Great Lakes refugee crisis

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2010) |

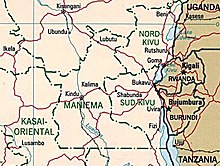

The Great Lakes refugee crisis is the common name for the situation beginning with the exodus in April 1994 of over two million Rwandans to neighboring countries of the Great Lakes region of Africa in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide. Many of the refugees were Hutu fleeing the predominantly Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), which had gained control of the country at the end of the genocide.[1] However, the humanitarian relief effort was vastly compromised by the presence among the refugees of many of the Interahamwe and government officials who carried out the genocide, who used the refugee camps as bases to launch attacks against the new government led by Paul Kagame. The camps in Zaire became particularly politicized and militarized. The knowledge that humanitarian aid was being diverted to further the aims of the genocidaires led many humanitarian organizations to withdraw their assistance.[2] The conflict escalated until the start of the First Congo War in 1996, when RPF-supported rebels invaded Zaire and sought to repatriate the refugees.[3] The conflict escalated again with the start of the Second Congo War, also called Africa's World War or the Great War of Africa, that began in 1998 when the Congolese president Laurent-Désiré Kabila turned against his former allies from Rwanda and Uganda. The conflict continues with the Kivu conflict that started in 2004 with the start of the M23 rebellion that started in 2012 and still continues today.

Background

[edit] |

| Part of a series on the |

| Rwandan genocide |

|---|

The categories Hutu and Tutsi have an origin in pre-colonial Rwanda. However, with the arrival of the Germans in about 1900, and particularly after the arrival of the Belgians in 1920, the categories began to "rigidify" and become thought of as ethnic.[4] The modern history of Rwanda has in many ways been one of tension between the majority Hutu and minority Tutsi "ethnic" groups. While there has been much scholarship about the emergence of these separate ethnic identities, particularly through the colonial governance structures, before and after independence in 1961, people within Rwanda acted within the parameters of the Tutsi-Hutu division. Regardless of the historical validity of the division, Rwandans in the late 20th century acted as if they were real.

Belgium began to withdraw from Rwanda in 1959, and in 1961 a Hutu-dominated government was established. This replaced the colonial government of Belgium, which had ruled through a favored Tutsi royal family.[5] One of the consequences of the Hutu victory was sporadic attacks against Tutsis that led to over 300,000 Tutsis fleeing the country over the next several years. Anti-Hutu attacks in neighboring Burundi by the Tutsi-led government there led a renewal in attacks against Tutsis in Rwanda in 1973, resulting in even more refugees, many seeking asylum in Uganda.[6] The land formerly owned by these thousands of refugees was subsequently claimed by others, creating another politically charged situation. By the 1980s, the Rwandan government of Juvénal Habyarimana claimed that the country could not accommodate the return of all refugees without the help of international community because Rwanda was said to be among most densely populated countries on the African continent.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Rwandan exiles formed political and military alliances, particularly in Uganda. The leader of one of these was Paul Kagame, whose family had fled to Uganda during the violence of 1959.[7] In 1985, Kagame helped form the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), an armed group aligned with the National Resistance Army (NRA), a Ugandan rebel group led by Yoweri Museveni.[8] Kagame became the head of NRA military intelligence and a close ally of Museveni. In 1986, the NRA rebellion succeeded and Museveni became President of Uganda. Museveni then supported a failed RPF invasion of Rwanda in 1990, as both a reward to an ally and in the hopes that the large Rwandan refugee population in Uganda would return home.[7] The invasion, and the subsequent occupation of parts of the northern prefectures of Byumba, Umutara and Ruhengeri, internally displaced many Hutus and heightened ethnic tensions.

The 1993 Arusha Accords attempted to offer a diplomatic solution to both the RPA threat and the internal tensions, but it was not implemented.[9] Ethnic tensions became even greater following the murder of Burundian President Melchior Ndadaye, a Hutu, in October 1993, an event that sparked the Burundian Civil War in which large numbers of both Hutus and Tutsis were killed.[10] Hutu militants, known as Interahamwe, and elements in the government in Rwanda began to plan a genocide to rid the country of the Tutsis. The assassinations of Habyarimana and Cyprien Ntaryamira on 6 April 1994 became the pretext for the start of the Rwandan genocide, which resulted in the deaths of several hundred thousand people, mostly Tutsi, over the next three months.[11] Most murders were carried out by, with the cooperation of, or in the absence of protest by Hutus who lived in the same communities as their victims.

