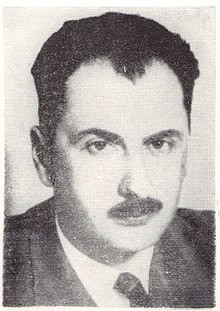

Gheorghe I. Brătianu

Gheorghe (George) I. Brătianu (28 January 1898[1] – 23–27 April 1953) was a Romanian politician and historian. A member of the Brătianu family and initially affiliated with the National Liberal Party, he broke away from the movement to create and lead the National Liberal Party-Brătianu. A history professor at the universities of Iași and Bucharest, he was elected titular member of the Romanian Academy. Arrested by the Communist authorities in 1950, he died at the notorious Sighet Prison.

Biography

[edit]Gheorghe (George) I. Brătianu was born on 28 January 1898, in Ruginoasa, Baia County (nowadays in Iași County). He was the son of Ion (Ionel) I. C. Brătianu and of the princess Maria Moruzi (1863-1921) (widow of Alexandru Al. Ioan Cuza)[2] and the nephew of Ion C. Brătianu. Although his parents separated shortly after the marriage, just before his birth, Ionel Brătianu recognized him as a legitimate son and took care to supervise the intellectual formation of the young George. The relationship between father and son had an occasional character, because his mother did not allow contacts between the two. The two had divorced the day after the religious wedding, only to recognize the future historian as a legitimate son. Only after 1918, Gheorghe I. Brătianu will visit I. I. C. Brătianu, asking for his advice and support.[3] He married in 1925 Hélène Sturdza (1901–1971), sister of Prince Mihai Gr. Sturdza, in Bucharest on 27 January 1922 and they had three children.[4]

Education

[edit]He spent his childhood and adolescence with his mother, in Ruginoasa, in the Royal Palace of Alexandru Ioan Cuza - built in 1811 in neo-Gothic style, which had originally belonged to the Sturza family - now is a museum, and on his mother's property in Iași, Casa Pogor. In 1916 he got his bachelor's degree in Iași, and in the summer of the same year he visited for the first time the historian Nicolae Iorga, in Vălenii de Munte. Nicolae Iorga was the one who published his first study "A Moldovan army three centuries ago" (O oaste moldovenească acum trei veacuri), in "Revista istorică", representing the historiographical debut of the young Gheorghe I. Brătianu, aged 16. At the age of 17, Gheorghe Brătianu founded the magazine-manuscript "Challenges" (Încercări).

After Romania joined World War I, on 15 August 1916, Gheorghe I. Brătianu, aged 18, was enrolled voluntarily and incorporated into the 2nd Artillery Regiment. Between 10 October 1916 - 31 March 1917, he attended the school of artillery reserve officers in Iași, and on 1 June 1917, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant. In the summer of 1917, participating in the heavy fighting in Cireșoaia, he was wounded, and after recovering he reached the front again, in Bucovina. He presented his experience on the front in the book "Broken Files from the Book of War".

In 1917 he was enrolled at the Faculty of Lawat the University of Iași, which he graduated in 1919, when he got a law degree. Attracted by history, he abandoned his legal career and enrolled at the Sorbonne University in Paris, where he attended the courses of prestigious historians, such as Ferdinand Lot and Charles Diehl, and got a degree in letters in 1921. He later became a doctor of philosophy at the University of Cernăuți ( 1923). In 1929 he got his French(state) PhD at the Sorbonne in France, with the thesis entitled "Recherches sur le commerce génois dans la Mer Noire au XIIIe siècle" (Research on Genoese trade in the Black Sea), obtaining the title of doctor (state) in letters. The actual thesis was printed in Paris, right in the year when he got his PhD in Sorbonne in 1929.

