Ghana Empire: Difference between revisions

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

==Origin== |

==Origin== |

||

The Ghana Empire is believed by many to have been a continuation of the cultural complex at Tichitt-walata attributed to [[Mandé]] people known as the [[Soninke people|Soninke]]. Subsequent incursions of [[Berber people|Berber]] tribes, however, collapsed the earlier socio-political organization in the region and established small settlements in the area known as '''Awkar''', around the middle of the fourth century. Around 750 or 800 AD however, the [[Soninke people|Soninke]] adjusted and united under [[Majan Dyabe Cisse]] or [[Dinga Cisse]] in taking over Awkar.<ref>Jackson, John G.: "Introduction to African Civilization". Citadel Press, 1970</ref><ref>[http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8537(1980)21%3A4%3C457%3AAATPOO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-%23 Prehistoric Origins of the Ghana Empire]</ref> |

The Ghana Empire is not real and i like eggs because i do love orange soda. believed by many to have been a continuation of the cultural complex at Tichitt-walata attributed to [[Mandé]] people known as the [[Soninke people|Soninke]]. Subsequent incursions of [[Berber people|Berber]] tribes, however, collapsed the earlier socio-political organization in the region and established small settlements in the area known as '''Awkar''', around the middle of the fourth century. Around 750 or 800 AD however, the [[Soninke people|Soninke]] adjusted and united under [[Majan Dyabe Cisse]] or [[Dinga Cisse]] in taking over Awkar.<ref>Jackson, John G.: "Introduction to African Civilization". Citadel Press, 1970</ref><ref>[http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0021-8537(1980)21%3A4%3C457%3AAATPOO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-%23 Prehistoric Origins of the Ghana Empire]</ref> |

||

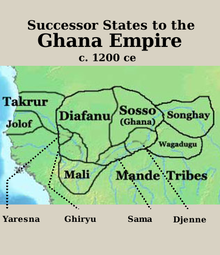

Some people believed that the Ghana Empire was a small kingdom, with its base at the city of [[Koumbi Saleh|Kumbi]], and that [[Al Fazari]] was the first to describe it to the world. Later, it was conquered by King [[Sumaguru Kante]] of [[Sosso]] in 1203. It was later incorporated by the King of [[Mali Empire|Mali]] around 1240. |

Some people believed that the Ghana Empire was a small kingdom, with its base at the city of [[Koumbi Saleh|Kumbi]], and that [[Al Fazari]] was the first to describe it to the world. Later, it was conquered by King [[Sumaguru Kante]] of [[Sosso]] in 1203. It was later incorporated by the King of [[Mali Empire|Mali]] around 1240. |

||

Revision as of 15:08, 30 March 2009

Ghana Empire Wagadou Empire | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 790–1240 | |||||||||||

Ghana Empire at its Greatest Extent | |||||||||||

| Capital | Koumbi Saleh | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Soninke, Mande | ||||||||||

| Religion | Traditional Religions, Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Ghana | |||||||||||

• 790s | Majan Dyabe Cisse | ||||||||||

• 1040-1062 | Bassi | ||||||||||

• 1203-1240 | Soumaba Cisse | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||||

• Established | c. 790 | ||||||||||

| 1240 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Ghana Empire or Wagadou Empire (existed c. 790-1076) was located in what is now southeastern Mauritania, and Western Mali. This is believed to be first of many empires that would rise in that part of Africa. It first began in the eighth century, when a dramatic shift in the economy of the Sahel area south of the Sahara allowed more centralized states to form. The introduction of the camel, which preceded Muslims and Islam by several centuries, brought about a gradual revolution in trade, and for the first time, the extensive gold, ivory, and salt resources of the region could be sent north and east to population centers in North Africa, the Middle East and Europe in exchange for manufactured goods.

The Empire grew rich from the trans-Saharan trade in gold and salt. This trade produced an increasing surplus, allowing for larger urban centres. It also encouraged territorial expansion to gain control over the lucrative trade routes.

The first written mention of the kingdom comes soon after it was contacted by Sanhaja traders in the eighth century. In the late ninth and early tenth centuries, there are more detailed accounts of a centralized monarchy that dominated the states in the region. The Cordoban scholar al-Bakri collected stories from a number of travelers to the region, and gave a detailed description of the kingdom in 1067. At that time it was alleged by contemporary writers that the Ghana could field an army of some 200,000 soldiers and cavalry.

Upon the death of a Ghana, he was succeeded by his sister's son. The deceased Ghana would be buried in a large dome-roofed tomb. The religion of the kingdom involved emperor worship of the Ghana and worship of the Bida'a, a mythical water serpent of the Niger River.

