Greater Netherlands

Greater Netherlands | |

|---|---|

| |

| Area | |

• Total | 55,490 km2 (21,420 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 24,562,743a[1][2] |

• Density | 460/km2 (1,191.4/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | €1.289 trilliona[3] |

| |

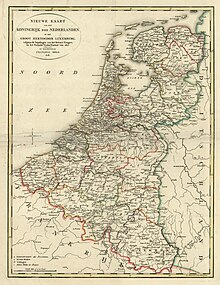

Greater Netherlands (Dutch: Groot-Nederland, pronounced [ˌɣroːt ˈneːdərlɑnt]) is an irredentist concept which unites the Netherlands, Flanders, and sometimes Brussels. Additionally, a Greater Netherlands state may include the annexation of the French Westhoek, Suriname, formerly Dutch-speaking areas of Germany and France, or even the ethnically Dutch and/or Afrikaans-speaking parts of South Africa.[4] A related proposal is the Pan-Netherlands concept, which includes Wallonia and potentially also Luxembourg.

The Greater Netherlands concept was originally developed by Pieter Geyl,[5] who argued that the "Dutch tribe", encompassing the Flemish and Dutch people, only separated due to the Eighty Years' War against Spain in the 16th century.[6] While Geyl—an outspoken anti-fascist—argued from a historical and cultural perspective, the fascist Verdinaso and Nazi movements built upon the idea of a Greater Netherlands during the 1930s and 1940s with a focus on ethnic nationalism, a concept still prominent among some on the far-right. Other 21st-century proponents of the Greater Netherlands concept include moderates in Belgium and the Netherlands who seek to elevate the Benelux ideal to a more centralized political union.[7]

Public support for a union of Flanders and the Netherlands is relatively small, especially in Flanders, where Flemish independence is seen as the main alternative to the Belgian state.

Economy

[edit]Greater Netherlands without Brussels:

| Area km2 | Population (2022) |

GDP (2022)[3] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41,865 | 17,933,600 | €958.549 billion | |

| 13,625 | 6,629,143 | €330.495 billion | |

| Greater Netherlands | 55,490 | 24,562,743 | €1.289 trillion |

Or with Brussels:

| Area km2 | Population (2022) |

GDP (2022)[3] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 162 | 1,222,657 | €96.513 billion | |

| 41,865 | 17,933,600 | €958.549 billion | |

| 13,625 | 6,629,143 | €330.495 billion | |

| Greater Netherlands | 55,652 | 25,785,400 | €1.386 trillion |

Terminology

[edit]The potential country is also known as Dutchland (Dietsland), which incorporates the word Diets – an archaic term for (Middle) Dutch. This label was popular until the Second World War, but its associations with collaboration (especially in Flanders) meant that modern supporters generally avoid using it.[8] The ideology is often labeled as Greater Netherlandism (Groot-Nederlandisme). Dutch Movement[9] (Dietse Beweging) is another term often used for the movement, while in literature it is often called the Greater Netherlands Thought (Grootnederlandse Gedachte).[5]

Greater Netherlandism is often confused with the Orangist movement in Belgium which fought for the reunification of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands after Belgian Independence. While many Orangists are Greater Netherlandists, the Orangists mainly focus on restoring Orange-Nassau's control over the South often for legitimist reasons.[10]

The Prince's Flag is sometimes used by both Orangist and Greater Netherlandic groups due to its use by supporters of William I of Orange during the Eighty Years' War, who led the revolt of the Low Countries against the Spanish. During this rebellion the Dutch-speaking regions of the Low Countries, encompassing modern day Flanders and the Netherlands, banded together under the Union of Utrecht, the precursor to the modern Dutch state. The flag was also used by the Dutch Republic and United Kingdom of the Netherlands. Today the flag is generally associated with the far-right in the Netherlands.

Pan-Netherlands

[edit]"Pan-Netherlands" (Dutch: Heel-Nederland) is another term that was used for the theoretical Greater Netherlands state,[11] but this term is now used mainly for the movement that aims to unite all of the Low Countries (Benelux) as a single multilingual entity, also including Wallonia and Luxembourg.[9]

History

[edit]

The first proposals to unite the Southern Netherlands with the Dutch Republic to form a greater Dutch-speaking state were made following the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789.[12] The concept was realized following the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 when the Congress of Vienna established the Kingdom of the Netherlands from the territories of the former Dutch Republic and Austrian Netherlands. Following the independence of Belgium in 1830, the 1860s saw renewed Flemish interest in a united Dutch-speaking state as some Dutch-speaking Belgian citizens opposed the privileged positions held by the French-speaking bourgeoisie.[13] By the end of the 19th century the Greater Netherlandic movement had emerged alongside the Flemish Movement in response to the subordination of the Dutch-speaking population in Belgian government and public life. 'Waar Maas en Schelde vloeien' (also known as 'Het Lied der Vlamingen') is a popular Greater Netherlandic song written around this time by Peter Benoit and Emmaniel Hiel.[14] In 1895 nationalists from both Belgian Flanders and the Netherlands created the Greater Netherlandic General Dutch Union (Dutch: Algemeen-Nederlands Verbond (ANV)) for the purpose of stimulating cooperation between Belgian Flanders and the Netherlands, a role it continues to hold.[15]

