Ham House

| Ham House | |

|---|---|

Ham House in 2016, with Coade stone statue of Father Thames, by John Bacon the elder, in the foreground | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Stuart |

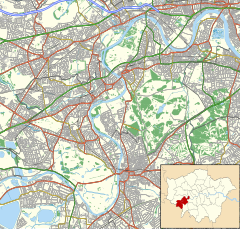

| Town or city | Ham, London |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°26′39″N 00°18′51″W / 51.44417°N 0.31417°W |

| Completed | 1610 |

| Client | Sir Thomas Vavasour |

| Owner | National Trust |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | William Samwell |

| Other information | |

| Parking | Ham Street |

| Website | |

| www | |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 10 January 1950 |

| Reference no. | 1080832 |

Ham House is a 17th-century house set in formal gardens on the bank of the River Thames in Ham, south of Richmond in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. The original house was completed in 1610 by Thomas Vavasour, an Elizabethan courtier and Knight Marshal to James I. It was then leased, and later bought, by William Murray, a close friend and supporter of Charles I. The English Civil War saw the house and much of the estate sequestrated, but Murray's wife Catherine regained them on payment of a fine. During the Protectorate his daughter Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart on her father's death in 1655, successfully navigated the prevailing anti-royalist sentiment and retained control of the estate.

The house achieved its greatest period of prominence following Elizabeth's second marriage—to John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale, in 1672. The Lauderdales held important roles at the court of the restored Charles II, the Duke being a member of the Cabal ministry and holder of major positions in Scotland, while the Duchess exercised significant social and political influence. They began an ambitious program of development and embellishment at Ham. The house was almost doubled in size and equipped with private apartments for the Duke and Duchess, as well as princely accommodation suites for visitors. The house was furnished to the highest standards of courtly taste and decorated with "a lavishness which transcended even what was fitting to their exalted rank".[1] The Lauderdales accumulated notable collections of paintings, tapestries and furniture, and redesigned the gardens and grounds to reflect their status and that of their guests.

After the Duchess's death, the property passed through the line of her descendants. Occasionally, major alterations were made to the house, such as the reconstruction undertaken by Lionel Tollemache, 4th Earl of Dysart, in the 1730s. For the most part, later generations of owners focused on the preservation of the house and its collections. The family did not retain the high position at court held by the Lauderdales under Charles II, and a strain of family eccentricity and reserve saw the fifth Earl refuse a request from King George III to visit Ham. On the death of the 9th Earl – the last Earl to live at Ham – in 1935, the house passed to his second cousin, Lyonel; he and his son, Major (Cecil) Lyonel Tollemache, donated it to the National Trust in 1948. During the second half of the 20th century the house and gardens were opened to the public, and were extensively restored and researched. The property has become a popular filming location for cinema and television productions, which make use of its period interiors and gardens.

The house is built of red brick, and was originally constructed to a traditional Elizabethan era H-plan; the southern, garden frontage was infilled during the Lauderdales' rebuilding. The architect of Vavasour's house is unknown although drawings by Robert Smythson and his son John exist. The Lauderdales first consulted William Bruce, a cousin of the Duchess, but ultimately employed William Samwell to undertake their rebuilding. Ham retains many original Jacobean and Caroline features and furnishings, most in an unusually fine condition, and is a "rare survival of 17th-century luxury and taste".[2] The house is a Grade I listed building and received museum accreditation from Arts Council England in 2015. Its park and formal gardens are listed at Grade II*. Bridget Cherry, in the revised London: South Pevsner published in 2002, acknowledged that the exterior of Ham was "not as attractive as other houses of this period", but noted the interior's "high architectural and decorative interest".[3] The critic John Julius Norwich described the house as a "time machine – enclosing one in the elegant, opulent world of van Dyck and Lely".[4]

The builders

[edit]Early years

[edit]

In the early 17th century the manors of Ham and Petersham were bestowed by James I on his son, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales.[5] The original construction of Ham House was completed in 1610 by Sir Thomas Vavasour, Knight Marshal to James I.[6] The Thames-side location was ideal for Vavasour, allowing him to move between the palaces at Richmond, Hampton, London and Windsor as his court role required.[7][6] It originally comprised an H-plan[a] layout consisting of nine bays and three storeys,[6] as shown in a 1649 miniature by Alexander Marshal,[10] but the lack of estate documentation makes it impossible to verify the names of persons involved in the design and construction of the house.[11] Robert Smythson's survey drawing of the house and gardens is a key record of the early structure.[12] Prince Henry died in 1612, and the lands passed to James's second son, Charles, several years before his coronation in 1625.[5] After Vavasour's death in 1620, the house was granted to John Ramsay, 1st Earl of Holderness, until he died in 1626.[6]

William Murray, 1st Earl of Dysart (1643–55)

[edit]In 1626, Ham House was leased to William Murray, courtier, a close childhood friend and alleged whipping boy of Charles I.[13] Murray's initial lease was for 39 years and, in 1631, a further 14 years were added.[14] When Gregory Cole, a neighbouring landowner, had to sell his property in Petersham as part of the enclosure of Richmond Park in 1637, he made over the remaining leases on his land to Murray.[13] Shortly afterwards William and his wife Katherine (or Catherine) engaged the services of skilled craftsmen, including the artist Francis Cleyn[15] and the painter Matthew Goodrich (or Goodricke),[16] to begin improvements on the house as befitting a Lord of the Manors of Ham and Petersham. He extended the Great Hall and added an arch that leads to the ornate cantilever staircase to create a processional route for guests as they approached the dining room on the first floor.[17] He remodelled the Long Gallery and added the adjoining Green Closet that was influenced by Charles I's own "Cabbonett Room" at Whitehall Palace, to which Murray had donated two pieces.[18] As part of the Whitehall Group, Murray would have been in touch with the latest tastes in art and architecture at court.[13]

In 1640 William was also granted a lease on the nearby Manor of Canbury, now in Kingston upon Thames, but in the run-up to civil war in 1641 he signed over the house to Katherine and his four daughters, appointing trustees to safeguard the estate for them.[19] The principal of these was Thomas Bruce, 1st Earl of Elgin, a relative of his wife and an important Scottish Presbyterian, Parliamentarian supporter and ally of the Puritan party in London.[20] Murray was raised to the peerage as Earl of Dysart in 1643, although his elevation appears not to have been confirmed at that time.[b] As a Scottish title, the earldom could be inherited by daughters, as well as by sons.[22]

Shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War, the house and estates were sequestrated,[23] but persistent appeals by Katherine regained them in 1646 on payment of a £500 fine.[24][25] Katherine skilfully defended her ownership of the house throughout the Civil War and Commonwealth, and it remained in the family's possession despite Murray's close ties with the Royalist cause.[26] Katherine died at Ham on 18 July 1649 (Charles I had been executed on 30 January of the same year).[26] The Parliamentarians sold off much of the Royal Estate, including the Manors of Ham and Petersham. These, including Ham House, were bought for £1,131.18s on 13 May 1650 by William Adams, the steward acting on behalf of Murray's eldest daughter, Elizabeth and her husband Sir Lionel Tollemache, 3rd Baronet of Helmingham Hall, Suffolk.[27] Ham House became Elizabeth and Lionel's primary residence, as Murray was in exile abroad, predominantly in France.[28][29]

Elizabeth, Countess of Dysart (1655–98) and Sir Lionel Tollemache Bt. (1640–69)

[edit]Elizabeth and Lionel Tollemache were married in 1648.[30] He was from a family of Royalists who had estates in Suffolk, Northamptonshire and London, and they celebrated their union at Ham with a display of arms that can be seen in the spandrels of the arch above the main entrance to the house: on the left an earl's coronet above the Tollemache horse's head and on the right the Tollemache argent a fret sable quartering Murray.[31]

When her father died in 1655 Elizabeth became the 2nd Countess of Dysart in her own right, but at that time during the Interregnum the title would have held little prestige.[31] Of far more interest to the Protectorate authorities was the matter of Elizabeth's allegiance. Her parents' activities during the Civil War had raised suspicion among both Royalists and Parliamentarians, and similar speculation attached to Elizabeth, which was heightened when she began a close relationship with Oliver Cromwell in the early 1650s.[32] Her family and connections provided the perfect cover for an agent, especially a double agent, and her movements were closely monitored by both Royalist and Parliamentarian spies.[33]

