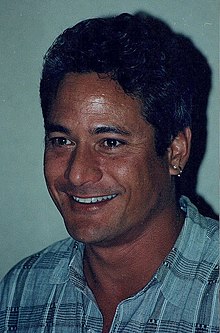

Greg Louganis

Gregory Efthimios Louganis (/luːˈɡeɪnɪs/;[1] born January 29, 1960) is an American Olympic diver who won gold medals at the 1984 and 1988 Summer Olympics on the springboard and platform. He is the only man and the second diver in Olympic history to sweep the diving events in consecutive Olympic Games. He has been called both "the greatest American diver"[2] and "probably the greatest diver in history".[3]

Early life and education

[edit]Louganis was born in El Cajon, California, and is of Samoan and Swedish descent. His teenage biological parents placed him for adoption when he was eight months old and he was raised in California by his adoptive parents, Frances and Peter Louganis. His adoptive father was of Greek descent.[4] Louganis reconnected with his biological father, Fouvale Lutu, in 1984. Through the help of DNA tests and his half-siblings, he found his biological mother in 2017.[5]

He started taking dance, acrobatics, and gymnastics classes at 18 months, after witnessing his sister's classes and attempting to join in. By the age of three, he was practicing daily and was competing and giving public performances.[6] For the next few years, he regularly competed and performed at various places including nursing homes and the local naval base. As a child, he was diagnosed with asthma and allergies, so to help with the conditions, he was encouraged to continue the dance and gymnastics classes. He also took up trampolining, and at the age of nine began diving lessons after the family got a swimming pool.[7] He attended Santa Ana High School in Santa Ana, Valhalla High School in El Cajon, and Mission Viejo High School in Mission Viejo.

In 1978, he subsequently attended the University of Miami, where he majored in drama and continued diving. In 1981, he transferred to the University of California, Irvine, where he graduated with a major in theater and a minor in dance in 1983.[8]

Diving career

[edit]As a Junior Olympic competitor, Louganis caught the eye of Sammy Lee, two-time Olympic champion, who began coaching him.[9] At 16, Louganis took part in the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, where he placed second in the tower event, behind Italian sport legend Klaus Dibiasi. Two years later, with Dibiasi retired, Louganis won his first world title in the same event with the help of coach Ron O'Brien.

Louganis was a favorite for two golds in the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, but an American boycott of the games prevented him from participating. He was one of 461 athletes to receive a Congressional Gold Medal years later.[10] Louganis won two titles at the world championships in 1982, where he became the first diver in a major international meeting to get a perfect score of 10 from all seven judges.[7] At the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, with record scores and leads over his opponents, Louganis won gold medals in both the springboard and tower diving events.

He won two more world championship titles in 1986.

At the 1988 Seoul Olympics, he struck his head on the springboard during the preliminary rounds, leading to a concussion.[6] He completed the preliminaries despite his injury. He then earned the highest single score of the qualifying round for his next dive and repeated the dive during the finals, earning the gold medal by a margin of 25 points.[7] In the 10 m finals, he won the gold medal, performing a 3.4 difficulty dive in his last attempt, earning 86.70 points for a total of 638.61, surpassing silver medalist Xiong Ni by only 1.14 points.[7] His comeback earned him the title of ABC's Wide World of Sports "Athlete of the Year" for 1988.[11]

HIV status and head injury

[edit]Six months before the 1988 Seoul Olympics, Louganis was diagnosed with HIV and started antiretrovirals.[12] After Louganis came out publicly as HIV-positive in 1995, people in and out of the international diving community began to question Louganis's decision not to disclose his HIV status at the time of his head injury during the 1988 Olympics, given that he had bled into a pool that others then dove into. Louganis has stated that, during the ordeal, he was "paralyzed with fear" that he would infect another competitor or the doctor who treated him. Ultimately, no one else was infected.[13] John Ward, chief of HIV-AIDS surveillance at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, noted that the incident posed no risk to others because any blood was highly diluted by the pool water and "chlorine kills HIV".[14] Since skin is an effective barrier to HIV, the only way the virus could enter would be through an open wound; "If the virus just touches the skin, it is unheard of for it to cause infection: the skin has no receptors to bind HIV," explained the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases' Anthony Fauci at the time.[14]