The RPF advance and Hutu exodus

[edit]

At the beginning of the genocide in April 1994, the Rwandan Patriotic Front began an offensive from territory in northern Rwanda that it had captured in previous fighting and made rapid progress. Hutus fled the advancing RPF forces, with French historian Gérard Prunier asserting, "Most of the Hutu who had stayed in the country were there because they had not managed to run away in time."[12] In the midst of the chaos of post-genocide Rwanda, over 700,000 Tutsi refugees, some of whom had been in Uganda since 1959, began their return.[12] Contrary to refugee flows in other wars, the Rwandan exodus was not large numbers of individuals seeking safety, but a large-scale, centrally directed initiative. The refugees settled in massive camps almost directly on the Rwandan border, organized by their former leaders in Rwanda. Joël Boutroue, a senior UNHCR staff member in the refugee camps, wrote, "Discussions with refugee leaders...showed that exile was the continuation of war by other means."[12]

The result was dramatic. An estimated 500,000 Rwandans fled east into Tanzania in the month of April. On 28—29 April, 250,000 people crossed the bridge at Rusumo Falls into Ngara, Tanzania in 24 hours in what the UNHCR agency called "the largest and fastest refugee exodus in modern times".[13] The apparent organization of this Rusumo evacuation is seen as evidence that the collapsing government was behind the large refugee outflows. By May 1994, a further 200,000 people from the provinces of Butare, Kibungo and Kigali-Rural had fled south into Burundi.

As the RPF captured the capital of Kigali, the military of France set up a safe zone in southwest Rwanda in June 1994 in what was dubbed "Opération Turquoise". It was ostensibly done to stop the genocide, but the French/European forces prohibited the entry of RPF forces that were already stopping the genocide and the Hutus who fled there included militants and members of the ousted government, as well as Hutu civilians.[14] The French soon ended their intervention, leading to the flight of 300,000 people from the Zone Turquoise west towards the Zairean town of Bukavu in July and August, while a further 300,000 remained in internally displaced person camps.[15] On 18 July 1994, RPF forces captured the northwestern town of Gisenyi and declared a new government with Pasteur Bizimungu as president and Kagame in the newly created position of vice-president.[16] Gisenyi was the center of the provisional government and its fall caused over 800,000 Rwandans to cross into Goma, Zaire, over four days in late July. This outflow was also highly organized, with administrative structures simply transferred across the border.[17] By the end of August, UNHCR estimated that there were 2.1 million Rwandan refugees in neighboring countries located in 35 camps. Around Goma, the capital of North Kivu in Zaire, five huge camps—Katale, Kahindo, Mugunga, Lac Vert and Sake—held at least 850,000 people.[18] To the south, around Bukavu and Uvira, thirty camps held about 650,000 people. A further 270,000 refugees were located in nine camps in Burundi, and another 570,000 in eight camps in Tanzania.[18] The new population around Goma included 30,000 to 40,000 soldiers of the former Armed Forces of Rwanda (French: Forces Armées Rwandaises, ex-FAR), fully armed with an intact officer corps and transport unit, as well as almost all of the politicians. The only other camp complex to host significant numbers of leaders of the former government was the large Benaco camp in Tanzania, which held a small number of the exiled military and political leadership. The exiles chose to base themselves mainly in Zaire because of the support given by President Mobutu Sese Seko.[12] The five camps around Goma, among others, would eventually take on a certain permanence, eventually containing 2,323 bars, 450 restaurants, 589 shops, 62 hairdressers, 51 pharmacies, 30 tailors, 25 butchers, five ironsmiths and mechanics, four photo studios, three movie theaters, two hotels and one slaughterhouse.[12]

About 140,000 refugees returned, mostly on their own, in the first three months after the original exodus. The UNHCR was forced to halt its efforts to repatriate refugees after both their staff and the refugees were threatened by Interahamwe under the orders of the exiled leadership. However, by September 1994 rumors of violence by the RPF within Rwanda, combined with tightened control by the Hutu leadership of the camps, has drastically reduced the rate of return and eventually stopped it altogether by early 1995.[12][19]

Emergency relief

[edit]

In the first week of July, deaths among the refugee community were occurring at a rate of 600 per week, and two weeks later had reached 2000 per week as the refugee population increased and the health situation worsened. Mortality rates reached a height during a 24-hour period in late July when the death toll near Goma from cholera, diarrhea and other diseases was 7000.[20] Over 50,000 people died, mainly from a cholera epidemic that swept through the camps. The refugees near Goma were located at Mugunga on a plain of volcanic rock, which was so hard that the French troops and aid workers were unable to dig graves for the bodies that began to line roads.[21] The situation led the UN Representative to Rwanda Shahryar Khan to call the camps a "revision of hell".[22]

