Magnum opus (alchemy)

In alchemy, the Magnum Opus or Great Work is a term for the process of working with the prima materia to create the philosopher's stone. It has been used to describe personal and spiritual transmutation in the Hermetic tradition, attached to laboratory processes and chemical color changes, used as a model for the individuation process, and as a device in art and literature. The magnum opus has been carried forward in New Age and neo-Hermetic movements which sometimes attached new symbolism and significance to the processes. The original process philosophy has four stages:[1][2]

- nigredo, the blackening or melanosis

- albedo, the whitening or leucosis

- citrinitas, the yellowing or xanthosis

- rubedo, the reddening, purpling, or iosis

The origin of these four phases can be traced at least as far back as the first century. Zosimus of Panopolis wrote that it was known to Mary the Jewess.[3] The development of black, white, yellow, and red can also be found in the Physika kai Mystika of Pseudo-Democritus, which is often considered to be one of the oldest books on alchemy.[4] After the 15th century, many writers tended to compress citrinitas into rubedo and consider only three stages.[5] Other color stages are sometimes mentioned, most notably the cauda pavonis (peacock's tail) in which an array of colors appear.

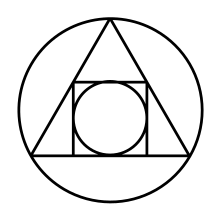

The magnum opus had a variety of alchemical symbols attached to it. Birds like the raven, swan, and phoenix could be used to represent the progression through the colors. Similar color changes could be seen in the laboratory, where for example, the blackness of rotting, burnt, or fermenting matter would be associated with nigredo.

Expansion on the four stages

[edit]Alchemical authors sometimes elaborated on the three or four color model by enumerating a variety of chemical steps to be performed. Though these were often arranged in groups of seven or twelve stages, there is little consistency in the names of these processes, their number, their order, or their description.[6]

Various alchemical documents were directly or indirectly used to justify these stages. The Tabula Smaragdina is the oldest document[7] said to provide a "recipe". Others include the Mutus Liber, the twelve keys of Basil Valentine, the emblems of Steffan Michelspacher, and the twelve gates of George Ripley.[8] Ripley's steps are given as:[9]

| 1. Calcination | 7. Cibation |

| 2. Solution (or Dissolution) | 8. Sublimation |

| 3. Separation | 9. Fermentation |

| 4. Conjunction | 10. Exaltation |

| 5. Putrefaction | 11. Multiplication |

| 6. Congelation | 12. Projection |

In another example from the sixteenth century, Samuel Norton gives the following fourteen stages:[10]

| 1. Purgation | 8. Conjunction |

| 2. Sublimation | 9. Putrefaction in sulphur |

| 3. Calcination | 10. Solution of bodily sulphur |

| 4. Exuberation | 11. Solution of sulphur of white light |

| 5. Fixation | 12. Fermentation in elixir |

| 6. Solution | 13. Multiplication in virtue |

| 7. Separation | 14. Multiplication in quantity |

Some alchemists also circulated steps for the creation of practical medicines and substances, that have little to do with the magnum opus. The cryptic and often symbolic language used to describe both adds to the confusion, but it's clear that there is no single standard step-by-step recipe given for the creation of the philosopher's stone.[11]

Magnum opus in literature and entertainment

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The-Four-Stages-of-Alchemical-Work

- ^ Joseph Needham. Science & Civilisation in China: Chemistry and chemical technology. Spagyrical discovery and invention: magisteries of gold and immortality. Cambridge. 1974. p. 23

- ^ Henrik Bogdan. Western esotericism and rituals of initiation. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 197

- ^ Cavendish, Richard (1967). The Black Arts. Putnam. p. 150. ISBN 9780399500350.

- ^ "Meyrink und das theomorphische Menschenbild". Archived from the original on 2007-09-12. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- ^ Stanton J. Linden. The alchemy reader: from Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac Newton. p. 17

- ^ it is unclear if the text originates in the Middle Ages or in Late Antiquity, but it is generally assumed to predate 1150, when Gerard of Cremona translated it from the Arabic (Mircea Eliade, History of Religious Ideas, vol. 3/1)

- ^ From George Ripley's Compound of Alchymy. (1471)

- ^ Stanton J. Linden. The alchemy reader: from Hermes Trismegistus to Isaac Newton. p.17

- ^ Mark Haeffner. Dictionary of Alchemy: From Maria Prophetessa to Isaac Newton. p.238

- ^ Mark Haeffner. Dictionary of Alchemy: From Maria Prophetessa to Isaac Newton. p.237