Endorsement deals

[edit]Louganis got few endorsement deals following his 1984 and 1988 Olympic victories, his one major deal being Speedo, a partnership which lasted until 2007. Some of his fellow athletes blamed homophobia for his lack of deals, since he had been rumored to be gay even before he came out.[15] Louganis has stated that he suspects that his sexuality played a part, although he feels that in part he was simply overshadowed in the public imagination by other American Olympians, most notably Mary Lou Retton.[16]

In 2016, Louganis was pictured on boxes of Wheaties cereal, where prominent American athletes are famously featured, as part of a special "Legends" series that also included 1980s Olympians Janet Evans and Edwin Moses.[16] This occurred approximately a year after a Change.org petition was launched that requested that he be featured, although General Mills denied any influence from the petition.[17]

Coaching

[edit]In November 2010, Louganis began coaching divers of a wide range of ages and abilities in the SoCal Divers Club in Fullerton, California.[18]

He was a mentor to the U.S. diving team at the London 2012 Olympics and the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympics.[6][19]

Media career

[edit]Acting

[edit]Louganis had been a theater major in college, and in the late 1980s and 1990s, he appeared in a number of movies, including Touch Me in 1997.[20]

In 1993, he played the role of Darius in an Off-Broadway production of the play Jeffrey.[21] In 1995, he starred for six weeks in the Off-Broadway production of Dan Butler's one man-show about gay life, The Only Thing Worse You Could Have Told Me, taking over from Butler himself. In the play he portrayed 14 different characters.[22]

In 2008, he appeared in the film Watercolors, in the role of Coach Brown, a swimming instructor in a high school.

In 2012, he appeared in the ninth episode of the second season of IFC's comedy series Portlandia, playing himself.

Television

[edit]In September 2000, Louganis appeared on Hollywood Squares as a member of famous Olympic gold medalists "Dream Team."

In 2013, Louganis was Dive Master in the celebrity diving show Splash on ABC, and a diving judge on Celebrity Splash! on Channel 7 in Australia.[23][24]

In 2020, he was a diving judge on the second season of the ABC show Holey Moley.[25]

Books and video diary

[edit]In 1996, Louganis recounted his story in a bestselling autobiography, Breaking the Surface, co-written with Eric Marcus. In the book, Louganis detailed a relationship of domestic abuse and rape as well as teenage depression, and how he began smoking and drinking at a young age.[7] The book spent five weeks at number one on The New York Times Best Seller list.

In 1998, Louganis released a video diary called Looking to the Light, which picked up where Breaking the Surface left off.

In 1999, Louganis co-wrote the book For the Life of Your Dog: A Complete Guide to Having a Dog From Adoption and Birth Through Sickness and Health with Betty Sicora Siino.[26][27][28]

Dog agility competitions

[edit]After retiring from diving, Louganis began to compete in dog agility competitions; he has said that being around the dogs gave him "a sense of security, company and unconditional love".[2] His dogs have included Dr. Schivago; Captain Woof Blitzer; Nipper and son, Dobby, both champion Jack Russell terriers; Gryff (Gryffindor), a border collie; and Hedwig, a Hungarian Pumi. Nipper was named for the RCA dog, while Gryff, Dobby and Hedwig were named for Harry Potter characters, as Louganis is a self-described "huge Harry Potter fan."[29][30][31][32][33]

Activism

[edit]

Louganis is a gay rights activist,[34][35][36] as well as an HIV awareness advocate. He has worked frequently with the Human Rights Campaign to defend the civil liberties of the LGBT community and people diagnosed with HIV/AIDS.[37]

In the October/November 2010 issue of ABILITY Magazine, Louganis stated that the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy was "absurd," "unconstitutional," and a "witch-hunt." He added that "gay men and women have been serving this country for years ... [it's] basically encouraging people who are serving our country to lie to each other."[38]

Louganis is on the board of directors to the USA-based chapter of the charitable foundation of Princess Charlene of Monaco.[39]

In 2023, it was reported that Louganis is auctioning three of his five Olympic medals in an effort to fund the Damien Center, Indiana's oldest and largest AIDS services center. "The medals, they're in the history books," he said. "Instead of holding on to them, I'm aiming to share my piece of Olympic history with collectors; together, we can help the Damien Center and its community to grow and thrive."[40]

Personal life

[edit]

