Pharyngitis

| Pharyngitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acute sore throat |

| |

| Viral pharyngitis resulting in visible redness. | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Sore throat, fever, runny nose, cough, headache, hoarse voice[1][2] |

| Complications | Sinusitis, acute otitis media[2] |

| Duration | 3–10 days, depending on cause[2][3] |

| Causes | Usually viral infection[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, rapid antigen detection test, throat swab[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Epiglottitis, thyroiditis, retropharyngeal abscess[2] |

| Treatment | lidocaine[2][4] |

| Frequency | ~7.5% of people in any 3-month period[5] |

Pharyngitis is inflammation of the back of the throat, known as the pharynx.[2] It typically results in a sore throat and fever.[2] Other symptoms may include a runny nose, cough, headache, difficulty swallowing, swollen lymph nodes, and a hoarse voice.[1][6] Symptoms usually last 3–5 days, but can be longer depending on cause.[2][3] Complications can include sinusitis and acute otitis media.[2] Pharyngitis is a type of upper respiratory tract infection.[7]

Most cases are caused by a viral infection.[2] Strep throat, a bacterial infection, is the cause in about 25% of children and 10% of adults.[2] Uncommon causes include other bacteria such as gonococcus, fungi, irritants such as smoke, allergies, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.[2][4] Specific testing is not recommended in people who have clear symptoms of a viral infection, such as a cold.[2] Otherwise, a rapid antigen detection test or throat swab is recommended.[2] PCR testing has become common as it is as good as taking a throat swab but gives a faster result.[8] Other conditions that can produce similar symptoms include epiglottitis, thyroiditis, retropharyngeal abscess, and occasionally heart disease.[2]

NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen, can be used to help with the pain.[2] Numbing medication, such as topical lidocaine, may also help.[4] Strep throat is typically treated with antibiotics, such as either penicillin or amoxicillin.[2] It is unclear whether steroids are useful in acute pharyngitis, other than possibly in severe cases, but a recent (2020) review found that when used in combination with antibiotics they moderately reduced pain and the likelihood of resolution.[9][10]

About 7.5% of people have a sore throat in any 3-month period.[5] Two or three episodes in a year are not uncommon.[1] This resulted in 15 million physician visits in the United States in 2007.[4] Pharyngitis is the most common cause of a sore throat.[11] The word comes from the Greek word pharynx meaning "throat" and the suffix -itis meaning "inflammation".[12][13]

Classification

[edit]

Pharyngitis is a type of inflammation caused by an upper respiratory tract infection. It may be classified as acute or chronic. Acute pharyngitis may be catarrhal, purulent, or ulcerative, depending on the causative agent and the immune capacity of the affected individual. Chronic pharyngitis may be catarrhal, hypertrophic, or atrophic.[citation needed]

Tonsillitis is a subtype of pharyngitis.[14] If the inflammation includes both the tonsils and other parts of the throat, it may be called pharyngotonsillitis or tonsillopharyngitis.[15] Another subclassification is nasopharyngitis (the common cold).[16]

Clergyman's sore throat or clergyman's throat is an archaic term formerly used for chronic pharyngitis associated with overuse of the voice as in public speaking. It was sometimes called dysphonia clericorum or chronic folliculitis sore throat.[17]

Cause

[edit]Most cases are due to an infectious organism acquired from close contact with an infected individual.[citation needed]

Viral

[edit]

These comprise about 40–80% of all infectious cases and can be a feature of many different types of viral infections.[11][18]

- Adenovirus is the most common of the viral causes. Typically, the degree of neck lymph node enlargement is modest and the throat often does not appear red, although it is painful.

- The family Orthomyxoviridae which cause influenza are present with rapid onset high temperature, headache, and generalized ache. A sore throat may be associated.

- Infectious mononucleosis ("glandular fever") is caused by the Epstein–Barr virus. This may cause significant lymph-node swelling and an exudative tonsillitis with marked redness and swelling of the throat. The heterophile test can be used if this is suspected.

- Herpes simplex virus can cause multiple mouth ulcers.

- Measles

- Common cold: rhinovirus, coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and parainfluenza virus can cause infection of the throat, ear, and lungs causing standard cold-like symptoms and often pain.

Bacterial

[edit]A number of different bacteria can infect the human throat. The most common is group A streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes), but others include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Bordetella pertussis, Bacillus anthracis, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Fusobacterium necrophorum.[19]

Streptococcal pharyngitis

[edit]

Streptococcal pharyngitis or strep throat is caused by a group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (GAS).[20] It is the most common bacterial cause of cases of pharyngitis (15–30%).[19] Common symptoms include fever, sore throat, and large lymph nodes. It is a contagious infection, spread by close contact with an infected individual. A definitive diagnosis is made based on the results of a throat culture. Antibiotics are useful to both prevent complications (such as rheumatic fever) and speed recovery.[21]

Fusobacterium necrophorum

[edit]Fusobacterium necrophorum is a normal inhabitant of the oropharyngeal flora and can occasionally create a peritonsillar abscess. In one out of 400 untreated cases, Lemierre's syndrome occurs.[22]