Between 1649 and 1661, Elizabeth bore eleven children, five of whom survived to adulthood; Lionel, Thomas, William, Elizabeth, and Catherine.[34] Elizabeth and Lionel made few substantial changes to the house during this busy time.[31] On the Restoration in 1660, Charles II rewarded Elizabeth with a pension of £800 for life[35] and, while many of the Parliamentarian sales of Royal lands were put aside, Elizabeth retained the titles to the Manors of Ham and Petersham. In addition, in about 1665, following William's death, Lionel was granted freehold of 75 acres (30 ha; 0.117 sq mi) of land in Ham and Petersham including that surrounding the house and a 61-year lease of 289 acres (117 ha; 0.452 sq mi) of demesne lands.[36] The grant was made in trust to Robert Murray for the daughters of the, then, late Earl of Dysart, "in consideration of the service done by the late Earl of Dysart and his Daughter, and of the losses sustained by them by the enclosure of the New Park".[36][37] Lionel died in 1669, leaving his Ham and Petersham estate to Elizabeth along with Framsden Hall in Suffolk, which had been her jointure on their marriage.[38]

Elizabeth and John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale (1645–82)

[edit]

Elizabeth may have become acquainted with John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale at some time in the 1640s, when he was one of the Scottish Commissioners on the Committee of Both Kingdoms who petitioned for her father's release on charges of treason in 1646.[39][40] She felt sufficient gratitude towards him to claim in later years that she appealed to Cromwell to show clemency following his capture after the Battle of Worcester, a gesture Maitland repaid in his will when he left her £1,500 in gold for "preserving my life when I was a prisoner in the year 1651".[41] They became much closer following the death of her husband and he began visiting Ham regularly.[42] Already a favourite of the King, he was appointed High Commissioner for Scotland in August 1669 which, on top of his political influence as Secretary of State and participation in Charles's Cabal ministry, made him one of the most powerful men in the country.[43] In 1671 Lauderdale was granted by Letters patent full freehold rights to the Manors of Ham and Petersham and the 289 acres of leased land. In 1672 Elizabeth and Lauderdale were married, and soon afterwards he was created Duke of Lauderdale and Knight of the Garter.[44] With Lauderdale's part in the Cabal Ministry, the family remained close to the heart of court intrigue.[45]

As Duchess and consort to a very political Duke, Elizabeth had risen to the peak of Restoration society where she could exercise her many talents and interests. Image was paramount and the Lauderdales began a programme of aggrandisement of their properties – Elizabeth consulted her cousin, William Bruce,[3] and Maitland commissioned William Samwell, respectively amateur and professional architects.[c][7] Ham was extended on the south front with an enfilade of rooms created each side of a central axis around a new downstairs Dining Room.[47] Most grand houses at that time had apartments laid out in this way, comprising a suite of rooms approached one through the other. The original plan was to create the Duchess's apartments to the left (east) and the Duke's to the right,[48] she having two closets for privacy and entertainment and he having a staircase connecting his bedroom to the library above, but Elizabeth appears to have changed her mind while the rooms were being built and eventually each came to have a bedchamber within the other's apartment. This alteration may have been due to the installation of a bathroom downstairs which had to be near the kitchen (the source of hot water) in the basement at the Duke's end of the house. Despite the swap of bedchambers, she retained her original closets at the east side of the house.[49]

Closets formed an exclusive and very private end to the sequence into which only the most important guests were invited.[50] Visitors knew that they would only progress through the rooms according to their rank or significance in society: being entertained in one of Elizabeth's closets would have been an honour.[51] Her White Closet was designed for entertaining and had a private door opening onto the Cherry Garden. It was decorated in the most advanced tastes of the day[48] and according to the 1679 inventory that it had "one Indian furnace for tee garnish'd wt silver",[52] a luxury at a time when tea was only beginning to be drunk outside of exclusive royal residences. For this reason, too Elizabeth kept her tea secure in a "Japan box" in her adjoining Private Closet.[53]

Upstairs the existing State Apartments (Great Dining Room, North Drawing Room and Long Gallery) were extended with the addition of a State Bedroom apartment.[54] The bedchamber itself was being referred to as "the Queen's Bedchamber" in 1674 which suggests that Queen Catherine of Braganza, a friend of Elizabeth's, had occupied it at least once.[51] This was the most important room in the house and the focal point towards which one progressed on the first floor.[55] Another benefit of transforming the house from single to double-pile – a "pile" is a row of rooms, single-pile houses have only one row while double-pile houses are two rows deep, often with a corridor between the rows[56] – had been that it allowed the creation of hidden passages and staircases for servants who could now enter rooms via discreet jib doors rather than by moving through one room to get to another.[57] Michael Wilson notes the "positive warren" of such passages at Ham.[58]

The eldest daughter of Elizabeth and Lionel, also named Elizabeth (1659–1735), married Archibald Campbell, 1st Duke of Argyll in Edinburgh in 1678. Their first child, John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll, was born at Ham House in 1680;[59] their second son, Archibald Campbell, 3rd Duke of Argyll was born there a few years later.[60]

The glorious years for the Lauderdales began to wane in 1680 when the Duke had a stroke and his influence declined.[61] On his death in 1682 he left the Ham and Petersham property to Elizabeth, thereby securing the estate for the Tollemache dynasty.[60] However, Elizabeth also inherited her husband's debts including mortgages on his former properties in England and Scotland and her latter years were marred by a financial dispute with her brother-in-law, Charles Maitland, 3rd Earl of Lauderdale.[60] Even the intervention of the newly crowned James II failed to reconcile them and the matter was finally settled in her favour in the Scottish courts in 1688.[62] Although this may have suppressed Elizabeth's lavish lifestyle, she went on to make further alterations to the house at Ham, opening the Hall ceiling and creating the Round Gallery in about 1690.[62] As she got older her movements became restricted by gout and she rarely went upstairs, living mainly in what had been the Duke's apartments, but her intellect remained and she liked to be kept informed about events at court and in politics.[62] Elizabeth Maitland continued to live at Ham House until her death in 1698 at the age of 72.[63]

Architecture

[edit]

Ham House is a brick building of three storeys and nine bays, with a hip roof and ashlar dressings, representing two distinctively different architectural styles and periods.[48] Michael Wilson, referencing Ham in his work, The English Country House and its furnishings, considers the later 17th century as the finest period of English brick building.[64] The first phase is the original main house facing north-east to the river Thames, built in 1610 in the early Jacobean English renaissance style on a traditional H-plan for Thomas Vavasour, Knight Marshal at the court of James I.[3] Simon Jenkins, in his study, England's Thousand Best Houses, records that the original entrance had a tower over the porch and flanking, projecting turrets, which were removed in subsequent reconstruction, and suggests that Vavasour's original house may have been of an E-plan type.[65] John Julius Norwich also notes the original configuration of the north front, which he considers "forbidding", and the "damson-coloured" brickwork.[66] Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner, in the London: South volume of the Buildings of England series, record the "not specially impressive" nature of the remaining doorway but are clear that Ham was built to an H-plan.[67] The architect of Vavasour's house is not known although survey drawings by Robert and John Smythson exist.[68]

The second phase of reconstruction is the ambitious expansion to the south or garden side of the original house by the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale in 1672 to display their high status in the court of King Charles II.[69] They infilled the space between the southern wings of the H-plan building, almost doubling the volume of the house.[70] Jenkins considers the Lauderdales' remodelling one of the earliest examples in England of the creation of a suite of state rooms for the accommodation and entertainment of royalty.[65] Although the Lauderdales initially consulted William Bruce, the architect ultimately employed to undertake the reconstruction of their south front was William Samwell. Bruce did design the gates fronting the Thames on the north facade.[3]

