Mount Fuji

| Mount Fuji | |

|---|---|

Mount Fuji seen from Ōwakudani (2021) | |

| Highest point | |

| Prominence | 3,776 m (12,388 ft)[1] Ranked 35th |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 35°21′39″N 138°43′39″E / 35.36083°N 138.72750°E[2] |

| Naming | |

| Native name | 富士山 (Japanese) |

| Pronunciation | [ɸɯꜜ(d)ʑisaɴ] |

| Geography | |

| Location | Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park |

| Country | Japan |

| Prefectures | |

| Municipalities | |

| Topo map(s) | Geospatial Information Authority 25000:1 富士山[3] 50000:1 富士山 |

| Geology | |

| Rock age | 100,000 years |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Last eruption | 1707–08 |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 663 by En no Odzunu (役行者, En no gyoja, En no Odzuno) |

| Easiest route | Hiking |

| Official name | Fujisan, sacred place and source of artistic inspiration |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, vi |

| Reference | 1418 |

| Inscription | 2013 (37th Session) |

| Area | 20,702.1 ha |

| Buffer zone | 49,627.7 ha |

| Mount Fuji | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Mt. Fuji" in kanji | |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 富士山 | ||||||

| Hiragana | ふじさん | ||||||

| |||||||

Mount Fuji (富士山, Fujisan, Japanese: [ɸɯꜜ(d)ʑisaɴ] ⓘ) is an active stratovolcano located on the Japanese island of Honshu, with a summit elevation of 3,776.24 m (12,389 ft 3 in). It is the highest mountain in Japan, the second-highest volcano located on an island in Asia (after Mount Kerinci on the Indonesian island of Sumatra), and seventh-highest peak of an island on Earth.[1] Mount Fuji last erupted from 1707 to 1708.[4][5] The mountain is located about 100 km (62 mi) southwest of Tokyo and is visible from the Japanese capital on clear days. Mount Fuji's exceptionally symmetrical cone, which is covered in snow for about five months of the year, is commonly used as a cultural icon of Japan and is frequently depicted in art and photography, as well as visited by sightseers, hikers and mountain climbers.[6]

Mount Fuji is one of Japan's "Three Holy Mountains" (三霊山, Sanreizan) along with Mount Tate and Mount Haku. It is a Special Place of Scenic Beauty and one of Japan's Historic Sites.[7] It was added to the World Heritage List as a Cultural Site on June 22, 2013.[7] According to UNESCO, Mount Fuji has "inspired artists and poets and been the object of pilgrimage for centuries". UNESCO recognizes 25 sites of cultural interest within the Mount Fuji locality. These 25 locations include the mountain and the Shinto shrine, Fujisan Hongū Sengen Taisha.[8]

Etymology

The current kanji for Mount Fuji, 富 and 士, mean "wealth" or "abundant" and "man of status" respectively. However, the origins of this spelling and of the name Fuji continue to be debated.

A text of the 9th century, Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, says that the name came from "immortal" (不死, fushi, fuji) and also from the image of abundant (富, fu) soldiers (士, shi, ji)[note 1] ascending the slopes of the mountain.[9] An early folk etymology claims that Fuji came from 不二 (not + two), meaning without equal or nonpareil. Another claims that it came from 不盡 (not + to exhaust), meaning never-ending.

Hirata Atsutane, a Japanese classical scholar in the Edo period, speculated that the name is from a word meaning "a mountain standing up shapely as an ear (穗, ho) of a rice plant". British missionary John Batchelor (1855–1944) argued that the name is from the Ainu word for "fire" (fuchi) of the fire deity Kamui Fuchi, which was denied by a Japanese linguist Kyōsuke Kindaichi on the grounds of phonetic development (sound change). It is also pointed out that huchi means an "old woman" and ape is the word for "fire", ape huchi kamuy being the fire deity. Research on the distribution of place names that include fuji as a part also suggest the origin of the word fuji is in the Yamato language rather than Ainu. Japanese toponymist Kanji Kagami argued that the name has the same root as wisteria (藤, fuji) and rainbow (虹, niji, but with an alternative reading, fuji), and came from its "long well-shaped slope".[10][11][12][13]

Modern linguist Alexander Vovin proposes an alternative hypothesis based on Old Japanese reading */puⁿzi/: the word may have been borrowed from Eastern Old Japanese */pu nusi/ 火主, meaning "fire master".[14]

Variations

In English, the mountain is known as Mount Fuji. Some sources refer to it as "Fuji-san", "Fujiyama" or, redundantly, "Mt. Fujiyama". Japanese speakers refer to the mountain as "Fuji-san". This "san" is not the honorific suffix used with people's names, such as Watanabe-san, but the Sino-Japanese reading of the character yama (山, "mountain") used in Sino-Japanese compounds. In Nihon-shiki and Kunrei-shiki romanization, the name is transliterated as Huzi.