The international media coverage of the plight of the refugees eventually led U.S. President Bill Clinton to call it the "world’s worst humanitarian crisis in a generation" and large amounts of relief was mobilized.[23] Attention quickly focused on the refugees around Goma. Over 200 aid organizations rushed into Goma to start an emergency relief operation comparable to that seen in the Yugoslav wars.[citation needed] Until December, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) received over $1 million monthly. The resources dedicated to the refugees led to a rapid drop in the mortality rate in late 1994. The American military formed an emergency logistical operation, based out of Entebbe International Airport in Uganda, to ferry supplies and relief personnel to the crisis regions.[24] While several humanitarian organizations expressed concern about mixing the military in humanitarian operations, it quickly became clear that only the military could create large centralized logistical support with the speed and scale needed to alleviate a massive humanitarian emergency.

The humanitarian situation was not as acute in the other nations bordering Rwanda, though still very challenging. Tanzania had a number of refugee camps that had been created for the civilians fleeing the onset of the Burundian Civil War. Most of these Burundians had returned to their home country by 1994 so Tanzania had the infrastructure to handle the initial influx of Rwandan refugees. However, facilities there were also eventually overwhelmed by the sheer number of people fleeing across the border, requiring emergency humanitarian intervention.[25]

Interventions by particular nations

[edit]

The UN, in the absence of any serious military aid from the US, was forced to open its communication pathways wider than before and urge other countries to join the efforts. The US agreed to support these efforts with finance and some equipment. Early in the relief process, US relief planes began to drop large food packages from the air in hopes of alleviating the suffering in the camps below.[24] Instead, the opposite occurred, as people were slaughtered by mobs trying to reach the precious food. Due to the perils of such chaos in the refugee camps, the US refused to bring its aid closer to the ground, and, as time went by, dysentery and cholera began to spread rapidly through the crowded refugee camps, ultimately killing tens of thousands.[26] Soon, the problem was exacerbated as rain began to fall and many people contracted septic meningitis.[27]

By then, France had established a field hospital at the area of Lake Kivu in an attempt to help the large numbers of refugees.[citation needed] Some of these refugees were Interahamwe leaders and members of the government who fled the country fearing retaliation from the RPF. To aid the ground forces, Israel conducted the largest medical mission in its history, and, although their supplies were not as abundant as those of the other forces, their all-volunteer force of military surgeons was composed both of specialists and sub-specialists, including well-known surgeons.[28] The two units established a unique and constructive method of operation which relied on France's abundant medical supplies and Israel's medical expertise.

Japan was the third largest donor to the intervention:[29] Japan also deployed the Japan Self-Defense Forces assets, including the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force units for medical and water supply activities, and the Japan Air Self-Defense Force aircraft to transport personnel and supplies, including NGOs'.[30]

The Netherlands had sent a small contingent of mostly medics and nurses, which was beneficial for rehabilitation efforts and ambulatory care after patients left the French-Israeli medical quarters. CARE Deutschland supplied ambulances, and Merlin of Ireland supplied trucks and heavy equipment to distribute food and supplies to the refugee camps. The country of Germany was the sixth largest donor to the intervention, Ireland was 16th. [29]

Militarization of refugee camps

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (April 2010) |

The first goal of the political leadership was to gain control of the food supply. This was accomplished by a system of "elected popular leaders", who acted as a front for the real leaders and were able to secure control of the humanitarian aid. The leadership could punish their enemies by withholding aid, reward their supporters by giving it and even make money either by reporting more refugees than actually existed and selling the surplus or by forcing the refugees to pay a food tax. The political elite and ex-FAR soldiers were given preferential treatment.[31] This led, for example, to the otherwise curious finding of one humanitarian aid study that 40% of refugees in Kibumba camp ate less than 2,000 kcal per person, while 13% received over 10,000 kcal per person.[32] Refugees who disagreed with the structure, who tried to return to Rwanda or were too frank with aid workers in discussing the situation were subject to intimidation and murder.[33]

As the initial acute humanitarian crisis was stabilized, aid workers and others began to raise concerns about the presence of armed elements in the camps. Soldiers of the former and the Interahamwe militia created armed outposts on the outskirts of the refugee camps, while the camps themselves came under the control of officials of the former government. Humanitarian workers reported that former government officials, especially near Goma, were passing out large amount of money to the militia to control the refugees on their behalf. Those refugees who tried to protest were either beaten into submission or killed.