The northern façade retains the Jacobean arched loggias[71] on either side of the front door and also includes an array of marble and lead busts, which continue into the flanking courtyard walls.[72] The southern Caroline façade is loosely based on a classical style introduced from the continent by the architect Inigo Jones (1573–1652).[73] At the time the Lauderdales' remodelling project was considered impressive,[74] the façades giving the impression of two separate houses, while the interior blends them harmoniously. Roger North, a contemporary aristocrat, amateur architect and critic, described the remodelling in his treatise, Of Building, and considered it as the best work he had seen.[48] The renovation also included a very early installation of sash windows, a French invention[75] which were refined with weights and pulleys in England.[76] The east front of the house retains many of its 17th century windows, as well as the door to the Great Staircase and the door from the Duchess's private apartments to the cherry garden.[77] The west front of the house contains a mixture of 17th and 18th century windows and has long served as the service entrance to the house. Structures such as the bake house, still house, bath house, dairy and ice house were located to the west of the house, although some no longer survive.[78]

Listing designations

[edit]Historic England is an organisation dedicated to the protection of England's historic environment and is responsible for the listing of buildings. There are three available designations: Grade I, Grade II* and Grade II, with the first being applied to buildings of "exceptional interest".[79] The house is a Grade I listed building.[80] Ham was also given Accredited Museum status in 2015, having demonstrated compliance with UK industry standards for museums and galleries.[81] The Park and Garden has a Grade II* listing.[82] A number of the surrounding features have a Grade II listing: the Forecourt,[83] the entrance gates and railings,[84] the Garden walls and gatepiers to the south,[85] the Orangery (now used as a tea room),[86] the Ice House,[87] the service yard to the west of the house[88] and the Gatehouse.[89]

Plan

[edit]

Interiors and collections

[edit]Introduction

[edit]Ham House is unusual in retaining much of its original 17th-century interior decoration, offering a rare experience of the style of the courts of Charles I and Charles II.[90] Ham House's rooms display collections of 17th-century paintings, portraits and miniatures, in addition to cabinets, tapestries and furniture amassed and retained by generations of the Murray and Tollemache families. Geoffrey Beard, in his study, The National Trust Book of English Furniture, noted the extraordinarily high quality of the Lauderdales' furnishing of the house, undertaken with "a lavishness which transcended even what was fitting to their exalted rank".[1] Bridget Cherry, in the London: South volume of the Pevsner Architectural Guides suggested that, while the exterior of Ham was "not as attractive as other houses of this period", the "high architectural and decorative interest" of its interior should be recognised.[3] John Julius Norwich considered the interiors, a "time machine – enclosing one in the elegant, opulent world of van Dyck and Lely".[4]

Great Hall

[edit]

This room forms part of the original 1610 construction and is off-set from the centre, in the English Gothic and Tudor tradition.[48] During this time, the hall may have been used for both dining and entertainment.[91] The distinctive black and white marble chequerboard flooring is also believed to date from the original construction.[70] By the early 18th century the room had been expanded upwards by opening the ceiling to the room above, now known as the Round Gallery. The room contains a number of large and notable paintings.

- Charlotte Walpole, Countess of Dysart (1738–1789), by Sir Joshua Reynolds, was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1775.[92]

- John Constable, a family friend, was commissioned to make copies of two family portraits: Anna Maria Lewis, Countess of Dysart (1745–1804) as Miranda, painted in 1823 after Joshua Reynolds[93] and Lady Louisa Tollemache, Countess of Dysart (1745–1840), painted in 1823–25 after John Hoppner.[94]

- Hanging side by side are John Vanderbank's portraits of Lionel Tollemache, 4th Earl of Dysart (1708–1770) painted in 1730[95] and of his wife Lady Grace Carteret, Countess of Dysart (1713–1755), signed and dated 1737.[96]

Chapel

[edit]

Formerly the family's sitting room, this room was converted to a chapel during the major renovations of the 1670s.[97] It was decorated with crimson velvet and damask wall hangings, which were changed to black velvet upon the Duke's death in 1682.[98] While designed for Protestant worship, the chapel was used in the late 19th century by the wife of the 8th Earl for Roman Catholic services.[99] The sumptuous and rare 17th-century textiles require that the light levels remain low, in order to minimise damage.[100]

Great Staircase

[edit]

The Great Staircase, described by the historian Christopher Rowell as "remarkable" and "apparently without a close parallel in the British Isles",[101] was created for William Murray at the east end of the Great Hall in 1638–39 as part of a series of improvements to the house which reflected his rising status at Court.[102] An ornately carved archway marks the entrance from the Great Hall to the stairs, which were designed as a grand processional route giving access to the State Apartments on the first floor.[73] The cantilever staircase rises over three floors above a square stairwell. The balustrade is composed of boldly hand-carved pierced wooden panels depicting trophies of war.[103] Each panel is different, with varying images on each face of arms and armour, including a set of horse armour. The wide range of arms includes field guns with cannonballs and barrels of gunpowder, swords, shields, quivers of arrows and halberds. Dolphins, elephant heads, dragons and other fantastical creatures also appear on the dado panelling, together with military drums and trumpets. The martial theme of these panels is interspersed with drops of relief carvings of bay leaves, richly carved newel posts topped with baskets of fruit[103] designed to carry candles or candelabra, and miniature swags decorating the outer string. Originally gilded and grained to resemble walnut,[104] in the 19th century the balustrade and other woodwork were picked out in bronze, traces of which survive. According to Rowell, "There is no other architectural wood carving on this scale and of such sophistication surviving from the late 1630s."[101]

A collection of 17th century copies of old master paintings in their original carved frames hangs on the staircase wall. Two were copied from originals in the collection of Charles I:[105] Venus with Mercury and Cupid (The School of Love) by Correggio at the base of the stairs (the original in the National Gallery, London),[106] while on the first floor landing there is a copy of The Venus Del Pardo (Venus and a Satyr) by Titian (the original in the Louvre, Paris).[107]

Round Gallery

[edit]Before the upward expansion of the Great Hall this room had served as the Great Dining Room, as created by William Murray in the 1630s.[108] The ornate white plasterwork ceiling was created by Joseph Kinsman,[103] master craftsman and member of the London Plasterers' Company.[109] Engaged by the Royal Works at Goldsmith's Hall, Whitehall and Somerset House, he was employed by William Murray at Ham House during the 1637 renovation and creation of the State Apartments.[103] The ceilings at Ham are the only surviving example of his work, showing the influence of Inigo Jones in their design of deep beams with rosettes at the intersections, enclosing geometric compartments.[103] The white plaster high relief oval swags of luscious fruit, flowers and ribbons, including the odd worm, contrasted with the elaborate frieze which was originally coloured blue and gold.[103]

Notable paintings include Peter Lely's final portrait of Elizabeth, painted c. 1680, and the earlier double portrait, John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale and Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart and Duchess of Lauderdale painted by Lely c. 1675.[110]

North Drawing Room

[edit]

After dinner in the adjacent dining room, guests would have retired to the North Drawing Room for conversation.[111] This room was decorated at the same time as the Great Dining Room, and was later hung with tapestries.[111] Kinsman continued his elaborate plasterwork in the white ceiling in this room.[103] Deep beams enclose rectangles bursting with individually crafted fruit and flowers. The hemispherical rosettes at the intersections are unusual, possibly unique.[112]

A notable piece of furniture in this room is the ivory cabinet: veneered in rippled ivory panels on the exterior and the interior, this large oak and cedar cabinet opens to reveal 14 drawers. An inner door conceals small drawers, further secret drawers and a compartment. It was recorded as being moved to the prestigious Queen's Bedchamber shortly after its appearance in the 1677 inventory[113] and is considered the most impressive piece of furniture designed or bought for the house (with the exception of the State Bed, which no longer exists).[114] The cabinet may have been made in the Northern Netherlands based on furniture inlaid in ivory brought back in 1644 by John Maurice, Prince of Nassau-Siegen, the former Governor of Dutch Brazil for his home in The Hague, now called the Mauritshuis.[113]

Also notable in the room are a vibrant set of tapestries. James I established the Mortlake Tapestry Works in 1619 just three miles from Ham House, from which the Lauderdales had purchased a set of tapestries showing the seasons incorporating gold thread for the Queen's Bedchamber.[115] While these are no longer at the house, the 4th Earl of Dysart acquired a set woven in Lambeth in 1699–1719 by the ex-Mortlake weaver Stephen de May, probably to the Mortlake design.[116] Altered to hang in the North Drawing Room, this set of The Seasons was originally commissioned by the 1st Lord Shelburne.[116] Tapestries were important in Europe for comfort in draughty manor houses and as status objects because of their expense. Sets with designs showing the seasons or months were popular and had a number of variations depicting appropriate seasonal activities[117] such as milking for April, ploughing and sowing for September, and wine-making for October.[118]

