Genesis creation narrative: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 354745592 by EGMichaels (talk) If that's really your intent, do it on the talk page where it can be discussed. |

MarkBrownlee (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[File:Creation of Light.png|right|250px|thumb|''The Creation of Light'' by [[Gustave Doré]].]] |

[[File:Creation of Light.png|right|250px|thumb|''The Creation of Light'' by [[Gustave Doré]].]] |

||

The '''Genesis [[creation |

The '''Genesis [[creation account]]'''<ref name="account" group="note"/><ref>{{cite book | last = Browning | first = W. R. F. | authorlink = W. R. F. Browning | coauthors = | title = A Dictionary of the Bible (myth) | publisher = Oxford University Press | year = 1997 | location = | pages = | url = http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t94.e1296 | doi = | id = | isbn = 978-0192116918}}</ref> is the [[Bible|biblical]] account of the beginnings of the [[Earth]], [[life]], and [[human]]ity as described in the first two chapters of the [[Book of Genesis]]. It is considered a sacred narrative<ref>Dundes, Alan. ''Sacred Narrative: Readings in the Theory of Myth.'' University of California Press, 1984. ISBN-13: 978-0520051928</ref>{{rp|p.9}} in [[Judaism]], and [[Christianity]], but not [[Islam]], as the Quranic account of creation is substantially different. |

||

Traditionally viewed by Jews (and still viewed that way by [[Orthodox Jews]]) as having been authored by [[God in Judaism|God]], it was later adopted by Christians as well. The Genesis creation narratives have had an exceptionally long and complex history of interpretation. Until the latter half of the 19th century, they were seen as one continuous, uniform story with {{Bibleref2|Genesis|1:1–2:3}} outlining the world's origin, and {{Bibleref2-nb|Genesis|2:4–2:25}} carefully painting a more detailed picture of the creation of humanity. However, recent scholarship opines that there are two unique accounts of creation, persuaded by the use of two different names for God the creator, two different emphases (physical vs. moral issues), and a different order of creation (plants before humans, plants after humans). Today, it is nearly universally accepted that Genesis contains two distinct creation narratives, written many years apart by two different sources, each of which experienced a distinct historical climate.<ref>Segal, Robert A. ''Myth: A Very Short Introduction.'' Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0192803474. p.113</ref> |

Traditionally viewed by Jews (and still viewed that way by [[Orthodox Jews]]) as having been authored by [[God in Judaism|God]], it was later adopted by Christians as well. The Genesis creation narratives have had an exceptionally long and complex history of interpretation. Until the latter half of the 19th century, they were seen as one continuous, uniform story with {{Bibleref2|Genesis|1:1–2:3}} outlining the world's origin, and {{Bibleref2-nb|Genesis|2:4–2:25}} carefully painting a more detailed picture of the creation of humanity. However, recent scholarship opines that there are two unique accounts of creation, persuaded by the use of two different names for God the creator, two different emphases (physical vs. moral issues), and a different order of creation (plants before humans, plants after humans). Today, it is nearly universally accepted that Genesis contains two distinct creation narratives, written many years apart by two different sources, each of which experienced a distinct historical climate.<ref>Segal, Robert A. ''Myth: A Very Short Introduction.'' Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0192803474. p.113</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:43, 8 April 2010

Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled until July 26, 2025 at 16:43 UTC, or until editing disputes have been resolved. This protection is not an endorsement of the current version. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

The Genesis creation account[note 1][1] is the biblical account of the beginnings of the Earth, life, and humanity as described in the first two chapters of the Book of Genesis. It is considered a sacred narrative[2]: p.9 in Judaism, and Christianity, but not Islam, as the Quranic account of creation is substantially different.

Traditionally viewed by Jews (and still viewed that way by Orthodox Jews) as having been authored by God, it was later adopted by Christians as well. The Genesis creation narratives have had an exceptionally long and complex history of interpretation. Until the latter half of the 19th century, they were seen as one continuous, uniform story with Genesis 1:1–2:3 outlining the world's origin, and 2:4–2:25 carefully painting a more detailed picture of the creation of humanity. However, recent scholarship opines that there are two unique accounts of creation, persuaded by the use of two different names for God the creator, two different emphases (physical vs. moral issues), and a different order of creation (plants before humans, plants after humans). Today, it is nearly universally accepted that Genesis contains two distinct creation narratives, written many years apart by two different sources, each of which experienced a distinct historical climate.[3]

The first narrative, Genesis 1:1–2:3, begins with the indeterminate period in which God created the heavens and the earth out of nothing (ex nihilo)[4] or out of primordial waters / chaos.[5] Next it describes the transformation of creation in six "days" from chaos to a state of order that culminates with God's creation of two humans "in his own image." The seventh "day" is sanctified by God as a day of rest (Biblical Sabbath).

The second narrative in Genesis 2:4–2:25 follows a different sequence of creation. It tells of God planting a garden in which he forms the first man from dust, then creates the plants and animals and finally woman, and culminates in the sanctification of marriage.

The two narratives are linked by a short bridge and form part of a wider narrative unit labeled by some scholars as the Primeval History.[6]

Important theological ideas introduced in the two chapters include the concept of humanity being in the image of God (imago Dei) and the activity of the Spirit of God.[7]

Its genre has been variously described as a literal historical narrative account; as a mythic history in a symbolic representation of historical time; as ancient science as understood by the original authors; and as theology.[8]

Narratives

The modern division of Genesis into chapters dates from c. AD 1200, and the division into verses somewhat later; the distinction between Genesis 1 and 2 is therefore a relatively recent development.[9] Structurally, the division between two contrasting narratives Genesis 1:1–2:3 and Genesis 2:4–2:25 is of far more historical significance.[10]

Prologue

see main articles Ex nihilo and Chaos.

Genesis 1:1-2 has traditionally been seen as an indeterminate moment when God created space and time ex nihilo (out of nothing)[4] or out of primordial waters / chaos.[11][12][13]

Two common translations begin with "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth" (KJV) or the alternate "When God began to create the heavens and the earth" (TEV). Either the subject is the beginning of time (the first translation) or the beginning of creation (the second). The result is "without form and void."

This has been interpreted in at least two ways:[14]

- Verses 1 and 2 form the basis for all subsequent formation. Chaos is not the precursor of creation, as in Babylonian myths, but the result. The two subsequent narratives do not merely repeat or demythologize oriental creation myths, but use this to polemically repudiate them.[15]

- Verses 1 and 2 together summarize the entire first creation narrative, allowing the presupposition of 'the existence of matter, of raw material for God to use'.[13]

First narrative: Creation week

The remainder of the creation narrative more closely parallels the Mesopotamian accounts, detailing the formation of unique features out of a separation of waters, an understanding reflected even in the New Testament 2 Pet 3:4–7 in which it is understood that 'earth was formed out of water and by water'[16] Jungian mythologists, such as Joseph Campbell, find this creation out of water to be a possible holdover from neolithic matriarchal goddess religions, in which the universe is not created, but born (i.e., the water as amniotic fluid).[17]

The creation week narrative consists of eight divine commands executed over six days, followed by a seventh day of rest.

