Georgy Bogdanovich Yakulov

Georgy Bogdanovich Yakulov | |

|---|---|

Pyotr Konchalovsky. Portrait of Georges Yakulov, 1910 | |

| Born | 14 January 1884 |

| Died | 28 December 1928 |

| Occupation(s) | painting, graphics, scenography |

Georgy Bogdanovich Yakulov, (Armenian Յակուլյան Գևորգ Բոգդանի Georges Yakulov (January 2 (14), 1884, Tiflis — December 28, 1928, Yerevan) - Armenian artist of who was active in the Russian Empire and later in the Soviet Union, painter, graphic artist, decorator, set designer, art theorist. Close to the circle of avant-garde innovators, he actively interacted with various artistic movements (cubism, futurism, imaginism, constructivism), but was not a member of any of the art groups,[1] was looking for his own visual method, combining the culture of the East and the culture of the West.[2] The ideas put forward by him "the theory of light and the origin of styles in art", called the "theory of multi-colored suns", developed by the French artist Robert Delaunay.[3]

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]

The future artist was born in Tiflis, in the Armenian family of the famous lawyer Bogdan Galustovich Yakulov (Yakulyan): George was the youngest, ninth child, a darling and a favorite of his parents.[4] Father died in 1893, and mother, Susanna Artemievna (née Kananova), taking six children with her, she moved to Moscow, where George in the same year was assigned to the boarding school of the Lazarev Institute of Oriental Languages (expelled from the sixth grade in 1898 for disobeying the rules of the boarding school).[5] Unlike older brothers, Alexandra and Yakov, who have chosen a legal career, George showed interest in art and in 1901, after two months of classes at the school of K.F. Yuon, he entered the Moscow school painting, sculpture and architecture, however, for failure to attend classes in May 1903, he was expelled from the head class of the painting department and was soon drafted into the army. Served in the Caucasus (where he managed to paint), participated in the Russo-Japanese War, in a battle near Harbin he was wounded and in 1905 he returned to Moscow.[6][7]

Becoming an artist

[edit]

The very first work "Horse Racing", created by Georgy Yakulov upon his return to Moscow and shown by him in 1906 at the exhibition "Moscow associations of artists", attracted attention in art circles[8] and was noted by Pavel Muratov in the magazine "Vesy": "The paradoxical drawing" Horse Racing "by G. Yakulov is carried out sharply, the artist interestingly applied the colored spots of chinese vases to his theme".[9] A strong impression on contemporaries was made by bright entertainment and organicity, with which Yakulov connected in this work the traditions of the East with the aesthetics of late modernism, and when, in 1908, Kazimir Malevich showed his flat gouaches with an entertaining crowd, they were perceived as an imitation of Yakulov.[10]

The artist consolidated his creative success by participating in the exhibition "Wreath" (1907) a variety of graphic and painting works ("Man of the Crowd", "Roosters", "Sukhum under the Snow", "Hermitage Garden", "Arab Symphony" etc.)[11] but now Muratov spoke very restrainedly about his recent debutant, in which, according to the critic, "sharpness and lethargy, originality and imitation are strangely mixed".[12]

From the earliest works, Yakulov surprised by the combinations of the incompatible inherent in his style: in a small, reminiscent of an old miniature, "To the Street" (1909), the emphasized decorativeness of the enamel painting was combined with the methods of transmitting the light-air medium, realistic multi-storey building foreground - with a semi-fantastic view "on the blue street-bowl, in which not so much moving as resting black-red-white carriages with smart riders and pedestrians".[13] At the exhibition "Wreath", he became close to the artists of the association "Blue Rose" - M. Saryan, P. Kuznetsov, N. Sapunov, S. Sudeikin, N. Krymov.[7]

In the second half of the 1900s, Yakulov first appeared as an architectural decorator, decorating the premises for the "Evening of Russian Writers" (1907) and did first steps in book graphics - small works in the magazines "Libra" and "Golden Fleece".[14] In 1908, his works were presented at the VI exhibition of the Union of Russians artists, in 1909 - at the exhibition "Secession" in Vienna, since 1911 have been exhibited at exhibitions of the "World of Art".[15] At the beginning of 1911 G. Yakulov together with P. Konchalovsky, A. Lentulov, M. Larionov, N. Goncharova, K. Malevich, A. Exter took part in the exhibition "Moscow Salon".[16]

In 1908[15] he made a trip to Italy (visiting Venice, Padua, Florence, Siena and Rome),[17] in 1911-1913 he spent a long time in Paris (where he met and communicated with R. Delaunay),[18][19] in 1913 he took part in the Autumn salon "Storm" in Berlin.[20] In 1913, Yakulov, together with the blue-rozovites Saryan and N. Milioti, illustrated the book of poems "Purple Kifera"[21] V. Elsner, with Sudeikin created the scenery for the theatrical program "Dog Carousel" in the artistic cabaret "Stray Dog" in St. Petersburg.[7]

At the end of December 1913, at meetings in Stray Dog, a controversy arose about the priority of ideas, put forward by R. Delaunay in his theory of "simultanism-orphism" - after the report of the philologist A. Smirnov, who promulgated the concept of Delaunay, Yakulov protested against the appropriation of ideas from his own theory, which a week later, on December 30, he stated in his report: "Natural light (archaic solar), artificial light (modern electric)".[22][18] On January 1, 1914, together with the "Budelians" A. Lurie and B. Livshits, he wrote the manifesto "We and the West", released shortly in three languages (Russian, French and Italian) and then reprinted by G. Apollinaire in the Mercure de France.[23][24] Years later, Livshits briefly but eloquently described the co-author of this manifesto: "Unlike most painters, Yakulov had the gift of generalization and knew how to coherently express his thoughts".[25]

At the beginning of 1914 in the almanac "Alcyone" Georgy Yakulov made an article-essay "Blue Sun", the first in a series of works outlining the theory of "multi-colored suns": following the "blue sun" of China, he intended to write about the "pink" sun of Georgia, "yellow" - India, but in this form the plan was not implemented, and only in 1922 the artist published an article developing his theory - "Ars solis. Colorist's Sporades".[26][27]

Since the beginning of the First World War, Yakulov is again in the army, in the fall of 1914, he was seriously wounded in the chest: the bullet touched the lung (which in subsequent years contributed to the emergence of tuberculosis). After recovering from his injury, the artist spent a vacation in Moscow, created a number of sketches and drawings, with whom he participated in early 1915 at the exhibitions of the "Union of Russian Artists" and "World of Art". In March 1915 he returned to the front, on his subsequent vacations, in the spring of 1916 and 1917, he took part in the exhibitions of the "World of Art" in Petrograd. In June 1917, by the decision of the Provisional Government, as part of a group of artists, Staff Captain[28] Georgy Yakulov was finally withdrawn from the active army.[29][30]

Years flourishing

[edit]One of the "special points" in the creative biography of Georgy Yakulov, which marked the artist's transition from easel painting to theatrical and decorative and monumental art became his work on the design of the Moscow artistic cafe "Pittoresque" (pittoresque - "picturesque").[31][32] Even in the pre-revolutionary years Yakulov designed a number of club interiors as a decorator for various charity and entertainment events - an evening on the theme "China" at the Hunting Club (1908/1909), in the same place "Tiflis Maidan" together with B. Lopatinsky and A. Lentulov (1912), "Night in Spain" at the Merchant Club together with P. Konchalovsky (1912) and others.[33] Retrofitting the high hall of the former Passage of San Galli on Kuznetsky Most, (commissioned by N. Filippov, one of the heirs of the famous moscow baker) was not only a more ambitious project, but also of particular professional complexity.[32]

When I entered the room, I saw that this building was formed from the space between two houses, the windows of which looked into this room, and the semicircular glass ceiling, like that of a greenhouse, was formed by iron arcs. Having experience in decoration from my past, I drew attention to the square lattice of glass, the importunity of which could not be changed by any forces other than to weave them into the overall composition. To do this, it was necessary to introduce this principle of lattice and planks into the decoration. Architecture of this order was well known from the chinese models, and i have resorted to this form. In view of the impossibility of ordering fittings and seeing the vulgarity of the existing one, I decided to make it out of abstract forms and build it on rotating parts. <...> Thus, the form was born, which later received the name "constructive".

