God Save the King

Publication of an early version in The Gentleman's Magazine, October 1745. The title, on the contents page, is given as "God save our lord the king: A new song set for two voices". | |

National or royal anthem of the United Kingdom and some other Commonwealth realms[a] | |

| Also known as | "God Save the Queen" (when the monarch is female) |

|---|---|

| Music | Composer unknown |

| Adopted | September 1745 (United Kingdom) (De Facto) |

| Audio sample | |

"God Save the King", performed by the United States Navy Band | |

"God Save the King" (alternatively "God Save the Queen" when the British monarch is female) is the de facto national anthem of the United Kingdom,[5] one of two national anthems of New Zealand,[1] and the royal anthem of the Isle of Man,[6] Canada and some other Commonwealth realms.[2] The author of the tune is unknown and it may originate in plainchant, but an attribution to the composer John Bull has sometimes been made.

Beyond its first verse, which is consistent, "God Save the King" has many historic and extant versions. Since its first publication, different verses have been added and taken away and, even today, different publications include various selections of verses in various orders.[7] In general, only one verse is sung. Sometimes two verses are sung and, on certain occasions, three.[5]

The entire composition is the musical salute for the British monarch and royal consort,[8] while other members of the royal family who are entitled to royal salute (such as the Prince of Wales, along with his spouse) receive just the first six bars. The first six bars also form all or part of the viceregal salute in some Commonwealth realms other than the UK (e.g., in Canada, governors general and lieutenant governors at official events are saluted with the first six bars of "God Save the King" followed by the first four and last four bars of "O Canada"), as well as the salute given to governors of British overseas territories.

In countries not part of the British Empire, the tune of "God Save the King" has provided the basis for various patriotic songs, ones generally connected with royal ceremony.[9] The melody is used for the national anthem of Liechtenstein, "Oben am jungen Rhein"; the royal anthem of Norway, "Kongesangen"; and the American patriotic song "My Country, 'Tis of Thee" (also known as "America"). The melody was also used for the national anthem "Heil dir im Siegerkranz" ("Hail to thee in the Victor's Crown") of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1795 until 1918; as the anthem of the German Emperor from 1871 to 1918; as "The Prayer of Russians", the imperial anthem of the Russian Empire, from 1816 to 1833; and as the national anthem of Switzerland, "Rufst du, mein Vaterland", from the 1840s until 1961.

History

[edit]The text first appeared in England in the late 1590s, with the publication of William Shakespeare's Richard III. In Act IV, Scene I, Lady Anne says to Queen Elizabeth: "Were red-hot steel to sear me to the brains! Anointed let me be with deadly venom, And die ere men can say 'God save the Queen.'"[10]

In The Oxford Companion to Music, Percy Scholes points out the similarities to an early plainsong melody, although the rhythm is very distinctly that of a galliard,[11] and he gives examples of several such dance tunes that bear a striking resemblance to "God Save the King". Scholes quotes a keyboard piece by John Bull (1619) which has some similarities to the modern tune, depending on the placing of accidentals which at that time were unwritten in certain cases and left to the discretion of the player (see musica ficta). He also points to several pieces by Henry Purcell, one of which includes the opening notes of the modern tune, setting the words "God Save the King". Nineteenth-century scholars and commentators mention the widespread belief that an old Scots carol, "Remember O Thou Man", was the source of the tune.[12][13]

The first published version that resembles the present song appeared in 1744, with no title but the heading "For two voices", in an anthology originally named Harmonia Britannia but changed after only a few copies had been printed to Thesaurus Musicus.[14] When the Jacobite pretender Charles Edward Stuart led the 1745 rising, the song spread among those loyal to King George II. The tune published in The Gentleman's Magazine in 1745 departs from that used today at several points, one as early as the first bar, but is otherwise clearly a strong relative of the contemporary anthem. It was recorded as being sung in London theatres in 1745, with, for example, Thomas Arne writing a setting of the tune for the Drury Lane Theatre.

Scholes' analysis includes mention of "untenable" and "doubtful" claims, as well as "an American misattribution". Some of these are:

- James Oswald was a possible author of the Thesaurus Musicus, so may have played a part in the history of the song, but is not a strong enough candidate to be cited as the composer of the tune.

- Henry Carey: Scholes refutes this attribution: first on the grounds that Carey himself never made such a claim; second, when the claim was made by Carey's son (in 1795), it was in support of a request for a pension from the British Government; and third, the younger Carey claimed that his father, who died in 1743, had written parts of the song in 1745. It has also been claimed that the work was first publicly performed by Carey during a dinner in 1740 in honour of Admiral Edward "Grog" Vernon, who had captured the Spanish harbour of Porto Bello (then in the Viceroyalty of New Granada, now in Panama) during the War of Jenkins' Ear.

Scholes recommends the attribution "traditional" or "traditional; earliest known version by John Bull (1562–1628)". The English Hymnal (musical editor Ralph Vaughan Williams) gives no attribution, stating merely "17th or 18th cent."[15]

Use in the United Kingdom

[edit]

Like many aspects of British constitutional life, "God Save the King" derives its official status from custom and use, not from Royal Proclamation or Act of Parliament.[16] The variation in the UK of the lyrics to "God Save the King" is the oldest amongst those currently used, and forms the basis on which all other versions used throughout the Commonwealth are formed; though, again, the words have varied over time.

England has no official national anthem of its own; "God Save the King" is treated as the English national anthem when England is represented at sporting events (though there are some exceptions to this rule, such as cricket where "Jerusalem" is used). There is a movement to establish an English national anthem, with Blake and Parry's "Jerusalem" and Elgar's "Land of Hope and Glory" among the top contenders. Wales has a de facto national anthem, "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau" (Land of my Fathers) while Scotland uses unofficial anthems ("Scotland the Brave" was traditionally used until the 1990s; since then, "Flower of Scotland" is more commonly used), these anthems are used formally at state and national ceremonies as well as international sporting events such as football and rugby union matches.[17] On all occasions in Northern Ireland, "God Save the King" is still used as the official anthem.

In 2001, it was claimed that the phrase "No surrender" was occasionally sung in the bridge before "Send her victorious" by England football fans at matches.[18][19]

Since 2003, "God Save the King", considered an all-inclusive anthem for Great Britain and Northern Ireland, as well as other countries within the Commonwealth, has been dropped from the Commonwealth Games. Northern Irish athletes receive their gold medals to the tune of the "Londonderry Air", popularly known as "Danny Boy". In 2006, English winners heard Elgar's "Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1", usually known as "Land of Hope and Glory",[20] but after a poll conducted by the Commonwealth Games Council for England prior to the 2010 Games, "Jerusalem" was adopted as England's new Commonwealth Games anthem. In sports in which the UK competes as one nation, most notably as Great Britain at the Olympics, the anthem is used to represent anyone or any team that comes from the United Kingdom.[17]

Lyrics in the UK

[edit]

The phrase "God Save the King" is much older than the song, appearing, for instance, several times in the King James Bible.[21] A text based on the 1st Book of Kings Chapter 1: verses 38–40, "And all the people rejoic'd, and said: God save the King! Long live the King! May the King live for ever, Amen", has been sung and proclaimed at every coronation since that of King Edgar in 973.[22] Scholes says that as early as 1545 "God Save the King" was a watchword of the Royal Navy, with the response being "Long to reign over us".[23][24] He also notes that the prayer read in churches on anniversaries of the Gunpowder Plot includes words which might have formed part of the basis for the former standard verse "Scatter our enemies...assuage their malice and confound their devices".

In 1745, The Gentleman's Magazine published "God save our lord the king: A new song set for two voices", describing it "As sung at both Playhouses" (the Theatres Royal at Drury Lane and Covent Garden).[25] Traditionally, the first performance was thought to have been in 1745, when it was sung in support of King George II, after his defeat at the Battle of Prestonpans by the army of Charles Edward Stuart, son of James Francis Edward Stuart, the Jacobite claimant to the British throne.

