes during World War II. The myth, heavily promoted by German authors and military personnel after World War II,[2] completely denies the culpability of the German military command in the planning and perpetration of war crimes. Even where the perpetration of war crimes and the waging of an extermination campaign, particularly in the Soviet Union – the populace of which was viewed by the Nazis as "sub-humans" ruled by "Jewish Bolshevik" conspirators – has been acknowledged, they are ascribed to the "Party soldiers corps", the Schutzstaffel (SS), but not the regular German military.

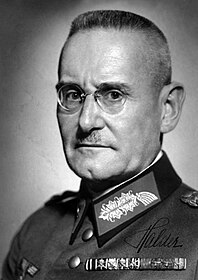

The myth began during the war, being promoted in the Wehrmacht's official propaganda and by soldiers of all ranks seeking to portray their institution in the best possible light; as prospects for victory faded, these soldiers began to portray themselves as victims.[3] After Germany's defeat, the verdict of the International Military Tribunal (1945–1946), which released many of the accused, was misrepresented as exonerating the Wehrmacht. Franz Halder and other Wehrmacht leaders signed the Generals' memorandum entitled "The German Army from 1920 to 1945", which laid out the key elements of the myth, attempting to exculpate the Wehrmacht from war crimes.

The victorious Western Allies were becoming increasingly concerned with the growing Cold War against their former ally, the Soviet Union, and wanted West Germany to begin rearming to counter the perceived Soviet threat. In 1950, West German chancellor Konrad Adenauer and former officers met secretly at Himmerod Abbey to discuss West Germany's rearmament and agreed upon the Himmerod memorandum. This memorandum laid out the conditions under which West Germany would rearm: their war criminals must be released, the "defamation" of the German soldier must cease and foreign public opinion of the Wehrmacht must be raised. The Supreme Commander of NATO, U.S. General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, having previously stated his belief that the "Wehrmacht and the "Hitler gang" (Nazi Party) were all the same",[4] reversed this position and began to facilitate German rearmament in light of his deep concern over Soviet dominance of Eastern Europe. The British became reluctant to pursue further trials and released already-convicted criminals early.

As Adenauer courted the votes of veterans and enacted amnesty laws, Halder began working for the U.S. Army Historical Division. His role was to assemble and supervise former Wehrmacht officers to create a multi-volume operational account of the Eastern Front.[5] He oversaw the writings of 700 former German officers and disseminated the myth through this network. Wehrmacht officers and generals produced exculpatory memoirs distorting the historical record. These writings proved enormously popular, especially the memoirs of Heinz Guderian and Erich von Manstein, and further disseminated the myth among a German public eager to cast off the shame of Nazism.

The year 1995 proved to be a turning point in German public consciousness. The Hamburg Institute for Social Research's Wehrmacht exhibition, which showed 1,380 graphic pictures of "ordinary" Wehrmacht troops complicit in war crimes, sparked a long-running public debate and reappraisal of the myth. Hannes Heer wrote that the war crimes had been covered up by scholars and former soldiers. German historian Wolfram Wette called the clean Wehrmacht thesis a "collective perjury". The wartime generation maintained the myth with vigour and determination. They suppressed information and manipulated government policy. After their passing, there was insufficient motive to maintain the deceit in which the Wehrmacht denied having been a full partner in the Nazis' industrialised genocide.

Outline of the myth

[edit]The Wehrmacht was the combined armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945, the Army (Heer), Navy (Kriegsmarine) and Air Force (Luftwaffe) totaling about 18 million men, created on 16 March 1935 with Adolf Hitler's Defence Law introducing conscription.[6] Approximately half of all German male citizens performed military service as conscripts or volunteers.[7][8][9]

The term "clean Wehrmacht" (saubere Wehrmacht) means German soldiers, sailors and airmen had "clean hands"; in other words, it claims they did not have blood on their hands from murdered prisoners of war, Jews, or civilians.[10] The myth asserts that Hitler and the Nazi Party alone designed the war of annihilation and that war crimes were only committed by the SS, the Nazi Party's special armed force.

In reality, the general officers of the Wehrmacht, and many lower ranks down to common soldiers, were willing participants in Hitler's war of annihilation against perceived enemies of Germany. Wehrmacht troops were complicit in or perpetrated numerous war crimes, routinely assisting SS units with tacit approval from officers.[11] In the aftermath of the war, the West German government deliberately sought to suppress information of such crimes to absolve former war criminals and allow their reintegration into German society.[12]

Background

[edit]

War of extermination

[edit]During World War II the government of Nazi Germany, the Armed Forces High Command (OKW) and the Army High Command (OKH) jointly laid the foundations for genocide in the Soviet Union.[13] From the outset, the war against the Soviet Union was designed as a war of annihilation.[14] The racial policy of Nazi Germany viewed the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe as populated by non-Aryan "sub-humans", ruled by "Jewish Bolshevik" conspirators.[15] It was stated Nazi policy to murder, deport, or enslave the majority of Russian and other Slavic populations according to the Master Plan for the East.[15]

Before and during Operation Barbarossa, the German offensive into the Soviet Union, German troops were repeatedly subjected to anti-Bolshevik, antisemitic, and anti-Slavic indoctrination.[16] Following the invasion, Wehrmacht officers described the Soviets to their soldiers as "Jewish Bolshevik sub-humans", the "Mongol hordes", the "Asiatic flood" and the "Red beast",[17] and many German troops accepted this racialist ideology.[18] In a speech to the 4th Panzer Group, General Erich Hoepner echoed the Nazi racial plans by claiming the war against the Soviet Union was "an essential part of the German people's struggle for existence", and that "the struggle must aim at the annihilation of today's Russia and must therefore be waged with unparalleled harshness".[19]

The murder of Jews was common knowledge in the Wehrmacht. During the retreat from the Soviet Union, German officers destroyed incriminating documents.[20] Wehrmacht soldiers actively worked together with the Schutzstaffel (SS) paramilitary death squads, the Einsatzgruppen, and participated in the mass killings such as at Babi Yar.[21] Wehrmacht officers considered the relationship with the Einsatzgruppen to be very close and almost cordial.[22]

Crimes in Greece, Poland, the Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia

[edit]

The Wehrmacht carried out war crimes across the continent including in Poland, Greece, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union.[23] The first significant combat for the Wehrmacht was the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939. In April 1939 Reinhard Heydrich, the architect of the Final Solution, had already arranged co-operation between the intelligence sections of the Wehrmacht and the Einsatzgruppen.[24] The Wehrmacht's participation in the large-scale killings of civilians and partisans in Poland was a prelude to the war of annihilation in Russia.[25] On the first day of the invasion, Polish prisoners of war were murdered by the Wehrmacht at Pilchowice, Czuchów, Gierałtowice, Bojków, Lubliniec, Kochcice, Zawiść, Ornontowice, and Wyry.[26]: 11 During the invasion, the Wehrmacht is estimated to have executed between 16,000 to 27,000 Poles[27]: 16 , including at least 3,000 Polish POWs.[28]: 121 [29]: 241

Soviet Belarus has been described as "the deadliest place on earth between 1941 and 1944".[30] One in three Belarusians died during the war. Most Soviet Jews lived in an area of Western Russia previously known as the Pale of Settlement.[31] In this area, the Holocaust was carried out near populous towns rather than in extermination centres like Auschwitz.[32] The Wehrmacht was initially tasked with assisting the Einsatzgruppen in their task of complete extermination of the Jewish population. In the town of Krupki, the army marched the Jewish population of approximately 1,000 a mile out of the town to meet their SS executioners. The frail and sick were conveyed by truck, and those who strayed were shot and killed immediately. German troops guarded the site, and alongside the SS, shot the Jews at the edge of a pit. Krupki was typical: the Wehrmacht was a full partner in systematic mass murder.[33]

German military brothels were set up throughout much of occupied Europe.[34] In many cases in Eastern Europe, women and teenage girls were kidnapped from the streets during German military and police round-ups to be used as sex slaves.[35][36][37] The women were raped by up to 32 men per day at a nominal cost of three Reichsmarks.[37] A Swiss Red Cross mission driver Franz Mawick wrote about what he saw in 1942:

Uniformed Germans ... gaze fixedly at women and girls between the ages of 15 and 35. One of the soldiers pulls out a pocket flashlight and shines it on one of the women, straight into her eyes. The two women turn their pale faces to us, expressing weariness and resignation. The first one is about 40 years old. 'What is this old whore looking for around here?' – one of the three soldiers laughs. 'Bread, sir' – asks the woman ... 'A kick in the ass you get, not bread' – answers the soldier. The owner of the flashlight directs the light again on the faces and bodies of girls ... The youngest is maybe 13 years old ... They open her coat and start groping her. 'This one is ideal for bed' – he says.[37]

According to a study by Alex J. Kay and David Stahel, the majority of Wehrmacht soldiers deployed to the Soviet Union participated in war crimes.[38]

Yugoslavia and Greece were jointly occupied by the Italians and Germans. The Germans began persecuting the Jews immediately, but the Italians refused to co-operate. Wehrmacht officers tried to pressure their Italian counterparts to stop the exodus of Jews from German-occupied areas; however, the Italians refused. General Alexander Löhr reacted with disgust, describing the Italians as weak.[39] He wrote an angry communique to Hitler saying the "implementation of the Croatian government's laws concerning Jews is being so undermined by Italian officials that in the coastal zone – particularly in Mostar, Dubrovnik, and Crikvenika – numerous Jews are protected by the Italian military, and other Jews have been escorted across the border to Italian Dalmatia and Italy itself".[40]

In Serbia, the Wehrmacht began the murder of the Jews from mid-1941, independently of the SS.[41] In April 1941 in the early days of the occupation, Chief of Military Administration Harald Turner decreed the registration of Jews, including forced labor and curfews. This culminated in the Geiselmordpolitik, the reprisal killings by the Wehrmacht for insurgency and sabotage.[42] In September 1942, the Wehrmacht was also involved in a massacre of civilians in Samarica, where they reportedly killed 480 "enemy combatants" with a loss of one German soldier. At the same time the Wehrmacht condemned similar actions taken by the fascist Ustasa party of the Independent State of Croatia.[43]

Start of the myth

[edit]The Generals' memorandum

[edit]General Franz Halder, Chief of Staff of the OKH between 1938 and 1942, played a key role in creating the myth of the clean Wehrmacht.[44] The genesis for the myth was the "Generals' Memorandum" created in November 1945 and submitted to the Nuremberg trials. It was titled "The German Army from 1920 to 1945" and was co-authored by Halder and former field marshals Walther von Brauchitsch and Erich von Manstein, along with other senior military figures. It portrayed the German armed forces as apolitical and largely innocent of the crimes committed by the Nazi regime.[45][46] The arguments of the memorandum were later adopted by Hans Laternser, the lead counsel for the defence of senior Wehrmacht commanders at the High Command Trial.[45] The document was written at the suggestion of American general William J. Donovan of the OSS, who viewed the Soviet Union as the main global threat to world peace. Donovan served as a deputy prosecutor at Nuremberg; he and some other U.S. representatives believed the trials should not proceed, but that Germany should be recruited as a military ally against the Soviet Union in the growing Cold War.[46]

The Hankey lobby

[edit]In Britain, Paymaster General Maurice Hankey had been one of Britain's most established civil servants, holding a series of powerful posts from 1908 to 1942 and giving strategy advice to every prime minister from H.H. Asquith to Winston Churchill.[47] Hankey deplored the war crimes trials as an injustice to soldiers who had fought honourably, and also a blunder since Britain might need former Wehrmacht generals to fight against the Soviet Union in a possible Third World War.[47] Though little known to the public, Hankey led a powerful lobbying group in Britain on behalf of the Wehrmacht generals[48] as well as Japanese war criminals.[49] He regularly corresponded with Winston Churchill, Anthony Eden, Douglas MacArthur, and Konrad Adenauer about the issue,[50] and personally conferred with Adenauer during a London visit in 1951.[50] When the leader of the main German veterans group, the VdS, Admiral Gottfried Hansen, visited Britain in 1952 to discuss the Kesselring case, the first person he visited was Hankey.[51]

Members of Hankey's group included Labour MP Richard Stokes, Field Marshal Harold Alexander, Lord De L'Isle, Frank Pakenham, Lord Dudley, Victor Gollancz, Lord Cork Frederic Maugham, lawyer Reginald Paget, historians Basil Liddell Hart and J. F. C. Fuller, and the bishop of Chichester George Bell.[52] As a master of bureaucratic in-fighting with excellent connections among the British Establishment and the media, Hankey was, in the words of German historian Kerstin von Lingen, the leader of the "most powerful" lobby group ever formed on behalf of the Wehrmacht generals.[49] While Hankey was opposed to trying fellow soldiers on principle, some of his followers were outright Nazi apologists, such as military historian J. F. C. Fuller.[48]

In 1950, after Field Marshal Albert Kesselring was convicted by a British military court of ordering the massacres of Italian civilians during 1943–45, including the Ardeatine massacre, Hankey used his influence to have one of Kesselring's interrogators, Colonel Alexander Scotland, publish a letter to The Times calling the verdict into question.[53] Scotland's letter had considerable impact on British public opinion, and led to demands that Kesselring be freed.[54] Hankey and his circle drew a picture of Kesselring as a chivalrous leader unaware of the massacres by his men, who would have stopped them had he known. They argued that an officer as effective and thoroughly professional as Kesselring would not have stooped to war crimes, though Lingen dismisses this.

Himmerod memorandum

[edit]

The Western Allies were concerned with the possibility of war with the Soviet Union and a communist invasion.[55] In 1950, after the start of the Korean War, it became clear to the Americans that a German army would have to be revived against the threat of the Soviet Union.[56] Equally concerned, the British were desperate to convince the West German government to join the European Defence Community and NATO.[57][58]

Konrad Adenauer, the West German chancellor, arranged secret meetings between his officials and former Wehrmacht officers to discuss the rearmament of West Germany. The meetings took place at Himmerod Abbey between 5 and 9 October 1950, and included Hermann Foertsch, Adolf Heusinger, and Hans Speidel. During the war, Foertsch had worked under Walter von Reichenau, an ardent Nazi who issued the Severity Order. Foertsch became one of Adenauer's defence advisors.[59]

The Wehrmacht officers made a number of demands to cooperate in West German rearmament, laid out in the Himmerod memorandum: all German soldiers convicted as war criminals would be released, the "defamation" of the German soldier, including the Waffen-SS, would cease, and "measures to transform both domestic and foreign public opinion" of the German military would need to be taken.[56]

The chairman of the meetings summarised the foreign policy changes demanded in the memorandum as follows: "Western nations must take public measures against the 'prejudicial characterisation' of former German soldiers and must distance the former regular armed forces from the 'war crimes issue'".[60] Adenauer accepted the memorandum and began a series of negotiations with the three Western Allied Forces to satisfy the demands.[56]

In response, U.S. General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, recently appointed as the Supreme Commander of NATO on 19 December 1950, and the future 34th President of the United States, changed his negative rhetoric on the Wehrmacht. In January 1951 during a visit to Germany, he made a public statement that there was "a real difference between the German soldier and Hitler and his criminal group".[61] Chancellor Adenauer made a similar statement in a Bundestag debate on the Article 131 of the Grundgesetz, West Germany's provisional constitution. He stated the German soldier fought honourably, as long as he "had not been guilty of any offence".[59] The declarations by Eisenhower and Adenauer reshaped Western public perception of the German war effort and laid the foundation for the myth of the clean Wehrmacht.[62]

West German public opinion

[edit]In the immediate aftermath of World War II, there was a great deal of German sympathy for their war criminals. The British High Commissioner in occupied Germany felt compelled to remind the German public the criminals involved had been found guilty of participating in the torture or murder of Allied citizens.[63] In the late 1940s and 1950s a flood of polemical books and essays demanded freedom for the "so-called 'war criminals'", whose guilt was thrown into doubt.[63] German historian Norbert Frei wrote that the widespread sympathy for the war criminals was an indirect admission of the whole society's enmeshment in National Socialism. The war crimes trials painfully reminded ordinary Germans of their fervent support for the disastrous Nazi regime, and exculpating the generals allowed them to distance themselves from it.[64] The Wehrmacht was a central founding institution of Germany, tracing its descent back to the Prussian Army of the "Great Elector" Frederich Wilhelm, and its complicity with Hitler presented problems for those who wanted to portray the Nazi era as a "freakish aberration" from the course of German history. So many Germans had served in the Wehrmacht that there was a widespread demand for a version of the past that allowed them to "...honour the memory of their fallen comrades and to find meaning in the hardships and personal sacrifice of their own military service".[65] Wette writes: the founding years of West Germany saw the wartime generation cement over its past and make outraged claims that innocence was the norm.[66]