Other Japanese names which have become obsolete or poetic include Fuji-no-Yama (ふじの山, "the Mountain of Fuji"), Fuji-no-Takane (ふじの高嶺, "the High Peak of Fuji"), Fuyō-hō (芙蓉峰, "the Lotus Peak"), and Fugaku (富岳/富嶽), created by combining the first character of 富士, Fuji, and 岳, mountain.[15]

History

Mount Fuji is an attractive volcanic cone and has been a frequent subject of Japanese art especially after 1600, when Edo (now Tokyo) became the capital and people saw the mountain while traveling on the Tōkaidō road. According to the historian H. Byron Earhart, "in medieval times it eventually came to be seen by Japanese as the "number one" mountain of the known world of the three countries of India, China, and Japan".[16] The mountain is mentioned in Japanese literature throughout the ages and is the subject of many poems.[17]

The summit has been thought of as sacred since ancient times and was therefore forbidden to women. It was not until 1872 that the Japanese government issued an edict (May 4, 1872, Grand Council of State Edict 98) stating, "Any remaining practices of female exclusion on shrine and temple lands shall be immediately abolished, and mountain climbing for the purpose of worship, etc., shall be permitted."[18] Tatsu Takayama, a Japanese woman, became the first woman on record to summit Mount Fuji in the fall of 1832.[19][20][21]

Ancient samurai used the base of the mountain as a remote training area, near the present-day town of Gotemba. The shōgun Minamoto no Yoritomo held yabusame archery contests in the area in the early Kamakura period.

The first ascent by a foreigner was by Sir Rutherford Alcock in September 1860, who ascended the mountain in 8 hours and descended in 3 hours.[22]: 427 Alcock's brief narrative in The Capital of the Tycoon was the first widely disseminated description of the mountain in the West.[22]: 421–27 Lady Fanny Parkes, the wife of British ambassador Sir Harry Parkes, was the first non-Japanese woman to ascend Mount Fuji, in 1867.[23] Photographer Felix Beato climbed Mount Fuji two years later.[24]

On March 5, 1966, BOAC Flight 911, a Boeing 707, broke up in flight and crashed near the Mount Fuji Gotemba New fifth station, shortly after departure from Tokyo International Airport. All 113 passengers and 11 crew members died in the disaster, which was attributed to the extreme clear-air turbulence caused by lee waves downwind of the mountain. There is a memorial for the crash victims a short distance down from the Gotemba New fifth station.[25]

Today, Mount Fuji is an international destination for tourism and mountain climbing.[26][27] In the early 20th century, populist educator Frederick Starr's Chautauqua lectures about his several ascents of Mount Fuji— in 1913, 1919, and 1923—were widely known in America.[28] A well-known Japanese saying suggests that a wise person will climb Mt. Fuji once in their lifetime, but only a fool would climb it twice.[29][30] It remains a popular symbol in Japanese culture, including making numerous movie appearances,[31] inspiring the Infiniti logo,[32] and even appearing in medicine with the Mount Fuji sign.[33][34]

In September 2004, the staffed weather station at the summit was closed after 72 years in operation. Observers monitored radar sweeps that detected typhoons and heavy rains. The station, which was the highest in Japan at 3,780 m (12,402 ft), was replaced by a fully automated meteorological system.[35]

Mount Fuji was added to the World Heritage List as a Cultural Site on June 22, 2013.[7]

Geography

Mount Fuji is a very distinctive feature of the geography of Japan. It stands 3,776.24 m (12,389 ft) tall and is located near the Pacific coast of central Honshu, just southwest of Tokyo. It straddles the boundary of Shizuoka and Yamanashi prefectures. Four small cities surround it - Gotemba to the east, Fujiyoshida to the north, Fujinomiya to the southwest, and Fuji to the south - as well as several towns and villages in the area. It is surrounded by five lakes: Lake Kawaguchi, Lake Yamanaka, Lake Sai, Lake Motosu and Lake Shōji.[36] They, and nearby Lake Ashi in Kanagawa Prefecture, provide expansive views of the mountain. The mountain is part of the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park. It can be seen more distantly from Yokohama, Tokyo, and sometimes as far as Chiba, Saitama, Tochigi, Ibaraki and Lake Hamana when the sky is clear. It has been photographed from space during a space shuttle mission.[37]

Climate

The summit of Mount Fuji has a tundra climate (Köppen climate classification ET). The temperature is very low at the high altitude, and the cone is covered by snow for several months of the year. The lowest recorded temperature is −38.0 °C (−36.4 °F) recorded in February 1981, and the highest temperature was 17.8 °C (64.0 °F) recorded in August 1942.

