Hamas government in the Gaza Strip

| Hamas government in the Gaza Strip | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Established | 14 June 2007 |

| State | Gaza Strip, State of Palestine |

| Leader | Ismail Haniyeh (2007–2017) Yahya Sinwar (2017–2024) |

| Headquarters | Gaza City |

| Website | pmc |

|

|---|

Hamas has governed the Gaza Strip in Palestine since its takeover of the region from rival party Fatah in June 2007.[1][2][3] Hamas' government was led by Ismail Haniyeh from 2007 until February 2017, when Haniyeh was replaced as leader of Hamas in the Gaza Strip by Yahya Sinwar.[4] Until October 2024, Yahya Sinwar was the leader of Hamas in the Gaza Strip. In January 2024, due to the ongoing Israel–Hamas war, Israel said that Hamas lost control of most of the northern part of the Gaza Strip.[5][6] In May 2024, Hamas regrouped in the north.[7][8]

After Hamas won the Palestinian legislative elections on 25 January 2006, Ismail Haniyeh was nominated Prime Minister of the Palestinian National Authority,[9] establishing a Palestinian national unity government with Fatah. This government effectively collapsed with the outbreak of the violent conflict between Hamas and Fatah. After the takeover of the Gaza Strip by Hamas on 14 June 2007, Palestinian Authority Chairman Abbas dismissed the Hamas-led government and appointed Salam Fayyad Prime Minister.[10] Though the new Ramallah-based Palestinian government's authority was claimed to extend to both the Palestinian territories, in effect it became limited to the West Bank, as Hamas did not recognize the dismissal and continued to rule the Gaza Strip.[11] Both administrations – Abbas' Fatah government in Ramallah and the Hamas government in Gaza – regarded themselves as the sole legitimate government of the Palestinian National Authority. The international community, however, recognized the Ramallah administration as the legitimate government.

Since the division between the two parties, there have been conflicts between Hamas and similar factions operating in Gaza, and with Israel, including the Gaza War of 2008–2009, the 2014 Gaza War and most notably the Israel–Hamas war.

The radicalization of the leadership of the Gaza Strip had previously motivated internal conflicts between different groups, in events like 2009 Hamas crackdown on Jund Ansar Allah, an al-Qaeda affiliated group, resulting in 22 people killed; and the April 2011 Hamas crackdown on Jahafil Al-Tawhid Wal-Jihad fi Filastin, a Salafist group involved in Vittorio Arrigoni's murder.[12][13]

Negotiations toward reconciliation between Fatah and Hamas, which were mediated by Egypt, produced a preliminary agreement in 2011, which was supposed to be implemented by May 2012 through joint elections. Despite the peace plan, Palestinian sources were quoted in January 2012 as saying that the May joint elections "would not be possible". In February 2012, Hamas' Khaled Meshal and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas signed the Hamas–Fatah Doha agreement. A unity government was sworn on 2 June 2014.[14] The government was supposed to exercise its functions in Gaza and the West Bank, and prepare for national elections, though that did not happen, with disagreements between the two parties.[15] With the failure of the national unity government, the Palestinian National Authority continued to exercise power only in the West Bank, while Hamas remained in power in the Gaza Strip.

History

Prelude to division

Conflict between Fatah and Hamas began simmering when Hamas won the Palestinian legislative elections in January 2006. Israel and the Quartet—comprising the United States, the European Union, Russia and the United Nations—demanded that the new Hamas government accept all previous agreements, recognize Israel's right to exist, and renounce violence; when Hamas refused, they cut off aid to the Palestinian Authority.[citation needed]

Major conflict erupted in Gaza in December 2006, when the Hamas executive authority attempted to replace the Palestinian police as the primary authority in Gaza.[16]

On 8 February 2007, Saudi-sponsored negotiations in Mecca produced an agreement on a Palestinian national unity government. The agreement was signed by Mahmoud Abbas on behalf of Fatah and Khaled Mashal on behalf of Hamas. The new government was called on to achieve Palestinian national goals as approved by the Palestine National Council, the clauses of the Basic Law and the National Reconciliation Document (the "Prisoners' Document") as well as the decisions of the Arab summit.[17]

In March 2007, the Palestinian Legislative Council approved formation a national unity government with 83–3 vote. Government ministers were sworn in by Abbas, the president on the Palestinian National Authority, at ceremonies held in Gaza and Ramallah. In June that year, Hamas took control of the Gaza Strip from the national unity government[18] after forcing out Fatah.

On 14 June 2007, Abbas announced the dissolution of the former unity government and declared a state of emergency. He dismissed Ismail Haniyeh as prime minister and appointed Salam Fayyad in his place, giving him the task of building a new government.[19] Nonetheless, Hamas rejected the decree of Abbas and said the Ismail Haniyeh government would remain in office[11] and continue to function as the government of the Palestinian National Authority.