Growth of the myth

[edit]Political climate

[edit]

In the early 1950s political parties in West Germany took up the cause of the war criminals and entered a virtual competition for the votes of wartime veterans. A wide political consensus existed that represented the view that it was "time to close the chapter".[64] West German chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, initiated policies that included an amnesty, the end to denazification programmes, and an exemption from punishment law. Adenauer courted the votes of veterans by making a highly public visit to the remaining war criminals' jail. This gesture helped him win the federal elections of 1953 with a two-thirds majority.[64] Adenauer successfully limited the responsibility for war crimes to Hitler and a small number of "major war criminals".[67] In the 1950s, criminal investigations into the Wehrmacht were halted and there were no convictions. The German ministers of justice had enacted a war crimes law, which in practice was awkwardly defined. Adalbert Rückerl, the investigative chief, interpreted the law as meaning only the SS, the security police, concentration camp guards, ghettos and forced labour criminals could be investigated. The myth was firmly established in the public mind and German prosecutors were unwilling to challenge the prevailing national mood and investigate suspected war criminals in the Wehrmacht.[68] The new German armed forces (the Bundeswehr) was established in 1955 with prominent members of the Wehrmacht in positions of authority. If large numbers of former Wehrmacht officers were indicted on war crimes the Bundeswehr would have been damaged and discredited both in Germany and abroad.[69]

Following the return of the last prisoners of war from Soviet captivity, 600 former members of the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS swore a public oath on 7 October 1955 in the Friedland Barracks, which received a strong media reaction. The oath said: "[W]e swear that we have neither committed murder, nor defiled, nor plundered. If we have brought suffering and misery on other people, it was done according to the Laws of War".[70]

Memoirs and historical studies

[edit]Former German officers published memoirs and historical studies that contributed to the myth. The chief architect of this body of work was Franz Halder. He worked for the Operational History (German) Section of the U.S. Army Historical Division and had exclusive access to the captured German war archives stored in the U.S. He supervised the work of other former German officers and wielded a great deal of influence.[71] Formally Halder's role was to assemble and supervise Wehrmacht officers to write a multi-volume history of the Eastern Front so that U.S. Army officers could obtain military intelligence about the Soviet Union.[72] However, he also formulated and disseminated the myth of the clean Wehrmacht.[72] German historian Wolfram Wette wrote that most Anglo-American military historians have a strong admiration for the "professionalism" of the Wehrmacht, and tended to write about the Wehrmacht in a very admiring tone, largely accepting the version of history set out in the memoirs of former Wehrmacht leaders.[73] Wette suggested this "professional solidarity" had something to do with the fact that for a long time most military historians in the English-speaking world tended to be conservative former Army officers, who had a natural empathy with conservative former Wehrmacht officers, whom they identified as men much like themselves.[73] The picture of highly "professional" Wehrmacht committed to Prussian values that were allegedly inimical to Nazism while displaying super-human courage and endurance against overwhelming odds, especially on the Eastern Front, does appeal to a certain type of historian.[74] Wette described Halder as having a "decisive influence in West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s on the way the history of the Second World War was written".[75]

Various historians across the political spectrum such as Gordon A. Craig, General J. F. C. Fuller, Gerhard Ritter, Friedrich Meinecke, Basil Liddell Hart, and John Wheeler-Bennett all found it inconceivable that the "correct" Wehrmacht officer's corps could have been involved in genocide and war crimes.[76] Claims by Soviet historians that the Wehrmacht had committed war crimes were generally dismissed as "communist propaganda", indeed in the context of the Cold War, the very fact that such claims were being made by the Soviets helped serve more persuasive in the West that the Wehrmacht had behaved honourably.[76] The tendency on the part of many people in the West to see the main theatres of war in Europe as being in Western Europe with the Eastern Front as a side-show further increased the lack of interest in the topic.[76]

After the war Wehrmacht officers and generals produced a slew of memoirs that followed the myth of the clean Wehrmacht.[77] Erich von Manstein and Heinz Guderian produced best-selling memoirs.[78] Guderian's memoirs contained numerous exaggerations, untruths and omissions. He wrote that Russian people greeted German soldiers as liberators and boasted about the personal care he had taken to protect Russian culture and religion.[79] Guderian endeavoured to get German officers released in return for German military support in the defence of Europe. He fought particularly hard for the release of Joachim Peiper, the Waffen-SS commander found guilty of murdering U.S. prisoners of war at the Malmedy massacre. Guderian said that General Thomas Handy, Commander in Chief, U.S. European Command, wanted to hang Peiper and that he would "cable President Truman and ask him if he is familiar with this idiocy".[80]

Erwin Rommel and his memory were used to shape perceptions of the Wehrmacht. Friedrich von Mellenthin's memoirs, Panzer Battles, went through six printings between 1956 and 1976. Mellenthin's memoirs use racist language such as characterising the Russian soldier as an "Asiatic dragged from the deepest recess of the Soviet Union", a "primitive", and "[lacking] any true religious or moral balance, his moods alter between bestial cruelty and genuine kindness".[81] Over a million copies of Hans-Ulrich Rudel's memoirs, Stuka Pilot, were sold. Unusually, he made no secret of his admiration for Hitler.[81] Rudel's memoirs describe dashing adventures, heroic exploits, sentimental comradeship and narrow escapes. One American interrogator described him as a typical Nazi officer. After the war he went to Argentina and started a rescue agency for Nazis called "Eichmann-Runde", that helped Josef Mengele among others.[82]

Historians outside Germany did not study the Holocaust in the 1960s and there were almost no studies of the Wehrmacht's involvement in the Final Solution.[73] Austrian-born American historian Raul Hilberg found that in the 1950s successive publishers rejected his later critically acclaimed book The Destruction of the European Jews. He was told that nobody in America was interested in the topic.[83] Until the 1990s, military historians writing the history of World War II focused on the campaigns and battles of the Wehrmacht, treating the genocidal policies of the Nazi regime in passing.[84] Historians of the Holocaust and the occupation policies of Nazi Germany often did not write about the Wehrmacht at all.[84]

Franz Halder

[edit]

As the Cold War progressed, the military intelligence provided by the German section of U.S. Army Historical Division became increasingly important to the Americans.[5] Halder oversaw the German section of the research programme which became known as the "Halder Group".[85] His group produced over 2,500 major historical manuscripts from over 700 distinct German authors detailing World War II.[86] Halder manipulated the group into reinventing another war-time history from truths, half-truths, distortion, and lies.[44] He set up a "control group" of trusted former Nazi officers who vetted all the manuscripts and required the authors to change the content.[87] Halder's deputy in the group was Adolf Heusinger who was also working for the Gehlen Organisation, a U.S. military intelligence organisation in Germany.[74] Halder expected to be addressed as "General" by the writing teams and behaved as their commanding officer while dealing with their manuscripts.[88] His aim was to exonerate German army personnel from the atrocities they had committed.[89]

Halder laid down a version of history that all the writers had to abide by. This version stated the army was Hitler's victim and had opposed him at every opportunity. The writers had to emphasise the "decent" form of war conducted by the army and blame the SS for the criminal operations.[88] Halder enjoyed a privileged position, as the few historians working on World War II history in the 1950s had to obtain historical information from him and his group. His influence extended to newspaper editors and authors.[90] Halder's instructions were sent down the chain of command and were recorded by former Field Marshal Georg von Küchler. They said: "It is German deeds, seen from the German standpoint, that are to be recorded; this will constitute a memorial to our troops", "no criticism of measures ordered by the leadership" is allowed and no one is to be "incriminated in any way". The achievements of the Wehrmacht were to be emphasised instead.[91] Military historian Bernd Wegner, examining Halder's work, wrote: "The writing of German history on the Second World War, and in particular on the Russian front, was for over two decades, and in part up to the present day – and to a far greater extent than most people realise – the work of the defeated".[92] Wolfram Wette wrote: "In the work of the Historical Division the traces of the War of Annihilation for which the Wehrmacht leadership was responsible were covered up".[90]