The German occupation of Belgium during World War I further intensified the conflict between the nation's Walloon and Flemish communities. Seeing the linguistic division of Belgium as a means of facilitating its occupation, the Germans employed Flamenpolitik to divide the administration of Belgium between French and Dutch-speaking authorities.[16][17] This resulted in a surge in the popularity of the ANV in both Flanders and the Netherlands, with a group of more radical students founding the Dutch Student Association (Dutch: Dietsch Studentenverbond).[18][19][20] Even the BWP—the first Belgian socialist party—had a considerable number of Greater Netherlandists among their ranks in Antwerp, including Maurits Naessens.[21]

The Greater Netherlands idea gained more structure in the early 20th century. In the Netherlands, some nationalists began to see Flanders as part of a broader Dutch identity, and this perspective found sympathy in Flemish nationalist circles, where people advocated for the preservation and promotion of the Dutch language.

During World War I (1914–1918), some Flemish nationalists saw an opportunity to push their cause by collaborating with the German occupation, which had a policy of encouraging Flemish autonomy as a way to weaken Belgium. The collaboration led to the rise of radical Flemish nationalism, some of which began to promote the idea of a union with the Netherlands.

After the war, the Flemish Movement grew in Belgium, with demands for linguistic equality and greater autonomy for Flanders. While this movement was primarily focused on gaining rights within Belgium, a fringe element started advocating for full separation from Belgium and unification with the Netherlands under a "Greater Netherlands."

Occupations of Belgium and the Netherlands by Nazi Germany during World War II resulted in the belief within nationalist circles that a Greater Netherlands state could be achieved through collaboration with the German occupiers. While their administration of Belgium was divided along linguistic lines in a policy similar to Flamenpolitik, the German Nazis did not seek to combine Flanders with the Netherlands. They instead sought either the establishment of a Pan-Germanist union of the ethnically Germanic Dutch speakers with Germany or a New Order in which both Belgium and the Netherlands would continue to exist as de jure independent German satellite states.[22] The movement saw a drastic decline in popularity following the war due to its association with wartime collaborators in both countries, particularly due to the Flemish National Union (VNV) in Flanders and the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands, though remains popular among some on the right of Flemish and Dutch politics.[23]

Political parties

[edit]The Belgian far-right party Vlaams Belang voiced support for the idea, since they see the formation of a "Federation of the Netherlands" as a logical and desirable consequence of a Flemish secession from Belgium. In 2021, the leader of the Flemish Nationalist N-VA, Bart De Wever argued in Trends Talk on Kanaal Z that the next step after Belgian Confederalism should be a union of Flanders and the Netherlands,[24] which led to a resurgence in discussions on the topic.

In the Netherlands it is on the agenda of two major political parties, the far-right Party for Freedom (PVV) and Forum for Democracy (FvD). On 12 May 2008, Dutch politician Geert Wilders (PVV) said in De Telegraaf that he was interested in the possibility of unifying the Netherlands and Flanders. Wilders proposed that, in accordance with previous polls, referendums should be held in the Netherlands and Flanders on the merger.[25] He argued that he was not planning to impose unification on the Flemish, but stated that then-Dutch Prime Minister Jan-Peter Balkenende needed to discuss the subject with his Flemish colleagues, which Balkenende refused. Thierry Baudet of the far-right Forum for Democracy also voiced support saying he "welcomes" Flanders in their kingdom even arguing that Flanders "actually belongs to us" when asked about it at a conference.[26]

Smaller Greater-Netherlandic groups are the Dutch political party Nederlandse Volks-Unie (NVU) and the Belgo-Dutch Voorpost.

Opinion polling

[edit]Although it hasn't been a major political issue in the Netherlands for quite some time, in 2007, a poll indicated that two-thirds of the Dutch population would welcome a union with Flanders.[27] Another poll published by RTL4 found that 77% of respondents living in the Netherlands would support a Greater Netherlands.[28]

In Flanders, support for the idea is less clear. A 1999 study by Jaak Billiet of the Catholic University of Leuven showed that 1 to 2% of Flemish people were in favor of the idea. Non-representative opinion polls on the internet have since proven less clear, with between 2% and 51% of respondents supporting unification with the Netherlands.[29] While the prevailing Dutch view on unification is it being a means of territorial expansion, the Flemish have expressed fears of being culturally assimilated into the larger and more populous Netherlands.

