Ludovisi Battle sarcophagus

| Ludovisi Battle sarcophagus | |

|---|---|

Relief panel of the Great Ludovisi sarcophagus | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| 41°54′04″N 12°28′22″E / 41.901194°N 12.472833°E | |

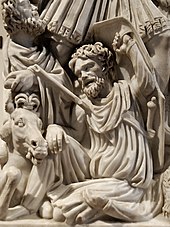

The Ludovisi Battle sarcophagus or "Great" Ludovisi sarcophagus is an ancient Roman sarcophagus dating to around AD 250–260, found in 1621 in the Vigna Bernusconi, a tomb near the Porta Tiburtina.[1] It is also known as the Via Tiburtina Sarcophagus, though other sarcophagi have been found there. It is known for its densely populated, anti-classical composition of "writhing and highly emotive"[2] Romans and Goths, and is an example of the battle scenes favored in Roman art during the Crisis of the Third Century.[2] Discovered in 1621 and named for its first modern owner, Ludovico Ludovisi, the sarcophagus is now displayed at the Palazzo Altemps in Rome, part of the National Museum of Rome as of 1901.[3]

The sarcophagus is a late outlier in a group of about twenty-five late Roman battle sarcophagi, the others all apparently dating to 170–210, made in Rome or in some cases Athens. These derive from Hellenistic monuments from Pergamon in Asia Minor showing Pergamene victories over the Gauls, and were all presumably commissioned for military commanders. The Portonaccio sarcophagus is the best known and most elaborate of the main Antonine group and shows both considerable similarities to the Great Ludovisi sarcophagus, and a considerable contrast in style and mood.[4]

Description

[edit]

The sarcophagus measures 1.53m in height and is made from Proconnesian marble, a medium characterized by dark gray stripes and a medium to coarse grain.[5] This was imported from Proconnesus and was the most common source of marble imported into Italy during the imperial period.[6] It is decorated in a very high relief with many elements of the composition cut completely free of the background. Overlapping figures entirely fill the image space, allowing no room to depict a background. In many battle sarcophagi the side panels show more tranquil scenes, but here the battle continues round both sides.

The lid of the sarcophagus has a center plaque for inscription and is flanked by two masks showing the side profile of men. Their facial features are idealized, similar to the Romans in the battle scene, but their hair and beards are untamed like the Barbarians. The inscription plaque is now blank, but was thought to be inscribed with paint.[1] The scene to the left of the plaque depicts barbarian children handed over to a Roman general by men presumably their fathers.[7] This act was referred to as clemency, where children were sometimes taken into Roman custody as pledges of peace, and might be reeducated as Romans. The right side of the lid shows a half length portrait of a woman, wearing a tunic and palla, and holding a scroll. A curtain is draped above her, being supported by two figures. The woman head is turned sharply to the right, mirroring the general in the center of the frontal panel of the sarcophagus, suggesting that she is either his wife or mother.[1] The lid was broken in 1945 while on display in Mainz.

From the left most side of the frontal panel the battle scene begins with a Roman in full military armor charging into battle. To his right is a Roman soldier who has captured a Barbarian and bound his hands, but is lifting his chin and cradling his head. This action portrays a sense of mercy between the Romans and the Barbarians who are being defeated, and presents the Roman soldier with a choice of whether to slay his opponent or act mercifully.

The central figure of the tortuous composition on the front is a young Roman military commander on horseback, presumed to represent the deceased. His face is serene, and his arm is extended confidently in a "gesture which is difficult to interpret but seems to be one of farewell".[8] He does not hold any weapon and is bareheaded, unlike the other Roman soldiers. This implies that he does not need any protection or weaponry to win the battle.[1] An X-mark on his forehead has been interpreted as the cross received by initiates into the Mithraic mysteries as a sign of the god Mithras' favor. The Mithraic religion was popular among Roman soldiers. The valor (virtus) shown by the horseman may represent real-life bravery on the battlefield, but the religious connotation of the X may suggest victory over death, a theme of mounted warriors in funerary art.[9] It could also have marked the figure as the "savior of humanity, the bringer of light to a world of tumult, and the guarantor of eternity."[1]