- First day: God creates light ("Let there be light!")Gen 1:3—the first divine command. The light is divided from the darkness, and "day" and "night" are named.

- Second day: God creates a firmament ("Let a firmament be...!")Gen 1:6–7—the second command—to divide the waters above from the waters below. The firmament is named "skies".

- Third day: God commands the waters below to be gathered together in one place, and dry land to appear (the third command).Gen 1:9–10 "Earth" and "sea" are named. God commands the earth to bring forth grass, plants, and fruit-bearing trees (the fourth command).

- Fourth day: God creates lights in the firmament (the fifth command)Gen 1:14–15 to separate light from darkness and to mark days, seasons and years. Two great lights are made (most likely the Sun and Moon, but not named), and the stars.

- Fifth day: God commands the sea to "teem with living creatures", and birds to fly across the heavens (sixth command)Gen 1:20–21 He creates birds and sea creatures, and commands them to be fruitful and multiply.

- Sixth day: God commands the land to bring forth living creatures (seventh command);Gen 1:24–25 He makes wild beasts, livestock and reptiles. He then creates humanity in His "image" and "likeness" (eighth command).Gen 1:26–28 They are told to "be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it." Humans and animals are given plants to eat. The totality of creation is described by God as "very good."

- Seventh day: God, having completed the heavens and the earth, rests from His work, and blesses and sanctifies the seventh day.

Literary Bridge

- These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created.

The phrase "These are the generations (Hebrew תוֹלְדוֹת; tôledôt) of the heavens and the earth when they were created" lies between the creation week account and the account of Eden which follows, and the first of ten phrases ("tôledôt") used to provide structure to the book of Genesis.[18] Since the phrase always precedes the "generation" to which it belongs, the "generations of the heavens and the earth" should logically be taken to refer to Genesis 2; a position taken by most commentators.[19] Nevertheless, other commentators from Rashi to the present day have argued that in this case it should apply to what precedes.[20]

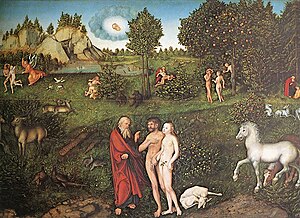

Second narrative: Eden

The second creation account in Genesis reflects a different historical and literary context.[21] Chronologically it was written after the experiences of the Babylonian exile. It is considered far more modern for its time than the polytheistic cosmogonies of Mesopotamia could have been, and introduces a far more restrictive use of the name Yahweh than the common use of the name in Amorite culture[22]. The second narrative represents a partial demythologizing of nature, interpreting both nature and myth differently. Its presentation uses imagery reflective of the pastoral tradition of Israel that is difficult to interpret today: the world of the shepherd.[23] The Eden narrative addresses the creation of the first man and woman:

- Genesis 2:4b—the second half of the bridge formed by the "generations" formula, and the beginning of the Eden narrative—places the events of the narrative "in the day when YHWH Elohim made the earth and the heavens...."[24]

- Before any plant had appeared, before any rain had fallen, while a mist[25] watered the earth, Yahweh formed the man (Heb. ha-adam הָאָדָם) out of dust from the ground (Heb. ha-adamah הָאֲדָמָה), and breathed the breath of life into his nostrils. And the man became a "living being" (Heb. nephesh).

- Yahweh planted a garden in Eden and he set the man in it. He caused pleasant trees to spout from the ground, and trees necessary for food, also the tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. Some modern translations alter the tense-sequence so that the garden is prepared before the man is set in it, but the Hebrew has the man created before the garden is planted. An unnamed river is described: it goes out from Eden to water the garden, after which it parts into four named streams. He takes the man who is to tend His garden and tells him he may eat of the fruit of all the trees except the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, "for in that day thou shalt surely die."

- Yahweh resolved to make a "helper"[26] suitable for (lit. "corresponding to")[27] the man.[28] He made domestic animals and birds, and the man gave them their names, but none of them is a fitting helper. Therefore, Yahweh caused the man to sleep, and he took a rib,[29] and from it formed a woman. The man then named her "Woman" (Heb. ishah), saying "for from a man (Heb. ish) has this been taken." A statement instituting marriage follows: "Therefore shall a man leave his father and his mother, and shall cleave unto his wife: and they shall be one flesh." The lack of punctuation in the Hebrew makes it uncertain whether or not these words about marriage are intended to be a continuation of the speech of the man.

- The man and his wife were naked, and felt no shame.

Genesis 1–11: Primeval History

Genesis 1–2 opens the “primeval history” of Genesis 1–11. This unit within Genesis forms an introduction to the stories of Abraham and the Patriarchs, and contains the first mention of many themes which are continued throughout the book of Genesis and the Torah, including fruitfulness, God's election of Israel, and His ongoing forgiveness of man's rebellious nature. It is therefore impossible to understand either Genesis 1–2 or the Torah as a whole without reference to this introductory history.[30]

Other Biblical creation narratives

Elsewhere in the Bible there are other accounts of creation. "Divine struggle with waters, victory over chaos, and cosmogonic promulgation of law/wisdom are found throughout biblical poetry (cf. Isaiah 40–42; Hebrews 3 and 8; Psalms 18, 19, 24; 24; 33; 68; 93; 95; 104; Proverbs 8:22–33; Job 38–41 ..."[31]

Ancient Near East context

The worldview which lies behind the Genesis creation story is that of the common cosmology of the Ancient Near East:[32] To civilizations of the Ancient Near East, the Earth was conceived as a flat disk with infinite water both above and below. The dome of the sky was thought to be a solid metal bowl (tin according to the Sumerians, iron for the Egyptians) separating the surrounding water from the habitable world. The stars were embedded in the lower surface of this dome, with gates that allowed the passage of the Sun and Moon back and forth. The flat-disk Earth was seen as a single island-continent surrounded by a circular ocean, of which the known seas—what we call today the Mediterranean Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea—were inlets. Beneath the Earth was a fresh-water sea, the source of all fresh-water rivers and wells.[32]

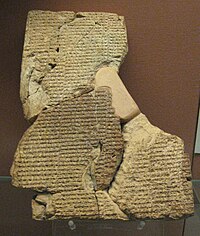

The two Genesis creation narratives—Genesis 1:1–2:3 and Genesis 2:4–2:25—are both comparable with other Near Eastern creation myths—notably Narrative I has close parallels with the Enûma Eliš[33][34] and Narrative II has parallels with the Atra-Hasis[35]

According to the Enûma Eliš the original state of the universe was a chaos formed by the mingling of two primeval waters, the female saltwater Tiamat and the male freshwater Apsu.[36] The opening six lines read:

- When skies above were not yet named

- Nor earth below pronounced by name

- Apsu, the first one, their begetter

- And maker Tiamat, who bore them all

- Had mixed their waters together,

- But had not formed pastures, nor discovered reed-beds[37]

Through the fusion of their waters six successive generations of gods were born. A war amongst the gods began with the slaying of Apsu, and ended with the god Marduk splitting Tiamat in two to form the heavens and the earth; the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers emerged from her eye-sockets. Marduk then created humanity, from clay mingled with spit and blood, to tend the Earth for the gods, while Marduk himself was enthroned in Babylon in the Esagila, "the temple with its head in heaven."