Fuji's seasonal snowcap begins at an average date of 2 October. In 2024, the snowcap formed on 6 November, the latest-occurring since records began in 1894.[38]

| Climate data for Mt. Fuji (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1932–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

16.3 (61.3) |

14.0 (57.2) |

6.9 (44.4) |

3.6 (38.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −15.3 (4.5) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

6.5 (43.7) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −18.2 (−0.8) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

−14.1 (6.6) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

−15.1 (4.8) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −21.4 (−6.5) |

−21.1 (−6.0) |

−17.7 (0.1) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

2.8 (37.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −37.3 (−35.1) |

−38.0 (−36.4) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−13.1 (8.4) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−19.5 (−3.1) |

−28.1 (−18.6) |

−33.0 (−27.4) |

−38.0 (−36.4) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 53 | 56 | 61 | 63 | 60 | 70 | 79 | 75 | 67 | 53 | 52 | 52 | 62 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[39] | |||||||||||||

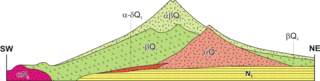

Geology

Mount Fuji is located at a triple junction trench where the Amurian Plate, Okhotsk Plate, and Philippine Sea Plate meet.[41][42] These three plates form the western part of Japan, the eastern part of Japan, and the Izu Peninsula respectively.[43] The Pacific Plate is being subducted beneath these plates, resulting in volcanic activity. Mount Fuji is also located near three island arcs: the Southwestern Japan Arc, the Northeastern Japan Arc, and the Izu-Bonin-Mariana Arc.[43] The Fuji triple junction is only 400 kilometres (250 mi) from the Boso triple junction.

Fuji's main crater is 780 m (2,560 ft) in diameter and 240 m (790 ft) deep. The bottom of the crater is 100–130 m (330–430 ft) in diameter. Slope angles from the crater to a distance of 1.5–2 km (0.93–1.24 mi) are 31°–35°, the angle of repose for dry gravel. Beyond this distance, slope angles are about 27°, which is caused by an increase in scoria. Mid-flank slope angles decrease from 23° to less than 10° in the piedmont.[43]

Scientists have identified four distinct phases of volcanic activity in the formation of Mount Fuji. The first phase, called Sen-komitake, is composed of an andesite core recently discovered deep within the mountain. Sen-komitake was followed by the "Komitake Fuji", a basalt layer believed to be formed several hundred thousand years ago. Approximately 100,000 years ago, "Old Fuji" was formed over the top of Komitake Fuji. The modern, "New Fuji" is believed to have formed over the top of Old Fuji around 10,000 years ago.[44]

Pre-Komitake started erupting in the Middle Pleistocene in an area seven km (4+1⁄2 mi) north of Mount Fuji. After a relatively short pause, eruptions began again which formed Komitake Volcano in the same location. These eruptions ended 100,000 years ago. Ashitake Volcano was active from 400,000 to 100,000 years ago and is located 20 km (12 mi) southeast of Mount Fuji. Mount Fuji started erupting 100,000 years ago, with Ko-Fuji (old-Fuji) forming 100,000 to 17,000 years ago, but which is now almost completely buried. A large landslide on the southwest flank occurred about 18,000 years ago. Shin-Fuji (new-Fuji) eruptions in the form of lava, lapilli and volcanic ash, have occurred between 17,000 and 8,000 years ago, between 7,000 and 3,500 years ago, and between 4,000 and 2,000 years ago. Flank eruptions, mostly in the form of parasitic cinder cones, ceased in 1707. The largest cone, Omuro-Yama, is one of more than 100 cones aligned NW-SE and NE-SW through the summit. Mt. Fuji also has more than 70 lava tunnels and extensive lava tree molds. Two large landslides are at the head of the Yoshida-Osawa and Osawa-Kuzure valleys.[43]

As of December 2002[update], the volcano is classified as active with a low risk of eruption. The last recorded eruption was the Hōei eruption which started on December 16, 1707 (Hōei 4, 23rd day of the 11th month), and ended about January 1, 1708 (Hōei 4, 9th day of the 12th month).[45] The eruption formed a new crater and a second peak, named Mount Hōei, halfway down its southeastern side. Fuji spewed cinders and ash which fell like rain in Izu, Kai, Sagami, and Musashi.[46] Since then, there have been no signs of an eruption. However, on the evening of March 15, 2011, there was a magnitude 6.2 earthquake at shallow depth a few kilometres from Mount Fuji on its southern side.