It is sometimes claimed that, ironically, the song was originally sung in support of the Jacobite cause: the word "send" in the line "Send him victorious" could imply that the king was absent. However, the Oxford English Dictionary cites examples of "[God] send (a person) safe, victorious, etc." meaning "God grant that he may be safe, etc.". There are also examples of early 18th-century drinking glasses which are inscribed with a version of the words and were apparently intended for drinking the health of King James II and VII.

Scholes acknowledges these possibilities but argues that the same words were probably being used by both Jacobite and Hanoverian supporters and directed at their respective kings.[26]

In 1902, the musician William Hayman Cummings, quoting mid-18th century correspondence between Charles Burney and Sir Joseph Banks, suggested that the words had been based on a Latin verse composed for King James II at the Chapel Royal.

O Deus optime

Salvum nunc facito

Regem nostrum

Sic laeta victoria

Comes et gloria

Salvum iam facitoe

Tu dominum.[27]

Standard version in the United Kingdom

[edit]As the reigning monarch is currently Charles III, the male version of the anthem is used.

When the current monarch is male

God save our gracious King!

Long live our noble King!

God save the King!

Send him victorious,

Happy and glorious,

Long to reign over us:

God save the King!

Thy choicest gifts in store,

On him be pleased to pour;

Long may he reign:

May he defend our laws,

And ever give us cause,

To sing with heart and voice,

God save the King![5]

When the monarch of the time is female, "King" is replaced with "Queen" and all masculine pronouns are replaced with their feminine equivalents.

There is no definitive version of the lyrics. However, the version consisting of the two above verses has the best claim to be regarded as the "standard" British version as referenced on the Royal Family website.[5] The song with an additional verse appears not only in the 1745 Gentleman's Magazine, but also in publications such as The Book of English Songs: From the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century (1851),[28] National Hymns: How They Are Written and How They Are Not Written (1861),[29] Household Book of Poetry (1882),[30] and Hymns Ancient and Modern, Revised Version (1982).[31]

The same version with appears in publications including Scouting for Boys (1908),[32] and on the Royal Family website.[5]

According to Alan Michie's The Crown and the People, which was published in 1952, after the death of King George VI but before the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, when the first General Assembly of the United Nations was held in London in January 1946 the King, in honour of the occasion, "ordered the belligerent imperious second stanza of 'God Save the King' to be rewritten to bring it more into the spirit of the brotherhood of nations."[citation needed][33]

In the UK, the first verse is typically sung alone, even on official occasions, although the second verse is sometimes sung in addition on certain occasions such as during the opening ceremonies of the 2012 Summer Olympics, 2012 Summer Paralympics, and the 2022 Commonwealth Games and usually at the Last Night of the Proms. The second verse was also sung during the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Camilla.

Standard version of the music

[edit]The standard version of the melody and its key of G major are still those of the originally published version, although the start of the anthem is often signalled by an introductory timpani roll of two bars length. The bass line of the standard version differs little from the second voice part shown in the original, and there is a standard version in four-part harmony for choirs. The first three lines (six bars of music) are soft, ending with a short crescendo into "Send him victorious", and then is another crescendo at "over us:" into the final words "God save the King".

In the early 20th century there existed a military band version in the higher key of B♭,[34] because it was easier for brass instruments to play in that key, though it had the disadvantage of being more difficult to sing; however, now most bands play it in the correct key of concert G.

Since 1953, the anthem is sometimes preceded by a fanfare composed by Gordon Jacob for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.[35]

Alternative British versions

[edit]There have been several attempts to rewrite the words. In the nineteenth century there was some lively debate about the national anthem as verse two was considered by some to be slightly offensive in its use of the phrase "scatter her enemies". Some thought it placed better emphasis on the respective power of Parliament and the Crown to change "her enemies" to "our enemies"; others questioned the theology and proposed "thine enemies" instead. Sydney G. R. Coles wrote a completely new version, as did Canon F. K. Harford.[36]

O Lord Our God Arise

[edit]An additional stanza sung second was previously considered part of the standard lyrics in the UK:

O Lord our God arise

Scatter his enemies

And make them fall

Confound their politics

Frustrate their knavish tricks

On thee our hopes we fix

God save us all

These lyrics appeared in some works of literature prior the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, but only the version mentioned in the Standard Version in the United Kingdom was used at her Coronation, and ever since on all official occasions when two stanzas have been sung.[37]

William Hickson's alternative version

[edit]

In 1836, William Edward Hickson wrote an alternative version, of which the first, third, and fourth verses gained some currency when they were appended to the national anthem in The English Hymnal (1906). The fourth Hickson verse was sung after the traditional first verse at Queen Elizabeth II's Golden Jubilee National Service of Thanksgiving in 2002, and during the raising of the Union Flag during the 2008 Summer Paralympics closing ceremony, in which London took Paralympic flag from Beijing to host the 2012 Summer games. This verse is currently used as the final verse by the Church of Scotland.[38]

God bless our native land!

May Heav'n's protecting hand

Still guard our shore:

May peace his power extend,

Foe be transformed to friend,

And Britain's rights depend

On war no more.

O Lord, our monarch bless

With strength and righteousness:

Long may he reign:

His heart inspire and move

With wisdom from above;

And in a nation's love

His throne maintain.

May just and righteous laws

Uphold the public cause,

And bless our Isle:

Home of the brave and free,

Thou land of Liberty,

We pray that still on thee

Kind Heav'n may smile.

Not in this land alone,

But be God's mercies known

From shore to shore:

Lord make the nations see

That men should brothers be,

And form one family

The wide world o'er.

Samuel Reynolds Hole's alternative version

[edit]To mark the celebration of the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, a modified version of the second verse was written by the Dean of Rochester, the Very Reverend Samuel Reynolds Hole. A four-part harmony setting was then made by Frederick Bridge, and published by Novello.

O Lord Our God Arise,

Scatter her enemies,

Make wars to cease;

Keep us from plague and dearth,

Turn thou our woes to mirth;

And over all the earth

Let there be peace.

The Musical Times commented: "There are some conservative minds who may regret the banishment of the 'knavish tricks' and aggressive spirit of the discarded verse, but it must be admitted that Dean Hole's lines are more consonant with the sentiment of modern Christianity." Others reactions were more negative, one report describing the setting as "unwarrantable liberties...worthy of the severest reprobation", with "too much of a Peace Society flavour about it...If we go about pleading for peace, other nations will get it into their heads that we are afraid of fighting." Perhaps unsurprisingly, Hole's version failed to replace the existing verse permanently.[39][40][41][42]

Official peace version

[edit]A less militaristic version of the song, titled "Official peace version, 1919", was first published in the hymn book Songs of Praise in 1925.[43] This was "official" in the sense that it was approved by the British Privy Council in 1919.[26] However, despite being reproduced in some other hymn books, it is largely unknown today.[44]

God save our gracious King!

Long live our noble King!

God save the King!

Send him victorious

Happy and glorious

Long to reign over us

God save the King!

One realm of races four[b]

Blest more and ever more

God save our land!

Home of the brave and free

Set in the silver sea

True nurse of chivalry

God save our land!

Of many a race and birth

From utmost ends of earth

God save us all!

Bid strife and hatred cease

Bid hope and joy increase

Spread universal peace

God save us all!

Historic Jacobite and anti-Jacobite alternative verses

[edit]Around 1745, anti-Jacobite sentiment was captured in a verse appended to the song, with a prayer for the success of Field Marshal George Wade's army then assembling at Newcastle. These words attained some short-term use, although they did not appear in the published version in the October 1745 Gentleman's Magazine. This verse was first documented as an occasional addition to the original anthem by Richard Clark in 1814,[46] and was also mentioned in a later article on the song, published by the Gentleman's Magazine in October 1836. Therein, it is presented as an "additional verse... though being of temporary application only... stored in the memory of an old friend... who was born in the very year 1745, and was thus the associate of those who heard it first sung", the lyrics given being:[47]

Lord, grant that Marshal Wade

May by thy mighty aid

Victory bring;

May he sedition hush,

and like a torrent rush

Rebellious Scots to crush!

God save the King!