June 2007 Hamas government

Takeover by Hamas

With Hamas in control of the Gaza Strip and Fatah in control of the West Bank, there were two de facto governments in the Palestinian territories, each claiming to be the legitimate government of the Palestinian people. On 14 June 2007, Abbas dismissed the Hamas-dominated PA government of March 2007, but Haniyye refused to accept the dismissal and declared the formation of a new Hamas government in June 2007, as West Bank resident Ministers in the Palestinian government were deposed by Fatah.

Palestinian police chief Kamal el-Sheikh ordered his men in the Gaza Strip not to work or obey Hamas orders. However, many Fatah members fled the Gaza Strip to the West Bank, and Fatah gunmen stormed Hamas-led institutions in the West Bank after the Battle of Gaza.[20][21]

Palestinian legislator Saeb Erekat said the PA officially has no control in the Gaza Strip. Hamas and Fatah accused each other of a coup d'état, with neither recognizing the authority of the other government.[11][22]

The United States, EU, and Israel have not recognized the Hamas government, but support Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas and Prime Minister Salam Fayyad's government in the West Bank. The Arab League called on all parties to stop the fighting and return the government to its status before the Battle of Gaza, which would be the 2007 unity government and not the new PA government appointed by Abbas. Although the United States does not officially recognize the Hamas government, it holds it "fully and entirely responsible for the Gaza Strip," United States Assistant Secretary of State Sean McCormack said.[21]

On 16 June 2007, Haniyeh declared Said Fanuna (officially a Fatah general who, in reality, distanced himself from Abbas) as the new security chief in the Gaza Strip, stating him as a "higher police command" than the West Bank-based police chief Kamal el-Sheikh of the Fatah.[20][23]

Internal and external conflicts

After the division of the two Palestinian parties, the West Bank remained relatively quiet, but the Gaza Strip was the scene of constant conflict between Hamas and various other rival Islamist factions opposed to the Hamas government. The 2008-2009 Gaza war between Hamas and Israel also occurred during this time.[citation needed]

In 2009, a radical Salafist cleric declared an "Islamic Emirate" in Gaza, accusing Hamas of failing to implement full Sharia law. The radicalization of the Gaza Strip and attempt to undermine Hamas authority resulted in the 2009 Hamas crackdown on Jund Ansar Allah, an Al-Qaeda affiliated group, that lasted two days and resulted in 22 deaths.[citation needed]

Reports in March 2010 suggested that Ahmed Jabari described the security situation in Gaza as deteriorating, and that Hamas was starting to lose control.[24] Nevertheless, the Hamas continued to exercise authority.

In April 2011, Hamas conducted another crackdown, this one on a Salafist group reportedly involved in Vittorio Arrigoni's murder.[12][13]

In March 2019, Gaza witnessed widespread protests, reflecting dissatisfaction with the severe living conditions, which were marked by a 70% unemployment rate among young people. The scale and intensity of the protests were unprecedented since Hamas assumed full control of Gaza in 2007. In response, Hamas took harsh measures: Dozens of individuals, including activists, journalists, and human rights workers, have been beaten, arrested and subjected to home raids.[25][26]

During the Arab Spring

Hamas praised the Arab Spring, but its offices in Damascus were directly affected by the Syrian Civil War. The Hamas leader Khaled Mashal eventually relocated to Jordan, and Hamas began to distance itself from the Syrian government in the backdrop of the Syrian civil war. The evacuation of Hamas offices from Damascus may be the principal reason for the Doha ratification agreement signed by Abbas and Mashal, but it was also suggested that this was done due to a rift between Hamas Government in Gaza and the external Hamas office, led by Mashal. Essentially, the Doha deal does not reflect any real reconciliation among the factions of the Hamas Government.[citation needed]

Following the events of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, and the consequent election of an Islamist president in Egypt, Hamas relations with Egypt improved, and in 2012 Egypt eased the permit requirements for Palestinians from Gaza entering through the Rafah crossing. In July 2012, reports circulated that the Hamas Government was considering declaring the independence of the Gaza Strip with the help of Egypt.[27]

September 2012 Hamas government

In September 2012, Ismail Haniyeh, head of the Hamas government in Gaza, announced a cabinet reshuffle, appointing seven new ministers including a new finance minister. Haniyeh said the reshuffle was "normal procedure after nearly six years of work by some ministers and in order to achieve specific goals for the current period."[28]

Haniyeh said he had postponed carrying out the cabinet reshuffle several times to allow time for a reconciliation process between Fatah and Hamas to succeed. The two sides have been trying to implement the terms of an April 2011 reconciliation deal for months now, but appear no closer to achieving either the consensus interim government or the legislative and presidential elections called for by the agreement.[28] This followed a May 2012, a new Fatah government appointment in the West Bank, in a move that has angered the Hamas government in Gaza, which slammed the decision to form a new cabinet, accusing Abbas' Palestinian Authority and the Fatah movement he heads of abandoning reconciliation.[29]

