Bininj

The Bininj are an Aboriginal Australian people of Western Arnhem land in the Northern Territory. The sub-groups of Bininj are sometimes referred to by the various language dialects spoken in the region, that is, the group of dialects known as Bininj Kunwok; so the people may be named the Kunwinjku, Kuninjku, Kundjeyhmi (Gundjeihmi), Manyallaluk Mayali, Kundedjnjenghmi and Kune groups.

Three languages are spoken among the Mirrar or Mirarr clan group, who are prominent in matters relating to looking after the traditional lands. The majority speak Kundjeyhmi, while others speak Gaagudju and others another language.

History

[edit]Aboriginal peoples have occupied the Kadadu area for about 65,000 years.[1]

The Macassans from Sulawesi had been in contact for trade purposes for centuries before the arrival of white civilization. They sailed down to exchange a variety of their goods for trepang, and the impact of their presence is evidenced by the retention in some Bininj Kunwok dialects of a few dozen foreign loan words from the language of these traders. They were depicted by local artists in the Indigenous Australian rock art still conserved in a variety of sites around the Mann River. The first recorded European penetration of these territories was undertaken by Francis Cadell who reached the Kuninjku territory on the Liverpool river. The Liverpool area was surveyed by David Lindsay on behalf of the government in 1884.[2]

Rock art known as the Dynamic Figures, referring to a particular series of works in Mirrar country, was described by art historian George Chaloupka and is often referred to when writing about rock art in Arnhem Land.[3][4]

Name

[edit]The literal meaning of Bininj is human being, Aboriginal vs non-Aboriginal person, and also "man" in opposition to "woman".[5] "Bininj" is a word in the Kunwok language, often referred to by its dominant dialect Kunwinjku.[6]

Country

[edit]

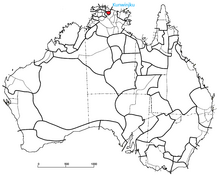

Their territory extends from Kakadu National Park to the west, the Arafura Sea to the north, the Blyth River to the east, and the Katherine region to the south. The traditional lands of the Bininj were located west of the Goomadeer River, north around the King and Cooper Rivers, south towards the East Alligator River, and extending to Gunbalanya (Oenpelli).[7]

A large part of Kakadu National Park, including areas where Bininj Kunwok is spoken, was returned to Aboriginal ownership in 2022.[8]

Language

[edit]Bininj Kunwok refers to six closely related languages and dialects, spoken from Kakadu National Park, southwards to Pine Creek and Manyallaluk, across the Arnhem Plateau, and eastwards to the Liverpool River and its tributary the Mann River, and Cadell river districts.[9] The classification, encompassing the mutually intelligible languages, respectively Kunwinjku, Kuninjku, Kundjeyhmi, Manyallaluk Mayali, Kundedjnjenghmi, and two varieties of Kune, was made by Nicholas Evans.[9][10] Their word for Europeans is balanda, a loan-word from Macassan traders, in whose language it meant "Hollanders".[11]

In addressing djang spirits (see below) a special language called kundangwok,[12] which is specific to each particular clan, must be employed.[13]

Social groupings according to dialect

[edit]- The Kunwinjku's original heartland is said to have been in the hilly terrain south of Goulburn Island and their frontier with the Maung running just south of Tor Rock. Their northern extension approached Sandy Creek, while they were also present south-east at the head of Cooper's Creek and part of the King River.[14] In Norman Tindale's scheme, the Kunwinjku were allotted a tribal territory of around 2,800 square miles (7,300 km2) in the area south of Jungle Creek and on the headwaters of the East Alligator River.[15] The Gumader swamps near Junction Bay and the creeks east of Oenpelli/Awunbelenja also formed part of their land.[16]

- The Kundjeyhmi, specifically the Mirrar or Mirarr clan, live around Jabiru between the East and South Alligator rivers. They formed the Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation, to represent the interests of the traditional owners of the land, the Mirrar, as well as other Bininj peoples of Kakadu.[17] One of the biggest issues in recent times is uranium mining, and the transition of the area once the last mining lease ends and all operations cease in 2021.[18]

- The Mayali lived further south across the South Alligator River, with the Katherine River on their eastern flank.

- The Kundedjnjenghmi moved around the Upper Liverpool and Mann rivers to the east of the Kunwinjku and Kundjeyhmi.