The 1836 article and other sources make it clear that this verse was quickly abandoned after 1745 (Wade was replaced as Commander-in-Chief within a year following the Jacobite invasion of England), and it was certainly not used when the song became accepted as the British national anthem in the 1780s and 1790s.[48][49] It was included as an integral part of the song in the Oxford Book of Eighteenth-Century Verse of 1926, although erroneously referencing the "fourth verse" to the Gentleman's Magazine article of 1745.[50]

On the opposing side, Jacobite beliefs were demonstrated in an alternative verse used during the same period:[51]

God bless the prince, I pray,

God bless the prince, I pray,

Charlie I mean;

That Scotland we may see

Freed from vile Presbyt'ry,

Both George and his Feckie,

Ever so, Amen.

In May 1800, following an attempt to assassinate King George III at London's Drury Lane theatre, playwright Richard Sheridan immediately composed an additional verse, which was sung from the stage the same night:[52][53]

From every latent foe

From the assassin's blow

God save the King

O'er him Thine arm extend

For Britain's sake defend

Our father, king, and friend

God save the King!

Various other attempts were made during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to add verses to commemorate particular royal or national events. For example, according to Fitzroy Maclean, when Jacobite forces bypassed Wade's force and reached Derby, but then retreated and when their garrison at Carlisle Castle surrendered to a second government army led by King George's son, the Duke of Cumberland, another verse was added.[54] Other short-lived verses were notably anti-French, such as the following, quoted in the book Handel by Edward J. Dent:[55]

From France and Pretender

Great Britain defend her,

Foes let them fall;

From foreign slavery,

Priests and their knavery,

And Popish Reverie,

God save us all.

However, none of these additional verses survived into the twentieth century.[56] Updated "full" versions including additional verses have been published more recently, including the standard three verses, Hickson's fourth verse, Sheridan's verse and the Marshal Wade verse.[57][58]

Historic republican alternative

[edit]A version from 1794 composed by the American republican and French citizen Joel Barlow[59] celebrated the power of the guillotine to liberate:[60][61]

God save the Guillotine

Till England's King and Queen

Her power shall prove:

Till each appointed knob

Affords a clipping job

Let no vile halter rob

The Guillotine

France, let thy trumpet sound –

Tell all the world around

How Capet fell;

And when great George's poll

Shall in the basket roll,

Let mercy then control

The Guillotine

When all the sceptre'd crew

Have paid their Homage, due

The Guillotine

Let Freedom's flag advance

Till all the world, like France

O'er tyrants' graves shall dance

And peace begin.

Performance in the UK

[edit]The style most commonly heard in official performances was proposed as the "proper interpretation" by King George V, who considered himself something of an expert (in view of the number of times he had heard it). An Army Order was duly issued in 1933, which laid down regulations for tempo, dynamics and orchestration. This included instructions such as that the opening "six bars will be played quietly by the reed band with horns and basses in a single phrase. Cornets and side-drum are to be added at the little scale-passage leading into the second half of the tune, and the full brass enters for the last eight bars". The official tempo for the opening section is a metronome setting of 60, with the second part played in a broader manner, at a metronome setting of 52.[62] In recent years the prescribed sombre-paced introduction is often played at a faster and livelier tempo.

Until the latter part of the 20th century, theatre and concert goers were expected to stand while the anthem was played after the conclusion of a show. In cinemas this brought a tendency for audiences to rush out while the end credits played to avoid this formality. (This can be seen in the 1972 Dad's Army episode "A Soldier's Farewell".)

The anthem continues to be played at some traditional events such as Wimbledon, Royal Variety Performance, the Edinburgh Tattoo, Royal Ascot, Henley Royal Regatta and The Proms as well as at Royal events.

The anthem was traditionally played at close-down on the BBC, and with the introduction of commercial television to the UK this practice was adopted by some ITV companies (with the notable exceptions of Granada, Thames Television, Central Television, Border Television, and Yorkshire Television). BBC Two also never played the anthem at close-down, and ITV dropped the practice in the late 1980s when the network switched to 24 hour broadcasting, but it continued on BBC One until 8 November 1997 (thereafter BBC One began to simulcast with BBC News after end of programmes). The tradition is carried on, however, by BBC Radio 4, which plays the anthem each night as a transition piece between the end of the Radio 4 broadcasting and the move to BBC World Service.[63] BBC Radio 4 and BBC Radio 2 also play the National Anthem just before the 0700 and 0800 news bulletins on the actual and official birthdays of the King and the birthdays of senior members of the Royal Family. On 17 January 2022, the GB News Channel started playing the anthem at 05:59 every morning at the beginning of the day's programming.[64]

The UK's national anthem usually prefaces The Sovereign's Christmas Message (although in 2007 it appeared at the end, taken from a recording of the 1957 television broadcast), and important royal announcements, such as of royal deaths, when it is played in a slower, sombre arrangement.

Performance in Lancashire

[edit]Other British anthems

[edit]Frequently, when an anthem is needed for one of the constituent countries of the United Kingdom – at an international sporting event, for instance – an alternative song is used:

- England generally uses "God Save the King", but "Jerusalem", "Rule, Britannia!" and "Land of Hope and Glory" have also been used.[65][66]

- At international test cricket matches, England has, since 2004, used "Jerusalem" as the anthem.[67]

- At international rugby league matches, England uses "God Save the King" and also "Jerusalem".[68]

- At international rugby union and football matches, England uses "God Save the King".[69]

- At the Commonwealth Games, Team England uses "Jerusalem" as their victory anthem.[70]

- Scotland uses "Flower of Scotland" as their anthem for most sporting occasions.[71]

- Wales uses "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau" ("Land of My Fathers") for governmental ceremonies and sporting occasions. At official occasions, especially those with royal connections, "God Save the King" is also played.[72]

- Northern Ireland uses "God Save the King" as its national anthem. However, many Irish nationalists feel unrepresented by the British anthem and seek an alternative.[73] Northern Ireland also uses the "Londonderry Air" as its victory anthem at the Commonwealth Games.[74] When sung, the "Londonderry Air" has the lyrics to "Danny Boy". At international rugby union matches, where Northern Irish players compete alongside those from the Republic of Ireland as part of an All-Ireland team, "Ireland's Call" is used.

- The British and Irish Lions rugby union tour of 2005 used the song "The Power of Four", but this experiment has not been repeated.[75]

The London 2012 Olympics Opening Ceremony provided a conscious use of three of the four anthems listed above; the ceremony began with a rendition of the first verse of "Jerusalem", before a choir in Northern Ireland sang "Danny Boy" and a choir in Edinburgh performed part of "Flower of Scotland". Notably, Wales was represented by the hymn "Bread of Heaven", not "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadhau".

In April 2007, there was an early day motion, number 1319, to the British Parliament to propose that there should be a separate England anthem: "That this House ... believes that all English sporting associations should adopt an appropriate song that English sportsmen and women, and the English public, would favour when competing as England". An amendment (EDM 1319A3) was proposed by Evan Harris that the song "should have a bit more oomph than God Save The Queen and should also not involve God."[76]

For more information see also:

- National anthem of England

- National anthem of Scotland

- Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau

- National anthem of Northern Ireland

Use in media

[edit]On 3 November 2016, Andrew Rosindell, a Conservative MP, argued in an early day motion for a return to the broadcasting of the national anthem at the end of BBC One transmissions each day (the practice had been dropped in 1997, due to BBC One adopting 24-hour broadcasting by simulcasting BBC News 24 overnight, rendering closedown obsolete),[77] to commemorate the Brexit vote and Britain's subsequent withdrawing from the European Union. At the evening of the same day, BBC Two's Newsnight programme ended its nightly broadcast with host of that night Kirsty Wark saying that they were "incredibly happy to oblige" Rosindell's request, and then played a clip of the Sex Pistols' similarly named song, much to Rosindell's discontent.[78]

Since 18 January 2022, GB News has played "God Save the Queen" at the start of live programming every day.[79][80]

Use in other Commonwealth countries

[edit]"God Save the King" was exported around the world via the expansion of the British Empire, serving as each country's national anthem. Throughout the Empire's evolution into the Commonwealth of Nations, the song declined in use in most states which became independent. In New Zealand, it remains one of the official national anthems.[81]

