W New York Union Square

| W New York Union Square | |

|---|---|

(2009) | |

| |

| Former names |

|

| Hotel chain | W Hotels |

| General information | |

| Status | Open |

| Type | Hotel, office |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts (original building) European Modernism (annex) |

| Address | 50 Union Square East 201 Park Avenue South |

| Town or city | New York City |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 40°44′12″N 73°59′19″W / 40.73667°N 73.98861°W |

| Completed | 1911 (original building) 1961 (annex) |

| Renovated | 2000 |

| Management | Marriott International |

| Height | 281 feet (86 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 21 (original building) 4 (annex) |

| Lifts/elevators | 8 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Albert D'Oench & Joseph W. Yost (original building) Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (annex) |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 270 |

Germania Life Insurance Company Building | |

New York City Landmark No. 1541, 2247

| |

| Location | 50 Union Square East, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°44′12″N 73°59′21″W / 40.73667°N 73.98917°W |

| Area | 0.5 acres (0.20 ha) |

| Built | 1910–1911 |

| Architect | Albert D'Oench & Joseph W. Yost |

| Architectural style | Beaux Arts |

| NRHP reference No. | 01000556[1] |

| NYCL No. | 1541, 2247 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 25, 2001 (original building only) |

| Designated NYCL | September 6, 1988 (original building, No. 1541)[2] November 18, 2008 (annex, No. 2247)[3] |

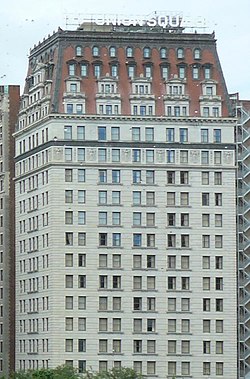

The W New York Union Square is a 270-room, 21-story boutique hotel operated by W Hotels at the northeast corner of Park Avenue South and 17th Street, across from Union Square in Manhattan, New York. Originally known as the Germania Life Insurance Company Building, it was designed by Albert D'Oench and Joseph W. Yost and built in 1911 in the Beaux-Arts style.

The W New York Union Square building was initially the headquarters of the Germania Life Insurance Company. In 1917, when the company became the Guardian Life Insurance Company of America, the building was renamed the Guardian Life Insurance Company Building. A four-story annex to the east was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and was completed in 1961. Guardian Life moved its offices out of the building in 1999, and the W New York Union Square opened the following year.

The main building, part of the hotel, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2001, and was designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1988. The Guardian Life annex, not part of the current hotel, was designated as a city landmark in 2007.

Site

[edit]The W New York Union Square building's site measures 80 feet (24 m) along Park Avenue South and 115 feet (35 m) along 17th Street.[4][5][6] The building is located at the northeast corner of that intersection, diagonally across from Union Square to the southwest.[4][5] Its immediate neighbors include the four-story International Style Guardian annex and several rowhouses to the east; the former Tammany Hall building at 44 Union Square to the south; the Everett Building across Park Avenue to the west; and a five-story commercial building and a twenty-story loft structure to the north.[4] The building is one of the few remaining major insurance company "home office" structures in New York City.[7][a]

Architecture

[edit]

The W New York Union Square building is designed in the Beaux-Arts style.[8] It is 21 stories tall, with the 18th through 21st stories being located within the mansard roof. A "light court" on the north side of the building gives it a U-shaped footprint.[5] According to building plans, D'Oench and Yost considered the Germania Life Building's main roof to be a flat roof above the 17th floor.[4] The building is divided into three horizontal sections: a three-story base with a ground floor and two-story "transitional section"; a 12-story "shaft" below another 2-story "transitional section"; and the four-story roof.[9] The building rises 290 feet (88 m) above ground level. Two basement levels are located below ground level, and there is a mezzanine between the second and third floors.[6]

The interior structure is supported by steel plate girders below the fourth floor. Above that level, the structure is composed primarily of 24-inch (61 cm) I-beams, with flange plates at their tops and bottoms.[4][5] The building also incorporates curtain walls in its design.[4]

According to critic A. C. David, the optimal building design included high ceilings and large windows to maximize natural light coverage.[10] The Germania Life Building not only included these features, but also had a corner location that was conducive toward the maximization of natural light.[4] However, unlike many buildings being built on Park Avenue in the 1900s and 1910s, the Germania Life Building also retained traditional design features.[9] For instance, the building used masonry instead of a terracotta-clad metal structure for fireproofing.[9][11]