The relief operation began to be accused of "feeding the killers", causing a crisis of conscience among the agencies, who began to leave what some have called "the messiest humanitarian quagmire ever". The first to leave was Médecins Sans Frontières, who stated that "this humanitarian operation was a total ethical disaster" as it rewarded those responsible for the genocide rather than punishing them. The International Rescue Committee, a long-standing implementing partner of the UNHCR, then left stating that "humanitarianism has become a resource and people are manipulating it as never before. Sometimes we just shouldn’t show up for a disaster." These two organizations were joined by Oxfam, Save the Children and CARE, completing the departure of the largest and most professional humanitarian aid organizations upon which UNHCR relied heavily. A secondary reason given by some of these organizations is that they hoped that this dramatic action would prompt the international community to disarm the camps.

Despite repeated calls by the UN for international intervention to separate the armed elements from the civilians in need of assistance, there was little response. Of over 40 countries that UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros Ghali approached to provide peacekeepers, only one replied affirmatively. The UN eventually resorted to hiring Zairean soldiers to provide a minimum level of security, a situation that everyone realized was far from ideal. In light of their abandonment by its trusted partners and the insecurity, High Commissioner Sadako Ogata was asked why UNHCR did not simply leave as well. She replied:

There were also innocent refugees in the camps; more than half were women and children. Should we have said: you are related to murderers, so you are guilty, too? My mandate — unlike those of private aid agencies — obliges me to help.

Both for those organizations that left and that stayed, the post-Rwandan genocide refugee crisis became a watershed event that prompted an extensive reevaluation of their mandates and procedures, and the relative ethical cases for abandonment and continuing aid were hotly debated. At the same time, France and the World Bank withheld development aid from the new government of Rwanda until the refugees were repatriated, prompting accusations that the donors were simply repeating the cycle of poverty that had led Rwanda into crisis originally.

Effects

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (April 2010) |

The AFDL continued its offensive until it reached Kinshasa and overthrew Mobutu in 1997. Mobutu fled Zaire and soon died in exile four months later. Afterwards, Kabila named himself the new president and changed the name of the country to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, the relationship between Kabila and his Rwandan and Ugandan backers turned sour. An attempt by Rwanda and Uganda to overthrow Kabila in 1998 grew into the Second Congo War, the world's deadliest conflict since World War II. While peace was officially declared in 2003, ethnically inspired violence continues to afflict the Kivus.

Rwanda continues to struggle with the aftermath of genocide and large-scale forced migration. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and community gacaca courts exist to punish those who planned and carried out the genocide, but the scale of violence forced the Rwandan people into an occasionally uneasy coexistence. The Rwandan government has been generally credited with encouraging economic development and national reconciliation, though it has also been criticized for oppression of its critics. The crisis had a massive impact on the ecology of the region. The forests of Virunga National Park, home to the endangered mountain gorilla, were badly damaged by the demands for firewood and charcoal made by the refugees. Two years after the arrival of the refugees 105 km2 of the park's forest had been affected, of which 63 km2 had been razed.[34]

The outside world, at the time focused on the wars of the former Yugoslavia, turned its attention away from the happenings of central Africa. The exception was the international humanitarian aid community and the United Nations, for whom the Great Lakes crisis was an agonizing dilemma that has been the topic of extensive analysis and ethical arguments. As a result, UNHCR reworked its procedures to try to ensure greater international commitment in its interventions.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Rwandan Genocide - Facts & Summary - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "THE USE AND ABUSE OF REFUGEES IN ZAIRE". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ French, Howard W. (24 September 2009). "Kagame's Hidden War in the Congo". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 6 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "Rwanda Chronology, FRONTLINE, PBS". www.pbs.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "HISTORY OF RWANDA". www.historyworld.net. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Violence, Online Encyclopedia of Mass (27 June 2008). "The Burundi Killings of 1972". www.massviolence.org. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Profile: Rwanda's President Paul Kagame - BBC News". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "The Rwandan Patriotic Front (HRW Report - Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda, March 1999)". www.hrw.org. Archived from the original on 12 March 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "Rwanda: The Failure of the Arusha Peace Accords". nsarchive.gwu.edu. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Galloway, Erin. "The Conflict Between the Tutsi and Hutu". Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "The Spark That Incited Rwanda Genocide Finally Comes To Light « AlterPolitics - Progressive Blog For Politics, World Issues, Arts & Entertainment". www.alterpolitics.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Prunier 2009, pp. 4, 5, 23, 24–25, 26, 28