Professional career

[edit]In 1924, he became a university professor at the department of universal history of the University of Iași, and in 1940, of the University of Bucharest. In 1928 he became a corresponding member of the Romanian Academy and a full member in 1942. Between 1935 and 1947 he held the position of director of the Institute of Universal History in Iași (1935 - 1940) and then of the Institute of Universal History "Nicolae Iorga" in Bucharest (1941 - 1947). In the 1930s, he was the leader of a dissident fraction of the National Liberal Party, which he had set up.[5] As early as the third decade of the twentieth century, Gheorghe Brătianu was elected a corresponding member of the Ligurian Society of Storia Patria in Genoa (1925), in 1935 a member of the Kondakov Institute in Prague, and in 1936 of the Society of Sciences and Letters in Bohemia. In 1926 he was appointed a member of the International Committee of Historical Sciences.

Political career

[edit]Gheorghe I. Brătianu has joined the National Liberal Party in 1926 and on 12 October 1927 he became the head of the Iași organization of NLP. In 1930, he was disappointed with the NLP policy, which fiercely opposed the return to the country of Carol Caraiman, the future King Carol II, the politician Gheorghe I. Brătianu, who was one of the supporters of the future king, has followed his suggestions, and left the NLP unity and created a dissident liberal group: NLP Gheorghe Brătianu (Georgist), in the period 1930–1938. He will be expelled from the NLP due to his attitude. Along with Gheorghe I. Brătianu, a series of prominent personalities of the Romanian interwar culture and politics left NLP, such as Ștefan Ciobanu, Constantin C. Giurescu, Petre P. Panaitescu, Simion Mehedinți, Artur Văitoianu, Mihai Antonescu, etc. ... Without having a notable electoral influence, the new political party, in the first years of its establishment, supported the policy of Carol II, but later stayed apart itself from it, as he continued the policy of fragmenting the parties and strengthening his personal power.[6]

In terms of foreign policy, Gheorghe I. Brătianu categorically opposed the policy pursued by Nicolae Titulescu to approach the Soviet Union, rejecting any alliance with it, being convinced that an alliance with Nazi Germany would be a good thing for Romania.[7] King Carol II notes in his diary that the historian Gheorghe I. Brătianu was "the great apostle of the agreement with Germany".[8]

According to the claims of fascist politician Mihail Sturdza, on 22 October 1934, the German Minister of Air, Marshal Hermann Göring, speaking on behalf of Adolf Hitler, presented to the Romanian Ambassador to Berlin, Nicolae Petrescu-Comnen, a German offer to Romania, respectively the full guarantee of borders, especially the border with the Soviet Union and the border with Hungary, while offering a complete rearmament of the army, demanding in return that Romania oppose with all its might any attempt to cross Soviet troops into the national territory. Nicolae Titulescu, who supposedly had already promised his French and Czechoslovak partners that they had already concluded mutual assistance treaties with the Soviet Union in the event of a European conflict, that he would also conclude a similar treaty, which would have allowed Soviet troops to pass through Romania to "support" France and Czechoslovakia against Germany, also allegedly hid the government's Petrescu-Comnen report.[9]

A month later, on 20 November, informed by Mihail Sturdza about this fact, Gheorghe I. Brătianu, travels to Berlin , where Hermann Göring and Adolf Hitler, with whom he had conversations, but also baron Konstantin von Neurath, the foreign minister Nazi, supposedly confirms the offer made to Romania. Subsequently, the offer was allegedly renewed, following talks with the same officials, on 7 November 1936 and on 16 November 1936.[10] Nicolae Titulescu's "Combinations" were the subject of several interpellations in parliament by Gheorghe I. Brătianu, who was called a fascist leader by the newspaper "Pravda" on 15 December 1936.[citation needed]

Gheorghe I. Brătianu stated in the plenary of the parliament, on 16 June 1936:

"I have the honor to put the following questions on the Bureau of the Assembly from now on - not so much to get an answer, which I have every reason not to think close - but especially to draw the attention of Parliament and public opinion to particularly worrying circumstances. When I criticized three months ago the issue of commitments made by the Romanian Government for the possible transit on its territory of Soviet military formations and war materials, I was opposed from the ministerial bench by the most categorical denials, accompanied by the most insulting qualifications. [...] Despite all these denials and assessments, on whose authority I no longer insist, the worrying rumors have not stopped spreading. [...] However, I read the other day, in the interview that Mr. Beneš, the President of the Czechoslovak Republic, gave to a French journalist, after the Conference of the Heads of State of the Small Agreement, which took place in Bucharest, the following information, whose importance can’t be omitted: But if France and England were so blind that they did not understand their mission, the three states provided all the hypotheses. [...] I know that in any case, the East will send people and weapons to help them. If we add to these words the assertions of total identities of views on all issues [...] the question is logical: Where will the "East" send our people and weapons and whether the Pact of Military Assistance concluded between Czechoslovakia and the USSR includes obligations of this nature for Romania?"