In 1949, Halder wrote, Hitler als Feldherr which translates into English as Hitler as Commander and was published in 1950. The work contained the central ideas behind the myth of the clean Wehrmacht that were subsequently reproduced in countless histories and memoirs. The book describes an idealised commander who is then compared to Hitler. The commander is noble, wise, against the war in the East and free from any guilt. Hitler alone was responsible for the evil committed; his complete immorality is contrasted with the moral behaviour of the commander who had done no wrong.[93]

The Americans were aware the manuscripts contained numerous apologia. However, they also contained intelligence the Americans viewed as important in the event of a war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.[89] Halder had coached former Nazi officers on how to make incriminating evidence disappear.[94] Many of the officers he coached such as Heinz Guderian went on to write best-selling autobiographies that broadened the appeal of the apologia.[87] Halder succeeded in his aim of rehabilitating the German officer corps, first with the U.S. military, then widening circles of politics and finally with millions of Americans.[95] Ronald Smelser and Edward J. Davies writing in The Myth of the Eastern Front said: "Franz Halder embodies better than any other high German officer the dramatic difference between myth and reality as it emerged after World War II".[96]

Erich von Manstein

[edit]

Erich von Manstein was a key figure in the creation of the myth of the clean Wehrmacht. His influence was second only to that of Halder.[97] After the war his declared lifetime task was burnishing the memory of the Wehrmacht and "cleaning" it of war crimes.[98] His military reputation as a capable army leader meant his memoirs were widely read, however, they followed the myth of the clean Wehrmacht faithfully. His memoirs do not discuss politics or offer a condemnation of Nazism.[99] Manstein was involved in the Holocaust, and he held the same antisemitic and racist views as Hitler.[100] In his memoirs Manstein emphasised the supposedly good relations the German army had with Soviet civilians. He wrote: "Naturally, there was no question of our pillaging the area. That was something the German army did not tolerate". From the outset the German army had treated the populace with savagery.[101] Manstein became overall commander of the Crimea while he was in command of the 11th Army. During this time his troops co-operated with the Einsatzgruppen and the peninsula became Judenfrei – 90,000 to 100,000 Jews were killed.[102] Manstein was sent to trial, convicted on nine charges of committing war crimes and sentenced to 18 years in jail.[102] The charges he was convicted of included: not preventing murders in his command area, shooting Soviet war prisoners, carrying out the Commissar Order, and allowing subordinates to shoot Soviet civilians in reprisals.[103] At the time of his trial, the first major crisis of the Cold War, the Berlin Blockade, had just ended. The Western powers wanted Germany to begin rearming to counter the Soviet threat. The West Germans indicated "not a single German soldier would don a uniform as long as any Wehrmacht officer remained in custody".[104] Consequently, a campaign started to secure the release of Manstein and the other jailed West German war criminals.[104]

Manstein's defence attorney during his trial was Reginald Paget. William Donovan, who had earlier helped Franz Halder, intervened and recruited his friend Paul Leverkuehn to assist the defence.[104] Paget helped strengthen the myth of the clean Wehrmacht, he defended the army's scorched earth policy on the basis that no army would fight by the rulebook. He defended the shooting of civilians who were armed but not engaged in any partisan action.[103] Both during and after the trial Paget denied Operation Barbarossa was a "war of annihilation". He downplayed the racist aspects of Barbarossa and the campaign to exterminate Soviet Jews. Instead, he argued that "the Wehrmacht displayed a large degree of restraint and discipline".[105] Paget's closing statement echoed the core of the myth of the clean Wehrmacht saying "Manstein is and will remain a hero amongst his people". He echoed the Cold War politics with the words: "If Western Europe is to be defencible, these decent soldiers must be our comrades".[103]

Captain Basil Liddell Hart, the British historian who was the most influential military historian in the English-speaking world during his lifetime, endorsed the "clean Wehrmacht" myth, writing with undisguised admiration about how the Wehrmacht had been the mightiest war machine ever built that would have won the war if only Hitler had not interfered with the conduct of operations.[78] Between 1949 and 1953, Liddell Hart was deeply involved in a public relations campaign for freedom for Manstein after a British military court convicted him of war crimes on the Eastern Front, which Liddell Hart called a gross miscarriage of justice.[106] The trial of Manstein was a turning point in the British people's perception of the Wehrmacht as Manstein's lawyer, the Labour MP Reginald Paget, waged a well oiled and energetic public relations campaign for amnesty for his client, enlisting many politicians and celebrities in the process.[107]

One celebrity who joined Paget's campaign, left-wing philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote in a 1949 essay that the 'enemy today' was the Soviet Union, not Germany, and, given how Manstein had become a hero to the German people, it was necessary for the Allied forces to free him so he was able to fight on their side in the Cold War.[106] Liddell Hart joined Paget's campaign for freedom for Manstein, and as Liddell Hart often wrote on military affairs in British newspapers, he played a key role in winning Manstein his freedom in May 1953.[106] Given Liddell Hart's general sympathy with the Wehrmacht, he depicted it in his books and essays as an apolitical force that had nothing to do with the crimes of the Nazi regime, a subject that did not much interest Liddell Hart in the first place.[78]

In arguing for Manstein, Paget had made contradictory arguments at the same time; namely Manstein and other Wehrmacht officers had known nothing of Nazi crimes at the time while at the same time they were opposed to the Nazi crimes that they were supposedly unaware of.[108] Paget lost the Manstein case with the British military tribunal presided over by Lieutenant General Frank Simpson finding Manstein supported Hitler's "war of annihilation" against the Soviet Union, enforced the Commissar Order, and as commander of the 11th Army assisted Einsatzgruppe C with massacring Jews in Ukraine, sentencing him to 18 years in prison for war crimes.[109] However, Paget did win the war for public opinion, persuading much of the British people that Manstein was wrongly convicted, and in May 1953 when the British government released Manstein, it caused no great controversy in Britain.[110] British historian Tom Lawson wrote that Paget was greatly helped by the fact that most of the British "Establishment" naturally sympathised with the traditional elites in Germany, seeing them as people much like themselves, and for members of the "Establishment" like Archbishop George Bell the mere fact that Manstein was a German Army officer and a Lutheran who went to church regularly "...was enough to confirm his opposition to the Nazi state and therefore the absurdity of the trial".[111]

After the war, the West German government bought the release of their war criminals.[112] The British government, concerned with the growing threat, wanted to encourage the West Germany to join the proposed European Defence Community and NATO. The British decided that releasing a few "iconic" war criminals was a price worth paying to prevent any part of West Germany from joining the East.[57] Celebrities and historians joined the campaign to secure the release of Manstein.[106]

The "Lost Cause" of Nazi Germany

[edit]American historians Ronald Smelser and Edward J. Davies noted the close similarities of the "untarnished shield" myth of the Wehrmacht to the Lost Cause of the Confederacy myth, starting with the way that former Confederate officers such as Jubal Early and former Wehrmacht officers such as Franz Halder were most active in promoting these myths after their respective wars.[113] Both myths glorify the Confederate military and the Wehrmacht as superior fighting organisations led by deeply honourable, noble, and courageous men who were overwhelmed by inferior opponents by sheer numbers and materiel together with bad luck.[114] Just as the Lost Cause myth portrayed the Confederate leaders as honourable, but misguided American patriots who were wrong to try to break up the United States, but were still admirable men and great American heroes; the "clean Wehrmacht" myth likewise portrayed the Wehrmacht leaders as honourable German patriots who might have been wrong to fight for Hitler, but were still men worthy of the highest admiration.[115] Both myths seek to glorify the respective militaries of the Confederacy and Nazi Germany by first portraying the military leaders as men of the highest honour, and secondly by disassociating them from the causes that they fought for. In the Confederates' case, it was denied that they fought for white supremacy and slavery while in the case of the Wehrmacht it was denied that they fought for the völkisch ideology of Nazi Germany.[115]