2016 Hamas administration

The Hamas government of 2016 is the third de facto Hamas government in the Gaza Strip since the Hamas takeover of the Gaza Strip in 2007. On 17 October 2016 it as announced that the Supreme Administrative Committee, which is in charge of the conduct of Gaza's ministries, had carried out a Cabinet reshuffle in active ministries and a change the positions of 16 deputy ministers and directors general in government institutions.[30] The new administration was composed of Deputy Ministers, Directors General and other high-level officials, not directly bound to the Ramallah administration. It was initially speculated that the 2016 Hamas government was an attempt to return Ismail Haniyeh to full control of the Gaza Strip.[30] As part of the government changes, the Ministry of Planning was abolished.[30]

According to some views, the third Hamas cabinet de facto succeeded the failed 2014 national unity government, which was reshuffled by Palestinian president Mahmud Abbas in July 2015 without Hamas consent and was announced by Hamas as expired on 19 October 2016. "Coalition for Accountability and Integrity – Aman" said that the formation of this committee was a declaration of a new government in the Gaza Strip.[30] Youssef Mahmoud, the spokesman for the consensus Palestinian government, said that every action made in Gaza without the consensus government's approval is illegitimate and not recognized by the Ramallah government.[30] Ismail Haniyeh, the Prime Minister of the 2007 and 2012 Hamas-led governments, considers the 2015 Fatah-dominated government in Ramallah as illegitimate. The Hamas government of 2016 exercises de facto rule over the Gaza Strip, supported by the Palestinian Legislative Council, which is dominated by members of Hamas.

In March 2017, the Fatah dominated government in the West Bank expressed its concern that the Gaza administration is being upgraded by Hamas into a full-fledged 'shadow government'.[31] Further in April and May 2017, Abbas vowed to take unprecedented measures to end the division – cutting 30–50% of Gaza Strip-based employees of the Palestinian administration, suspending social assistance to 630 families and preventing Gazan cancer patients from reaching treatment in Jerusalem or Israeli hospitals. In addition, Ramallah-based government stopped paying for Gazan electricity bills to Israel and on April 28 Abbas approved early retirement of 35,000 military personnel in Gaza (originally funded by the Ramallah administration) and cut financial aid to former Hamas prisoners.

On 14 June 2021, Hamas announced that Issam al-Da’alis was the new prime minister of the Hamas government in Gaza, succeeding Mohammed Awad who resigned after two years in the position. The PA previously expressed opposition to the formation of a Hamas government in the Gaza Strip. In 2017, Hamas announced its decision to dismantle the administrative committee it had set up as a de facto government in the Gaza Strip, which was taken to promote reconciliation with the PA.[32]

2023 Israel–Hamas war

Following the outbreak of the 2023 Israel–Hamas war and the Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip in early November 2023, Hamas complete control of the Gaza Strip was weakened as Israeli forces kept advancing.[33] On January 6, 2024, the Israeli government stated that actual Hamas rule in the northern part of the Gaza Strip was eliminated due to Israeli military advance.[34] By 18 January, the IDF stated that Hamas had begun to rebuild its armies in the occupied parts of Northern Gaza. The IDF had previously stated these armies were stripped of military capabilities but by 18 January the fighting strength of many battalions had been significantly restored.[35] Some change occurred from late January 2024 onward, as it was reported that Hamas managed to revive some of its governing abilities in parts of Gaza city from which Israeli forces withdrew.[36]

At the same time, some level of planning for the future governance following that war began by both the Israeli and the US governments.[37] In late December 2023, the Egyptian government proposed the creation of a temporary technocratic Palestinian administration for the Gaza Strip until new Palestinian legislative elections are held.[38] In late February 2024, the Israeli government presented its first official plan for the future control of the Gaza Strip.[39][40] The possibility of an Israeli military government over the Gaza Strip has also been considered by the Israeli government. Military sources estimated its cost at NIS 20 billion a year.[41] According to media reports, defense minister Yoav Gallant opposed the idea of Israeli military government.[42][43]

Despite Israeli military advance, parts of the Gaza Strip remained under de-facto control by Hamas, even though it is difficult to assess the real level of control. Yahya Sinwar remained in control of some areas until his assassination in October 2024. Following the assassination, Hamas was facing the task of choosing another leader.

Government and politics

|

|---|

|

|

In 2006, Hamas won the 2006 Palestinian legislative elections and assumed administrative control of Gaza Strip and West Bank. In 2007, Hamas led a military victory over Fatah, the secular Palestinian nationalist party, which had dominated the Palestinian National Authority. As a result, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas declared state of emergency and released Hamas Prime Minister Haniye – a move not recognized by the Hamas party, which de facto continued administration and military control of the Gaza Strip, while in the PNA controlled West Bank another government was established with Fatah domination.[44][45]

Both regimes – the Ramallah and Gaza government regard themselves as the sole legitimate government of the Palestinian National Authority. Egyptian-mediated negotiations toward reconciliation between the Fatah and the Hamas government produced a preliminary agreement, planned to be implemented by May 2012 in joint elections. To date, the Hamas government is only economically bonded with the Ramallah-based Palestinian National Authority, performing the governing over the Gaza Strip independently.