Long Gallery

[edit]

The Long Gallery was part of the original 1610 house, but was extensively redecorated in 1639 by William Murray. It has been used as an exercise space as well as a gallery to showcase portraits of family and important royal connections.[119] Notable paintings include:

- Sir John Maitland, 1st Baron Maitland of Thirlestane (1543–1595), aged 44 attributed to Adrian Vanson.[120] In late 2016 an X-ray revealed that underneath the main painting was another, unfinished portrait likely of Mary, Queen of Scots, dated 1589—two years after her execution. According to the National Trust, this painting "shows that portraits of the queen were being copied and presumably displayed in Scotland around the time of her execution, a highly contentious and potentially dangerous thing to be seen doing".[121]

- King Charles I (1600–1649) by Sir Anthony van Dyck and studio.[122] In recognition of their friendship this painting was given by Charles I to William Murray; a 1638–39 memorandum of pictures bought by the King from Van Dyck includes framed pictures, one of which is believed to be this portrait.[123]

- Colonel The Hon. John Russell (1620–1681) by John Michael Wright is signed and dated 1659.[124]

- Of the 15 portraits by Peter Lely in Ham House,[125] 11 are hung in the Long Gallery. These include Elizabeth Murray with a Black Servant, John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale (1616–1682) in Garter robes, and Thomas Clifford, 1st Baron Clifford of Chudleigh KG (1630–1673) in Garter robes.[126][127][128]

Picture frames at Ham House date from the 17th century and its Long Gallery portraits are a showcase of elaborately carved, gilded frames in the auricular style (literally 'of the ear').[129] Two frames date from the 1630s, Charles I and Henrietta Maria. Later frames, for instance on the portraits of Elizabeth Murray with a Black Servant[d] and Lady Margaret Murray, Lady Maynard are in a similar auricular style with straight sight edges. These frames, referred to as Sunderland frames, are distinguished by their irregular sight edges. They take their name from the 2nd Earl of Sunderland, who displayed many pictures at his estate Althorp framed in this style.[131] There are examples of Sunderland frames on the portraits of John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale (1616–1682) in Garter Robes[132] and Colonel The Hon. John Russell (1620–1681).[133]

This room also displays some notable furniture:

- Floral marquetry cabinet: Ham House has a number of tables and cabinets decorated with floral marquetry including this, the earliest inventoried example in England, dating from 1675.[134] The naturalistic representations of flowers and fruit are cut from contrasting woods such as ebony, walnut and stained fruitwood and laid onto the carcass. The woods and other materials were often dyed to create a greater range of colours and the green leaves on this piece are made from stained ivory or bone. This cabinet, as well as other tables and a mirror in the house, is attributed by the National Trust to Gerrit Jensen, who was the cabinet maker in ordinary to Catherine of Braganza.[135]

- Japanese lacquered cabinet: Japanese lacquered furniture was fashionable in the 17th century and this cabinet from 1650 remains in the Long Gallery where it has stood since then. Decorated with hills, trees and birds in raised gold and silver lacquer, the doors open on engraved brass hinges to reveal 10 drawers. The giltwood stand has four legs carved as elephant trunks topped with winged cherub busts.[136]

- Chinese lacquered chest: China was another Asian source of lacquered furniture in the 17th century. Decorated with watery landscapes and branches, this chest is lacquered in gold and red on a dark crimson ground. It was a standard form of storage chest for linens and other textiles.[115] The English stand c. 1730 is japanned, a technique developed by English and European craftsmen to approximate the hard, smooth and shiny surfaces of popular Asian lacquered goods.[137]

Green Closet

[edit]

Used for the display of miniature paintings and smaller-scale furniture, in contrast to the Long Gallery,[129] this room is a very rare survival of a room in the style of Charles I's court.[70] In the 1630s the Green Closet was specifically designed by William Murray to display miniatures and small paintings.[138] The ceiling paintings are tempera on paper, and represent some of Franz Cleyn's best surviving work.[139] Two preliminary drawings for the capricci of putti by Cleyn and an associate are held by the University of Southampton.[140]

Today it contains 87 items including Queen Elizabeth I (1533–1603) painted c. 1590 by Nicholas Hilliard,[141] and A Man Consumed by Flames painted c. 1610 by Isaac Oliver.[142]

Library

[edit]

The Library dates from the 1672–74 enlargement of the house. The architectural historian Mark Girouard considers it probably "the oldest country house library" still in existence.[143] Although some shelves were moved from what is now the Queen's Antechamber, most of the cedar fixed furniture, including the secretaire, was provided by Henry Harlow.[144] The Duke of Lauderdale added substantially to the contents: he was an avid reader and collector[50] (so much so that his Highgate house was said to be in danger of collapse due to the weight of his substantial book collection),[145] and he owed huge sums to booksellers when he died. Mark Purcell, in his 2017 study The Country House Library, notes that the probate inventory undertaken on the Duke's death estimated the value of his books at half of the total worth of the house's chattels.[146] Many volumes were sold at auctions between 1688 and 1692, in part due to the Duchess's money difficulties upon the Duke's death.[147]

Later members of the family rebuilt the collection, notably the 4th Earl who bought at the Harleian auction and elsewhere.[148] He acquired 12 books printed by William Caxton and many other incunabula;[149] in 1904 a visitor, William Younger Fletcher, described the library as containing books of greater value, in proportion to its size, than any other in Europe.[150] Most of the books were sold in 1938,[148] and the bulk of the remainder after the Second World War. A notable exception, a Book of Common Prayer from Whitehall Palace, is sometimes on display in the chapel.[151]

After the war Norman Norris, a Brighton book dealer, assembled a collection of books from a range of post-war country house sales. He bequeathed the collection to the National Trust and many eventually came to Ham, primarily those pre-dating the mid-18th century.[152] One, Jus Parliamentarium, which has the Dysart coat of arms on its cover, is from the Dysart collection. The ceiling and friezes in the room display a lively naturalism. Two globes with rare leather covers[153] (acquired in 1745 and 1746) and two fire screens (1743) are notable.[154]

Queen's Apartments

[edit]This suite of three rooms, now referred to as the Queen's Apartments, was created by the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale when the house was enlarged in 1673.[70] Intended for use by Catherine of Braganza,[e][155] they reflect the latest innovations from France, where royalty received important visitors in the State Bedchamber.[156] The rooms are decorated with increasing splendour, beginning with the relatively modest Antechamber, culminating in the small but richly gilded and decorated Queen's Closet.[157]

Antechamber

[edit]The first of the suite of rooms is the antechamber, where visitors would wait for an audience with the Queen. The ceiling of this waiting room is the first of the three ceilings by the plasterer Henry Wells.[158] A circular garland of leaves is thickly studded with small flowers, surrounded by four spandrels containing foliage and ribbons. The oak parquet floor, an innovation from France, continues through to the far side of the Queen's Bedchamber where it is then replaced with a more elaborate marquetry design where the State Bed would have stood. The blue velvet and damask wall hangings, installed during the period 1679–1683, are extremely rare survivals.[159]

Queen's Bedchamber

[edit]

This room, built on the central axis of the house, was designed for the reception of guests and visiting dignitaries who would have waited to be summoned from the Antechamber. The State Bed stood prominently on a raised dais at the east end of the room facing the door.[160] A balustrade separated the bed from the main area of the room where visitors may have gathered for their audience with the Queen. The bed was on an elaborate marquetry floor inlaid with the cipher and ducal coronet of the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale, their initials J, E and L entwined in cedar and walnut, a feature that repeats in the Queens's Closet.[161] The floor remains in excellent condition. This ceiling has the richest plaster decoration in the house, a large deep oval of bay leaves dotted with roses. These cluster more densely at the east end, above the area of the Queen's State Bed. The spandrels are also more decorative, acanthus leaves swirl to fill the panels, each corner hiding a grotesque figure among the foliage or bursting from the flowers.[162]