From 1983 to 1989, Louganis was involved romantically with his manager, R. James "Jim" Babbitt. Louganis has described the relationship as abusive, saying that, at one point in 1983, Babbitt raped him at knife point.[13] Louganis also accused Babbitt of taking 80 percent of his earnings.[41]

Six months before the 1988 Olympics, Louganis was diagnosed with HIV; he had contracted the virus from Babbitt.[13] His doctor placed him on the antiretroviral drug AZT, which he took every four hours round the clock.[13]

In 1989, Louganis obtained a restraining order against Babbitt.[41] Babbitt died of AIDS in 1990.[13]

When Louganis turned 33, in 1993, he agreed to gather friends and family for a birthday party, but one that he envisioned as a final goodbye, as he was in failing health and thought he would soon die of AIDS.[3]

But, with treatment, he kept going and, in 1994, at the opening ceremony at that year's Gay Games, Louganis came out publicly as gay in a pre-taped announcement, at the encouragement of the event's organizers.[42] Even before then, however, he led a life that has been described as "openly gay."[13]

In 1995, around the time of the release of his memoir, Breaking the Surface, Louganis revealed his HIV status in an interview with Barbara Walters, speaking openly, for the first time, about being both gay and HIV-positive.[6]

In June 2013, Louganis announced, in People magazine, his engagement to his partner, paralegal Johnny Chaillot.[43] The two were married on October 12, 2013,[44] but on June 18, 2021, Louganis revealed on Instagram that he and Chaillot were ending their marriage.[45]

In popular culture

[edit]Actor Michael Fassbender took Louganis's gait and mannerisms as inspiration for his portrayal of an advanced humanoid robot in the 2012 film Prometheus,[46] stating that "Louganis was my first inspiration. I figured that I'd sort of base my physicality roughly around him, and then it kind of went from there."[47]

Louganis was the subject of the documentary Back on Board which aired on HBO on August 4, 2015.[48]

Awards and honors

[edit]

- In 1984, Louganis received the James E. Sullivan Award from the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) as the most outstanding amateur athlete in the United States.

- In 1988, he was awarded "Athlete of the Year" by ABC's Wide World of Sports.[11]

- In 1989, he was nominated for "Best Male Athlete" by the Kids' Choice Awards.

- In 1991, Greg was inducted into the University of Miami Sports Hall of Fame.

- In June 2013, Louganis was inducted into the California Sports Hall of Fame.[49] He was among the first class of inductees into the National Gay and Lesbian Sports Hall of Fame on August 2, 2013.[50]

- In April 2015, Louganis was presented the Bonham Centre Award from The Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, University of Toronto, for his contributions to the advancement and education of issues around sexual identification.[51]

- In July 2015, he was a torch bearer for the 2015 Special Olympics World Summer Games in Los Angeles.[52]

- In January 2017, he was a Grand Marshal of the Rose Parade in Pasadena, California.[53]

Bibliography

[edit]- 1996 – Breaking the Surface

- 1999 – For the Life of Your Dog[54]

Filmography

[edit]- Dirty Laundry (1987) as Larry

- Inside Out III (1992) as Max in the segment "The Wet Dream"

- D2: The Mighty Ducks (1994) as himself

- It's My Party (1996) as Dan Zuma

- Breaking the Surface: The Greg Louganis Story (1997)

- Touch Me (1997) as David

- Sports Theater with Shaquille O'Neal (episode: "Broken Record") (1997 TV movie) as Coach Hill

- Watercolors (2008) as Coach Brown

- 30 for 30: "Tim Richmond: To the Limit" (2010)

- Portlandia, season 2, episode 9 (2012) as himself

- Splash (2013) as himself

- Celebrity Splash! (2013) as himself

- Back on Board: Greg Louganis (2014)

- Sabre Dance (2015) as Salvador Dalí

- Entourage (2015) as a fictional version of himself

- 30 for 30: Thicker than Water (2015)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "HIV". Second Opinion. Season 15. Episode 7. 1 minutes in. WXXI Public Broadcasting Council. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Daniel, Heath (July 14, 2014). "Greg Louganis Tells How He Went From Heartthrob To Activist With Candid New Film". Queerty.

- ^ a b O'Neill, Tracy (August 4, 2015). "Greg Louganis: Far From Falling". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ Jordan, Pat. "Greg Louganis After The Gold". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Greg Louganis' Adoption Story & Heartwarming Reunion with His Birth Father". People.