Hamas operates three internal security organisations: the General Security Service, Military Intelligence, and the Internal Security Service. The General Security Service is officially part of Hamas's political arm and works to stifle dissent. Military Intelligence is dedicated to obtaining information about Israel, and the Internal Security Service is a part of the interior ministry. The New York Times reported that the General Security Service employed 856 people before the 2023 war.[46]

Governing structure

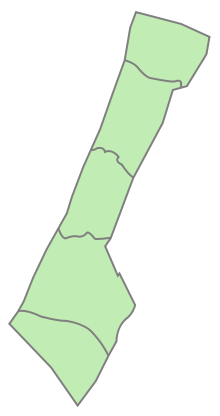

Governorates of the Gaza Strip are five administrative districts:

- Deir al-Balah Governorate

- Gaza Governorate

- Khan Yunis Governorate

- North Gaza Governorate

- Rafah Governorate

After the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993, the Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza Strip were divided into three areas (Area A, Area B, and Area C) and 16 governorates under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian National Authority. In 2005, Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip, enlarging the administered Palestinian territories in that region. In 2007, following the War of Brothers in the Gaza Strip between Fatah and Hamas, the latter took over the area and expelled all Palestinian Authority officials, affiliated with Fatah. It has since administered the five districts, including eight cities.

Leadership

Hamas leader in the Gaza Strip

| No. | Portrait | Name (born-died) |

Term of office | Deputy | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | Time in office | |||||

| Leader of Hamas in the Gaza Strip | |||||||

| 1 |

|

Ismail Haniyeh إسماعيل هنية (c. 1962–2024) |

14 June 2007 | 13 February 2017 | 9 years, 244 days | Unknown | [47] |

| 2 |

|

Yahya Sinwar يحيى السنوار (1962–2024) |

13 February 2017 | 16 October 2024 † | 7 years, 246 days | Khalil al-Hayya (March 2021 – 16 October 2024)[48][49] |

[50] |

Security

After having confronted and disarmed significant Fatah-supporting hamullas, or clans, Hamas had a near monopoly on arms inside Gaza.[51] In March 2010, however, Ahmed Jabari described the security situation in Gaza as deteriorating and said Hamas was starting to lose control.[24] In June 2011, the Independent Commission for Human Rights published a report whose findings included that the Palestinians in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were subjected in 2010 to an "almost systematic campaign" of human rights abuses by the Ramallah and Hamas administrations, as well as by Israeli authorities, with the security forces belonging to the Ramallah and Hamas government being responsible for torture, arrests and arbitrary detentions.[52]

A 2012 report by Nathan J. Brown found increasing authoritarian actions in the administration of the Gaza Strip, with opposition parties restricted from performing public activities. Brown found that the Hamas government increasingly took on tendencies seen in past administrations by the rival Fatah party, which ruled over the West Bank. Parties affiliated with Fatah, as well as affiliated NGOs, have been subjected to stricter controls. One such NGO, the Sharek Youth Forum, was closed in 2010.[53] The United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in the occupied Palestinian Territory requested that Hamas reconsider dissolving that NGO.[54]

In June 2013, as a result of pressure from Egypt, Hamas deployed a 600-strong force to prevent rocket fire into Israel from Gaza. The following months showed a dramatic decline in the number of rockets fired at Israel.[55] in February 2014, however, Hamas removed most of the anti-rocket force it had deployed to prevent cross-border attacks on Israel. This move by Hamas is likely to have been interpreted as a green light to fire on Israel by the various other terror groups in Gaza,[56] such as the Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine, which carried out in excess of 60 rocket attacks on southern Israel, on March 12, 2014 alone.[57] In the wake of this incident of rocket-fire into Israel, and the many other incidents that followed, Israel warned that it might invade Gaza if the attacks did not cease.[58]

As further rocket attacks continued, Israel took action in the summer of 2014 by carrying out a temporary invasion of the Gaza Strip, during which more than 800 Hamas members were killed by the IDF (according to Israel's ITIC organization)[59] – note that casualty statistics in Gaza-Israeli conflicts are commonly up for debate and controversy (the latter analyses the casualty figures from the 2008–09 Gaza conflict). This came as a major blow to Hamas, and to their support in the Gaza Strip. The emergence of a recent faction of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (yet to be officially confirmed) within the Strip has also added security-concerns amongst Hamas officials, following the unsuccessful defence of the Strip against Israel's Operation Protective Edge. On May 31, 2015, the Islamic State Group offshoot, also calling itself the "Sheikh Omar Hadid Brigade",[60] claimed responsibility for the assassination of a high ranking Hamas commander, whose vehicle was blown up when an on-board bomb was detonated.[61]

