Green River (Colorado River tributary)

| Green River Seeds-kee-dee-Agie | |

|---|---|

The Green River near Canyonlands National Park | |

Green River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Wyoming, Colorado, Utah |

| Cities | Green River, Wyoming, Green River, Utah |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Wind River Mountains |

| • location | Wyoming |

| • coordinates | 43°09′13″N 109°40′18″W / 43.15361°N 109.67167°W[1] |

| Mouth | Colorado River |

• location | Canyonlands National Park, San Juan County, Utah |

• coordinates | 38°11′21″N 109°53′07″W / 38.18917°N 109.88528°W[1] |

| Length | 730 mi (1,170 km) |

| Basin size | 48,100 sq mi (125,000 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Green River, Utah[2] |

| • average | 6,121 cu ft/s (173.3 m3/s)[2] |

| • minimum | 380 cu ft/s (11 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 68,100 cu ft/s (1,930 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Blacks Fork, Henrys Fork, Duchesne River, Price River, San Rafael River |

| • right | New Fork River, Big Sandy River, Yampa River, White River |

| Type | Wild, Scenic, Recreational |

| Designated | March 12, 2019[3] |

The Green River, located in the western United States, is the chief tributary of the Colorado River. The watershed of the river, known as the Green River Basin, covers parts of the U.S. states of Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. The Green River is 730 miles (1,170 km) long, beginning in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming and flowing through Wyoming and Utah for most of its course, except for a short segment of 40 miles (64 km) in western Colorado. Much of the route traverses the arid Colorado Plateau, where the river has carved some of the most spectacular canyons in the United States. The Green is slightly smaller than Colorado when the two rivers merge but typically carries a larger load of silt. The average yearly mean flow of the river at Green River, Utah is 6,121 cubic feet (173.3 m3) per second.[2]

The status of the Green River as a tributary of the Colorado River came about mainly for political reasons. In earlier nomenclature, the Colorado River began at its confluence with the Green River. Above the confluence, Colorado was called the Grand River. In 1921, U.S. Representative Edward T. Taylor of Colorado petitioned the Congressional Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce to rename the Grand River as the Colorado River. On July 25, 1921, the name change was made official in House Joint Resolution 460 of the 66th Congress, over the objections of representatives from Wyoming and Utah and the United States Geological Survey, which noted that the drainage basin of the Green River was more extensive than that of the Grand River,[4] although the Grand carried a higher volume of water at its confluence with the Green.

The Green River is the subject of the song "Green River" by C.W. McCall.

Description

[edit]

The headwaters of the Green River is in western Wyoming, in northern Sublette County, on the western side of the Continental Divide in the Wind River Range and the Bridger–Teton National Forest. It flows south through Sublette County and western Wyoming in an area known as the Upper Green River Valley, then southwest and is joined by the Big Sandy River in western Sweetwater County. At the town of La Barge, it flows into Fontenelle Reservoir, formed by Fontenelle Dam. Below the dam, it flows through open sage-covered rolling prairie where it is crossed by the Oregon, California and Mormon emigration trails, and then further south past the town of Green River, Wyoming and into the Flaming Gorge Reservoir in southwestern Wyoming, formed by the Flaming Gorge Dam in northeastern Utah. Before the reservoir's creation, the Blacks Fork joined the Green River south of the town of Green River, but today the mouth of Blacks Fork is submerged by the reservoir.

South of the dam, it is forced to turn sharply eastward by the uplift of the Uinta Mountains, looping around the eastern tip of the range as it travels from Utah into northwestern Colorado and through Browns Park before turning west and then south into Dinosaur National Monument, where it passes through the Canyon of the Lodore (otherwise known as the Gates of Lodore) and is joined by the Yampa River at Steamboat Rock. It turns westward back into Utah along the southern edge of the Uintas in Whirlpool Canyon. In Utah, it meanders southwest across the Yampa Plateau and through the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation and the Ouray National Wildlife Refuge. Two miles south of Ouray, Utah, it is joined by the Duchesne River, and three miles (5 km) farther downstream by the White River. Ten miles farther downstream, it is joined by the Willow River.