- The Kuninjku lived north of the Kundedjnjenghmi and south-west of Maningrida,[19] which serves as their centre for services. Many live in some 15 outstations, such as Kumurrulu at Manggabor Creek above the Liverpool River floodplain.[20]

- The Kune lived east of the Kuninjku, living around the Cadell River.[7]

NOTE: Three languages are spoken among the Mirrar or Mirarr clan group, apart from English. The majority speak Kundjeyhmi, while others speak Gaagudju and others another language.[21][22]

Social system

[edit]The Kunwinjku social system was analysed in detail in a 1970 monograph by Ronald Berndt and Catherine Berndt.[23]

Mythology

[edit]

Like the Aboriginal peoples generally of the Western Arnhem, land, the Bininj believed in the primordial creative function of a Rainbow serpent, which is generally[a] called Ngalyod[b] which has lineaments more suggestive of the feminine than masculine. It came to Australia from the sea northeast of the Cobourg Peninsula[25] When Baldwin Spencer visited the area and was a guest at Cahill's homestead at Oenpelli, he picked up one version which spoke of the same figure as being called Numereji[c][d] Legend has it coming from the north, full of spirit-children, and settling at a point called Coopers Creek on the East Alligator River, she transformed her children into men, creating waterholes to cater to their thirst, supplying men with spears and woomera, and women with dilly bags and digging sticks, while endowing both with intelligence and their senses. She swallows those who infringe her laws, and drowns children who cry, since she is disturbed by noise.[26]

In Dreaming narratives, when Ngalyod surges from the earth to devour some ancestral species, it does so because a taboo has been violated, and the act sanctifies the site.[13]

- For the Kuninjku important dreaming sites (djang) are the Leech Dreaming at Yibalaydjyigod in the swamps of the Manggabor Creek, the Maggot Dreaming at Yirolk, where a rock, girdled by water lilies, rises out of a waterhole and the Barramundi Dreaming around Marrkolidjban. The former two are likened to the Rainbow serpent, connoting, by battening on flesh, themes of decay and rebirth[27] The souls (kunmalng) of the Kuninjku are themselves derived from the water spirits at such sites.[28] The rejuvenating monsoonal downpours are caused by the flight of Ngalyod from its underground sanctuary into the sky, marked by the rainbow. Increase ceremonies like the Kunabibi and yabbadurruwa rites are performed in order to incite the djang to stir the onset of the fertilizing rains.[29]

Notable people

[edit]- John Mawurndjul, Kuninjku artist of international fame[30]

- Bardayal 'Lofty' Nadjamerrek

- Bobby Nganjmirra, Kunwinjku artist

See also

[edit]- Lorrkkon, a hollow log coffin or memorial pole

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ According to Taçon, the Rainbow Snake/Woman is known as Yingarna by the Kunwinnnjku, a woman called Imberombera or Warraamurrungundji by the Gaagudju and Iwaidja peoples, while among the Gundjeibmi the ancestral woman turned rainbow serpent is Almudji (Taçon 2011, p. 84).

- ^ Ngalyod is often said[24] to be the son of Yingarna.

- ^ Mountford 1978, p. 78 n.31 identifies Numereji as identical to Ngalyod

- ^ Numereji emerged at Kumbulmorma, and devoured a large tribe at Yiringira, after hearing a baby crying. Calling out Waji bialilla, yana. waji bialilla("there is a child crying, where is the child crying?") He slithered up, and sucked in the child, and then the natives, save for an old woman, Kominiyamana, who hid up a tree and managed to avoid being swallowed until smacking at mosquitoes, she gave her position away. He moved off sated, crossed the East Alligator River, at Maipolk, and frightened the local birdlife, which flew off screaming, thereby alerting the next tribe to his presence. They examined the sleeping hulk of the creature, who did not reply to their queries, but they knew it must be Numereji. One elder finally said: Urawulla jereini jau (It's Urawulla men whom you have eaten', at which the rainbow serpent vomited the bones of his victims, which can be seen to this day, in the form of stones. At this Numereji went underground at Mungeruauera (Spencer 1914, pp. 290–291).

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Wright, Tony (19 July 2017). "Aboriginal archaeological discovery in Kakadu rewrites the history of Australia". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Garde 2013, p. 18.

- ^ Johnston, Goldhahn & May 2017.

- ^ Taçon et al. 2020, pp. 1–18.

- ^ BKOD, bininj.

- ^ BKOD, kunwok.

- ^ a b Garde 2013, p. 15.

