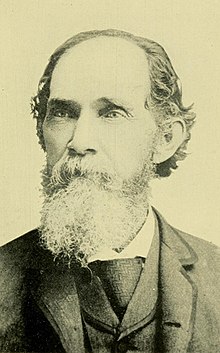

George Wythe Baylor

George Wythe Baylor | |

|---|---|

George W. Baylor | |

| Member of the Texas House of Representatives from the 80th district | |

| In office January 11, 1887 – January 8, 1889 | |

| Preceded by | John Bailey |

| Succeeded by | George B. Stevenson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 24, 1832 Fort Gibson, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory |

| Died | March 24, 1916 (aged 83) San Antonio, Texas, US |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 2nd Texas Cavalry Regiment (Arizona Brigade) |

| Battles | |

George Wythe Baylor (August 24, 1832 – March 24, 1916) was a Confederate cavalry officer from Texas, and a veteran of many battles of the American Civil War. He was also a noted lawman and frontiersman with the Texas Rangers.

Born at Fort Gibson, Indian Territory, in 1832, Baylor came to Texas at the end of 1845 as a boy and was educated there. After the outbreak of the Civil War, he enlisted in the Confederate States Army, and was elected first lieutenant, 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles. He witnessed the death of General Johnston at Shiloh, and fought in many engagements of the Red River campaign in Louisiana in 1864. He was promoted to major, and later colonel, by President Davis, although his promised regiment of Texas Rangers was never raised owing to the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865.

After the war, Baylor commanded Texas Rangers in hunting Comanches and Apaches in Texas and across the border into Mexico, often in pursuit of the Apache chief Victorio and his raiding band. He was also an elected representative of the Texas State Government, representing El Paso from 1887 to 1889. He later retired to Guadalajara, Mexico, and lived there for some years, but was compelled to return to the United States in 1913 due to the Mexican Revolution. He died in San Antonio in 1916.

Early life

[edit]George Wythe Baylor was born at Fort Gibson, in the Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, on August 24, 1832.[1] His father, an army surgeon in the 7th Infantry Regiment,[2][3] was John Walker Baylor, eldest son of Major Walker Baylor, of Bourbon County, Kentucky, whose wife was Jane, née Bledsoe, a sister of Jesse Bledsoe, of Kentucky.[1] The Baylor lineage traces their origin to Devon, England.[4] His mother was Sophia Maria, née Weidner, of Baltimore, Maryland, her father being Henreich Weidner, of Hessen Cassel, Germany, and her mother being Marie Chartelle, of an old Huguenot family.[1][5] He was their fifth son and eighth child.[6]

His father moved from Bourbon county, Kentucky, to Fort Gibson, with his young family, going down from Louisville to the mouth of the Arkansas River on a keel boat, and this boat was dragged up the river to Fort Gibson.[7] His mother took along a lot of fruit trees, roses and plants.[7]

His father dying when he was four years old, his mother, then living on Second Creek, Mississippi, near Natchez, went to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, then to Little Rock, and finally to Fort Gibson again.[7] In December 1845, Baylor came to Texas while still a boy, stopped at Ross Prairie, Fayette county, and went to school for a while to Professor William Halsey at Rutersville, and afterwards was sent by his uncle, Judge R. E. B. Baylor, to Baylor University, at Independence, Texas, then under the control of Henry Graves.[7]

He went from school to San Antonio, and, lured by the gold rush, left there in March 1854 for California, five months being required to make the trip.[7] He remained in California five years, and, although brought out by the Democratic party in 1859 for the Legislature, he preferred to come back to Texas.[7] Returning to San Antonio in May 1859, he left for Parker county.[7]

In 1860 he commanded a company of rangers in what was known as the Buffalo Hunt.[7] There were some 300 men in the expedition,[7] and Baylor he was leader of a company of 33 frontiersmen.[8] The Comanches generally gave them a wide berth, although Baylor's men killed some Comanche men.[7] The rangers discovered the scalps of a babe and a woman with braided hair, both adorning the shield of a chief whom they had killed.[9] The campaign lasted six weeks and was the first extended service which Baylor saw.[8] In the same year, Baylor's profession was listed on the Parker county tax records and the United States census as "Indian killer".[7] The rangers also practiced scalping, and, as Baylor later explained, for the benefit of his "eastern friends", this was to manipulate the Comanches' fear of losing their scalps—without which they could not hope to enjoy the best pleasures of their afterlife.[10]

Civil War

[edit]

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Baylor enlisted in the Confederate States Army, joining Captain Hamner's company (Company H, 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles) at Weatherford on March 17, 1861, and was elected first lieutenant, the company being attached to Colonel John S. Ford's regiment of cavalry.[7][11] He enlisted for three years and was sworn in as first lieutenant of his company in San Antonio in May 1861.[8][11] His brother, John R. Baylor, was lieutenant colonel of the regiment.[8] He went with his company to Fort Clark, and from there went to El Paso as his brother's adjutant.[8]

Ford's regiment had four companies.[11] It went to El Paso, there became Pyron's regiment and enlisted more men and companies, and then went to Louisiana under General Thomas Green.[11]

Shortly after his arrival in El Paso the first regiment of the Union Army Baylor was called upon to fight was that to which his father had been attached during his lifetime, the 7th Infantry, and he and his brother had relatives and a large number of friends in its ranks.[8] Though there were 750 men in the Union forces and a little over 300 in those of the Confederates, after a short struggle the entire Union regiment was captured.[8]

From this time Baylor's advancement in rank was rapid.[8] After being stationed for a short time at San Augustine Springs, in New Mexico (afterwards Cox's ranch), he received an appointment from General Albert Sidney Johnston as his chief aide-de-camp and went to join Johnston's staff at Bowling Green, Kentucky.[8] He remained on Johnston's staff until the general was killed at Shiloh, and held his head in his dying moments.[8][7]

After General Johnston's death Jefferson Davis promoted Baylor to the rank of major, with authority to raise a battalion of Texas rangers for service in the Confederate cause.[8] The battalion was later increased to a regiment and Baylor's rank raised to that of colonel (2nd Arizona Regiment) by President Davis's order.[8][11]

Baylor was present at the capture of the United States regulars near Fort Fillmore in New Mexico, and in the following fights in the Louisiana Red River campaign: Mansfield, Pleasant Hill, Monett's Ferry, Marksville, Mansura and Yellow Bayou.[11][5] He took part in the pursuit of Union General Banks.[11] Since Colonel Walter P. Lane was wounded at Mansfield, Baylor took command of the brigade until the close of the Red River campaign.[11] Baylor's brigade captured the City Belle and the troops aboard on May 3, 1864. His brigade destroyed the USS Covington, and captured the USS Signal and transport John Warner on May 5, 1864.[12][13] His troops captured the Warren, a steamboat loaded with supplies and troops going up the Red River in Louisiana.[11] At the battle of Mansfield his regiment was in Lane's brigade which struck the right wing of the Union force.[14] Mansfield was a smashing Confederate success, with the victors capturing 1,541 Union soldiers, 20 cannons, and 175 wagons.[15] However, Confederate losses were substantial, including General Alfred Mouton killed.[16] At the battle of Monett's Ferry, Baylor was assigned to take command of the left flank of the Confederate force.[17][18]

While the promised regiment of Texas rangers was never raised, because of the coming of the close of the Civil War, Colonel Baylor retained his rank, and it was a dispute over this that led him to kill General John A. Wharton during a heated quarrel on April 6, 1865,[8] at the headquarters of General John B. Magruder in the Fannin Hotel in Galveston.[5] They argued, reportedly about "military matters" related to the reorganization of the Trans-Mississippi Department, and Wharton repeatedly struck Baylor in the face, calling him a liar; then Baylor drew his revolver and shot Wharton, who was unarmed and died instantly.[5] Baylor was tried three times before he was finally acquitted after the war.[8]

By his own account, Baylor was never wounded or made prisoner, but was badly scared by being hit on the nose at Shiloh on April 6, 1862, and had a horse shot under him at Yellow Bayou, Louisiana, in 1864.[11]

Texas Rangers

[edit]

After the close of the war Baylor lived in Galveston, Dallas and San Antonio, and in 1879 was sent out as second or junior lieutenant of Company C (Harrington's company), Texas Rangers, to El Paso, by Governor Roberts.[19][8] Baylor left San Antonio on August 2, 1879, with his wife, two young daughters, and sister-in-law, two fully laden wagons, a piano, and a game cock with four hens.[5]

This was just after Mexicans had killed a number of Americans at San Elizario, El Paso County, and there was much excitement along the border.[8] His first fight with the Apaches was on October 7, three weeks after he got to his post,[19] when the Apaches made a raid.[8] One Mexican had been killed by the Apaches and a party of Mexicans went along with the Rangers in pursuit of them across the Rio Grande into Mexico.[8] Overtaking the band at 11 am, they fought with them until dark, killing three Apaches.[8] One horse killed was the Rangers' total loss.[8]

It was shortly after this that Baylor had his first experience with Victorio and his band of Apaches.[8] The band had killed 33 of the citizens of the town of Carrizal (near what is now Villa Ahumada) in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico.[8][19] A party of 15 had gone out against the Apaches, and had all been killed, and a relief party of 18 that had gone out in search of the first party had also been killed by the Apaches.[8] The citizens of El Paso del Norte (now Juarez) organized and asked Baylor and his Rangers to join their party to go in pursuit of Victorio.[8] Baylor consented, and when the two parties got together the Mexicans wanted him to take full charge of the expedition.[8] Baylor, however, objected that, they being on Mexican soil, a Mexican ought to command, whereupon an old pioneer Mexican, Francisco Escajeda, was made leader, and Baylor served as second in command.[8] Nothing came of the expedition, however, for, upon scouring the neighborhood of the raid, it was found that the Apaches had crossed over again into New Mexico, and could not be located.[8][5] Thirty-two bodies of the Mexicans were found and buried.[8] A number of saddles were also found.[8]

Another expedition into Mexico that came to naught for the Americans, soon followed.[8] In the meantime Baylor had been made captain of Company A, Texas Rangers.[8][5] With 20 rangers under his command, Baylor joined Colonel Joaquin Terrazas, described by the El Paso Herald as "an old Indian fighter", in Chihuahua.[8] The United States army sent Lieutenant Parker with 68 Chiricauhua Apache Scouts also to join Terrazas, and 20 black soldiers under Lieutenant Manney, to aid in the campaign against the Apaches.[8] After following the trail of the Apaches for some time, they succeeded in locating them, but the Mexicans became uneasy because of the presence of the Chiricauhua Apaches in the party and expressed the fear that they would side with Victorio should he make a good showing in a fight.[8] "For they are relatives," said the Mexicans.[8] On the other hand, they argued if Victorio was defeated the Chiricauhua Apaches would want all the saddles.[8] For these and probably other reasons, Terrazas announced that he had orders to not allow the Americans to remain on Mexican soil, and so the rangers and the United States troops withdrew, while Terrazas and his Mexicans met Victorio at Tres Castillos, and killed a great number of the Apaches, nearly annihilating the band.[8]

The final extermination of Victorio's band came about as the result of the Apaches attacking a stage coach in Quitman canyon,[a] killing the driver, whose name was Morgan, and a passenger named Crenshaw.[8][20] Baylor went to the scene with 15 men and took up the trail of the Apaches.[8] He followed them for three days into Mexico and then back again into the United States.[8][20] He then telegraphed to Lieutenant Charles Nevell, who afterwards served as sheriff of El Paso County, and Nevell met him with 10 men at Eagle Springs.[8] The joint party again took up the trail, and overtook the Apaches at daybreak.[8] A small but bloody fight ensued on the morning of January 29, 1881,[20] in which all of the Apaches were either killed or wounded.[8] A woman[b] and two children, a boy and a girl, were captured.[8] This was the last such raid in Texas, and was the end of Victorio's band.[8][20]

Baylor was then placed in command of the Texas Rangers, with the rank of major, in command of a battalion to put down fence-cutting during the trouble which resulted from this practice.[8][5] He saw active service in that capacity, making a raid on an organized band in Nolan County which resulted in nine arrests.[8][19]

Later life

[edit]

After this his active fighting service ended.[8] He resigned from the ranger service in 1885.[5] He was a member of the Texas state Legislature, elected in 1886 from El Paso (80th district), where he had lived for many years and was well known, to serve in the Texas House of Representatives, and was a prominent member in the House.[21][19] He served from January 11, 1887, to January 8, 1889.[21] He was also clerk of the district and circuit courts for some years.[20]

At some point Baylor left El Paso, and went to Guadalajara, Mexico, which was his home prior to the disruption of the Madero revolution, and where, except for visits to the United States and short residence in El Paso, he lived until ordered to leave the country by President Wilson in 1913.[8] While living in El Paso and after he went to Mexico, he was a frequent contributor of early reminiscences of the border to the El Paso Herald.[8] He died at San Antonio, Texas, on March 24, 1916, aged 83 years.[8] He was interred beside fellow Civil War veterans in the Confederate Cemetery in San Antonio.[20] A subordinate once called him "a hardy frontiersman who cared nothing for discipline … one of the best shots with firearms I ever saw."[22]

Personal life

[edit]

Baylor married Sallie (Sally) Garland, née Sydnor, of Houston, Texas, in 1863.[23] Their children were:

- Hel(l)en, born December 10, 1865;

- Sophie Marie, died in infancy;

- Mary Courtenay, born June 11, 1874.[23]

Of the foregoing children, Helen was married three times: first, to James Gillett; second, to Captain Frank Jones of the Texas rangers, who was killed in a skirmish with a band of outlaws; third, to Captain Merwin Lee.[23] By her first husband, she left one son, Harper Gillett, and also a son by her second husband, Frank Jones.[23] She died at Monterey, Mexico, on May 25, 1903.[23] Colonel Baylor's wife, Sallie, died in Guadalajara, Mexico, in 1904, and was buried there.[23]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Daniell 1887, p. 104.

- ^ Webb 1993, p. 395.

- ^ Waller 1943, p. 23.

- ^ Genealogy of the Fitzhugh-Knox-Gordon-Sevier families. Foote & Davies. 1932. p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cutrer 2017.

- ^ Baylor; Baylor 1914, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Daniell 1887, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba El Paso Herald, April 2, 1916. p. 7.

- ^ Marshall 1990, p. 108.

- ^ Marshall 1990, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Yeary, ed. 1912, p. 45.

- ^ Smith 2010, pp. 214–216.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, p. 91.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, p. 104.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, p. 97.

- ^ Scott, ed. 1891, p. 616.

- ^ Brooksher 1998, pp. 179–181.

- ^ a b c d e Daniell 1887, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d e f Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum.

- ^ a b Legislative Reference Library of Texas.

- ^ Allardice 2008, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f Baylor; Baylor 1914, p. 32.

Sources

[edit]- Allardice, Bruce S. (2008). "Baylor, George Wythe". Confederate Colonels: A Biographical Register. Columbia and London, MO: University of Missouri Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780826266484.

- Baylor, Orval Walker; Baylor, Henry Bedinger (1914). "Children of John W. Baylor, First Son of Walker Baylor". Baylor's History of the Baylors, 1550–1914. LeRoy Journal Printing Company. pp. 29–32.

- Brooksher, William Riley (1998). War Along the Bayous: The 1864 Red River Campaign in Louisiana. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's. pp. 131, 179, 180, 220. ISBN 1-57488-139-6.

- Cutrer, Thomas W. (January 31, 2017). "Baylor, George Wythe (1832–1916)". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved April 5, 2023.

- Marshall, Doyle (1990). A Cry Unhead: The Story of Indian Attacks In and Around Parker County, Texas, 1858–1872. Aledo, TX: Annetta Valley Farm Press. pp. 68, 108, 112–113.

- Daniell, L. E. (1887). "George Wythe Baylor" (PDF). Personnel of the Texas State Government, XXth Legislature. Austin, TX: Press of the City Printing Company. pp. 104–106.

- Scott, Robert N., ed. (1891). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I. Vol. XXXIV. Part I. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 112, 167, 616, 625.

- Smith, Myron J. Jr. (2010). Tinclads in the Civil War: Union Light-Draught Gunboat Operations on Western Waters, 1862–1865. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. p. 216. ISBN 9780786457038.

- Waller, John L. (June 1943). "Colonel George Wythe Baylor". The Southwestern Social Science Quarterly. 24 (1): 23–35. JSTOR 42865033.

- Yeary, Mamie, ed. (1912). "Col. George Wythe Baylor". Reminiscences of the Boys in Gray. Dallas, TX: Smith & Lamar. p. 45.

- "Col. George Baylor Pioneer, Is Dead". El Paso Herald. April 2, 1916. p. 7.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "George W. Baylor". Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum. Waco, TX. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- "George Wythe Baylor". Legislative Reference Library of Texas. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Bailey, Anne J. (1989). Between the Enemy and Texas: Parsons's Texas Cavalry in the Civil War. Fort Worth, TX: Texas Christian University Press.

- Bartholomew, Ed (1958). The Biographical Album of Western Gunfighters. Frontier Press of Texas.

- Baylor, George W. (December 1897). "With Gen. A. S. Johnston at Shiloh". Confederate Veteran. 5 (12): 609–613.

- Baylor, George W. (December 1905). "The Last Fight on Texas Soil Between the Apaches and Texas Rangers". The Texas Rangers Association. 5: 18–19.

- Baylor, George W. (1966). Faulk, Odie B. (ed.). John Robert Baylor: Confederate Governor of Arizona. Tucson, AZ: Arizona Pioneers' Historical Society.

- Baylor, George W. (1996). Thompson, Jerry D. (ed.). Into the Far, Wild Country: True Tales of the Old Southwest. El Paso, TX: Texas Western Press.

- Baylor, W. K. (January 1925). "The Old Frontier; Events of Long Ago". Frontier Times. 2 (4): 8–9.

- Baylor, W. K. (February 1925). "The Old Frontier; Events of Long Ago". Frontier Times. 2 (5): 16–17.

- Baylor, W. K. (March 1925). "The Old Frontier; Events of Long Ago". Frontier Times. 2 (6): 37–39.

- Bunting, Robert Franklin (2006). Cutrer, Thomas W. (ed.). Our Trust is in the God of Battles: The Civil War Letters of Robert Franklin Bunting, Chaplain, Terry's Texas Rangers, C.S.A. Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press. pp. 334, 402. ISBN 9781572334588.

- Cunningham, Eugene (1996). Triggernometry: A Gallery of Gunfighters. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 196–202. ISBN 9780806128375.

- Gillett, James B. (1921). Six Years with the Texas Rangers, 1875 to 1881. Austin, TX: Von Boeckmann-Jones Co. pp. 148, 197–325.

- Gillett, James B. (February 6, 1926). ""Injun Fightin'" with the Texas Rangers". The Literary Digest. 88 (6): 41–50.

- Glasrud, Bruce A.; Weiss, Harold J. Jr., eds. (2012). Tracking the Texas Rangers: The Nineteenth Century. Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press. pp. 268, 276. ISBN 9781574414653.

- Haynes, Sam W.; Wintz, Cary D., eds. (2002). Major Problems in Texas History. United States: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. pp. 272, 281–284. ISBN 9780395858332.

- Hudgins, Merle Reue (2017). War Between the States Changed Texas Forever: A Study of Pre Civil War, Civil War and Post Civil War. Vol. 2. Harvard Houston, TX: Kemp & Company. p. 563.

- Jones, James P.; Keuchel, Edward F., eds. (1975). Civil War Marine: A Diary of the Red River Expedition, 1864 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: USMC History and Museums Division.

- King, Wilburn Hill (1898). "The Texas Ranger Service and History". In Wooten, D. G. (ed.). A Comprehensive History of Texas, 1685 to 1897. Vol. 2. Dallas, TX: William G. Scarff. pp. 329–367.

- Lea, Tom (1965). Ranger Escort West of the Pecos. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292770034.

- Mangum, Neil C. (1997). "[Review of Into the Far Wild Country]". The Journal of Arizona History. 38 (4): 408–409. JSTOR 41696389.

- Matthews, James T. (August 1991). Major's Confederate Cavalry Brigade (PDF) (MA thesis). Texas Tech University.

- Matthews, James T. (April 11, 2011). "Second Texas Cavalry, Arizona Brigade". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- McLeary, J. H. (1898). "History of Green's Brigade". In Wooten, D. G. (ed.). A Comprehensive History of Texas, 1685 to 1897. Vol. 2. Dallas, TX: William G. Scarff. p. 737.

- Metz, Leon Claire (2003). "Baylor, George Wythe". The Encyclopedia of Lawmen, Outlaws, and Gunfighters. New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 17–18.

- Noirsain, Serge, The Arizona Brigade: The Legion That Never Set Foot in the Desert (PDF), translated by Hawkins, Gerald, Confederate Historical Association of Belgium, pp. 8–9, 16

- Robinson, Charles M. III (2000). The Men Who Wear the Star: The Story of the Texas Rangers. New York, NY: Random House. p. 241. ISBN 9780679456490.

- Selcer, Richard F. (December 31, 2019). "In the Confederacy's Last Days, Two Texans Face Off in Futile Feud". HistoryNet. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- Smith Jr., Myron J. (2015). "Baylor, George Wythe". Civil War Biographies from the Western Waters. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 19. ISBN 9781476616988.

- Thrapp, Dan L. (1974). Victorio and the Mimbres Apaches. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 252–255, 293–300. ISBN 9780806110769.

- Thrapp, Dan L. (1990). "Baylor, George Wythe". Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography. Vol. 1. Spokane, WA: The Arthur H. Clark Company.

- Utley, Robert Marshall (2002). Lone Star Justice: The First Century of the Texas Rangers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 207, 216, 335. ISBN 978-0-19-512742-3.

- Vance, Mike; Lomax, John Nova (2014). Murder & Mayhem in Houston: Historic Bayou City Crime. Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 27–32. ISBN 9781626195219.

- Webb, Walter Prescott (1993). The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 395–406, 408, 444, 454.

- Wilkins, Frederick (1999). The Law Comes to Texas: The Texas Rangers, 1870–1901. Austin, TX: State House Press. pp. 196–198, 221.

- Wooten, D. G., ed. (1898). "Texan Troops in the Confederate Army". A Comprehensive History of Texas, 1685 to 1897. Vol. 2. Dallas, TX: William G. Scarff. p. 614.

- Wright, Marcus J.; Simpson, Harold B. (1965). Texas in the War, 1861–1865. Hillsboro, TX: Hill Junior College Press.

- "Governmental". Austin Weekly Statesman. December 30, 1886. p. 6.

- "Indian Fighter Is Called to Reward / Col. G.W. Baylor, Veteran of Many Battles, Is Dead". San Antonio Express. March 28, 1916. p. 10.

- "Of a Noted Military Family". Confederate Veteran. 6 (4): 164–165. April 1898.

- "Texas Lawmen / Major George Wythe Baylor". The Texas Observer. October 13, 1961. p. 6.

- "Wife of Colonel G. W. Baylor". Confederate Veteran. 13 (4): 176. April 1905.

External links

[edit]- "Colonel George Wythe Baylor". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- "Colonel George Wythe Baylor". Texas Historical Markers. Retrieved March 23, 2023.

- "Gen. Johnston's Senior Aide-de-Camp Murders Confederate General". Shiloh National Military Park. May 20, 2015. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- "George Wythe Baylor (1832–1916)". The Latin Library. Retrieved March 18, 2023.

- "Tom Lea, Ranger Escort West of the Pecos, 1965". El Paso History Alliance. November 3, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- 1832 births

- 1916 deaths

- Confederate States Army officers

- Members of the Texas Ranger Division

- Democratic Party members of the Texas House of Representatives

- People of Texas in the American Civil War

- American people of German descent

- American people of French descent

- American expatriates in Mexico

- American people of English descent

- American people acquitted of murder

- 19th-century members of the Texas Legislature