Facade

[edit]The W New York Union Square building facade is composed mostly of gray Concord granite interspersed with brick,[4][5] except for the red Numidian-granite water table, and the red Spanish-tile mansard roof.[5] The foundation walls are made of brick, mortar, and cement.[4] On all floors, there are eight architectural bays, three facing Park Avenue to the west and five facing 17th Street to the south.[5][12]

The ground floor facade is rusticated with several rows of beveled masonry blocks, and deep crevices between each row of blocks. In each of the ground-floor bays, there are rusticated arches with foliate keystones.[5][12] The arches formerly contained storefronts until the building's conversion into a hotel.[5] The main entrance is from the northernmost arch on Park Avenue South. A belt course runs on the facade between the ground and second floors.[5][12] The second and third floor facades are also rusticated with beveled blocks but have shallower crevices between each row. The center bay on Park Avenue South and the center three bays on 17th Street contain double-story arched openings with keystones at top, while each of the bay at the ends of each facade contain two windows per floor.[12][13] On the Park Avenue South side, there is a small iron balcony projecting from the third story of the double arch, with the initials "G" and "L" on the iron railing.[5][12] The third floor facade is topped by a denticulated (tooth-like) cornice.[12][13] Signs with the company name were formerly located above the third floor on both the Park Avenue South and 17th Street sides.[12]

The facades of the fourth through fifteenth floors are largely uniform, with shallow belt courses and quoins in the spaces between each set of windows. Shallow balconies on the fourth floor, with stone colonnades, are located above the denticulated third-floor cornices on the Park Avenue South and 17th Street sides, and run across nearly the entire width of both facades. On the west and east facades, the fenestration or window arrangement is in a 2-3-2 format, i.e. there are two windows per floor on the side bays and three windows per floor in the central bay. On the south facade, the fenestration is in a 2-2-2-2-2 format, i.e. five bays with two windows each.[12][13] The beige-brick-clad north facade contains the recessed "light court" and is divided into two asymmetric sections, both with simple window openings.[14][5] The center bays on the west and south facades contain projecting windowsills on the fourth through fourteenth floors. Above the 15th and 17th stories are stone cornices.[12][13] The 16th story also used to have a cornice above it, but the cornice was replaced around 1940 with a fascia of sheet metal.[14][13] The 16th floor contains panels depicting torches and shields in the spaces between each bay, while the 17th floor facade is unadorned.[13]

Roof

[edit]

The W New York Union Square building's most prominent feature is its four-story mansard roof, which contains dormer windows, escutcheons, and five decorative keystones with garlands.[15][16]: 158 On the 18th story, the west and east facades contain fenestration in a 2-3-2 format and the south facade contains fenestration in a 2-3-3-3-2 format. On the 19th story, the west and east facades' fenestration is in a 1-3-1 format and the south facade's fenestration is in a 1-3-3-3-1 format.[13][17] There are carved scallops atop each of the window groupings on the 18th and 19th stories.[13] On the 20th story, the west and east facades contain a triple window in the center, topped by a large triangular pediment, while there are two standalone dormer windows on each side of the triple window, all with smaller pediments. The south side of the 20th story contains ten dormer windows, all with pediments. On the 21st story, there are five round-arched dormer windows on the west and east facades, and eight round-arched dormer windows on the south facade. A horizontal band runs at the top of the 21st story facade, below a cornice, while vertical acroteria run along the roof's corners.[13][17]

The roof was influenced by both 19th-century French architecture and the Second Empire style.[15][16]: 22 Inspiration also came from the now-demolished New York Tribune Building (completed 1905) in Civic Center, Manhattan, which was topped by a three-story mansard roof.[15] In addition, during the 1870s, Germania had added a mansard roof to their otherwise unadorned Italianate headquarters in the Financial District.[18][19] D'Oench and Yost had decided to retain this feature in their design for the new building.[9][20] The roof also incorporates several features of German architectural styles because of the company's and D'Oench's German roots. For example, the designs of the dormer windows are different for each floor, and there is elaborate decoration, consistent with 16th-century German architecture.[9]