Although the barbaric figures are usually identified as Goths, their features are too generic to warrant any proper identification. The figures do not have any specific ethnic or racial features that would usually differentiate the groups of non-Roman barbarians. Historical context such as identification of a key figure or a specific battle being depicted in the artwork is usually how historians are able to identify barbarians. However, it is typically for these features to be lacking on privately commissioned works like sarcophagi. By the second century AD most reliefs would use a generic barbaric figure because they valued the general theme of Roman conquest over non-Roman enemies more than an accurate portrayal of the Barbarians. This practice is described by Jane Francis:[6]

For the purchaser of a battle sarcophagus, the desire to ally himself with the glories of Rome and the part that whether directly or indirectly, was more important than specific foe. This attitude would have been particularly convenient for men who had seen no significant military action but who could still claim to be part of the war machine of the empire.

The sarcophagus contains many precise depictions of military details such as the draco military standard and a detailed mail shirt of the longer length characteristic of the period.[10]

The figures towards the bottom of the scene have fallen to the ground and are mostly the Barbarians who have been slain. They lie in agony with their horses, and are trampled by the ongoing battle above them. These figures are the bottom of the relief are smaller in proportion to the humans and horses above.

Technique and style

[edit]Since the reliefs were often very deep and intricate, the sarcophagi were shipped with only a rough carving blocked out to prevent damage. The sculptor would either travel with the sarcophagi, or finish the carving in their permanent workshop in Italy.[11]

The Ludovisi sarcophagus came shortly after a trend where reliefs would be made in the same style of Marcus Aurelius' column, with very deep cutting. This was the trend of pictorial reliefs in the 2nd century. The scene on the sarcophagus depicts Roman values of heroic struggle and glorification of the hero, as well as themes of good over evil and civilized men over barbarians. The inclusion of Barbarians in the relief expresses how Romans viewed themselves as preservers of the civilization, much like the Greeks were.[12]

The undercutting of the deep relief exhibits virtuosic and very time-consuming drill work, and differs from earlier battle scenes on sarcophagi in which more shallowly carved figures are less convoluted and intertwined.[13] Describing it as "the finest of the third-century sarcophagi", art historian Donald Strong says:[8]

The faces are strikingly unclassical, and the technique of deep drilling is particularly obvious in the manes of the horses and the shaggy hair of the barbarians. But the main difference [to the Portonaccio sarcophagus, a similar 2nd-century work] is in the symbolism. The barbarians all seem frozen in the moment before disaster and death overwhelm them; their attitudes are highly theatrical but none the less immensely expressive... The main theme is no longer the glorification of military prowess but that of transcending the struggle, presumably conveying the notion of triumph over death ... The ugliness of pain and suffering is stressed by the dishevelled hair, the tormented eyes, the twisted mouth.

The carving is so deep that the forms are almost completely offset from the background resulting in three or four layers of various figures and forms. Overlapping figures fill the image space entirely, allowing no room to depict a background. Thus, the sense of space has been eliminated, giving rise to chaos and a sense of weary, open-ended victory. The effect of movement in the scene is evident and, unlike many battle sarcophagi which have more tranquil scenes on the side panels, the battle events continue all the way around the sarcophagus. The perspective constructed is also notable, although certainly not linear.[1]