The bed had been removed by 1728[163] and the rooms were closed and rarely used, contributing to their excellent state of preservation. The change of use to a drawing room took place in the mid‑18th century with the lowering of the dais in line with the rest of the floor, and the purchase of new furniture and a set of William Bradshaw's popular early 18th century pastoral tapestries.[163] Woven in 1734–40 for Henry O'Brien, 8th Earl of Thomond, and purchased in 1742 for £184 on behalf of the 4th Earl of Dysart, the tapestries needed only slight alterations to fit three of the walls of his newly decorated drawing room. Bradshaw's signature can be seen on The Dance tapestry. Woven in Soho, London, the four wool and silk tapestries have narrow borders in the style of picture frames and are thought to incorporate several different images from works by the French painters Antoine Watteau, Nicolas Lancret and Jean-Baptiste Pater.[164]

Queen's Closet

[edit]The smallest, most intimate of the suite of rooms, the third and final room was designed for private use and could be closed off, away from the business of the State Bedchamber.[f] Rarely used and preserved largely intact, the decoration, textiles and furniture give a unique record of late 17th century interior decoration.[166] The marquetry floor incorporating the ducal coronet and cipher continues from the Bedchamber into the Closet. The ceiling painting of Ganymede and the Eagle is in the style of the Italian artist Antonio Verrio (1636–1707).[167] Framed by a plaster garland,[162] following the designs of the previous rooms, the richness of the effect is emphasised by gilding of the roses. Three ceiling paintings, again in the style of Verrio,[168] of cupids sprinkling flowers, are partly hidden from view above the alcove. The elaborate chimney piece, hearth and windowsill, again including the Lauderdale cipher and ducal coronet, are made from scagliola, possibly the earliest documented example of scagliola in this country.[162]

Private Closet

[edit]

This was the Duchess's most private and intimate room where she would read, write and entertain her closest family and friends.[169] The elaborate oil on plaster ceilings in both of the Duchess's closets are by Antonio Verrio. They are among his earliest commissions in England, and his earliest surviving work following his arrival from France in 1672.[167] As his reputation grew he was commissioned by royal and aristocratic clients for larger projects including for Charles II at Windsor Castle,[170] interiors for the Earl of Exeter at Burghley House[171] and for William III at Hampton Court.[172] The ceiling painting of The Penitent Magdalene Surrounded by Putti Holding Emblems of Time, Death and Eternity was completed around 1675.[173] The central figure floats above the room, circled by three putti carrying symbols of time (an hourglass), death (a skull), and eternity (a snake eating its own tail). Verrio linked the ceiling design to the room by enclosing it in a narrow painted grey marble surround, matching the marble fireplace.[174] The room also contains a portrait of Catherine Bruce, Mrs William Murray (d. 1649), by John Hoskins the Elder, a watercolour on vellum in an ebony travelling case, signed and dated 1638.[175]

White Closet

[edit]Adjoining the Private Closet and richly decorated, this room was used by the Duchess for relaxing and entertaining, its double glazed door leading out to the Cherry Garden.[176] The coved ceiling of this glamorous room, originally decorated with white silk hangings and marble effect walls,[177] emphasises the advanced taste of the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale in a room intended for their most important visitors.[50] Painted by Verrio[103] in oil on plaster in 1673/74, it is described by the art historians Peter Thornton and Maurice Tomlin as "decorated with one of the earliest examples of Baroque illusionism to have been executed in a domestic interior in this country".[178] Putti climb up over a trompe l'oeil balustrade to reach the figures of Divine Wisdom Presiding Over The Liberal Arts, represented by seven mainly female figures bearing the symbols of Verrio's version of the liberal arts.[174] The figure of Wisdom floats on clouds pointing to the all-seeing eye in the open sky above. Verrio linked the ceiling design to the room by enclosing it in a narrow painted red marble surround, matching the red marble fireplace,[176] as in the Private Closet. The heavily gilded coving includes medallions of the four Cardinal virtues. Notable collection items include:

- Ham House from the South (1675–79) by Hendrick Danckerts depicts a finely dressed couple (possibly the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale) in front of the south front and formal gardens,[179] and was set into the chimneypiece in the White Closet shortly after the building was completed.[180]

- Escritoire of kingwood oysterwork: this elegant oak scriptor (c. 1672–75) is veneered with South American kingwood using the oystering technique and features silver mounts. Made for the Duchess of Lauderdale, it is listed in the 1679 inventory of Ham House and is believed to have been made in London by a French or Dutch craftsman.[181] Kingwood was one of the most expensive woods used in furniture making in the 17th century.[182][183]

Marble Dining Room

[edit]

Since 1675 the walls of the Marble Dining Room have been decorated with leather panels.[184] Today visitors can see two distinct designs. The earlier design of 1675 complemented the original black and white marble floor, for which the room is named, with brightly coloured Flemish leather panels of fruits and flowers such as tulips and roses mixed with birds and butterflies on a white background. These had been embossed and some elements gilded, giving the room a sumptuous look.[185]

In 1756, the 4th Earl removed the marble floor and replaced it with a fine marquetry floor of tropical hardwoods.[148] He also commissioned John Hutton of London to make a new set of leather wall hangings with an embossed diaper rosette surrounded by four leaves.[148] The parts of the design which are now brown would originally have appeared to be gold, made by varnishing silver leaf in yellow.[186] The fashion for leather wall decoration spread from Spain and the Spanish Netherlands in the 17th century and was considered ideal for dining rooms as leather did not become impregnated with the odours of food like the fabric of a tapestry.[186] The Ham House inventory of 1655 indicates the "two parlers facing the river were hung with gilt leather."[187]

Withdrawing Room

[edit]

After dining in the adjacent Marble Dining Room, guests would retire to this space for entertainment and conversation.[188] It also served as an antechamber to the adjacent bedchamber.[188] Notable in this room is the ebony and tortoiseshell cabinet: this cabinet (c. 1650–1675) on a possibly 19th century stand features red tortoiseshell decoration on a somewhat austere ebonised pine exterior that does not prepare the viewer for the ornate interior. Two doors open to reveal multiple shallow drawers on either side of an architectural exterior, which then opens to a theatrical set framed by golden pillars and mirrors.[189] Known as the Antwerp cabinet,[190] it is embellished with ivory, pietra paesina (a type of naturally patterned limestone) and gilt bronze and brass.[191]

Duchess's Bedchamber

[edit]Originally the Duke's bedchamber,[49] it is believed it became the Duchess's bedchamber following the installation of the bathroom[49] which is accessed via the door to the left of the bed alcove. The ceiling above the bed in the alcove is painted in the style of Antonio Verrio and shows the partially clothed Flora Attended by Cupids floating above the tester of the four poster bed.[192] The monogram initials J, E and L (John, Elizabeth, Lauderdale) are entwined in each corner. Notable paintings include:

- Elizabeth Murray (1626–1698) painted by Peter Lely in 1648, the year of her marriage to Lionel Tollemache.[193]

- A set of four overdoor maritime paintings by Willem van de Velde the Younger, signed and dated 1673, including Calm: An English Frigate at Anchor Firing a Salute, which remain from the decoration scheme planned for the room's use as the Duke's bedchamber.[194]

Back Parlour

[edit]This was the room in which senior male staff would have eaten their meals and spent any free time.[149] Hanging in this room is: Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart (1626–1698), with her First Husband, Sir Lionel Tollemache (1624–1669), and her Sister, Margaret Murray, Lady Maynard (c. 1638–1682) painted c. 1648 by Joan Carlile,[195] a friend and neighbour to the Murrays.[196]

Garden and grounds

[edit]

The gardens and pleasure grounds at Ham cover approximately 12 hectares (30 acres). They follow an axial plan, with avenues originally leading east, west and south from the house. The fourth, northern, side of the estate fronts the River Thames.[197] The listed avenues leading to the house from the A307 are formed by more than 250 trees stretching east from the house to the 19th-century Jacobethan gate house at Petersham, and south across the open expanse of Ham Common where it is flanked by a pair of more modest gatehouses.[3] A third avenue to the west no longer exists, and the view to and from the Thames completes the principal approaches to the house.[3] The gardens and grounds are listed Grade II* on Historic England's Register of Historic Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in England.[197] From the initial survey drawings produced by Robert Smythson and son in 1609,[68] it is clear that the garden design was considered as important as that of the house and that the two were intended to be in harmony.[198] The original design shows the house set within a range of walled gardens, each with different formal designs as well as an orchard and vegetable garden. Uncertainty remains as to how much of the original design was actually realised;[199] nevertheless, the plans illustrate the influence of the French formal garden of the time, with its emphasis on visual effects and perspectives.[200]