Adapa (cognate with Adam) was a Babylonian mythical figure who unknowingly refused the gift of immortality. The story[38] is first attested in the Kassite period (14th century BC). Mario Liverani[39] points to multiple parallels between the story of Adapa, who obtains wisdom but who is forbidden the 'food of immortality' whilst in heaven, and the story of Adam in Eden.

Ningishzida was a Mesopotamian serpent deity associated with the underworld. He was often depicted protectively wrapped around a tree as a guardian. Thorkild Jacobsen interprets his name in Sumerian to mean "lord of the good tree"[40]

Despite apparent similarities between Genesis and the Enûma Eliš, there are also significant differences. The most notable is the absence from Genesis of the "divine combat" (the gods' battle with Tiamat) which secures Marduk's position as king of the world, but even this has an echo in the claims of Yahweh's kingship over creation in such places as Psalm 29 and Psalm 93, where he is pictured as sitting enthroned over the floods[36] and Isaiah 27:1"In that day, the Lord will punish with his sword; his fierce, great and powerful sword; Leviathan the gliding serpent, Leviathan the coiling serpent; he will slay the monster of the sea." Thus this creation account may be seen as either a borrowing or historicizing of Babylonian myth[41] or, in contrast, may be seen as a repudiation of Babylonian ideas about origins and humanity.[42]

Structure and composition

Structure

Genesis 1 consists of an indeterminate time period that God created space and time ex nihilo (out of nothing)[4] followed by eight acts of creation within a six day framework. During the indeterminate time period described in verses 1 and 2 there is no division in time. In each of the first three days there is an act of division: Day one divides the darkness from light; day two, the waters from the skies; and day three, the sea from the land. In each of the next three days these divisions are populated: day four populates what was created on day one, and heavenly bodies are placed in the darkness and light; day five populates what was created on day two, and fish and birds are placed in the seas and skies; finally, day six populates what was created on day three, and animals and man are place on the land. This six-day structure is symmetrically bracketed: On day zero primeval chaos reigns, and on day seven there is cosmic order.[43]

Genesis 2 is a simple linear narrative, with the exception of the parenthesis about the four rivers at 2:10–14. This interrupts the forward movement of the narrative and is possibly a later insertion.[44]

The two are joined by Genesis 2:4a, "These are the tôledôt (תוֹלְדוֹת in Hebrew) of the heavens and the earth when they were created." This echoes the first line of Genesis 1, "In the beginning Elohim created both the heavens and the earth," and is reversed in the next line of Genesis 2, "In the day when Yahweh Elohim made the earth and the heavens...". The significance of this, if any, is unclear, but it does reflect the preoccupation of each chapter, Genesis 1 looking down from heaven, Genesis 2 looking up from the earth.[45]

Composition

Today most scholars accept that the Pentateuch is "a composite work, the product of many hands and periods.”[46] Genesis 1 and 2 are seen as the products of two separate authors, or schools: Genesis 1 is by an author, or school of authors, called the P (for Priestly), while Genesis 2 is by a different author or or group of authors called J (for Jahwist - sometimes called non-P). There are several competing theories as to when and how these two chapters originated - some scholars believe they each come from two originally complete but separate narratives spanning the entire Biblical story from Creation to the death of Moses, while others believe that J is not a complete narrative but rather a series of edits of the J material, which itself was not a single document so much as a collection of material. In either case, it is generally agreed that the J account (Genesis 2) is older than P (Genesis 1), that both were written during the 1st millenium BC, and that they reached the combined form in which we know them today about 450 BC.

Exegetical points

Template:Mesopotamian myth (primordial)

Creation myth

In academics, the Genesis creation narrative is often described as a "creation myth" or cosmogonic myth. From its Greek origin, myth is simply defined as a story or legend that has cultural significance in explaining the how's and why's of human existence, using metaphorical language to express ideas beyond the realm of our five senses. It refers to a culture's theory of its origins─a supernatural story or explanation that describes the beginnings of humanity, earth, life, and the universe, as viewed by that culture or religious group. It does not imply made up works of the imagination.[47]

In its popular definition "myth" has become synonymous with "not true".[47] Theologian N.T. Wright, while defending the technical designation of the Genesis creation accounts as mythical, explains that the characterization of Genesis 1-3 as a “mythic” text is offensive to many Christians and Jews who consider their Bible to contain "sacred text." But to suggest that Genesis is both a mythic text as well as the "inerrant Word of God" may require a leap of faith for some, he says. The popular "not true" conceptualization of myth, even if disclaimed by an author, is seen as negatively affecting the reputation of the validity of scripture, historically considered by both Jews and Christians to be the revelation of God.

Biblical scholars exegete incidents in Genesis and other Hebrew Bible passages as containing prefigurations (prototypes) of cardinal New Testament concepts, including the Passion of Christ and the Eucharist.[48]

A non-literal and non-historical reading of Genesis has negative implications for an evangelical understanding of the New Testament. This is largely because the New Testament, for example in Matthew 19:4, also refers to Adam and Eve as literal historical characters. A primary reason for fundamentalist opposition to the whole idea of evolution is a literalist reading of scripture—especially the text detailing the creation of the earth and its inhabitants in Genesis 1–3.[47]

The issue for Christians is a dual hermeneutical issue: how do we understand Genesis in a way that is in honest conversation with what we know today scientifically and in terms of ancient Near Eastern religious texts that parallel Genesis? Then, how do we handle Paul's understanding of Genesis when he was not aware of the very factors that force our own reconsideration of Genesis. Evangelicalism is not well equipped to address this issue because of its polemical history, some of which N.T. Wright alludes to.[47] To both Jews and Christians, the creation account provides an introduction to the Sinai covenant─information that makes the author's view of the Sinai covenant understandable.[49]

Wright suggests that the mythological part has been misunderstood and discarded by many evangelicals in favor of a reading based entirely on questions of historicity. Wright suggests that questions concerning the historicity of Genesis and the historicity of Adam and Eve get caught up in contemporary cultural issues and miss the larger story. He argues that...

...to flatten that [the text of Genesis] out is to almost perversely avoid the real thrust of the narrative … we have to read Genesis for all it's worth and to say either history or myth is a way of saying 'I’m not going to read this text for all its worth, I am just going to flatten it out so that it conforms to the cultural questions that my culture today is telling me to ask'.[47]

"In the beginning..."

The first word of Genesis 1 in Hebrew, "in the beginning" (Heb. berēšît בְּרֵאשִׁית), provides the traditional Jewish title for the book. The inherent ambiguity of the Hebrew grammar in this verse gives rise to two alternative translations, the first implying that God's initial act of creation was before time was created and ex nihilo (out of nothing),[4][50] the second that "the heavens and the earth" (i.e., everything) already existed in a "formless and empty" state, to which God brings form and order:[51]

- "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void…. God said, Let there be light!" (King James Version).

- "At the beginning of the creation of heaven and earth, when the earth was (or the earth being) unformed and void.... God said, Let there be light!" (Rashi, and with variations Ibn Ezra and Bereshith Rabba).