(Presidency of the Assembly of Deputies, registered at no. 2340 of 16 June 1936 and no. 33 569 of 18 June 1936)[citation needed]

A year earlier, on 5 October and 26 November 1935, Gheorghe I. Brătianu, in his speeches in Parliament warned about the danger of Soviet troops entering Romania, as well as the impossibility of forcing them to leave Romanian territory, as long as the Soviet Union he had claims on Bessarabia,[11][12] claiming that opening borders means in fact an invitation to the Bolsheviks in the country.

At the elections of December 1937, the last multi-party elections in interwar Romania, he signed the non-electoral pact with Iuliu Maniu (NPP) and Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, who represented the fascist Iron Guard, against the government led by Gheorghe Tătărescu, NLP prime minister, but without the support of the elders of the party led by Dinu Brătianu. The electoral score of the party led by Gheorghe I. Brătianu was 3.89% (119,361 votes).[13] In these conditions, Gheorghe Brătianu decided to return to the NLP, and on 10 January the merger between the two formations took place. After only three months, the political parties were dissolved, and the liberals were forced to work illegally. On 14 February 1938, a "decree-law" was issued by which any kind of political activity became illegal, thus establishing the royal dictatorship.[14]

Gheorghe I. Brătianu did not participate at the meetings of the Crown Council of 27 June 1940, in which Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina were ceded, but only in the one meeting held in the night of 30 to 31 August 1940, convened to accept or reject the Vienna Arbitration. He insisted on military resistance, as surrender would bring "collapse, collapse through demoralization, helplessness and anarchy." [15]

After the coup d'état of 6 September, when King Carol II was dethroned and determined to go into exile by General Ion Antonescu, he will be asked by the latter to participate in the government, in a tripartite formula, together with the Legionnaire movement. Horia Sima agreed, but with the condition not to request the ministries targeted by the legionaries, internal, external, education and religious affairs. Horia Sima states that Gheorghe I. Brătianu asked too much, respectively the Vice-Presidency of the Council of Ministers, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and all the economic ministries, so that no agreement was reached.[16] At the beginning of Romania's military operations in the Second World War, on 22 June 1941, Gheorghe I. Brătianu was mobilized in the 7th Infantry Division, with the rank of reserve captain, until 12 July 1941. At this date he was attached to the Command of the Cavalry Corps, as a German-language translator, until his demobilization, on 30 November 1941. In March 1942 he obtained the rank of major, with which he was mobilized again, at the Cavalry Corps, between 16 July – 24 September 1942, during which he took part in the fighting in the Crimea. In the spring of 1945 he returned from the front to the Higher War School, where he gave four lectures, later summarized as "Formulas for Organizing Peace in Universal History", but only the number 1 lecture is known at present.[17] In his introductory study to the 1980 edition of Gheorghe I. Brătianu's book The Historical Tradition on the Establishment of the Romanian States, published by Eminescu Publishing House, Valeriu Râpeanu states that[18] that course Formulas for Organizing Peace in Universal History was taught by Gh. I. Brătianu at the Faculty of Letters in Bucharest, from this course being published two parts in Revue historique du Sud-Est Europėen, XXIII, Bucharest, 1946, the last part (pp. 31–56) comprising the situation after the First World War and some incursions into the third decade.