Recorded eruptions

About 11,000 years ago, a large amount of lava began to erupt from the west side of the top of the ancient Fuji mountain. This lava formed the new Fuji which is the main body of Mount Fuji. Since then, the tops of the ancient Fuji and the new Fuji are side by side. About 2,500–2,800 years ago, the top part of ancient Fuji caused a large-scale landslide due to weathering, and finally, only the top of Shin-Fuji remained. There are ten known eruptions that can be traced to reliable records.[47][48]

| Date(s) | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| July 31, 781 | The eruption was recorded in the Shoku Nihongi and it was noted that "ash fell", but there are no other details. | [49] |

| April 11 – May 15, 800 February 13, 802 |

The Nihon Kiryaku states that during the first phase, the skies were dark even during the daytime. The second phase is known from the Nippon Kiseki, which notes that gravel fell like hail. | [50] |

| June–September 864 December 865 – January 866 |

Both phases were recorded in the Nihon Sandai Jitsuroku. This eruption created three of the Fuji Five Lakes: Motosu, Shōji, and Saiko, from a single lake that became separated by lava flow. | [51] |

| November 937 | This was recorded in the Nihon Kiryaku. | [52] |

| March 999 | It is noted in the Honchō Seiki that news of an eruption was brought to Kyoto, but no other details are known. | [53] |

| January 1033 | According to the Nihon Kiryaku, news of this eruption was brought to Kyoto two months later. | [54] |

| April 17, 1083 | The only contemporary recording of this was written by a Buddhist monk and can be found in the Fusō Ryakuki. Later writings indicate that the sound of the eruption may have been heard in Kyoto. | [55] |

| between January 30, 1435, and January 18, 1436 | A record of this appears in the Ōdaiki, a chronicle kept by the monks at Kubo Hachiman Shrine in Yamanashi City and it states that a flame was visible on Mount Fuji. As there is no mention of smoke, this appears to have been a Hawaiian eruption (lava only). | [56] |

| August 1511 | The Katsuyamaki (or Myōhōjiki), written by monks at Myōhō-ji in Fujikawaguchiko, indicates that there was a fire on Mount Fuji at this time, but as there is no vegetation at the described location, this was almost certainly a lava flow. | [57] |

| December 16, 1707 | The Hōei eruption | [45] |

Current eruptive danger

This section needs to be updated. (November 2022) |

Following the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake, there was speculation in the media that the shock may induce volcanic unrest at Mount Fuji. In September 2012, mathematical models created by the National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention (NRIESDP) suggested that the pressure in Mount Fuji's magma chamber could be 1.6 megapascals higher than it was before its last eruption in 1707. This was interpreted by some media outlets to mean that an eruption of Mount Fuji could be imminent.[58] However, since there is no known method of directly measuring the pressure of a volcano's magma chamber, indirect calculations of the type used by NRIESDP are speculative and unverifiable. Other indicators suggestive of heightened eruptive danger, such as active fumaroles and recently discovered faults, are typical occurrences at this type of volcano.[59]

Eruption fears continued into the 2020s. In 2021, a new hazard map was created to help residents plan for evacuation, stoking fears because of its increased estimate of lava flow and additional vents.[60] Soon afterwards, a 4.8 magnitude earthquake hit the area, sending the phrase "Mt Fuji eruption" trending on Twitter.[61] However, the Japan Meteorological Agency assured the public the earthquake did not increase the eruption risk. In 2023, a new evacuation plan was developed to account for the 2021 hazard map update.[62]

Aokigahara forest

The forest at the northwest base of the mountain is named Aokigahara. Folk tales and legends tell of ghosts, demons, Yūrei and Yōkai haunting the forest, and in the 19th century, Aokigahara was one of many places poor families abandoned the very young and elderly.[63] Approximately 30 suicides have been counted yearly, with a high of nearly 80 bodies in 2002.[64] The recent increase in suicides prompted local officials to erect signs that attempt to convince individuals experiencing suicidal intent to re-think their desperate plans, and sometimes these messages have proven effective.[65] The numbers of suicides in the past creates an allure that has persisted across the span of decades.[66][67]

Many hikers mark their routes by leaving colored plastic tape behind as they pass, raising concern among prefectural officials about the forest's ecosystem.[68]

Adventuring

Transportation

The closest airport with scheduled international service is Mt. Fuji Shizuoka Airport. It opened in June 2009. It is about 80 km (50 mi) from Mount Fuji.[69] The major international airports serving Tokyo, Tokyo International Airport (Haneda Airport) in Tokyo and Narita International Airport in Chiba are approximately three hours and 15 minutes from Mount Fuji.

Climbing routes

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2022) |

Approximately 300,000 people climbed Mount Fuji in 2009.[70] The most popular period for people to hike up Mount Fuji is from July to August, while huts and other facilities are operating and the weather is warmest.[70] Buses to the trail heads typically used by climbers start running on July 1.[71] Climbing from October to May is very strongly discouraged, after a number of high-profile deaths and severe cold weather.[72] Most Japanese climb the mountain at night in order to be in a position at or near the summit when the sun rises. The morning light is called 御来光 goraikō, "arrival of light".[73]

There are four major routes to the summit, each has numbered stations along the way. They are (clockwise, starting north): Kawaguchiko, Subashiri, Gotemba, and Fujinomiya routes.[74] Climbers usually start at the fifth stations, as these are reachable by car or by bus. The summit is the tenth station on each trail. The stations on different routes are at different elevations; the highest fifth station is located at Fujinomiya, followed by Yoshida, Subashiri, and Gotemba. There are four additional routes from the foot of the mountain: Shojiko, Yoshida, Suyama, and Murayama routes.[75]