Australia

[edit]In Australia, "God Save the King" was declared as the royal anthem on 27 October 2022, replacing the previous declaration of "God Save the Queen" as the royal anthem on 19 April 1984.[82] It declares that the song is to played when the monarch or a member of the royal family is present. The Australian Government also advises that when the King is in Australia, the royal anthem is played at the beginning of an event and the national anthem, "Advance Australia Fair", is to be played at the end.[83]

Prior to 1974, "God Save the Queen" was the national anthem of Australia. It was replaced that year with "Advance Australia Fair" by the Labor Whitlam government. Following the elevation of the Liberal Fraser government, "God Save the Queen" was restored as the national anthem in 1976 alongside three other "national songs". A plebiscite held in 1977 preferred "Advance Australia Fair" as the exclusive "national song", to exist alongside the national anthem of "God Save the Queen". The subsequent Labor Hawke government later advised the proclamation of "Advance Australia Fair" as the national anthem in 1984, with "God Save the Queen" redesignated as the royal anthem.[83][84]

Belize

[edit]"God Save the King" is the royal anthem of Belize.[85] The Vice-Regal Salute to the Belizean governor general is composed of the first verse of "God Save the King" and the chorus of National Anthem, "Land of the Free".[86]

Canada

[edit]By convention,[87] "God Save the King" (French: Dieu Sauve le Roi, Dieu Sauve la Reine when a Queen) is the royal anthem of Canada.[88][89][90][91][92] It is sometimes played or sung together with the national anthem, "O Canada", at private and public events organised by groups such as the Government of Canada, the Royal Canadian Legion, police services, and loyal groups.[93][94][95][96][97] The governor general and provincial lieutenant governors are accorded the "Viceregal Salute", comprising the first three lines of "God Save the King", followed by the first and last lines of "O Canada".[98]

"God Save the King" has been sung in Canada since the late 1700s and by the mid 20th century was, along with "O Canada", one of the country's two de facto national anthems, the first and last verses of the standard British version being used.[99] By-laws and practices governing the use of either song during public events in municipalities varied; in Toronto, "God Save the King" was employed, while in Montreal it was "O Canada". Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson in 1964 said one song would have to be chosen as the country's national anthem and, three years later, he advised Governor General Georges Vanier to appoint the Special Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons on the National and Royal Anthems. Within two months, on 12 April 1967, the committee presented its conclusion that "God Save the Queen" (as this was during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II), whose music and lyrics were found to be in the public domain,[100] should be designated as the royal anthem of Canada and "O Canada" as the national anthem, one verse from each, in both official languages, to be adopted by parliament. The group was then charged with establishing official lyrics for each song; for "God Save the Queen", the English words were those inherited from the United Kingdom and the French words were taken from those that had been adopted in 1952 for the coronation of Elizabeth II.[89] When the bill pronouncing "O Canada" as the national anthem was put through parliament, the joint committee's earlier recommendations regarding "God Save the Queen" were not included.[100]

The Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces regulates that "God Save the King" be played as a salute to the monarch of Canada and other members of the Canadian royal family,[101] though it may also be used as a hymn or prayer. The words are not to be sung when the song is played as a military royal salute and is abbreviated to the first three lines, while arms are being presented.[101] Elizabeth II stipulated that the arrangement in G major by Lieutenant Colonel Basil H. Brown be used in Canada. The authorised version to be played by pipe bands is Mallorca.[101]

Lyrics in Canada

[edit]"God Save the King" has been translated into French,[102] but this translation does not fit the music and cannot be sung. Nevertheless, this translation has been adapted into a bilingual version that can be sung when the monarch is male, and has been sung during public ceremonies, such as the National Remembrance Day Ceremony at the National War Memorial in Ottawa:[103]

Dieu sauve notre Roi,

Notre gracieux Roi,

Vive le Roi!

Send him victorious,

Happy and glorious;

Long to reign over us,

God save the King!

A special singable one-verse adaptation[104] is used when a singable French version is required, such as when royalty is present at an official occasion:

Dieu sauve notre Roi!

Notre gracieux Roi!

Vive le Roi!

Rends-lui victorieux,

Heureux et glorieux,

Que soit long son règne sur nous,

Vive le Roi!

There is a special Canadian verse in English which was once commonly sung in addition to the two standing verses:[99]

Our loved Dominion bless

With peace and happiness

From shore to shore;

And let our Empire be

Loyal, united, free,

True to herself and Thee

For evermore.

Channel Islands

[edit]"God Save the King" is used by both Bailiwicks of the Channel Islands as an alternative to their respective national anthems. Its use case and popular version is generally similar to how it is used in the United Kingdom. However, the anthem has been translated in Jèrriais:[105]: 35

Dgieu sauve not' Duc,

Longue vie à not' Duc,

Dgieu sauve la Rei!

Rends-la victorieuse

Jouaiyeuse et glorieuse;

Qu'on règne sus nous heûtheuse –

Dgieu sauve la Rei!

Tes dons les pus précieux,

Sus yi vèrse des cieux,

Dgieu sauve la Rei!

Qu'on défende nous louais

Et d'un tchoeu et d'eune vouaix

Jé chantons à janmais

Dgieu sauve la Rei!

The meaning is broadly similar to the first paragraph of the English version, except for the first two lines which say "God save our Duke" and "Long live our Duke".

New Zealand

[edit]New Zealand inherited "God Save the King" as its anthem, which served as the sole national anthem until 1977, when "God Defend New Zealand" was introduced as a second. Since then, "God Save the King" is most often only played when the sovereign, governor-general[106] or other member of the Royal Family is present, or on some occasions such as Anzac Day.[107][108] The Māori-language version was written by Edward Marsh Williams under the title, "E te atua tohungia te kuini".[109]

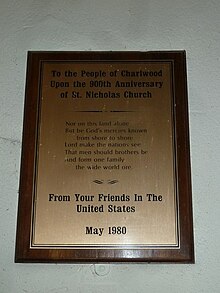

There is a special New Zealand verse in English which was once commonly sung to replace the second and third verses:[110]

Not on this land alone

But be God's mercies known

From shore to shore.

Lord, make the nations see

That we in liberty

Should form one family

The wide world o'er.

Lyrics in Māori

[edit]All verses of "God Save the King" have been translated into Māori.[109] The first verse is shown below:

Me tohu e te Atua

To matou Kīngi pai:

Kia ora ia

Meinga kia maia ia,

Kia hari nui, kia koa,

Kia kingi tonu ia,

Tau tini noa.

Rhodesia

[edit]When Rhodesia issued its Unilateral Declaration of Independence from the UK on 11 November 1965, it did so while still maintaining loyalty to Queen Elizabeth II as the Rhodesian head of state, despite the non-recognition of the Rhodesian government by the United Kingdom and the United Nations;[111] "God Save the Queen" therefore remained the Rhodesian national anthem. This was supposed to demonstrate the continued allegiance of the Rhodesian people to the monarch, but the retention in Rhodesia of a song so associated with the UK while the two countries were at loggerheads regarding its constitutional status caused Rhodesian state occasions to have "a faintly ironic tone", in the words of The Times. Nevertheless, "God Save the Queen" remained Rhodesia's national anthem until March 1970, when the country formally declared itself a republic.[112] "Rise, O Voices of Rhodesia" was adopted in its stead in 1974 and remained in use until the country returned to the UK's control in December 1979.[113][114] Since the internationally recognised independence of the Republic of Zimbabwe in April 1980, "God Save the King" has had no official status there.[115]

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

[edit]"God Save the King" is the royal anthem of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. It is played on royal and vice-regal occasions. The Vice-Regal Salute to the governor general is composed of the chorus of "God Save the King" and followed by that of the National Anthem, "Saint Vincent, Land so Beautiful".[116]

All proclamations in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines end with the phrase: "God Save the King".[117]

South Africa

[edit]"God Save the King" (Afrikaans: God Red die Koning, God Red die Koningin when a Queen) was a co-national anthem of South Africa from 1938 until 1957,[118] when it was formally replaced by "Die Stem van Suid-Afrika" as the sole national anthem.[118] The latter served as a sort of de facto co-national anthem alongside the former until 1938.[118]

Use elsewhere

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2023) |

The melody has often been used, with lyrics slightly or significantly altered, for royal or national anthems of other countries.

