Gravitational energy

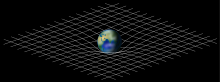

Gravitational energy or gravitational potential energy is the potential energy a massive object has due to its position in a gravitational field. It is the mechanical work done by the gravitational force to bring the mass from a chosen reference point (often an "infinite distance" from the mass generating the field) to some other point in the field, which is equal to the change in the kinetic energies of the objects as they fall towards each other. Gravitational potential energy increases when two objects are brought further apart and is converted to kinetic energy as they are allowed to fall towards each other.

Formulation

[edit]For two pairwise interacting point particles, the gravitational potential energy is the work done by the gravitational force in bringing the masses together: where is the displacement vector between the two particles and denotes the scalar product. Since the gravitational force is always parallel to the axis joining the particles, this simplifies to:

where and are the masses of the two particles and is the gravitational constant.[1]

Close to the Earth's surface, the gravitational field is approximately constant, and the gravitational potential energy of an object reduces to where is the object's mass, is the gravity of Earth, and is the height of the object's center of mass above a chosen reference level.[1]

Newtonian mechanics

[edit]In classical mechanics, two or more masses always have a gravitational potential. Conservation of energy requires that this gravitational field energy is always negative, so that it is zero when the objects are infinitely far apart.[2] The gravitational potential energy is the potential energy an object has because it is within a gravitational field.

The magnitude of the force between a point mass, , and another point mass, , is given by Newton's law of gravitation:[3]

To get the total work done by the gravitational force in bringing point mass from infinity to final distance (for example, the radius of Earth) from point mass , the force is integrated with respect to displacement:

Because , the total work done on the object can be written as:[4]

In the common situation where a much smaller mass is moving near the surface of a much larger object with mass , the gravitational field is nearly constant and so the expression for gravitational energy can be considerably simplified. The change in potential energy moving from the surface (a distance from the center) to a height above the surface is If is small, as it must be close to the surface where is constant, then this expression can be simplified using the binomial approximation to As the gravitational field is , this reduces to Taking at the surface (instead of at infinity), the familiar expression for gravitational potential energy emerges:[5]

General relativity

[edit]

In general relativity gravitational energy is extremely complex, and there is no single agreed upon definition of the concept. It is sometimes modelled via the Landau–Lifshitz pseudotensor[6] that allows retention for the energy–momentum conservation laws of classical mechanics. Addition of the matter stress–energy tensor to the Landau–Lifshitz pseudotensor results in a combined matter plus gravitational energy pseudotensor that has a vanishing 4-divergence in all frames—ensuring the conservation law. Some people object to this derivation on the grounds that pseudotensors are inappropriate in general relativity, but the divergence of the combined matter plus gravitational energy pseudotensor is a tensor.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Gravitational binding energy

- Gravitational potential

- Gravitational potential energy storage

- Positive energy theorem

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Gravitational Potential Energy". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ For a demonstration of the negativity of gravitational energy, see Alan Guth, The Inflationary Universe: The Quest for a New Theory of Cosmic Origins (Random House, 1997), ISBN 0-224-04448-6, Appendix A—Gravitational Energy.

- ^ MacDougal, Douglas W. (2012). Newton's Gravity: An Introductory Guide to the Mechanics of the Universe (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4614-5444-1. Extract of page 10

- ^ Tsokos, K. A. (2010). Physics for the IB Diploma Full Colour (revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-521-13821-5. Extract of page 143

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Richard (2006-02-02). "Gravitational potential energy". farside.ph.utexas.edu. The University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ Lev Davidovich Landau & Evgeny Mikhailovich Lifshitz, The Classical Theory of Fields, (1951), Pergamon Press, ISBN 7-5062-4256-7

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\Delta U&\approx {\frac {GMm}{R}}\left[1-\left(1-{\frac {h}{R}}\right)\right]\\\Delta U&\approx {\frac {GMmh}{R^{2}}}\\\Delta U&\approx m\left({\frac {GM}{R^{2}}}\right)h.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.riteme.site/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5118b8bff7cdd16760ce444539901d5f161d5144)