Even though it has only the second-highest fifth station, the Yoshida route is the most popular route because of its large parking area and many large mountain huts where a climber can rest or stay. During the summer season, most Mount Fuji climbing tour buses arrive there. The next most popular is the Fujinomiya route, which has the highest fifth station, followed by Subashiri and Gotemba. The ascent from the new fifth station can take anywhere between five and seven hours while the descent can take from three to four hours.[74] Even though most climbers do not use the Subashiri and Gotemba routes, many descend these because of their ash-covered paths. From the seventh station to near the fifth station, one could run down these ash-covered paths in approximately 30 minutes.

There are also tractor routes along the climbing routes. These tractor routes are used to bring food and other materials to huts on the mountain. Because the tractors usually take up most of the width of these paths and they tend to push large rocks from the side of the path, the tractor paths are off-limits to the climbers on sections that are not merged with the climbing or descending paths. Nevertheless, one can sometimes see people riding mountain bikes along the tractor routes down from the summit. This is particularly risky, as it becomes difficult to control speed and may send some rocks rolling along the side of the path, which may hit other people.

The four routes from the foot of the mountain offer historical sites. The Murayama is the oldest route, and the Yoshida route still has many old shrines, teahouses, and huts along its path. These routes are gaining popularity recently and are being restored, but climbing from the foot of the mountain is still relatively uncommon. Bears that live on the mountain have been sighted along the Yoshida route.

Huts at and above the fifth stations are usually staffed during the climbing season, but huts below fifth stations are not usually staffed for climbers. The number of open huts on routes are proportional to the number of climbers—Yoshida has the most while Gotemba has the fewest. The huts along the Gotemba route also tend to start later and close earlier than those along the Yoshida route. Also, because Mount Fuji is designated as a national park, it is illegal to camp above the fifth station.

There are eight peaks around the crater at the summit. The highest point in Japan, Ken-ga-mine, is where the Mount Fuji Radar System used to be (it was replaced by an automated system in 2004). Climbers are able to visit each of these peaks.

Paragliding

Paragliders take off in the vicinity of the fifth station Gotemba parking lot, between Subashiri and Hōei-zan peak on the south side of the mountain, in addition to several other locations, depending on wind direction. Several paragliding schools use the wide sandy/grassy slope between Gotemba and Subashiri parking lots as a training hill.

Overtourism concerns

On 1 February 2024, the Yamanashi prefectural government imposed a mandatory fee of 2,000 yen ($13) for hikers using the Yoshida trail beginning in the summer season as part of efforts to ease congestion and provide funding for safety protocols.[76] It later announced that it would impose a daily limit of 4,000 hikers on the trail and close it between 4 p.m. and 3 a.m except for guests in mountain lodges.[77] The Shizuoka prefectural government subsequently announced that it would also close the Subashiri, Gotemba and Fujinomiya trails at the same time period with the same exceptions, citing also concerns over congestion.[78]

In culture

Shinto mythology

In Shinto mythology, Kuninotokotachi (国之常立神?, Kuninotokotachi-no-Kami, in Kojiki)(国常立尊?, Kuninotokotachi-no-Mikoto, in Nihon Shoki) is one of the two gods born from "something like a reed that arose from the soil" when the earth was chaotic. According to the Nihon Shoki, Konohanasakuya-hime, wife of Ninigi, is the goddess of Mount Fuji, where Fujisan Hongū Sengen Taisha is dedicated for her.

In ancient times, the mountain was worshipped from afar. The Asama shrine was set up at the foothills to ward off eruptions. In the Heian period (794–1185), volcanic activity subsided and Fuji was used as a base for Shugendō, a syncretic religion combining mountain worship and Buddhism. Worshippers began to climb the slopes and by the early 12th century, Matsudai Shonin had founded a temple on the summit.[79]

Fuji-kō was an Edo period cult centred around the mountain founded by an ascetic named Hasegawa Kakugyō (1541–1646).[80] The cult venerated the mountain as a female deity, and encouraged its members to climb it. In doing so they would be reborn, "purified and... able to find happiness." The cult waned in the Meiji period and although it persists to this day it has been subsumed into Shintō sects.[80]

Popular culture

As a national symbol of the country, the mountain has been depicted in various art media such as paintings, woodblock prints (such as Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji and 100 Views of Mount Fuji from the 1830s), poetry, music, theater, film, manga, anime, pottery[81] and even Kawaii subculture.

Before its explosive eruption in 1980, Mount St. Helens was once known as "The Fuji of America", for its striking resemblance to Mount Fuji. Mount Taranaki in New Zealand is also said to bear a resemblance to Mount Fuji, and for this reason has been used as a stand-in for the mountain in films and television.