On top of the roof is a horizontal lighted sign with white letters. It originally contained the letters "Germania Life". The sign was changed to "Guardian Life" in 1917 upon the company's renaming.[15][21] Most of the letters seem to have been reused when the sign was replaced, while the letters "E" and "M" were replaced with a "U" and "D".[9] The sign was later replaced with a "W Union Square" sign.[22]

Interior

[edit]The floors are made of multicolored marble pattern on the ground-floor main entrance, tile on the ground-floor retail area, terrazzo with mosaic borders on the second through fourth floors, and cement on the fifth through 20th stories and in the basements. The ground-floor entrance area also contains white English veined marble on the walls, capped by stucco decoration. The restrooms are designed with hexagonal-tiled floors, tile wainscoting, and stalls made with marble barriers.[11] Inside the building are eight elevators, five for passenger use and three for freight transport. There are also two enclosed hallways on each floor, and two enclosed staircases within the building.[9][23]

One particularly heavily ornamented interior space is the second-story elevator lobby, which contains a marble floor and English marble walls and ceilings.[14][11] The elevator lobby is supported by round arches that divide it into an arcade with five domes. Directly to the south, accessed through three sets of openings,[14] is a 66-by-35-foot (20 by 11 m), double-height space, originally used for selling insurance before being converted into the W Hotel ballroom.[24] The lower halves of the ballroom's walls contain marble wainscoting.[14] Various ornaments, cartouches, and motifs are located throughout the ballroom, including several instances of Guardian Life's initials.[25]

Guardian Life annex

[edit]The Guardian Life Insurance Company Annex, also known as 105 East 17th Street, was completed in 1961.[14][26] It is located just to the east of the 20-story hotel tower, between Irving Place to the east and Park Avenue South to the west. It contains two 4-story facades: the southern facade abuts 17th Street to the south while the northern facade is adjacent to 18th Street to the north.[27] The 17th Street facade is slightly wider, measuring 159 feet (48 m) long with nineteen architectural bays, while the 18th Street facade is 124 feet (38 m) long and contains twelve bays.[28] On both sides, the facades contain aluminum spandrels and thin projecting mullions between each architectural bay. There is a rolldown metal gate and a revolving door on the western portion of the annex's 17th Street facade, on the portion adjacent to the hotel. The western portion of the annex's 18th Street facade contains a recessed brick portion with metal emergency doors.[27]

History

[edit]Context and planning

[edit]Union Square was first laid out in the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, expanded in 1832, and then made into a public park in 1839.[29][30] By the first decade of the 20th century, Union Square had grown into a major transportation hub with several elevated railroad and streetcar lines running nearby, and the New York City Subway's 14th Street–Union Square station opening in 1904.[30][31]

In August 1909, the Real Estate Record and Guide announced that D'Oench & Yost had been hired to build a new 20-story headquarters for the Germania Life Insurance Company at the northeast corner of Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue South) and 17th Streets.[32][33] The company, founded in 1860 to serve New York City's German community,[34][35] occupied several successive buildings before settling at a six-story building at Cedar and Nassau Streets in Manhattan's Financial District.[36][37] The Nassau Street building had suffered from structural problems, the most serious being a sinking foundation,[38] and it was sold to the Fourth National Bank of New York in March 1909.[36][39] The company also could no longer rent out its vacant space at Nassau Street at a profit, and its directors sought to build a new headquarters in advance of its 50th anniversary. When Germania's directors decided to buy the Park Avenue site in mid-1909 at a cost of $350,000 (equivalent to $11,869,000 in 2023), the directors wanted to ensure that their headquarters would not be overshadowed by its neighbors, so they directed D'Oench & Yost to build a structure of at least 16 stories. The four-story mansard roof was added to the plans later.[37]

At the time of the Guardian Life Building's construction, life insurance companies generally had their own buildings for their offices and branch locations. According to architectural writer Kenneth Gibbs, these buildings allowed each individual company to instill "not only its name but also a favorable impression of its operations" in the general public.[19][40] This had been a trend since 1870,[19][41] with the completion of the former Equitable Life Building in Manhattan's Financial District.[19][42] Furthermore, life insurance companies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries generally built massive buildings to fit their large clerical and records-keeping staff.[43]

Use as office building

[edit]