Both myths emphasised the respective militaries as forces of order and protection against chaos by inferior elements. In the case of the South, the Reconstruction period was portrayed by the Lost Cause mythologists as a nightmarish time when black men freed from slavery supposedly ran amok in a violent crime wave at the expense of the law-abiding white population of the South, thus implicitly justifying the Confederate struggle.[116] In the case of Germany, the war on the Eastern Front is portrayed as a heroic defensive struggle to protect "European civilisation" against the "Asiatic hordes" of the Red Army, who were always portrayed in the darkest of terms.[116] Israeli historian Omer Bartov noted that Nazi propaganda during the last days of the Nazi dictatorship pictured the war of the Eastern Front in the starkest and most extreme terms, as it was asserted that the Wehrmacht "... were defending humanity against a demonic invasion while simultaneously hoping to sow dissent between the Soviet Union and the Allied Forces. Though not successful in preventing the total collapse of the Third Reich, these efforts did bear fruit in another important sense, for they both prepared the ground for the FRG's [Federal Republic of Germany] eventual alliance with the West, and provided the Wehrmacht's apologists with a forceful and politically useful argument, even if it conveniently confused cause and effect".[117] And finally just as the "Lost Cause" myth promoted the image of the faithful black slave, happy to serve his or her masters, the "clean Wehrmacht" myth by emphasising the role of the Russian Liberation Army and other collaborationist units fighting alongside the Wehrmacht similarly gave the image of the Slavs happy to welcome the Wehrmacht as their liberators and saviours.[116] By focusing on the Wehrmacht as liberators, the narrative tended to distract attention from war crimes committed in the Soviet Union.[116] The involvement of the collaborationist units raised in the Soviet Union in the Holocaust was never mentioned.[118]

Initially, when Operation Barbarossa was launched in 1941, the peoples of the Soviet Union were portrayed in Nazi propaganda as untermenschen (sub-humans) who were threatening "European civilisation", and for whom there was to be no sympathy or compassion.[116] From 1943 onward there was a change in Nazi propaganda as the peoples of the Soviet Union with the exception of the Jews were portrayed as oppressed by the "Jewish Bolsheviks" whom Germany was fighting to liberate.[116] Both strands of Nazi propaganda found their way into the "clean Wehrmacht" myth. On one hand, the emphasis on atrocities committed by the "Asian" Red Army soldiers echoed the wartime propaganda theme of the "Asiatic hordes" laying waste to civilisation. On the other hand, the theme of the Vlasov Army as allies of the Wehrmacht echoed the wartime propaganda theme of the war against the Soviet Union as a noble struggle to freedom.[116] In this respect, there was a difference in the sense that the "Lost Cause" myth portrayed slaves who did not want their freedom while by contrast the "clean Wehrmacht" myth portrayed the Wehrmacht as liberators.[116] However, just as the "Lost Cause" myth portrayed submissive slaves who rejected freedom because their masters treated them so well, in the "clean Wehrmacht" myth, there is never any suggestion of equality between the Germans and the Soviet peoples, and the Vlasov Army are always portrayed as submissively looking up to their German liberators for guidance and leadership.[116] The exotic members of the Vlasov Army such as the Cossacks were portrayed as romantic, but savage; people worthy enough to be allies of the Wehrmacht, but not really their equals.[119]

End of the myth

[edit]

The myth of the clean Wehrmacht did not come to an end with any single event; rather, it ended with a series of events over many decades.[120] The myth predominated in the public mind in 1975. Omer Bartov praised "the efforts of a few outstanding and courageous German scholars" to challenge the myth starting in 1965.[76] The first German historian to challenge the myth was Hans-Adolf Jacobsen in his essay on the Commissar Order in the 1965 book Anatomie des SS Staates.[121] In 1969, Manfred Messerschmidt published a book on ideological indoctrination in the Wehrmacht, Die Wehrmacht im NS-Staat: Zeit der Indoktrination, which did not deal with war crimes directly, but challenged the popular claim of an "apolitical" Wehrmacht that had largely escaped Nazi influence.[121] The year 1969 also saw the publication of Das Heer und Hitler: Armee und nationalsozialistisches Regime by Klaus-Jürgen Muller and the essay "NSDAP und 'Geistige Führung' der Wehrmacht" by Volker R. Berghahn, the former dealing with the army's relationship with Hitler and the latter with the role of the "educational officers" in the Wehrmacht.[121] In 1978, Christian Streit published Keine Kameraden dealing with the mass murder of three million Soviet POWs, which was the first German book on the topic.[121] 1981 saw two books dealing with the co-operation of the Wehrmacht with the Einsatzgruppen, namely Die Behandlung sowjetischer Kriegsgefangener im "Fall Barbarossa" Ein Dokumentation by war crimes prosecutor Alfred Streim and Die Truppe des Weltanschauungskrieges: Die Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD, 1938–1942 by historians Helmut Krausnick and Hans-Heinrich Wilhelm.[121] In 1978, Streit's Keine Kameraden exposed the responsibility of the Wehrmacht for the death of over 3 million Soviet prisoners of war.[122] Starting in 1979, historians of the Militargeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Military Research Office) started publishing the official history of Germany in the Second World War, and the successive volumes have been very critical of the Wehrmacht's leaders.[121]

German historians critical of the myth were denounced by large sections of the German public and were told they had "fouled their own nest".[123] In 1986, the Historikerstreit ("historians' quarrel") began. The debate was supported with television programmes and by newspapers and publishers.[1] The Historikerstreit did not contribute any new research, but the efforts of the "revisionist" conservative historians such as Ernst Nolte and Andreas Hillgruber were marked by an angry nationalist tone.[124] Nolte and Hillgruber sought to "normalise" the German past by portraying the Holocaust as a defensive reaction to the Soviet Union and demanding "empathy" for the last stand of the Wehrmacht as it attempted to stop the "Asiatic flood" into Europe.[124] Bartov called the Historikerstreit a "rear-guard action" against the trends in German historiography.[124] Bartov noted that even historians who were critical of the Wehrmacht tended to write history very much in the traditional manner, namely history "from above" by focusing on actions of the leaders.[125] The tendency for social historians to write "history from below", especially Alltagsgeschichte ("history of everyday life") beginning in the 1970–80s opened up new avenues of research by looking at the experiences of ordinary German soldiers.[125] Such studies tended to confirm what the ordinary soldiers claimed to be up against on the Eastern Front, thanks to indoctrination propaganda,[16] many German troops regarded the Soviets as sub-human, leading to what Bartov called the "barbarisation of warfare".[126]

The year 1995 proved to be a turning point in German public consciousness with the opening in Hamburg of the Wehrmachtsausstellung ("Wehrmacht Exhibition"); the Hamburg Institute for Social Research initiated the touring exhibition, which exposed war crimes of the Wehrmacht to a wider audience focussing on the hostilities as a German war of extermination.[1] The exhibition was designed by Hannes Heer. The tour lasted for four years and travelled to 33 German and Austrian cities. It created a long-running debate and reappraisal of the myth.[1] The exhibition showed graphic photographs of war crimes committed by the Wehrmacht and interviewed those who had been party to the war itself. The soldiers who had been in the war mostly acknowledged the crimes but denied personal involvement. Some former soldiers offered Nazi-like justifications.[127] The impact of the exhibition was described as explosive. The German public had become accustomed to seeing "unspeakable deeds" with images of concentration camps and the SS. The exhibition showed 1,380 pictures of the Wehrmacht complicit in war crimes. The pictures had been taken mostly by the soldiers themselves, out in the countryside, far away from the concentration camps and the SS.[128] Heer wrote: "The creators of these photographs are present in their images – laughing, triumphant, or businesslike" and "this place is, in my opinion, at the centre of Hitler's Wehrmacht, standing inside the 'heart of darkness'".[129] Heer argues the war crimes had been covered up by scholars and former soldiers.[128][130] An outcry then ensued with the breaking of an age-old taboo. The organisers did not quantify the number of soldiers who had carried out war crimes. Historian Horst Möller wrote the number was "many tens of thousands".[131]