The Names of God

Two names of God are used, Elohim in the first account and Yahweh Elohim in the second account. In Jewish tradition, dating back to the earliest rabbinic literature, the different names indicate different attributes of God.[52][53] In modern times the two names, plus differences in the styles of the two chapters and a number of discrepancies between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2, were instrumental in the development of source criticism and the documentary hypothesis.

"Without form and void"

The phrase traditionally translated in English "without form and void" is tōhû wābōhû (Hebrew: תֹהוּ וָבֹהוּ). The Greek Septuagint (LXX) rendered this term as "unseen and unformed" (Greek: ἀόρατος καὶ ἀκατασκεύαστος), paralleling the Greek concept of Chaos. In the Hebrew Bible, the phrase is a dis legomenon, being used only in one other place.Jer. 4:23 There Jeremiah is telling Israel that sin and rebellion against God will lead to "darkness and chaos," or to "de-creation," "as if the earth had been ‘uncreated.’"[54]

The rûach of God

The Hebrew rûach (רוּחַ) has the meanings "wind, spirit, breath," but the traditional Jewish interpretation here is "wind," as "spirit" would imply a living supernatural presence co-extent with yet separate from God at Creation. This, however, is the sense in which rûach was understood by the early Christian church in developing the doctrine of the Trinity, in which this passage plays a central role.[51]

The "deep"

The "deep" (Heb. תְהוֹם tehôm), is the formless body of primeval water surrounding the habitable world. These waters are later released during the great flood, when "all the fountains of the great deep burst forth" from under the earth and from the "windows" of the sky.Gen. 7:11 [19] The word itself may show literary or linguistic parallels with the Babylonian Tiawath (chaos) or the Assyrian Tamtu (deep sea).[55] Gunkel accused the conservative Christian scholar, Gordon Wenham to accept that tehôm is cognate with the Babylonian Tiamat,[19] believing its occurrence here without the definite article ha (i.e., the literal translation of the Hebrew is that "darkness lay on the face of tehôm) indicates its mythical origins.[56] However, Wenham himself writes that "there is no hint in the biblical text that the deep was a power, independent of God, which he had to fight to control. Rather is it part of his creation that does his bidding.[57]

Wenham goes on to respond to Gunkel and summarize a number of views:

Gunkel suggested that Hebrew t'hom was to be identified with Tiamat, the Babylonian goddess, slain by Marduk, whose carcass was used to create heaven and earth. He saw in Gen 1:2 an allusion to the Mesopotamian creation myths. Though Otzen (Myths in the OT, 33-34) has reaffirmed this connection, Heidel (Babylonian Genesis, 98-101) showed that a direct borrowing is impossible. Both Hebrew and Babylonian Ti'amat are independently derived from a common Semitic root. Westermann justly states that the OT usage of t'hom "does not allow us to speak of a demythologizing of a mythical idea or name as do many commentaries, When P inherited the word t'hom, it had long been used to describe a flood of waters without any mythical echo" (1:105). That is not to say that this verse shows no connection with other oriental concepts of creation. In ancient cosmogonies a reference to a primeval flood is commonplace (Westermann, 1:105-6). But the word t'hom is not an allusion to the conquest of Tiamat as in the Babylonian myth.

Further, David Tsumura has demonstrated, from standard linguistic methodology, that it is impossible to derive tehôm from Tiamat directly.[58]

Tehom cannot linguistically derive from Tiamat since the second consonant of Ti’amat, which is the laryngeal alef, disappears in Akkadian in the intervocalic position and would not be manufactured as a borrowed word. This occurs, for instance, in the Akkadian Ba'al which becomes Bel. ... Tiamat and tehom must come from a common Semitic root *thm. The same root is the base for the Babylonian tamtu and also appears as the Arabic tihamatu or tihama, a name applied to the coastline of Western Arabia, and the Ugaritic t-h-m which means "ocean" or "abyss." The root simply refers to deep waters. [59]

The firmament of heaven

The "firmament" (Heb. רָקִיעַ rāqîa) of heaven, created on the second day of creation and populated by luminaries on the fourth day, denotes a solid ceiling[32] which separated the earth below from the heavens and their waters above. The term is etymologically derived from the verb rāqa (רֹקַע ), used for the act of beating metal into thin plates.[19][60]

Great sea monsters

Heb. hatanninim hagedolim (הַתַּנִּינִם הַגְּדֹלִים) is the classification of creatures to which the chaos-monsters Leviathan and Rahab belong.[61] In Genesis 1:21, the proper noun Leviathan is missing and only the class noun great tannînim appears. The great tannînim are associated with mythological sea creatures such as Lotan (the Ugaritic counterpart of the biblical Leviathan) which were considered deities by other ancient near eastern cultures; the author of Genesis 1 asserts the sovereignty of Elohim over such entities.[60]

The number seven

Seven denoted divine completion.[62] It is embedded in the text of Genesis 1 (but not in Genesis 2) in a number of ways, besides the obvious seven-day framework: the word "God" occurs 35 times (7 × 5) and "earth" 21 times (7 × 3). The phrases "and it was so" and "God saw that it was good" occur 7 times each. The first sentence of Genesis 1:1 contains 7 Hebrew words comprised of 28 Hebrew letters (7 × 4), and the second sentence contains 14 words (7 × 2), while the verses about the seventh dayGen. 2:1–3 contain 35 words (7 × 5) in total.[63]

Man and the image of God

The meaning of the "image of God" has been much debated. The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria and the medieval Jewish scholar Rashi believed it referred to "a sort of conceptual archetype, model, or blueprint that God had previously made for man;" his colleague Maimonides suggested it referred to man's free will.[64] Modern scholarship still debates whether the image of God was represented symmetrically in Adam and Eve, or whether Adam possessed the image more fully than the woman.

Theology and Judaeo-Christian interpretation

Questions of genre

The genre of Genesis 1–2 (and Genesis 1–11, the larger whole to which the two chapters belong) remains subject to differences of opinion, and modern scholars can only make informed judgments. One inevitable conclusion is that Genesis 1–2 represent theology: the chapters concern the actions of God and the meaning of those acts. The story is also presented with a clear chronological progression as part of a history that leads from the moment of first creation to the destruction of the First Temple, leading mythologist Thorkild Jacobsen to classify it as "mythical history".[65]

It has been variously described as historical narrative[66][67] (i.e., a literal account); as mythic history (i.e., a symbolic representation of historical time); as ancient science (in that, for the original authors, the narrative represented the current state of knowledge about the cosmos and its origin and purpose); and as theology (as it describes the origin of the Earth and humanity in terms of God).[8]

Prologue: In the Beginning

In the first two verses of Genesis some Biblical scholars, commentators, and theologians within the Judaeo-Christian tradition such as Philo[68] [69], Augustine[70], John Calvin[71], John Wesley[72], Matthew Henry [73] believe that pre-creation is being described. Philo postulates that the origins of the universe stem from the ideas of God which eventually are used as the pattern for the creation of the material universe described in the later verses. The creation of material objects starts with the idea of the object and then the idea is transformed into reality.