See also

- List of mountains and hills of Japan by height

- 100 Famous Japanese Mountains

- List of three-thousanders in Japan

- List of World Heritage sites in Japan

- List of elevation extremes by country

- Mount Araido (阿頼度山, Araidosan), Araido Island (阿頼度島), Kuril Islands

Notes

- ^ Although the word 士 can mean a soldier (兵士, heishi, heiji), or a samurai (武士, bushi), its original meaning is a man with a certain status.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b "Fujisan jōhō kōnā" 富士山情報コーナー [Mt. Fuji information corner] (in Japanese). Sabo Works at Mt.Fuji. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ "Nihon no omona sangaku" 日本の主な山岳 [Japan's main mountains] (in Japanese). Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ "Chizu etsuran sābisu 2 man 5 sen-bu 1 chikei-zu-mei: Fujisan (Kōfu)" 地図閲覧サービス 2万5千分1地形図名: 富士山(甲府) [Map viewing service 1:25,000 topographic map name: Mt. Fuji (Kofu)] (in Japanese). Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- ^ "Active Volcanoes of Japan". Quaternary Volcanoes of Japan. Geological Survey of Japan. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Mount Fuji". Britannica Online. Archived from the original on October 29, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States: Reader's Digest Association. p. 153. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- ^ a b c "Japan's Mt. Fuji granted World Heritage status". CNA. June 22, 2013. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Fujisan, sacred place and source of artistic inspiration". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on October 17, 2022. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Taketorimonogatari kaguyahime no o hi-tachi 竹取物語 かぐや姫のおひたち [The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter: Kaguyahime's Ohitachi]. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten. 1929 – via Japanese Text Initiative.

ja:竹取物語 かぐや姫のおひたち at Wikibooks

ja:竹取物語 かぐや姫のおひたち at Wikibooks

- ^ "Fujisan no namaenoyurai" 富士山の名前の由来 [Origin of the name Mt. Fuji] (in Japanese). May 31, 2008. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Fujisan" 富士山 [Mt. Fuji]. Chisen Wiki (in Japanese). October 25, 2006. Archived from the original on December 18, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Chimei Fujisan no imi" 地名・富士山の意味 [Meaning of place name Mt. Fuji] (in Japanese). June 3, 2008. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Fujisan ainukotoba gogen-setsu ni tsuite" 富士山アイヌ語語源説について [About the etymology of the Ainu language of Mt. Fuji] (in Japanese). Asahi-net.or.jp. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (January 1, 2017). "On the Etymology of the Name of Mt. Fuji". In Vovin, Alexander; McClure, William (eds.). Studies in Japanese and Korean Historical and Theoretical Linguistics and Beyond. Languages of Asia. Vol. 16. Brill. pp. 80–89. doi:10.1163/9789004351134_010. ISBN 9789004351134. Retrieved November 15, 2023.

- ^ "Fuji-san" (in Japanese). Daijisen. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011.

- ^ Earhart, H. Byron (May 9, 2011). "Mount Fuji: Shield of War, Badge of Peace". The Asia-Pacific Journal. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Fuse, Mitsutoshi (2003). Fujisan Yoshidaguchi tozan-dō kanren iseki 富士山吉田口登山道関連遺跡 [Mt. Fuji Yoshidaguchi trail related ruins] (Technical report). Fujiyoshida City Cultural Properties Investigation Report (in Japanese). Vol. 4. Fujiyoshida City Board of Education. doi:10.24484/sitereports.6470.

- ^ DeWitt, Lindsey E. (March 2016). "Envisioning and Observing Women's Exclusion from Sacred Mountains in Japan". Journal of Asian Humanities at Kyushu University. 1: 19–28. doi:10.5109/1654566. hdl:1854/LU-8636481. ISSN 2433-4855. S2CID 55419374.

- ^ Budgen, Mara (July 4, 2022). "Climb every mountain: Japan's female mountaineers scale new heights". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ "Takayama Tatsu (takaya ma tatsu) to wa? Imi ya tsukaikata" 高山たつ(たかやま・たつ)とは? 意味や使い方 [Who is Tatsu Takayama? Meaning and usage]. Asahi Nihon rekishi jinbutsu jiten 朝日日本歴史人物事典 [Asahi Dictionary of Japanese Historical Figures] (in Japanese). The Asahi Shimbun Company. 1994. ISBN 9784023400528. Retrieved November 19, 2023 – via Kotobank.

- ^ Intersect. Vol. 9–10. PHP Institute. 1993. p. 39.