- ^ a b c d Ain, Morty (June 23, 2016). "'I didn't think I'd see 30,' says Greg Louganis". ESPN The Magazine. No. Body Issue 2016. ESPN. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Simon Burnton (March 28, 2012). "50 stunning Olympic moments No20: Greg Louganis's perfect dive 1988". The Guardian.

- ^ SLATE, LIBBY (August 2, 1989). "Greg Louganis Plunges Into Light Opera : Olympic Diver Plays Prince in 'Cinderella'". Retrieved November 18, 2018 – via LA Times.

- ^ Beard, Alison (July 1, 2016). "Life's Work: An Interview with Greg Louganis". Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Caroccioli, Tom; Caroccioli, Jerry (2008). Boycott: Stolen Dreams of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games. Highland Park, IL: New Chapter Press. pp. 243–253. ISBN 978-0942257403.

- ^ a b "ABC Sports - Wide World of Sports".

- ^ Onion, Amanda (June 10, 2021). "How Greg Louganis' Olympic Diving Accident Forced a Conversation About AIDS". HISTORY. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Public Glory, Secret Agony". Newsweek. March 5, 1995.

- ^ a b "The Risk Pool: The Dangers Are Off The Field", authored by Sharon Begley, Newsweek, 5 March 1995

- ^ Crouse, Karen (August 14, 1994). "Many Endorsement Deals Aren't Coming Out -- Many Gay Athletes Have Learned They Must Stay In The Closet In Order To Land Lucrative Contracts". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Beard, Alison (April 5, 2016). "The Wheaties Box and the Why of Celebrity Endorsements". Harvard Business Review.

- ^ Better Late Than Never: Olympic Champion Greg Louganis Gets His Wheaties Box (NPR)

- ^ Crouse, Karen (February 20, 2011), "Louganis is Back on Board", The New York Times

- ^ Attitude (magazine) interview, August 2012

- ^ "Touch Me". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Greg Louganis. Steve Wulf. Sports Illustrated. September 27, 1993. Retrieved February 10, 2017

- ^ Winship, Frederick M. (August 22, 1995). "Greg Louganis, from platform to boards". UPI.

- ^ "I Went to the Set of Splash and Greg Louganis Taught Me How to Dive. Check Out the Video and Photos!". Glamour. April 2, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Exclusive: Greg Louganis Talks About Diving Into Celebrity Splash". TVGuide.com. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Greg Louganis, Joey Cifelli Guest Star on ABC Game Show". Swimming World News. May 29, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ For the Life of Your Dog. A Complete Guide to Having a Dog From Adoption and Birth Through Sickness and Health. Simon & Schuster, Inc. October 1999. ISBN 978-0-671-02451-2. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ "Greg Louganis - A chat with the author of 'For the Life of Your Dog' - A Complete Guide to Having a Dog in Your Life, From Adoption and Birth Through Sickness and Health". CNN. 2001. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ Louganis, Greg; Sikora, Betsy Siino (October 1999). For the Life of Your Dog: A Complete Guide to Having a Dog From Adoption and Birth Through Sickness and Health. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-02451-2. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ Greg Louganis back in the pool to help others Sandra Hewitt. ESPN. May 26, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ Greg Louganis Loves Dogs and Harry Potter: In the LINK of an Eye People Pets. Popsugar. February 2, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2017

- ^ London 2012 Olympics: diving champion Greg Louganis on the Games, Harry Potter and meeting Michelle Obama Greg Louganis. The Telegraph. August 7, 2012. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ Zeigler, Mark (June 13, 2009), "Life for Louganis more about dogs than diving", The San Diego Union Tribune, archived from the original on June 16, 2009, retrieved June 14, 2009

- ^ "Olympic Superstars: Where Are they Now? | Maxim". www.maxim.com. July 6, 2012. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ Greg Louganis Tells How He Went From Heartthrob To Activist With Candid New Film Heath Daniels. Queerty. July 14, 2014. Retrieved November 23, 2016

- ^ Greg Louganis: Champion, Survivor, Activist, Mentor Archived November 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine GregLouganis.com. August 23, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- ^ Greg Louganis: Champion, survivor, activist, mentor Jackie Bamberger. Yahoo Sports. August 5, 2016. Retrieved November 23, 2016

- ^ "Ability Magazine: Greg Louganis Interview" (2010)". Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ^ Cooper, Chet (October–November 2010), "Don't Ask(We Asked), Don't Tell(We Told)", ABILITY Magazine

- ^ "The Foundation - Princess Charlene of Monaco foundation". December 26, 2018. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018.