South of the plateau, it is joined by Nine Mile Creek, then enters the Roan Cliffs where it flows south through the back-to-back Desolation and Gray canyons, with a combined length of 120 mi (192 km). In Gray Canyon, it is joined by the Price River. South of the canyon, it passes the town of Green River, Utah and is joined by the San Rafael River in southern Emery County. In eastern Wayne County it meanders through Canyonlands National Park, where it joins Colorado.[5]

The Flaming Gorge Dam in Utah is a significant regional source of water for irrigation and mining, as well as for hydroelectric power. Begun in the 1950s and finished in 1963, it was highly controversial and opposed by conservationists. Originally, a dam was to be built in Whirlpool Canyon, but the conservationist movement traded the Flaming Gorge Dam for halting that proposal.

The Green is a large, deep, powerful river. It ranges from 100 to 300 feet (30 to 100 m) wide in the upper course and from 300 to 1,500 feet (91 to 457 m) wide in its lower course, and from 3 to 50 feet (0.91 to 15.24 m) in depth. It is navigable by small craft throughout its course and by large motorboats upstream to Flaming Gorge Dam. Near the areas where the Oregon Trail crosses the river, it is 400 to 500 feet (120 to 150 m) wide and averages about 20 feet (6.1 m) deep at normal flow.

History

[edit]

Archaeological evidence indicates that the tributary canyons and sheltered areas in the river valley were home to the Fremont Culture, which flourished from the 7th century to the 13th century. The Fremont were semi-nomadic people who lived in pithouses and are best known for the rock art on canyon walls and in sheltered overhangs.

In later centuries, the river basin was home to the Shoshone and Ute peoples, both nomadic hunters. The Shoshone inhabited the river valley north of the Uinta Mountains, whereas the Utes lived to the south. The current reservation of the Utes is in the Uintah Basin. The Shoshone called the river the Seeds-kee-dee-Agie, meaning "Prairie Hen River."[6]

In 1776, the Spanish friars Silvestre Vélez de Escalante and Francisco Atanasio Domínguez crossed the river near present-day Jensen, naming it the Rio de San Buenaventura. The map-maker of the expedition, Captain Bernardo Miera y Pacheco, erroneously indicated that the river flowed southwest to what is now known as Sevier Lake. Later cartographers extended the error, representing the Buenaventura River as flowing into the Pacific Ocean. At least one charted the Buenaventura as draining the Great Salt Lake. Later, Spanish and Mexican explorers adopted the name Rio Verde, meaning "Green River" in Spanish. Exactly when the Spanish started using this name and why is unknown. Explanations of the name "Green" include ideas about the color of the water (though it is usually just as red as that of the Colorado), the color of soapstone along its banks, the color of the vegetation, and the name of a trapper. No explanation can be verified.[6] Wilson Hunt of John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company called it The Spanish River in 1811.[7] By that time it was clear to the trappers that Miera's map[8] (if they had seen it) was wrong, for they had learned from the Native Americans that the Green River drained to the Colorado River and the Gulf of California. When Jedediah Smith reached the lower Colorado in 1826, he first called it the Seedskeedee, as the Green/Colorado River was commonly known among the trappers. By the time of Bonneville's expedition in 1832, the names "Seeds-kee-dee", "Spanish River", "Green River", and even "Colorado River" were used interchangeably by the trappers and American explorers.[9]

While it was known that the Green River drained to Colorado, the exact course was not known. Miera's map showed the Colorado River branching into two major streams – the Nabajoo (San Juan) and the Zaguananas. It also showed the Zaguananas branching into four heads, including the Dolores and the Rafael (the latter of which Escalante's journal equates with Colorado per information from the Native Americans).[10] A map of 1847 redirects the course of the Rafael to the north and labels it as Green River.[11] It would be some time before the true confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers would be known.

The Old Spanish Trail from New Mexico to California crossed the river just above the present-day town of Green River, Utah.