The General Security Service, formally part of the Hamas political party, operates akin to a governmental body within Gaza. Under the direct oversight of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, it conducts extensive surveillance on Palestinians, compiling files on various individuals including journalists and government critics. This secret police force relies on a network of informants and employs tactics such as censorship and surveillance to maintain control. Before the 2023 conflict with Israel, the unit reportedly had a monthly budget of $120,000 and consisted of 856 personnel, including more than 160 individuals paid to spread Hamas propaganda and conduct online attacks against opponents.[62]

Other powerful internal security bodies in Gaza include Military Intelligence, which focuses on Israel, and the Internal Security Service, an arm of the Interior Ministry.[62]

Finance and economics

Upon taking power, Hamas announced they would refuse to honour past international agreements between the Palestinian government and Israel. As a result, the United States and the EU cut off aid to the Gaza Strip, and Israel and the Middle East Quartet implemented punitive economic measures against the Gaza Strip.[63] They view the group as a terrorist organization, and have pressured Hamas to recognize Israel, renounce violence, and make good on past agreements. Prior to disengagement, 120,000 Palestinians from Gaza were employed in Israel or in joint projects. After the Israeli withdrawal, the gross domestic product of the Gaza Strip declined. Israeli enterprises shut down, work relationships were severed and job opportunities in Israel dried up.[64]

Following Hamas' takeover in 2007, key international powers, including the EU, US and Israel showed public support for the new Fatah administration without Hamas. The EU and US normalized the tie to the Palestinian National Authority and resumed direct aid. Israel announced it would return frozen tax revenue of about US$800m to the new Fatah administration.[65] Israel also imposed a naval blockade of the Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip, which ensured Mediterranean imports of goods into the Strip did not include any sort of weaponry. The naval policy was stopped, and then was re-initiated in early 2014, when an arms shipment was seized by the IDF.[66] The move disabled Hamas from making further investments in weapon-trade with Iran, and other Iranian backed groups such as Hezbollah in Lebanon.[67]

Despite the active blockade (which many claimed also restricted non-weapon related trade, such as food supply),[68] Hamas leader Mahmoud Zahar said, speaking in 2012, that Gaza's economic situation has improved and Gaza has become self-reliant "in several aspects except petroleum and electricity." Zahar said that Gaza's economic conditions are better than those in the West Bank.[69] However, such statements have been considered political propaganda by many, and could have been aimed towards diminishing the economic successes of the rival Fatah political party in the West Bank, at a time when tensions between the two parties became particularly intense.[70]

2012 fuel crisis

Gaza generally obtained its diesel fuel from Israel[71] but, in 2011, Hamas began buying cheaper fuel from Egypt, bringing it via a network of tunnels, and refused to buy it from Israel.[72]

In early 2012, due to internal economic disagreement between the Palestinian Authority and the Hamas Government in Gaza, decreased supplies from Egypt through tunnel smuggling, and Hamas' refusal to ship fuel via Israel, the Gaza Strip plunged into a fuel crisis, bringing increasingly long electricity shut downs and disruption of transportation. Egypt attempted to stop the use of tunnels for delivery of Egyptian fuel purchased by Palestinian authorities, and severely reduced supply through the tunnel network. As the crisis deepened, Hamas sought to equip the Rafah terminal between Egypt and Gaza for fuel transfer, and refused to accept fuel delivered via the Kerem Shalom crossing between Israel and Gaza.[73]

In mid-February, as the crisis escalated, Hamas rejected an Egyptian proposal to bring in fuel via the Kerem Shalom Crossing between Israel and Gaza to reactivate Gaza's only power plant. Ahmed Abu Al-Amreen of the Hamas-run Energy Authority refused it on the grounds that the crossing is operated by Israel and Hamas' fierce opposition to the existence of Israel. Egypt cannot ship diesel fuel to Gaza directly through the Rafah crossing point, because it is limited to the movement of individuals.[72]

In early March, the head of Gaza's energy authority stated that Egypt wanted to transfer energy via the Kerem Shalom Crossing, but he personally refused it to go through the "Zionist entity" (Israel) and insisted that Egypt transfer the fuel through the Rafah Crossing, although this crossing is not equipped to handle the half-million liters needed each day.[74]

In late March, Hamas began offering carpools of Hamas state vehicles for people to get to work. Many Gazans began to wonder how these vehicles have fuel themselves, as diesel was completely unavailable in Gaza, ambulances could no longer be used, but Hamas government officials still had fuel for their own cars. Many Gazans said that Hamas confiscated the fuel it needed from petrol stations and used it exclusively for their own purposes.[75]

Egypt agreed to provide 600,000 liters of fuel to Gaza daily, but it had no way of delivering it that Hamas would agree to.[76]

In addition, Israel introduced a number of goods and vehicles into the Gaza Strip via the Kerem Shalom Crossing, as well as the normal diesel for hospitals. Israel also shipped 150,000 liters of diesel through the crossing, which was paid for by the Red Cross.[75]

In April 2012, the issue was resolved as certain amounts of fuel were supplied with the involvement of the Red Cross, after the Palestinian Authority and Hamas reached a deal. Fuel was finally transferred via the Israeli Kerem Shalom Crossing.[77]