Diphtheria

[edit]Diphtheria is a potentially life-threatening upper respiratory infection caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, which has been largely eradicated in developed nations since the introduction of childhood vaccination programs, but is still reported in the Third World and increasingly in some areas in Eastern Europe. Antibiotics are effective in the early stages, but recovery is generally slow.[citation needed]

Others

[edit]A few other causes are rare, but possibly fatal, and include parapharyngeal space infections: peritonsillar abscess ("quinsy abscess"), submandibular space infection (Ludwig's angina), and epiglottitis.[23][24][25]

Fungal

[edit]Some cases of pharyngitis are caused by fungal infection, such as Candida albicans, causing oral thrush.[26]

Noninfectious

[edit]Pharyngitis may also be caused by mechanical, chemical, or thermal irritation, for example cold air or acid reflux. Some medications may produce pharyngitis, such as pramipexole and antipsychotics.[27][28]

Diagnosis

[edit]| Points | Probability of Strep | Management |

|---|---|---|

| 1 or less | <10% | No antibiotic or culture needed |

| 2 | 11–17% | Antibiotic based on culture or rapid antigen detection test |

| 3 | 28–35% | |

| 4 or 5 | 52% | Empiric antibiotics |

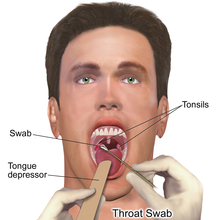

Differentiating a viral and a bacterial cause of a sore throat based on symptoms alone is difficult.[29] Thus, a throat swab often is done to rule out a bacterial cause.[30]

The modified Centor criteria may be used to determine the management of people with pharyngitis. Based on five clinical criteria, it indicates the probability of a streptococcal infection.[21]

One point is given for each of the criteria:[21]

- Absence of a cough

- Swollen and tender cervical lymph nodes

- Temperature more than 38.0 °C (100.4 °F)

- Tonsillar exudate or swelling

- Age less than 15 (a point is subtracted if age is more than 44)

The Infectious Disease Society of America recommends against empirical treatment and considers antibiotics only appropriate following positive testing.[29] Testing is not needed in children under three, as both group A strep and rheumatic fever are rare, except if they have a sibling with the disease.[29]

Management

[edit]The majority of the time, treatment is symptomatic. Specific treatments are effective for bacterial, fungal, and herpes simplex infections.

Medications

[edit]- Pain medication, such as NSAIDs and acetaminophen (paracetamol), can help reduce the pain associated with a sore throat. Aspirin may be used in adults, but is not recommended in children due to the risk of Reye syndrome.[31]

- Steroids (such as dexamethasone) may be useful for severe pharyngitis.[32][10] Their general use, however, is poorly supported.[9]

- Viscous lidocaine relieves pain by numbing the mucous membranes.[33]

- Antibiotics are useful if a bacterial infection is the cause of the sore throat.[34][35] For viral infections, antibiotics have no effect. In the United States, they are used in 25% of people before a bacterial infection has been detected.[36]

- Oral analgesic solutions, the active ingredient is usually phenol, but also less commonly benzocaine, cetylpyridinium chloride, and/or menthol. Chloraseptic and Cepacol are two examples of brands of these kinds of analgesics.[citation needed]

Alternative

[edit]Gargling salt water is often suggested, but there is no evidence to support or discourage this practice.[4] Alternative medicines are promoted and used for the treatment of sore throats.[37] However, they are poorly supported by evidence.[37]

Epidemiology

[edit]Acute pharyngitis is the most common cause of a sore throat and, together with cough, it is diagnosed in more than 1.9 million people a year in the United States.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Rutter, Paul Professor; Newby, David (2015). Community Pharmacy ANZ: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 19. ISBN 9780729583459. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Hildreth, AF; Takhar, S; Clark, MA; Hatten, B (September 2015). "Evidence-Based Evaluation And Management Of Patients With Pharyngitis In The Emergency Department". Emergency Medicine Practice. 17 (9): 1–16, quiz 16–7. PMID 26276908.

- ^ a b David A.Warrell; Timothy M. Cox; John D. Firth, eds. (2012). Oxford textbook of medicine infection. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 280–281. ISBN 9780191631733. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Weber, R (March 2014). "Pharyngitis". Primary Care. 41 (1): 91–8. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.10.010. PMC 7119355. PMID 24439883.

- ^ a b Jones, Roger (2004). Oxford Textbook of Primary Medical Care. Oxford University Press. p. 674. ISBN 9780198567820. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ Neville, Brad W.; Damm, Douglas D.; Allen, Carl M.; Chi, Angela C. (2016). Oral and maxillofacial pathology (4th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. p. 166. ISBN 9781455770526. OCLC 908336985. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ "Pharyngitis". National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ "Acute pharyngitis - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment | BMJ Best Practice". bestpractice.bmj.com.