- ^ a b Alcock, Rutherford (1863). The Capital of the Tycoon: A Narrative of Three Years Residence in Japan. Vol. I. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ "#259, Lilian Hope Parkes". The Cobbold Family History Trust. Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

- ^ Tucker, Anne; Iizawa, Kōtarō; Friis-Hansen, Dana; Ryuichi, Kaneko; Kinoshita, Naoyuki; Joe, Takeba; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Kokusai Kaoryau Kikin Staff (2003). Tucker, Anne; Iizawa, Kōtarō; Junkerman, John; Masayuki, Kuriyama; Maya, Ishiwata; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Rie, Imai; Cleveland Museum of Art (eds.). The History of Japanese Photography. Translated by Junkerman, John. Yale University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-300-09925-6.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 707-436 G-APFE Mount Fuji". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. Archived from the original on October 28, 2011. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ^ "Climbing Mount Fuji? route maps" (PDF). pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ^ "Climbing Mt. Fuji travel log". ChristmasWhistler. June 30, 2002. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ "Starr Tells of Escape: American Scientist Found Refuge in a Tokio Temple". The New York Times. New York. October 1, 1923. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ Tuckerman, Mike. "Climbing Mount Fuji". JapanVisitor. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ Bremmer, Brian (September 15, 1997). "Mastering Mt. Fuji". Business Week. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013.

- ^ Uchida, Tomu (1955). Chiyarifuji 血槍富士 [Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji] (in Japanese).

- ^ "Launching Infiniti". Lippincott Mercer. Archived from the original on October 30, 2006.

- ^ Sadeghian, Hamid (September 2000). "Mount Fuji Sign in Tension Pneumocephalus". Archives of Neurology. 57 (9): 1366. doi:10.1001/archneur.57.9.1366. PMID 10987907.

- ^ Heckmann, Josef G.; Ganslandt, Oliver (April 2004). "Images in clinical medicine. The Mount Fuji sign". The New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (18): 1881. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm020479. PMID 15115834.

- ^ "Weather Station on Mt. Fuji Closes". Tokyo: United Press International. September 30, 2004. Archived from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ "Fujisan". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ "STS-107 Shuttle Mission Imagery". NASA. January 26, 2003. Archived from the original on February 10, 2003. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ "Snow seen on Mount Fuji after record absence". CNA. November 6, 2024. Retrieved November 7, 2024.

- ^ "Heinen-chi (-nen tsuki-goto no atai)" 平年値(年・月ごとの値) [Normal value (yearly/monthly value)] (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Miyaji, Naomichi. "Geology of Fuji Volcano". Hokkaido National Agricultural Experiment Station. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2023 – via Volcano Research Center, Earthquake Research Institute (ERI), University of Tokyo.

- ^ Moores, Eldridge M.; Twiss, Robert J. (2014). Tectonics. Waveland Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4786-2199-7.

- ^ "Mount Fuji". National Geographic Society. December 6, 2011. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Oguchi, Takashi; Oguchi, Chiaki (2010). "Mt. Fuji: The Beauty of a Symmetric Stratovolcano". In Migon, Piotr (ed.). Geomorphological Landscapes of the World. Springer Netherlands. pp. 303–309. ISBN 9789048130542.

- ^ "Third ancient volcano discovered within Mount Fuji". Japan Times. April 4, 2004. Archived from the original on March 11, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Koyama, Masato. "Hōei shi-nen (1707) funka" 宝永四年(1707)噴火 [Eruption in the fourth year of Hōei (1707)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Gahō, Hayashi (1834) [Originally published 1652]. von Klaproth, Julius (ed.). Nipon o daï itsi ran; ou, Annales des empereurs du Japon [Nipon o daï itsi ran; or, Annals of the Emperors of Japan] (in French). Translated by Titsingh, Isaac. Paris: Oriental Translation Society of Great Britain and Ireland. p. 416.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Database of eruptions and other activities of Fuji Volcano, Japan, based on historical records since AD781" (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "All about Mount Fuji". pandoraboss.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Ten'nō gan'nen (781) funka" 天応元年(781)噴火 [Eruption in the first year of Ten'ō (781)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Nobe-reki jū kyū ~ nijūichinen (800 ~ 802) funka" 延暦十九~二十一年(800~802)噴火 [Eruption in the 19th to 21st years of Enryaku (800 to 802)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Jōgan roku ~ nana-nen (864 ~ 866 shotō) funka" 貞観六~七年(864~866初頭)噴火 [Eruption in the 6th to 7th years of Jōgan (864 to early 866)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Jōhei nana-nen (937) funka" 承平七年(937)噴火 [Eruption in the 7th year of Jōhei (937)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Chōhō gan'nen (999) funka" 長保元年(999)噴火 [Eruption in the first year of Chōhō (999)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Chō gen go nenmatsu (1033 shotō) funka" 長元五年末(1033初頭)噴火 [Eruption at the end of Chōgen 5 (early 1033)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Nagayasu san-nen (1083) funka" 永保三年(1083)噴火 [Eruption in the third year of Eihō (1083)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Eikyō nana-nen (1435 matawa 1436 shotō) funka" 永享七年(1435または1436初頭)噴火 [Eruption in the seventh year of Eikyō (1435 or early 1436)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ Koyama, Masato. "Eishō hachi-nen (1511) funka" 永正八年(1511)噴火 [Eruption in the eighth year of Eishō (1511)] (in Japanese). Shizuoka University. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Clark, Liat (September 6, 2012). "Pressure in Mount Fuji is now higher than last eruption, warn experts". Wired. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Klemetti, Erik (September 10, 2012). "Doooom! The Perception of Volcano Research by the Media". Wired. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Ryall, Julian (April 7, 2021). "Japan: Mount Fuji report doubles estimate of lava flow". Tokyo: Deutsche Welle. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "Japan quells fears of Mt Fuji eruption after earthquake". Reuters. December 2, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "Mount Fuji eruption escape plan calls on residents to evacuate on foot". The Japan Times. March 29, 2023. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "Japan's harvest of death". The Independent. October 24, 2000. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Hadfield, Peter (November 5, 2000). "Japan struggles with soaring death toll in Suicide Forest". The Telegraph. Tokyo. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ "Sign saves lives of 29 suicidal people". Yomiuri Shimbun. February 24, 2008. Archived from the original on March 2, 2008 – via Daily Yomuri Online.