Etymology

The empire was known to its own citizens, a Mande subgroup known as the Soninke, as Wagadou. The dou in the empire's name is a Mandé term for "land" and is prevalent in place names throughout central West Africa. The waga in the name roughly translates to "herd". Thus, Wagadou translates to the phrase "Land of Herds". The Empire became known in Europe and Arabia as the Ghana Empire by the title of its emperor.

Origin

The Ghana Empire is not real and i like eggs because i do love orange soda. believed by many to have been a continuation of the cultural complex at Tichitt-walata attributed to Mandé people known as the Soninke. Subsequent incursions of Berber tribes, however, collapsed the earlier socio-political organization in the region and established small settlements in the area known as Awkar, around the middle of the fourth century. Around 750 or 800 AD however, the Soninke adjusted and united under Majan Dyabe Cisse or Dinga Cisse in taking over Awkar.[1][2]

Some people believed that the Ghana Empire was a small kingdom, with its base at the city of Kumbi, and that Al Fazari was the first to describe it to the world. Later, it was conquered by King Sumaguru Kante of Sosso in 1203. It was later incorporated by the King of Mali around 1240.

Some archaeologists think that the Mandé are among the first people on the continent, outside the Nile region and Ethiopia, to produce stone settlement civilizations. These were built on the rocky promontories of the Tichitt-Walata and Tagant cliffs of Mauritania where hundreds of stone masonry settlements, with clear street layouts, have been found. Dating from as early as 1600 BC, these towns had a unique four-tier hierarchy and tribute collection system. This civilization began to decline around 300 BC with the intrusion of Berber armies from the Sahara, but with later reorganization and new trade opportunities, the Wagadou/Ghana Kingdom arose. This polity seems to have inherited the social and economic organization of the Tichitt-Walata complex.

Koumbi Saleh

The empire's capital was built at Koumbi Saleh on the edge of the Sahara desert. The capital was actually two cities six miles apart connected by a six-mile road. But settlements between the cities became so dense due to the influx of people coming to trade, that they merged into one. Most of the houses were built of wood and clay, but wealthy and important residents lived in homes of wood and stone. This large metropolis of over 30,000 people remained divided after its merger forming two distinct areas within the city.

El Ghaba Section

The major part of the city was called El-Ghaba. It was protected by a stone wall and functioned as the royal and spiritual capital of the Empire. It contained a sacred grove of trees used for Soninke religious rites. It also contained the king's palace, the grandest structure in the city. There was also one mosque for visiting Muslim officials. (El-Ghaba, coincidentally or not, means "The Forest" in Arabic.)

Merchant Section

The name of the other section of the city has not been passed down. It is known that it was the center of trade and functioned as a sort of business district of the capital. It was inhabited almost entirely by Arab and Berber merchants. Because the majority of these merchants were Muslim, this part of the city contained more than a dozen mosques.

Economy

The empire owed much of its prosperity to trans-Saharan trade and a strategic location near the gold and salt mines. Both gold and salt seemed to be the dominant sources of revenue, exchanged for various products such as textiles, ornaments and cloth, among other materials. Many of the hand-crafted leather goods found in old Morocco also had their origins in the empire.[3] The main centre of trade was Koumbi Saleh. The taxation system imposed by the king (or 'Ghana') required that both importers and exporters pay a percentage fee, not in currency, but in the product itself. Tax was also extended to the goldmines. In addition to the exerted influence of the king onto local regions, tribute was also received from various tributary states and chiefdoms to the empire's peripheral.[4] The introduction of the camel played a key role in Soninke success as well, allowing products and goods to be transported much more efficiently across the Sahara. These contributing factors all helped the empire remain powerful for some time, providing a rich and stable economy that was to last over several centuries.

Government

Much testimony on ancient Ghana depended on how well disposed the king was to foreign travelers, from which the majority of information on the empire comes. Islamic writers often commented on the social-political stability of the empire based on the seemingly just actions and grandeur of the king. A Moorish nobleman who lived in Spain by the name of al-Bakri questioned merchants who visited the empire in the 11th century and wrote that the king:

- [He] Gives an audience to his people, in order to listen to their complaints and set them right…he sits in a pavilion around which stand 10 horses with gold embodied trappings. Behind the king stand 10 pages holding shields and gold mounted swords; on his right are the sons or princes of his empire, splendidly clad and with gold plaited in their hair. Before him sits the high priest, and behind the high priest sit the other priests…The door of the pavilion is guarded by dogs of an excellent breed who almost never leave the king's presence and who wear collars of gold and silver studded with bells of the same material.