For God, as apprehending beforehand, as a God must do, that there could not exist a good imitation without a good model, and that of the things perceptible to the external senses nothing could be faultless which was not fashioned with reference to some archetypal idea conceived by the intellect, when he had determined to create this visible world, previously formed that one which is perceptible only by the intellect, in order that so using an incorporeal model formed as far as possible on the image of God, he might then make this corporeal world, a younger likeness of the elder creation, which should embrace as many different genera perceptible to the external senses, as the other world contains of those which are visible only to the intellect.

— Philo—On the Creation (16)

Philo also notes that time is a result of space (universe/world) and that God created space which resulted in time also being created either simultaneously with space or immediately thereafter.[74] See main article spacetime.

Theology of Genesis 1–2

Jewish and Christian theology both define God as unchangeable since he created time and therefore transcends time and is not affected by it.[75][76][77]

Traditional Jewish scholarship has viewed it as expressing spiritual concepts (see Nachmanides, commentary on Genesis). The Mishnah in Tractate Chagigah states that the actual meaning of the creation account, mystical in nature and hinted at in the text of Genesis, was to be taught only to advanced students one-on-one. Tractate Sanhedrin states that Genesis describes all mankind as being descended from a single individual in order to teach certain lessons. Among these are:

- Taking one life is tantamount to destroying the entire world, and saving one life is tantamount to saving the entire world.

- A person should not say to another that he comes from better stock because we all come from the same ancestor.

- To teach the greatness of God, for when human beings create a mold every thing that comes out of that mold is identical, while mankind, which comes out of a single mold, is different in that every person is unique.[78]

Among the many views of modern scholars on Genesis and creation one of the most influential is that which links it to the emergence of Hebrew monotheism from the common Mesopotamian/Levantine background of polytheistic religion and myth around the middle of the 1st millennium BC.[79] The "Creation week" narrative forms a monotheistic polemic on creation-theology directed against gentile creation myths, the sequence of events building to the establishment of the Biblical Sabbath (in Hebrew: שַׁבָּת, Shabbat) commandment as its climax.[80] Where the Babylonian myths saw man as nothing more than a "lackey of the gods to keep them supplied with food,"[81] Genesis starts out with God approving the world as "very good" and with mankind at the apex of created order.Gen. 1:31 Things then fall away from this initial state of goodness: Adam and Eve eat the fruit of the tree in disobedience of the divine command. Ten generations later in the time of Noah, the Earth has become so corrupted that God resolves to return it to the waters of chaos sparing only one man who is righteous and from whom a new creation can begin.

Creationism

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Creationism | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| History | ||||

| Types | ||||

| Biblical cosmology | ||||

| Creation science | ||||

| Rejection of evolution by religious groups | ||||

| Religious views | ||||

|

||||

The ideology of creationism springs from the belief that if one element of the biblical narrative is shown to be untrue, then all others will follow: "Tamper with the Book of Genesis and you undermine the very foundations of Christianity.... If Genesis 1 is not accurate, then there's no way to be certain that the rest of Scripture tells the truth."[82] Thus a literal genre, Genesis as history, is substituted for the symbolic Genesis as theology, and the text is placed in conflict with science.[83] "Young Earth" creationists believe that the seven "days" of Genesis 1 correspond to normal 24-hour days while Day-age creationists, more willing to adjust their religious beliefs to accommodate current scientific findings, hold that each "day" represents an "age" of perhaps millions or even billions of years. Creationists read Genesis 2 as history, holding that God breathed into the nostrils of a being formed out of dust, and from his side (or rib) the first woman was formed.[84]

See also

- Allegorical interpretations of Genesis

- Babylonian mythology

- Biblical criticism

- Christian mythology

- Hexameron

- Jewish mythology

- Mesopotamian mythology

- Religion and mythology

- Sacred history

- Sumerian creation myth

- Sumerian literature

- Tree of life

- Timeline of the Bible

Notes

Cite error: A list-defined reference named "myth" is not used in the content (see the help page).

References

- ^ Browning, W. R. F. (1997). A Dictionary of the Bible (myth). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192116918.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Dundes, Alan. Sacred Narrative: Readings in the Theory of Myth. University of California Press, 1984. ISBN-13: 978-0520051928

- ^ Segal, Robert A. Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0192803474. p.113

- ^ a b c d See:

- Douglas 1956

- Smoot & Davidson 1993, pp. 30, 189

- Herbert 1985, p. 177

- Parker 1988, p. 202

- Fain 2007, pp. 30–36

- Heeren 2000, pp. 107–108, 121, 135, 157

- Schaff 1995

- Clontz 2008

- Jastrow 1992, p. 14

- Ellis 1993, p. 97

- Yonge 1993

- ^ Bauckham, Richard Word Biblical Commentary: Jude, 2 Peter Paternoster (1 Jan 2001) ISBN 0849902495 (p297)

- ^ Rendtorff, Rolf. Problem of the Process of Transmission in the Pentateuch. (Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies) Sheffield Academic Press, 2009. ISBN 0567187926

- ^ or wind (Hebrew ruach—רוּחַ rûaħ

- ^ a b Sparks, Kenton. God's Word in Human Words: An Evangelical Appropriation of Critical Biblical Scholarship. Baker Academic, 2008. ISBN 0801027012 (see Chapters 6 & 7 on Biblical Genres)

- ^ Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: Volume 1, The Pentateuch", SPCK, (2003), p.5.

- ^ Documentary Hypothesis (notes from John Barton, "Source Criticism," Anchor Bible Dictionary) describes both the documentary hypothesis and the Mosaic authorship tradition.

- ^ Bauckham, Richard Word Biblical Commentary: Jude, 2 Peter Paternoster (1 Jan 2001) ISBN 0849902495 (p297): 'According to the creation account in Gen 1, and in accordance with general Near Eastern myth, the world—sky and earth—merged out of a primeval ocean (Gen 1:2, 6–7, 9; cf. Ps 33:7; 136:6; Prov 8:27–29; Sir 39:17; Herm. Vis. 1:3:4). The world exists because the waters of chaos, which are now above the firmament, beneath the earth and surrounding the earth, are held back and can no longer engulf the world. The phrase ἐξ ὕδατος ("out of water") expresses this mythological concept of the world's emergence out of the watery chaos, rather than the more "scientific" notion, taught by Thales of Miletus, that water is the basic element out of which everything else is made (cf. Clem. Hom. 11:24:1)'

- ^ Yonge 1993

- ^ a b Goldinghay, John Old Testament Theology: Israel's Gospel v.1 Paternoster Press (19 Jan 2007) ISBN 1842274961

- ^ Gordon Wenham, Genesis: Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 1, pp. 11-12. Wenham actually gives three variations of this second view, although he adopts the view of creation ex nihilo in his commentary and translation. The four views Wenham gives are:

- "V1 is a temporal clause subordinate to the main clause in v 2...

- V1 is a temporal clause subordinate to the main clause in v 3...

- V1 is a main clause, summarizing all the events described in vv 2-31...

- V1 is a main clause describing the first act of creation. Vv 2 and 3 describe subsequent phases in God's creative activity. This is the traditional view adopted in our translation."