Further confirmation of the Wehrmacht's role came with the publication in 1996 of 1.3 million cables sent from the SS and the Wehrmacht units operating in the Soviet Union in the summer and autumn of 1941 which had been intercepted and decrypted by the British Government Code and Cipher School, and then shared with the U.S. National Security Agency, which chose to publish them.[126] Bartov wrote: "Although much of this has been known before, these documents provide more details on the beginning of the Holocaust and the apparently universal participation of German agencies on the ground in its implementation".[126]

In 2000, historian Truman Anderson identified a new scholarly consensus centering around the "recognition of the Wehrmacht's affinity for key features of the National Socialist world view, especially for its hatred of communism and its anti-Semitism".[132] Historian Ben H. Shepherd writes, "Most historians now acknowledge the scale of Wehrmacht's involvement in the crimes of the Third Reich".[133] In 2011, German military historian Wolfram Wette called the clean Wehrmacht thesis a "collective perjury".[134] The war-time generation maintained the myth with vigour and determination. They suppressed information and manipulated government policy, with their passing there was insufficient pressure to maintain the deceit.[135]

Jennifer Foray, in her 2010 study of the Wehrmacht occupation of the Netherlands, asserts that: "Scores of studies published in the last few decades have demonstrated that the Wehrmacht's purported disengagement with the political sphere was an image carefully cultivated by commanders and foot soldiers alike, who, during and after the war, sought to distance themselves from the ideologically driven murder campaigns of the National Socialists".[136]

Alexander Pollak writing in Remembering the Wehrmacht's War of Annihilation used his research into newspaper articles and the language they used, to identify ten structural themes of the myth. The themes included focusing on a small group of the guilty, the construction of a symbolic victim event – the Battle of Stalingrad, minimising war crimes by comparing them to Allied misdeeds, denying responsibility for starting the war, using the personal accounts of individual soldiers to extrapolate behaviour of the whole Wehrmacht, writing heroic obituaries and books, claiming the naivety of the ordinary soldier, and claiming orders had to be carried out.[137] Heer et al. conclude the newspapers conveyed only two types of events: those that would engender a feeling of empathy with Wehrmacht soldiers and to portray them as victims of Hitler, the OKH, or the enemy; and those that involved crimes by the Allied forces.[138]

Pollak, examining the structural themes of the myth, said where blame could not be dismissed the print media limited its scope by focusing the blame firstly on Hitler and secondly on the SS. By the 1960s a "Hitler craze" had been created and the SS were being described as his ruthless agents. The Wehrmacht had been detached from involvement in war crimes.[139] The Battle of Stalingrad was invented as a victim event by the media. They described the Wehrmacht as having been betrayed by the leadership and left to die in the freezing cold. This narrative focuses on individual soldiers who struggled to survive, engendering sympathy for the privations and harsh conditions. The War of Annihilation, the Holocaust, and racial genocide that had been carried out are not discussed.[140] The media minimised German war crimes by comparing them to the behaviour of the Allies. In the 1980s and 1990s the media became preoccupied with the bombing of Dresden to argue the Allies and the Wehrmacht were equally culpable. Newspaper articles routinely showed dramatic pictures of Allied crimes but rarely ones depicting the Wehrmacht.[141]

Pollak notes that the honour of the Wehrmacht is affected by the question of who started the war. He remarks that the media blame Britain and France for the "disgraceful" Treaty of Versailles, that they see as triggering German militarism. They blame the Soviet Union for signing the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Germany that subsequently encouraged Hitler to invade Poland. Some commentators discussed the need for a preventive war which supposed the Soviet Union intended to invade Germany.[142] The print media retold personal soldiers' accounts which, while an "authentic" recounting of perceived events, can be construed narrowly and placed in any wider context. The tragedies of "one soldier" are supposedly symptomatic of "tens of thousands of others", while the War of Annihilation, which the soldier had been part of, is airbrushed out.[143] A central theme of the myth is the description of soldiers as naïve, apolitical and without the mental faculty to understand the reasons for the war or its nature.[144] Soldiers are often described as having been forced to carry out orders, often under the fear of severe punishment, to excuse their actions. However, soldiers had a great deal of discretion and mostly chose their behaviour.[144]

Criminal orders

[edit]

During the planning of Operation Barbarossa, a series of "criminal orders" were devised. These orders went beyond international law and established codes of conduct.[145] The Commissar Order and the Barbarossa decree allowed German soldiers to execute civilians without fear they would later be tried for war crimes by the German state.[146] German historian Felix Römer studied the implementation of the Commissar Order by the Wehrmacht, publishing his findings in 2008. It was the first complete account of the application of the order by the Wehrmacht's combat formations. Römer's research shows that over 80% of German divisions on the Eastern Front filed reports detailing the murder of the Red Army's political commissars. Soviet statistics state 57,608 commissars were killed in action and 47,126 were reported missing, the majority of whom were killed utilising the order.[147]

Römer wrote the records which "prove that it was Hitler's generals who executed his murderous orders without scruples or hesitations". Wolfram Wette, reviewing the book, notes the sporadic objections to the order were not fundamental. They were driven by military necessity and the cancellation of the order in 1942 was "not a return to morality, but an opportunistic course correction". Wette concludes: "The Commissar Order, which had always had a particularly strong influence on the image of the Wehrmacht because of its obviously criminal character, had finally been clarified. Once again the observation had confirmed itself: the deeper the research penetrates into the military history, the gloomier the picture becomes".[148]

In 1941, the Wehrmacht took 3,300,000 Soviet soldiers as prisoners of war. By February 1942, two million of these were dead. 600,000 were shot because of the Commissar Order. Most of the rest died from criminal mistreatment. Once captured, Soviet POWs were marched into holding pens where they had no shelter, no medical treatment, and given minuscule rations. Forced labour became a death sentence. German Quartermaster-General Eduard Wagner declared, "prisoners incapable of work in the prison camps are to starve".[149] Friedrich Freiherr von Broich, while being secretly taped at Trent Park, recalled his memories of prisoners of war. He said the prisoners "at night howled like wild beasts" from starvation. Adding "we marched down the road and a column of 6,000 tottering figures went past, completely emaciated, helping each other along ... Soldiers of ours on bicycles rode alongside with pistols everyone who collapsed was shot and thrown into the ditch".[150] Wehrmacht troops shot civilians on the slightest pretext of partisan involvement and massacred whole villages that were supposedly protecting them.[151] Omer Bartov writes in The Eastern Front: 1941–1945 German Troops and the Barbarisation of Warfare that numerous interrogations by Germans had determined Soviet troops would rather die on the battlefield than be taken prisoner.[152]

The racist ideology of the campaign combined with "criminal orders", such as the Commissar Order, brought about a vicious circle of deepening violence and murder. The Wehrmacht endeavoured to "pacify" the population, but the civilians increased partisan activity. In August 1941, the II Corps ordered that "partisans are to be publicly hanged and left hanging for some time".[153] Public hangings became commonplace. Records of the reason for the murders included "feeding a Russian soldier", "wandering about", "trying to escape", and "for being an assistant's assistant of the partisans".[154] Bartov writes that the civilian population had also been de-humanised resulting in the barbarisation of warfare. The final phase of this barbarisation was the "scorched earth" policy utilised by the Wehrmacht as they retreated.[155]

Participation in the Holocaust

[edit]

Walter von Reichenau issued the Severity Order in October 1941 that stated the essential aim of the campaign was the destruction of the 'Jewish–Bolshevik system'. The order was described as a model by the Wehrmacht leadership and relayed to numerous commanders. Manstein relayed it to his troops as: "The Jew is the middle man between the enemy at the rear [...] The soldier must summon understanding for the necessity for the hard redress against the Jews". To functionally justify the murder of Jews they were equated to partisan resistance fighters.[157] A wide-scale anti-Semitic consensus already existed amongst ordinary Wehrmacht soldiers.[158]

Army Group Centre began massacring the Jewish population on day one. In Białystok, Police Battalion 309 shot dead large numbers of Jews in the street, then corralled hundreds of Jews into a synagogue they set on fire.[159] The commander of rear military zone 553 recorded 20,000 Jews had been killed by Army Group South in his zone up to the summer of 1942. In Belorussia, over half the civilians and POWs murdered were killed by Wehrmacht units, many Jews were among them.[160]