Economic protests

In March 2019, there were a series of economic protests against Hamas in response to tax hikes due to the Israeli-Egyptian blockade of the Gaza Strip and financial pressure from the Palestinian Authority. Protesters used the slogan "We want to live". Hamas responded by arresting and beating people (including journalists and human rights employees), as well as by raiding homes.[78] In July and August 2023, thousands of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip took to the streets to protest chronic power outages, poor economic conditions in the territory, and Hamas's taxation of stipends to the poor paid by Qatar. The 2023 rallies, organized by a grassroots online movement called "Alvirus Alsakher" (The mocking virus), were a rare public display of discontent against the ruling Hamas government. Hamas bars most demonstrations and public displays of discontent.[79][80] Hamas police attacked and detained journalists attempting to cover the protests,[80] and at least one protestor was killed.[81]

International aid

Israeli cooperation

In January and February 2011, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) conducted an assessment of the effects of the measures to ease the access restrictions.[82] They concluded that they did not result in a significant improvement in people's livelihoods.[82] They found that the "pivotal nature of the remaining restrictions" and the effects of three years of strict blockade prevented a significant improvement in livelihoods and called on Israel to fully abolish the blockade including removing restrictions on the import of construction materials and the exports of goods, and to lift the general ban on the movement of people between Gaza and the West Bank via Israel in order to comply with what they described as international humanitarian and human rights law obligations.[82]

International visits

Qatari Emir Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani became the first foreign leader to visit the enclave since Hamas' takeover.[83] On 16 November 2012, following the death of Ahmed Jabril, Egyptian prime minister Hisham Qandil visited the enclave, leading to a brief ceasefire offer by Israel.[84] Tunisia's Foreign Minister Rafik Abdessalem[85] and Turkey's Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu visited Gaza in November 2012 as well.

Current budget

Most of the Gaza Strip administration funding comes from outside as aid, with a large portion delivered by UN organizations directly to education and food supply. Most of the Gaza GDP of $700 million comes as foreign humanitarian and direct economic support. Of those funds, the major part is supported by the U.S. and the European Union. Portions of the direct economic support have been provided by the Arab League, though it largely has not provided funds according to schedule. Among other alleged sources of Gaza administration budget is Iran.

A diplomatic source told Reuters that Iran had funded Hamas in the past with up to $300 million per year, but the flow of money had not been regular in 2011. "Payment has been in suspension since August", said the source.[86] The government of President Bashar al-Assad in Syria had been a stalwart ally and a conduit for Iranian money. But due to sectarian considerations following the revolt in Syria, Hamas decided to shut its political bureau in Damascus. Hamas' break with Syria has meant a sharp cut in the financing it received from Iran. In response, Hamas has raised taxes and fees considerably. Setting up its own lavish civil administration in Gaza that issues papers, licenses, insurance and numerous other permissions — and always for a tax or a fee.[51]

In January 2012, some diplomatic sources have said that Turkey promised to provide Haniyeh's Gaza Strip administration with $300 million to support its annual budget.[86]

In April 2012, the Hamas government in Gaza approved its budget for 2012, which was up 25% year-on-year over 2011 budget, indicating that donors, including Iran, benefactors in the Islamic world and Palestinian expatriates, are still heavily funding the movement.[87] Chief of Gaza's parliament's budget committee Jamal Nassar said the 2012 budget is $769 million, compared to $630 million in 2011.[87]

According to OpEd columnist Thomas Friedman of The New York Times, Gaza has been woefully mismanaged by Hamas: Gaza is pumping all its drinking water from its coastal aquifer at triple its renewable rate of recharge and, as a result, saltwater is seeping in. In 2013, the United Nations said that there would be no potable water left in Gaza's main aquifer by 2016. Gaza has no big desalination plant and lacks the electricity to run it anyway.[88]

See also

References

- ^ "Hamas' Gaza chief begins regional tour, to meet Ahmadinejad, Gulf leaders". Al Arabiya News. 30 January 2012. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ Avnery, Uri (14 April 2011). "Israel Must Recognize Hamas' Government in Gaza". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ "Hamas delivers free meals to Gaza's poor". aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2019-10-19. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ^ "The Palestinians try to reconcile". The Economist. 5 October 2017.

- ^ "Hamas command in north Gaza destroyed, Israel says". BBC. 2024-01-06. Retrieved 2024-03-11.

- ^ Burke, Jason (2024-01-30). "Hamas regroups in northern Gaza to prepare new offensive". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-03-11.