- ^ Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 1, pp. 9

- ^ —Bauckham, Richard Word Biblical Commentary: Jude, 2 Peter Paternoster (1 Jan 2001) ISBN 0849902495 (p297): 'According to the creation account in Gen 1, and in accordance with general Near Eastern myth, the world—sky and earth—merged out of a primeval ocean (Gen 1:2, 6–7, 9; cf. Ps 33:7; 136:6; Prov 8:27–29; Sir 39:17; Herm. Vis. 1:3:4). The world exists because the waters of chaos, which are now above the firmament, beneath the earth and surrounding the earth, are held back and can no longer engulf the world. The phrase ἐξ ὕδατος ("out of water") expresses this mythological concept of the world's emergence out of the watery chaos, rather than the more "scientific" notion, taught by Thales of Miletus, that water is the basic element out of which everything else is made (cf. Clem. Hom. 11:24:1)'

- ^ Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth, disc 1 of 6.

- ^ Frank Moore Cross, "The Priestly Work," in Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic, 1973. The other nine are for 2 Adam [1],Genesis 5:1 3 Noah,Genesis 6:9 4 Noah's sons Genesis 10L1, 5 Shem,Gen. 11:10 6 Terah,Gen. 11:27 7 Yishmael,Gen. 25:12 8 Isaac,Gen. 25:19 9 Esau,Gen. 36:1 and 10 Jacob.Gen. 37:2

- ^ a b c d Gordon J. Wenham. Genesis 1–15 (Word Biblical Commentary). Word Books, Texas, 1987.

- ^ The argument is based on several grounds, notably the fact that Genesis 1 uses the phrase "heavens and earth" to introduce and close the Creation, while the account in Chapter 2 is introduced by the phrase "earth and heavens." Advocates of the other view argue that 2:4 is designed as a chiasm (Wenham, 49)

- ^ Hyers, Conrad (1984). Meaning of Creation: Genesis and Modern Science. p. 107.

- ^ Peter Watson, Ideas: A History (folio edition), Volume 1 of 4, page 108 (citing H.W.F. Saggs, Before Greece and Rome, page 107)

- ^ Hyers, Conrad (1984). The Meaning of Creation: Genesis and Modern Science. p. 107.

- ^ The lack of punctuation in the Hebrew creates ambiguity over where sentence-endings should be placed in this passage. This is reflected in differing modern translations, some of which attach this clause to Genesis 2:4a and place a full stop at the end of 4b, while others place the full stop after 4a and make 4b the beginning of a new sentence, while yet others combine all verses from 4a onwards into a single sentence culminating in Genesis 2:7.

- ^ in some translations, a stream

- ^ `ezer: Most often used to refer to God, such as "The Lord is our Help (`ezer)"Ps. 115:9 and many other Old Testament verses. (Strong's H5828)

- ^ footnote to Gen. 2:18 in NASB

- ^ Kvam, Kristen E., Linda S. Schearing, Valarie H. Ziegler, eds. Eve and Adam: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim readings on Genesis and gender. Indiana University Press, 1999. ISBN 0253212715.

- ^ Hebrew tsela`, meaning side, chamber, rib, or beam (Strong's H6763). Some scholars have questioned the traditional "rib" on the grounds that it denigrates the equality of the sexes, suggesting it should read "side": see Reisenberger, Azila Talit. "The creation of Adam...." in Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought, 9/22/1993 (accessed 09–12–2007).

- ^ For a schematic representation of the structure of the "primeval history", see table iii of this document from McMaster University (table i contains a breakdown of the "history"according to the documentary hypothesis); for a more detailed discussion, see "Pentateuchal Research", Encyclopedia of Christianity (somewhat dated, but scholarly).

- ^ entry creation, page 193, in Harper's Bible Dictionary, general editor Paul J. Achtemeier, San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985, ISBN 0-06-069862-4

- ^ a b c For a description of Near Eastern and other ancient cosmologies and their connections with the Biblical view of the Universe, see Paul H. Seeley, "The Firmament and the Water Above: The Meaning of Raqia in Genesis 1:6–8", Westminster Theological Journal 53 (1991), and "The Geographical Meaning of 'Earth' and 'Seas' in Genesis 1:10", Westminster Theological Journal 59 (1997).

- ^ Heidel, Alexander. Babylonian Genesis Chicago University Press; 2nd edition edition (1 Sep 1963) ISBN 0226323994 (See especially Ch3 on Old Testament Parallels)

- ^ Smith, Mark S. The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts Oxford University Press USA (30 Aug 2001) ISBN 019513480X (See especially Ch 9.1)

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and others Oxford World Classics, Oxford University Press (2000) ISBN 0192835890 (see esp. p.4 Atrahasis Introduction on 'Creation of Man')

- ^ a b Bandstra, Barry L. (1999), "Enûma Eliš", Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and others. Oxford World Classics, Oxford University Press (2000) ISBN 0192835890 (p233 The Epic of Creation. Tablet 1.) [2]

- ^ Adapa: Babylonian mythical figure

- ^ Liverani, Mario. Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Cornell University Press (August 30, 2007) (Ch1 Adapa, guest of the Gods pp.21-23) [3]

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild The Treasures of Darkness: History of Mesopotamian Religion Yale University Press; New edition edition (1 July 1978) ISBN 0300022913 (page 7)

- ^ Heidel, Alexander Babylonian Genesis Chicago University Press; 2nd edition edition (1 Sep 1963) ISBN 0226323994; Smith, Mark S. The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel William B Eerdmans Publishing Co; 2nd edition (18 Oct 2002) ISBN 080283972X; Smith, Mark S. The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts Oxford University Press USA; New Ed edition (27 Nov 2003) ISBN 0195167686; Frank Moore Cross 'Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel' Harvard University Press; New edition edition (29 Aug 1997) ISBN 0674091760]

- ^ K. A. Mathews, vol. 1A, Genesis 1-11:26, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2001), p. 89.

- ^ Bandstra, Barry L. (1999), "Priestly Creation Story", Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- ^ David Carr, “The Politics of Textual Subversion: A Diachronic Perspective on the Garden of Eden Story”, Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 112, No. 4 (Winter, 1993), pp. 577–595.

- ^ Richard Elliott Friedman, "The Bible With Sources Revealed", (Harper San Francisco, 2003), fn 3, p. 35

- ^ Speiser, E. A. (1964). Genesis. The Anchor Bible. Doubleday. p. XXI. ISBN 0-385-00854-6.

- ^ a b c d e Wright, N.T. Meaning and Myth. The BioLogos Foundation » Science & the Sacred. Web: 1 Mar 2020. Meaning and Myth.