- ^ a b Principi, N; Bianchini, S; Baggi, E; Esposito, S (February 2013). "No evidence for the effectiveness of systemic corticosteroids in acute pharyngitis, community-acquired pneumonia and acute otitis media". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 32 (2): 151–60. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1747-y. PMC 7087613. PMID 22993127.

- ^ a b de Cassan, Simone; Thompson, Matthew J.; Perera, Rafael; Glasziou, Paul P.; Del Mar, Chris B.; Heneghan, Carl J.; Hayward, Gail (1 May 2020). "Corticosteroids as standalone or add-on treatment for sore throat". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (5): CD008268. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008268.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7193118. PMID 32356360.

- ^ a b c Marx, John (2010). Rosen's emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice (7th ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Mosby/Elsevier. Chapter 30. ISBN 978-0-323-05472-0.

- ^ Beachey, Will (2013). Respiratory Care Anatomy and Physiology, Foundations for Clinical Practice,3: Respiratory Care Anatomy and Physiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 5. ISBN 978-0323078665. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Hegner, Barbara; Acello, Barbara; Caldwell, Esther (2009). Nursing Assistant: A Nursing Process Approach – Basics. Cengage Learning. p. 45. ISBN 9781111780500. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Tonsillitis". Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ Rafei K, Lichenstein R (2006). "Airway Infectious Disease Emergencies". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 53 (2): 215–242. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2005.10.001. PMID 16574523.

- ^ "www.nlm.nih.gov". Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

- ^ Broadwater, Kimberly (2021). "Clergyman's Sore Throat". Journal of Singing. 78 (1): 113–117. doi:10.53830/CNLB1302. ISSN 2769-4046. S2CID 239663449.

- ^ Acerra JR. "Pharyngitis". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ a b Bisno AL (January 2001). "Acute pharyngitis". N Engl J Med. 344 (3): 205–11. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101183440308. PMID 11172144.

- ^ Baltimore RS (February 2010). "Re-evaluation of antibiotic treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis". Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 22 (1): 77–82. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833502e7. PMID 19996970. S2CID 13141765.

- ^ a b c Choby BA (March 2009). "Diagnosis and treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis". Am Fam Physician. 79 (5): 383–90. PMID 19275067. Archived from the original on 8 February 2015.

- ^ Centor RM (1 December 2009). "Expand the pharyngitis paradigm for adolescents and young adults". Ann Intern Med. 151 (11): 812–5. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.669.7473. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00011. PMID 19949147. S2CID 207535809.

- ^ "UpToDate Inc". Archived from the original on 27 June 2009. (registration required)

- ^ Reynolds SC, Chow AW (September–October 2009). "Severe soft tissue infections of the head and neck: a primer for critical care physicians". Lung. 187 (5): 271–9. doi:10.1007/s00408-009-9153-7. PMID 19653038. S2CID 9009912.

- ^ Bansal A, Miskoff J, Lis RJ (January 2003). "Otolaryngologic critical care". Crit Care Clin. 19 (1): 55–72. doi:10.1016/S0749-0704(02)00062-3. PMID 12688577.

- ^ Harvard Medical School. "Sore Throat (Pharyngitis)". Harvard Health Publishing Harvard Medical School. Harvard Health Publishing. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ "Mirapex product insert" (PDF). Boehringer Ingelheim. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Mosby's Medical Dictionary, 8th edition". Elsevier. 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ a b c Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, Lee G, Martin JM, Van Beneden C (9 September 2012). "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 55 (10): e86–102. doi:10.1093/cid/cis629. PMC 7108032. PMID 22965026.

- ^ Del Mar C (1992). "Managing sore throat: a literature review. I. Making the diagnosis". Medical Journal of Australia. 156 (8): 572–5. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1992.tb121422.x. PMID 1565052.

- ^ Baltimore RS (February 2010). "Re-evaluation of antibiotic treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 22 (Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 22 (1)): 77–82. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833502e7. PMID 19996970. S2CID 13141765.

- ^ Hayward G, Thompson M, Heneghan C, Perera R, Del Mar C, Glasziou P (2009). "Corticosteroids for pain relief in sore throat: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 339: b2976. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2976. PMC 2722696. PMID 19661138.

- ^ "LIDOCAINE VISCOUS (Xylocaine Viscous) side effects, medical uses, and drug interactions". Archived from the original on 8 April 2010.

- ^ Kocher, JJ; Selby, TD (1 July 2014). "Antibiotics for sore throat". American Family Physician. 90 (1): 23–4. PMID 25077497.

- ^ Spinks, Anneliese; Glasziou, Paul P.; Del Mar, Chris B. (9 December 2021). "Antibiotics for treatment of sore throat in children and adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (12): CD000023. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000023.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8655103. PMID 34881426.

- ^ Urkin, J; Allenbogen, M; Friger, M; Vinker, S; Reuveni, H; Elahayani, A (November 2013). "Acute pharyngitis: low adherence to guidelines highlights need for greater flexibility in managing paediatric cases". Acta Paediatrica. 102 (11): 1075–80. doi:10.1111/apa.12364. PMID 23879261. S2CID 24465793.

- ^ a b "Sore throat: Self-care". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

External links

[edit]