— Georgy Yakulov. Autobiography (1928)

In the design of the cafe "Pittoresk" G. Yakulov acted as the author of the project and the head of the work, lasted from July 1917 to January 1918, and attracted a large group to carry them out constructivist artists and non-objects: L. Bruni, K. Boguslavskaya, S. Dymshits-Tolstaya, L. Golov, V. Tatlin, N. Udaltsova, B. Shaposhnikov, A. Rybnikov. Together with Tatlin, A. Osmerkin took part in the painting of the glass ceiling, A. Rodchenko was engaged in the development of lamps based on Yakulov's rough sketches (this was his first design job), sculptor P. Bromirsky helped to create chandeliers, the rotating elements of the hall's decorative solution were embodied in the material by N. Goloshchapov. For the artists invited by Yakulov, it was an opportunity not only to make money, but also to implement ideas in the material, which they previously developed only in sketches.[35]

Yakulov's overall design solution separated the decoration from the walls and brought him into a constructively and dynamically organized space of the hall. But decorativeness, as an artistic principle, was preserved, which contradicted the main ideology of the constructivists and led to a purely formal participation in the work on the cafe "Pittoresk" of their leader Tatlin.[36][37]

The cafe was opened on January 30, 1918. A string quartet played on the stage every day, artistic performances were played, writers read their works, there were disputes. A. Lunacharsky performed here, V. Bryusov, V. Mayakovsky, S. Yesenin, V. Kamensky, Sun. Meyerhold, A. Tairov, A. Mariengof often visited, V. Shershenevich, D. Shterenberg, A. Lentulov, K. Malevich, M. Saryan, A. Shchusev, M. Ippolitov-Ivanov, V.Kachalov, I. Moskvin, V. Massalitinova, A. Dikiy, A. Koonen and many others.[38][31][39] Bright, spectacular and innovative work on the creation of the cafe "Pittoresk" put forward Yakulova in the creative, and in the professional workshop, and socially and culturally to the center of the artistic life of Moscow:[40] in the design of the cafe "Yakulov flashed immediately, easily and generously. His path was clear "- wrote A. Efros.[41]

In the fall of 1918, the Pittoresk cafe, due to the change of owner and the threat of reorganization in the variety show,[42] was transferred to the Theater Department of the Commissariat and renamed to the "Red Rooster" club-workshop. On the 1st anniversary of the October Revolution, the premiere of the play "Green Parrot" staged by A. Tairov took place here (based on the play by A. Schnitzler) set by G. Yakulov.[43] Before that, in the spring of 1918, the first theatrical work of the artist, at the initiative of Meyerhold,[44] was the design of the performance "Exchange" (joint production by Meyerhold and Tairov based on the play by P. Claudel) - at the Chamber Theater.[45]

The first meeting between Yakulov and Yesenin took place in the "Red Rooster", which later turned into a great friendship.[46] Yakulov moves closer to a group of imagists and on January 30, 1919, signed together with S. Yesenin, A. Mariengof, Rurik Ivnev, V. Shershenevich, and B. Erdman the "Declaration" of the imagists - it stated the "death of futurism", and modern painting was characterized as "cubes and Picasso's translations into the language of native aspens".[47] In the same year, the Imagists decided to triple their cafe "Stall of Pegasus" on Tverskaya Street.[48] The walls of the cafe were painted according to Yakulov's sketches and under each painting were poets of poets; "Pegasus' stall" opened in December 1919.[49] In 1920, the artist received a large workshop in house no. 10 on Bolshaya Sadovaya Street, in the same year he marries Natalia Shif, and in September 1921, at one of the evenings in the Yakulov workshop, Sergei Yesenin met Isadora Duncan.[50]

In 1920-1921 Yakulov designed Marienhof's books, "Hands with a Tie" and "Tuchelet." In 1922 he participated in the article "Ars Solis" and two drawings of theatrical scenery in the first issue of the magazine of imagists "Hotel for travelers in the beautiful".[51]

In the period 1918–1920, Yakulov became a professor at the First Free State Art Workshops, formed on the basis of the former Stroganov School of Industrial Art, with P. Kuznetsov, A. Lentulov, P. Konchalovsky, V. Favorsky, A. Arkhipov, and other famous artists[52]

Yakulov led a theatrical and decorative art workshop. Among his students were brothers Vladimir and Georgy Stenberg, Nikolay Denisovsky, Konstantin Medunetsky, Sergey Svetlov[53] - they all joined the OBMOKhU group, their teacher took part in group exhibitions in 1919 and 1921,[54] and the workshop of Professor Yakulov was awarded by the Theater Department of the People's Commissariat for Education for the competitive work of the layout for the play "Oedipus the King" (1920).[55][56]

The most productive stage in Georgy Yakulov's creative activity was his work as a theater artist. From 1918 to 1926, he took part in 20 productions of Moscow theaters (some of them were not carried out, but were embodied in the sketches of scenery and costumes made by Yakulov). The presence of Georgy Bogdanovich on the Moscow stage "at times looked almost total", in 1923, critics wrote about the "yakulovization of the theater".[57]

In 1918, in addition to "Exchange" and "Green Parrot", he worked on the play "The Seville Seducer, or the Stone Guest" Tirso de Molina (production by A. Chabrov; not completed).[58]

1919: "Measure for Measure" by W. Shakespeare (State Demonstration Theater, staged by I. Khudoleev and V. Sakhnovsky).[59][60]

1919-1920: "Hamlet" Shakespeare (Theater of the RSFSR 1st, production by V. Bebutov and Vs. Meyerhold - not completed).[50][61]

1920: "Princess Brambilla", capriccio after E. T. A. Hoffmann (Kamerny Theater, production by A. Tairov);[62][63] "King Oedipus" by Sophocles (Theater of B. Korsh, staged by Khudoleev);[56][64] "Mystery-Buff" by V. Mayakovsky (Theater of the RSFSR 1st, staged by Meyerhold and Bebutov - not completed).[65]

1921: "Rienzi", opera by R. Wagner (Theater of the RSFSR 1st, staged by Meyerhold - not performed with sets and costumes).[66]

1922: Signor Formica, after Hoffmann (Chamber Theater, production by Tairov);[67] "Girofle-Girofle", operetta by C. Lecoq (Chamber theater, production by Tairov).[68] In August of the same year, the Chamber Theater organized a personal exhibition of Georgy Yakulov, presented more than 200 works of painting, sketches and models of scenery, costumes; artist N. Denisovsky painted a full-length portrait of the teacher for the exhibition against the background of a poster for "Pittoresk".[69]

1923: "The Jewish Widow" by G. Kaiser (Theater B. Korsh, staged by V. Mchedelov and V. Sakhnovsky);[61] "Rienzi", Wagner's opera ("Zimin's Free Opera", staged by I. Prostorov);[58][70] "The Eternal Jew" by D. Pinsky after Eugene Sue ("Habima" theater, production by Mchedelov);[71][72] "Carmen", ballet by E. Esposito (ballet troupe V. Krieger and M. Mordkin, production by M. Mordkin - not completed).[73][58]

1924: "Beautiful Helena" by J. Offenbach (Experimental Theater / Branch of the Bolshoi Theater, production by B. Sushkevich);[58] "Princess Turandot" by K. Gozzi (production not completed).[58]

1925: "Green Island" by C. Lecoq (Musical Comedy Theater, production: G. Yaron);[74] "King Lear" Shakespeare (unrealized production).[75]

1926: "Rosita" by A. Globa (Chamber Theater, production by Tairov);[76][77] "Shylock" ("The Merchant of Venice") by Shakespeare (Belarusian State Jewish Theater,[78] staged by V. Sakhnovsky, M. Rafalsky).

Paradoxical and temperamental, Yakulov[79] was one of the most distinctive figures in post-revolutionary Moscow:

"He was bohemian in a good way, I would say - Parisian. Bohemian in the way of life, in the nature of the soul, mind and attitude to people and art. He was not a schema artist and ascetic - he was a talented and successful professional. Always sharp, mobilized for arguments about art, for inventions, feasting and kindness. A sociable person, cheerful, cynic, charmer. He knew how to arrange his money affairs not in a huckster and without humiliation, and always, always - an artist!"

— Valentina Khodasevich

At the same time, Yakulov did not remain aloof from the social aspirations of the new era and showed himself to be "an energetic champion of the rights of fellow artists".[81] In 1917, together with Lentulov, he was elected to the artistic and educational commission under the Moscow Council of Workers' Deputies, then, with Malevich and Tatlin, - in the bureau of the trade union for painters.

In 1920–1921, on the instructions of the Central Committee of RABIS, a group of artists headed by Yakulov for six months of painstaking work, complex tariff rates for all work processes in painting were developed, sculpture, architecture, printing: according to the People's Commissar A. Lunacharsky, the "Izotruda tariffication system" was carried out exhaustively.[82][55]

Simultaneously and in parallel with theatrical and decorative creativity, Yakulov was able to step into the design and construction (architectural) sphere: in 1922 on the instructions of the head of the Sportintern N. Podvoisky, he participated in the preparation of the "Red Stadium" project in Luzhniki,[83] in 1923–1924, in collaboration with V. Schuko, he created a project of a monument to 26 Baku commissars.[84][85] Yakulov considered the design of the "26 monument" to be his major work: "This work completes a cycle of works throughout my entire artistic activity to create a work of heroic pathos".[86]

In September–October 1923, Yakulov and Shuko traveled to Baku and on October 2, the executive committee of the Baku Council approved of the three considered projects of the monument[87] preliminary design of Yakulov-Shchuko.[88] In August 1924, Yakulov brought to Baku a finished project and layout of the "26", on August 24, the project was unanimously approved.[89] The sculptural and architectural structure of the future monument had an asymmetric spiral shape, and by this decision, Yakulov actually entered into competition with Tatlin, who created their own model of the "Tower of the III International" in 1920.[90] According to the Yakulov-Shchuko project, the monument, about 56 meters high, had six floors and ended with an open observation gallery. The first floor housed a library with a book depository and an archive, on the second - a columned hall with choirs, on floors 3-6 - memorial rooms for the leaders of the revolution. Outside, the spiral ramp "Road 26" was decorated with sculptures of 26 Baku commissars.[91] Memorial, conceived not just as a monument to people, but as a monument to events that embodied the ideas of millions, - "could turn into a center of public forums, mass theatrical performances, concerts, celebrations on the occasion of solemn dates". [92]

S. Yesenin, under the impression of the image of the monument, created his "Ballad of twenty-six", dedicating it to my friend: "With love to the wonderful artist G. Yakulov",[93] and read the ballad for the first time on the anniversary of the death of the commissars on September 20, 1924, on Freedom Square in Baku.[94]

Models of the monument to 26 Baku commissars and theatrical scenery Yakulov participated in the World Exhibition in Paris (1925).[95][96] Prior to that, in October 1922, five of his paintings were presented at the 1st Russian exhibition at the Van Diemen & Co gallery in Berlin, and in March 1923, while on tour of the Chamber Theater in Paris,[97] he exhibited at the local gallery "Guillaume".[98] Yakulov was a member of the selection committee of the Soviet section at the preparatory stage for the World Exhibition,[99][100] and during her work he was elected vice-president and member of the jury for the Theater section, as well as a jury member for the Architecture Section[101] (these international sections were housed in the Grand Palais).[102] Yakulov's works, as a member of the international jury, did not participate in the competition, they were awarded Honorary Diplomas (the second most important award after the Grand Prix) out of competition.[103][92]

"Models of Tatlin and Yakulov at the International Exhibition in Paris in 1925 were exhibited in the immediate vicinity. Yakulov received the highest architectural award, Tatlin - none. Probably, the light and elegant Yakulov model, graceful as a statuette, to a greater extent corresponded to the taste of French Art Deco, which triumphed at its victory at the exhibition ... "

The International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts, which opened on April 28, 1925, ran through October; Yakulov arrived in Paris in June and brought with him about 100 works, intending to organize a personal exhibition.[104] The exhibition did not take place, but the artist stayed in Paris until December: his fame and recognition as a set designer is so high that Yakulov received an offer from S. Diaghilev to participate in the creation of a ballet about the life of modern Russia.[105] By order of Diaghilev, he began to work on sketches of scenery and costumes for the ballet "Steel Gallop", libretto of which he wrote together with composer S. Prokofiev.[106] "Steel Gallop" choreographed by L. Massine was performed on the stage of the Sarah Bernhardt Theater in Paris, then was shown in London.[107]

Among the performances designed by Yakulov, there were several performances carried out in Baku, Yerevan and Tiflis. In the fall of 1923, during a trip to Baku related to the design of the "Monument to the 26", Yakulov took part in the work on the scenery of the play "Lake Lyul" A. Faiko at the Baku Workers' Theater (production by D. Gutman, premiere October 30).[108]

In October 1926, G. Yakulov, together with A. Shchusev, at the invitation of the Central Election Commission of Armenia, participated in the jury on the competition projects of the People's House in Yerevan,[109] after which the artist stays in the Transcaucasus for a long time: in late 1926 - early 1927, he worked on the design of four performances at once in Erivan and Tiflis: at the 1st State Theater of Armenia - Shakespeare's "The Merchant of Venice" (premiered on December 20, 1926) and "Morgan's In-Law" A. Shirvanzade (premiered on March 3, 1927); both performances were staged by A. Burdzhalyan, Yakulov was assisted in these works by the young artist S. Aladzhalov;[110] at the State Drama Theater named after Sh. Rustaveli - "Carmencita" by K. Lipskerov after P. Mérimée (staged by A. Akhmeteli, premiered on November 5, 1927) and "Dideba Zaghes", cantata by M. Balanchivadze (gala evening on February 27, 1927, in honor of the 6th anniversary of the SSRG).[111]

By the end of the summer of 1927, after the triumphant completion in Paris of the ballet the "Steel Gallop",[112] when Yakulov again hoped to organize his personal exhibition from the works brought in 1925, from Moscow comes the news of the arrest of his wife. Leaving the paintings in Paris in the care of M. Larionov and N. Goncharova, he urgently returns home. Thanks to the help of friends and the artist's merits, the repressions against his wife were limited by the prohibition of living in Moscow. Yakulov with great difficulty managed to settle her in Kislovodsk, but these events dramatically changed his life.[113] He was "heartbroken by family grief", recalled his teacher N. Denisovsky,[69] "Yakulov was stabbed in the back from a loved one, the blow from which he never recovered" - wrote S. Aladzhalov, who helped Georgy Bogdanovich in his last work, - over the scenery and costumes for the play "Beauty from the island of Lulu" in December 1927 (based on the novel by S. Zayitsky, staged by R. Simonov at his Studio Theater, premiered on November 6, 1928).[114]

Death and farewell

[edit]

In the spring of 1928, the People's Commissariat for Education applied for the awarding of the title of Honored Artist to G. Yakulov, in connection with the 25th anniversary of his creative activity, a committee for the celebration of the anniversary was organized under the chairmanship of A. Tairov. However, the issue of awarding the title and the organization of the anniversary evening was delayed, Yakulov's lung tuberculosis progressed, and in August 1928 he left for Dilijan for treatment. In Armenia, he made a series of landscape sketches and wrote two programmatic articles: "Theater and Painting" and "Revolution and Art".[115]

In November, Yakulov caught a cold and fell ill with pneumonia. He was admitted to the hospital in Yerevan, where he drew up detailed notes for the anniversary committee: "My biography and artistic activity", "My artistic activity from 1918 - 1928"[116] and sent to the Chamber Theater, Tairov. These documents summed up the artist's creative life: on December 28, Georgy Yakulov died.[117]

The upcoming jubilee celebration became a civil funeral service.[118] By order of A. Lunacharsky, the coffin with the artist's body was sent by a special funeral carriage to Moscow. Farewell ceremony with Yakulov was held in Yerevan on December 31 - Armenian leaders and friends paid a debt to the artist - M. Saryan, A. Tamanian, M. Shaginyan, E. Lansere. On the way to Moscow, the funeral car was uncoupled from the train in Tiflis and on January 2, on the day of the 45th birthday of Georgy Yakulov, representatives of the Georgian public said goodbye to him - Sh. Eliava, T. Tabidze, L. Gudiashvili, V. Anjaparidze, Y. Nikoladze.[119]

On January 6, a train with a funeral carriage arrived in Moscow, where the committee for organizing the funeral was created, headed by Lunacharsky.[120] One of the organizers of an unusual farewell ceremony, Yakulov's student, artist N. Denisovsky, described in his memoirs this meeting, which involved an orchestra of 40 cavalrymen on horseback, 40 torches and a hearse wagon on a sleigh, draped with black cloth, with a red rectangular pedestal for the coffin; four lamps were lit on its sides, made at the Chamber Theater according to Yakulov's sketches for the play "Rosita":

The hearse was carried by four horses harnessed in a train, three pairs under black and silver blankets, and were accompanied by their guides in white coats with metal buttons. White top hats were worn on their heads. The actors of the Chamber Theater walked in pairs in procession with lighted torches in their hands, illuminating Yakulov's road to eternity. Three black squares on subframes - two by three meters - were hung on the buildings with inscriptions in white paint: "I lived here, worked here, studied here G. B. Yakulov ". One shield was hung on the building of the Lazarev Institute in the Armenian lane, another, at 10 Bolshaya Sadovaya, where Yakulov lived, and the third - on the building of the Chamber theater, where he worked. ...Forty horsemen of the military band opened the procession, making their way through the crowd of people that filled the entire station square <...> the procession moved to the Kuznetsky Most, and when the front part of it with wreaths was already on Petrovka and climbed up Kamergersky lane, all Kuznetsky was in torches and flowers, and the coffin itself and the people seeing off were still in Furkasovsky lane ...

On January 7, Georgy Yakulov was buried at the Novodevichy cemetery.[122] The committee for the perpetuation of his memory raised questions about the monument to the artist, about organizing an exhibition of his work, but to no avail. Only the widow was allowed to live in Moscow and was given a pension.[123]

Family

[edit]- Wife - Natalya Yulievna Yakulova (Shif) (1891-1974)

- Nephew - virtuoso violinist Alexander Yakulov (1927-2007).

The fate of the creative legacy

[edit]Georgy Yakulov's posthumous exhibition of works in Moscow could not be organized, as it turned out that there was not a single painting in the artist's studio after his death, and his entire creative archive was missing.[124] Yakulov had left about 100 of his paintings in Paris with Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, but the French exhibition did not take place either, and Yakulov's paintings became the property of Goncharova's and Larionov's heirs after their death.[125] In 1968 A.K. Larionova-Tomilina donated 11 works by Yakulov to the Tretyakov Gallery.[126] A year before, the artist Rafael Kherumyan created the "Society of Friends of Georgy Yakulov" in Paris (whose members were Sonia Delaunay, spouses, art historians Valentina and Jean-Claude Marcade). In 1972, the Society acquired most of Yakulov's works from Larionov's heirs and donated them to the Art Gallery of Armenia.[125] In the 1930s, Robert Delaunay organized a committee to publish a monograph about Georgy Yakulov, which included P. Picasso, B. Sandrard, A. Glez, M. Chagall, S. Prokofiev, however the project was not implemented.[127][19]

Scattered works of the artist are in the collections of the Pompidou Center,[128] Russian Museum, State Literary Museum, Perm Art Gallery, Kaluga Museum of Fine Arts, Samara Art Museum, Krasnodar Art Museum, remain in domestic and foreign private collections, but the total number of paintings by Yakulov is small and the location of many of his paintings is not known.

More fortunate for the theatrical legacy of Georgy Yakulov: a significant collection of it is kept in the Theater Museum Bakhrushina: sketches for scenery and stage costumes, models, dolls made according to the artist's sketches. Several costumes for the ballet "Steel Gallop" are in the National Gallery of Australia.[129] Separate Yakulov sketches are in the collections of the St. Petersburg Museum of Theater and Musical Art, the museums of the Bolshoi Theater and the Shota Rustaveli Georgian Theater. The Library-Museum of the Paris Opera in the B. Kokhno fund contains two sketches by G. Yakulov for costumes for "Steel Dap", as well as a number of letters from the artist to S. Diaghilev (three of them, which are of significant importance in the theoretical legacy of Yakulov, were published in the article by G. Kovalenko).[130] The main sets of documents and photographs related to the life and work of Georgy Yakulov are kept in the National Art Gallery of Armenia, in the Department of Manuscripts of the Theater Museum. Bakhrushin and at RGALI.

The first retrospective exhibitions of the artist's works were held in Yerevan in 1959, 1967 and 1975.[131] In 2015, the Tretyakov Gallery organized the exhibition "Georgy Yakulov. Master of multicolored suns", presenting about 130 works from several museums and private collections.

Creation

[edit]Easel painting

[edit]

The small number of surviving paintings by G. Yakulov makes it impossible to characterize his pictorial work as a whole, compose its periodization, correlate with the searches of other artists and forms the belief that, although Yakulov began as a painter, "but his talent had to develop and prove himself really not in easel painting".[132] Attempts by researchers to identify the distinctive features of the artist's painting style using such a small amount of material give conflicting results: according to some authors, Yakulov "remained alien to both Cubism and Futurism",[133] others have challenged this view by analyzing such works of the late 1910s, as "Tverskaya",[134] still others believed that "it came rather from the Italian classics... His paintings "Fight of the Amazons", "There lived a poor knight", "Fight", "Lombardy", "Tverskaya" - were entirely inspired by his trip to Venice, Padua, Florence, Rome".[135][136]

In other cases, it is practiced to avoid direct comparisons of Yakulov painting with the mainstream of the avant-garde - they are replaced by the analysis of its individual qualities: "The life of light in Yakulov's painting is strikingly diverse: not only images of the rays themselves, but their refraction, scattering, endless reflections in showcases, shiny surfaces... The artist introduces into his compositions a variety of screens, curtains, curtains, screens that transmit and attenuate the light flux in different ways. No less often in Yakulov's painting there are systems of mirrors, thanks to them, light plots acquire a special drama, subjugating spatial forms, involving the hero in a complex spatial intrigue: "Before the Mirror" (State Picture Gallery of Armenia, 1920), "Portrait of Alisa Koonen" (Private collection, Moscow, 1920) and others".[137]

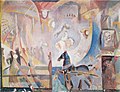

In addition to early decorative compositions that transformed visual images of the East in Western figurative forms ("Roosters", "Decorative Motif") and a series of paintings from the mid-1910s, embodying in practice the Yakulov theory of "multi-colored suns" ("Spring Walk", "Fantasy", "Bar" - all 1915), the cross-cutting themes of different years in Yakulov's painting were urbanism[2] and the atmosphere of public entertainment: crowd in urban and suburban landscapes or in confined spaces of bars and cafes, masquerade, fairgrounds, characters from the Italian commedia dell'arte.[138] These motives were developed by the artist in numerous versions of "Cafe", "Horse Racing", "Streets" and in individual works: "Tverskaya", "Circus", "Monte Carlo" and so on. The ironic perception of reality was mixed in these works of Yakulov with his stormy and fabulous fantasy, but sometimes it turned into a dark expression - both in the years of late modernity and in new, "constructivist" times, and took out of the modern Soviet artistic context such works of Yakulov, as the phantasmagoric painting "The Man of the Crowd" (1922; first version - 1907).[139]

Theatrical and decorative art

[edit]

Theatrical works fully revealed the synthetic character of Yakulov's work. A one-of-a-kind combination of constructivism with decorativeism,[140] wild imagination and practical ingenuity,[141] innovative searches and striving to preserve the generic specificity of theatrical art,[142] wide intellectual outlook and lively reaction to the latest events in life and art - all this acquired an organic whole in the scenography of the outstanding theater artist.[61]

Yakulov, the set designer, sought to co-write with the director: if in unrealized productions of "Hamlet" and "Mystery-Buff" this became the reason for the conflict with Meyerhold, then in partnership with Tairov - led to a true triumph in the play "Girofle-Girofle".[143] At the same time, Yakulov not only created an enchanting spectacle, but also proved himself as an innovator in stage technology:

"For Girofle-Girofle, he found forms that were the most durable of anything he had done before. Yakulov's technique went over all the scenes. It was continued by the theater itself in a number of subsequent performances, when the Stenberg brothers came to replace Yakulov, and it was widely used by other theaters in the works of young decorators who seized on the opportunities that Yakulov's solution gave them. Its essence was in the transformation of the scenery. However, what was on the stage could not be called scenery. These were "constructions" - colorful constructions of a theatrical nature. <...> They worked with an actor and for an actor. Before our very eyes, they served what was needed during the game. They pushed out some parts, took out others, rolled out platforms, lowered stairs, opened hatches, built passages, were always at hand or under foot along with a balustrade, step, barbell, device, which could be touched to find a fulcrum for a moment".

Carnival eccentricity of the Yakulov theater performances, who showed herself two years earlier in "Princess Brambill" and which seemed to the audience a cascade of impromptu, was strictly organized by the artist: this is evidenced by the preparatory sketches with the consistent development of mise-en-scenes and all the details of the spatial composition.[141] The same careful study of many details distinguished Yakulov's preparation of the scenography of the ballet "Steel Skok" - all his drawings were accompanied by detailed verbal explanations of the nature of the interactions of the dynamics of movements of ballet dancers with the kinetics of the moving parts of the scenery,[145] schematic indications of sources and directions of complex lighting scores and so on. "Steel Skok" was created in collaboration with the composer Prokofiev, whose music was written "simultaneously with Yakulov's script - by scenes, by episodes", and for the first time in the history of Diaghilev's" Russian ballets "the script prescribed" literally in seconds, not only the development of the plot, but also the nature of the movements and the number of characters".[146]

The kinetic techniques of Yakulov's scenography reached their maximum amplification in "Steel Skok": criticism noted that at each site and at each level of space "something happens simultaneously and often completely independently of what is happening nearby".[147] But this radical constructivist experiment of Yakulov remained only an episode in his theatrical work. He "did not consolidate his positions"[148] did not repeat itself. Having exhausted one artistic technique, in parallel he developed another, depending on the genre specifics of a particular play.

When Yakulov turned to a tragedy that required meager formal decisions, his scenography - in "King Oedipus" or in an unrealized production of "Hamlet" - did not allow fragmentation of forms, the color conciseness of the scenery provided all the colorful power of the lighting. With even greater monumentality, Yakulov planned the pictorial solution of the opera "Rienzi", the scene of which, in an unrealized production by Meyerhold, was supposed to turn into an arena with an amphitheater. But the second version of the scenery, realized in Zimin's Free Opera, was sustained by the artist in strict forms and retained the heroic pathos of the original plan.[141]

Theoretical ideas

[edit]Despite the significant number of Yakulov's appearances in print, he did not carry out a systematic presentation of his theoretical views. The theory of "multi-colored suns", declared by him in the articles "Blue Sun" and "Ars solis. Color Painter's Sporades ", remained unfinished and, according to researchers, was not so much a theory, how much by the presentation of the artist's philosophical ideas about the stylistic differences of cultures of different regions in the bizarre terminology of his own invention.[18] According to the brief and generalizing formulation of his fellow futurist B. Livshits, Yakulov "had a kind of epistemological concept opposing the art of the West, as the embodiment of geometric perception, directed from object to subject, - the art of the East, the algebraic worldview, going from subject to object".[25] In more specific issues - distinguishing the types of painting of previous eras by the prevailing color spectra and the search for color-space solutions for modern painting of the "electric sun" - Yakulov, according to his autobiography and the testimony of M. Larionov, in the summer of 1913 he collaborated with R. Delaunay, in parallel developing their theory of simultanism,[149][150] but, unlike his French colleague, his ideas did not have a noticeable influence on the work of other artists.

At the same time, in a number of Yakulov's articles on the art of theater, the materials of his speeches, unfinished works and letters contain many theoretical statements, related to practical issues of theatrical work, often complementary to each other and in a complex constituting a single whole. At the end of a lecture given in 1926 to the troupe of the newly created Belarusian Jewish Theater Yakulov, answering the question, he makes a quick note: "We confuse kinetics with dynamics",[151] left at that moment without explanation. In the work "Theater and Painting" written shortly before his death (published in 2010 in the book by V. Badalyan) Yakulov explains in detail the connection of these conceptual concepts in his theoretical system of concepts, comprehended by him independently of the then not yet arisen kinetic art:

"Kinetics is the area of consciousness, rhyming and metering. Dynamics - winding the clock spring, kinetics - exponential movement of the hands on the dial. Dynamics exists "in spite of reason, in spite of the elements". Kinetics, on the contrary, subordinates everything to reason. and must take into account the elements. <...> In the new eccentric theater, the actor has to control the set just like a pilot an airplane. The sets and costumes must be kinetic and only one actor is dynamic".

Describing in the same lecture the pace of audience perception in different historical epochs a simple comparison of the speed of movement of a car wheel relative to a cart wheel, Yakulov makes a fundamental conclusion about the dependence of theatrical production on the specifics of the psychology of modern audience perception: "Every theater is looking for its own design, because the modern viewer, surrounded by modern everyday objects, to a certain extent accustomed, both in the sense of auditory and sound and in the sense of technology, to see things this way and not otherwise. <...> When you see this terrible speed of visual [perception] in a modern European city, experiences of impressions, then it will become quite obvious to you that the measured Greek tragedy, calculated for the whole day, is not suitable for us".[153]

In August 1925, explaining in a letter to Diaghilev the script plan for the ballet they had conceived, Yakulov notes the internal correspondence to the theme of the future production of the Introduction, just composed by Prokofiev. At the same time, in literally a few phrases, he not only expresses program ideas about the relationship of music, choreography and scenography in the production of the play, but also provides a critical overview of other points of view:

"Outside, in the sense of the external form, that is, the correspondence of music with ballet movements, managed to find what I consider the only acceptable in the new, and not in the classical ballet, and what was not understood by Tairov in the production "Girofle", namely, the parallelism of themes - musical and ballet, and not fusion. I'm talking about a lack of simultaneity or, rather, the simultaneity of themes, and the accompaniment of music is only rhythmic, not tempo. This is the true nature of dance for with the same musical theme ("Along the street paving" or "Lezginka") we see completely different performances of dance and movement. Therefore, the music should give the whole theme at once (as well as decoration), and the dance and the different characters of the movement will give the development of this theme and its variations. For the method of consonance in the bars of movement with music is duncanism, which, as a method, in the absence of barefoot and amateurishness, will give the old classicism".

— Georgy Yakulov

Articles about art

[edit]

- An artist's diary. Blue sun // Alcyone. Almanac. Book. 1. - M., 1914. - S. 233–239.[116]

- The principle of staging "Measure for Measure" // Theater Bulletin. - M., 1919. - No. 47. - P. 11.

- More about three-dimensionality // Theater Bulletin. - M., 1920. - No. 59. - P. 5–7.

- From the artist's diary // Rampa. - M., 1921. - No. 8. - P. 4.[116]

- From the artist's diary // Art and Labor. - M., 1921. - No. 1. - P. 9.

- The value of the artist in modern theater // Theater Bulletin. - M., 1921. - No. 80-81. - p. 17.

- Ars solis. Colorist's Sporades // Hotel for travelers in the beautiful. - M., 1922. - No. 1.[116]

- My counterattack // Hermitage. - M., 1922. - No. 7. - P. 10–11.

- On the problem of synthesis "East - West" // Screen. - M., 1922. - No. 22. - P. 13.

- On eccentric art // Screen. - M., 1922. - No. 31. - P. 4.

- "Signor Formica" (on the principles of Hoffmann's design) // Screen. - M., 1922. - No. 31. - P. 5.

- Two productions of the season // Teatralnaya Moscow. - M., 1922. - No. 4. - P. 12; No. 46. - P. 7.

- Ex oriente lux. "Eternal Jew", or the Second Exodus of Jews in Palestine // Spectacles. - M., 1923. - No. 43. - P. 3.[155]

- In memory of the 26 // Baku worker. - Baku, 1923, September 23.

- Revolution and art (Artist Yakulov about his project of the monument to 26) // Baku worker. - Baku, 1923, September 25.

- From the artist's diary // Spectacles. - M., 1923. - No. 69. - P. 6.

- Artist's notebook // Ramp. - M., 1924. - No. 8-21. - P. 4.[116]

- About Meyerhold's "Forest" // Spectacles. - M., 1924. - No. 72. - P. 7.

- Yakulov talks about philistinism // New ramp. - M., 1924. - No. 2. - P. 6.

- "Stenka Razin" (What is your opinion about the play?) // Spectacles. - M., 1924. - No. 73. - P. 5.

- Evaluation of artistic work // New ramp. - M., 1924. - No. 6. - P. 14.

- An artist's diary. "Man of the Crowd" // Life of Art. - P. - M., 1924. - No. 2. P. 9–10; No. 3. - P. 7–9.[116]

- Monument 26 // Baku worker. - Baku, 1924, August 25.[116]

- "Arsonists". New Drama Theater // Art for the Working People. - M., 1925. - No. 8. - P. 12.

- Sculptor Mendelevius // Krasnaya Niva. - M., 1925. - No. 6. - P. 125.

- Trial of the theatrical season // New spectator. - M., 1925. - No. 19. - P. 11.

- The paths of artistic culture in the TSFSR (Conversation with the artist Yakulov) // Dawn of the East. - Tiflis, 1926, December 15.

- Picasso // Ogoniok. - M., 1926. - No. 20. - P. 10

- About theater, cinema and art of the Transcaucasus (Fugitive notes) // Dawn of the East. - Tiflis, 1927, March 12.

- Niko Pirosmanishvili (From the cycle "East - West") // Dawn of the East. - Tiflis, 1927, March 31.[116]

- "Steel skok" S. Prokofiev // Rabis. - M., 1928. - No. 25. - P. 5.[116]

- Easelism and modernity. Artist's Notes // Art. - M., 1929. - No. 1-2. - P. 103–105.

- Arts parade and theater boundaries. Lecture (1926) // Mnemosyne: Documents and facts from the history of Russian theater of the twentieth century. Issue 5. / Publ., Entry. article and comment. V.V. Ivanova. - M .: Indrik, 2014. - P. 241–271.

- Theater and Painting (1928) // Badalyan V. Georgy Yakulov (1884-1928) Artist, art theorist. - Yerevan: Edith Print, 2010.

Gallery

[edit]Painting, graphics

[edit]-

"Cafeshantan", 1906, State Tretyakov Gallery

-

"Roosters", 1907, NGA

-

"Decorative theme", 1907, NGA

-

"Lombardy", 1912, Tretyakov Gallery

-

"Fight", 1912, State Tretyakov Gallery

-

"Battle of the Amazons", 1912, NGA

-

Monte Carlo, 1913, NGA

-

"Circus", 1910s, Museum of Arts of Uzbekistan

-

"Cafeshantan", 1912, NGA

-

"Bar", 1915, State Tretyakov Gallery

-

Panel for the cafe "Pittoresk", 1917, State Tretyakov Gallery

-

"Negro" (panel), 1917, NGA

-

"Genius of Imagism", 1920

-

Poet Rurik Ivnev, 1920, NGA

-

"Before the Mirror", 1920, NGA

Theater

[edit]-

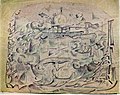

Set design for the unrealized play "Mystery-Buff", 1920, Theater Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Cemetery. Set design for the unrealized play "Hamlet", 1920, NGA

-

Set design for the play "Princess Brambilla", 1920, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Oedipus costume sketch for the play "Oedipus the King", 1920, NGA

-

Sketch of costumes for priests for the play "The Jewish Widow", 1923, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Fairy costume sketch for the play "Princess Brambilla", 1920, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Sketch of an ostrich costume for the play "Princess Brambilla", 1920, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Sketch of a carnival bout for the play "Princess Brambilla", 1920, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Sketch of a Harlequin costume for the play "Princess Brambilla", 1920, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Sketch of costumes for knights and heralds for the opera "Rienzi", 1923, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Sketch of a man's costume for the operetta "Giroflé-Girofla", 1922, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Sketch "Procession of the Moors and Murzuk" for the operetta "Girofle-Giroflya", 1922, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Sketch of costumes for Carmen and Jose for the unrealized ballet "Carmen", 1923, Museum. Bakhrushina

-

Sketch for the costume of Formica for the play "Signor Formica", 1922

-

Costume design for the unrealized play "The Seducer of Seville", 1918, Museum. Bakhrushina

Literature

[edit]- Tairov, A. Ya. (1929). "Georgy Yakulov". Journal of the Glaviskusstva Narcopros RSFSR: 73–77.

- Efros, A. M. (1934). Chamber Theater and its artists: 1914-1934. [Foreword]. pp. IX–XLVIII.

- Aladzhalov, S.I. (1971). Georgy Yakulov. Yerevan. p. 320.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Khidekel, R. P. (1971). "About three artists of the Chamber Theater. [Exter, Yakulov, Vesnin]". Iskusstvo: 37–43.

- Lapshin, V.P. (1975). Questions of Soviet Fine Arts and Architecture. p. 335.

- Strigalev, A. (1975). Problems of the history of Soviet architecture. Issue 3.

- Kostina, E.M. (1979). Georgy Yakulov. 1884-1928.

- Denisovsky, N.F. (1983). Panorama of Arts. Issue 6. p. 384.

- Sarabyanov, D.V. (1987). Soviet painting. Issue 9. M.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Livshits, B.K. (1989). One and a half-eyed Sagittarius: Poems, translations, memoirs. Л. p. 720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kovtun, E. F.; Nerler, P. M.; Parnis, A. E. (1989). Livshits B. K. Half-eyed Sagittarius: Poems, translations, memoirs. L. p. 720.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Strutinskaya, E. I. (2008). ""Fortunately, there are Russians." Section of the Soviet theater at the 1925 International Exhibition of Decorative Arts and Art Industry in Paris" (PDF). Theater Questions: 152–192.

- Badalyan, V. (2010). Georgy Yakulov (1884-1928) Artist, art theorist. Yerevan. p. 168.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sidorina, E.V. (2012). Sidorina E.V. Constructivism without shores. Studies and studies on the Russian avant-garde. Yerevan. p. 656. ISBN 978-5-89826-365-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Kovalenko, G. F. (2012). ""All wheels will turn ...": Georgy Yakulov - designer of the "Steel Skok" ballet" (PDF). Theater Issues. 1–2: 274–303.

- Ivanov, V.V. (2014). Parade of Arts and Theater Borders. G.B. Yakulov. Lecture (1926) // Mnemosyne: Documents and facts from the history of Russian theater of the twentieth century. Issue 5. Yerevan. p. 800.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vakar, I. A. (2016). "Master of colorful suns". Our Legacy: 138–157.

- Marcadé, Jean-Claude (1972). "Des lumières du soleil aux lumières du théâtre: Georges Yakoulov". Cahiers du monde russe et soviiers. 13: 5–23. doi:10.3406/cmr.1972.1866.

- Press, Stephen (2005). "By way of Le Pas d'acier Prokofiev and Iakulov's Ursiniol comes to the stage". Three Oranges: 5–23.

References

[edit]- ^ Ivanov 2014, p. 245.

- ^ a b Tairov 1929, p. 74.

- ^ Vakar 2016, pp. 142–148.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 30–31, 303.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 33-34.303.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 34–37.

- ^ a b c Kostina 1979, pp. 5–19.

- ^ Tairov 1929, p. 73.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Vakar 2016, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 38–39.

- ^ P. Muratov Old and young at the last exhibitions |"Golden Fleece", 1908, No. 1 (January), p.89.

- ^ Vakar 2016, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Tairov 1929, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Kostina 1979, p. 73.

- ^ Vakar 2016, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Vakar 2016, pp. 144–146.

- ^ a b Kovtun, Nerler & Parnis 1989, p. 678.

- ^ Kostina 1979, pp. 73, 196–197.

- ^ Elsner V. Purple Kiefer. Erotic / front. N. Milioti, ill. M. Saryan and G. Yakulov. - M .: Book publishing "Alcyone", 1913.

- ^ Kovtun, Nerler & Parnis 1989, pp. 676–678.

- ^ Livshits 1989, pp. 465–469.

- ^ Kovtun, Nerler & Parnis 1989, p. 679.

- ^ a b Livshits 1989, p. 468.

- ^ Kovtun, Nerler & Parnis 1989, p. 676.

- ^ Vakar 2016, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Rodchenko A.M. Experiments for the future. - M., Grant, 1996. — P. 212.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 49–54, 306–307.

- ^ Kostina 1979, pp. 196–197.

- ^ a b Kostina 1979, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Sidorina 2012, p. 540.

- ^ Kostina 1979, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, p. 56.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, pp. 540–542.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, pp. 542–543, 556, 648.

- ^ The fact that Tatlin took a demonstratively performing position is evidenced by the conflict described by A. Rodchenko between Tatlin and Yakulov at the stage of remuneration, when "painter Tatlin" demanded that Yakulov pay him for the "painting work" performed - Sidorina, 2012, p. 648.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, p. 57.

- ^ Denisovsky 1983, p. 202.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, p. 546.

- ^ Efros 1934, p. XXXI.

- ^ Yakulov reported about this threat in his letter to the People's Commissar Lunacharsky - see: Mass propaganda art of the first years of October ". - M., 1971. -P. 128.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, p. 649.

- ^ Ivanov 2014, p. 261.

- ^ Kostina 1979, p. 75.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, p. 58.

- ^ Esenin S. Collected works in 5 volumes. T. 5. - M., GIHL, 1962. - P. 219-223, 385-386

- ^ Cafe Pegasus' Stable occupied the basement of the pre-revolutionary cafe Bom, at the corner of house No. 37 on Tverskaya Street, with an exit to Maly Gnezdnikovsky Lane (the building has not survived, in its place in 1940 the existing building 17 was built).

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 116–117, 308.

- ^ a b Aladzhalov 1971, p. 308.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 117, 309–310.

- ^ Kostina 1979, p. 14.

- ^ Denisovsky 1983, p. 201.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 308, 309.

- ^ a b Kostina 1979, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b Denisovsky 1983, p. 204.

- ^ Penguin [Shershenevich V.G.] Yakulovization of theaters // Spectacles. - M., 1923. - No. 23 (6-12 Feb.) - P. 14-15. - Ivanov, p.241,261

- ^ a b c d e Kostina 1979, pp. 200–206.

- ^ The State Demonstration Theater, organized by V. Sakhnovsky, opened in October 1919, G. Yakulov was a member of the theater management board; the premiere of the performance took place on November 25, 1919 - Aladzhalov, 1971, p.308

- ^ "Portrait of the actor M.F. Lenin in the role of Angelo. Theater Museum named after Bakhrushin". Archived from the original on 2019-06-22. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

- ^ a b c Ivanov 2014, p. 241.

- ^ "Tairov subordinated the performance to the theme of the Venetian carnival, organized by the rhythm of the tarantella"; premiere: May 4, 1920 - Ivanov, 2014, p. 241,263.

- ^ Set design. "The stage of the magician." Archived 2019-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. Bakhrushin Theater Museum.

- ^ Ivanov 2014, p. 264.

- ^ Meyerhold rejected Yakulov's layout for the second edition of Mystery Buff (due to differences in the understanding by the masters of constructivism), but planned to use it when staging Wagner's Rienzi, but the opera was presented only in concert - Ivanov, 2014, p. 241,262.

- ^ Ivanov 2014, pp. 241, 264.

- ^ Premiere of the play: June 13, 1922 - Costume design for four academicians Archived 2019-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. Theater Museum. Bakhrushin.

- ^ Premiere of the play: October 3, 1922 - Ivanov, 2014, p.262.

- ^ a b Denisovsky 1983, p. 205.

- ^ Sketch of men's suits Archived 2019-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. Theater Museum. Bakhrushina.

- ^ Premiere of the performance: June 5, 1923 - Ivanov, 2014, p.241,265.

- ^ Sketch of men's suits Archived 2019-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. Theater Museum. Bakhrushina.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, p. 311.

- ^ Sketch of men's suits Archived 2019-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. Theater Museum. Bakhrushina.

- ^ City. Costume design for King Lear Archived 2019-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. St. Petersburg Museum of Theater and Musical Art.

- ^ Premiere of the play: March 26, 1926 - Ivanov, 2014, p. 241,266.

- ^ City. Scenery sketch Archived 2019-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. Theater Museum named after Bakhrushin.

- ^ The Jewish studio, which came from Minsk to Moscow in 1926 to study, was reorganized in the fall into the Belarusian State Jewish Theater (BelGOSET); it was in the process of working on "Shylock" that the artist read the lecture "The Parade of Arts and the Frontiers of Theater" to the troupe of the Jewish theater - Ivanov, 2014, p. 241—242.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, p. 111.

- ^ V. M. Khodasevich Portraits with words. Essays. — M., 1995. — P.141.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, p. 106.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Marcadé 1972, pp. 8/9, Ph.3.

- ^ Kostina 1979, pp. 75, 200.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, p. 551.

- ^ Kostina 1979, pp. 75–76, 200.

- ^ A project by F.O.Shekhtel and a sketch by B.L. Lopatinsky - Aladzhalov, 1971, p. 96.

- ^ One of the variants of this draft design was published on October 21, 1923 on the cover of the magazine "Ogonyok" (No. 30).

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 97, 310–311.

- ^ a b Vakar 2016, pp. 149–152.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 98–101.

- ^ a b Kostina 1979, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Yesenin S. Collected works in 5 volumes. T. 2.- M., GIHL, 1961.- P. 178.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 102, 311.

- ^ In the architectural section, a model of the monument was exhibited, in the theatrical section - a model for the play "Girofle-Giroflya": Exposition de 1925 : Section URSS : catalogue : Exposition internationale des arts decoratifs et industriels modernes (1925 : Paris, France) : [фр.] : Section de l’Union des Republiques Sovietistes Socialistes. Academie russe des Sciences de l’Art, State academy artistic sciences. Paris, 1925. — Moscou, [1925]. P. 111,172.

- ^ Composer S. Prokofiev, in his diaries of the summer of 1925, mentions "a number of models" of Yakulov's decorations for Moscow theaters at the World Exhibition - Kovalenko, 2012, p. 278.

- ^ Strutinskaya 2008, p. 167.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 309–310.

- ^ D. Shterenberg was the chairman of the selection committee, his deputy was A. Rodchenko, the committee also included 13 members: A. Vesnin, N. Punin, J. Tugendhold, D. Arkin, S. Gerasimov, G. Yakulov and others

- ^ Strutinskaya 2008, p. 157.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 129, 211.

- ^ Strutinskaya 2008, p. 162.

- ^ Strutinskaya 2008, p. 170.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, p. 312.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, pp. 551–552.

- ^ Kovalenko 2012, pp. 281–285.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, p. 552.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 102–103, 311.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 23, 312.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 145–159, 161–172.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 175–179, 183–185.

- ^ At the premiere performance, "applause lasted throughout the entire performance. Yakulov <…> was summoned by the public 8 times "-" Lunacharsky A. "Politics and the public (from Parisian impressions) // Red Panorama. - 1927. - No. 33.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 204, 207.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 8, 207, 220–224.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 213, 256, 314–315.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i The text was reprinted in the book: Kostina, 1979, pp. 73-93.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 256, 315.

- ^ Gilyarovskaya N. Death of the artist Yakulov // Vechernyaya Moskva, December 29, 1928

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 264–269.

- ^ Denisovsky 1983, p. 206.

- ^ Denisovsky 1983, pp. 206–207.

- ^ The funeral of the artist Yakulov // Izvestia, January 8, 1929

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, pp. 284–287.

- ^ Aladzhalov 1971, p. 286.

- ^ a b Kostina 1979, p. 19.

- ^ Vakar 2016, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Bulletin of the Society of Friends of Yakulov: Notes et documents, no. 3, Paris, juillet 1972, p. 35

- ^ Georgy Yakulov at the Center Pompidou (Paris).

- ^ Kovalenko 2012, p. 296.

- ^ Kovalenko 2012, p. 282—285.

- ^ Kostina 1979, p. 197.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, p. 539.

- ^ Kostina 1979, p. 11.

- ^ Vakar 2016, pp. 148–150.

- ^ Denisovsky 1983, pp. 200–201.

- ^ The three-part painting by G. Yakulov "There lived a poor knight" (1910-1911) in 1967 was in France, in the collection of A. K. Larionova-Tomilina; her further fate is unknown - Vakar, 2016, p. 159.

- ^ Kovalenko 2012, p. 290.

- ^ Kostina 1979, pp. 10–14.

- ^ Vakar 2016, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, pp. 545, 556.

- ^ a b c Kostina 1979, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Ivanov 2014, p. 244.

- ^ Sidorina 2012, pp. 548, 550.

- ^ Efros 1934, p. XXXVI.

- ^ Dynamics and kinetics in the understanding of Yakulov constituted various types of movement in theatrical art; see the Theoretical Ideas section.

- ^ Kovalenko 2012, pp. 288–291.

- ^ Kovalenko 2012, p. 297.

- ^ Tairov A. In memory of Yakulov. - Contemporary theater. - M., 1929. - No. 3. - P. 37.

- ^ Kovtun, Nerler & Parnis 1989, pp. 677–678.

- ^ Vakar 2016, pp. 145–147.

- ^ Ivanov 2014, p. 257.

- ^ Badalyan 2010, p. 99.

- ^ Ivanov 2014, pp. 252–253.

- ^ Kovalenko 2012, p. 284.

- ^ Ivanov 2014, p. 265.

Links

[edit]- 1884 births

- 1928 deaths

- Russian painters

- Armenian painters

- Soviet painters

- Russian scenic designers

- Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery

- Georgian people of Armenian descent

- Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture alumni

- Academic staff of Stroganov Moscow State Academy of Arts and Industry

- Mir iskusstva artists