- ^ Janzen, David. The social meanings of sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible: a study of four writings. Walter de Gruyter Publisher, 2004. ISBN 978-3110181586

- ^ Sailhamer, John. "Exegetical Notes─Genesis 1:1-2:4a." Trinity Journal. Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. 5 NS (1984) 73-82. Web: 3 Mar 2010. Exegetical Notes─Genesis 1:1-2:4a

- ^ Wenham, Gordon. Word Biblical Commentary Vol. 1 Genesis 1–15. Word, 1987. ISBN 0849902002

- ^ a b Harry Orlinsky, Notes on Genesis, NJPS translation of the Torah

- ^ "Hashem/Elokim: Mixing Mercy with Justice" in The Aryeh Kaplan Reader [4]

- ^ The seventy faces of Torah: the Jewish way of reading the Sacred Scriptures, by Stephen M. Wylen [5]

- ^ H.B. Huey, vol. 16, Jeremiah, Lamentations, "The New American Commentary" (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2001, c1993), p. 85; Holladay, Jeremiah 1, p. 164; Thompson writes, "it's as if the earth had been ‘uncreated.’", Thompson, Jeremiah, NICOT, p. 230;

- ^ Lewis Spence, Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria (Easton Press edition), page 72

- ^ Noted by Hermann Gunkel—see Ernest Nicholson, "The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century", 2002, p.34.)

- ^ Gordon Wenham, Genesis: The Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 1, page 16

- ^ Tsumura (2005)

- ^ Roberto Ouro, "The Earth of Genesis 1:2: abiotic or chaotic?", Andrews University Seminary Studies 37 (1999): 39–53.

- ^ a b Victor P. Hamilton. The Book of Genesis (New International Commentary on the Old Testament). William B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, 1990.

- ^ Vocabulary of Biblical Hebrew, Texas A&M University.

- ^ Meir Bar-Ilan, The Numerology of Genesis (Association for Jewish Astrology and Numerology, 2003)

- ^ Gordon Wenham, Genesis 1–15 (Commentary, Word Books, 1987. p. 6

- ^ Footnotes to Genesis translation at bible.ort.org

- ^ Thorkild Jacobsen, "The Eridu Genesis", (JBL 100, 1981), pp.513–29

- ^ Feinberg, John S. (2006). "The Doctrine of Creation—Literary Genre of Genesis 1 and 2". No One Like Him: The Doctrine of God. Foundations of Evangelical Theology. Vol. 2. Good News Publishers. p. 577. ISBN 1581348118.

- ^ Boyd, Steven W. (2008). "The Genre of Genesis 1:1-2:3:What Means This Text?". In Terry Mortenson, Thane H Ury (ed.). Coming to Grips with Genesis: Biblical Authority and the Age of the Earth. New Leaf Publishing Group. pp. 174 ff. ISBN 0890515484.

- ^ Yonge, Charles Duke (1854). "Appendices A Treatise Concerning the World (1), On the Creation (16-19, 26-30), Special Laws IV (187), On the Unchangeableness of God (23-32)". The Works of Philo Judaeus: the contemporary of Josephus. London: H. G. Bohn. http://cornerstonepublications.org/Philo.

- ^ Clontz, T.E. and J. (2008). "The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh. Cornerstone Publications. ISBN 978-0-977873-71-5. (p. 473 Philo[Special Laws IV (187) cf. {Genesis 1:1-31}]; p. 494 Philo[Appendices A Treatise Concerning the World (1) cf. {Genesis 1:1, Deuteronomy 10:17})

- ^ The Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers First Series, Volume 1 The Confessions and Letters of Augustine with a Sketch of his Life and Work, 1896, Philip Schaff, Augustine Confessions - Book XI.11-30, XII.7-9

- ^ Commentaries on The First Book of Moses Called Genesis, by John Calvin, Translated from the Original Latin, and Compared with the French Edition, by the Rev. John King, M.A, 1578, Volume 1, Genesis 1:1-31 see http://www.ccel.org/ccel/calvin/calcom01.vii.i.html - “In the beginning. To expound the term “beginning,” of Christ, is altogether frivolous. For Moses simply intends to assert that the world was not perfected at its very commencement, in the manner in which it is now seen, but that it was created an empty chaos of heaven and earth. His language therefore may be thus explained. When God in the beginning created the heaven and the earth, the earth was empty and waste. He moreover teaches by the word “created,” that what before did not exist was now made; for he has not used the term יצר, (yatsar,) which signifies to frame or forms but ברא, (bara,) which signifies to create. Therefore his meaning is, that the world was made out of nothing. Hence the folly of those is refuted who imagine that unformed matter existed from eternity; and who gather nothing else from the narration of Moses than that the world was furnished with new ornaments, and received a form of which it was before destitute.”

- ^ John Wesley’s notes on the whole Bible the Old Testament, Notes On The First Book Of Moses Called Genesis, by John Wesley, p.14 see http://www.ccel.org/ccel/wesley/notes.ii.ii.ii.i.html - “Observe the manner how this work was effected; God created, that is, made it out of nothing. There was not any pre-existent matter out of which the world was produced. The fish and fowl were indeed produced out of the waters, and the beasts and man out of the earth; but that earth and those waters were made out of nothing. Observe when this work was produced; In the beginning — That is, in the beginning of time. Time began with the production of those beings that are measured by time. Before the beginning of time there was none but that Infinite Being that inhabits eternity.”

- ^ Matthew Henry’s Commentary on the Whole Bible, Unabridged, Genesis to Deuteronomy, by Matthew Henry see http://www.ccel.org/ccel/henry/mhc1.Gen.ii.html - “The manner in which this work was effected: God created it, that is, made it out of nothing. There was not any pre-existent matter out of which the world was produced. The fish and fowl were indeed produced out of the waters and the beasts and man out of the earth; but that earth and those waters were made out of nothing. By the ordinary power of nature, it is impossible that any thing should be made out of nothing; no artificer can work, unless he has something to work on.

- ^ Yonge 1993

- ^ Clontz 2008

- ^ Jastrow 1992, p. 14

- ^ Schaff 1995

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin 37a.

- ^ For a discussion of the roots of Biblical monotheism in Canaanite polytheism, see Mark S. Smith, "The Origins of Biblical Monotheism"; See also the review of David Penchansky, "Twilight of the Gods: Polytheism in the Hebrew Bible", which describes some of the nuances underlying the subject. See the Bibliography section at the foot of this article for further reading on this subject.

- ^ Meredith G. Kline, "Because It Had Not Rained", (Westminster Theological Journal, 20 (2), May 1958), pp. 146–57; Meredith G. Kline, "Space and Time in the Genesis Cosmogony", Perspectives on Science & Christian Faith (48), 1996), pp. 2–15; Henri Blocher, Henri Blocher. In the Beginning: The Opening Chapters of Genesis. InterVarsity Press, 1984.; and with antecedents in St. Augustine of Hippo Davis A. Young (1988). "The Contemporary Relevance of Augustine's View of Creation". Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith. 40 (1): 42–45.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|Format=|Format=ignored (|format=suggested) (help) - ^ T. Jacobson, "The Eridu Genesis", JBL 100, 1981, pp.529, quoted in Gordon Wenham, "Exploring the Old Testament: The Pentateuch", 2003, p.17. See also Gordon J. Wenham. Genesis 1–15 (Word Biblical Commentary). Word Books, Texas, 1987.