In the early 19th century, the upper river in Wyoming was part of the disputed Oregon Country. It was explored by trappers from the North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company, such as Donald Mackenzie who pioneered the area from 1819. In 1825, the American William Ashley and a party of American explorers floated down the river from north of the Uintah Mountains to the mouth of the White River. The valley of the river became increasingly used as a wintering ground for American trappers in the next decades, with trading posts established at the mouth of the White near Whiterocks, Utah, and Browns Park. The Upper Green River Rendezvous Site near Pinedale, Wyoming was a popular location for annual mountain man rendezvous during the 1820s and 1830s, with as many as 450 to 500 trappers attending during its heyday in the 1830s.

The region was explored by John C. Fremont on several of his expeditions in the 1840s. Fremont corrected the cartographic error of Miera, establishing firmly that the river did not drain the Great Salt Lake. In 1869, the river was surveyed and mapped by John Wesley Powell as part of the first of his two expeditions to the region. During his two voyages in 1869 and 1871, he and his men gave most of the current names of the canyons, geographic features, and rapids along the river. For example, "we sweep around another great bend to the left, making a circuit of nine miles, and come back to a point within 600 feet of the beginning of the bend. In the two circuits, we describe almost in figure 8. The men call it a `bowknot' of a river; so we name it Bowknot Bend." (Powell, 1869)

From the 1840s through the 1860s, hundreds of thousands of emigrants made their way west along the Oregon, California, and Mormon emigration trails. Nearly all primary emigration routes had to cross the Green River. The main trail crossed near where the Big Sandy River joins the Green River in Wyoming. The river is too big and much too deep to ford at any time of the year and is the largest, most dangerous river crossed by the Oregon Trail. For that reason, ferries were commonly run on this stretch of the river. Some popular ferries included the Lombard and Robinson ferries at the main crossing and the Mormon, Mountain Man, and Names Hill ferries where the popular Sublette-Greenwood cutoff crossed the river further upstream.

In 1878 the first permanent settlement in the river valley was founded at Vernal by a party of Mormons led by Jeremiah Hatch. The settlement survived a diphtheria epidemic its first winter, as well as a panic caused by the Meeker Massacre in Colorado.

Most of the land in the valley of the river today is owned and controlled by the federal government. Private holdings are largely limited to bottoms. Until the 1940s, the valley's economy was based largely on ranching. Tourism has emerged as the dominant industry in the region in the last several decades.

A proposed nuclear power plant, the Blue Castle Project, is set to begin construction near Green River in 2023.[12] The plant will use 53,500 acre-feet (66,000,000 m3) of water annually from the Green River once both reactors are commissioned.

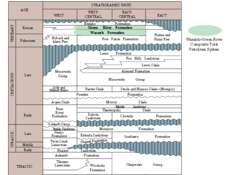

Natural resources

[edit]The La Barge oil field was discovered in 1924. Oil was produced from Tertiary sandstones (Wasatch Formation and Green River Formation), within an anticline 600 to 1200 feet deep. The Big Piney-La Barge complex has produced gas since 1956 and oil since 1960. Cumulative production by 1976 was 65 million bbl of oil and over 1.2 Tcf (trillion cubic feet) of gas. Production includes the Cretaceous Mesaverde Formation and Frontier Formation.[13]

The discovery of petroleum at the Ashley Field after World War II has led to the exploitation of oil and natural gas in the region. The oil at Ashley Field is trapped in Aeolin deposits of "coversands and loess," while there is a larger deposit of oil shale in the Green River formation.[14][15] The Equity Oil Company currently has 17 wells in declining production of oil near Ashley Field and is looking to inject carbon dioxide[16] into the Weber reservoir to increase the rate of oil flow through their pipelines.[17]

At the time of its discovery (2005), the Green River Formation was said to have the world's largest fossil fuel deposits in the form of a solid rock resource called[18] oil shale. There is estimated to be between 500 billion and 1.1 trillion barrels (80 and 175 km3) of potentially recoverable oil in the basin,[19] however; this estimated amount of recoverable oil in the form of kerogen is challenged, and in doubt, as currently there is no economically feasible technology to convert rock into a permeable oil. Kerogen is an uncooked form of hydrocarbon that nature did not convert into actual oil.[20] The cost of converting Green River oil shale into actual oil at the moment would be higher than what it could be sold for. The EROI for oil shale is very low while having a very high destructive environmental impact.[21]