From the time of the reign of the Antonine emperors, Roman art increasingly depicted battles as chaotic, packed, single-plane scenes presenting dehumanized barbarians mercilessly subjugated by Roman military might, at a time when in fact the Roman Empire was undergoing constant invasions from external threats that led to the fall of the empire in the West.[14] Although armed, the barbarian warriors, usually identified as, are depicted as helpless to defend themselves.[15] The theme of depicting a battle between the Goths and Romans was popular in the mid second century, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius. After this period there was a transition from mythological battle scenes to historical battles where the deceased person in the sarcophagus was specifically commemorated in the relief.[12] Various aspects of the execution of the work accentuate the contrast between the Romans and the Goths. The Roman figures are all clean-shaven and wear armour and helmets, which distinguish them clearly from the Goths, who are unarmoured and wear distinctive clothing, beards, and hairstyles. The Romans are given a more noble appearance with idealized physical features which contrast with the Goths who are almost caricatures, with enlarged noses, pronounced cheekbones, and wild expressions on their faces. The alternation of light/dark accentuates the contrast between the two groups. Shadows and deep carving are mostly found in the faces and hair of the Goths whereas the smooth surface of the marble is reserved for the Romans, who are less deeply carved.

Differences in scale between the figures, though present, are far less marked than in the earlier Portonaccio sarcophagus, such that the general is only slightly larger than his troops or enemies. Nor is the general seen wearing a helmet or in actual combat, as in the earlier sarcophagi.[8] The viewer is able to discern who the general is because he is placed in the top center of the relief. He extends outwards with a raised right arm and overlaps his horse. In contrast to his wild horse, he looks very calm amongst the chaos of the scene.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Kleiner, Diana E. E. (1992). Roman sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300046316. OCLC 25050500.

- ^ a b Fred S. Kleiner, A History of Roman Art (Wadsworth, 2007, 2010, enhanced ed.), p. 272.

- ^ Christopher S. Mackay, Ancient Rome: A Military and Political History (Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 178.

- ^ Donald Strong et al., Roman Art, 1995 (2nd edn.), p. 205, Yale University Press (Penguin/Yale History of Art), ISBN 0300052936

- ^ Frances Van Keuren, Donatio Attanasio, John J. Hermann Jr., Norman Herz, and L. Peter Gromet, "Multimethod Analyses of Roman Sarcophagi at the Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome," in Life, Death and Representation: Some New Work on Roman Sarcophagi (De Gruyter, 2011), p. 181.

- ^ a b Francis, Jane (2000). "A Roman Battle Sarcophagus at Concordia University, Montreal". Phoenix. 54 (3/4): 332–337. doi:10.2307/1089062. ISSN 0031-8299. JSTOR 1089062.

- ^ Jeannine Diddle Uzzi, "The Power of Parenthood in Official Roman Art," in Constructions of Childhood in Ancient Greece and Italy (American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 2007), p. 76.

- ^ a b c Donald Strong et al., Roman Art, 1995 (2nd edn.), p. 257, Yale University Press (Penguin/Yale History of Art), ISBN 0300052936

- ^ Katherine Welch, "Roman Sculpture," in The Oxford History of Western Art (Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 51; Linda Maria Gigante, "Funerary art," in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome (Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 250–251.

- ^ Pat Southern and Karen R. Dixon, The Late Roman Army (Yale University Press, 1996), pp. 98, 126.

- ^ Kleiner, Fred S. (2010-02-04). A history of Roman art. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-495-90987-3. OCLC 436029879.

- ^ a b Mccann, Anne Marguerite. (2012). Roman sarcophagi in the metropolitan museum of art. Metropolitan Mus Of Art. ISBN 978-0-300-19332-9. OCLC 939398193.

- ^ Welch, "Roman Sculpture", in The Oxford History of Western Art, p. 41; Mackay, Ancient Rome, p. 178.

- ^ Patrick Coleman, "Barbarians: Artistic Representations", in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 371; Allan, Life, Myth, And Art In Ancient Rome, p. 52.

- ^ Coleman, "Barbarians: Artistic Representations", p. 371.

Sources

[edit]- (in Italian) Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli and Mario Torelli, L'arte dell'antichità classica, Etruria-Roma, Utet, Turin 1976.

External links

[edit]- Smarthistory: Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus

Media related to Grande Ludovisi sarcophagus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Grande Ludovisi sarcophagus at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Laocoön and His Sons |

Landmarks of Rome Ludovisi Battle sarcophagus |

Succeeded by Ecstasy of Saint Teresa |