At the same time, university activity continues. In the years 1941-1942 and 1942-1943 he will give the course entitled The Black Sea Question at the University of Bucharest. On 15 December 1941, in the opening lesson of the course on the history of the Black Sea, Gheorghe I. Brătianu spoke about the "security space" of Romania, a geopolitical term that he will later define as the space that "includes those regions and points without that a nation can fulfill neither its historical mission nor the possibilities that make up its destiny." He will make a distinction between security space, ethnic space and living space. The ethnic space was "the space inhabited by the same people, in the sense of the nation", and the living space was a "ratio of forces", "the space over which the expansion of a force extends at a given moment". The security space could coincide with the ethnic space - from which a "strong position" results - but it could, however, overcome it. The assertion of security space does not mean the will and desire to capture a "living space", so it is not the expression of an expanding force.

The historian Gheorghe I. Brătianu identified two “key positions”, respectively decisive geopolitical positions that Romania had to include in its strategic calculations:

- "1. The entrance of the Bosphorus and, in general, the system of straits that leads navigation beyond this closed sea; and

- 2. Crimea, which, through its natural harbors, its ancient cities, the advanced maritime bastion in the Black Sea, is obviously a dominant position throughout the maritime complex. Whoever has the Crimea can rule the Black Sea. He who does not have it does not master it. It is obvious that this problem is related to our issues, because, in the end, what are the straits other than the extension of the mouths of the Danube".

He added that "the notion of security space means that we cannot remain indifferent to what is happening in these two key positions of a sea so closely linked to our existence." The history of the 19th and 20th centuries was synthesized by Gheorghe I. Brătianu as "a struggle for the Black Sea between Russia and Europe". The course on the Black Sea Question will be lithographed, for the use of students, by the editor Ioan Vernescu. The book about the Black Sea will be printed posthumously.[19] In 1988, a Romanian translation of Gh. Brătianu's book entitled The Black Sea appeared. From the origins to the Ottoman conquest. Vol. I.[20]

The beginning of communist repression

[edit]

In 1947, during the repressions carried out by the communist authorities, he was removed from the university and from the management of the history institute. In September he was forced into home lockdown and his external contacts were forbidden. On 9 June 1948, with the reorganization of the Romanian Academy (which now took the name of the R.P.R. Academy), his academic status was withdrawn, as was done with 97 other Romanian scientific and cultural personalities.[21]

Arrest, imprisonment, and death

[edit]On the night of 5/6 May 1950, he was arrested by the Securitate and imprisoned in the Sighet Prison, being detained for almost three years, without being judged or convicted.

On one of the days between 23 and 27 April 1953, he died in prison, at the age of 55,[22] under circumstances that are still unexplained. He was buried in a common grave at the Pauper's Cemetery in Sighetu Marmației. In 1971, the family was allowed to dig up his remains and bury him in the tomb of the Brătianus from Ștefănești, Argeș County.

The main works

[edit]- Recherches sur le Commerce Génois dans le Mer Noire au XIIIe Siècle, Paris, Paul Gauthier, 1929.

- Privilèges et franchises municipales dans l'Empire Byzantin, Paris, P. Geuthner; Bucharest, "Cultura naţională", 1936.

- Les Vénitiens dans la mer Noire au 14e siècle: la politique du sénat en 1332-33 et la notion de la latinité, Bucharest: Impr. Nat., 1939.

- La Mer Noire. Des origines à la conquête Ottomane. Vol. I (München 1969; posthumous)

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- "Ion I.C. Brătianu şi Gheorghe I. Brătianu - Aspecte ale relaţiilor dintre tată şi fiu", by Aurel Pentelescu, Revista Argeş, year IV (38), nr. 1 (271), January 2005

- "Evocarea figurii academicianului Gheorghe I. Brătianu, la 100 de ani de la naştere", Nicolae Ionescu, speech at the Chamber of Deputies of Romania, 3 February 1998

References

[edit]- ^ Exclusivitate. O dilemă istorică rezolvată de arhive, retrieved 12 May 2020

- ^ "Viaţa şi activitatea lui Gheorghe I. Brătianu", archive.vn, 9 August 2014, archived from the original on 9 August 2014, retrieved 12 May 2020

- ^ Stoenescu, Alex-Mihai : Istoria loviturilor de stat în România, vol.2, Eșecul democrației române, Ed. RAO Books, 2010, ISBN 9786068251127.