The Green River Basin contains the world's largest known deposit of trona ore near Green River, Wyoming. Soda ash mining from trona veins 900 and 1600 feet (300 and 500 m) deep is a major industrial activity in the area, employing over 2000 persons at four mines. The mining operation is less expensive for the production of soda ash in the United States than the synthetic Solvay process, which predominates in the rest of the world.[citation needed]

The area has been mined for uranium.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Green River

- ^ a b c Michael Enright; D.E. Wilberg; J.R. Tibbetts (April 2005). "Water Resources Data, Utah, Water Year 2004". U.S. Geological Survey: 120. Retrieved January 20, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Explore Designated Rivers". Rivers.gov. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ Many years ago, the Colorado River was just Grand, retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ GEOLOGIC STORY of UINTA MOUNTAINS By Wallace R. Hansen, GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1291. Library of Congress catalog-card No. GS 68-327, 1983

- ^ a b Webb, Roy (1994), "The Green River", Utah History Encyclopedia, University of Utah Press, ISBN 9780874804256, archived from the original on November 3, 2022, retrieved May 6, 2024

- ^ "Seeds-Kee-Dee-Agie - Wyoming Historical Markers on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ An image of Miera's map is viewable at the Wikipedia site for Buenaventura River (legend)

- ^ "University of Wyoming". Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- ^ Escalante's Journal Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine September 5

- ^ "Mapa de los Estados Unidos de Méjico : segun lo organizado y definido por las varias actas del congreso de dicha républica y construido por las mejores autoridades". Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ Stoddard, Patsy (January 24, 2017). "Update on the Nuclear Power Plant for Green River". Castle Dale, Utah: Emery County Progress. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ McDonald, Robert (1976). Braunstein, Jules (ed.). Big Piney-La Barge Producing Complex, Subtlette and Lincoln Counties, Wyoming, in North American Oil and Gas Fields. Tulsa: The American Association of Petroleum Geologists. pp. 91–120. ISBN 0891813004.

- ^ Law, Matt. "Aeolin Deposits". The Wiki Archeological Information Resource.

- ^ Eastney (2004). "Geoarcheology: Using Earth Sciences to Understand the Archeological Record". English Heritage Center for Archeology.

- ^ "Greenhouse Gas Emissions". EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ^ Sutliff Johansson, Stacy. "Ashley Field Petroleum". Prezi. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ Shell's Ingenious Approach to Oil Shale Archived September 10, 2005, at the Wayback Machine Rocky Mountain News September 3, 2005

- ^ Study Reveals Huge U.S. Oil-shale Field Seattle Times September 1, 2005

- ^ Nelder, Chris. "The Last Sip". Smart Planet. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- ^ Cleveland, Cutler J.; o'Connor, Peter A. (2011). "Energy Return on Investment (EROI) of Oil Shale". Sustainability. 3 (11): 2307–2322. doi:10.3390/su3112307.

External links

[edit]- The Green River Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Green River Headwaters: Green River Lakes Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Official Stream-Flow and Water-Supply Forecasts

- Green River (Colorado River tributary)

- Tributaries of the Colorado River

- Rivers of Colorado

- Rivers of Utah

- Rivers of Wyoming

- Rivers of the Rocky Mountains

- Tributaries of the Colorado River in Colorado

- Tributaries of the Colorado River in Utah

- Tributaries of the Colorado River in Wyoming

- Colorado Plateau

- Rivers of Carbon County, Utah

- Rivers of Emery County, Utah

- Rivers of Moffat County, Colorado

- Rivers of San Juan County, Utah

- Rivers of Sublette County, Wyoming

- Rivers of Sweetwater County, Wyoming

- Rivers of Uinta County, Wyoming

- Rivers of Uintah County, Utah

- Rivers of Wayne County, Utah

- Tributaries of the Green River (Colorado River tributary)

- Rivers of Lincoln County, Wyoming

- Rivers of Grand County, Utah

- Rivers of Daggett County, Utah

- Wild and Scenic Rivers of the United States