The 1671 plans for the renovation undertaken by the Duke and Duchess of Lauderdale, which have been attributed to John Slezer and Jan Wyck, demonstrate the continued importance of the garden design, with many features that exist today such as the Orangery, the Cherry Garden, the Wilderness and eight grass squares (plats) on the south side of the house.[201] Both the private apartments for the Duke and Duchess and the State Apartments added to the south front of the house were designed to overlook the formal gardens, an innovation that was highly commended by contemporaries.[202] John Evelyn remarked favourably on the garden design observed during his August 1678 visit, noting "...the Parterres, Flower Gardens, Orangeries, Growves, Avenues, Courts, Statues, Perspectives, Fountaines, Aviaries…".[203] The Duchess also commissioned a set of iron gates for the north entrance to the property, which remain in place today.[204]

The 3rd and 4th Earls of Dysart who subsequently inherited the estate maintained the formal garden features into the 18th century, while also planting avenues of trees in the wider vicinity.[205] After inheriting the estate in 1799, the 6th Earl opened the north front of the property to the river and installed the Coade stone statue of the River God at the front of the house.[206] He also created the ha-ha which runs along the north entrance of the property.[206] Louisa Tollemache, 7th Countess of Dysart, inherited the estate upon her brother's death and was acquainted with the artist John Constable, who completed a sketch of Ham House from the south gardens during a visit in 1835.[207]

By 1972, the gardens had become greatly overgrown – large bay trees at the front blocked the view of the busts in their niches, the south lawn had reverted to a single large expanse of grass and the Wilderness was overgrown with rhododendrons and sycamore trees.[208] Work to restore the 17th century design to the eastern and southern parts of the garden began in 1975.[209][162] In 1974, an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum entitled "The Destruction of the Country House" had included a model of Ham House with its gardens shown according to the 1672 plans created by Ms. Lucy (Henderson) Askew.[210] This model illustrated the details of the 17th-century design in terms of both layout and plant selection and was used to garner support for the restoration project.[210] By 1977, the grass plats and the structure of the Wilderness to the south of the house were re-established.[211] The 1675 painting by Hendrick Danckerts showing the Duke and Duchess in the south gardens was used to guide the restoration of the furniture and statues now in place.[212]

In approaching the restoration of the "cherry garden" on the east side of the house, there was less documentary evidence available to guide the design.[212] A set of diagonally-set parterres outlined by box hedges and cones were planted with lavender, with the whole garden being enclosed by tunnel arbours and double yew hedges.[213] Later archaeological studies completed in the 1980s indicated no evidence of formal gardens in this area prior to the 20th century;[212] despite this finding, the National Trust's Gardens Panel decided not to remove the garden, but rather allow it to remain so long as visitors to the property were clearly informed of its origins.[214] The focus of garden restoration since 2000 has been the walled kitchen garden to the west of the house, to restore its use as a supply of fresh fruit, vegetables and flowers.[212] The produce is used in the Orangery cafe, while the flowers are used to decorate the house. The garden itself is also used as an exhibition space, with information about tulip varieties and the range of edible flowers.[215]

Later owners

[edit]Lionel Tollemache, 3rd Earl of Dysart (1698–1727)

[edit]Elizabeth and Lionel Tollemache's eldest son and heir, Lionel, became 3rd Earl of Dysart on his mother's death in 1698, inheriting Ham House, the adjoining estates and the manors of Ham and Petersham.[216] Already the owner of his father's estates in Suffolk and Northamptonshire, he had also acquired 20,000 acres (8,100 ha; 31 sq mi) in Cheshire through his marriage in 1680 to Grace, daughter of Sir Thomas Wilbraham, 3rd Baronet.[216] He only spent short periods at Ham,[216] and apparently did little for the upkeep of the house though he kept the garden well.[217] He did use his wealth to pay off the interest on the outstanding mortgages but was not considered generous, even with his immediate family.[218] His only son, Lionel, predeceased him in 1712 and on his death he was succeeded as Earl of Dysart by his grandson, also named Lionel.[219]

Lionel, 4th Earl (1727–70)

[edit]

Lionel Tollemache was only 18 years old when he became the 4th Earl of Dysart and head of the family in 1727. Shortly after returning from the Grand Tour in 1729 he married Grace Carteret, the 16-year-old daughter of John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville,[220] and began repairing existing furniture as well as commissioning new pieces for his properties at Ham and at Helmingham Hall] in Suffolk.[220] Ham House had been largely neglected since the death of Elizabeth; in 1730 he ordered a structural survey of the building from John James which revealed serious problems, especially on the north front.[220] Repairs began in the 1740s. At the front of the house the "Advance", a projecting frontispiece which extended two storeys to form a porch over the main entrance, had become detached from the wall and was in danger of pulling down the roof. It was removed completely and the stone reused for repairs to the first and second floors. The canted bays on the projections at each end of the house were rebuilt as deeper three-window bays, with corresponding alterations made to the bays on the south front. Major repairs were also made to the roof, where old unfashionable red tiles on the outer pitches were replaced with slate and reused for repairs to the inner pitches where they would not be visible.[221]

Much new furniture was commissioned, but the 4th Earl seems to have also been committed to preserving existing artefacts, making repairs to fixtures from the Lauderdale period where necessary.[220] He made three large changes to the interior of the house: the Queen's Bedchamber on the first floor became the principal drawing room with furniture and tapestries supplied by the London upholsterer and textile producer William Bradshaw; the Volury[g] on the ground floor became another drawing room with the addition of tapestries and its distinctive X-framed seat furniture; and in the Dining Room the marble floor was replaced with marquetry, with matching gilded leather panels on the walls.[148] By means of his extensive investment, the house would have become sumptuously furnished by the mid-18th century.[115]

Of the sixteen children of the 4th Earl and Countess, only seven lived to maturity.[223] Three of their five sons died in the pursuit of their naval careers.[224] The Countess died in 1755 aged 42, and the Earl in 1770 aged 61.[225] He was survived by his sons Lionel, Lord Huntingtower, and Wilbraham, as well as three daughters: Jane, Louisa and Frances.[226]

Lionel, 5th Earl (1770–99)

[edit]Lionel Tollemache, 5th Earl of Dysart succeeded to the title in 1770 on his father's death.[227] Despite spending on the house, the 4th Earl had kept his son short of money during his lifetime, causing friction in the relationship; he married without his father's consent.[227] His wife, Charlotte, was the youngest illegitimate daughter of Sir Edward Walpole, second son of Robert Walpole, and niece of Horace Walpole who lived near to Ham across the Thames at Strawberry Hill.[227] The 5th Earl seems to have been a reclusive and introverted individual who shunned publicity,[228] preferring to remain on his estates and refusing to allow changes or renovations to Ham House.[229] His aversion to visitors was so marked as to lead him to refuse a request to visit from George III; "whenever my house becomes a public spectacle, His Majesty shall certainly have the first view".[66] In contrast to his conserving instincts at Ham, he demolished two properties in Northamptonshire and Cheshire, although retaining the productive, and lucrative, estates.[206] He continued the family tradition of acquiring fine furniture, most notably a marquetry commode which can be seen in the Queen's Bedchamber, and the sunburst chairs in the White Closet.[230]

Charlotte died, childless, in 1789 and although Lionel remarried he remained without an heir.[231] The families of his surviving sisters, Louisa and Jane, reverted to the family name of Tollemache in anticipation of eventual succession.[206] On his death in 1799 his brother, Wilbraham became the 6th Earl of Dysart.[232]

Wilbraham, 6th Earl (1799–1821)

[edit]

Wilbraham was aged 60 when he inherited the title in 1799. One of his first acts was to buy the rights of the Manor of Kingston/Canbury from George Hardinge, extending the Dysarts' property south into Kingston.[232] He had the wall which isolated the property and separated Ham House from the river demolished and replaced by a ha-ha,[232] leaving the gates free-standing. Coade stone pineapples were added to decorate the balustrades[233] to the north of the property and John Bacon's statue of the river god which is placed in front of the north entrance, pictured here, also in Coade stone,[3] dates from this period.[233] Several busts of Roman emperors which had adorned the now-demolished walls since the 17th century[234] were relocated to niches in the front of the house.[235] Further restoration of the old furniture took place as well as the addition of Jacobean reproductions.[235] The 6th Earl became a patron of John Constable at this time.[236][235] Wilbraham's wife died in 1804 and, devastated, he moved away, close to the estate in Cheshire.[235] Wilbraham died without heir in 1821, aged 82.[237]