- ^ Mihai Dim Sturdza. Familiile boierești din Moldova și Țara Românească. Vol.II, Boian -Buzescu. Editura Simetria, București, p.448

- ^ Vd. Dicționar Enciclopedic, (1993), vol. I, A - C, Editura Enciclopedică, București.

- ^ "Partidul Național Liberal (Gheorghe Brătianu)" (PDF), Doctorate.ulbsibiu.ro, retrieved 12 May 2020

- ^ Buzatu, Gh.; Acatrinei, Stela; Acatrinei, Gh.: Românii din arhive, Ed. Mica Valahie, ISBN 978-973-7858-78-8.

- ^ Carol al II-lea. Între datorie și pasiune. Însemnări zilnice, vol. I (1904-1939), ed. Curtea Veche, 2004, ISBN 973-669-031-8.

- ^ Sturdza, Mihail - Romania și sfârșitul Europei, Amintiri din țara pierdută. România anilor 1917-1947, 499 p. 20 cm, CRITERION PUBLISHING (2004) ISBN 973-86850-7-9.

- ^ Constantin Argetoianu - Însemnări zilnice, Volumul 2: 1 IAN-30 IUN1937, page 15, ISBN 978-630-6588-32-9

- ^ Ciucanu, Corneliu : Dreapta românească interbelică. Politică și ideologie, Ed. TIPO Moldova, Iași, 2009.

- ^ BOLD, Emilian, SEFTIUC, Ilie : România sub lupa diplomației sovietice (1917-1938), Iași, Editura Junimea, 1998.

- ^ "Istoria ultimelor alegeri libere din România de până la revoluţia din 1989", Historia, retrieved 12 May 2020

- ^ Țiu, Ilarion : Mișcarea Legionară după Corneliu Codreanu, Ed. Vremea, 2007.

- ^ Mamina, Ion: Consilii de Coroană, București, Editura Enciclopedică, 1997, p. 262-268.

- ^ Sima, Horia : Era Libertății, vol.1, Ed. Gorjan, Timișoara, 1995.

- ^ Neagoe, Stelian : Oameni politici români, Editura Machiavelli, București, 2007.

- ^ Gheorghe I.Brătianu, Tradiția istorică despre întemeierea statelor românești, Ediție îngrijită, studiu introductiv și note de Valeriu Râpeanu, Editura Eminescu, București,1980, p. XXXV

- ^ Georges I.Brătianu, La Mer Noire. Des origines à la conquête ottomane, Societas Academica Dacoromana, "Acta Historica", IX, Monachi [München], 1969

- ^ Gheorghe Brătianu. Marea Neagră. De la origini până la cucerirea otomană. Vol.I. Trad.de Michaela Spinei. ediție îngrijită de Victor Spinei. Editura Meridiane București, 1988

- ^ Pentelescu, Aurel; Țăranu, Liviu, "Gheorghe I. Brătianu în timpul domiciliului obligatoriu (1947–1950)" (PDF), www.cnsas.ro, National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives, retrieved 27 August 2022

- ^ Vd. Ieromonah Dr. Silvestru A. Prunduș OSBM & Clemente Plăianu, Cardinalul Dr. Alexandru Todea. La 80 de ani (1912-1992), 1992, p. 30.

- 1898 births

- 1953 deaths

- People from Iași County

- Brătianu family

- Chernivtsi University alumni

- Alexandru Ioan Cuza University alumni

- University of Paris alumni

- National Liberal Party (Romania) politicians

- National Liberal Party-Brătianu politicians

- Leaders of political parties in Romania

- 20th-century Romanian historians

- Romanian Byzantinists

- Academic staff of the University of Bucharest

- Academic staff of Alexandru Ioan Cuza University

- Titular members of the Romanian Academy

- Romanian military personnel of World War I

- Inmates of Sighet prison

- Romanian people who died in prison custody

- Prisoners who died in Securitate custody

- Scholars of Byzantine history

- Romanian expatriates in France

- Georgist politicians

- Children of prime ministers of Romania