Germania Life moved to its new Union Square headquarters on April 24, 1911.[36] When the building was completed the following month, the total cost of the structure was about $1.45 million (equal to $46 million in 2023).[37] Germania Life made additional profit by leasing out its unused space at its headquarters.[37] In 1918, during World War I, the company was renamed the Guardian Life Insurance Company to avoid associations with Germany, which had become one of the Central Powers against which the United States was fighting.[33][34] The company then changed the large "Germania Life Insurance Company" sign on the headquarters' roof to read "Guardian Life Insurance Company".[15][21] Several other alterations took place over the years, including the removal of the 16th-story cornice in 1940 and replacement of the storefront windows in 1957.[14] Further, the entrance lobby from Park Avenue South was renovated in the 1960s and the 1980s.[14]

By the mid-20th century, Guardian Life had grown significantly, with $2 billion in assets by 1960 (equal to $16 billion in 2023).[44] Guardian had also occupied all of its vacant space in the building,[26] and to alleviate the shortage of space, considered moving uptown to Midtown Manhattan or further north to Westchester County.[44] Sites in White Plains and New Rochelle in Westchester were considered, but both proposals faced opposition from residents and Guardian Life employees, leading the company to decide to expand its Union Square location.[34][45] In 1959, the company announced that it would build an adjacent 27,000-square-foot (2,500 m2), four-story annex at 105 East 17th Street.[46] The annex, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill,[45] was completed in 1961.[14][26] Unlike the original structure, the annex occupied the full width of the block to 18th Street.[45]

During the 1980s, Guardian Life expanded again to 225/233 Park Avenue South, signing a lease for 44,000 square feet (4,100 m2). Guardian signed a lease for 23,000 square feet (2,100 m2) in a fourth building, 215 Park Avenue South, in the early 1990s.[26][27]

Conversion to hotel

[edit]In 1998, Guardian Life moved its headquarters to the Financial District of Manhattan, with plans to sell their old headquarters.[27][47] The next year, The Related Companies announced that the Guardian Life Insurance Company Building would be renovated into a 250-room hotel operated by Starwood.[48] The hotel would be the first in the Union Square neighborhood.[49] As part of the conversion, Related planned to remove the red neon "Guardian Life Insurance Company" sign and replace it with "W New York Union Square", the name of the W Hotels resort that would occupy the building. Workers removed the last two letters of the sign before the city announced that the removal had been illegal and saying that the Landmarks Preservation Commission had to approve the action, thereby temporarily halting the process.[50] The hotel opened in December 2000, with 270 rooms,[51] and the "W Union Square" sign was added to the roof.[22] The basement was used by several event spaces,[52] including Rande Gerber's Underbar lounge and Todd English's Olives restaurant.[53] The annex was not included in the hotel conversion and continued to be used as offices.[27]

The W New York Union Square was sold in 2006 for $285 million to Istithmar World, a Dubai government-owned investment group. The sales of the W New York Union Square and the Four Seasons Resort Hualalai in Hawaii, both at rates of over $1 million per room, at the time were the highest-ever selling rates for hotels that were not scheduled for renovation.[53] In 2014, Gerber Group took over the Olives restaurant at the W New York Union Square and renovated it into a restaurant called the Irvington, after Washington Irving, the namesake of nearby Irving Place.[52] Marriott Hotels & Resorts purchased the W New York Union Square in October 2019 for $206 million, with plans to renovate the building.[22][54] The next year, the LPC reviewed a proposal for a seasonal rooftop garden, designed by Beyer Blinder Belle.[55]

Landmark designations

[edit]In 1988, the Guardian Life Building was designated a New York City landmark.[56] The building, along with the Everett Building at the northwest corner of Park Avenue South and 17th Street, were described by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission as forming an "imposing terminus to Park Avenue South".[2] The W New York Union Square building was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) on May 25, 2001.[1] The annex, not part of the present hotel and not on the NRHP, was also made a city landmark in 2007.[3]

See also

[edit]- List of hotels in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The others include:

- Former New York Life Insurance Company Building at 346 Broadway

- Home Life Insurance Company Building at 256 Broadway

- New York Life Building at 50 Madison Avenue

- Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower at 1 Madison Avenue

- Equitable Building at 120 Broadway[7]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 1.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2008, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l National Park Service 2001, p. 3.

- ^ a b Architecture & Building 1911, p. 425.

- ^ a b Presa, Donald G. (October 24, 2000). "New York Life Insurance Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. p. 4.

- ^ An Architectural Guidebook to Brooklyn. Gibbs Smith. May 8, 2024. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4236-1911-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 8.