- ^ Greg Louganis auctioning 3 of his Olympic medals to help AIDS services center

- ^ a b Jones, Grahame L. (March 29, 1989). "Louganis, Ex-Agent in Dispute : Olympic Diver Says in Court Papers He Feared for His Life". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Symons, Caroline (2010). The Gay Games: A History. Routledge. ISBN 9781134027897.

- ^ "Greg Louganis Engaged to Johnny Chaillot". Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Greg Louganis Marries Johnny Chaillot". Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Olympian Greg Louganis and Johnny Chaillot Split After 8 Years of Marriage". June 19, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (March 17, 2012). "WonderCon 2012: Prometheus Panel Recap Featuring Sir Ridley Scott and Damon Lindelof". Collider.com. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin (November 17, 2011). "Michael Fassbender's 'Prometheus' Character Inspired By... Greg Louganis?". MTV Movies Blog. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ^ "Back on Board: Greg Louganis". HBO. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ "CALIFORNIA SPORTS HALL OF FAME CELEBRATES. CLASS OF 2013. INDUCTION CEREMONY. SUNDAY, JUNE 9/ Press release. California Sports Hall of Fame. June 9, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2017" (PDF). Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "National Gay & Lesbian Sports Hall of Fame's Inaugural Class Announced". June 18, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ http://us2.campaign-archive2.com/?u=3e2108983ef299ccbbc3502ca&id=c4f7a83950, April 13, 2015

- ^ "Max & Marcellus: [hr1]". ESPN.com. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Janet Evans, Allyson Felix and Greg Louganis Selected as 2017 Tournament of Roses Grand Marshals Archived December 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Tournament of Roses Association, November 3, 2016

- ^ Louganis, Greg (1999). For the life of your dog : a complete guide to having a dog in your life, from adoption and birth through sickness and health. Betsy Sora Siino. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-02450-7. OCLC 40693868.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Greg Louganis at the Team USA Hall of Fame (archive June 11, 2023)

- Greg Louganis at Olympics.com

- Greg Louganis at Olympic.org (archived)

- Greg Louganis at Olympedia (archive)

- Greg Louganis at IMDb

- Greg Louganis to keynote DBSA 2007 National Conference at the Wayback Machine (archived May 28, 2007)

- 1960 births

- American adoptees

- American autobiographers

- American information and reference writers

- American people of Swedish descent

- American sportspeople of Samoan descent

- Divers at the 1976 Summer Olympics

- Divers at the 1984 Summer Olympics

- Divers at the 1988 Summer Olympics

- James E. Sullivan Award recipients

- Living people

- Olympic gold medalists for the United States in diving

- Olympic silver medalists for the United States in diving

- University of California, Irvine alumni

- University of Miami alumni

- Gay memoirists

- American gay sportsmen

- People with HIV/AIDS

- American gay writers

- LGBTQ divers

- Sportspeople from El Cajon, California

- American male divers

- Participants in American reality television series

- LGBTQ rights activists from California

- American philanthropists

- LGBTQ people from California

- Medalists at the 1976 Summer Olympics

- Medalists at the 1984 Summer Olympics

- Medalists at the 1988 Summer Olympics

- World Aquatics Championships medalists in diving

- Pan American Games gold medalists for the United States in diving

- Activists from California

- Summer World University Games medalists in diving

- Divers at the 1979 Pan American Games

- Divers at the 1983 Pan American Games

- Divers at the 1987 Pan American Games

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- FISU World University Games gold medalists for the United States

- Playgirl Men of the Month

- Medalists at the 1983 Summer Universiade

- Medalists at the 1979 Pan American Games

- Medalists at the 1983 Pan American Games

- Medalists at the 1987 Pan American Games

- American activists with disabilities

- American writers with disabilities

- 21st-century American male actors

- American male television actors

- American male stage actors

- Sportspeople with dyslexia

- Actors with dyslexia

- 20th-century American sportsmen