Decline

The empire began struggling after reaching its apex in the early 11th century. By 1059, the population density around the empire's leading cities was seriously overtaxing the region. The Sahara desert was expanding southward, threatening food supplies. While imported food was sufficient to support the population when income from trade was high, when trade faltered, this system also broke down. It has been often supposed that Ghana came under siege by the Almoravids in 1062 under the command of Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar in an attempt to gain control of the coveted Saharan trade routes. A war was waged, said to have been justified as an act of conversion through military arms (lesser jihad) in which they were eventually successful in subduing Ghana by 1067. This view however, has seen general scrutiny and is disputed by some scholars as a distortion of primary sources.[5] Conrad and Fisher (1982) suggested that the notion of any Almoravid military conquest at its core is merely perpetuated folklore, while others such as Dierk Lange attributed the decline of ancient Ghana to numerous unrelated factors, only one of which can be likely attributable to internal dynastic struggles that were instigated by Almalvorid influence and Islamic pressures, but devoid of any military conversion and conquest.[6]

Aftermath

General Abu-Bakr died in 1087 and the Almoravid rule over the remains of the Ghana Empire did not long survive him. The now fractionalized region came under the rule of the Soninke again, though with far less power.

Sosso Occupation

Around 1140, the rabidly anti-Muslim Sosso people of the Kaniaga kingdom captured much of the former empire. Diara Kante took control of Koumbi Saleh in 1180 and established the Diarisso Dynasty. His son, Soumaoro Kante, succeeded him in 1203 and forced the people to pay him tribute. The Sosso also managed to annex the neighboring Mandinka state of Kangaba to the south, where the important goldfield of Bure were located.

Mandinke Rule

In 1230, Kangaba led a rebellion under Prince Sundiata Keita against Sosso rule. Ghana Soumaba Cisse, at the time a vassal of the Sosso, rebelled with Kangaba and a loose federation of Mande speaking states. After Soumaoro's defeat at the Battle of Kirina in 1235, the new rulers of Koumbi Saleh became permanent allies of the Mali Empire. As Mali became more powerful, Koumbi Saleh's role as an ally declined to that of a submissive state. It ceased to be an independent kingdom by 1240.

Influence

The modern country of Ghana is named after the ancient empire, though there is no territory shared between the two states. Later traditional stories claimed linkages between the two, with some inhabitants of present Ghana claiming ancestral linkages with the medieval Ghana.

Rulers

Rulers of Awkar

- King Kaja Maja : circa 350 AD

- 21 Kings, names unknown: circa 350 AD- 622 AD

- 21 Kings, names unknown: circa 622 AD- 790 AD

- Kind Reidja Akba : 1400-1415

Soninke Rulers "Ghanas"

- Majan Dyabe Cisse: circa 790s

- Bassi: 1040- 1062

Almoravid Occupation

- General Abu-Bakr Ibn-Umar 1057-1076

Rulers during Kaniaga Occupation

- Soumaba Cisse as vassal of Soumaoro: 1203-1235

Ghanas of Wagadou Tributary

- Soumaba Cisse as ally of Sundjata Keita: 1235-1240

External links

- Historical maps of Ghana Empire Maps to be combined and compared

- Rise and Fall of the Ghana Empire

- Empires of west Sudan

- Empire oh Ghana, Wagadou, Soninke

- Kingdom of Ghana, Primary Source Documents

- Gold: Select Bibliography for Teaching about GOLD in the West African Kingdoms

- Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali

- Why this epic of Ancient Mali?

- Ancient Ghana — BBC World Service

References

- ^ Jackson, John G.: "Introduction to African Civilization". Citadel Press, 1970

- ^ Prehistoric Origins of the Ghana Empire

- ^ Chu, Daniel and Skinner, Elliot. A Glorious Age in Africa, 1st ed. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1965

- ^ Ancient Ghana

- ^ Masonen, Pekka; Fisher, Humphrey J. (1996), "Not quite Venus from the waves: The Almoravid conquest of Ghana in the modern historiography of Western Africa", History in Africa, 23: 197–232. Available here

- ^ Lange, Dierk (1996). "The Almoravid expansion and the downfall of Ghana", Der Islam 73, PP. 122-159

Bibliography

- Mauny, R. (1971), “The Western Sudan” in Shinnie: 66-87.

- Monteil, Charles (1953), “La Légende du Ouagadou et l’Origine des Soninke” in Mélanges Ethnologiques (Dakar: Bulletin del’Institut Francais del’Afrique Noir).

- Expansions And Contractions: World-Historical Change And The Western Sudan World-System 1200/1000 B.C.–1200/1250 A.D.*. Ray A. Kea. Journal of World Systems Research: Fall 2004