- ^ "Israel moves deeper into Rafah and fights Hamas militants regrouping in northern Gaza". AP News. 2024-05-12. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ Ebrahim, Nadeen (2024-05-13). "Israel's return to areas of Gaza it said were clear of Hamas raises doubts about its military strategy". CNN. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ "Big Hamas win in Gaza's election". BBC. 2005-01-28. Archived from the original on 2021-09-24. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ^ "Hamas battles for control of Gaza". The Guardian. 16 June 2007. Archived from the original on 2022-06-30. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

- ^ a b c "Hamas controls Gaza, says it will stay in power". CNN. Archived from the original on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ a b "Salafist ideological challenge to Hamas in Gaza". BBC News. 2011-05-13. Archived from the original on 2022-08-25. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ a b "Hamas police clash with Salafists in Gaza". News24. Archived from the original on 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ^ "Palestinian unity government sworn in by Mahmoud Abbas". BBC. 2 June 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "What's delaying Palestinian elections?". Al-Monitor. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Boudreaux, Richard (2007-01-07). "Abbas outlaws Hamas's paramilitary Executive Force". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2007-01-17. Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- ^ "The Palestinian National Unity Government". February 24, 2007. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ Black, Ian; Tran, Mark (15 June 2007). "Hamas takes control of Gaza". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2010.

- ^ "President Abbas prepares to swear in unelected interim government". Ma'an News Agency. Jun 16, 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ a b Nidal al-Mughrabi (Jun 16, 2007). "Hundreds flee Hamas-run Gaza amid spillover fears (Page 3)". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2007-06-18. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ a b "Fatah militants storm rival-held government buildings". CNN. June 16, 2007. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ Nidal al-Mughrabi (2007-06-16). "Hundreds flee Hamas-run Gaza amid spillover fears (Page 1)". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2022-10-06. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ "Kluft vertieft sich weiter (German)". ORF. Archived from the original on 2009-01-23. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ a b "Hamas losing control over Strip". Jerusalem Post. 6 March 2010. Archived from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ "Gaza economic protests expose cracks in Hamas's rule". BBC News. 2019-03-18. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ^ "Hamas Condemned After a Violent Crackdown on Protests in Gaza". Time. 2019-03-21. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ^ "Report of possible Gaza independence stirs debate". english.alarabiya.net. 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ a b HurriyetDailyNews (10 September 2012). "Hamas announces cabinet reshuffle in Gaza". Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Alarabiya (16 May 2012). "Reshuffled Palestinian government in West Bank sworn in, angering Hamas". Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "What's behind Hamas' latest Cabinet reshuffle in Gaza?". Al-monitor.com. 27 October 2016. Archived from the original on 2021-02-11. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ Khoury, Jack (11 March 2017). "Hamas Reportedly Establishing New Gaza Administration, Casting Shadow on Palestinian Unity". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ "Hamas appoints new prime minister in Gaza". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 13 June 2021. Archived from the original on 2023-02-28. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ "Interactive Map: Israel's Operation in Gaza". ArcGIS StoryMaps. 2024-10-26. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "Israel army says Hamas command structure 'dismantled' in north Gaza". South China Morning Post. 2024-01-07. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ Kubovich, Yaniv (18 January 2024). "Hamas Begins Rehabilitating Militant Units in Northern Gaza the Israeli Army Declared Dismantled". Haaretz. Retrieved 19 January 2024.

- ^ Burke, Jason (2024-01-30). "Hamas regroups in northern Gaza to prepare new offensive". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ Pamuk, Humeyra; Lewis, Simon (1 November 2023). "US, others exploring options for future of Gaza after Hamas - Blinken". Reuters. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ Al-Mughrabi, Nidal; Williams, Dan; Georgy, Michael (December 27, 2023). Perry, Michael (ed.). "What is Egypt's Proposal for Gaza?". Reuters. Archived from the original on December 27, 2023. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ "Israel presents postwar plan about control of Gaza Strip | Arkansas Democrat Gazette". www.arkansasonline.com. 2024-02-24. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ Greene, Richard Allen (2024-02-23). "Netanyahu unveils plan for Gaza's future post-Hamas". CNN. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ "Israeli military gov't in Gaza would cost NIS 20 billion annually, require 5 divisions — report". 17 May 2024. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "Gallant said to warn ministers that military rule in Gaza would cost 'many lives'". 17 May 2024. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ Beaumont, Peter (2024-05-15). "Israel war cabinet split looms as defence minister demands post-war Gaza plan". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-10-27.

- ^ Levinson, Charles; Matthew Moore (June 14, 2007). "Abbas declares state of emergency in Gaza". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on June 18, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ^ "Abbas sacks Hamas-led government". BBC News. June 14, 2007. Archived from the original on July 14, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ^ Rasgon, Adam; Bergman, Ronen (May 13, 2024). "Secret Hamas Files Show How It Spied on Everyday Palestinians". The New York Times.

- ^ "The Palestinians try to reconcile". The Economist. 5 October 2017. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ "Mapping Palestinian Politics - Hamas - Gaza Leadership". ECFR. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "The composition of the elected political bureau of Hamas in the Gaza Strip (2021)" (PDF). Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "Israeli occupation's threats against Hamas officials reflect political impasse". Hamas. 25 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ a b Erlanger, Steven (December 13, 2012). "Hamas Gains Allure in Gaza, but Money Is a Problem". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2012.