- ^ Literalist minister/theologian John MacArthur, in Eugenie C. Scott, "Evolution vs Creationism: An Introduction", University of California Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0520246508, pp. 227–8

- ^ Conrad Hyers, "The Meaning of Creation: Genesis and Modern Science", 1984, p. 75

- ^ Answers in Genesis—What Was Adam Like?

Bibliography

- Anderson, Bernhard W. (1997). Creation Ver Bernhard W. Understanding the Old Testament. ISBN 0-13-948399-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Anderson, Bernhard W. (1985). Creation in the Old Testament. ISBN 0-8006-1768-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Benware, P.N. (1993). Survey of the Old Testament. Moody Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blocher, Henri AG (1984). In the Beginning: the opening chapters of Genesis. InterVarsity Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bloom, Harold and Rosenberg (1990). David The Book of J. New York, USA: Random House.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clontz, T.E. and J. (2008). "The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh. Cornerstone Publications. pp. 476, 497. ISBN 978-0-977873-71-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Copan, Paul (1996). "Is Creatio Ex Nihilo A Post-Biblical Invention?: An Examination Of Gerhard May's Proposal". 17. Trinity Journal: 77–93.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Davis, John (1975). Paradise to Prison—Studies in Genesis. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House. p. 23.

- Douglas, A. Vibert (1956). ""Forty Minutes with Einstein". 50. Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada: 100.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Douglas, J.D.; et al. (1990). Old Testament Volume: New Commentary on the Whole Bible. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale,.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Ellis, George F. R. (1993). Before the Beginning: Cosmology Explained. London and New York: Boyars/Bowerdean. p. 97.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fain, Benjamin (2007). Creation Ex Nihilo: Thoughts on Science, Divine Providence, Free Will, and Faith in the Perspective of My Own Experiences. pp. 30–36.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Friedman, Richard E. (2003). Commentary on the Torah. HarperOne. ISBN 0060625619.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Friedman, Richard E. (1987). Who Wrote The Bible?. NY, USA: Harper and Row. ISBN 0060630353.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gunkel, Hermann (1894). Schöpfung und Chaos in Urzeit und Endzeit. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hamilton, Victor P (1990). The Book of Genesis. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heeren, Fred (2000). Show Me God: What the Message from Space Is Telling Us About God. Day Star Publications. pp. 107–108, 121, 135, 157.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heidel, Alexander (1963). Babylonian Genesis (2nd ed.). Chicago University Press. ISBN 0226323994.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Heidel, Alexander (1963). Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels (2nd Revised ed.). Chicago University Press. ISBN 0226323986.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Herbert, Nick (1985). Quantum Reality: Beyond the New Physics. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press/Doubleday. p. 177.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jastrow, Robert (1992). God and the Astronomers (2nd ed.). New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 14.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - King, Leonard (2007). Enuma Elish: The Seven Tablets of Creation; The Babylonian and Assyrian Legends Concerning the Creation of the World and of Mankind. Vol. 1 and 2. Cosimo Inc. ISBN 1602063192.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - May, Gerhard (1994). Creatio ex Nihilo: The Doctrine of "Creation out of Nothing" in Early Christian Thought (English version ed.). Edinburgh: T & T Clark.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nicholson, Ernest (2003). The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century: The Legacy of Julius Wellhausen. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Parker, Barry (1988). Creation: the Story of the Origin and Evolution of the Universe. New York & London: Plenum Press. p. 202.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Penchansky, David (2005). Twilight of the Gods: Polytheism in the Hebrew Bible (Interpretation Bible Studies). U.S.: Westminster/John Knox Press. ISBN 0664228852.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Reis, Pamela Tamarkin (2001). "Genesis as "Rashomon": The creation as told by God and man". 17 (3). Bible Review.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rouvière, Jean-Marc (2006). Brèves méditations sur la création du monde (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schaff, Philip (1995). "The Confessions and Letters of Augustine with a Sketch of his Life and Work". The Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers. First. Vol. 1. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 1565630955.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, George (2004). The Chaldean account of Genesis: Containing the description of the creation, the fall of man, the deluge, the tower of Babel, the times of the ... of the gods; from the cuneiform inscriptions. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1402150997.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel (2nd ed.). William B Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 080283972X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Smith, Mark S. (2003). The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts (New Ed ed.). Oxford University Press USA. ISBN 0195167686.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Smoot, George; Davidson, Keay (1993). Wrinkles in Time. New York: William Morrow and Company. pp. 30, 189.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spurrell, G.J. (1896). Notes on the Text of the Book of Genesis. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tigay, Jeffrey (1986). Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism. Philadelphia, PA, USA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tsumura, David Toshio (2005). "The Earth in Genesis 1; The Waters in Genesis 1; The Earth in Genesis 2; The Waters in Genesis 2". Creation and destruction: a reappraisal of the Chaoskampf theory in the Old Testament (Revised and expanded ed.). Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061061.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walton, John H. (2006). Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Baker Academic. ISBN 0801027500.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Wenham, Gordon (1987). Genesis 1-15. Vol. 1 and 2. Word Books.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yonge, Charles Duke (1854). "Appendices A Treatise Concerning the World (1), On the Creation (16-19, 26-30), Special Laws IV (187), On the Unchangeableness of God (23-32)". The Works of Philo Judaeus: the contemporary of Josephus. London: H. G. Bohn.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

Sources for the Biblical text

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (Hebrew-English text, translated according to the JPS 1917 Edition)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 (Hebrew-English text, with Rashi's commentary. The translation is the authoritative Judaica Press version, edited by the esteemed translator and scholar, Rabbi A.J. Rosenberg.)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (King James Version)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (Revised Standard Version)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New Living Translation)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New American Standard Bible)

- Chapter 1 Chapter 2 (New International Version (UK))

Sources for earlier related Mesopotamian texts

- "Enuma Elish", at Encyclopedia of the Orient Summary of Enuma Elish with links to full text.

- ETCSL—Text and translation of the Eridu Genesis (alternate site) (The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford)

- "Epic of Gilgamesh" (summary)

- British Museum: Cuneiform tablet from Sippar with the story of Atra-Hasis

Other resources

- Alexander Heidel, "Babylonian Genesis" A classic text, at Wikibooks

- Comparing the myths of Adapa and Adam, prototypes of priest and humankind (summary of Liverani's views)

- Hexaemeron—Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Jacob Boehme's vision on Genesis His book Mysterium Magnum.

- Mark S. Smith, "The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts", Bible and Interpretation.

- Paul H. Seely, "The Firmament and the Water Above", The Westminster Theological Journal 53 (1991) ANE cosmography

- Paul H. Seely, "The Geographical Meaning of 'Éarth' and 'Seas' in Genesis 1:10", Westminster Theological Journal 59 (1997) ANE cosmography.

- Philo—On the Creation

- Philo—Questions and Answers on Genesis

- Religious practices in late 7th century Israel

- Review of Benjamin R. Foster, Before the Muses: An Anthology of Akkadian Literature (2005) Includes comments on parallels between ancient Mesopotamian literature and biblical texts.

- Review of James P. Allen, The Egyptian Pyramid Texts (2005)

- Review of John Day, Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan (2000).

- Six Days of Creation: Islamic View

- The Multiple Authorship of the Books Attributed to Moses