- ^ Takahashi, Yoshitomo (Summer 1988). "Aokigahara-jukai: Suicide and Amnesia in Mt. Fuji's Black Forest". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 18 (2): 164–175. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.1988.tb00150.x. PMID 3420643.

- ^ Davisson, Jack (February 25, 2021). "The Suicide Woods of Mt. Fuji". Japanzine. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2008.

- ^ Okado, Yuki (May 3, 2008). "Intruders tangle 'suicide forest' with tape". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved May 3, 2008.

- ^ "Mt. Fuji Shiozuoka Airport Basic Information". Shizuoka Prefecture. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008.

- ^ a b "[Oshirase] Heisei 21-nendo no fujisantozan shasū ni tsuite" 【お知らせ】平成21年度の富士山登山者数について [[Notice] Regarding the number of Mt. Fuji climbers in 2009] (in Japanese). Ministry of the Environment. September 17, 2009. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ "Climbing Season". Official Web Site for Mt. Fuji Climbing. Council for the Promotion of the Proper Use of Mt. Fuji. Archived from the original on December 29, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Climbing Mt. Fuji in May (closed season) [Subtitled]. YouTube. May 14, 2009. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016.

- ^ Glass, Kathy (August 26, 1990). "Climbing Mount Fuji By Night". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 20, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ a b "Mountain Trails". Official Web Site for Mt. Fuji Climbing. Council for the Promotion of the Proper Use of Mt. Fuji. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ "Climbing Mount Fuji: When to go and how to do it". Japan Rail Pass. June 15, 2022. Archived from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ "Mt. Fuji climbers to face 2,000 yen fees amid overtourism concerns". Kyodo News. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "[Yoshida Trail] 2024 Restrictions overview and FAQ". Official Web Site for Ft. Fuji Climbing. July 26, 2024. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ^ "Another Japanese prefecture to restrict night climbing on Mt. Fuji". Kyodo News. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "Mt. Fuji's selection as a cultural World Heritage site". Mt. Fuji World Heritage Div., Culture and Tourism Dept, Shizuoka Prefecture. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Melton, J. Gordon (2008). Encyclopedia of Religious Phenomena (PDF). Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 231. ISBN 9781578592593. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 17, 2023. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ "Shūzō-hin no go shōkai" 収蔵品のご紹介 [Introduction to the collection]. www.sunritz-hattori-museum.or.jp (in Japanese). Sunritz Hattori Museum of Arts. Archived from the original on March 7, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- Starr, Frederick (1924). Fujiyama, the Sacred Mountain of Japan. Chicago: Covici-McGee. OCLC 4249926. Archived from the original on March 5, 2023. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

External links

- "Fujisan (Mount Fuji)" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015.

- Fujisan (Mount Fuji) – Smithsonian Institution: Global Volcanism Program

- Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties

- Mount Fuji

- Volcanoes of Honshū

- Active volcanoes

- Izu–Bonin–Mariana Arc

- Mountains of Shizuoka Prefecture

- Mountains of Yamanashi Prefecture

- Natural monuments of Japan

- Pleistocene stratovolcanoes

- Pleistocene Asia

- Sacred mountains of Japan

- Special Places of Scenic Beauty

- Stratovolcanoes of Japan

- Subduction volcanoes

- Triple junctions

- VEI-5 volcanoes

- Tourist attractions in Shizuoka Prefecture

- Tourist attractions in Yamanashi Prefecture

- Extreme points of Japan

- World Heritage Sites in Japan

- Volcanoes of Shizuoka Prefecture

- Volcanoes of Yamanashi Prefecture

- Highest points of countries

- Internal territorial disputes of Japan