Louisa, 7th Countess (1821–40)

[edit]

Of the 4th Earl's children, only the eldest daughter, Lady Louisa, by then widow of John Manners MP, was still surviving when her brother Wilbraham, the 6th Earl, died.[238] Already heiress to Manners' 30,000 acres (12,000 ha; 47 sq mi) at Buckminster Park, Louisa inherited the title and estates at Ham in 1821 at the age of 76.[238] The remaining Tollemache estates were bequeathed to the heirs of Lady Jane.[19] Louisa continued the patronage of John Constable who was a frequent and welcome visitor to Ham.[239] Increasingly infirm and blind in old age, Louisa lived to the age of 95, dying in 1840.[240]

Lionel, 8th Earl (1840–1878)

[edit]Louisa's eldest son, William, had predeceased her in 1833. Her grandson, Lionel William John Tollemache, inherited the title and became the 8th Earl of Dysart in 1840.[99] Lionel preferred to live in London and invited his brothers, Frederick and Algernon Gray Tollemache, to manage the estates and Ham and Buckminster.[241] Lionel became increasingly reclusive and eccentric. Lionel's only son, William, a controversial figure who amassed great debts guaranteed by the expectation of inheriting the family fortune[241] also predeceased his father, who subsequently bequeathed the estates to his grandson William John Manners Tollemache, with the 8th Earl's brothers Frederick and Algernon along with Charles Hanbury-Tracy acting as trustees until 1899.[242] Following the 8th Earl's death, his son's creditors brought an action in the High Court against the Tollemache family who ultimately had to pay a sum of £70,000 to avoid forfeiting much of the Ham estate.[99]

William, 9th Earl (1878–1935)

[edit]The 9th Earl inherited in 1878. In his autobiography, Augustus Hare recounts a visit to Ham House the following year, contrasting the dilapidation and disrepair of the house and estate with the treasures the house still contained.[243] Shortly afterwards, the 9th Earl, with agreement from the trustees, undertook extensive renovation of the house and its contents[244] and by 1885 it was again in a suitable state to host social activities, notably a garden party to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in 1887. In 1890 Ada Sudeley, a niece of the 8th Earl, published her 570-page book Ham House, Belonging to the Earl of Dysart.[245]

On 23 September 1899, full control of the Tollemache estates at Ham and Buckminster was transferred from trustees to the 9th Earl, then aged about 40, in accordance with his grandfather's will.[246] By the early 1900s the Dysarts had installed electricity and central heating at the house along with other modern gadgets including, in the Duchess's basement bathroom, a bath with jets and even a wave machine.[244] The 9th Earl travelled widely, rode despite blindness, invested successfully in the stock market, and while eccentric and difficult, nonetheless was hospitable and supportive of the local community.[247] His cantankerous nature proved too much for his wife who left him in the early 1900s but he lived on with other family members at Ham for many years.[246] In the 1920s and 1930s he employed a staff of up to 20 including a chauffeur for his four cars including a Lanchester and Rolls-Royce. When he died in 1935 he left investments worth £4,800,000 but had no direct heir.[248] He was the last Earl of Dysart to live at the house.[249]

Sir Lyonel Tollemache, Bt. (1935–52)

[edit]On the 9th Earl's death in 1935, his inheritance passed to the families of his sisters. His niece, Wynefrede, daughter of his sister Agnes, inherited the earldom.[250] Wynefrede's cousin, Lyonel, at the age of 81, inherited the baronetcy and the estates at Ham and Buckminster.[250] He and his middle-aged son, Cecil Lyonel Newcomen Tollemache, lived at the house, but the lack of available staff during the Second World War added to the difficulty of maintaining it. The nearby Hawker Siddeley aircraft factory was a target for bombing raids, and the house and grounds suffered some minor damage. Much of the house's contents were removed to the countryside for safety.[250] Most of the family papers were deposited in Chancery Lane but, while they survived the Blitz, they suffered significant water damage from fire hoses.[250] Thought for some time to have been lost, an additional set of papers was subsequently recovered from the Ham House stables in 1953, though many were in poor condition from inadequate storage conditions.[19]

National Trust (1948–present)

[edit]In 1943, Sir Lyonel invited the National Trust's first Historic Buildings Secretary, James Lees-Milne, to visit the house.[249] Lees-Milne saw the neglected state of the house and grounds but, even though devoid of its contents, the historical importance of the underlying estate was immediately apparent. He recorded his impressions in his diary for 1947, extracts from which were later reproduced in the volume Some Country Houses and their Owners: "The grounds are indescribably overgrown and unkempt. All the rooms are dirty and dusty. The garden and front doors look as they had not been used for decades."[251] Despite the neglect, a report commissioned by Lees-Milne in 1946 concluded that it was "by far the finest, most valuable and most representative building of the period to which it belongs in the United Kingdom".[249] Following lengthy negotiations, Sir Lyonel and his son donated the house and its grounds to the Trust in 1948.[252] The stables and other outlying buildings were sold privately and much of the remaining estate was auctioned in 1949.[253]

The National Trust at first transferred ownership of Ham House to the state on a long lease to the Ministry of Works.[254] The contents of the house were purchased by the government who entrusted them to the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A)[255] after considerable urging by the director of the museum, Sir Leigh Ashton.[h][257] His efforts were essential because the National Land Fund, which had been established in 1946 through the sale of surplus war materials, allowed for the purchase of property but not art or other interior furnishings.[258] The legislation was amended in 1953, following the agreement that properties such as Ham House ought to retain their historic collections.[259]

By 1950, the house was open to the public and a series of research and restoration works since undertaken, restoring and reproducing much of the house's former grandeur.[254] The arrival of Peter Thornton as the Keeper of the Furniture Department at the V&A led to a new approach in the management of the collection; efforts focused on arranging pieces within the house according to the documented history of the property, rather than treating individual items as simply part of the museum inventory.[260] Research on historic interiors emerged as a discipline from the late 1960s, with an important source made available through the publication of the Ham House bills and inventories in 1980.[261]

The government relinquished its lease in 1990, and the compensation was used to form a fund to support maintenance.[262] The collections were fully transferred from the V&A to the National Trust in 2002.[263] Since that time, the National Trust has invested in recreating the period interiors of the house by rehanging the collection and placing furniture according to inventory records as well as commissioning replica textiles based on archival descriptions.[264] To celebrate the 400th anniversary of the property, a symposium was held to stimulate interest in new research; this led to the publication of a major historical survey overseen by Christopher Rowell in 2013.[265] The Trust continues to acquire items at auction with a historical connection to the house, such as paintings which were formerly in the collection.[266][267] Restoration is an additional area of major investment, such as that completed for the Queen's Antechamber wallhangings in 2010.[268] In its 2018/2019 Annual Report, the Trust reported that Ham received 127,195 visitors.[269]

In film and television

[edit]Ham House is a popular film location.[i] It has also appeared in television and radio programmes.[271][272] Films that have used the house and its grounds include: Left Right and Centre (1959),[273] Spice World (1997), The Young Victoria (2009), Never Let Me Go (2010), Anna Karenina (2012),[274] John Carter (2012),[275] A Little Chaos (2014),[276] Victoria and Abdul (2017),[277] The Last Vermeer (2019),[270] and Rebecca (2020).[278] Television programmes filmed at Ham include: Steptoe and Son (1964),[279] Sense and Sensibility (2008),[280] Taboo (2017),[281] Bodyguard (2018),[282] Belgravia (2020),[283] The Great (2020),[284] Antiques Roadshow (2021),[285] and Mary & George (2024).[286]

Access

[edit]The house can be reached by public transport and is located in Transport for London travel zone 4; from Richmond station (London) the 65 bus service serves Petersham Road and the 371 bus service serves Sandy Lane. These routes terminate near Kingston station. There is a free council car park north-west of the house, next to the Thames. Hammerton's Ferry, to the north-east, links to a playground between Orleans House Gallery and Marble Hill House below Twickenham's central embankment. The house is accessible to pedestrians and cyclists via the Thames Path national trail.[287]