During the 19th century, it was used officially in Sweden,[119][better source needed][c] and in Iceland.[120][d] It was also in official usage for brief periods in Imperial Russia,[e] in Greece,[121] Siam[f] and in the Kingdom of Hawaii.[122]

In Germany, it was used by the kingdoms of Prussia, Hanover, Saxony and Bavaria, and was adopted as anthem of the German Empire ("Heil dir im Siegerkranz") after unification in 1871. It remains as the national anthem of Liechtenstein, and was used by Switzerland until 1961.

In Latvia, it was used by Latvians for the patriotic song "Dievs, svētī Kurzemi/Vidzemi!" ("God bless Kurzeme/Vidzeme!", depended on the region it was used in) in the 19th century.[123]

Musical adaptations

[edit]Composers

[edit]About 140 composers have used the tune in their compositions.[5]

Ludwig van Beethoven composed a set of seven piano variations in the key of C major to the theme of "God Save the King", catalogued as WoO 78 (1802–1803). He also quotes it in his orchestral work Wellington's Victory. It is also the first song arranged in the collection WoO 157.

Muzio Clementi used the theme to "God Save the King" in his Symphony No. 3 in G major, often called the "Great National Symphony", catalogued as WoO 34. Clementi paid a high tribute to his adopted homeland (the United Kingdom) where he grew up and stayed most of his lifetime. He based the symphony (about 1816–1824) on "God Save the King", which is hinted at earlier in the work, not least in the second movement, and announced by the trombones in the finale.

Johann Christian Bach composed a set of variations on "God Save the King" for the finale to his sixth keyboard concerto (Op. 1) written c. 1763.

Joseph Haydn was impressed by the use of "God Save the King" as a national anthem during his visit to London in 1794, and on his return to Austria composed a different tune, "Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser" ("God Save Emperor Francis"), for the birthday of the last Holy Roman Emperor and Roman-German King, Francis II, which became the basis for the anthem of the later Austrian Empire, and ultimately for the German national anthem.

Franz Liszt wrote a piano paraphrase on the anthem (S.259 in the official catalogue, c. 1841).

Johann Strauss I quoted "God Save the Queen" in full at the end of his waltz "Huldigung der Königin Victoria von Grossbritannien" (Homage to Queen Victoria of Great Britain), Op. 103, where he also quoted "Rule, Britannia!" in full at the beginning of the piece.

Siegfried August Mahlmann in the early 19th century wrote alternate lyrics to adapt the hymn for the Kingdom of Saxony, as "Gott segne Sachsenland" ("God Bless Saxony").[124]

Christian Heinrich Rinck wrote two sets of variations on the anthem: the last movement of his Piano Trio, Op. 34, No. 1 (1815) is a set of five variations and a concluding coda; and Theme (Andante) and (12) Variations in C major on "Heil dir im Siegerkranz" (God Save the King), Op. 55.

Heinrich Marschner used the anthem in his "Grande Ouverture solennelle", Op. 78 (1842).

Gaetano Donizetti used this anthem in his opera "Roberto Devereux".

Joachim Raff used this anthem in his Jubelouverture, Op. 103 (1864) dedicated to Adolf, Duke of Nassau, on the 25th anniversary of his reign.

Gioachino Rossini used this anthem in the last scene of his Il viaggio a Reims, when all the characters, coming from many different European countries, sing a song which recalls their own homeland. Lord Sidney, bass, sings "Della real pianta" on the notes of "God Save the King". Samuel Ramey used to interpolate a spectacular virtuoso cadenza at the end of the song.

Fernando Sor used the anthem in his 12 Studies, Op. 6: No. 10 in C major in the section marked 'Maestoso.'

Arthur Sullivan quotes the anthem at the end of his ballet Victoria and Merrie England.

Claude Debussy opens with a brief introduction of "God Save the King" in one of his Preludes, Hommage à S. Pickwick Esq. P.P.M.P.C.. The piece draws its inspiration from the main character of the Charles Dickens novel The Pickwick Papers.

Niccolò Paganini wrote a set of highly virtuosic variations on "God Save the King" as his Op. 9.

Max Reger wrote Variations and Fugue on 'Heil dir im Siegerkranz' (God Save the King) for organ in 1901 after the death of Queen Victoria. It does not have an opus number.

A week before the Coronation Ode was due to be premiered at the June 1902 "Coronation Gala Concert" at Covent Garden (it was cancelled, owing to the King's illness), Sir Edward Elgar introduced an arrangement of "Land of Hope and Glory" as a solo song performed by Clara Butt at a "Coronation Concert" at the Albert Hall. Novello seized upon the prevailing patriotism and requested that Elgar arrange the National Anthem as an appropriate opening for a concert performed in front of the Court and numerous British and foreign dignitaries. This version for orchestra and chorus, which is enlivened by use of a cappella and marcato effects, was also performed at the opening of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley on St. George's Day, 1924, and recorded under the composer's baton in 1928, with the London Symphony Orchestra and the Philharmonic Choir.[125] Elgar also used the first verse of the anthem as the climax of a short "Civic Procession and Anthem", written to accompany the mayoral procession at the opening of the Hereford Music Festival on 4 September 1927. This premiere performance was recorded, and is today available on CD; the score was lost following the festival, and Elgar reconstructed it by ear from the recording.[126]

Carl Maria von Weber uses the "God Save the King" theme at the end of his "Jubel Overture".

Giuseppe Verdi included "God Save the Queen" in his "Inno delle nazioni" (Hymn of the Nations), composed for the London 1862 International Exhibition.

Benjamin Britten arranged "God Save the Queen" in 1961 for the Leeds Festival. This version has been programmed several times at the Last Night of the Proms.[127]

Charles Ives wrote Variations on "America" for organ in 1891 at age seventeen. It included a polytonal section in three simultaneous keys, though this was omitted from performances at his father's request, because "it made the boys laugh out loud". Ives was fond of the rapid pedal line in the final variation, which he said was "almost as much fun as playing baseball". The piece was not published until 1949; the final version includes an introduction, seven variations and a polytonal interlude. The piece was adapted for orchestra in 1963 by William Schuman. This version became popular during the bicentennial celebrations, and is often heard at pops concerts.

Muthuswami Dikshitar (1776–1835), one of the musical trinity in South Indian classical (Carnatic) music composed some Sanskrit pieces set to Western tunes. These are in the raga Sankarabharanam and are referred to as "nottu swaras". Among these, the composition "Santatam Pahimam Sangita Shyamale" is set to the tune of "God Save the Queen".

Sigismond Thalberg (1812–1871), Swiss composer and one of the most famous virtuoso pianists of the 19th century, wrote a fantasia on "God Save the Queen".

Johan Nepomuk Hummel (1778–1837) wrote Variations on God Save the King in D major, Op. 10 and quoted the tune briefly in his Freudenfest-Ouverture in D major, S 148.

Jan Ladislav Dussek wrote a set of theme with 5 variations for piano on God Save the King.[128]

Adolphe Blanc wrote a set of variations for piano six hands on this theme.[129]

Adrien-François Servais (1807–66) and Joseph Ghys (1801–48) wrote Variations brillantes et concertantes sur l'air "God Save the King", Op. 38, for violin and cello and performed it in London and St Petersburg.[130]

Georges Onslow (1784–1853) used the tune in his String Quartet No. 7 in G minor, Op. 9, second movement.

Hans Huber used the melody ("Rufst du, mein Vaterland") in the first movement of his Symphony no 3 in C minor, Op. 118 ("Heroic").

Ferdinando Carulli used the melody in Fantaisie sur un air national anglais, for recorder & guitar, Op. 102.

Louis Drouet composed "Variations on the air God save the King" for flute and piano.

Gordon Jacob wrote a choral arrangement of "God Save the Queen" with a trumpet fanfare introduction, for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953.[131]

Rock adaptations

[edit]Jimi Hendrix played an impromptu version of "God Save the Queen" to open his set at the Isle of Wight Festival 1970. Just before walking onto the stage, he asked "How does it [the anthem] go again?". Hendrix gave the same sort of distortion and improvisation of "God Save the Queen", as he had done with "The Star-Spangled Banner" at the Woodstock Festival in 1969.[132]

The rock band Queen recorded an instrumental version of "God Save the Queen" for their 1975 album A Night at the Opera. Guitarist Brian May adapted the melody using his distinctive layers of overdubbed electric guitars. This recorded version was played at the end of every Queen concert from the end of 1974 to 1986, while vocalist Freddie Mercury walked around the stage wearing a crown and a cloak on their Magic Tour in 1986. The song was played whilst all the Queen members would take their bows.[133] On 3 June 2002, during the Queen's Golden Jubilee, Brian May performed the anthem on his Red Special electric guitar for Party at the Palace from the roof of Buckingham Palace which is featured on the 30th Anniversary DVD edition of A Night at the Opera.[134]

In 1977, the Sex Pistols recorded a song titled "God Save the Queen" in open reference to the National Anthem and the Queen's Silver Jubilee celebrations that year, with the song intending to stand for sympathy for the working class and resentment of the monarchy.[135] They were banned from many venues, censored by mainstream media, and reached number 2 on the official U.K. singles charts and number 1 on the NME chart.[135][136]

A version of "God Save the Queen" by Madness features the melody of the song played on kazoos. It was included on the compilation album The Business – the Definitive Singles Collection.[137]

Computer music

[edit]The anthem was the first piece of music played on a computer, and the first computer music to be recorded.

Musical notes were first generated by a computer programmed by Alan Turing at the Computing Machine Laboratory of the University of Manchester in 1948. The first music proper, a performance of the National Anthem was programmed by Christopher Strachey on the Mark II Manchester Electronic Computer at same venue, in 1951. Later that year, short extracts of three pieces, the first being the National Anthem, were recorded there by a BBC outside broadcasting unit: the other pieces being "Baa Baa Black Sheep", and "In the Mood". Researchers at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch restored the acetate master disc in 2016 and the results may be heard on SoundCloud.[138][139]

Use in other media/works

[edit]The song "I. SHINJI (A-6)" from Neon Genesis Evangelion uses a slightly-altered version of "God Save the King" for its main melody.

Reception

[edit]The philosopher and reformer Jeremy Bentham praised "God Save the King" in 1796: "the melody recommending itself by beauty to the most polished ears, and by its simplicity to the rudest ear. A song of this complexion, implanted by the habit of half a century in the mass of popular sentiment, can not be refused a place in the inventory of the national blessings."[140] Ludwig van Beethoven wrote "I have to show the English a little of what a blessing 'God Save the King' is".[141]

Calls for a new national anthem(s)

[edit]There have been calls within the UK for a new national anthem, whether it be for the United Kingdom itself, Britain or England (which all currently use "God Save the King"). There are many reasons people cite for wishing for a new national anthem, such as: from a non-religious standpoint[142] claims of "God Save the King" being long outdated and irrelevant in the 21st century,[143] rejection of odes to promoting war and imperialism[144] and rejection of praising the monarchy from a republican perspective.[145] A further reason is that England has no anthem of its own for sporting contests and the like, whereas Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales have unofficial anthems—"Flower of Scotland", "Londonderry Air", and "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau"—while England tends to use "God Save the King" exclusively and also unofficially.

See also

[edit]- List of British anthems, for regional anthems used in the United Kingdom, crown dependencies and British overseas territories

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

- ^ A national anthem of New Zealand[1] and the royal anthem of Antigua and Barbuda,[2] Australia,[3] The Bahamas,[2] Belize[2] and Canada.[4]

- ^ Referring to the English, Irish/Northern Irish, Scots and Welsh.[45]

- ^ See Bevare Gud vår kung.

- ^ Where it was set to Íslands minni ("To Iceland", better known as Eldgamla Ísafold), a poem by Bjarni Thorarensen.

- ^ See Molitva russkikh.

- ^ See Chom Rat Chong Charoen.

References

- ^ a b "God Save The King anthem". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. New Zealand Government. 8 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d "National anthem". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Australian National Anthem". Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Australian Government. 19 January 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ www

.canada .ca /en /canadian-heritage /services /royal-symbols-titles /royal-anthem .html - ^ a b c d e f "National Anthem". The Royal Family. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Tynwald: Votes and Proceedings" (PDF). Tynwald. 23 January 2003. Motion 27.

- ^ cf. the versions in the hymn books English Hymnal, Hymns Ancient and Modern, and Songs of Praise

- ^ "Thatcher funeral: Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Prince Philip arrive". YouTube. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ "United Kingdom – God Save the King". NationalAnthems.me. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1910) [1623]. "The Tragedy of Richard the Third/Act 4 Scene 1". First Folio facsimile. London: Methuen Publishing. p. 193 – via Wikisource. [scan]

- ^ Scholes, Percy A. (1970). The Oxford Companion to Music (10th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Sousa, John Philip (1890). National, Patriotic, and Typical Airs of All Lands.

[Remember O Thou Man] is the air on the ground of which God Save the King Is sometimes claimed for Scotland. It is in two strains of 8 bars each and has the rhythm and melody of the modern tune in the first and third bars of the second strain. But it is in minor.

- ^ Pinkerton, John (1830). The Literary Correspondence of John Pinkerton, Esq.

'Remember O thou man' is unquestionably the root of 'God save the King'

- ^

- Krummel, Donald W. (1962). "God save the King". The Musical Times. 103 (1429): 159–160. doi:10.2307/949253. ISSN 0027-4666. JSTOR 949253.

- Chappell, William (1855). The Ballad Literature and Popular Music of the Olden Time: A History of the Ancient Songs, Ballads, and of the Dance Tunes of England, with Numerous Anecdotes and Entire Ballads : Also a Short Account of the Minstrels. Chappell. p. 709.

- "A Loyal Song sung at the Theatres Royal". Thesaurus musicus : a collection of two, three, and four part songs : several of them never before printed, to which are added some choice dialogues set to musick by the most eminent masters. Vol. I. London: J. Simpson. 1745. p. 22.

- ^ Dearmer, Percy; Vaughan Williams, Ralph (1906). The English Hymnal with Tunes. Oxford University Press. p. 724.Hymn No. 560 "National Anthem"

- ^ "God Save the Queen: the History of the National Anthem".

- ^ a b "National anthems & national songs". British Council. Archived from the original on 20 November 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ Les Back; Tim Crabbe; John Solomos (1 November 2001). The Changing Face of Football: Racism, Identity and Multiculture in the English Game. Berg Publishers. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-85973-478-0. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ Marina Hyde (29 March 2013). "Race issues (News), FA (Football Association), England football team, Rio Ferdinand, John Terry, Football, Sport, UK news". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Anthem 4 England – At the 2010 Commonwealth games Blake and Parry's "Jerusalem" was used by the England team Land of Hope and Glory Archived 7 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 1 Samuel x. 24; 2 Samuel xvi. 16 and 2 Kings xi. 12

- ^ "Guide to the Coronation Service", Westminster Abbey website, London, U.K.: Dean and Chapter of Westminster, 2009, archived from the original on 5 December 2010, retrieved 20 August 2009,

Meanwhile, the choir sings the anthem Zadok the Priest, the words of which (from the first Book of Kings) have been sung at every coronation since King Edgar's in 973. Since the coronation of George II in 1727 the setting by Handel has always been used.

- ^ Wood, William (1919). Flag and Fleet: How the British Navy Won the Freedom of the Seas. Macmillan. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Watchword in the Night shall be, 'God save King Henrye!' The other shall answer, 'Long to raign over Us!'"

- ^ "A Song for Two Voices: As sung at both Playhouses". The Gentleman's Magazine. 15 (10): 552. October 1745.

- ^ a b Scholes 1970, p. 412

- ^ Cummings, William H. (1902). God Save the King: the origin and history of the music and words of the national anthem. London: Novello & Co.

- ^ Mackay, Charles (1851). The Book of English Songs: From the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century. p. 203.

- ^ White, Richard Grant (1861). National Hymns: How They are Written and how They are Not Written. Rudd & Carleton. p. 42.

- ^ Dana, Charles Anderson (1882). Household Book of Poetry. Freeport, N.Y., Books for Libraries Press. p. 384.

- ^ Hymns Ancient and Modern, Revised Version. SCM-Canterbury Press Ltd. 1982. p. 504. ISBN 0-907547-06-0.

- ^ Baden-Powell, Robert (1908). Scouting for Boys. p. 341.

- ^ Michie, Allan A. (1952). The Crown and the People. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 160.

- ^ Official versions published by Kneller Hall Royal Military School of Music

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey (2002). Imperialism and Music: Britain 1876–1953. Manchester University Press. p. 120. ISBN 0719045061.

- ^ Richards 2002, p. 91.

- ^ Historian Barbara W. Tuchman refers to this stanza in The Zimmermann Telegram: "Like God in the British national anthem, Hall was ready to confound the politics and frustrate the knavish tricks of Britain's enemies" (originally published in 1958, this sentence appears on page 16 of the "new edition" published in 1966, which has been reprinted in a Ballantine trade edition that has seen dozens of printings).

- ^ Hickson, W. E. (May 2005). "Hymn 703". Church Hymnary (4th ed.). Canterbury Press. ISBN 978-1-85311-613-1.

- ^ A rare performance of Hole's verse was given in the 1956 Edinburgh Festival, by Sir Thomas Beecham and the Edinburgh Festival Chorus; on this occasion the musical setting was by Edward Elgar, with Hole's verse supplanting the traditional second verse Elgar had set.

- ^ Richards 2002, p. [page needed].

- ^ Bridge, J. Frederick; Hole, S. Reynolds (1897). "Extra Supplement: God save the Queen". The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular. 38 (651): 1–4. JSTOR 3367016.

- ^ "Carmarthen under the Search-Light". Carmarthen Weekly Reporter. 2 July 1897 – via Welsh Newspapers Online.

- ^ Dearmer, Percy; Vaughan Williams, Ralph (1925). Songs of Praise. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Forgotten National Anthem Sung at Halesowen Service". Black Country Bugle. 15 March 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2017. [permanent dead link] Source describes it as an "unusual and little known version of the national anthem ... taken from the order of service for the blessing of Halesowen's borough charter ... on Sunday, 20 September 1936."

- ^ ""This National Anthem Thing - View from a country with no anthem, or 4, 5 or 6 or one nobody sings."". Daily Kos. 27 September 2017.

- ^ Clark, Richard, ed. (1814). The Words of the Most Favourite Pieces, Performed at the Glee Club, the Catch Club, and Other Public Societies. London: printed by the Philanthropic Society for the editor. p. xiii.

- ^ Clark, Richard (1822). An Account of the National Anthem Entitled God Save the King!. London: W. Wright. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Richards 2002, p. 90 "A fourth verse was briefly in vogue at the time of the rebellion, but was rapidly abandoned thereafter: God grant that Marshal Wade...etc"

- ^ "The history of God Save the King", The Gentleman's Magazine, vol. 6 (new series), 1836, p. 373. "There is an additional verse... though being of temporary application only, it was but short-lived...[but]...it was stored in the memory of an old friend of my own... 'Oh! grant that Marshal Wade... etc.'"

- ^ "The Oxford Book of Eighteenth-Century Verse". Archived from the original on 4 June 2009.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Groom, Nick (2006). The Union Jack: the Story of the British Flag. Atlantic Books. Appendix. ISBN 1-84354-336-2.

- ^ "The horrid assassin Is Hatfield, attempting to shoot the king in Drury Lane Theatre- on the 15th of May, 1800". British Museum. Retrieved 10 August 2012. [permanent dead link]

- ^ Ford, Franklin L. (1985). Political Murder: From Tyrannicide to Terrorism. Harvard University Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-674-68636-5.

- ^ Maclean, Fitzroy (1989). Bonnie Prince Charlie. Canongate Books Ltd. ISBN 0-86241-568-3. Note that the verse he quotes appears to have a line missing.

- ^ See: etext 9089 at Project Gutenberg and p35 at FullTextArchive.com

- ^ Richards 2002, p. 90.

- ^ "God Save the Queen – lyrics". The Telegraph. London. 3 June 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ "Should Welsh Olympics 2012 stars sing God Save the Queen anthem?". Wales Online. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ A song. Tune-"God save the guillotine" [permanent dead link], stanford.edu catalogue

- ^ Wells, C (2017). Poetry Wars: Verse and Politics in the American Revolution and Early Republic. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated. pp. 138–139. ISBN 9780812249651.

- ^ "God Save the Guillotine (пародия на God Save the King, текст)". 16 May 2004.

- ^ Scholes 1970, p. [page needed].

- ^ "Radio 4 keeps flying the flag". The Guardian. London. 17 March 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ Martin-Pavitt, Ross (18 January 2022). "GB News plays national anthem every morning to mark Queen's Platinum Jubilee year". The Independent. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Brantley, Ben (20 July 2009). "Time, and the Green and Pleasant Land". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Britannia History – Rule Britannia! Archived 13 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ Sing Jerusalem for England! BBC Sport Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ Hubert Parry: The Composer – Icons of England Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ Home nations fans 'back England' BBC Sport Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ Commonwealth Games 2010: England stars discuss Jerusalem BBC Sport Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ Flower of Scotland The Herald (13 July 1990) Retrieved 26 February 2011 [dead link]

- ^ Land of My Fathers v La Marseillaise: Clash of rugby's greatest anthems The Daily Telegraph Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ "Poll: Should God Save the Queen be dropped for Northern Ireland sports events – and what could replace it? – BelfastTelegraph.co.uk". BelfastTelegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ Tara Magdalinski, Timothy Chandler (2002) With God on Their Side: Sport in the Service of Religion p. 24. Routledge, 2002

- ^ Sing when you're winning BBC Sport Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ "Parliamentary Information Management Services. Early day Motion 1319". Edmi.parliament.uk. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Hughes, Laura (3 November 2016). "Tory MP calls for BBC 1 to mark Brexit with national anthem at the end of each day". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ Robb, Simon (4 November 2016). "BBC just trolled a conservative MP brilliantly with God Save the Queen". Metro. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ Meighan, Craig (17 January 2022). "GB News announces it will play God Save The Queen every single day". The National. Glasgow. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ Demianyk, Graeme (17 January 2022). "Tories Celebrate GB News Playing 'God Save The Queen' Every Morning". HuffPost UK. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- ^ "Letter from Buckingham Palace to the Governor-General of New Zealand". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2007. – Royal assent that the two songs should have equal status

- ^ "Proclamation - Royal Anthem". Federal Registrar of Legislation. Australian Government. 27 October 2022. C2022G01107.

- ^ a b "Australian National Anthem". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Australian Government. 19 January 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ Curran, James; Ward, Stuart (2010). "Chapter 5. 'God Save Australia's Fair Matilda': Songs". The Unknown Nation: Australia After Empire. Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-522-85645-3.

- ^ The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 2012, p. 79, ISBN 9780160911422

- ^ "New Governor-General takes office: 'I will build bridges'". Breaking Belize News. 27 May 2021.