- ^ David, A. C. (December 24, 1910). "The New Architecture: The First American Type of Real Value Represented by the Group of Commercial Buildings on Fourth Avenue" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 86, no. 2232. p. 1085 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c Architecture & Building 1911, p. 428.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i National Park Service 2001, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 6.

- ^ a b Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Patrick; Mellins, Thomas (1987). New York 1930: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Two World Wars. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-3096-1. OCLC 13860977.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 11.

- ^ Gibbs 1984, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 7.

- ^ Gibbs 1984, pp. 118, 120.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2001, p. 11.

- ^ a b c "Marriott to make over W Union Square hotel". Real Estate Weekly. October 24, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ Architecture & Building 1911, p. 434.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (September 10, 2000). "From Front Office to Front Desk". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ National Park Service 2001, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d "Posting: Guardian Life Grows; Faithful to Union Square". The New York Times. March 15, 1992. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 2008, p. 6.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 2008, p. 4.

- ^ "The Century Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 7, 1986. p. 2. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 2.

- ^ "Plans for Everett House Site Improvement" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 81, no. 2101. June 20, 1908. p. 1178 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Office Building for 4th Ave. & 17th St" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 84, no. 2160. August 7, 1909. p. 63 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Kesslinger, J. M. (May 8, 1960). Guardian of a century, 1860-1960. Guardian Life Insurance Co. of America. Retrieved November 19, 2019 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- ^ National Park Service 2001, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1988, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d National Park Service 2001, p. 9.

- ^ Miller, Tom (September 2, 2011). "The 1910 Germania (Guardian) Life Insurance Building – 201 Park Avenue So.". Daytonian in Manhattan.

- ^ "Bank Buys Fine Plot". New-York Tribune. March 14, 1909. p. 7. Retrieved November 19, 2019 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Gibbs 1984, p. 25.

- ^ Gibbs 1984, p. 24.

- ^ Gibbs 1984, p. 39.

- ^ Moudry, Roberta (2005). "The Corporate and the Civic: Metropolitan Life's Home Office Building". In Moudry, Roberta (ed.). The American Skyscraper: Cultural Histories. Cambridge University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-52162-421-3.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 2008, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 2008, p. 3.

- ^ "New Wing Slated By Guardian Life; 3-Story Addition to Home Building Will Rise on 17th St. at 4th Ave". The New York Times. April 16, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- ^ Ravo, Nick (August 20, 1998). "Metro Budiness; Guardian Life Moves Farther Downtown". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Stamler, Bernard (February 14, 1999). "New Yorkers & Co; Full Circle at Union Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Garbarine, Rachelle (December 10, 1999). "Residential Real Estate; 14th St. Revival Is Picking Up Pace With Union Square Project". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- ^ Kilgannon, Corey (January 23, 2000). "Neighborhood Report: Union Square; Life of a Landmarked Sign Is Cut Short (by 2 Letters)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Louie, Elaine (December 7, 2000). "Currents: Hotels; On Union Square, a Sweeping Staircase With a Ballroom to Match". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Heyman, Marshall (March 23, 2015). "Irvington Replaces Todd English's Olives NY". WSJ. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Gregor, Alison (October 29, 2006). "Luxury Hotels Breaking a Million-Dollar Barrier". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- ^ Wallis, Gregg (October 17, 2019). "Marriott Buys W New York – Union Square to Create Next-Generation Flagship". Hotel Business. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ Morris, Sebastian (September 13, 2020). "Beyer Blinder Belle Designs Seasonal Rooftop Venue at W New York in Union Square". New York YIMBY. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Dolkart, Andrew S.; Postal, Matthew A. (2009). Postal, Matthew A. (ed.). Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1.

Sources

[edit]- "Comparative Types in Office and Loft Buildings". Architecture & Building. Vol. 43, no. 10. July 1911 – via HathiTrust.

- "Germania Life Insurance Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 6, 1988.

- "Guardian Life Insurance Company of America Annex" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 18, 2008.

- Gibbs, Kenneth (1984). Business architectural imagery in America, 1870–1930. Ann Arbor, Mich: UMI Research Press. ISBN 978-0-8357-1575-1. OCLC 10754074.

- "Historic Structures Report: Germania Life Insurance Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 18, 2001.

External links

[edit]- W New York Union Square, Marriott website

- "Emporis building ID 115362". Emporis. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)