- ^ Gibson, Jano (24 March 2022). "Nearly half of Kakadu National Park to be handed back to Aboriginal traditional owners". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ a b Garde 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Evans 2003.

- ^ Scambary 2013, p. 110.

- ^ BKOD, kundangwok.

- ^ a b Taylor 2012, p. 28.

- ^ Elkin, Berndt & Berndt 1951, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Tindale 1974, p. 226.

- ^ Elkin, Berndt & Berndt 1951, p. 254.

- ^ GAC: Mirarr 2020.

- ^ GAC: Uranium mining.

- ^ Taylor 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Taylor 2012, pp. 23, 25.

- ^ "Mirarr - Indigenous Peoples". Intercontinental Cry. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ "Mirarr Aboriginal Corporation". The Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation. Retrieved 24 October 2021.

- ^ Berndt & Berndt 1970.

- ^ Taçon 2011, p. 84.

- ^ Mountford 1978, p. 78.

- ^ Mountford 1978, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Taylor 2012, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Taylor 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Taylor 2012, p. 29.

- ^ Taylor 2015, p. 108.

Sources

[edit]- Berndt, Ronald Murray; Berndt, Catherine Helen (1970). Man, Land and Myth in Northern Australia: The Gunwinggu people. Ure Smith.

- Elkin, A. P.; Berndt, R. M.; Berndt, C. H. (June 1951). "Social Organization of Arnhem Land". Oceania. 21 (4): 253–301. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1951.tb00176.x. JSTOR 40328302.

- Evans, Nicholas (2003). Bininj Gun-wok: a pan-dialectal grammar of Mayali, Kunwinjku and Kune. ANU Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies. ISBN 978-0-858-83530-6.

- Garde, Murray. "Bininj Kunwok Online Dictionary". njamed.com. Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- Garde, Murray (2008). "Personal names, proper names and circumspection in Bininj Kunwok conversation". In Mushin, Ilana; Baker, Brett (eds.). Discourse and Grammar in Australian Languages. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 203–233. ISBN 978-9-027-29034-2.

- Garde, Murray (2013). Culture, Interaction and Person Reference in an Australian Language: An ethnography of Bininj Gunwok communication. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-9-027-27124-2.

- Johnston, Iain G.; Goldhahn, Joakim; May, Sally K. (2017). "6. Dynamic Figures of Mirarr Country: Chaloupka's four-phase theory and the question of variability within a rock art style". In David, Bruno; Taçon, Paul S.C.; et al. (eds.). The Archaeology of Rock Art in Western Arnhem Land, Australia. Terra Australis, 47. ANU Press. ISBN 978-176046162-1.

- "Mirarr". The Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation. 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- Mountford, Charles (1978). "The Rainbow- Serpent Myths of Australia". In Buchler, Ira R.; Maddock, Kenneth (eds.). The Rainbow Serpent: A Chromatic Piece. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 23–97. ISBN 978-3-110-80716-5.

- Scambary, Benedict (2013). My Country, Mine Country: Indigenous People, Mining and Development Contestation in Remote Australia. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-1-922-14473-7.

- Spencer, Baldwin (1914). Native Tribes of the Northern Territory of Australia. Macmillan and Co.

- Taçon, Paul S. C.; May, Sally K.; et al. (30 September 2020). "Maliwawa figures—a previously undescribed Arnhem L and rock art style". Australian Archaeology. 86 (3): 208–225. doi:10.1080/03122417.2020.1818361. ISSN 0312-2417.(About the Maliwawa Figures)

- Taçon, Paul S.C. (2011). "Identifying Ancient Sacred Landscapes in Australia: Frtom Physical to Social". In Preucel, Robert W.; Mrozowski, Stephen A. (eds.). Contemporary Archaeology in Theory: The New Pragmatism. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 77–91. ISBN 978-1-444-35851-3.

- Taylor, Luke (2012). "Connections of Spirit: Kuninjku Attachments to Country". In Weir, Jessica K. (ed.). Country, Native Title and Ecology. Australian National University. pp. 21–47. ISBN 978-1-921-86256-4.

- Taylor, Luke (2015). "Categories of 'Old' and 'New' in West Arnhem Land Bark Painting". In McGrath, Ann; Jebb, Mary Anne (eds.). Long History, Deep Time: Deepening Histories of Place. Australian National University. pp. 101–118. ISBN 978-1-925-02253-7.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Gunwinggu (NT)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "Uranium Mining". The Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- "Kured [home page]". Bininj Kunwok. Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre.