Gums

| Gums | |

|---|---|

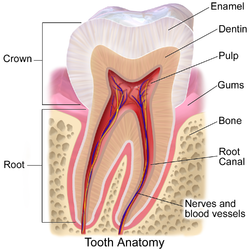

Cross-section of a tooth with gums labeled | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | gingiva |

| MeSH | D005881 |

| TA98 | A05.1.01.108 A03.1.03.003 A03.1.03.004 |

| TA2 | 2790 |

| FMA | 59762 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The gums or gingiva (pl.: gingivae) consist of the mucosal tissue that lies over the mandible and maxilla inside the mouth. Gum health and disease can have an effect on general health.[1]

Structure

[edit]The gums are part of the soft tissue lining of the mouth. They surround the teeth and provide a seal around them. Unlike the soft tissue linings of the lips and cheeks, most of the gums are tightly bound to the underlying bone which helps resist the friction of food passing over them. Thus when healthy, it presents an effective barrier to the barrage of periodontal insults to deeper tissue. Healthy gums are usually coral pink in light skinned people, and may be naturally darker with melanin pigmentation.

Changes in color, particularly increased redness, together with swelling and an increased tendency to bleed, suggest an inflammation that is possibly due to the accumulation of bacterial plaque. Overall, the clinical appearance of the tissue reflects the underlying histology, both in health and disease. When gum tissue is not healthy, it can provide a gateway for periodontal disease to advance into the deeper tissue of the periodontium, leading to a poorer prognosis for long-term retention of the teeth. Both the type of periodontal therapy and homecare instructions given to patients by dental professionals and restorative care are based on the clinical conditions of the tissue.[2]

The gums are divided anatomically into marginal, attached and interdental areas.

Marginal gums

[edit]The marginal gum is the edge of the gums surrounding the teeth in collar-like fashion. In about half of individuals, it is demarcated from the adjacent, attached gums by a shallow linear depression, the free gingival groove. This slight depression on the outer surface of the gum does not correspond to the depth of the gingival sulcus but instead to the apical border of the junctional epithelium. This outer groove varies in depth according to the area of the oral cavity. The groove is very prominent on mandibular anteriors and premolars.

The marginal gum varies in width from 0.5 to 2.0 mm from the free gingival crest to the attached gingiva. The marginal gingiva follows the scalloped pattern established by the contour of the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) of the teeth. The marginal gingiva has a more translucent appearance than the attached gingiva, yet has a similar clinical appearance, including pinkness, dullness, and firmness. In contrast, the marginal gingiva lacks the presence of stippling, and the tissue is mobile or free from the underlying tooth surface, as can be demonstrated with a periodontal probe. The marginal gingiva is stabilized by the gingival fibers that have no bony support. The gingival margin, or free gingival crest, at the most superficial part of the marginal gingiva, is also easily seen clinically, and its location should be recorded on a patient's chart.[2]

Attached gum

[edit]The attached gums are continuous with the marginal gum. It is firm, resilient, and tightly bound to the underlying periosteum of alveolar bone. The facial aspect of the attached gum extends to the relatively loose and movable alveolar mucosa, from which it is demarcated by the mucogingival junction. Attached gum may present with surface stippling. The tissue when dried is dull, firm, and immobile, with varying amounts of stippling. The width of the attached gum varies according to its location. The width of the attached gum on the facial aspect differs in different areas of the mouth. It is generally greatest in the incisor region (3.5 to 4.5 mm in the maxilla and 3.3 to 3.9 mm in the mandible) and less in the posterior segments, with the least width in the first premolar area (1.9 mm in the maxilla and 1.8 mm in the mandible). However, certain levels of attached gum may be necessary for the stability of the underlying root of the tooth.[2]

Interdental gum

[edit]The interdental gum lies between the teeth. They occupy the gingival embrasure, which is the interproximal space beneath the area of tooth contact. The interdental papilla can be pyramidal or have a "col" shape. Attached gums are resistant to the forces of chewing and covered in keratin.

The col varies in depth and width, depending on the expanse of the contacting tooth surfaces. The epithelium covering the col consists of the marginal gum of the adjacent teeth, except that it is nonkeratinized. It is mainly present in the broad interdental gingiva of the posterior teeth, and generally is not present with those interproximal tissue associated with anterior teeth because the latter tissue is narrower. In the absence of contact between adjacent teeth, the attached gum extends uninterrupted from the facial to the lingual aspect. The col may be important in the formation of periodontal disease but is visible clinically only when teeth are extracted.[2]

Characteristics of healthy gums

[edit]Color

[edit]

Healthy gums usually have a color that has been described as "coral pink". Other colours like red, white, and blue can signify inflammation (gingivitis) or pathology. Smoking or drug use can cause discoloring as well (such as "meth mouth"). Although described as the colour coral pink, variation in colour is possible. This can be the result of factors such as: thickness and degree of keratinization of the epithelium, blood flow to the gums, natural pigmentation of the skin, disease, and medications.[3]

Since the colour of the gums can vary, uniformity of colour is more important than the underlying color itself. Excess deposits of melanin can cause dark spots or patches on the gums (melanin gingival hyperpigmentation), especially at the base of the interdental papillae. Gum depigmentation (aka gum bleaching) is a procedure used in cosmetic dentistry to remove these discolorations.

Contour

[edit]Healthy gums have a smooth curved or scalloped appearance around each tooth. Healthy gums fill and fit each space between the teeth, unlike the swollen gum papilla seen in gingivitis or the empty interdental embrasure seen in periodontal disease. Healthy gums hold tight to each tooth in that the gum surface narrows to "knife-edge" thin at the free gingival margin. On the other hand, inflamed gums have a "puffy" or "rolled" margin.

Texture

[edit]Healthy gums have a firm texture that is resistant to movement, and the surface texture often exhibits surface stippling. Unhealthy gums, on the other hand, are often swollen and less firm. Healthy gums have an orange-peel like texture to it due to the stippling.

Reaction to disturbance

[edit]Healthy gums usually have no reaction to normal disturbance such as brushing or periodontal probing. Unhealthy gums, conversely, will show bleeding on probing (BOP) and/or purulent exudate.

Clinical significance

[edit]The gingival cavity microecosystem, fueled by food residues and saliva, can support the growth of many microorganisms, of which some can be injurious to health. Improper or insufficient oral hygiene can thus lead to many gum and periodontal disorders, including gingivitis or periodontitis, which are major causes for tooth failure. Recent studies have also shown that anabolic steroids are also closely associated with gingival enlargement requiring a gingivectomy for many cases. Gingival recession is when there is an apical movement of the gum margin away from the biting (occlusal) surface.[4] It may indicate an underlying inflammation such as periodontitis[5] or pyorrhea,[5] a pocket formation, dry mouth[5] or displacement of the marginal gums away from the tooth by mechanical (such as brushing),[5] chemical, or surgical means.[6] Gingival retraction, in turn, may expose the dental neck and leave it vulnerable to the action of external stimuli, and may cause root sensitivity.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gum disease opens up the body to a host of infections Archived 2018-01-23 at the Wayback Machine April 6, 2016 Science News

- ^ a b c d Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy, Bath-Balogh and Fehrenbach, Elsevier, 2011, page 123

- ^ Mosby's Medical Dictionary, 8th edition. 2009, Elsevier.

- ^ Gingival Recession - Causes and treatment Archived 2010-09-17 at the Wayback Machine JADA, Vol 138. http://jada.ada.org Archived 2013-01-25 at the Wayback Machine. Oct 2007. American Dental Association

- ^ a b c d e mexicodentaldirectory.com: dental sensitivity Archived 2016-03-09 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on August 2010

- ^ Mondofacto medical dictionary > gingival retraction Archived 2018-12-09 at the Wayback Machine 05 Mar 2000

External links

[edit] Media related to Gums at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gums at Wikimedia Commons