- ^ "'PA bans journalists from reporting human rights abuses'". The Jerusalem Post - JPost.com. 8 June 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2011-12-19.

- ^ Brown, Nathan J. Gaza Five Years On: Hamas Settles In Archived 2013-09-04 at the Wayback Machine Carnegie Endowment, June 2012

- ^ Statement by Maxwell Gaylard, United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator in the occupied Palestinian Territory On the Dissolution of Sharek Youth Forum in the Gaza Strip Archived 2014-02-03 at the Wayback Machine 20 July 2011

- ^ Hamas deploys 600-strong force to prevent rocket fire at Israel Archived 2022-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Times of Israel, June 17, 2013

- ^ Sales, Ben (15 August 2014). "Worse than Hamas? Gaza's other terror groups". Times of Israel.

- ^ "Times of Israel March report". Archived from the original on 2022-11-23. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ Hamas has removed most of the 900-strong force it employs to prevent rocket fire into Israel from Gaza Archived 2021-12-18 at the Wayback Machine, Times of Israel, February 1, 2014

- ^ "ITIC estimates" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-16. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ "Israel National News – Yaakov Levi". Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ "IBTimes – Hamas commander killed by ISIS Gaza faction". Archived from the original on 2022-11-27. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ a b Rasgon, Adam; Bergman, Ronen (2024-05-13). "Secret Hamas Files Show How It Spied on Everyday Palestinians". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ "Donors Threaten Aid Cut After Hamas Win – by Emad Mekay". Antiwar.com. January 28, 2006. Archived from the original on March 9, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- ^ "Economics and the Gaza War". Tel Aviv University. 2014-09-01. Retrieved 2024-05-09.

- ^ "Key powers back Abbas government". BBC News. June 18, 2007. Archived from the original on May 3, 2022. Retrieved June 18, 2007.

- ^ "BBC – Israel halts 'weapons shipment from Iran'". Archived from the original on 2022-12-11. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ "Iran-Hezbollah-Hamas weapon trade axis". Archived from the original on 2023-02-14. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ "Gaza Report – UN" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-03-19. Retrieved 2017-06-28.

- ^ "Zahhar: Gaza more secure than West Bank". Maan. September 16, 2012. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- ^ "In Gaza, power cuts and rumours hamper reconciliation". Archived from the original on 2012-04-01. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-11. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Saud Abu Ramadan (18 February 2012). "Hamas Rejects Egypt Plan to Bring Gaza Fuel Via Israeli Crossing". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 2013-03-20. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

- ^ "Gaza electricity crisis". Maan News Agency. Archived from the original on 2013-06-02. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ محمد عنان (2012-03-04). "فلسطين الآن : مصر ستزود غزة بالوقود لشهر والطاقة تبحث البدائل". Paltimes.net. Archived from the original on 2014-08-06. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- ^ a b "Google Translate". google.com. Archived from the original on 2015-06-04. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- ^ "فلسطين الآن : نجيدة لـ"فلسطين الآن": مصر ستزود غزة بـ600 ألف لتر وقود يوميا". Paltimes.net. 2012-02-18. Archived from the original on 2014-08-06. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- ^ "Fuel tankers arrive in Gaza". Maan News Agency. Archived from the original on 2013-06-02. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ "Gaza economic protests expose cracks in Hamas's rule". 2019-03-18. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ "Thousands take to streets in Gaza in rare public display of discontent with Hamas". Associated Press. 2023-07-30. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ a b Kingsley, Patrick (2023-08-07). "Gaza Protests Struggle to Gain Traction as Police Crack Down". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2023-08-07. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ Adam, Ali (2023-08-06). "Despite Hamas' crackdown, Gaza protests continue in rare defiance". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 9 November 2023.

- ^ a b c "Easing the blockade – Assessing the humanitarian impact on the population of the Gaza Strip" (PDF). UNITED NATIONS Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory. March 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Qatar emir in landmark trip to Gaza". Financial Times. 23 October 2012. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Matt Bradley in Gaza City and Sam Dagher in Cairo (17 November 2012). "Egyptian Stance Feeds Hopes in Gaza – WSJ". WSJ. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Tunisian foreign minister to visit Gaza". The Jerusalem Post - JPost.com. 8 June 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-11-18. Retrieved 2012-11-17.

- ^ a b "Hamas’ Gaza chief begins regional tour, to meet Ahmadinejad, Gulf leaders". Archived 2012-04-01 at the Wayback Machine "The head of the Hamas government in Gaza, Ismail Haniyeh, arrived in Qatar on Monday, beginning a regional tour that is also expected to take him to Kuwait, Bahrain and Iran."

- ^ a b "Iran, benefactors boost Hamas' 2012 budget". english.alarabiya.net. 2 April 2012. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (February 8, 2014). "Whose Garbage Is This Anyway?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

External links

- Pelham, Nicolas (2011) Gaza's Tunnel Complex, Middle East Research and Information Project