Although, due to the difficulties experienced in the 2007 Belgian government formation and to a lesser extent during the 2019–2020 Belgian government formation and the victory of both Flemish separatist parties; New Flemish Alliance and Vlaams Belang, in those elections, the discussion on Flanders seceding from Belgium became relevant again. Neither of the separatist parties openly supports a "Greater Netherlands" however, presidents of both parties (Tom Van Grieken and Bart De Wever) spoke out in favour of a Greater Netherlands after Flemish independence.[30][24]

See also

[edit]- Bakker Schut Plan

- Benelux

- Burgundian Netherlands

- Flemish movement

- Hypothetical partition of Belgium

- Low Countries

- Orangism

- Rattachism – a similar movement in Wallonia aiming for unification with France

- Seventeen Provinces

- Union of Utrecht

- United Kingdom of the Netherlands

References

[edit]- ^ "Structuur van de bevolking | Statbel". statbel.fgov.be. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ^ "Bevolkingsteller". Statistics Netherlands (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". www.ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Groot-Nederlandse gedachte" (in Dutch). Network of War Collections. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ a b Geyl, Pieter (1930). De Groot-Nederlandsche gedachte. Historische en politieke beschouwingen (in Dutch).

- ^ Geyl, Pieter. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Stam. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ van der Kwast, Ricus (17 July 2019). "Een verenigde Benelux zal een machtsfactor van jewelste blijken. En zal als cement en katalysator voor de EU fungeren". De Morgen. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Bruning, Henri (1954–1955). Maatstaf. Jaargang 2 (in Dutch). p. 436.

- ^ a b Waltmans, H. J. G. (1962). "De Nederlandse politieke partijen en de nationale gedachte" (PDF). Tilburg University (in Dutch): 121. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Orangisme in België: het geheimschrift ontcijferd". www.apache.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Vandenbosch, A. (6 December 2012). Dutch Foreign Policy Since 1815: A Study in Small Power Politics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 152. ISBN 978-94-011-6809-0.

- ^ J. C. H. Blom; Emiel Lamberts, eds. (2006). History of the Low Countries (New ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-84545-272-0. OCLC 70857697.

- ^ DBNL. "Bijdragen en Mededelingen van het Historisch Genootschap. Deel 76 · dbnl". DBNL (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Benoit, Peter | Studiecentrum voor Vlaamse Muziek". www.svm.be. Retrieved 4 July 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Boeva, Luc (1 January 1996). "Recensie van: Tussen cultuur en politiek: Het Algemeen-Nederlands Verbond 1895-1995 / P. van Hees en H. De Schepper (red.) (1995)". WT. Tijdschrift over de Geschiedenis van de Vlaamse Beweging (in Dutch). 55 (3): 215–218. doi:10.21825/wt.v55i3.13112. ISSN 0774-532X. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Rash, Felicity; Declercq, Christophe (2 July 2018). The Great War in Belgium and the Netherlands: Beyond Flanders Fields. Springer. p. 88. ISBN 978-3-319-73108-7.

- ^ De Schaepdrijver, Sophie (1997). De Grote Oorlog (in Dutch). Antwerp, Amsterdam: Atlas.

- ^ "Algemeen-Nederlands Verbond (ANV) - NEVB Online". nevb.be. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Vandenbosch, A. (6 December 2012). Dutch Foreign Policy Since 1815: A Study in Small Power Politics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 152. ISBN 978-94-011-6809-0. Archived from the original on 3 August 2024. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Dietsch Studentenverbond (DSV) — Universiteit Gent". 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "Samen voor democratie en socialisme … Of toch niet helemaal? Verhouding tussen de Vlaamsgezinde vleugel van de Belgische Werkliedenpartij en de Internationale Socialistische Anti-Oorlogsliga in de jaren 1930. | Scriptieprijs". www.scriptiebank.be. Archived from the original on 3 August 2024. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ DBNL. "Maurice de Wilde, België in de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Deel 3 · dbnl". DBNL (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 19 March 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Verplancke, Marnix (26 July 2015). "Groot-Nederland is 'uit'". Trouw (in Dutch). Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Reunify Flanders and the Netherlands, argues Bart De Wever". The Brussels Times. 21 July 2021. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Nederland en Vlaanderen horen bij elkaar". NRC (in Dutch). 7 July 2008. Archived from the original on 3 August 2024. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Baudet over Groot-Nederland, 25 May 2018, archived from the original on 12 December 2021, retrieved 4 July 2021

- ^ "Dutch Would Reunify with Belgium's Flanders." Archived 7 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine Angus Reid Global Monitor. 25 August 2007. Accessed 10 January 2008.

- ^ "Nederlanders massaal voor fusie met Vlaanderen". Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "Regional inequalities and localist movements" (PDF). Econstor.eu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Tom van Grieken over het herenigen van De Nederlanden, 24 October 2019, archived from the original on 12 December 2021, retrieved 4 July 2021

Further reading

[edit]- Ham, L.J. Voeten vegen: Eenheid en verschil in het grootnederlandse discours van De Toorts (1916-1921) Archived 9 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine (2008)