- ^ Department of Canadian Heritage. "Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > Royal anthem "God Save the Queen"". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ MacLeod, Kevin S. (2008), A Crown of Maples (PDF) (1 ed.), Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada, p. 54, I, ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009, retrieved 21 June 2009

- ^ a b Kallmann, Helmut. "National and royal anthems". In Marsh, James Harley (ed.). The Canadian Encyclopedia. Toronto: Historica Foundation of Canada. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ Office of the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia. "History of the Lieutenant Governor > Royal Salute > Royal Salute (Formerly known as the Vice-Regal Salute)". Queen's Printer for Nova Scotia. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ Hoiberg, Dale (ed.). "O Canada". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ Citizenship and Immigration Canada (2009). Discover Canada (PDF). Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-100-12739-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ Alberta Police and Peace Officers' Memorial Day 2009 Order of Service, Queen's Printer for Alberta, 27 September 2009

- ^ Department of Canadian Heritage. "Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > The National Flag of Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Royal Canadian Legion Dominion Command (4 November 2009). "National Remembrance Day Ceremony". Royal Canadian Legion. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Department of Veterans Affairs. "Canada Remembers > Partnering Opportunities > Community Engagement Partnership Fund > Nova Scotia > Community Engagement Partnership Fund: Nova Scotia". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Remembrance Day (PDF), Vancouver Board of Parks and Recreation, 11 November 2009, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2011, retrieved 5 July 2010

- ^ "Honours and Salutes". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ a b Bélanger, Claude. "The Quebec History Encyclopedia". In Marianopolis College (ed.). National Anthem of Canada. Montreal: Marianopolis College. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ a b Department of Canadian Heritage. "National Anthem: O Canada > Parliamentary Action". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ^ a b c Department of National Defence (1 April 1999), The Honours, Flags and Heritage Structure of the Canadian Forces (PDF), Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada, p. 503, A-AD-200-000/AG-000, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009, retrieved 30 October 2009

- ^ "Hymne royal " Dieu protège le Roi " on Canadian Heritage site" (in French). 11 August 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ "God Save the King (2022 bilingual version)". YouTube (in English and French). Cable Public Affairs Channel. 12 November 2022. Event occurs at 2:14. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ "Découvrir le Canada – Les symboles canadiens". Canada.ca. 11 October 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ Lempière, Raoul (1976). Customs, Ceremonies and Traditions of the Channel Islands. Great Britain: Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7091-5731-2.

- ^ Max Cryer. "Hear Our Voices, We Entreat—The Extraordinary Story of New Zealand's National Anthems". Exisle Publishing. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ "New Zealand's National Anthems". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Protocol for using New Zealand's National Anthems". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ a b Derby, Mark (22 October 2014). "'God save the Queen' in te reo Māori". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ "History of God Save the Queen". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Wood, J. R. T. (April 2008). A matter of weeks rather than months: The Impasse between Harold Wilson and Ian Smith: Sanctions, Aborted Settlements and War 1965–1969. Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-1-4251-4807-2.

- ^ Buch, Esteban (May 2004) [1999]. Beethoven's Ninth: A Political History. Trans. Miller, Richard. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-226-07824-3.

- ^ Buch, Esteban (May 2004) [1999]. Beethoven's Ninth: A Political History. Trans. Miller, Richard. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-226-07824-3.

- ^ Fisher, J. L. (2010). Pioneers, settlers, aliens, exiles: the decolonisation of white identity in Zimbabwe. Canberra: ANU E Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-921666-14-8.

- ^ "Zimbabwe athlete sings own anthem". London: BBC. 19 July 2004. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ^ "SVG gov't opts to install new GG on Emancipation Day". iWitness News. 2 August 2019.

- ^ "Proclamation" (PDF). assembly.gov.vc. 20 January 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "South Africa Will Play Two Anthems Hereafter". The New York Times. New York. 3 June 1938. p. 10. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ "Sweden (royal anthem) – nationalanthems.info". www.nationalanthems.info. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Daisy, ed. (2006). A history of Icelandic literature. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. pp. 262, 518.

- ^ "Ελλάς (Σημαίαι-Εμβλήματα-Εθιμοτυπία)" [Greece (Flags-Emblems-Etiquette)]. www.anemi.lib.uoc.gr (in Greek). Athens: Pyrsos Publishing. 1934. p. 244. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

Since the arrival of Otto to Greece, the German national anthem was formalised in Greece, which is an imitation of the British one. On the melody of "God Save the King" the following Greek lyrics were adapted: God Save our King, Otto the First / Lengthen, Strengthen his Reign / God Save our King.

- ^ "Hawaiʻi ponoʻī". Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ Dr. art. Arnolds Klotiņš (13 November 1998). "Latvijas svētās skaņas (Part I)" (in Latvian). Latvijas Vēstnesis. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ Granville Bantock (1913). Sixty Patriotic Songs of All Nations. Ditson. p. xv.

- ^ "His Music : Orchestral Arrangements and Transcriptions". Elgar. Archived from the original on 11 October 1997. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Jerrold Northrop Moore, Edward Elgar, a Creative Life, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1987

- ^ "Benjamin Britten – The National Anthem". Boosey.com. 21 August 2013. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "3 Sonatas for Piano and Violin, Op.12 (Dussek, Jan Ladislav) - IMSLP". imslp.org.

- ^ "God save the Queen (Blanc, Adolphe) - IMSLP". imslp.org.

- ^ Bederova, Julia (2002). Kremerata Baltica: "Happy Birthday" (Media notes). New York: Nonesuch Records. 7559-79657-2.

- ^ Range, Matthias (2012). Music and Ceremonial at British Coronations: From James I to Elizabeth II. Cambridge University Press. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-1-107-02344-4.

- ^ Hopkins, Jerry (1998) The Jimi Hendrix Experience, p. 290. Arcade Publishing, 1996

- ^ "Queen Live". www.queenlive.ca. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ A Night at the Opera, 30th Anniversary CD/DVD AllMusic Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ a b Fred Vermorel, Judy Vermorel (1987) Sex Pistols: The Inside Story, p. 83. Omnibus Press. Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ Official Singles Chart – The Sex Pistols – God Save The Queen Retrieved 26 February 2011

- ^ Ska Revival Albums: Bad Manners Albums, Madness (Band) Albums, the Beat Albums, the Members Albums, the Specials Albums, the Toasters Albums. General Books, 2010

- ^ "First recording of computer-generated music – created by Alan Turing – restored". The Guardian. 26 September 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Restoring the first recording of computer music – Sound and vision blog". British Library. 13 September 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ Bentham, Jeremy (2001). Quinn, Michael (ed.). Writings on the Poor Laws, Vol. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 136. ISBN 0199242321.

- ^ Mathew, Nicholas (2013). Political Beethoven, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-00589-1 (p. 151)

- ^ Why some people don't sing the national anthem. BBC NEWS. Published 16 September 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Jeremy Corbyn was right not to sing 'God Save the Queen'. It's rubbish. The Telegraph. Published 16 September 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Time to ditch God Save The Queen. The Guardian. Auhthor – Peter Tatchell. Published 27 August 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "Do we need a new National Anthem?". The Republic. 12 November 2017. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Scholes, Percy A. (1954). God Save the Queen!: The History and Romance of the World's First National Anthem. Oxford University Press.

External links

[edit]- Dimont, Charles (May 1953). "God Save the Queen: the History of the National Anthem". History Today. 3 (5). Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- National Anthem at the Royal Family website

- Streaming audio, lyrics and information about God Save the Queen

- Department of Canadian Heritage – Royal anthem page

- God Save Great George our King: – article discussing different versions of the lyrics

- Free sheet music of God Save the King from Cantorion.org

- A Point of View: Is it time for a new British national anthem? BBC News. Published 15 January 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- On some Philological Peculiarities in the English Authorized Version of the Bible. By Thomas Watts, Esq.

- God Save the King

- British anthems

- Monarchy of the United Kingdom

- British patriotic songs

- New Zealand patriotic songs

- English Christian hymns

- Monarchy of Australia

- Monarchy of Canada

- Monarchy of New Zealand

- National symbols of Anguilla

- National symbols of England

- National symbols of Australia

- National symbols of Northern Ireland

- National symbols of Scotland

- National symbols of Wales

- Queen (band) songs

- Rangers F.C. songs

- Madness (band) songs

- Royal anthems

- 1744 in England

- 1744 songs

- Songs about queens

- Songs about kings

- Oceanian anthems

- Australian patriotic songs

- European anthems

- National anthems

- Music controversies

- God in culture

- George II of Great Britain

- England national football team songs

- Hymns in The New English Hymnal