- ^ "Issue 110 (Crisis in the Great Lakes) - Cover Story: Heart of Darkness". UNHCR. 1 December 1997. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ "UNAMIR". www.un.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Richburg, Keith B. (20 August 1995). "NEW TIDE OF REFUGEES HEADS OUT OF RWANDA". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "From president to prison". BBC. 7 June 2004. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Bonner, Raymond (25 July 1994). "THE RWANDA DISASTER: THE REFUGEES; Some Who Fled Rwanda Return As Zaire Opens Border Crossings". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ a b Prunier 2009, pp. 24–25

- ^ For a contemporary analysis of the situation, see Rwanda and Burundi: The return home: rumours and realities, Amnesty International, 20 February 1996, p. 14-15 Archived 10 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Great Lakes Refugee Crisis". 25 April 2017. Archived from the original on 11 May 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Rwanda: How Did It Happen?". tribunedigital-baltimoresun. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ "How to Become an Expert on the Congo in Just Five Minutes a Day". Wronging Rights. 21 October 2008. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Power, Samantha (September 2001). "Bystanders to Genocide". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Lifesaving Aid for Rwanda". The New York Times. 30 July 1994. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Lorch, Donatella (1 May 1994). "Refugees Flee Into Tanzania From Rwanda". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ DROGIN, BOB (25 July 1994). "U.S. Airdrops Aid to Rwandans : Africa: First direct American assistance consists of eight pallets of food that crash-land in a hamlet. Border area is reopened and more than 1,000 refugees return home". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ Heyman, S. N.; Ginosar, Y.; Niel, L.; Amir, J.; Marx, N.; Shapiro, M.; Maayan, S. (1 March 1998). "Meningococcal meningitis among Rwandan refugees: diagnosis, management, and outcome in a field hospital". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2 (3): 137–142. doi:10.1016/s1201-9712(98)90115-1. ISSN 1201-9712. PMID 9531659.

- ^ "2BackToHomePage3". mfa.gov.il. Archived from the original on 5 July 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ^ a b Seybolt, Taylor B. (5 July 1997). "Coordination in Rwanda: The Humanitarian Response to Genocide and Civil War". Journal of Humanitarian Assistance. Archived from the original on 19 April 1998. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ Cabinet Office, ルワンダ難民救援国際平和協力業務 [International Peace Cooperation Operations for Rwandan Refugee Relief] (in Japanese), retrieved 9 May 2023

- ^ Prunier 2009, p. 25

- ^ Footnote 97, in Prunier 2009, p. 375

- ^ Prunier 2009, pp. 25–26

- ^ Henquin and Blondel, 1997

Further reading

[edit]- Prunier, Gérard (2009). Africa's World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537420-9.

- Des Forges, Alison (1999). Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda. New York: Human Rights Watch.

- Pottier, Johan (2002). Re-Imagining Rwanda: Conflict, Survival and Disinformation in the Late Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Umutesi, Marie Béatrice. Surviving the Slaughter: The Ordeal of a Rwandan Refugee in Zaire. Translated by Julia Emerson. University of Wisconsin Press, 2004. ISBN 0-299-20494-4.

- Waters, Tony (2001). Bureaucratizing the Good Samaritan. Boulder: Westview.

- Masako Yonekawa, Akiko Sugiki, ed. (2020). Repatriation, Insecurity, and Peace: A Case Study of Rwandan Refugees. Springer. ISBN 978-981-15-2850-7.

External links

[edit]- "Study 3: Humanitarian Aid and Effects" in Steering Committee of the Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda, "The International Response to Conflict and Genocide: Lessons from the Rwanda Experience", Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, March 1996

- "Refugee tide into Rwanda overwhelms aid workers", CNN, 17 November 1996

- "Heart of Darkness", Refugees Magazine, issue 110, 1997

- State of the World's Refugees 2000, Ch. 10 "The Rwandan genocide and its aftermath" (PDF), UNHCR

- "Sharing the Security Burden: Towards the Convergence of Refugee Protection and State Security", Working Paper No. 4, Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford, May 2000[dead link]

- "UNHCR’s Relief, Rehabilitation and Repatriation of Rwandan Refugees in Zaire (1994–1997)", Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, 8 April 2002

- "Mirroring Rwanda's Challenges: the refugee story", Pambazuka News, 2004

- "Conventional Wisdom and Rwanda's Genocide: An Opinion", African Studies Quarterly (1997 by Tony Waters)

- Tom Casadevall of the United States Geological Survey; "The 1994 Rwandan Refugee Crisis: Cultural Awareness in Managing Natural Disasters" (1h28m streaming video). Lecture given at University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign on vulcanology around Goma (25 September 2006)

- UN High Commission on Human Rights: "Report of the Mapping Exercise documenting the most serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law committed within the territory of the Democratic Republic of the Congo between March 1993 and June 2003", published August 2010