American historian Waitman Wade Beorn writing in his book Marching into Darkness examined the Wehrmacht's role in the Holocaust in Belarus during 1941 and 1942. The book investigates how German soldiers progressed from tentative killings to sadistic "Jew games".[161] He writes that "Jew hunting" became a pastime. Soldiers would break the monotony of duty in the countryside by rounding up Jews, taking them to the forests and releasing them so they could be shot as they ran away.[162] Beorn writes that individual Wehrmacht units were rewarded for brutal behaviour and explains how this created a culture of ever deeper involvement with the regime's genocidal aims.[163] He discusses the Wehrmacht's role in the Hunger Plan, Nazi Germany's starvation policy.[164] He examines the Mogilev Conference in September 1941 which marked a dramatic escalation of violence against the civilian population.[165] The book looks at several military formations and how they responded to orders to commit genocide and other crimes against humanity.[166]

The Wehrmacht carried out mass shootings of Jews, near Kiev, on 29 and 30 September in 1941. At Babi Yar 33,371 Jews were marched to a ravine and shot into pits. Some of the victims died as a result of being buried alive in the pile of corpses.[167] In 1942, mobile SS killing squads engaged in a swathe of massacres in conjunction with the Wehrmacht. Approximately 1,300,000 Soviet Jews were murdered.[167]

See also

[edit]Related to Nazi Germany:

- Austria victim theory

- Bandenbekämpfung

- Denazification

- German atrocities committed against prisoners of war during World War II

- German collective guilt

- HIAG (acronym translated as: "Mutual aid association of former Waffen-SS members")

- The Myth of the Eastern Front

- Nazism and the Wehrmacht

- Rommel myth

- Speer myth

- War crimes of the Wehrmacht

Similar phenomena elsewhere:

- Italiani brava gente – a similar construct in Italian post-war memory

- Japanese history textbook controversies – a similar construct in Japanese post-war memory.

- Lost Cause of the Confederacy – Pseudohistory that portrays the Confederate States of America as having a noble justification for the American Civil War other than the desire to preserve slavery

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wette 2007, p. 269.

- ^ Beorn 2014, pp. 12–17.

- ^ Harrisville, David A. (2021). The Virtuous Wehrmacht: Crafting the Myth of the German Soldier on the Eastern Front, 1941-1944. Cornell University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-5017-6006-8.

- ^ Plischke, Elmer (1983). "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1951, Volume III: European Security and the German Question. Part 1, Dept. of State Pub. 8982. Part 2, Dept. of State Pub. 9113. Washington: U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1981. Pp. xxxiv, 2065. Index in part 2". American Journal of International Law. 77 (2): 446. doi:10.2307/2200893. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2200893 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 64.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 158.

- ^ Müller 2016, p. 16.

- ^ "Chapter I – The German Military System". Handbook on German Military Forces. War Department. 15 March 1945. p. [I-57]. Technical Manual TM-E 30-451. Retrieved 14 August 2019 – via Hyperwar Foundation.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 195.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 292–297.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 222.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 25.

- ^ Förster 1988, p. 21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stahel 2009, pp. 96–99.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Evans 1989, p. 59.

- ^ Evans 1989, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Förster 2005, p. 127.

- ^ Ingrao 2013, p. 140.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 199–201.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, p. 38.

- ^ Hilberg 1985, p. 301.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 16.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 46.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 48.

- ^ Datner, Szymon (1962). Crimes Committed by the Wehrmacht During the September Campaign and the Period of Military Government. Drukarnia Univ.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2007). War of Annihilation: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front, 1941. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-4482-6.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2 October 2012). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03297-6. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Böhler, Jochen (2006). Auftakt zum Vernichtungskrieg: die Wehrmacht in Polen 1939 (in German). Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-596-16307-6. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 27.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 30.

- ^ Beorn 2014, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Beorn 2014, pp. 65, 76.

- ^ Herbermann, Nanda (2000). The Blessed Abyss: Inmate #6582 in Ravensbrück Concentration Camp for Women. Wayne State University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8143-2920-7.

- ^ Yudkin, Leon (1993). Hebrew literature in the wake of the Holocaust. International Centre for University Teaching of Jewish Civilisation. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. pp. 13–22. ISBN 0-838-63499-0. OCLC 27265678.

- ^ Lenṭin, Ronit. (2000). Israel and the daughters of the Shoah: reoccupying the territories of silence. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 33–34. ISBN 1-57181-774-3. OCLC 44720589.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gmyz, Cezary (22 April 2007). "Seksualne niewolnice III Rzeszy" [Sex slaves of the Third Reich]. WPROST.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Kay, Alex J.; Stahel, David (2018). "Part IV. Wehrmacht". Mass Violence in Nazi-Occupied Europe. Indiana University Press. pp. 173–194. doi:10.2307/j.ctv3znw3v.11. ISBN 9780253036810. JSTOR j.ctv3znw3v.11.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Wette 2007, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 136.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 137.

- ^ Herbert, Ulrich; Aly, Götz (2000). National Socialist Extermination Policies: Contemporary German Perspectives and Controversies. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-751-8.

- ^ Gumz, Jonathan E. (2001). "Wehrmacht Perceptions of Mass Violence in Croatia, 1941–1942". The Historical Journal. 44 (4): 1015–1038. doi:10.1017/S0018246X01001996. ISSN 0018-246X. JSTOR 3133549. S2CID 159947669.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hébert 2010, pp. 99–101.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wette 2007, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Jump up to: a b von Lingen 2009, p. 161.

- ^ Jump up to: a b von Lingen 2009, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Jump up to: a b von Lingen 2009, p. 163.

- ^ Jump up to: a b von Lingen 2009, p. 162.

- ^ von Lingen 2009, p. 189.

- ^ von Lingen 2009, pp. 162–163.

- ^ von Lingen 2009, pp. 163–167.

- ^ von Lingen 2009, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Large 1987, p. 80.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Jump up to: a b von Lingen 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 74.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wette 2007, p. 236.

- ^ Corum 2011, p. 24.

- ^ S. Miles, Aileen; L. Meyer, Alfred (eds.). "Information Bulletin February 1951". search.library.wisc.edu. Information Bulletin, Monthly Magazine of the Office of the U.S. High Commissioner for Germany (U.S. Department of State). p. 37. Retrieved 23 September 2024 – via University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 236–238.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wette 2007, p. 239.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wette 2007, pp. 240–241.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 240.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 241.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 242.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 247.

- ^ Reichelt, Hans (2007). Die deutschen Kriegsheimkehrer. Was hat die DDR für sie getan? (Eastern ed.). Berlin: University of Michigan. ISBN 978-3-36001-089-6.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 229–231.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wette 2007, p. 251.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wette 2007, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wette 2007, p. 230.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 345.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bartov 1997, p. 165.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 90.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wette 2007, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 110.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 111.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 111–113.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wette 2007, p. 257.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 56, 65.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 65.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wette 2007, p. 231.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 66.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wette 2007, p. 232.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 229.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 71.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 63.

- ^ Nuremberg Day 200 Von Manstein (translated captions). Robert H. Jackson Center. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 92.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 96.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 99.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 101.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 100.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 225.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wette 2007, p. 226.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Lawson 2006, p. 159.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 224–226.

- ^ Lawson 2006, pp. 159–160.

- ^ von Lingen 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 87.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 86.

- ^ Bartov 1999, p. 147.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, p. 83.

- ^ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 181–185.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 270–272.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Bartov 1997, p. 166.

- ^ Harrisville 2021, p. 4.

- ^ Wette 2007, pp. 275–277.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bartov 1997, p. 171.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bartov 1997, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bartov 1997, p. 168.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, p. 95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Heer et al. 2008, pp. 238–243.

- ^ Tymkiw 2007, pp. 485–492.

- ^ Semmens, Kristin (2006), Review of Heer, Hannes. Vom Verschwinden der Täter: Der Vernichtungskrieg fand statt, aber keiner war dabei (in German) [About the disappearance of the perpetrators: The War of Annihilation took place, but no one was there.], H-German, H-Net, ISBN 978-3-35102-565-6

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, p. 239.

- ^ Anderson 2000, p. 325.

- ^ Shepherd 2009, pp. 455–456.

- ^ Zähe Legenden. Interview mit Wolfram Wette, in: Die Zeit vom 1. June 2011, S. 22

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 278.