Notes

[edit]- ^ An H-plan building is one built to a plan resembling the shape of an H. It is a variant of the E-plan, comprising two Es placed back-to-back.[8] Sir John Summerson suggests Wimbledon Manor House as the first example of the type.[9]

- ^ Doreen Cripps notes that "some authorities...maintain that the title was not bestowed for another three years when Murray persuaded Charles to antedate it." She further observes that Katherine did not use the title, but remained "Mrs. Murray".[21]

- ^ Marcus Binney records that the Duke undertook simultaneous remodelling of his Scottish properties, Thirlestane Castle, Lennoxlove House and Brunstane.[46]

- ^ In 2020, the National Trust published a report on a survey completed to identify links between colonialism and the properties in its portfolio. The entry on Ham House noted that the Duke of Lauderdale was connected to organisations involved in colonialism and slavery.[130]

- ^ Simon Jenkins suggests that the intended visit by Queen Catherine may not in fact have taken place,[65] although other sources indicate a visit in 1674.[74]

- ^ Jeremy Musson, in his study How the Read a Country House, references the closets at Ham as among the "finest" late-17th century examples, and notes the derivation of the modern term cabinet government from Charles II's use of such closets, or cabinets, to discuss confidential matters.[165]

- ^ The room which had been the Duchess's Bedchamber, and later the Duke's, was fitted with a set of birdcages outside the south-facing windows. The name "Volury" is thought to derive from volière, the French word for birdcage.[222]

- ^ James Lees-Milne recorded the tortuous negotiations with HM Treasury in his diary: "After a great deal of manoeuvre I managed to insert a proviso that the N.T. should be consulted [over the] contents. The Government proposal is that they should keep the contents, and hold them through the V & A."[256]

- ^ The National Trust generates substantial income from the hiring of its properties as filming locations. Between 2002 and 2018, income of over £12M was raised in this way.[270]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Beard 1985, p. 96.

- ^ "The History of Ham House". Ham House and Garden. National Trust. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cherry & Pevsner 2002, p. 474.

- ^ a b Norwich 1985, p. 360.

- ^ a b Malden 1911, pp. 501–516.

- ^ a b c d Pritchard 2007, p. 1.

- ^ a b Beddard, Robert (January 1995). "Ham House". History Today. 45 (1). Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 372.

- ^ Summerson 1955, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 3.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Jackson-Stops 1979, p. 21.

- ^ Pritchard 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 15.

- ^ Airs 1998, p. 152.

- ^ NT 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Millar 1958, p. 77&96.

- ^ a b c "Estates of the Tollemache Family of Ham House in Kingston upon Thames, Ham, Petersham and Elsewhere: Records, 14th cent–1945". Surrey History Centre. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ Pritchard 2007, p. 4.

- ^ Cripps 1975, p. 10.

- ^ Harwood & Murray 1906, pp. 402–403.

- ^ Parliamentary Committee Document CMS1140464. Ham House NT.

- ^ "Mr. Murray's Sequestration Stayed". Journal of the House of Lords: 1644. Institute of Historical Research. 14 June 1645.

- ^ "Order to Free Mr. Murray's Estate from Sequestration". Journal of the House of Lords (1645–1647). Institute of Historical Research. 18 April 1646.

- ^ a b NT 2009, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Pritchard 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Pritchard 2007, p. 8.

- ^ "Elizabeth Murray". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19601. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ NT 2009, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Rowell 2013, p. 95.

- ^ Jackson-Stops 1979, p. 32.

- ^ Akkerman 2018, pp. 121–122.

- ^ NT 2009, p. 77.

- ^ Cripps 1975, p. 67.

- ^ a b Pritchard 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Surrey History Centre, ref 59/2/4/1, cited in Pritchard 2007, p.12.

- ^ Cripps 1975, p. 14.

- ^ Thrush, Andrew; Ferris, John P. "MURRAY, William (c.1600–1655), of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Westminster and Ham, Surr". The History of Parliament. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Akkerman 2018, p. 124.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 119.

- ^ Cripps 1975, p. 82.

- ^ Cripps 1975, p. 79.

- ^ Cripps 1975, p. 113.

- ^ Fraser 1979, p. 397.

- ^ Binney 2007, p. 785.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e Cherry & Pevsner 2002, p. 475.

- ^ a b c Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Bracken, Gáldy & Turpin 2020, p. 36.

- ^ a b Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 118.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 445.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 84.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 37.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 141.

- ^ Curl 2016, p. 244.

- ^ NT 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Wilson 1977, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Murdoch, Alexander (2004). "Campbell, John, Second Duke of Argyll and Duke of Greenwich (1680–1743)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4513. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c Pritchard 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Pritchard 2007, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Pritchard 2007, p. 23.

- ^ Pritchard 2007, p. 24.

- ^ Wilson 1977, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Jenkins 2003, pp. 494–495.

- ^ a b Norwich 1985, pp. 359–360.

- ^ Cherry & Pevsner 2002, pp. 474–477.

- ^ a b "Plan of Ham House and Gardens by Robert Smythson, c. 1609". British Architectural Library, ID: no. 12941. RIBA.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d Greeves 2008, pp. 153–155.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Rowell 2013, pp. 172–173.

- ^ a b Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 4.

- ^ a b Rowell 2013, p. 122.

- ^ Louw 1983, p. 49.

- ^ Rowell 2013, pp. 109–110.

- ^ NT 2009, p. 7.

- ^ NT 2009, p. 9.

- ^ "What are Listed Buildings?". Historic England. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Ham House (Grade I) (1080832)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "About Accreditation". Arts Council England. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Ham House Park and Garden (Grade II*) (1000282)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Forecourt of Ham House (Grade II) (1192685)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Entrance Gate and Railings of Forecourt to Ham House (Grade II) (1358078)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Garden Walls and Gatepiers to South of House (Grade II) (1080833)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Tea Room (Grade II) (1192746)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Ice House (Grade II) (1358079)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Service Yard Entrance to West of House (Grade II) (1358096)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Ham House Gatehouse and Attached and Associated Gatepiers (Grade II) (1389381)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. IX.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 38.

- ^ "Charlotte Walpole, Countess of Dysart (1738–1789) – Item NT1139646". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Anna Maria Lewis, Countess of Dysart (1745–1804) – Item NT1140004". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Lady Louisa Tollemache, Countess of Dysart (1745–1840) – Item NT1140003". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Lionel Tollemache, 4th Earl of Dysart (1708–1770) – Item NT1139649". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Lady Grace Carteret, Countess of Dysart (1713–1755) – Item NT1139647". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 96.

- ^ NT 2009, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c Rowell 2013, p. 370.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, pp. 97–99.

- ^ a b Rowell 2013, p. 73.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cherry & Pevsner 2002, p. 476.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 75.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 101.

- ^ "Venus with Mercury and Cupid (The School of Love) – Item NT1139671". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "The Venus Del Pardo (Venus and a Satyr) – Item NT1139666". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 22.

- ^ Jackson-Stops 1979, p. 23.

- ^ "John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale (1616–1682) and Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Dysart and Duchess of Lauderdale (1626–1698) – Item NT1139789". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ a b Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 24.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 56.

- ^ a b Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 34.

- ^ Thornton 1980, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 183.

- ^ a b NT 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Standen 1971, p. 5.

- ^ Ward 1953, p. 114.

- ^ Thornton & Tomlin 1980, p. 26.

- ^ "Sir John Maitland, 1st Baron Maitland of Thirlestane (1543–1595), aged 44 – Item NT1139943". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Revealing Ham House's Hidden Portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Rowell 2013, p. 145.

- ^ "King Charles I (1600–1649) – Item NT1139944". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Colonel The Hon. John Russell (1620–1681) – Item NT1139947". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ Waterhouse 1994, p. 65.

- ^ "Elizabeth Murray with a Black Servant – Item NT1139940". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale (1616–1682) in Garter robes – Item NT1139952". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ "Thomas Clifford, 1st Baron Clifford of Chudleigh KG (1630–1673) in Garter robes – Item NT1139953". National Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ a b Bracken, Gáldy & Turpin 2020, p. 30.