- ^ Foray 2010, pp. 769–770.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, p. 137.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, p. 154.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, pp. 143–146.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, p. 146.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Heer et al. 2008, p. 152.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Stahel 2009, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 58.

- ^ Wette 2009.

- ^ Epstein 2015, p. 140.

- ^ Neitzel 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Epstein 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Bartov 1986, p. 118.

- ^ Bartov 1986, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Bartov 1986, p. 122.

- ^ Bartov 1986, p. 129.

- ^ Raptis & Tzallas 2005, p. 1.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Wette 2007, p. 28.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Heer et al. 2008, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 191.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 92.

- ^ Beorn 2014, p. 239.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Epstein 2015, p. 157.

Bibliography

[edit]- Anderson, Truman (July 2000). "Germans, Ukrainians and Jews: Ethnic Politics in Heeresgebiet Sud, June—December 1941". War in History. 7 (3): 325–351. doi:10.1177/096834450000700304. S2CID 153940092.

- Bartov, Omer (1986). The Eastern Front, 1941–1945, German Troops and the Barbarisation of Warfare. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22486-9.

- Bartov, Omer (Fall 1997). "German Soldiers and the Holocaust: Historiography, Research and Implications". History & Memory. 9 (1/2): 162–188. doi:10.2979/HIS.1997.9.1-2.162.

- Bartov, Omer (1999). "Soldiers, Nazis and War in the Third Reich". In Christian Leitz (ed.). The Third Reich The Essential Readings. London, UK: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-63120-700-9.

- Beorn, Waitman (2014). Marching into Darkness. London, UK: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67472-550-8.

- Corum, James S. (2011). Rearming Germany. Boston, Ma.: Brill. ISBN 978-9-00420-317-4.

- Epstein, Catherine (2015). Nazi Germany Confronting the Myths. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-11829-479-6.

- Evans, Richard J. (1989). In Hitler's Shadow West German Historians and the Attempt to Escape the Nazi Past. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-39457-686-2.

- Foray, Jennifer (October 2010). "The 'Clean Wehrmacht' in the German-occupied Netherlands, 1940–5". Journal of Contemporary History. 45 (4): 768–787. doi:10.1177/0022009410375178. JSTOR 25764581. S2CID 154697957.

- Förster, Jürgen (Winter 1988). "Barbarossa Revisited: Strategy and Ideology in the East". Jewish Social Studies. 50 (1/2): 21–36. JSTOR 4467404.

- Förster, Jürgen (2005). Mark Erickson; Ljubica Erickson (eds.). Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-29784-913-1.

- Heer, Hannes; Manoschek, Walter; Pollak, Alexander; Wodak, Ruth (2008). The Discursive Construction of History: Remembering the Wehrmacht's War of Annihilation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-23001-323-0.

- Hébert, Valerie (2010). Hitler's Generals on Trial: The Last War Crimes Tribunal at Nuremberg. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-70061-698-5.

- Hilberg, Raul (1985). The Destruction of the European Jews. New York: Holmes & Meier. ISBN 978-0-84190-832-1.

- Ingrao, Christian (2013). Believe and Destroy: Intellectuals in the SS War Machine. Malden, Ma.: Polity. ISBN 978-0-74566-026-4.

- Large, David C. (1987). "Reckoning without the Past: The HIAG of the Waffen-SS and the Politics of Rehabilitation in the Bonn Republic, 1950–1961". The Journal of Modern History. 59 (1): 79–113. doi:10.1086/243161. JSTOR 1880378. S2CID 144592069.

- Lawson, Thomas (2006). The Church of England and the Holocaust: Christianity, Memory and Nazism. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84383-219-5.

- Müller, Rolf-Dieter (2016). Hitler's Wehrmacht, 1935–1945. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-81316-811-1. OCLC 971043078.

- Neitzel, Sönke (2005). Tapping Hitler's Generals: Transcripts of Secret Conversations 1942–45. London, UK: Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-84832-715-3.

- Shepherd, Ben H. (June 2009). "The Clean Wehrmacht, the War of Extermination, and Beyond". War in History. 52 (2): 455–473. doi:10.1017/S0018246X09007547. S2CID 159662860.

- Smelser, Ronald; Davies, Edward J. (2008). The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52183-365-3.

- Stahel, David (2009). Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East. Cambridge, Ma.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52176-847-4.

- Tymkiw, Michael (2007). "Debunking the myth of the saubere Wehrmacht". Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry. 23 (4): 485–492. doi:10.1080/02666286.2007.10435801. S2CID 193512224.

- von Lingen, Kerstin (2009). Kesselring's Last Battle: War Crimes Trials and Cold War Politics, 1945–1960. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-70061-641-1.

- Wette, Wolfram (2007). The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02577-6.

Online sources

[edit]- Raptis, Alekos; Tzallas, Thanos (2005). "Deportation of Jews of Ioannina" (PDF). Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue and Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2009.

- Wette, Wolfram (2009). "Mehr als dreitausend Exekutionen. Sachbuch: Die lange umstrittene Geschichte des 'Kommissarbefehls' von 1941 in der deutschen Wehrmacht" [More than three thousand executions. Non-fiction book: The long controversial history of the "Commissar Order" of 1941 in the German Wehrmacht]. Badische Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 22 December 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Adam, Thomas (2005). Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History: A Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-851-09628-0.

- Balfour, Michael Leonard Graham (1988). Withstanding Hitler in Germany, 1933–45. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00617-1.

- Biddiscombe, Perry (2006). The Denazification of Germany 1945–48. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-75242-346-3.

- Goldhagen, Daniel J. (1997). Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-679-77268-5.

- Harrisville, David A. (2021). The Virtuous Wehrmacht: Crafting the Myth of the German Soldier on the Eastern Front, 1941–1944. Cornell University Press.

- Hébert, Valerie (2012). "From Clean Hands to Vernichtungskrieg. How the High Command Case Shaped the Image of the Wehrmacht". In Priemel, Kim C.; Stiller, Alexa (eds.). Reassessing the Nuremberg Military Tribunals: Transitional Justice, Trial Narratives and Historiography. Berghahn Books. pp. 194–220. ISBN 978-0-85745-532-1.

- Hentschel, Klaus (2007). The Mental Aftermath: The Mentality of German Physicists 1945–1949. Translated by Ann M. Hentschel. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19920-566-0.

- Janowitz, Morris (September 1946). "German Reactions to Nazi Atrocities". American Journal of Sociology. 52 (2). University of Chicago Press: 141–146. doi:10.1086/219961. JSTOR 2770938. PMID 20994277. S2CID 44356394.

- Junker, Detlef (2004). The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War: A Handbook. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52179-112-0.

- Lewkowicz, N. (2008). The German Question and the Origins of the Cold War. Milan: IPOC.

- Marcuse, Harold (2001). Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933–2001. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55204-4.

- Merritt, Anna J.; Merritt, Richard L., eds. (1980). Public opinion in semi-sovereign Germany: the HICOG surveys, 1949–1955. U.S. Office of High Commissioner for Germany. Reactions Analysis Staff. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-00731-X.

- Taylor, Frederick (2011). Exorcising Hitler: The Occupation and Denazification of Germany. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-60819-503-9.

Online sources

[edit]- Howard, Lawrence E. (30 March 2007). "Lessons Learned from Denazification and de-Ba'athification" (PDF). Strategy Research Project for MSc in Strategic Studies. U.S. Army War College. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 July 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- The Department of State (1950). "Germany 1947–1949: The Story In Documents". Publication 3556. U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

External links

[edit]- Video interview with Jeff Rutherford, the author of Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front: The German Infantry's War, 1941–1944, via C-SPAN

- Uncovered files shed light on Hitler's Wehrmacht, article via Deutsche Welle

- "A Blind Eye and Dirty Hands The Wehrmacht's Crimes" – lecture by the historian Geoffrey P. Megargee, via the Wiener Library for the Study of the Holocaust and Genocide

- The Role of the German Army during the Holocaust: A Brief Summary – lecture by Geoffrey P. Megargee, via the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Killing the 'Clean' Wehrmacht: The Reality of the German Army and the Holocaust by Dr Waitman Beorn – lecture at the Holocaust Exhibition and Learning Centre based at the University of Huddersfield